| Revision as of 20:38, 6 May 2018 view sourceCompassionate727 (talk | contribs)Edit filter helpers, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers32,143 edits Reverted good faith edits by 42.110.139.43 (talk): Unexplained content removal. (TW)Tags: Undo nowiki added← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:06, 29 December 2024 view source Ekdalian (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers9,085 edits Reverted 1 edit by Rohit Mahra (talk): Reliable and verifiable source requiredTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|South Asian ethnic group}} | |||

| {{moreref|date=January 2018}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Koch people|Koch (caste)}} | |||

| {{pp-protected|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Over-quotation|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | {{Infobox ethnic group | ||

| | group |

| group = Rajbanshi | ||

| | rawimage = Koch Rajbongshi Tribe Attire.jpg | |||

| | population = 15 million | |||

| | image_alt = | |||

| | popplace = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | caption = Rajbanshi women dancing in ], India | |||

| | langs = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | popplace = | |||

| | rels = ], ], ] | |||

| | region1 = {{Flag|India}}:<br />{{spaces|10}} ] | |||

| | related = ], ], ] | |||

| | pop1 = | |||

| | region2 = {{spaces|10}} ] | |||

| | pop2 = 3,983,316 (2011)<ref name="adibasikalyan.gov.in">{{cite web | url=https://adibasikalyan.gov.in/html/st.php | title=Tribal Development Department, Government of West Bengal }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://theprint.in/politics/matuas-rajbanshis-of-bengal-both-want-caa-so-why-did-one-vote-for-bjp-not-the-other/649171/ | title=Matuas & Rajbanshis of Bengal both want CAA. So, why did one vote for BJP & not the other? | website=] | date=4 May 2021 }}</ref><ref name="theprint.in">{{cite web | url=https://theprint.in/politics/who-are-rajbanshis-caught-in-shah-mamata-scrap-why-theyre-key-for-bjp-in-assam-bengal/639069/ | title=Who are Rajbanshis, caught in Shah-Mamata scrap & why they're key for BJP in Assam, Bengal | website=] | date=14 April 2021 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=West Bengal - Data Highlights: The Scheduled Castes -Census of India 2001|url=https://censusindia.gov.in/Tables_Published/SCST/dh_sc_westbengal.pdf|website=censusindia.gov.in|access-date=17 August 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | region3 = {{spaces|10}} ] | |||

| | pop3 = 290,079 (2023)<ref>{{Cite news |last=Verma |first=Ritesh |date=3 November 2023 |title=Bihar Caste Wise Population Share Full List: बिहार में किस जाति की कितनी संख्या, आबादी में कितना प्रतिशत हिस्सेदारी |url=https://www.livehindustan.com/bihar/story-bihar-caste-survey-counting-census-full-list-population-share-percent-obc-ebc-upper-caste-muslim-hindu-sc-st-8792660.html |work=Hindustan |language=hi |access-date=6 November 2023}}</ref> | |||

| | region4 = {{Flag|Nepal}} | |||

| | pop4 = 127,985 (2021)<ref>{{cite report |date=2021 |title=National Population and Housing Census 2021, Caste/Ethnicity Report |author=National Statistics Office |work=Government of Nepal |url=https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/results/downloads/caste-ethnicity}}</ref> | |||

| | region5 = {{Flag|Bangladesh}} | |||

| | pop5 = 13,193 (2022)<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/b343a8b4_956b_45ca_872f_4cf9b2f1a6e0/2023-09-27-09-50-a3672cdf61961a45347ab8660a3109b6.pdf|title=Table 1.4 Ethnic Population by Group and Sex|year=2021|publisher=Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics|page=33|access-date=22 November 2022|archive-date=15 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230315104610/http://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/b343a8b4_956b_45ca_872f_4cf9b2f1a6e0/2022-07-28-14-31-b21f81d1c15171f1770c661020381666.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | langs = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | religions = ] | |||

| | related_groups = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] other ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Culture of Assam}} | |||

| The '''Rajbanshi''', also '''Rajbongshi''' and '''Koch-Rajbongshi''',<ref>"In West Bengal and Bihar, they are known as "Rajbongshi and "Rajbanshi", " in Assam as "Koch," and "Koch-Rajbongshi," and in ] mainly as "Koch." {{harvcol|Roy|2018}}</ref> are peoples from ], ], eastern ], ] region of eastern ], ] of North ] and ]<ref>"The Rajbanshi as a social and cultural group are well-known to historians, sociologists and anthropologists working on northeast India. They are also familiar to those who focus on the issues surrounding minorities and indigenous groups (compare Berlie, 1982; Bessaignet, 1964; Shrestha, 2009; Wilson, 2012). A sizeable population, they are mostly concentrated in the northern parts of West Bengal and western Assam in India, in northwest Bangladesh, and the Jhapa and Morang Districts of Nepal. Although this article focuses primarily on those living in northeast India, and despite variations identified in the anthropological literature, Rajbanshi inhabiting Nepal and Bangladesh (also Bhutan and Tibet) very likely share a common historical consciousness and folklore with theirIndian kin (Das, 2009)."{{harvcol|Wilson|Bashir|2016|p=457}}</ref> who have in the past sought an association with the ].<ref name="Ramirez-14"/> Koch-Rajbanshi people speak ],<ref>An early investigation of Rajbanshi language appears in the Linguistic Survey of India, published by Grierson during the colonial period...Accordingly, Das sees no value (beyond the political) in considering Rajbanshi (or Kamtapuri/Kamata, as it is also called) as a distinct dialect.{{harvcol|Wilson|Bashir|2016|p=460}}</ref> an ], likely due to ], and in the past they might have spoken ]. The community is categorised as ] in Assam and Bihar, and ] in West Bengal.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Das |first=Ruhi Tewari, Madhuparna |date=14 April 2021 |title=Who are Rajbanshis, caught in Shah-Mamata scrap & why they're key for BJP in Assam, Bengal |url=https://theprint.in/politics/who-are-rajbanshis-caught-in-shah-mamata-scrap-why-theyre-key-for-bjp-in-assam-bengal/639069/ |work=ThePrint |access-date=6 August 2023}}</ref> In Nepal they are considered part of the Plains Janjati. In Bangladesh the community is classified as Plains ethnic group under 'Barman'. They are the largest Scheduled Caste community of West Bengal.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Chaubey |first=Santosh |title=The Significance Of Matuas and Rajbanshis in West Bengal Poll Battle, Explained |url=https://www.news18.com/news/politics/the-significance-of-matuas-and-rajbanshis-in-west-bengal-poll-battle-explained-3544697.html |work=News18 |date=17 March 2021 |access-date=6 August 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2020, ] has been created for socio-economic development and political rights of Koch-Rajbongshi community residing in Assam.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://legislative.assam.gov.in/sites/default/files/swf_utility_folder/departments/legislative_medhassu_in_oid_3/menu/document/the_kamatapur_autonomous_council_act_2020.pdf |title=The Kamatapur Autonomous Council Act 2020 |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=19 October 2020 |publisher=Legislative Department |access-date=18 July 2022 |quote=An Act to provide for the establishment of an Administrative Authority in the name and style of the Kamatapur Autonomous Council and for matters incidental therein and connected therewith}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Koch Rajbongshi people''', also known as '''Rangpuri, Rajbanshi, Koch Rajbanshi''',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.peoplegroups.org/explore/groupdetails.aspx?peid=48713|title=PEOPLE NAME: RANGPURI OF BANGLADESH|date=3 April 2018|website=PeopleGroups.org|publisher=International Mission Board, SBC.|accessdate=4 April 2018}}</ref> are an ethnic group inhabiting parts of ], northern ], and some pockets on the eastern parts of ], ], ] and northern Bangladesh. They are recognised as ] in the state of ] as Koch-Rajbongshi and ] in the state of ] as Rajbanshi. They are spread mainly in the districts of ], ], ], ] and the plain lands of ] in ]; ] and ]<nowiki/>s of Assam; and ] and ]<nowiki/>s of Bangladesh. Substantial amount of Rajbongshi population can also be found in the ] of West Bengal, ] of Bihar and the ] of Nepal. | |||

| They are related to the ethnic ] found in ] but are distinguished from them as well as from the Hindu caste called ] in ] that receives converts from different tribes.<ref>"The Koch of western Meghalaya also claim relationship with those empire-building Koch. On the other hand, Koch is known as a Hindu caste found all over the Brahmaputra Valley (Majumdar 1984: 147), and receives converts to Hinduism from different tribes (Gait 1933: 43)." {{harvcol|Kondakov|2013|p=4}}</ref> Rajbanshi (''of royal lineage'') alludes to the community's claimed connection with the ].<ref name="Ramirez-14"/> | |||

| == Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| The Rajbanshi (literal meaning: ''of the royal lineage'') community gave itself this name after 1891 following a movement to distance itself from an ethnic identity and acquire the higher social status of ] ] instead.<ref>"From 1891 a section of the Koches were trying to dissociate themselves from their original ethnic stock by describing themselves as Rajbansis or Vratya Kshatriya (Bhanga Kshatriya) their movement ended with getting Kshatriya status, being known as Rajbansis and also enlisting themselves in the list of Scheduled Caste"{{harvcol|Das|2004|p=559}}</ref><ref>"In fact, the Koches in order to assert their royal lineage used to call themselves Rajbanshis. The term, Rajbanshi was also used as an effective nomenclature to subvert the processes of hierarchical subordination of the community largely by the caste Hindus during the colonial era." {{harvcol|Roy|2014}}</ref> They tried to establish the Kshatriya identity by linking the community to the ].<ref name="Ramirez-14">"(W)hile the asserted identity of the Koch/Rabha complex seemingly shifted a great deal during the colonial period—which is therefore very confusing for observers-some converts formed an assertive ethnic group, the Koch Rajbongshi (“of royal lineage"), that claimed to be linked to the Koch dynasty."{{harv|Ramirez|2014|p=17}}</ref> The Rajbanshis were officially recorded as Koch till the 1901 census.<ref>"The Rajbansi Movement gained new momentum during 1901, because in the census the Rajbansis were not treated as distinct caste separated from the Koches and they had not been given Kshatriya status. The district magistrate denied their demand. The Rajbansis were placed with the Koches in 1901 census."{{harvcol|Das|2004|p=560}}</ref> The name ''Rajbanshi'' is a 19th century ].<ref>"But it is interesting to note that neither in the Persian records, nor in the foreign accounts, nor in any of the dynastic epigraphs of the time, the Koches are mentioned as Rajvamsis. Even the Darrang Raj Vamsavali, which is a genealogical account of the Koch royal family, and which was written in the last quarter of the 18th century, does not refer to this term. Instead all these sources call them as Koches and/or Meches."{{harv|Nath|1989|p=5}}</ref> | |||

| Etymologically, the term 'Rajbongshi'; which derives from ] of the ] sub-group; means 'of Royal Lineage' ('''''Raj'''= royal/king; '''Bongshi'''= descendant of''). The origin of such nomenclature, however, remains unclear to this day. But it is a generally accepted theory that the Rajbongshi people were ethnically and culturally related to the same ruling dynasty who ruled their land, and vice versa, i.e., the ] of northern Bengal. Many however trace this etymological relation to the dynasties prior to that of the Kochs. Contradicting views suggest that the term 'Rajbongshi' developed much later; much after the advent of the Koch dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=History of the Koch Kingdom: 1515-1615|last=Nath|first=D.|publisher=Mittal Publications|year=1989|isbn=|location=Delhi|pages=|via=}}</ref> In Assam the term 'Koch-Rajbongshi' is used, while in the case of Bengal and Nepal, they are known as Rajbongshis only. Many Rajbongshis also refer to themselves as '<nowiki/>''Shivbongshi''<nowiki/>'. | |||

| == |

== Demography == | ||

| The origins of the Rajbongshi people are shrouded in mystery. There is almost a perpetual debate about the association of the Rajbongshi people with the ]: while some claim the Rajbongshis to be ethnically the same as the Kochs, many think otherwise and claim they are distinct ethnicities. | |||

| ] of ], India]] | |||

| The local traditions claim the Rajbongshi people to be the reminiscent of a small ] group who was thought to have escaped the wrath of the legendary ] when he went on a killing spree to exterminate the Kshatriyas from the face of the Earth. Hence, the Rajbongshis were also sometimes referred to as ''Bratya'' (rejected) ''Kshatriyas, Bhanga'' (deserter/breakaway) ''Kshatriyas'' or ''Paliyas'' (one who escaped)''.'' | |||

| Worldwide, there are an estimated 11-12 million Rajbanshi people.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Balachandran |first=Vappala |date=13 February 2021 |title=The Koch-Rajbongshi Conundrum And The 2021 Elections |work=Outlook India |url=https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/opinion-the-koch-rajbongshi-conundrum-and-the-2021-elections/374122}}</ref> According to 1971 Census figures, 80% of the ] population was once of the Rajbanshi community.{{cn|date=May 2024}} As per as last late 2011 census, It has been estimated that it have came down to just mere 30%. The un-checked infiltration along the ] and intrusion of ] caused a lot of demographic change over time. Population of ], ] and Bangladeshi low-caste ] have increased rapidly in areas like ], ], ] and ] over the last 50 years, hence causing demographic changes over time.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/elections-2016/west-bengal-elections-2016/news/everyones-wooing-rajbanshis-in-north-bengal/articleshow/52101874.cms | title=Everyone's wooing Rajbanshis in North Bengal | newspaper=The Times of India | date=4 May 2016 }}</ref> In Bangladesh, the majority of Hindus in Rangpur division are from the community, although there are still some in Mymensingh division and ] of Rajshahi division. | |||

| Though the term Rajbongshi is never mentioned, there are, however, references to their present homeland in the form of ], ] and ] in various ancient texts like ], ], ], ], Bhramari tantra, and even in the great epics like the ] and the ]. References are also found in the later texts from the medieval times like the ], ], ], ] and the ]. It is from such sources that the local traditions and myths about Rajbongshi history developed. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The very first proper ethnographic details were documented by Colonial ethnographers of erstwhile ], who aimed at 'scientifically' documenting various caste and tribal groups. ] suggested that the Rajbongshis and Kochs had a common ethnic origin, though, not all Rajbongshis were Koch: | |||

| In ancient times, the land which the Rajbanshi inhabit, called '']''. Its inhabitants spoke ]. There is no mention of 'Rajbanshi' in Persian records, the ]s or the 18th-century Darrang Raja Vamsavali: the genealogical records of the ] royal family, although there is mention of the Koch as a distinct social group.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Nandi |first=Rajib |date=24 June 2014 |title=Spectacles of Ethnographic and Historical Imaginations: Kamatapur Movement and the Rajbanshi Quest to Rediscover their Past and Selves |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2014.928776 |journal=History and Anthropology |volume=25 |issue=5 |pages=571–591 |doi=10.1080/02757206.2014.928776 |s2cid=144397875 |issn=0275-7206}}</ref><ref>{{harvcol|Wilson|Bashir|2016|p=459}}</ref> From the 17th century the Koch society came under increasing brahminical influence and by the end of the 18th century a greater part of the Koch became amenable to it.<ref>"From the seventeenth century onward, however, the Koch society absorbed considerable Brahmanical content. Their claim to kshatriya status emerged as a way of reflecting and extending the new economic status of landed magnates that had arisen in the Koch society during Mughal rule. By the end of the eighteenth century this claim was filtering down the ranks of the Koch society and gaining an increasing acceptability (Ray 2002:50)."{{harvcol|Shin|2021|p=34}}</ref><ref>"So among the mass people, the process of Hinduization was slower than in the folds of the royal family"{{harvcol|Sheikh|2012|p= 252}}</ref> | |||

| ===Late 19th century and early 20th century=== | |||

| "..the highest of this tribe who in all things conform to the Hindu doctrine,...are exclusively called Rajbongsi; although I must allow, that all Rajbongsis are not Koch. Still however by far, the greater portion are of that tribe."<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Buchanan-Hamilton|first=Francis|year=1838|title=Accounts of the District of Rongpoor, 1810|journal=History, Antiquities, Topography and Statistics of Eastern India|volume= III}}</ref> | |||

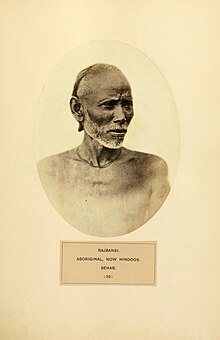

| [[File:Rajbongshi Aboriginal People.jpg|thumb| | |||

| Rajbongshi Aboriginal from Behar, {{circa|1868}}]] | |||

| Starting from 1872 to 1891, in a series of social movements,<ref>"The social movement of the Rajbanshis is a historical fact. During the Census of 1872, the Rajbanshis of Bengal and some part of Assam were trying to dissociate themselves from the tribal Koches and frantically dependent entry in the Census as a distinct caste i.e "Rajbanshi".{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=309}}</ref> a section of Koch who were at tribal or semi-tribal form in present ] and ] in an effort to promote themselves up the caste hierarchy tried to dissociate themselves from their ethnic identity by describing themselves as Rajbanshi (''of the royal lineage'').<ref>"In 1901, many Koches in North Bengal were returned as Rajbanshis. Many of the Rajbanshis have taken sacred thread and were prepared to use force in support of their claim to be returned as Kshatriya. He also writes "No part of the Census in 1891, 1901, 1911 aroused so much excitement as the return of caste which caused a great deal heart burning and in some were returned as kshatriya quarters with threats of disturbance of the peace. The Rajbanshis claimed to be included as Kshatriya, Bratya kshatriya, Barua kshatriya"{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=65}}</ref> This attempt of social upliftment was a reaction against the ill treatment and humiliation faced by the community from the caste Hindus who referred to the Koch as ] or barbarians.<ref>"The immigrants with a strong awareness to caste started interacting with indigenous Rajbanshis in differential terms. There are numerous instances of humiliation and objectionable identities of the Rajbanshis by the other caste immigrant. Few such instances of racialism interpretation and social suppression are Nagendra Nath Basu in the early twentieth century while writing his World Encyclopedia (Biswakosh) mentioned the Rajbanshis as barbarians or ''mlechha'' and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya in Bango Dar shan moots that the Koch identity."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=163}}</ref><ref>The Rajbanshis also faced humiliation and objectionable identification by the caste Hindus. Few such instances of racial misinterpretation and social suppression are: Nagendranath Basu in the early twentieth century while writing his Vishwakosh (World Encyclopedia) mentioned the Rajbanshis as barbarians or (Mlechha) and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay in Bongo Darshan moots that the Koch identity cannot be synonymous with Bengali Hindu identity. The Ranjbanshis were even denied entry into the temple of Jagannath Puri by an Act of the government in the year 1911."{{harvcol|Hazarika|2009|p=277}}</ref> The term ''Rajbanshi'' was used to connect the group with Koch royalty who called themselves ''Shiva-banshi'' or ''Rajbanshi'' under ], the founder of the Koch dynasty and a tribal who was Hinduised and promoted to Kshatriya varna in the early 1500s.<ref>"So among the mass people the process of Hinduization was slower than in the folds of the royal family. With the embracing of Hinduism, they were left with a somewhat despised name 'Koch' and adopted the name Rajbansi, a Kshatriya status which means literally 'of royal race', confined predominantly within the cultivators and the respectable classes"{{harvcol|Sheikh|2012|p=252}}</ref><ref>{{harv|Sheikh|2012|p=250}}:"But it is surmised this was nothing but Sanscritization of the ruling family which spread the Brahminical ideas among the tribes to bring them under the pale of Hinduism. The king Biswa Singha with his tribal origin embraced Hinduism and claim Kshatriya status. He is also known as Bishu succeeded in establishing his authority, styling himself as Raja, he first claimed Rajbanshi Kshatriya status"</ref><ref>"As both royal families call themselves Sivabangshi, so the mass of the Koches call themselves Rajbanshis as commented with royal families"{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|pp=63–64}}</ref> | |||

