| Revision as of 19:14, 10 July 2018 edit86.12.247.105 (talk) →Origin of the currently recognized Seven Deadly SinsTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:57, 24 December 2024 edit undo2a02:c7c:b053:5800:404d:304b:ddc5:e4d6 (talk) →Lust | ||

| (900 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Set of vices in Christian theology}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Mortal sin}} | |||

| {{ |

{{other uses|Seven deadly sins (disambiguation)|Deadly Sins (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{distinguish|Mortal sin}} | |||

| {{redirect|Deadly sins|other uses|Deadly Sins (disambiguation){{!}}Deadly Sins}} | |||

| ]'s '']'']]] | ]'s '']'']] | ||

| ] | |||

| {{Catholic philosophy}} | {{Catholic philosophy}} | ||

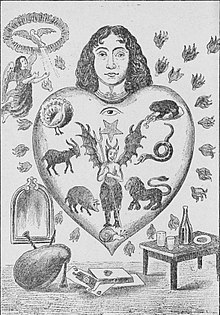

| The '''seven deadly sins''', also known as the '''capital vices''' or '''cardinal sins''', is a grouping and classification of ]s within Christian teachings.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook|last=Tucker|first=Shawn|publisher=Cascade|year=2015|isbn=1625647182|location=|pages=}}</ref> Behaviours or habits are classified under this category if they directly give birth to other immoralities.<ref name="Aquinas">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YiJCBAAAQBAJ|title=Summa Theologica (All Complete & Unabridged 3 Parts + Supplement & Appendix + interactive links and annotations)|last=Aquinas|first=Thomas|date=2013-08-20|publisher=e-artnow|isbn=9788074842924|language=en}}</ref> According to the standard list, they are ''']''', ''']''', ''']''', ''']''', ''']''', ''']''' and ''']''',<ref name="Aquinas"/> which are also contrary to the ]. These ] are often thought to be abuses or excessive versions of one's natural faculties or passions (for example, gluttony abuses one's desire to eat). | |||

| The '''seven deadly''' '''sins''' (also known as the '''capital''' '''vices''' or '''cardinal sins''') function as a grouping classification of major vices within the teachings of ].<ref name="Tucker-2015">{{Cite book |title=The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook |last=Tucker |first=Shawn |publisher=Cascade |year=2015 |isbn=978-1625647184}}</ref> According to the standard list, the seven deadly sins in Christianity are ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| This classification originated with the ], especially ], who identified seven or eight evil thoughts or spirits that one needed to overcome.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Evagrius of Pontus: The Greek Ascetic Corpus translated by Robert E. Sinkewicz.|last=Evagrius|first=|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2006|isbn=0199297088|location=Oxford and New York|pages=}}</ref> Evagrius' pupil ], with his book ''The Institutes,'' brought the classification to Europe,<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Institutes|last=Cassian|first=John|publisher=Newman Press of the Paulist Press|year=2000|isbn=0809105225|location=|pages=}}</ref> where it became fundamental to Catholic confessional practices as evident in penitential manuals, sermons like "]" from Chaucer's ''],'' and artworks like Dante's ] (where the penitents of Mount Purgatory are depicted as being grouped and penanced according to the worst capital sin they committed). The Catholic Church used the concept of the deadly sins in order to help people curb their inclination towards evil before dire consequences and misdeeds could occur; the leader-teachers especially focused on pride (which is thought to be the sin that severs the soul from Grace,<ref name=":32"/> and the one that is representative and the very essence of all evil) and greed, both of which are seen as inherently sinful and as underlying all other sins to be prevented. To inspire people to focus on the seven deadly sins, the vices are discussed in treatises and depicted in paintings and sculpture decorations on Catholic churches as well as older textbooks.<ref name=":0"/> | |||

| In Christianity, the classification of deadly sins into a group of seven originated with ], and continued with ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Seven Deadly Sins |url=https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/the-seven-deadly-sins |access-date=2023-09-30 |website=Catholic Answers}}</ref> The concepts of the sins involved were in part based on Greco-Roman and Biblical antecedents. Later, the concept of seven deadly sins evolved further, based upon historical context based upon the Latin language of the Roman Catholic Church, though with a significant influence from the Greek language and associated religious traditions. Knowledge of the seven deadly sin concept is known through discussions in various treatises and also depictions in paintings and sculpture, for example architectural decorations on certain churches of certain Catholic ] and also from certain older textbooks.<ref name="Tucker-2015"/> Further information has been derived from patterns of ]. | |||

| Subsequently, over the centuries into modern times, the idea of sins (especially seven in number) has influenced or inspired various streams of religious and philosophical thought, fine art painting, and modern popular culture media such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| ] = avarice; ] = envy; ] = wrath; ] = sloth; ] = gluttony; ] = lust; ] = pride)]] | |||

| === Origin of the currently recognized seven deadly sins === | |||

| === Greco-Roman antecedents === | |||

| These "evil thoughts" can be categorized as follows:<ref name="Refoule67" /> | |||

| While the seven deadly sins as we know them did not originate with the Greeks or Romans, there were ancient precedents for them. ] '']'' lists several positive, healthy human qualities, excellences, or ]s. Aristotle argues that for each positive quality there are two negative vices that are found on each extreme of the virtue. Courage, for example, is the human excellence or virtue in facing fear and risk. Excessive courage makes one rash, while a deficiency of courage makes one cowardly. This principle of virtue found in the middle or "mean" between excess and deficiency is Aristotle's notion of the ]. Aristotle lists virtues like courage, temperance or self-control, generosity, "greatness of soul," proper response to anger, friendliness, and wit or charm. | |||

| * physical (thoughts produced by the nutritive, sexual, and acquisitive appetites) | |||

| Roman writers like ] extolled the value of virtue while listing and warning against vices. His first epistles says that "to flee vice is the beginning of virtue, and to have got rid of folly is the beginning of wisdom."<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Seven Deadly Sins: Their origin in the spiritual teaching of Evagrius the Hermit|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O3WpAwAAQBAJ|publisher=SPCK|date=2013-04-23|isbn=9780281062997|first=Angela|last=Tilby}}</ref> | |||

| * emotional (thoughts produced by depressive, irascible, or dismissive moods) | |||

| * mental (thoughts produced by jealous/envious, boastful, or hubristic states of mind) | |||

| The fourth-century ] ] reduced the{{which|date=September 2024}} nine ''logismoi''{{clarify|date=September 2024}} to eight, as follows:<ref name="Pontico">Evagrio Pontico, ''Gli Otto Spiriti Malvagi'', trans., Felice Comello, Pratiche Editrice, Parma, 1990, p.11-12.</ref><ref name="Evagrius">{{Cite book |last=Evagrius |title=The Greek Ascetic Corpus |date=22 June 2006 |publisher=] |isbn=0199297088 |location=Oxford and New York |translator-last=Sinkewicz. |translator-first=Robert E. |author-link=Evagrius Ponticus}}</ref> | |||

| ] = avarice; ] = envy; ] = wrath; ] = sloth; ] = gluttony; ] = lust; ] = pride).]] | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Γαστριμαργία}} ({{transliteration|grc|gastrimargia}}) ] | |||

| === Origin of the currently recognized Seven Deadly Sins === | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Πορνεία}} ({{transliteration|grc|porneia}}) ], ] | |||

| The modern concept of the seven deadly sins is linked to the works of the fourth-century ] ], who listed eight ''evil thoughts'' in ] as follows:<ref name="Pontico">Evagrio Pontico, ''Gli Otto Spiriti Malvagi'', trans., Felice Comello, Pratiche Editrice, Parma, 1990, p.11-12.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Evagrius of Pontus: The Greek Ascetic Corpus|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=2006-06-22|location=Oxford|isbn=9780199297085}}</ref> | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Φιλαργυρία}} ({{transliteration|grc|philargyria}}) ] | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Λύπη}} ({{transliteration|grc|lypē}}) ], rendered in the '']'' as ''envy'', sadness at another's good fortune | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Ὀργή}} ({{transliteration|grc|orgē}}) ] | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Ἀκηδία}} ({{transliteration|grc|akēdia}}) ], rendered in the '']'' as ] | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Κενοδοξία}} ({{transliteration|grc|kenodoxia}}) ] | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Ὑπερηφανία}} ({{transliteration|grc|hyperēphania}}) ], sometimes rendered as ''self-overestimation'', ''arrogance'', or ''grandiosity''<ref>In the of the '']'' by Palmer, Ware and Sherrard.</ref> | |||

| Evagrius's list was translated into the Latin of Western Christianity in many writings of ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf211.iv.iii.html |title=NPNF-211. Sulpitius Severus, Vincent of Lerins, John Cassian – Christian Classics Ethereal Library |website=www.ccel.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |edition=First |title=The Institutes |publisher=Newman Press of the Paulist Press |date=3 January 2000 |location=New York |isbn=9780809105229 |first=John |last=Cassian |author-link=John Cassian}}</ref> thus becoming part of the Western tradition's spiritual ] or ] as follows:<ref name="Refoule67">Refoule, F. (1967) "Evagrius Ponticus," In ''New Catholic Encyclopaedia,'' Vol. 5, pp. 644f, Staff of Catholic University of America, Eds., New York: McGraw-Hill.</ref> | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Γαστριμαργία}} (''gastrimargia'') gluttony | |||