| By 1891, the Koch who came to be known as Rajbanshi claimed a new status of Bhanga Kshatriya to proof themselves to be a provincial variety of the Kshatriyas, the movement of Bhanga Kshatriya was undertaken by Harimohan Ray Khajanchi who established the "Rangpur Bratya Kshatriya Jatir Unnati Bidhayani Sabha" for the upward mobility of the community in the Hindu society.<ref>"No part of the Census in 1891, 1901, 1911 aroused so much excitement as the return of caste which caused a great deal heart burning and in some were returned as kshatriya quarters with threats of disturbance of the peace. The Rajbanshis claimed to be included as Kshatriya, Bratya kshatriya, Barua kshatriya"{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=65}}</ref> | |||

| E. T. Dalton suggested that the Rajongshis were related to the neighbouring Koch, ], ] and the ] tribes but underwent a lot of admixture to develop into a distinct community: | |||

| To justify this, the group collected reference from Hindu religious text such as the ], ] etc<ref>"The Rajbanshis also used the reference of Yoginitantra, Kalika Purana, and Bhramari Tantra to establish their claim as Bratya Kshatriya or Bhanga Kshatriya."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=309}}</ref> and created legends that they originally belonged to the ] varna but left their homeland in the fear of annihilation by the brahmin sage ] and took refuge in ] (currently in Northern bengal and Rangpur division of Bangladesh) and later came to be known as Bhanga Kshatriyas.<ref>"The Rajbanshis claimed that they were originally to the kshatriya varna and left their original homeland and took shelter in a region called Paundradesh corresponding to the districts of Rangpur, Dinajpur, Bogra, and the adjacent areas in fear of annihilation of Parasurama, a Brahman sage. In order to hide their kshatriyas identity they gave up their sacred thread and started living with the local people and gradually came to be known as the Bhanga Kshatriyas or the fallen kshatriyas."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|pp=167–168}}</ref><ref>" As both royal families call themselves Sivabangshi, so the mass of the Koches call themselves Rajbanshis as commented with royal families. Some of the Rajbanshis are now trying to prove that they are descendants of the Kshatriyas, who have taken shelter in North Bengal, being pursued by a Brahman hero Parsu Ram who extirpated the kshatriyas from the earth twenty one times. Some of them still call themselves Bhanga Kshatriyas."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|pp=63–64}}</ref> The story so created was to provide a convincing myth to assert their Kshatriya origin and perform as an ideological base for the movement<ref>"Though there are certain differences in these three accounts, the common thread that binds all of them together is the effort to create a convincing myth to provide their Kshatriya origin."{{harv|Adhikary|2009|p=168}}</ref><ref>"The claim to Kshatriya varna status through reinvention of some mythic tales provided some credibility to the ideological foundation of the Rajbanshi movement"{{harvcol|Roy|2014}}</ref> but this failed to make any wider effect on the community and were denied the Kshatriya status.<ref>{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=311}}</ref> | |||

| "The Rajbangsi are all very dark; and as their cognates, the Kacharis, Mechs, Garos, are yellow or white brown, and their northern, eastern and western neighbors are as fair or fairer, it must be from contact with the people of the south that they got their black skins.”<ref>{{Cite book|title=Descriptive Ethnology of Bengal|last=Dalton|first=E. T.|publisher=|year=1872|isbn=|location=Cacutta|pages=|via=}}</ref> | |||

| In 1910, the Rajbanshi who were classified as the member of the same caste as the Koches claimed a new identity of Rajbanshi Kshatriya, this time under the leadership of ] who established the Kshatriya Samiti in Rangpur, it separated the Rajbanshis from their Koch identity and was also successful in getting the ] status<ref>"The Kshatriya samiti also had some other objectives to fulfill. It intended first, to separate the Koch and the Rajbanshi identity emphasizing the superior status of the latter; second, to legitimize the demand to include the Rajbanshis within the Kshatriya caste; third, to inculcate brahmanical values and practices among the Rajbanshis"{{harvcol|Hazarika|2009|p=277}}</ref> after getting recognition from different Brahmin pandits of ], ], ] and ].{{sfn|Das|2004|p=560}} Following this, the district magistrate gave permission to use surnames like ], ], ], ], ] etc. to replace the older traditional surnames like ], ], ] or ]{{sfn|Adhikary|2009|pp=169–170}} and the Kshatriya status was granted in the final report of 1911 census.{{sfn|Das|2004|p=560}} The movement manifested itself in sankritising tendencies with an assertion of '']'' origin and striving for higher social status by imitating ] customs and rituals.{{sfn|Das|2004|p=561}} | |||

| Beverly claimed that the Rajbongshis, Paliyas and the Kochs had a common origin but also states that Rajbongshi is not a term exclusive to Northern Bengal: | |||

| With this ]s of Rajbanshi took ritual bath in the ] and adopted the practices of the ], like the wearing of the sacred thread (]), adoption of ] name, shortening in period of 'asauch' from 30 days to 12.<ref>"At the initial stage, the Rajbanshis caste leaders typically attempted to improve their social standing by altering their customs to resemble the ways of life of 'twice- born'. As a formal work of 'twice born' they started wearing sacred thread and adopted gotra (clan) name. They also reduced the period of mourning and ritual pollution (as ouch) from thirty to twelve days to corresponding with that of the kshatriya."{{harv|Adhikary|2009|p=169}}</ref><ref>" In order to gratify their ritual rank aspiration they began to imitate the values, practices and cultural styles of ‘twice born’ castes that formed a part of Hindu Great tradition. Since 1912, a number of mass thread wearing ceremonies (Milan Kshetra) were organized in different districts by the ‘Kshatriya Samiti’ where lakhs of Rajbanshi's donned the sacred thread as a mark of Kshatriya status."{{harvcol|Hazarika|2009|p=277}}</ref> They gave up practices that were forbidden in the Hindu religion like the drinking of liquor (]) and rearing of pigs.{{sfn|Adhikary|2009|p=170}} From 1872 to 1911 in an effort to be a part of the higher caste, the Koch went through three distinct social identities in the census, Koch to Rajbanshi (1872), Rajbanshi to Bhanga Kshatriya (1891), Bhanga Kshatriya to Rajbanshi Kshatriya (1911).<ref>"In their desire to be recorded as a member of high caste, they passed through at least four distinct social identities from one census to another i.e. from Koch to Rajbanshi (1872 A.D.), from Rajbanshi to Bratya/ Bhanga Kshatriya(1891), from Bratya/Bhanga Kshatriya· to Rajbanshi Kshatriya (1901,1911,1921 A.D.) and from Rajbanshi Kshatriya to only Kshatriya."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=312}}</ref> | |||

| "The Koch, Paliya and Rajbansi are for the most partone and the same tribe…Rajbansi is an indefinite term and some few individuals entered under it may possibly belong to other castes. In lower delta, for instance, Rajbansis are said to be a sub-division of Tiyars; but by far the great majority of those returned as such, coming as they do from districts of Dinajepore, Rungpore and Julpigoree, are clearly the same as Koch and Paliyas who are found in those districts.”<ref>Beverly, H., | |||

| Today the Koch-Rajbongshis are found throughout North Bengal, particularly in the ], as well as parts of ], northern Bangladesh (]), the ] of ] and Bihar, and Bhutan.<ref>"Today, the Koch Rajbanshi people are located in North Bengal, Assam (with a major concentration in west Assam), Garo hills of Meghalaya, Purnia, Kishanganj, and Katihar districts of Bihar, Jhapa and Biratnagar districts of Nepal, Rangpur, East Dinajpur districts and some parts of northwest Mymensingh, northern Rajshahi and Bogra districts of Bangladesh and lower parts of Bhutan (Nalini Ranjan Ray 2009)." {{harvcol|Roy|2014}}</ref> | |||

| ''Report on the Census of Bengal, Calcutta, 1872.'' | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Some writers suggest that the Rajbanshi people constitute from different ethnic groups<ref name="roy">{{harvp|Roy|2014}}:"Suniti Kumar Chatterji observed that Rajbanshis were Koch in origin and belonged to the larger Bodo group. They were Hinduised or semi-Hinduised and had discarded their Tibeto-Burman language, adopting northern Bengali sub-language as their tongue."</ref><ref>{{harvp|Das|Mukherjee|Bhattacharjee|1967|p=433}}: "And the various ethnological reports concur on the origin of the Rajbanshi from the Koch, the Mech and the Paliya tribes"</ref><ref>"The large tract of country called Mechpara in the Gowalparah District no doubt took its name from them, and the proprietor is a Mech; but he and most of his people repudiate this origin and call themselves Rajbangsis"{{harvcol|Mitra|1953|p=224}}</ref> who underwent ] to reach the present form and in the process abandoned their original ] tongue to be replaced by the ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Debnath|first1=Monojit|last2=Palanichamy|first2=Malliya G.|last3=Mitra|first3=Bikash|last4=Jin|first4=Jie-Qiong|last5=Chaudhuri|first5=Tapas K.|last6=Zhang|first6=Ya-Ping|date=2011|title=Y-chromosome haplogroup diversity in the sub-Himalayan Terai and Duars populations of East India|journal=Journal of Human Genetics|language=en|volume=56|issue=11|pages=765–771|doi=10.1038/jhg.2011.98|pmid=21900945|s2cid=2735604|issn=1435-232X|doi-access=free}}</ref> There exist Rajbanshi people in ] districts of ], ], ] and ] who might not belong to the same ethnic stock.<ref>"On the other hand, there are Rajbanshi in Midnapur, 24 Paraganas, Hoogly and Nadia district who may not be of the same stock and do not speak this language"{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=138}}</ref><ref>"Thompson states, "The Rajbanshis are the indigenous people of Northern Bengal and the third Largest Hindu Caste in the province. Their total number has been exaggerated by the fact that a member of fisherman caste in Mymensingh, Nadia and Murshidabad returned themselves as Rajbanshis."{{harvcol|Adhikary|2009|p=65}}</ref> | |||

| == lifestyle and Culture == | |||

| The Rajbongshi community had traditionally been a largely agricultural community, cultivating mainly rice, pulses and maize. Rice is the staple food for the majority of the population. Even in the 21st century, a large portion of this community still adhere to a rural lifestyle, though urbanization is on constant rise. The food consumed and the diet pattern is not very different from those in other parts of Bengal. Rice and Pulses are consumed on regular basis along with vegetables and ''bhajis'' (fries- mainly potatoes). Typical is the ''Dhékir sāg'' and ''naphā sāg,'' two types of vegetable preparation, mostly boiled with very little added oil, out of newly-born shoots of fern leaves. In lower Assam, a vegetable preparation of bamboo shoots is also consumed. Consumption of stale rice or ''pantha bhāt'' is common within Rajbongshi community. Cooking is mainly done using mustard oil, though sunflower oil is sometimes used. As far as non-vegetarian foods are concerned, the Rajbongshi population consumes a large amount of meat and eggs unlike other neighborhood populations from Bengal region, who consume large amount of fish. Goat meat and sheep (if available) is generally consumed, and consumption of fowl meat is discouraged, especially by the older generations, though such barriers now cease to exist. Eggs of Ducks and poultry are consumed. Fish is also consumed but not in very large number. The rivers of northern Bengal does not sustain large varieties of fishes because of its non-perennial nature. However, in lower Assam areas, large rivers like the ] sustain large varieties of fish which becomes an important part of the dietary habit of the Rajbongshis living there. | |||

| In 1937, various members of the Rajbanshi Kshatriya Samiti were elected to the Bengal Legislative Council from ], ], ], and ]. These MLAs helped form the Independent Scheduled Caste Party. ] became a minister-in-charge of forests and excise in the ] government. However, the reservations provided to them also increased conflict within organisations representing Scheduled Castes, and many leaders of the Kshatriya Samiti left for the Congress party, while much of the masses were drawn to the Communists. In 1946, several Rajbanshi candidates were elected on reserved seats from North Bengal, with only one Rajbanshi candidate from the Kshatriya Samiti and Communist Party being elected. This division of Rajbanshi leadership meant they were in little position to have a say in the ], although Namasudra Community leader ] attempted to organise lower castes against Partition. | |||

| A typical Rajbongshi home is essentially of rectangular pattern, with an open space (aṅgina) in the middle. This is done mostly for protection against both wild animals and strong winds. The north side holds the betel nut and fruit gardens, the west contains Bamboo gardens while the east and the south is generally left open to allow sunshine and air penetrate into the household. Rajbongshi dress pattern derives largely from the surrounding geographic and cultural environment. The traditional clothing for men is ''dhoti and'' shirt or inners, while for women is bukuni-patani; a piece of cloth tied around the chest that extends up to the knee.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Rajbansis of North Bengal|last=Sanyal|first=Charu Chandra|publisher=The Asiatic Society|year=1965|isbn=|location=Kolkata|pages=|via=}}</ref> However, nowadays shirts and trousers have become common for men, while women largely follows the modern Bengali style of wearing a sari. Salwar Kameez is also popular among the younger generations. | |||

| === Post-independence (1947–present) === | |||

| Music forms an integral part of Rajbongshi culture. The main musical forms of Rajongshi culture are ] and Chatka and pala gaan. Various instruments are used for such performances like, string instruments like-dotora, sarindra and bena;double membrane instruments like- tasi, dhak, khol and mridanga; gongs and bells like-kansi, kartal; and wind instruments like- sanai and kupa bansi.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Rajbansis of North Bengal|last=Sanyal|first=Charu Chandra|publisher=The Asiatic Society|year=1965|isbn=|location=Calcutta|pages=|via=}}</ref> | |||

| After Partition, the Kshatriya Samithi lost its headquarters at Rangpur and attempted to reestablish itself at ]. However, a variety of new organisations to represent the Rajbanshi were being created. In Assam, the Rajbanshis were classified in a special category of ] called MOBC. In North Bengal, the various new Rajbanshi organisations began to see the Rajbanshi identity as ethnolinguistic in nature rather than a caste, since the various other communities living in North Bengal and Lower Assam also spoke the Rajbanshi language. This linguistic awareness was heightened in 1953, when the government decided to reorganise the states on linguistic basis. Many of these organisations, such as Siliguri Zonal Rajbanshi Kshatriya Samiti agitated for the merger of ] of Bihar and ] of Assam into West Bengal since these regions were largely populated by Rajbanshi speakers. This was continued into the 1960s with Rajbanshi activists frequently demanding for their speech to be recognised as separate from Bengali.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Barman |first=Rup Kumar |date=2015 |title=Culture of Difference in Ethnic Identity: A new Look on the transition of Caste identity into Cultural identity of the Rajbanshis of Northern Bengal and Lower Assam |url=https://www.cinnamaracollege.org/Publication/pdf/The%20Mirror,%20Vol-II,%202015(PDF).PDF#page=56 |journal=The Mirror |volume=2 |pages=56–69}}</ref> | |||

| == |

== Occupation == | ||

| The Rajbongshis were traditionally agriculturalists, but due to their numerical dominance in North Bengal there were significant occupational differences among them. Most were agricultural labourers (''halua'') or sharecroppers (''adhiar''). These often worked for landed cultivators, called ''dar-chukanidars''. Above them were the ''chukandiars'', who could sub-let their land to ''dar-chukanidars'', and ''jotedars'', who acted as intermediaries between the ''chukandiars'' and the ''zamindars'', landowners that got their land from the government in exchange for a fixed amount of revenue. Some Rajbongshis were ''zamindars'' or ''jotedars''.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Barman|first=Rup Kumar|title=A new Look on the transition of Caste identity into Cultural identity of the Rajbanshis of Northern Bengal and Lower Assam|url=https://www.cinnamaracollege.org/Publication/pdf/The%20Mirror,%20Vol-II,%202015(PDF).PDF#page=56|journal=The Mirror|pages=56–70}}</ref> | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == Lifestyle and culture == | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| According to a 2019 research, the Koch Rajbongshi community has an oral tradition of agriculture, dance, music, medical practices, song, the building of house, culture, and language. Ideally the tribe transfer the know-how from one generation to another.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Singha |first1=Surjit |last2=Singha |first2=Ranjit |title=Sustainable Entrepreneurship in North East India |date=2019 |publisher=Tsenov Academic Publishing House |location=Bulgaria |isbn=9789542317524 |pages=161–187 |edition=1 |url=https://www.academia.edu/40917399 |access-date=14 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| * | |||

| Music forms are integral part of Koch-Rajbongshi culture. The main musical forms of Koch-Rajbongshi culture are ], Chatka, Chorchunni, Palatia, Lahankari, Tukkhya, Bishohora Pala among many others. Various instruments are used for such performances, string instruments like Dotora, Sarindra and Bena, double-membrane instruments like Tasi, Dhak, Khol, Desi Dhol and Mridanga, gongs and bells like Kansi, Khartal and wind instruments like Sanai, Mukha bansi and Kupa bansi.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Rajbansis of North Bengal|last=Sanyal|first=Charu Chandra|publisher=The Asiatic Society|year=1965|location=Calcutta}}</ref> | |||