| # {{lang| |

# {{lang|la|Gula}} (]) | ||

| # {{lang| |

# {{lang|la|Luxuria/Fornicatio}} (], ]) | ||

| # {{lang|la|Avaritia}} (]) | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Ὑπερηφανία}} (''hyperēphania'') ] – sometimes rendered as ''self-overestimation''<ref>In the of the '']'' by Palmer, Ware, and Sherrard.</ref> | |||

| # {{lang|la|Tristitia}} (]/]/despondency) | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Λύπη}} (''lypē'') ] – in the '']'', this term is rendered as ''envy,'' sadness at another's good fortune | |||

| # {{lang| |

# {{lang|la|Ira}} (]) | ||

| # {{lang| |

# {{lang|la|Acedia}} (]) | ||

| # {{lang|la|Vanagloria}} (vainglory) | |||

| # {{lang|grc|Ἀκηδία}} (''akēdia'') ] – in the ''Philokalia'', this term is rendered as ] | |||

| # {{lang|la|Superbia}} (]) | |||

| In AD 590, ] revised the list to form a more common list.<ref>"For pride is the root of all evil, of which it is said, as Scripture bears witness; Pride is the beginning of all sin. But seven principal vices, as its first progeny, spring doubtless from this poisonous root, namely, vain glory, envy, anger, melancholy, avarice, gluttony, lust." '''Gregory the Great, '''</ref> Gregory combined {{lang|la|tristitia}} with {{lang|la|acedia}} and {{lang|la|vanagloria}} with {{lang|la|superbia}}, adding ''envy'', which is {{lang|la|invidia}} in Latin.<ref name="DelCogliano-2014">{{Cite book|title=Gregory the Great: Moral Reflections on the Book of Job, Volume 1|publisher=Cistercian Publications|date=18 November 2014|isbn=9780879071493|first=Mark|last=DelCogliano}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook|publisher=Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers|date=24 February 2015|first=Shawn R.|last=Tucker}}</ref> (It is interesting to note that Pope Gregory's list corresponds exactly to the traits described in Pirkei Avot as "removing one from the world." See ] 2:11, 3:10, 4:21 and the ]'s commentary to Aggadot ] 4b.)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://seforimblog.com/2016/03/traditional-jewish-source-for-seven/?print=print | title=Traditional Jewish source for the "Seven Deadly Sins" - the Seforim Blog }}</ref> ] uses and defends Gregory's list in his '']'', although he calls them the "capital sins" because they are the head and form of all the other sins.<ref>{{Cite web|title=SUMMA THEOLOGICA: The cause of sin, in respect of one sin being the cause of another Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 84; I-II,84,3)|url=http://www.newadvent.org/summa/2084.htm#article4|website=www.newadvent.org|access-date=4 December 2015}}</ref> Christian denominations, such as the ],<ref name="Armentrout2000">{{cite book|last=Armentrout|first=Don S.|title=An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians|date=1 January 2000|publisher=Church Publishing, Inc.|language=en |isbn=9780898697018|page=479}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lutheranhour.org/sermon.asp?articleid=648&mode=print|title=Mighty Menacin' Midianites|last=Lessing|first=Reed|date=25 August 2002|publisher=The Lutheran Hour|language=en|access-date=26 March 2017}}</ref> and ],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ucmpage.org/articles/rspeidel.htm|title=What Would a United Methodist Jesus Do?|last=Speidel|first=Royal|publisher=UCM|language=en|access-date=26 March 2017|quote=Thirdly, the United Methodist Jesus reminds us to confess our sins. How long has it been since you have heard reference to the seven deadly sins: pride, gluttony, sloth, lust, greed, envy and anger?|archive-date=25 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160425124302/http://ucmpage.org/articles/rspeidel.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> still retain this list, and modern evangelists such as ] have explicated the seven deadly sins.<ref>{{cite book|title=The American Lutheran, Volumes 39–40|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KaHmAAAAMAAJ|year=1956|publisher=American Lutheran Publicity Bureau|language=en |page=332|quote=The world-renowned Evangelist, Billy Graham, presents in this volume an excellent analysis of the seven deadly sins which he enumerates as pride, anger, envy, impurity, gluttony, avarice and slothfulness.}}</ref> | |||

| They were taken to account of the smiley men and were but into the category.(largely due to the writings of ]),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf211.iv.iii.html|title=NPNF-211. Sulpitius Severus, Vincent of Lerins, John Cassian - Christian Classics Ethereal Library|website=www.ccel.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|edition=First|title=The Institutes|publisher=Newman Press of the Paulist Press|date=2000-01-03|location=New York|isbn=9780809105229|first=St John|last=Cassian}}</ref> thus becoming part of the Western tradition's spiritual ] (or ]), as follows:<ref name="Refoule67">Refoule, F. (1967) "Evagrius Ponticus," In ''New Catholic Encyclopaedia,'' Vol. 5, pp. 644f, Staff of Catholic University of America, Eds., New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill.</ref> | |||

| # {{lang|la|Gula}} (gluttony) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Luxuria/Fornicatio}} (lust, fornication) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Avaritia}} (avarice/greed) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Superbia}} (pride, hubris) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Tristitia}} (]/]/]) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Ira}} (wrath) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Vanagloria}} (]) | |||

| # {{lang|la|Acedia}} (sloth) | |||

| ==Historical and modern definitions, views, and associations== | |||

| These "evil thoughts" can be categorized into three types:<ref name=Refoule67/> | |||

| According to ] ], the seven deadly sins are seven ways of ].<ref name="Manning">{{Cite book|title=Sin and Its consequences|last=Manning|first=Henry Edward}}</ref> The Lutheran divine ], who contributed to the development of Lutheran systematic theology, implored clergy to remind the faithful of the seven deadly sins.<ref name="Chemnitz2007">{{cite book |author1=] |title=Ministry, Word, and Sacraments: An Enchiridion; The Lord's Supper; The Lord's Prayer |date=2007 |publisher=Concordia Publishing House |isbn=978-0-7586-1544-2 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Listed in order of increasing severity as per Pope Gregory I, 6th-century A.D., the seven deadly sins are as follows: | |||

| * lustful appetite (gluttony, fornication, and avarice) | |||

| * irascibility (wrath) | |||

| * mind corruption (vainglory, sorrow, pride, and discouragement) | |||

| In AD 590 ] revised this list to form the more common list. Gregory combined ''tristitia'' with ''acedia'', and ''vanagloria'' with ''superbia'', and added ''envy,'' in Latin, ''invidia''.<ref name=":7">{{Cite book|title=Gregory the Great: Moral Reflections on the Book of Job, Volume 1|publisher=Cistercian Publications|date=2014-11-18|isbn=9780879071493|first=Mark|last=DelCogliano}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook|publisher=Cascade Books, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers|date=2015-02-24|first=Shawn R.|last=Tucker}}</ref> Gregory's list became the standard list of sins. ] uses and defends Gregory's list in his '']'' although he calls them the "capital sins" because they are the head and form of all the others.<ref>{{Cite web|title=SUMMA THEOLOGICA: The cause of sin, in respect of one sin being the cause of another Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 84; I-II,84,3)|url=http://www.newadvent.org/summa/2084.htm#article4|website=www.newadvent.org|accessdate=2015-12-04}}</ref> The ],<ref name="Armentrout2000">{{cite book|last=Armentrout|first=Don S.|title=An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians|date=1 January 2000|publisher=Church Publishing, Inc.|language=English |isbn=9780898697018|page=479}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lutheranhour.org/sermon.asp?articleid=648&mode=print|title=Mighty Menacin' Midianites|last=Lessing|first=Reed|date=25 August 2002|publisher=The Lutheran Hour|language=English|accessdate=26 March 2017}}</ref> and ],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ucmpage.org/articles/rspeidel.htm|title=What Would a United Methodist Jesus Do?|last=Speidel|first=Royal|publisher=UCM|language=English|accessdate=26 March 2017|quote=Thirdly, the United Methodist Jesus reminds us to confess our sins. How long has it been since you have heard reference to the seven deadly sins: pride, gluttony, sloth, lust, greed, envy and anger? }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://ywmovement.org/life-of-a-disciple-in-the-world-7-seven-deadly-sins-lust/|title=Life Of A Disciple In The World 7- Seven Deadly Sins: Lust|publisher=United Methodist YouthWorker Movement|language=English|accessdate=26 March 2017}}</ref> among other Christian denominations, continue to retain this list. Moreover, modern day evangelists, such as ] have explicated the seven deadly sins.<ref>{{cite book|title=The American Lutheran, Volumes 39-40|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KaHmAAAAMAAJ|year=1956|publisher=American Lutheran Publicity Bureau|language=English |page=332|quote=The world-renowned Evangelist, Billy Graham, presents in this volume an excellent analysis of the seven deadly sins which he enumerates as pride, anger, envy, impurity, gluttony, avarice, and slothfulness.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Historical and modern definitions, views and associations== | |||