| ==Rajbanshi people in Nepal== | |||

| The ] classifies the Rajbanshi people within the broader social group of Terai Janajati.<ref></ref> At the time of the Nepal census of 2011, 115,242 people (0.4% of the population of Nepal) were Rajbanshi. The frequency of Rajbanshi people by province was as follows: | |||

| * ] (2.5%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| * ] (0.0%) | |||

| The frequency of Rajbanshi people was higher than national average (0.4%) in the following districts:<ref></ref> | |||

| * ] (9.1%) | |||

| * ] (3.9%) | |||

| ==Notable people== | |||

| <!--Arrange alphabetically by LAST NAME--> | |||

| <!--Include only when the subject(s) has an article in this English Misplaced Pages--> | |||

| * ], Indian social reformer of the Rajbanshi community from West Bengal | |||

| * ], Indian ] and gold medal winner at ] from West Bengal | |||

| * ], Indian politician from West Bengal | |||

| * ], Nepalese cricketer of ] | |||

| * ], Indian Politician from Assam | |||

| * ], Nepalese politician associated with ] | |||

| * ], Indian actress from West Bengal | |||

| * ], Former Chief Minister of ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| *{{Cite journal |last=Nandi |first=Rajib |date=24 June 2014 |title=Spectacles of Ethnographic and Historical Imaginations: Kamatapur Movement and the Rajbanshi Quest to Rediscover their Past and Selves |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2014.928776 |journal=History and Anthropology |volume=25 |issue=5 |pages=571–591 |doi=10.1080/02757206.2014.928776 |s2cid=144397875 |issn=0275-7206}} | |||

| * {{cite thesis |type=PhD |last=Adhikary |first=Madhab Chandra |title=Ethno Cultural Identity Crisis of the Rajbanshis of North Eastern Part of india and Nepal and Bangladesh during the period of 1891 to 1979 |publisher=University of North Bengal |year=2009 |hdl=10603/137486}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Adhikary |first=Madhab Chandra |year=2010 |title=Socio-political movement in post colonial North Bengal: A case study of the Rajbanshis |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=71 |pages=1233–1242 |jstor=44147592 |issn=2249-1937}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.32096 |title=Kirata-Jana-Krti |last=Chatterji |first=S.K |publisher=The Asiatic Society |year=1951 |location=Calcutta}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Das |first=Jitendra Nath |title=The backwardness of the Rajbansis and the Rajbansi kshatriya movement (1891-1936) |year=2004 |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=65 |pages=559–563 |jstor=44144770 |issn=2249-1937}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Das |first1=S. R. |last2=Mukherjee |first2=D. P. |last3=Bhattacharjee |first3=P. N. |title=Survey of the Blood Groups and PTC Taste Among the Rajbanshi Caste of West Bengal (ABO, MNS, Rh, Duffy and Diego) |year=1967 |journal=Acta Genetica et Statistica Medica |volume=17 |issue=5 |pages=433–445 |doi=10.1159/000152094 |jstor=45103942 |pmid=6072621}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Gogoi |first=Jahnavi |title=Agrarian System of Medieval Assam |publisher=Concept Publishing Company |place=New Delhi |year=2002}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Hazarika |first=S. |year=2009 |title=Unrest and Displacement: Rajbanshis in North Bengal |editor-last=Basu |editor-first=S |journal=The Fleeing People of South Asia: Selections from Refugee Watch |pages=274–282 |publisher=Anthem Press |doi=10.7135/UPO9781843317784.037 |isbn=9781843317784}} | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Jacquesson |first=François |title=Discovering Boro-Garo: History of an analytical and descriptive linguistic category |journal=European Bulletin of Himalayan Research |volume=32 |year=2008 |pages=14–49}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Kondakov |first=Alexander |editor1-first=Gwendolyn |editor1-last=Hyslop |editor2-first=Stephen |editor2-last=Morey |editor3-first=Mark W |editor3-last=Post |year=2013 |title=Koch dialects of Meghalaya and Assam: A sociolinguistic survey |journal=North East Indian Linguistics |volume=5 |pages=3–59 |publisher=Cambridge University Press India |doi=10.1017/9789382993285.003 |isbn=9789382993285}} | |||

| * {{cite book |url= |last=Mitra |first=A |title=The Tribes and Castes of West Bengal |publisher=West Bengal Government Press |location=Alipore, West bengal |year=1953}} | |||

| * {{Citation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ECxUOSudNGYC |last=Nath |first=D. |title=History of the Koch Kingdom, C. 1515-1615 |pages=5–6 |publisher=Mittal Publications |year=1989 |isbn=8170991099}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ramirez |first=Philippe |url=https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01446144/document |title=People of the Margins - Across Ethnic Boundaries in North-East India |date=2014 |language=en}} | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Roy |first=Hirokjeet |title=Politics of Janajatikaran: Koch Rajbanshis of Assam |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |volume=49 |issue=47 |year=2014 |url=https://www.epw.in/journal/2014/47/reports-states-web-exclusives/politics-janajatikaran.html}} | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Roy |first=Kapil Chandra |title=Demand for Scheduled Tribe Status by Koch-Rajbongshis |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |volume=53 |issue=44 |year=2018 |url=https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/44/commentary/demand-scheduled-tribe-status-koch.html}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Sheikh |first=Amiruzzaman |title=The 16th century Koch kingdom: Evolving patterns of sankritization |year=2012 |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=73 |pages=249–254 |jstor=44156212 |issn=2249-1937}} | |||

| *{{cite journal|last=Shin|first=Jae-Eun|title=Sword and Words: A Conflict Between Kings and Brahmins in the Bengal Frontier, Kāmatāpur 15th-16th Centuries|journal=Journal of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums|year=2021|publisher=Government of West Bengal|volume=3|pages=21–36}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Wilson |first1=Margot |last2=Bashir |first2=Kamran |date=16 March 2016 |title='King's inheritors': understanding the ethnic discourse on the Rajbanshi as an indigenous community |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2016.1148594 |journal=Social Identities |volume=22 |issue=5 |pages=455–470 |doi=10.1080/13504630.2016.1148594 |s2cid=146814921 |issn=1350-4630}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Roy |first=Gautam chandra |date=9 July 2022 |title=Dynamics of Being Rajbanshi |others= Tribe to Caste and the Process of ‘Retribalisation’ |url=https://www.epw.in/journal/2022/28/commentary/dynamics-being-rajbanshi.html |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |language=en |volume=57 |issue=28 |url-access=subscription}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| {{West Bengal}} | |||

| {{Assam}} | |||

| {{Ethnic groups in Nepal}} | {{Ethnic groups in Nepal}} | ||

| {{Ethnic groups in Bangladesh}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:06, 29 December 2024

South Asian ethnic group Not to be confused with Koch people or Koch (caste).

| This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. Please help summarize the quotations. Consider transferring direct quotations to Wikiquote or excerpts to Wikisource. (May 2024) |

Ethnic group

Rajbanshi women dancing in Assam, India Rajbanshi women dancing in Assam, India | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| West Bengal | 3,983,316 (2011) |

| Bihar | 290,079 (2023) |

| 127,985 (2021) | |

| 13,193 (2022) | |

| Languages | |

| Rajbanshi, Assamese, Bengali, Nepali | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nashya Shaikh, Koch, Rabhas, Garos, Boros, Mech, Tharu other Indo-Aryan people | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Assam |

|---|

|

| HistoryProto-historic Classical Medieval Modern |

| PeopleAssamese peoples Scheduled tribes |

| LanguagesMajor Minor Extinct |

| Traditions |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

ReligionMajor

|

| Art |

| LiteratureHistory Archives Genres Institutions Awards |

| Music and performing arts |

Media

|

| Monuments |

Symbols

|

| Organisations |

The Rajbanshi, also Rajbongshi and Koch-Rajbongshi, are peoples from Lower Assam, North Bengal, eastern Bihar, Terai region of eastern Nepal, Rangpur division of North Bangladesh and Bhutan who have in the past sought an association with the Koch dynasty. Koch-Rajbanshi people speak Kamatapuri, an Indo-Aryan language, likely due to language shift, and in the past they might have spoken Tibeto-Burman languages. The community is categorised as OBC in Assam and Bihar, and SC in West Bengal. In Nepal they are considered part of the Plains Janjati. In Bangladesh the community is classified as Plains ethnic group under 'Barman'. They are the largest Scheduled Caste community of West Bengal.

In 2020, Kamatapur Autonomous Council has been created for socio-economic development and political rights of Koch-Rajbongshi community residing in Assam.

They are related to the ethnic Koch people found in Meghalaya but are distinguished from them as well as from the Hindu caste called Koch in Upper Assam that receives converts from different tribes. Rajbanshi (of royal lineage) alludes to the community's claimed connection with the Koch dynasty.

Etymology

The Rajbanshi (literal meaning: of the royal lineage) community gave itself this name after 1891 following a movement to distance itself from an ethnic identity and acquire the higher social status of Kshatriya Hindu varna instead. They tried to establish the Kshatriya identity by linking the community to the Koch dynasty. The Rajbanshis were officially recorded as Koch till the 1901 census. The name Rajbanshi is a 19th century neologism.

Demography

Worldwide, there are an estimated 11-12 million Rajbanshi people. According to 1971 Census figures, 80% of the North Bengal population was once of the Rajbanshi community. As per as last late 2011 census, It has been estimated that it have came down to just mere 30%. The un-checked infiltration along the Indo-Bangladesh border and intrusion of Biharis caused a lot of demographic change over time. Population of Bengali Muslims, Bihari Muslims and Bangladeshi low-caste Namasudras have increased rapidly in areas like Jalpaiguri, Oodlabari, Gairkata and Jaigaon over the last 50 years, hence causing demographic changes over time. In Bangladesh, the majority of Hindus in Rangpur division are from the community, although there are still some in Mymensingh division and Bogra district of Rajshahi division.

History

In ancient times, the land which the Rajbanshi inhabit, called Kamarupa. Its inhabitants spoke Tibeto-Burman languages. There is no mention of 'Rajbanshi' in Persian records, the Ahom Buranjis or the 18th-century Darrang Raja Vamsavali: the genealogical records of the Koch Bihar royal family, although there is mention of the Koch as a distinct social group. From the 17th century the Koch society came under increasing brahminical influence and by the end of the 18th century a greater part of the Koch became amenable to it.

Late 19th century and early 20th century

Starting from 1872 to 1891, in a series of social movements, a section of Koch who were at tribal or semi-tribal form in present North Bengal and Western Assam in an effort to promote themselves up the caste hierarchy tried to dissociate themselves from their ethnic identity by describing themselves as Rajbanshi (of the royal lineage). This attempt of social upliftment was a reaction against the ill treatment and humiliation faced by the community from the caste Hindus who referred to the Koch as mleccha or barbarians. The term Rajbanshi was used to connect the group with Koch royalty who called themselves Shiva-banshi or Rajbanshi under Biswa Singha, the founder of the Koch dynasty and a tribal who was Hinduised and promoted to Kshatriya varna in the early 1500s.

By 1891, the Koch who came to be known as Rajbanshi claimed a new status of Bhanga Kshatriya to proof themselves to be a provincial variety of the Kshatriyas, the movement of Bhanga Kshatriya was undertaken by Harimohan Ray Khajanchi who established the "Rangpur Bratya Kshatriya Jatir Unnati Bidhayani Sabha" for the upward mobility of the community in the Hindu society.

To justify this, the group collected reference from Hindu religious text such as the Kalika Purana, Yogini Tantra etc and created legends that they originally belonged to the kshatriya varna but left their homeland in the fear of annihilation by the brahmin sage Parashurama and took refuge in Paundradesh (currently in Northern bengal and Rangpur division of Bangladesh) and later came to be known as Bhanga Kshatriyas. The story so created was to provide a convincing myth to assert their Kshatriya origin and perform as an ideological base for the movement but this failed to make any wider effect on the community and were denied the Kshatriya status.

In 1910, the Rajbanshi who were classified as the member of the same caste as the Koches claimed a new identity of Rajbanshi Kshatriya, this time under the leadership of Panchanan Barma who established the Kshatriya Samiti in Rangpur, it separated the Rajbanshis from their Koch identity and was also successful in getting the Kshatriya status after getting recognition from different Brahmin pandits of Mithila, Rangpur, Kamrup and Koch Bihar. Following this, the district magistrate gave permission to use surnames like Roy, Ray, Barman, Sinha, Adhikary etc. to replace the older traditional surnames like Sarkar, Ghosh, Das or Mandal and the Kshatriya status was granted in the final report of 1911 census. The movement manifested itself in sankritising tendencies with an assertion of Aryan origin and striving for higher social status by imitating higher caste customs and rituals.

With this lakhs of Rajbanshi took ritual bath in the Karatoya river and adopted the practices of the twice born (Dvija), like the wearing of the sacred thread (Upanayana), adoption of gotra name, shortening in period of 'asauch' from 30 days to 12. They gave up practices that were forbidden in the Hindu religion like the drinking of liquor (Teetotalism) and rearing of pigs. From 1872 to 1911 in an effort to be a part of the higher caste, the Koch went through three distinct social identities in the census, Koch to Rajbanshi (1872), Rajbanshi to Bhanga Kshatriya (1891), Bhanga Kshatriya to Rajbanshi Kshatriya (1911).

Today the Koch-Rajbongshis are found throughout North Bengal, particularly in the Dooars, as well as parts of Lower Assam, northern Bangladesh (Rangpur Division), the Terai of eastern Nepal and Bihar, and Bhutan.

Some writers suggest that the Rajbanshi people constitute from different ethnic groups who underwent Sankritisation to reach the present form and in the process abandoned their original Tibeto-burman tongue to be replaced by the Indo-Aryan languages. There exist Rajbanshi people in South Bengal districts of Midnapur, 24 Paraganas, Hoogly and Nadia who might not belong to the same ethnic stock.

In 1937, various members of the Rajbanshi Kshatriya Samiti were elected to the Bengal Legislative Council from Rangpur, Dinajpur, Malda, and Jalpaiguri. These MLAs helped form the Independent Scheduled Caste Party. Upendra Nath Barman became a minister-in-charge of forests and excise in the Fazlul Haq government. However, the reservations provided to them also increased conflict within organisations representing Scheduled Castes, and many leaders of the Kshatriya Samiti left for the Congress party, while much of the masses were drawn to the Communists. In 1946, several Rajbanshi candidates were elected on reserved seats from North Bengal, with only one Rajbanshi candidate from the Kshatriya Samiti and Communist Party being elected. This division of Rajbanshi leadership meant they were in little position to have a say in the Partition of Bengal, although Namasudra Community leader Jogendra Nath Mandal attempted to organise lower castes against Partition.

Post-independence (1947–present)

After Partition, the Kshatriya Samithi lost its headquarters at Rangpur and attempted to reestablish itself at Dinhata. However, a variety of new organisations to represent the Rajbanshi were being created. In Assam, the Rajbanshis were classified in a special category of OBC called MOBC. In North Bengal, the various new Rajbanshi organisations began to see the Rajbanshi identity as ethnolinguistic in nature rather than a caste, since the various other communities living in North Bengal and Lower Assam also spoke the Rajbanshi language. This linguistic awareness was heightened in 1953, when the government decided to reorganise the states on linguistic basis. Many of these organisations, such as Siliguri Zonal Rajbanshi Kshatriya Samiti agitated for the merger of Purnia division of Bihar and Goalpara district of Assam into West Bengal since these regions were largely populated by Rajbanshi speakers. This was continued into the 1960s with Rajbanshi activists frequently demanding for their speech to be recognised as separate from Bengali.

Occupation

The Rajbongshis were traditionally agriculturalists, but due to their numerical dominance in North Bengal there were significant occupational differences among them. Most were agricultural labourers (halua) or sharecroppers (adhiar). These often worked for landed cultivators, called dar-chukanidars. Above them were the chukandiars, who could sub-let their land to dar-chukanidars, and jotedars, who acted as intermediaries between the chukandiars and the zamindars, landowners that got their land from the government in exchange for a fixed amount of revenue. Some Rajbongshis were zamindars or jotedars.

Lifestyle and culture

According to a 2019 research, the Koch Rajbongshi community has an oral tradition of agriculture, dance, music, medical practices, song, the building of house, culture, and language. Ideally the tribe transfer the know-how from one generation to another.

Music forms are integral part of Koch-Rajbongshi culture. The main musical forms of Koch-Rajbongshi culture are Bhawaiyya, Chatka, Chorchunni, Palatia, Lahankari, Tukkhya, Bishohora Pala among many others. Various instruments are used for such performances, string instruments like Dotora, Sarindra and Bena, double-membrane instruments like Tasi, Dhak, Khol, Desi Dhol and Mridanga, gongs and bells like Kansi, Khartal and wind instruments like Sanai, Mukha bansi and Kupa bansi.

Rajbanshi people in Nepal

The 2011 Nepal census classifies the Rajbanshi people within the broader social group of Terai Janajati. At the time of the Nepal census of 2011, 115,242 people (0.4% of the population of Nepal) were Rajbanshi. The frequency of Rajbanshi people by province was as follows:

- Koshi Province (2.5%)

- Bagmati Province (0.0%)

- Gandaki Province (0.0%)

- Lumbini Province (0.0%)

- Madhesh Province (0.0%)

- Sudurpashchim Province (0.0%)

- Karnali Province (0.0%)

The frequency of Rajbanshi people was higher than national average (0.4%) in the following districts:

Notable people

- Panchanan Barma, Indian social reformer of the Rajbanshi community from West Bengal

- Swapna Barman, Indian heptathlete and gold medal winner at 2018 Asian Games from West Bengal

- Upendranath Barman, Indian politician from West Bengal

- Lalit Rajbanshi, Nepalese cricketer of Nepal National Cricket Team

- Madhab Rajbangshi, Indian Politician from Assam

- Tuluram Rajbanshi, Nepalese politician associated with Nepal Communist Party

- Mouni Roy, Indian actress from West Bengal

- Sarat Chandra Singha, Former Chief Minister of Assam

See also

Notes

- "Tribal Development Department, Government of West Bengal".