| Most of the capital sins, with the sole exception of sloth, are defined by ] as perverse or corrupt versions of love for something or another: lust, gluttony, and greed are all excessive or disordered love of good things; sloth is a deficiency of love; wrath, envy, and pride are perverted love directed toward other's harm.<ref name="DLSintro652">], ''Purgatory'', Introduction, pp. 65–67 (Penguin, 1955).</ref> In the seven capital sins are seven ways of eternal death.<ref name=":32">{{Cite book|title=Sin and Its consequences|last=Manning|first=Henry Edward|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=}}</ref> The capital sins from lust to envy are generally associated with pride, which has been labeled as the father of all sins, etc. | |||

| === Lust === | === Lust === | ||

| {{Main|Lust}}Lust or lechery is intense longing. It is usually thought of as intense or unbridled ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lust|title=Definition of LUST|website=www.merriam-webster.com|access-date=4 May 2016}}</ref> which may lead to ] (including ], ], ]), and other sinful and sexual acts; oftentimes, however, it can also mean other forms of unbridled desire, such as for money, or power. ] explains that the impurity of lust transforms one into "a slave of the ]".<ref name="Manning"/> | |||

| {{Main article|Lust}} | |||

| ], whom ]'s ] describes as ] for fornication. (], 1819)]] | |||

| '''Lust''', or '''lechery''' (Latin, "''luxuria''" (carnal)), is intense longing. It is usually thought of as intense or unbridled sexual desire,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lust|title=Definition of LUST|website=www.merriam-webster.com|access-date=2016-05-04}}</ref> which leads to ], ], ], ], and other immoral sexual acts. However, lust could also mean simply desire in general; thus, lust for money, power, and other things are sinful. In accordance with the words of ], the impurity of lust transforms one into "a slave of the devil".<ref name=":32"/> | |||

| Lust, if not managed properly, can subvert propriety.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book|title=Lust:The Seven Deadly SIns|last=Blackburn|first=Simon|publisher=|year=|isbn=0-19-516200-5|location=|pages=}}</ref> | |||

| German ] ] wrote as follows:<ref name=":5"/> | |||

| {{Quote|text="Lust is the ultimate goal of almost all human endeavour, exerts an adverse influence on the most important affairs, interrupts the most serious business, sometimes for a while confuses even the greatest minds, does not hesitate with its trumpery to disrupt the negotiations of statesmen and the research of scholars, has the knack of slipping its love-letters and ringlets even into ministerial portfolios and philosophical manuscripts".|sign=|source=}} | |||

| Dante defined lust as the disordered love for individuals, thus possessing at least the redeeming feature of mutuality, unlike the graver sins, which constitute an increasingly agonised focussing upon the solitary self ( a process begun with the more serious sin of gluttony ).<ref>Dante, ''Hell' (1975) p. 101; Dante, ''Purgatory'' (1971) p. 67 and p. 202''</ref> It is generally thought to be the least serious capital sin<ref name="DLSintro652"/><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uf62BQAAQBAJ|title=William Blake's Illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy: A Study of the Engravings, Pencil Sketches and Watercolors|last=Pyle|first=Eric|date=2014-12-31|publisher=McFarland|isbn=9781476617022|language=en}}</ref> as it is an abuse of a faculty that humans share with animals, and sins of the flesh are less grievous than spiritual sins ( love excessive, not love turning ever further awry toward hatred of man and God ). <ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=VeP7kg-blnIC&pg=PA1819&dq=lust+summa+theologica&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi4-YPy-KTNAhVh36YKHRrvBRQQuwUILjAC#v=onepage&q=lust%2520summa%2520theologica&f=false|title=Summa Theologica, Volume 4 (Part III, First Section)|last=Aquinas|first=St Thomas|date=2013-01-01|publisher=Cosimo, Inc.|isbn=9781602065604|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Lust is generally thought to be the least serious capital sin.<ref name="DLSintro652">], ''Purgatory'', Introduction, pp. 65–67 (Penguin, 1955).</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uf62BQAAQBAJ|title=William Blake's Illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy: A Study of the Engravings, Pencil Sketches and Watercolors|last=Pyle|first=Eric|date=31 December 2014|publisher=McFarland|isbn=9781476617022|language=en}}</ref> Thomas Aquinas considers it an abuse of a faculty that humans share with animals and sins of the flesh are less grievous than spiritual sins.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VeP7kg-blnIC&q=lust%2520summa%2520theologica&pg=PA1819|title=Summa Theologica, Volume 4 (Part III, First Section)|last=Aquinas|first=St Thomas|date=1 January 2013|publisher=Cosimo|isbn=9781602065604|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In Dante's ''Purgatorio'', the penitents walk deliberately through the purifying flames of the uppermost of the terraces of Mount Purgatory so as to purge themselves of lustful thoughts and feelings and finally win the right to reach the Earthly Paradise at the summit. In Dante's '']'', unforgiven souls guilty of the sin of lust are whirled around for all eternity in a perpetual tempest, symbolic of the passions by which, through lack of self-control, they were buffeted helplessly about in their earthly lives. | |||

| === Gluttony === | === Gluttony === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Gluttony}} | ||

| ]'' (], 1896)]] | ], 1896)]] | ||

| Gluttony is the overindulgence and ] of anything to the point of waste. The word derives from the Latin {{lang|la|gluttire}}, meaning to gulp down or swallow.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Latin Definition for: gluttio, gluttire, -, – (ID: 21567) – Latin Dictionary and Grammar Resources – Latdict |url=https://latin-dictionary.net/definition/21567/gluttio-gluttire |access-date=2022-10-10 |website=latin-dictionary.net}}</ref> One reason for its condemnation is that the gorging of the prosperous may leave the needy hungry.<ref name="Okholm 2000">Okholm, Dennis. . '']'', Vol. 44, No. 10, 11 September 2000, p.62</ref> | |||

| Medieval church leaders such as ] took a more expansive view of gluttony,<ref name="Okholm 2000"/> arguing that it could also include an obsessive anticipation of meals and overindulgence in delicacies and costly foods. Aquinas also listed five forms of gluttony:<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06590a.htm|title=Gluttony|encyclopedia=]}}</ref> | |||

| In Christianity, it is considered a sin if the excessive desire for food causes it to be withheld from the needy.<ref name="Okholm 2000">Okholm, Dennis. . '']'', Vol. 44, No. 10, September 11, 2000, p.62</ref> | |||

| * {{lang|la|Laute}} – eating too expensively | |||

| Because of these scripts, gluttony can be interpreted as ]; essentially placing concern with one's own impulses or interests above the well-being or interests of others.{{Original research inline|date=June 2016}} | |||

| * {{lang|la|Studiose}} – eating too daintily | |||

| * {{lang|la|Nimis}} – eating too much | |||

| During times of ], ], and similar periods when food is scarce, it is possible for one to indirectly kill other people through starvation just by eating too much or even too soon. | |||

| * {{lang|la|Praepropere}} – eating too soon | |||

| * {{lang|la|Ardenter}} – eating too eagerly | |||

| Medieval church leaders (e.g., ]) took a more expansive view of gluttony,<ref name="Okholm 2000"/> arguing that it could also include an obsessive anticipation of meals, and the constant eating of delicacies and excessively costly foods.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06590a.htm|title=Gluttony|work=]}}</ref> Aquinas went so far as to prepare a list of five ways to commit gluttony, comprising: | |||

| * ''Laute'' – eating too expensively | |||

| * ''Studiose'' – eating too daintily | |||

| * ''Nimis'' – eating too much | |||

| * ''Praepropere'' – eating too soon | |||

| * ''Ardenter'' – eating too eagerly | |||

| Of these, ''ardenter'' is often considered the most serious, since it is extreme attachment to the pleasure of mere eating, which can make the committer eat impulsively; absolutely and without qualification live merely to eat and drink; lose attachment to health-related, social, intellectual, and spiritual pleasures; and lose proper judgement{{Original research inline|date=June 2016}}: an example is ] selling his birthright for ordinary food of bread and pottage of lentils. His punishment was that of the "profane person . . . who, for a morsel of meat sold his birthright." We learn that "he found no place for repentance, though he sought it carefully, with tears." {{bibleref2c|Gen|25:30|NASB}} | |||

| === Greed === | === Greed === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Greed}} | ||

| ]'' by ] |

]'' (1909) by ]]] | ||

| ]] | |||

| '''Greed''' (Latin, {{lang|la|avaritia}}), also known as '''avarice, cupidity''', or '''covetousness''', is, like lust and gluttony, a sin of desire. However, greed (as seen by the Church) is applied to an artificial, rapacious desire and pursuit of material possessions. Thomas Aquinas wrote, "Greed is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things." In Dante's Purgatory, the penitents were bound and laid face down on the ground for having concentrated excessively on earthly thoughts{{citation needed|date=February 2017}}. ]ing of materials or objects, ] and ], especially by means of ], ], or ] of ] are all actions that may be inspired by Greed. Such misdeeds can include ], where one attempts to purchase or sell ], including ] and, therefore, positions of authority in the Church hierarchy. | |||

| In the words of Henry Edward, avarice "plunges a man deep into the mire of this world, so that he makes it to be his god |