- "Matuas & Rajbanshis of Bengal both want CAA. So, why did one vote for BJP & not the other?". ThePrint. 4 May 2021.

- "Who are Rajbanshis, caught in Shah-Mamata scrap & why they're key for BJP in Assam, Bengal". ThePrint. 14 April 2021.

- "West Bengal - Data Highlights: The Scheduled Castes -Census of India 2001" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Verma, Ritesh (3 November 2023). "Bihar Caste Wise Population Share Full List: बिहार में किस जाति की कितनी संख्या, आबादी में कितना प्रतिशत हिस्सेदारी". Hindustan (in Hindi). Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- National Statistics Office (2021). National Population and Housing Census 2021, Caste/Ethnicity Report. Government of Nepal (Report).

- "Table 1.4 Ethnic Population by Group and Sex" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 2021. p. 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "639 Identifier Documentation: aho – ISO 639-3". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). SIL International. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

Ahom

- "Population by Religious Communities". Census India – 2001. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Census Data Finder/C Series/Population by Religious Communities

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

2011census/C-01/DDW00C-01 MDDS.XLS

- "In West Bengal and Bihar, they are known as "Rajbongshi and "Rajbanshi", " in Assam as "Koch," and "Koch-Rajbongshi," and in Meghalaya mainly as "Koch." (Roy 2018)

- "The Rajbanshi as a social and cultural group are well-known to historians, sociologists and anthropologists working on northeast India. They are also familiar to those who focus on the issues surrounding minorities and indigenous groups (compare Berlie, 1982; Bessaignet, 1964; Shrestha, 2009; Wilson, 2012). A sizeable population, they are mostly concentrated in the northern parts of West Bengal and western Assam in India, in northwest Bangladesh, and the Jhapa and Morang Districts of Nepal. Although this article focuses primarily on those living in northeast India, and despite variations identified in the anthropological literature, Rajbanshi inhabiting Nepal and Bangladesh (also Bhutan and Tibet) very likely share a common historical consciousness and folklore with theirIndian kin (Das, 2009)."(Wilson & Bashir 2016:457)

- ^ "(W)hile the asserted identity of the Koch/Rabha complex seemingly shifted a great deal during the colonial period—which is therefore very confusing for observers-some converts formed an assertive ethnic group, the Koch Rajbongshi (“of royal lineage"), that claimed to be linked to the Koch dynasty."(Ramirez 2014, p. 17)

- An early investigation of Rajbanshi language appears in the Linguistic Survey of India, published by Grierson during the colonial period...Accordingly, Das sees no value (beyond the political) in considering Rajbanshi (or Kamtapuri/Kamata, as it is also called) as a distinct dialect.(Wilson & Bashir 2016:460)

- Das, Ruhi Tewari, Madhuparna (14 April 2021). "Who are Rajbanshis, caught in Shah-Mamata scrap & why they're key for BJP in Assam, Bengal". ThePrint. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chaubey, Santosh (17 March 2021). "The Significance Of Matuas and Rajbanshis in West Bengal Poll Battle, Explained". News18. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- "The Kamatapur Autonomous Council Act 2020" (PDF). Legislative Department. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

An Act to provide for the establishment of an Administrative Authority in the name and style of the Kamatapur Autonomous Council and for matters incidental therein and connected therewith

- "The Koch of western Meghalaya also claim relationship with those empire-building Koch. On the other hand, Koch is known as a Hindu caste found all over the Brahmaputra Valley (Majumdar 1984: 147), and receives converts to Hinduism from different tribes (Gait 1933: 43)." (Kondakov 2013:4)

- "From 1891 a section of the Koches were trying to dissociate themselves from their original ethnic stock by describing themselves as Rajbansis or Vratya Kshatriya (Bhanga Kshatriya) their movement ended with getting Kshatriya status, being known as Rajbansis and also enlisting themselves in the list of Scheduled Caste"(Das 2004:559)

- "In fact, the Koches in order to assert their royal lineage used to call themselves Rajbanshis. The term, Rajbanshi was also used as an effective nomenclature to subvert the processes of hierarchical subordination of the community largely by the caste Hindus during the colonial era." (Roy 2014)

- "The Rajbansi Movement gained new momentum during 1901, because in the census the Rajbansis were not treated as distinct caste separated from the Koches and they had not been given Kshatriya status. The district magistrate denied their demand. The Rajbansis were placed with the Koches in 1901 census."(Das 2004:560)

- "But it is interesting to note that neither in the Persian records, nor in the foreign accounts, nor in any of the dynastic epigraphs of the time, the Koches are mentioned as Rajvamsis. Even the Darrang Raj Vamsavali, which is a genealogical account of the Koch royal family, and which was written in the last quarter of the 18th century, does not refer to this term. Instead all these sources call them as Koches and/or Meches."(Nath 1989, p. 5)

- Balachandran, Vappala (13 February 2021). "The Koch-Rajbongshi Conundrum And The 2021 Elections". Outlook India.

- "Everyone's wooing Rajbanshis in North Bengal". The Times of India. 4 May 2016.

- Nandi, Rajib (24 June 2014). "Spectacles of Ethnographic and Historical Imaginations: Kamatapur Movement and the Rajbanshi Quest to Rediscover their Past and Selves". History and Anthropology. 25 (5): 571–591. doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.928776. ISSN 0275-7206. S2CID 144397875.

- (Wilson & Bashir 2016:459)

- "From the seventeenth century onward, however, the Koch society absorbed considerable Brahmanical content. Their claim to kshatriya status emerged as a way of reflecting and extending the new economic status of landed magnates that had arisen in the Koch society during Mughal rule. By the end of the eighteenth century this claim was filtering down the ranks of the Koch society and gaining an increasing acceptability (Ray 2002:50)."(Shin 2021:34)

- "So among the mass people, the process of Hinduization was slower than in the folds of the royal family"(Sheikh 2012:252)

- "The social movement of the Rajbanshis is a historical fact. During the Census of 1872, the Rajbanshis of Bengal and some part of Assam were trying to dissociate themselves from the tribal Koches and frantically dependent entry in the Census as a distinct caste i.e "Rajbanshi".(Adhikary 2009:309)

- "In 1901, many Koches in North Bengal were returned as Rajbanshis. Many of the Rajbanshis have taken sacred thread and were prepared to use force in support of their claim to be returned as Kshatriya. He also writes "No part of the Census in 1891, 1901, 1911 aroused so much excitement as the return of caste which caused a great deal heart burning and in some were returned as kshatriya quarters with threats of disturbance of the peace. The Rajbanshis claimed to be included as Kshatriya, Bratya kshatriya, Barua kshatriya"(Adhikary 2009:65)

- "The immigrants with a strong awareness to caste started interacting with indigenous Rajbanshis in differential terms. There are numerous instances of humiliation and objectionable identities of the Rajbanshis by the other caste immigrant. Few such instances of racialism interpretation and social suppression are Nagendra Nath Basu in the early twentieth century while writing his World Encyclopedia (Biswakosh) mentioned the Rajbanshis as barbarians or mlechha and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya in Bango Dar shan moots that the Koch identity."(Adhikary 2009:163)

- The Rajbanshis also faced humiliation and objectionable identification by the caste Hindus. Few such instances of racial misinterpretation and social suppression are: Nagendranath Basu in the early twentieth century while writing his Vishwakosh (World Encyclopedia) mentioned the Rajbanshis as barbarians or (Mlechha) and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay in Bongo Darshan moots that the Koch identity cannot be synonymous with Bengali Hindu identity. The Ranjbanshis were even denied entry into the temple of Jagannath Puri by an Act of the government in the year 1911."(Hazarika 2009:277)

- "So among the mass people the process of Hinduization was slower than in the folds of the royal family. With the embracing of Hinduism, they were left with a somewhat despised name 'Koch' and adopted the name Rajbansi, a Kshatriya status which means literally 'of royal race', confined predominantly within the cultivators and the respectable classes"(Sheikh 2012:252)

- (Sheikh 2012, p. 250):"But it is surmised this was nothing but Sanscritization of the ruling family which spread the Brahminical ideas among the tribes to bring them under the pale of Hinduism. The king Biswa Singha with his tribal origin embraced Hinduism and claim Kshatriya status. He is also known as Bishu succeeded in establishing his authority, styling himself as Raja, he first claimed Rajbanshi Kshatriya status"

- "As both royal families call themselves Sivabangshi, so the mass of the Koches call themselves Rajbanshis as commented with royal families"(Adhikary 2009:63–64)

- "No part of the Census in 1891, 1901, 1911 aroused so much excitement as the return of caste which caused a great deal heart burning and in some were returned as kshatriya quarters with threats of disturbance of the peace. The Rajbanshis claimed to be included as Kshatriya, Bratya kshatriya, Barua kshatriya"(Adhikary 2009:65)

- "The Rajbanshis also used the reference of Yoginitantra, Kalika Purana, and Bhramari Tantra to establish their claim as Bratya Kshatriya or Bhanga Kshatriya."(Adhikary 2009:309)