In the words of Henry Edward Manning, avarice "plunges a man deep into the mire of this world, so that he makes it to be his god".<ref name="Manning"/> | ||

| As defined outside Christian writings, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs, especially with respect to ].<ref>{{cite |

As defined outside Christian writings, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs, especially with respect to ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/greed|title=greed| encyclopedia=American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language|edition=5th|year=2016|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|via=The Free Dictionary|access-date=4 February 2019}}</ref> Aquinas considers that, like pride, it can lead to evil.<ref name="Aquinas">{{Cite book |last=Aquinas |first=Thomas |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YiJCBAAAQBAJ |title=Summa Theologica (All Complete & Unabridged 3 Parts + Supplement & Appendix + interactive links and annotations) |date=20 August 2013 |publisher=e-artnow |isbn=9788074842924 |language=en |author-link=St Thomas Aquinas}}</ref> | ||

| === Sloth === | === Sloth === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Sloth (deadly sin)}} | ||

| ]'' by ], ] | ]'' (1624) by ], ]]] | ||

| Sloth refers to many related ideas, dating from antiquity and including mental, spiritual, pathological, and physical states.<ref name="Lyman-1989">{{Cite book|title=The Seven Deadly Sins: Society and Evil|last=Lyman|first=Stanford|year=1989|isbn=0-930390-81-4|pages=5|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield }}</ref> It may be defined as absence of interest or habitual disinclination to exertion.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.dictionary.com/browse/sloth?s=t|title=the definition of sloth|website=Dictionary.com|access-date=3 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ]] | |||

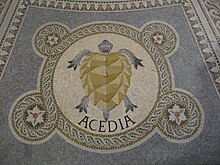

| '''Sloth''' (Latin, ''tristitia'' or '''{{lang|la|]}}''' ("without care")) refers to a peculiar jumble of notions, dating from antiquity and including mental, spiritual, pathological, and physical states.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title=The Seven Deadly Sins: Society and Evil|last=Lyman|first=Stanford|publisher=|year=|isbn=0-930390-81-4|location=|pages=5}}</ref> It may be defined as absence of interest or habitual disinclination to exertion.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.dictionary.com/browse/sloth?s=t|title=the definition of sloth|website=Dictionary.com|access-date=2016-05-03}}</ref> | |||

| In his ''Summa Theologica'', ] defined sloth as "sorrow about spiritual good".<ref name="Aquinas"/> | In his ''Summa Theologica'', ] defined sloth as "sorrow about spiritual good".<ref name="Aquinas"/> | ||

| The scope of sloth is wide.<ref name=" |

The scope of sloth is wide.<ref name="Lyman-1989"/> Spiritually, ''acedia'' first referred to an affliction attending religious persons, especially monks, wherein they became indifferent to their duties and obligations to ]. Mentally, ''acedia'' has a number of distinctive components; the most important of these is affectlessness, a lack of any feeling about self or other, a mind-state that gives rise to boredom, rancor, apathy, and a passive inert or sluggish mentation. Physically, ''acedia'' is fundamentally associated with a cessation of motion and an indifference to work; it finds expression in ], idleness, and indolence.<ref name="Lyman-1989"/> | ||

| Sloth includes ceasing to utilize the seven gifts of grace given by the ] (], ], |

Sloth includes ceasing to utilize the seven gifts of grace given by the ] (], ], Counsel, ], ], ], and ]); such disregard may lead to the slowing of spiritual progress towards eternal life, the neglect of manifold duties of ] towards the ], and animosity towards those who love God.<ref name="Manning"/> | ||

| Unlike the other seven deadly sins, which are sins of committing immorality, sloth is a sin of omitting responsibilities. It may arise from any of the other capital vices; for example, a son may omit his duty to his father through anger. The state and habit of sloth is a mortal sin, while the habit of the soul tending towards the last mortal state of sloth is not mortal in and of itself except under certain circumstances.<ref name="Manning"/> | |||

| Sloth has also been defined as a failure to do things that one should do. By this definition, evil exists when "good" people fail to act. | |||

| Emotionally, and cognitively, the evil of ''acedia'' finds expression in a lack of any feeling for the world, for the people in it, or for the self. ''Acedia'' takes form as an alienation of the sentient self first from the world and then from itself. The most profound versions of this condition are found in a withdrawal from all forms of participation in or care for others or oneself, but a lesser yet more noisome element was also noted by theologians. Gregory the Great asserted that, "from ''tristitia'', there arise malice, rancour, cowardice, despair". Chaucer also dealt with this attribute of ''acedia'', counting the characteristics of the sin to include despair, somnolence, idleness, tardiness, negligence, laziness, and ''wrawnesse'', the last variously translated as "anger" or better as "peevishness". For Chaucer, human's sin consists of languishing and holding back, refusing to undertake works of goodness because, they tell themselves, the circumstances surrounding the establishment of good are too grievous and too difficult to suffer. ''Acedia'' in Chaucer's view is thus the enemy of every source and motive for work.<ref name="Lyman">{{Cite book|title=The Seven Deadly Sins: Society and Evil|last=Lyman|first=Stanford|pages=6–7}}</ref> | |||

| ] (1729–1797) wrote in '']'' (II. 78) "No man, who is not inflamed by vain-glory into enthusiasm, can flatter himself that his single, unsupported, desultory, unsystematic endeavours are of power to defeat the subtle designs and united Cabals of ambitious citizens. When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle." | |||

| Sloth subverts the livelihood of the body, taking no care for its day-to-day provisions, and slows down the mind, halting its attention to matters of great importance. Sloth hinders the man in his righteous undertakings and thus becomes a terrible source of human's undoing.<ref name="Lyman"/> | |||

| Unlike the other capital sins, which are sins of committing immorality, sloth is a sin of omitting responsibilities. It may arise from any of the other capital vices; for example, a son may omit his duty to his father through anger. While the state and habit of sloth is a mortal sin, the habit of the soul tending towards the last mortal state of sloth is not mortal in and of itself except under certain circumstances.<ref name=":32"/> | |||

| Emotionally and cognitively, the evil of ''acedia'' finds expression in a lack of any feeling for the world, for the people in it, or for the self. ''Acedia'' takes form as an alienation of the sentient self first from the world and then from itself. Although the most profound versions of this condition are found in a withdrawal from all forms of participation in or care for others or oneself, a lesser but more noisome element was also noted by theologians. From ''tristitia'', asserted Gregory the Great, "there arise malice, rancour, cowardice, despair..." Chaucer, too, dealt with this attribute of ''acedia'', counting the characteristics of the sin to include despair, somnolence, idleness, tardiness, negligence, indolence, and ''wrawnesse'', the last variously translated as "anger" or better as "peevishness". For Chaucer, human's sin consists of languishing and holding back, refusing to undertake works of goodness because, he/she tells him/her self, the circumstances surrounding the establishment of good are too grievous and too difficult to suffer. ''Acedia'' in Chaucer's view is thus the enemy of every source and motive for work.<ref name=":4">{{Cite book|title=The Seven Deadly Sins: Society and Evil|last=Lyman|first=Stanford|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=6–7}}</ref> | |||

| Sloth not only subverts the livelihood of the body, taking no care for its day-to-day provisions, but also slows down the mind, halting its attention to matters of great importance. Sloth hinders the man in his righteous undertakings and thus becomes a terrible source of human's undoing.<ref name=":4"/> | |||

| In his ''Purgatorio'' Dante portrayed the penance for acedia as running continuously at top speed. | |||

| Dante describes acedia as the ''failure to love God with all one's heart, all one's mind and all one's soul''; to him it was the ''middle sin'', the only one characterised by an absence or insufficiency of love. Some scholars{{who|date = July 2011}} have said that the ultimate form of acedia was despair which leads to suicide. | |||

| === Wrath === | === Wrath === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Wrath}} | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| Wrath can be defined as uncontrolled feelings of ], ], and even ]. Wrath often reveals itself in the wish to seek vengeance.<ref name="Landau-2010">{{Cite book|title=The Seven deadly Sins: A companion|last=Landau|first=Ronnie|isbn=978-1-4457-3227-5|date=30 October 2010|publisher=Lulu.com }}</ref> | |||

| {{Quote|text="People who fly into a rage always make a bad landing."|sign=]|source=}} | |||

| According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the neutral act of anger becomes the sin of wrath when it's directed against an innocent person, when it's unduly strong or long-lasting, or when it desires excessive punishment. "If anger reaches the point of a deliberate desire to kill or seriously wound a neighbor, it is gravely against charity; it is a mortal sin." (CCC 2302) Hatred is the sin of desiring that someone else may suffer misfortune or evil, and is a mortal sin when one desires grave harm. (CCC 2302-03) | |||

| According to the '']'', the neutral act of anger becomes the sin of wrath when it is directed against an innocent person, when it is unduly strong or long-lasting, or when it desires excessive punishment. "If anger reaches the point of a deliberate desire to kill or seriously wound a neighbor, it is gravely against charity; it is a mortal sin". Hatred is the sin of desiring that someone else may suffer misfortune or evil and is a mortal sin when one desires grave harm.<ref>{{CCC|pp=2302|pp_range=2302-3}}</ref> | |||

| People feel angry when they sense that they or someone they care about has been offended, when they are certain about the nature and cause of the angering event, when they are certain someone else is responsible, and when they feel they can still influence the situation or ] with it.<ref name="Anger pg 290">International Handbook of Anger. p. 290</ref> | |||

| People feel angry when they sense that they or someone they care about has been offended, when they are certain about the nature and cause of the angering event, when they are certain someone else is responsible, and when they feel that they can still influence the situation or ] with it.<ref name="Anger pg 290">International Handbook of Anger. p. 290</ref> | |||

| ] described vengeance as "love of ] perverted to revenge and ]".<ref name=":1"/> | |||

| Henry Edward Manning considers that "angry people are slaves to themselves".<ref name="Manning"/> | |||

| === Envy === | === Envy === | ||

| {{Main|Envy}}Envy is characterized by an insatiable desire like greed and lust. It can be described as a sad or resentful covetousness towards the traits or possessions of someone else. It comes from ]<ref name="books.google.com">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A7Cf9Bt1DWsC |title=Summa Theologica, Volume 3 (Part II, Second Section) |last=Aquinas |first=Thomas |author-link=St Thomas Aquinas |date=1 January 2013 |publisher=Cosimo, Inc. |isbn=9781602065581 |language=en}}</ref> and severs a man from his neighbor.<ref name="Manning"/> | |||

| {{Main article|Envy}} | |||

| ], painting by Bartolomeo Manfredi, c. 1600]] | |||

| According to St. Thomas Aquinas, the struggle aroused by envy has three stages: during the first stage, the envious person attempts to lower another's reputation; in the middle stage, the envious person receives either "joy at another's misfortune" (if he succeeds in defaming the other person) or "grief at another's prosperity" (if he fails); and the third stage is hatred because "sorrow causes hatred".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/aquinas/summa/sum291.htm |title=Summa Theologica: Treatise on The Theological Virtues (QQ[1] – 46): Question. 36 – Of Envy (four articles) |publisher=Sacred-texts.com |access-date=2 January 2010}}</ref> | |||

| '''Envy''' (Latin, {{lang|la|invidia}}), like greed and lust, is characterized by an insatiable desire. It can be described as a sad or resentful covetousness towards the traits or possessions of someone else. It arises from ],<ref name="books.google.com">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A7Cf9Bt1DWsC|title=Summa Theologica, Volume 3 (Part II, Second Section)|last=Aquinas|first=St Thomas|date=2013-01-01|publisher=Cosimo, Inc.|isbn=9781602065581|language=en}}</ref> and severs a man from his neighbor.<ref name=":32"/> | |||

| ] said that envy was one of the most potent causes of unhappiness, bringing sorrow to committers of envy, while giving them the urge to inflict pain upon others.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Conquest of Happiness |url=https://archive.org/details/conquestofhappin0000russ |url-access=registration |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |author-link=Bertrand Russell |publisher=] |year=1930 |location=] |page=86}}</ref> | |||

| Malicious envy is similar to jealousy in that they both feel discontent towards someone's traits, status, abilities, or rewards. A difference is that the envious also desire the entity and covet it. Envy can be directly related to the ], specifically, "Neither shall you covet... anything that belongs to your neighbour" - a statement that may also be related to ]. Dante defined envy as "a desire to deprive other men of theirs". In Dante's Purgatory, the punishment for the envious is to have their eyes sewn shut with wire because they gained sinful pleasure from seeing others brought low. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, the struggle aroused by envy has three stages: during the first stage, the envious person attempts to lower another's reputation; in the middle stage, the envious person receives either "joy at another's misfortune" (if he succeeds in defaming the other person) or "grief at another's prosperity" (if he fails); the third stage is hatred because "sorrow causes hatred" .<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/aquinas/summa/sum291.htm|title=Summa Theologica: Treatise on The Theological Virtues (QQ[1] – 46): Question. 36 – Of Envy (four articles)|publisher=Sacred-texts.com|date=|accessdate=January 2, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Envy is said to be the motivation behind ] murdering his brother, ], as Cain envied Abel because God favored Abel's sacrifice over Cain's. | |||

| ] said that envy was one of the most potent causes of unhappiness,<ref>{{cite book|title=The Conquest of Happiness|last=Russell|first=Bertrand|publisher=]|year=1930|location=]|page=<!-- insert page number -->}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=March 2017}} bringing sorrow to committers of envy whilst giving them the urge to inflict pain upon others. | |||

| In accordance with the most widely accepted views, only pride weighs down the soul more than envy among the capital sins. Just like pride, envy has been associated directly with the devil, for Wisdom 2:24 states:" the envy of the devil brought death to the world,".<ref name="books.google.com"/>{{clear}} | |||

| === Pride === | === Pride === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Pride}} | ||

| ]], also known as ] (from ] {{wikt-lang|grc|ὕβρις}}) or futility, is considered the original and worst of the seven deadly sins on almost every list, the most demonic.<ref name="Climacus 62–63">{{Cite book |last=Climacus |first=John |author-link=John Cliamcus |title=The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Translation by Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell |pages=62–63}}</ref> It is also thought to be the source of the other capital sins. Pride is the opposite of ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Humility vs Pride And Why The Difference Should Matter To You {{!}} Jeremie Kubicek |url=https://jeremiekubicek.com/humility-vs-pride/ |access-date=2 March 2018 |website=jeremiekubicek.com |language=en-US |archive-date=18 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180618175743/https://jeremiekubicek.com/humility-vs-pride/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Acquaviva |first=Gary J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qAtNAPteVk0C&q=Pride+is+generally+associated+with+an+absence+of+humility&pg=PA31 |title=Values, Violence and Our Future |date=2000 |publisher=Rodopi |isbn=9042005599 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| {{overquotation|section|date=May 2016}} | |||

| ] was, for Dante, an example of ''pride''. Painting by ]|240x240px]] | |||

| ''']''' (Latin, {{lang|la|superbia}}) is considered, on almost every list, the original and most serious of the seven deadly sins: the perversion of the faculties that make humans more like God—dignity and holiness. It is also thought to be the source of the other capital sins. Also known as ''']''' (from ] {{lang|grc|]}}), or '''futility''', it is identified as dangerously corrupt selfishness, the putting of one's own desires, urges, wants, and whims before the welfare of people. | |||

| ] writes in '']'' that pride is the "anti-God" state, the position in which the ego and the self are directly opposed to God: "Unchastity, anger, greed, drunkenness and all that, are mere fleabites in comparison: it was through Pride that Lucifer became wicked: Pride leads to every other vice: it is the complete anti-God state of mind."<ref>Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis, {{ISBN|978-0-06-065292-0}}</ref> Pride is understood to sever the spirit from God, as well as His life-and-grace-giving Presence.<ref name="Manning"/> | |||

| In even more destructive cases, it is irrationally believing that one is essentially and necessarily better, superior, or more important than others, failing to acknowledge the accomplishments of others, and excessive admiration of the personal image or self (especially forgetting one's own lack of divinity, and refusing to acknowledge one's own limits, faults, or wrongs as a human being). | |||

| One can be prideful for different reasons. Author ] states that "spiritual pride is the worst kind of pride, if not worst snare of the devil. The heart is particularly deceitful on this one thing."<ref name="Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers-1895">{{Cite book|title=Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers|year=1895|pages=485}}</ref> ] said: "remember that pride is the worst viper that is in the heart, the greatest disturber of the soul's peace and sweet communion with Christ; it was the first sin that ever was and lies lowest in the foundation of Lucifer's whole building and is the most difficultly rooted out and is the most hidden, secret and deceitful of all lusts and often creeps in, insensibly, into the midst of religion and sometimes under the disguise of humility."<ref>{{Cite book |title=To Deborah Hatheway, Letters and Personal Writings (Works of Jonathan Edwards Online Vol. 16) |last=Claghorn |first=George}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quote|text=What the weak head with strongest bias rules, Is pride, the never-failing vice of fools.|sign=]|source=], line 203.}} | |||