- "The Rajbanshis claimed that they were originally to the kshatriya varna and left their original homeland and took shelter in a region called Paundradesh corresponding to the districts of Rangpur, Dinajpur, Bogra, and the adjacent areas in fear of annihilation of Parasurama, a Brahman sage. In order to hide their kshatriyas identity they gave up their sacred thread and started living with the local people and gradually came to be known as the Bhanga Kshatriyas or the fallen kshatriyas."(Adhikary 2009:167–168)

- " As both royal families call themselves Sivabangshi, so the mass of the Koches call themselves Rajbanshis as commented with royal families. Some of the Rajbanshis are now trying to prove that they are descendants of the Kshatriyas, who have taken shelter in North Bengal, being pursued by a Brahman hero Parsu Ram who extirpated the kshatriyas from the earth twenty one times. Some of them still call themselves Bhanga Kshatriyas."(Adhikary 2009:63–64)

- "Though there are certain differences in these three accounts, the common thread that binds all of them together is the effort to create a convincing myth to provide their Kshatriya origin."(Adhikary 2009, p. 168)

- "The claim to Kshatriya varna status through reinvention of some mythic tales provided some credibility to the ideological foundation of the Rajbanshi movement"(Roy 2014)

- (Adhikary 2009:311)

- "The Kshatriya samiti also had some other objectives to fulfill. It intended first, to separate the Koch and the Rajbanshi identity emphasizing the superior status of the latter; second, to legitimize the demand to include the Rajbanshis within the Kshatriya caste; third, to inculcate brahmanical values and practices among the Rajbanshis"(Hazarika 2009:277)

- ^ Das 2004, p. 560.

- Adhikary 2009, pp. 169–170.

- Das 2004, p. 561.

- "At the initial stage, the Rajbanshis caste leaders typically attempted to improve their social standing by altering their customs to resemble the ways of life of 'twice- born'. As a formal work of 'twice born' they started wearing sacred thread and adopted gotra (clan) name. They also reduced the period of mourning and ritual pollution (as ouch) from thirty to twelve days to corresponding with that of the kshatriya."(Adhikary 2009, p. 169)

- " In order to gratify their ritual rank aspiration they began to imitate the values, practices and cultural styles of ‘twice born’ castes that formed a part of Hindu Great tradition. Since 1912, a number of mass thread wearing ceremonies (Milan Kshetra) were organized in different districts by the ‘Kshatriya Samiti’ where lakhs of Rajbanshi's donned the sacred thread as a mark of Kshatriya status."(Hazarika 2009:277)

- Adhikary 2009, p. 170.

- "In their desire to be recorded as a member of high caste, they passed through at least four distinct social identities from one census to another i.e. from Koch to Rajbanshi (1872 A.D.), from Rajbanshi to Bratya/ Bhanga Kshatriya(1891), from Bratya/Bhanga Kshatriya· to Rajbanshi Kshatriya (1901,1911,1921 A.D.) and from Rajbanshi Kshatriya to only Kshatriya."(Adhikary 2009:312)

- "Today, the Koch Rajbanshi people are located in North Bengal, Assam (with a major concentration in west Assam), Garo hills of Meghalaya, Purnia, Kishanganj, and Katihar districts of Bihar, Jhapa and Biratnagar districts of Nepal, Rangpur, East Dinajpur districts and some parts of northwest Mymensingh, northern Rajshahi and Bogra districts of Bangladesh and lower parts of Bhutan (Nalini Ranjan Ray 2009)." (Roy 2014)

- Roy (2014):"Suniti Kumar Chatterji observed that Rajbanshis were Koch in origin and belonged to the larger Bodo group. They were Hinduised or semi-Hinduised and had discarded their Tibeto-Burman language, adopting northern Bengali sub-language as their tongue."

- Das, Mukherjee & Bhattacharjee (1967), p. 433: "And the various ethnological reports concur on the origin of the Rajbanshi from the Koch, the Mech and the Paliya tribes"

- "The large tract of country called Mechpara in the Gowalparah District no doubt took its name from them, and the proprietor is a Mech; but he and most of his people repudiate this origin and call themselves Rajbangsis"(Mitra 1953:224)

- Debnath, Monojit; Palanichamy, Malliya G.; Mitra, Bikash; Jin, Jie-Qiong; Chaudhuri, Tapas K.; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2011). "Y-chromosome haplogroup diversity in the sub-Himalayan Terai and Duars populations of East India". Journal of Human Genetics. 56 (11): 765–771. doi:10.1038/jhg.2011.98. ISSN 1435-232X. PMID 21900945. S2CID 2735604.

- "On the other hand, there are Rajbanshi in Midnapur, 24 Paraganas, Hoogly and Nadia district who may not be of the same stock and do not speak this language"(Adhikary 2009:138)

- "Thompson states, "The Rajbanshis are the indigenous people of Northern Bengal and the third Largest Hindu Caste in the province. Their total number has been exaggerated by the fact that a member of fisherman caste in Mymensingh, Nadia and Murshidabad returned themselves as Rajbanshis."(Adhikary 2009:65)

- Barman, Rup Kumar (2015). "Culture of Difference in Ethnic Identity: A new Look on the transition of Caste identity into Cultural identity of the Rajbanshis of Northern Bengal and Lower Assam" (PDF). The Mirror. 2: 56–69.

- Barman, Rup Kumar. "A new Look on the transition of Caste identity into Cultural identity of the Rajbanshis of Northern Bengal and Lower Assam" (PDF). The Mirror: 56–70.

- Singha, Surjit; Singha, Ranjit (2019). Sustainable Entrepreneurship in North East India (1 ed.). Bulgaria: Tsenov Academic Publishing House. pp. 161–187. ISBN 9789542317524. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Sanyal, Charu Chandra (1965). The Rajbansis of North Bengal. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society.

- Population Monograph of Nepal, Volume II

- 2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report

References

- Nandi, Rajib (24 June 2014). "Spectacles of Ethnographic and Historical Imaginations: Kamatapur Movement and the Rajbanshi Quest to Rediscover their Past and Selves". History and Anthropology. 25 (5): 571–591. doi:10.1080/02757206.2014.928776. ISSN 0275-7206. S2CID 144397875.

- Adhikary, Madhab Chandra (2009). Ethno Cultural Identity Crisis of the Rajbanshis of North Eastern Part of india and Nepal and Bangladesh during the period of 1891 to 1979 (PhD). University of North Bengal. hdl:10603/137486.

- Adhikary, Madhab Chandra (2010). "Socio-political movement in post colonial North Bengal: A case study of the Rajbanshis". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 71: 1233–1242. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44147592.

- Chatterji, S.K (1951). Kirata-Jana-Krti. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society.

- Das, Jitendra Nath (2004). "The backwardness of the Rajbansis and the Rajbansi kshatriya movement (1891-1936)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 65: 559–563. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44144770.

- Das, S. R.; Mukherjee, D. P.; Bhattacharjee, P. N. (1967). "Survey of the Blood Groups and PTC Taste Among the Rajbanshi Caste of West Bengal (ABO, MNS, Rh, Duffy and Diego)". Acta Genetica et Statistica Medica. 17 (5): 433–445. doi:10.1159/000152094. JSTOR 45103942. PMID 6072621.

- Gogoi, Jahnavi (2002). Agrarian System of Medieval Assam. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

- Hazarika, S. (2009), Basu, S (ed.), "Unrest and Displacement: Rajbanshis in North Bengal", The Fleeing People of South Asia: Selections from Refugee Watch, Anthem Press: 274–282, doi:10.7135/UPO9781843317784.037, ISBN 9781843317784

- Jacquesson, François (2008), "Discovering Boro-Garo: History of an analytical and descriptive linguistic category", European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, 32: 14–49

- Kondakov, Alexander (2013). Hyslop, Gwendolyn; Morey, Stephen; Post, Mark W (eds.). "Koch dialects of Meghalaya and Assam: A sociolinguistic survey". North East Indian Linguistics. 5. Cambridge University Press India: 3–59. doi:10.1017/9789382993285.003. ISBN 9789382993285.

- Mitra, A (1953). The Tribes and Castes of West Bengal. Alipore, West bengal: West Bengal Government Press.

- Nath, D. (1989), History of the Koch Kingdom, C. 1515-1615, Mittal Publications, pp. 5–6, ISBN 8170991099

- Ramirez, Philippe (2014). People of the Margins - Across Ethnic Boundaries in North-East India.

- Roy, Hirokjeet (2014), "Politics of Janajatikaran: Koch Rajbanshis of Assam", Economic and Political Weekly, 49 (47)

- Roy, Kapil Chandra (2018), "Demand for Scheduled Tribe Status by Koch-Rajbongshis", Economic and Political Weekly, 53 (44)

- Sheikh, Amiruzzaman (2012). "The 16th century Koch kingdom: Evolving patterns of sankritization". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 249–254. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44156212.

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2021). "Sword and Words: A Conflict Between Kings and Brahmins in the Bengal Frontier, Kāmatāpur 15th-16th Centuries". Journal of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums. 3. Government of West Bengal: 21–36.

- Wilson, Margot; Bashir, Kamran (16 March 2016). "'King's inheritors': understanding the ethnic discourse on the Rajbanshi as an indigenous community". Social Identities. 22 (5): 455–470. doi:10.1080/13504630.2016.1148594. ISSN 1350-4630. S2CID 146814921.