| The modern use of pride may be summed up in the ], "Pride goeth before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall" (abbreviated "Pride goeth before a fall", ] 16:18). The "pride that blinds" causes foolish actions against common sense.<ref name="Hollow-2014">{{cite journal |url=https://www.academia.edu/6081830 |title=The 1920 Farrow's Bank Failure: A Case of Managerial Hubris |journal=] |volume=20 |issue=2|pages=164–178 |publisher=] |access-date=1 October 2014 |last1=Hollow |first1=Matthew |doi=10.1108/JMH-11-2012-0071 |year=2014|issn = 1751-1348 }}</ref> In political analysis, "hubris" is often used to describe how leaders with great power over many years become more and more irrationally self-confident and contemptuous of advice, leading them to act impulsively.<ref name="Hollow-2014" /> | |||

| As pride has been labelled the father of all sins, it has been deemed the devil's most prominent trait. ] writes, in '']'', that pride is the "anti-God" state, the position in which the ego and the self are directly opposed to God: "Unchastity, anger, greed, drunkenness, and all that, are mere fleabites in comparison: it was through Pride that the devil became the devil: Pride leads to every other vice: it is the complete anti-God state of mind."<ref>Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis, {{ISBN|978-0-06-065292-0}}</ref> Pride is understood to sever the spirit from God, as well as His life-and-grace-giving Presence.<ref name=":32"/> | |||

| One can be prideful for different reasons. Author ] states that "piritual pride is the worst kind of pride, if not worst snare of the devil. The heart is particularly deceitful on this one thing."<ref name=":3">{{Cite book|title=Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers|last=|first=|publisher=|year=1895|isbn=|location=|pages=485}}</ref> ] said "emember that pride is the worst viper that is in the heart, the greatest disturber of the soul's peace and sweet communion with Christ; it was the first sin that ever was, and lies lowest in the foundation of Satan's whole building, and is the most difficultly rooted out, and is the most hidden, secret and deceitful of all lusts, and often creeps in, insensibly, into the midst of religion and sometimes under the disguise of humility."<ref>{{Cite book|title=To Deborah Hatheway, Letters and Personal Writings (Works of Jonathan Edwards Online Vol. 16)|last=Claghorn|first=George|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=}}</ref> | |||

| In Ancient Athens, hubris was considered one of the greatest crimes and was used to refer to insolent contempt that can cause one to use violence to shame the victim. This sense of hubris could also characterize rape.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/topic/hubris|title=hubris - Definition & Examples|publisher=}}</ref> ] defined hubris as shaming the victim, not because of anything that happened to the committer or might happen to the committer, but merely for the committer's own gratification.<ref name="Rhetoric">{{cite book |title=Rhetoric|author=Aristotle|page=1378b|url=http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.html}}</ref><ref name="law">{{cite book|last=Cohen|first=David|title=Law, Violence, and Community in Classical Athens|page=145|publisher=]|year=1995|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SJ9GjorvJGkC&pg=PA145|isbn=0521388376|accessdate=March 6, 2016}}</ref><ref name="eros">{{cite book|last=Ludwig|first=Paul W.|title=Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory|page=178|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2002|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TvqTEy-til8C&pg=PA172|isbn=1139434179|accessdate=March 6, 2016}}</ref> The word's connotation changed somewhat over time, with some additional emphasis towards a gross over-estimation of one's abilities. | |||

| The term has been used to analyse and make sense of the actions of contemporary heads of government by Ian Kershaw (1998), Peter Beinart (2010) and in a much more physiological manner by David Owen (2012). In this context the term has been used to describe how certain leaders, when put to positions of immense power, seem to become irrationally self-confident in their own abilities, increasingly reluctant to listen to the advice of others and progressively more impulsive in their actions.<ref name=":6"/> | |||

| Dante's definition of pride was "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbour". | |||

| Pride is associated with more intra-individual negative outcomes and is commonly related to expressions of aggression and hostility (Tangney, 1999). | |||

| As one might expect, pride is not always associated with high ] but with highly fluctuating or variable self-esteem. Excessive feelings of pride have a tendency to create conflict and sometimes terminating close relationships, which has led it to be understood as one of the few emotions with no clear positive or adaptive functions (Rhodwalt, et al.).{{Citation needed|date=June 2016}} | |||

| Pride is generally associated with an absence of ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://jeremiekubicek.com/humility-vs-pride/|title=Humility vs Pride And Why The Difference Should Matter To You {{!}} Jeremie Kubicek|website=jeremiekubicek.com|language=en-US|access-date=2018-03-02}}</ref>.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.in/books?id=qAtNAPteVk0C&pg=PA31&lpg=PA31&dq=Pride+is+generally+associated+with+an+absence+of+humility&source=bl&ots=NvXm9JG5Ns&sig=VrvLZ0pcmQZzLwhCMIUURKInFCM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjNnZ3_zJXZAhVBLo8KHUlcAAoQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=Pride%20is%20generally%20associated%20with%20an%20absence%20of%20humility&f=false|title=Values, Violence, and Our Future|last=Acquaviva|first=Gary J.|date=2000|publisher=Rodopi|isbn=9042005599|language=en}}</ref>{{Citation needed|date=June 2016}} It may also be associated with a lack of knowledge. ] states that "By ignorance is pride increased; They most assume who know the least."<ref name=":3"/> | |||

| In accordance with the ]'s author's wording, the heart of a proud man is "like a partridge in its cage acting as a decoy; like a spy he watches for your weaknesses. He changes good things into evil, he lays his traps. Just as a spark sets coals on fire, the wicked man prepares his snares in order to draw blood. Beware of the wicked man for he is planning evil. He might dishonor you forever." In another chapter, he says that "the acquisitive man is not content with what he has, wicked injustice shrivels the heart." | |||

| ] said "In reality there is, perhaps no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as ''pride''. Disguise it, struggle with it, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history. For even if I could conceive that I had completely overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility."<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Autobiography|last=Franklin|first=Benjamin|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=}}</ref> ] states that "There is no passion that steals into the heart more imperceptibly and covers itself under more disguises than pride."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers|last=|first=|publisher=|year=1895|isbn=|location=|pages=484}}</ref> | |||

| The proverb "pride goeth (goes) before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall" (from the biblical ], 16:18)(or pride goeth before the fall) is thought to sum up the modern use of pride. Pride is also referred to as "pride that blinds," as it often causes a committer of pride to act in foolish ways that belie common sense.<ref name=":6">{{cite web|url=https://www.academia.edu/6081830/The_1920_Farrows_Bank_Failure_A_Case_of_Managerial_Hubris|title=The 1920 Farrow's Bank Failure: A Case of Managerial Hubris|publisher=Durham University|deadurl=no|accessdate=October 1, 2014}}</ref> In other words, the modern definition may be thought of as, "that pride that goes just before the fall." In his two-volume biography of ], historian ] uses both 'hubris' and 'nemesis' as titles. The first volume, ''Hubris'',<ref>{{Cite book|title=Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris|last=Kershaw|first=Ian|publisher=]|year=1998|isbn=978-0-393-04671-7|location=New York|oclc=50149322|authorlink=Ian Kershaw}}</ref> describes Hitler's early life and rise to political power. The second, ''Nemesis'',<ref>{{cite book|title=Hitler 1936–1945: Nemesis|last=Kershaw|first=Ian|publisher=]|year=2000|isbn=978-0-393-04994-7|location=New York|oclc=45234118}}</ref> gives details of Hitler's role in the ], and concludes with his fall and suicide in 1945. | |||

| Much of the 10th and part of 11th chapter of the ] discusses and advises about pride, hubris, and who is rationally worthy of honor. It goes: | |||

| {{Quote|text="Do not store up resentment against your neighbor, no matter what his offence; do nothing in a fit of anger. Pride is odious to both God and man; injustice is abhorrent to both of them. Sovereignty is forced from one nation to another because of injustice, violence, and wealth. How can there be such pride in someone who is nothing but dust and ashes? Even while he is living, man's bowels are full of rottenness. Look: the illness lasts while the doctor makes light of it; and one who is king today will die tomorrow. Once a man is dead, grubs, insects, and worms are his lot.The beginning of man's pride is to separate himself from the Lord and to rebel against his Creator. The beginning of pride is sin. Whoever perseveres in sinning opens the floodgates to everything that is evil. For this the Lord has inflicted dire punishment on sinners; he has reduced them to nothing. The Lord has overturned the thrones of princes and set up the meek in their place. The Lord has torn up the proud by their roots and has planted the humble in their place. The Lord has overturned the land of ] and totally destroyed them. He has devastated several of them, destroyed them and removed all remembrance of them from the face of the earth. Pride was not created for man, nor violent anger for those born of woman. Which race is worthy of honor? The human race. Which race is worthy of honor? Those who are good. Which race is despicable? The human race. Which race is despicable? Those who break the commandments. The leader is worthy of respect in the midst of his brethren, but he has respect for those who are good. Whether, they be rich, honored or poor, their pride should be in being good. It is not right to despise the poor man who keeps the law; it is not fitting to honor the sinful man. The leader, the judge, and the powerful man are worthy of honor, but no one is greater than the man who is good. A prudent slave will have free men as servants, and the sensible man will not complain. Do not feel proud when you accomplished your work; do not put on airs when times are difficult for you. Of greater worth is the man who works and lives in abundance than the one who shows off and yet has nothing to live on. My son, have a modest appreciation of yourself, estimate yourself at your true value. Who will defend the man who takes his own life? Who will respect the man who despises himself? The poor man will be honored for his wisdom and the rich man, for his riches. Honored when poor-how much more honored when rich! Dishonored when rich-how much more dishonored when poor! The poor man who is intelligent carries his head high and sits among the great. Do not praise a man because he is handsome and do not hold a man in contempt because of his appearance. The bee is one of the smallest winged insects but she excels in the exquisite sweetness of her honey. Do not be irrationally proud just because of the clothes you wear; do not be proud when people honor you. Do you know what the Lord is planning in a mysterious way? Many tyrants have been overthrown and someone unknown has received the crown. Many powerful men have been disgraced and famous men handed over to the power of others. Do not reprehend anyone unless you have been first fully informed, consider the case first and thereafter make your reproach. Do not reply before you have listened; do not meddle in the disputes of sinners. My child, do not undertake too many activities. If you keep adding to them, you will not be without reproach; if you run after them, you will not succeed nor will you ever be free, although you try to escape."|sign=|source=],10:6–31 and 11:1–10}} | |||

| Jacob Bidermann's ] ], '']'', pride is the deadliest of all the sins and leads directly to the damnation of the titulary famed Parisian doctor. In Dante's ''Divine Comedy'', the penitents are burdened with stone slabs on their necks to keep their heads bowed. | |||

| == Historical sins == | == Historical sins == | ||

| === Acedia === | === Acedia === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Acedia}} | ||

| ], ]]] | ], ]]] | ||

| Acedia is the neglect to take care of something that one should do. It is translated to ] listlessness; depression without joy. It is related to ]; ''acedia'' describes the behaviour and ''melancholy'' suggests the emotion producing it. In early Christian thought, the lack of joy was regarded as a willful refusal to enjoy the goodness of God. By contrast, apathy was considered a refusal to help others in times of need. | |||

| Acēdia is negative form of the Greek term κηδεία, which has a more restricted usage. |

Acēdia is the negative form of the Greek term {{lang|grc|κηδεία}} ({{transliteration|grc|Kēdeia}}), which has a more restricted usage. "Kēdeia" refers specifically to spousal love and respect for the dead.<ref>Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. Revised by Sir Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940.</ref> | ||

| Pope Gregory combined this with ''tristitia'' into sloth for his list. When ] described ''acedia'' in his interpretation of the list, he described it as an |

Pope Gregory combined this with ''tristitia'' into sloth for his list. When ] described ''acedia'' in his interpretation of the list, he described it as an "uneasiness of the mind", being a progenitor for lesser sins such as restlessness and instability.<ref>{{Citation |title=From Gent to Gentil: Jed Tewksbury and the Function of Literary Allusion in A Place to Come To |url=https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies/vol2/iss1/6/ |last1=McCarron |first1=Bill |last2=Knoke |first2=Paul |journal=Robert Penn Warren Studies |date=2002 |volume=2 |issue=1 <!-- |article-number=6 -->}}</ref> | ||

| Acedia is currently defined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church as spiritual sloth, |

Acedia is currently defined in the '']'' as spiritual sloth, believing spiritual tasks to be too difficult.<ref>{{CCC|pp=2733}}</ref> In the fourth century, Christian monks believed that acedia was primarily caused by a state of ] that caused spiritual detachment instead of laziness.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/desert-fathers-sins-acedia-sloth|title=Before Sloth Meant Laziness, It Was the Spiritual Sin of Acedia|date=14 July 2017|work=Atlas Obscura|access-date=27 November 2017|language=en}}</ref> | ||

| ] | |||

| === Vainglory === | === Vainglory === | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Vanity}} | ||

| Vainglory is unjustified boasting. Pope Gregory viewed it as a form of pride, so he folded ''vainglory'' into pride for his listing of sins.<ref name="DelCogliano-2014"/> According to Aquinas, it is the progenitor of ].<ref name="books.google.com"/> | |||

| The Latin term |

The Latin term {{lang|la|gloria}} roughly means ''boasting'', although its English cognate ''glory'' has come to have an exclusively positive meaning. Historically, the term ''vain'' roughly meant ''futile'' (a meaning retained in the modern expression "in vain"), but by the fourteenth century had come to have the strong ] undertones which it still retains today.<ref>''Oxford English dictionary''</ref> | ||

| == |

== Confession patterns == | ||

| {{Further|Confession (religion)}} | |||

| With ], historic Christian denominations such as the Catholic Church and Protestant Churches,<ref name="Young1893">{{cite book|last=Young|first=David|title=The Origin and History of Methodism in Wales and the Borders|accessdate=5 February 2017|year=1893|publisher=C.H. Kelly|language=English|page=14|quote=For nearly a hundred years after the Reformation, excepting in cathedrals, churches, and chapels, there were no Bibles in Wales. The first book printed in the Welsh language was published in 1546, by Sir John Price of The Priory, Becon, and contained a translation of the Psalms, the Gospels as appointed to be read in the churches, the Lord's Prayer, the Ten Commandments, a Calendar, and the Seven Virtues of the Church. Sir John was a layman, a sturdy Protestant, and a man of considerable influence and ability.}}</ref> including the ],<ref name="Spicer2016">{{cite book|last=Spicer|first=Andrew|title=Lutheran Churches in Early Modern Europe|date=5 December 2016|publisher=Taylor & Francis|language=English|isbn=9781351921169|page=478|quote=The Lutheran emblem of a rose was painted in a sequence on the ceiling, while a decoratively carved pulpit included the Christo-centric symbol of a vulnerating pelican. The interior changed to a degree in the 1690s when Philip Tideman produced a series of grisaille paintings depicted the Seven Virtues (which hang from the gallery behind the pulpit), as well as decorating the wing doors of the organ.}}</ref> recognize ], which correspond inversely to each of the seven deadly sins. | |||

| {|class="sortable wikitable" cellspacing="8" | |||

| According to a 2009 study by the Jesuit scholar ], the most common deadly sin confessed by men is lust and the most common deadly sin confessed by women is pride.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7897034.stm |title=Two sexes 'sin in different ways' |work=] |date=18 February 2009 |access-date=24 July 2010}}</ref> It was unclear whether these differences were due to the actual number of transgressions committed by each sex or whether differing views on what "counts" or should be confessed caused the observed pattern.<ref>{{cite web |author=Morning Edition |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=100906920 |title=True Confessions: Men And Women Sin Differently |publisher=] |date=20 February 2009 |access-date=24 July 2010}}</ref> | |||

| !Vice | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| !Latin | |||

| !Italian | |||

| == See also == | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Div col}} | |||

| |''Luxuria'' | |||

| |"Lussuria" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Castitas'' | |||

| |"Castità" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Gula'' | |||

| |"Gola" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Moderatio'' | |||

| |"Temperanza" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Avaritia'' | |||

| |"Avarizia" | |||

| |] (or, sometimes, ]) | |||

| |''Caritas'' (''Liberalitas'') | |||

| |"Generosità" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Acedia'' | |||

| |"Accidia" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Industria'' | |||

| |"Diligenza" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Ira'' | |||

| |"Ira" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Patientia'' | |||

| |"Pazienza" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Invidia'' | |||

| |"Invidia" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Gratia'' | |||

| |"Gratitudine" | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Superbia'' | |||

| |"Superbia" | |||

| |] | |||

| |''Humilitas'' | |||

| |"Umiltà" | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| == Confession Patterns == | |||

| Confession is the act of admitting the commission of a sin to a priest, who in turn will forgive the person in the name (in the person) of Christ, give a penance to (partially) make up for the offense, and advise the person on what he or she should do afterwards. | |||

| According to a 2009 study by Fr Roberto Busa, a Jesuit scholar{{who|date=February 2017}}, the most common deadly sin confessed by men is supposedly lust, and by women, pride.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7897034.stm|title=Two sexes 'sin in different ways'|publisher=BBC News|date=February 18, 2009|accessdate=July 24, 2010}}</ref> It was unclear whether these differences were due to the actual number of transgressions committed by each sex, or whether differing views on what "counts" or should be confessed caused the observed pattern.<ref>{{cite web|author=Morning Edition|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=100906920|title=True Confessions: Men And Women Sin Differently|publisher=Npr.org|date=February 20, 2009|accessdate=July 24, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| == In art == | |||

| === ] '']'' === | |||

| The second book of Dante's epic poem '']'' is structured around the seven deadly sins. The most serious sins, found at the lowest level, are the abuses of the most divine faculty. For Dante and other thinkers, a human's rational faculty makes humans more like God. Abusing that faculty with pride or envy weighs down the soul the most. Abusing one's passions with wrath or a lack of passion as with sloth also weighs down the soul but not as much as the abuse of one's rational faculty. Finally, abusing one's desires to have one's physical needs met via greed, gluttony, or lust abuses a faculty that humans share with animals. This is still an abuse that weighs down the soul, but it does not weigh it down like other abuses. Thus, the top levels of the Mountain of Purgatory have the top listed sins, while the lowest levels have the more serious sins of wrath, envy, and pride. | |||

| # {{lang|la|luxuria}} / Lust<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| |last=Godsall-Myers|first=Jean E.|authorlink=|title=Speaking in the medieval world|publisher=Brill|year=2003|location=|page=27|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Hgw0WSuUZn4C&pg=PA27|doi=|isbn=90-04-12955-3}} | |||

| </ref><ref>{{Cite book | |||

| |last=Katherine Ludwig|first=Jansen|authorlink=|title=The making of the Magdalen: preaching and popular devotion in the later Middle Ages|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=2001|location=|page=168|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tAxSQ7O4WogC&pg=PA194|isbn=0-691-08987-6}} | |||

| </ref><ref>{{Cite book | |||

| |last=Vossler|first=Karl|last2=Spingarn|first2=Joel Elias|title=Mediæval Culture: The religious, philosophic, and ethico-political background of the "Divine Comedy"|publisher=Constable & company|year=1929|location=University of Michigan|page=246|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=McIRAAAAMAAJ|doi=|isbn=}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| # {{lang|la|gula}} / Gluttony | |||

| # {{lang|la|avaritia}} / Greed | |||

| # {{lang|la|acedia}} / Sloth | |||

| # {{lang|la|ira}} / Wrath | |||

| # {{lang|la|invidia}} / Envy | |||

| # {{lang|la|superbia}} / Pride | |||

| === ]'s "]" === | |||

| The last tale of the ], the "Parson's Tale" is not a tale but a sermon that the parson gives against the seven deadly sins. This sermon brings together many common ideas and images about the seven deadly sins. This tale and Dante's work both show how the seven deadly sins were used for confessional purposes or as a way to identify, repent of, and find forgiveness for one's sins.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Canterbury Tales|url=https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/c/the-canterbury-tales/summary-and-analysis/the-parsons-prologue-and-tale|website=CliffsNotes|accessdate=30 June 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Dante's Inferno and Saint Augustine's Confessions|url=https://h2g2.com/entry/A1912169|website=h2g2|accessdate=30 June 2017}}</ref> | |||

| === ]'s Prints of the Seven Deadly Sins === | |||

| The Dutch artist created a series of prints showing each of the seven deadly sins. Each print features a central, labeled image that represents the sin. Around the figure are images that show the distortions, degenerations, and destructions caused by the sin.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Prints and Drawings|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art|date=2001-09-01|location=New York|isbn=9780300090147|editor-first=Nadine M.|editor-last=Orenstein}}</ref> Many of these images come from contemporary Dutch aphorisms.<ref>{{Cite book|edition=1st Edition / 1st Printing|title=Graphic Work of Peter Bruegel, the Elder: Reproducing 64 Engravings and a Woodcut After Designs By Peter Bruegel the Elder.|publisher=Dover Publications|date=1963-01-01|first=H. Arthur|last=Klein}}</ref> | |||

| === ]'s '']'' === | |||

| Spenser's work, which was meant to educate young people to embrace virtue and avoid vice, includes a colourful depiction of the House of Pride. Lucifera, the lady of the house, is accompanied by advisers who represent the other seven deadly sins.{{Citation needed|date=June 2016}} | |||

| === ] and ]'s '']'' === | |||

| This work satirized capitalism and its painful abuses as its central character, the victim of a split personality, travels to seven different cities in search of money for her family. In each city she encounters one of the seven deadly sins, but those sins ironically reverse one's expectations. When the character goes to Los Angeles, for example, she is outraged by injustice, but is told that wrath against capitalism is a sin that she must avoid.{{Citation needed|date=June 2016}} | |||

| === ]' ''The Seven Deadly Sins'' === | |||

| Between 1945 and 1949, the American painter Paul Cadmus created a series of vivid, powerful, and gruesome paintings of each of the seven deadly sins.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Paul Cadmus {{!}} The Seven Deadly Sins: Pride {{!}} The Metropolitan Museum of Art|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/486323|website=www.metmuseum.org|accessdate=2015-12-04}}</ref> | |||

| ==Revalorization== | |||

| ] maintains that ], especially through ], has surprisingly given valor to vices, causing society to regress into that of primitive ]: "covetousness has been rebranded as ], sloth is ], lust is ], anger is opening up your feelings, vanity is looking good because you're worth it and gluttony is the religion of ]s".<ref>F. Mount, ''Full Circle'' (2010) p. 302</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{Columns-list|colwidth=22em| | |||

| * ] in ] | * ] in ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| * ] in ] | |||

| * ] in ] | * ] in ] | ||

| * ] in ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] and ] in ] | * ] and ] in ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * '']'' |

* '']'' | ||

| * ] in ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] in ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Div col end}} | |||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| {{ |

{{reflist}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | == Further reading == | ||

| * ], '']'' | |||

| * Tucker, Shawn. ''The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook'', (Eugene, OR: Cascade Press, 2015) | |||

| * {{cite book |chapter=] |title=Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume XI |year=1885 |publisher=T. & T. Clark in Edinburgh |first=John |last=Cassian |author-link=John Cassian |translator-first=Philip |translator-last=Schaff}} | |||

| * Schumacher, Meinolf (2005): "Catalogues of Demons as Catalogues of Vices in Medieval German Literature: 'Des Teufels Netz' and the Alexander Romance by Ulrich von Etzenbach." In ''In the Garden of Evil: The Vices and Culture in the Middle Ages''. Edited by Richard Newhauser, pp. 277–290. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. | |||

| * {{cite book|chapter=]|title=Meditations On The Mysteries Of Our Holy Faith|year=1852|publisher=Richarson and Son|first=Lius|last=de la Puente|author-link=Luis de la Puente}} | |||

| * ''The Divine Comedy'' ("Inferno", "Purgatorio", and "]"), by Dante Alighieri | |||

| * {{ill|Schumacher, Meinolf|de|Meinolf Schumacher}} (2005): "Catalogues of Demons as Catalogues of Vices in Medieval German Literature: 'Des Teufels Netz' and the Alexander Romance by Ulrich von Etzenbach." In ''In the Garden of Evil: The Vices and Culture in the Middle Ages''. Edited by Richard Newhauser, pp. 277–290. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. | |||

| * '']'', by Thomas Aquinas | |||

| * ''The Concept of Sin'', by ] | * ''The Concept of Sin'', by ] | ||

| * ''The Traveller's Guide to Hell'', by Michael Pauls & Dana Facaros | * ''The Traveller's Guide to Hell'', by Michael Pauls & Dana Facaros | ||

| * ''Sacred Origins of Profound Things'', by Charles Panati | * ''Sacred Origins of Profound Things'', by ] | ||

| * '']'', by ] | * '']'', by ] | ||

| * '''', ] (7 vols.) | * '''', ] (7 vols.) | ||

| * Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung, ''Glittering Vices: A New Look at the Seven Deadly Sins and Their Remedies,'' (Grand Rapids: BrazosPress, 2009) | * ], ''Glittering Vices: A New Look at the Seven Deadly Sins and Their Remedies,'' (Grand Rapids: BrazosPress, 2009) | ||

| * Solomon Schimmel, ''The Seven Deadly Sins: Jewish, Christian |

* ], ''The Seven Deadly Sins: Jewish, Christian and Classical Reflections on Human Psychology,'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) | ||

| * {{cite book|chapter=]|title=A manual of moral theology for English-speaking countries|year=1925|publisher=Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd.|first=Thomas|last=Slater S.J.}} | |||

| * "]" by ] | |||

| * Tucker, Shawn. ''The Virtues and Vices in the Arts: A Sourcebook'', (Eugene, OR: Cascade Press, 2015) | |||

| == External links == | |||

| * {{YouTube|id=Beu-XQHH9xQ|title=''Se7en'' (Film) – Paradise Lost}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|The Seven Deadly Sins}} | {{Commons category|The Seven Deadly Sins}} | ||

| {{Wikiquote}}{{Seven Deadly Sins|state=expanded}} | |||

| * | |||

| * – in parish churches of England (online catalog, Anne Marshall, Open University) | |||

| * , {{ISBN|9781311073846}} | |||

| {{Seven Deadly Sins|state=expanded}} | |||

| {{Catholic virtue ethics}} | {{Catholic virtue ethics}} | ||