| Revision as of 15:43, 2 November 2006 edit72.159.246.99 (talk) →External links← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:21, 26 December 2024 edit undoChetvorno (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users65,374 edits →Physical characteristics: Added picture of gray arsenic | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_header | number=33 | symbol=As | name=arsenic | left=] | right=] | above=] | below=] | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| {{About|the chemical element|the poison commonly called "arsenic"|arsenic trioxide|other uses}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_series | ]s }} | |||

| {{Infobox arsenic}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_groupperiodblock | group=15 | period=4 | block=p }} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2020}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_appearance_img | As,33| metallic gray }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicmass_gpm | ]] }} | |||

| '''Arsenic''' is a ] with the ] '''As''' and the ] 33. It is a ] and one of the ], and therefore shares many properties with its ] neighbors ] and ]. Arsenic is a notoriously ]. It occurs naturally in many ], usually in combination with ] and metals, but also as a pure elemental ]. It has various ], but only the grey form, which has a metallic appearance, is important to industry. | |||

| {{Elementbox_econfig | []] 3d<sup>10</sup> 4s<sup>2</sup> 4p<sup>3</sup> }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_epershell | 2, 8, 18, 5 }} | |||

| The primary use of arsenic is in alloys of lead (for example, in ] and ]). Arsenic is a common n-type ] in ] electronic devices. It is also a component of the III–V ] ]. Arsenic and its compounds, especially the trioxide, are used in the production of ]s, treated wood products, ]s, and ]s. These applications are declining with the increasing recognition of the toxicity of arsenic and its compounds.<ref name="Ullmann">{{Ullmann|author = Grund, Sabina C. |author2 = Hanusch, Kunibert |author3 = Wolf, Hans Uwe |title = Arsenic and Arsenic Compounds|doi = 10.1002/14356007.a03_113.pub2}}</ref> | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_physicalprop | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_phase | ] }} | |||

| Arsenic has been known since ancient times to be poisonous to humans.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://sites.dartmouth.edu/toxmetal/arsenic/arsenic-a-murderous-history/ | title=Arsenic: A Murderous History | Dartmouth Toxic Metals }}</ref> However, a few species of bacteria are able to use arsenic compounds as respiratory ]s. Trace quantities of arsenic have been proposed to be an essential ] in rats, hamsters, goats, and chickens. Research has not been conducted to determine whether small amounts of arsenic may play a role in human metabolism.<ref name=ANut /><ref name=UEssent /> However, ] occurs in multicellular life if quantities are larger than needed. ] is a problem that affects millions of people across the world. | |||

| {{Elementbox_density_gpcm3nrt | 5.727 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_densityliq_gpcm3mp | 5.22 }} | |||

| The United States' ] states that all forms of arsenic are a serious risk to human health.<ref name="EPA1">{{cite web |url=https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.highlight/abstract/6015 |title=Biogeochemistry of Arsenic in Contaminated Soils of Superfund Sites |last1=Dibyendu |first1=Sarkar |last2=Datta |first2=Rupali |date=2007 |website=EPA |publisher=United States Environmental Protection Agency |access-date=25 February 2018 }}</ref> The United States' ] ranked arsenic number 1 in its 2001 prioritized list of ] substances at ] sites.<ref>{{cite web |last=Carelton |first=James |date=2007 |title=Final Report: Biogeochemistry of Arsenic in Contaminated Soils of Superfund Sites |url=https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.highlight/abstract/6015/report/F |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180728035900/https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncer_abstracts/index.cfm/fuseaction/display.highlight/abstract/6015/report/F |archive-date=28 July 2018 |access-date=25 February 2018 |publisher=United States Environmental Protection Agency}}</ref> Arsenic is classified as a Group-A ].<ref name="EPA1" /> | |||

| {{Elementbox_meltingpoint | k=1090 | c=817 | f=1503 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_boilingpoint | k=] 887 | c=614 | f=1137 }} | |||

| == Characteristics == | |||

| === Physical characteristics === | |||

| {{main|Allotropes of arsenic}} | |||

| ], ] and grey As]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The three most common arsenic ] are grey, yellow, and black arsenic, with grey being the most common.<ref name="Norman">{{cite book|title = Chemistry of Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth|first = Nicholas C.|last = Norman|publisher = Springer|date = 1998|isbn = 978-0-7514-0389-3|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=vVhpurkfeN4C|page = 50}}</ref> Grey arsenic (α-As, ] R{{overline|3}}m No. 166) adopts a double-layered structure consisting of many interlocked, ruffled, six-membered rings. Because of weak bonding between the layers, grey arsenic is brittle and has a relatively low ] of 3.5. Nearest and next-nearest neighbors form a distorted octahedral complex, with the three atoms in the same double-layer being slightly closer than the three atoms in the next.<ref name="Wiberg2001">{{cite book|last1 = Wiberg|first1 = Egon|last2 = Wiberg|first2 = Nils|last3 = Holleman|first3 = Arnold Frederick|title = Inorganic Chemistry|publisher = Academic Press|date = 2001|isbn = 978-0-12-352651-9}}</ref> This relatively close packing leads to a high density of 5.73 g/cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref name="Holl" /> Grey arsenic is a ], but becomes a ] with a ] of 1.2–1.4 eV if ].<ref>{{cite book|author=Madelung, Otfried |title=Semiconductors: data handbook|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v_8sMfNAcA4C&pg=PA410|date=2004|publisher=Birkhäuser|isbn=978-3-540-40488-0|pages=410–}}</ref> Grey arsenic is also the most stable form. | |||

| Yellow arsenic is soft and waxy, and somewhat similar to ] ({{chem2|P4}}).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Seidl |first1=Michael |last2=Balázs |first2=Gábor |last3=Scheer |first3=Manfred |title=The Chemistry of Yellow Arsenic |journal=Chemical Reviews |volume=119 |issue=14 |pages=8406–8434 |date=22 March 2019 |doi=10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00713|pmid=30900440 |s2cid=85448636 }}</ref> Both have four atoms arranged in a ] structure in which each atom is bound to each of the other three atoms by a single bond. This unstable allotrope, being molecular, is the most volatile, least dense, and most toxic. Solid yellow arsenic is produced by rapid cooling of arsenic vapor, {{chem2|As4}}. It is rapidly transformed into grey arsenic by light. The yellow form has a density of 1.97 g/cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref name="Holl" /> Black arsenic is similar in structure to ].<ref name="Holl" /><!--10.1002/jlac.18440490302 Ueber Allotropie bei einfachen Körpern, als eine der Ursachen der Isomerie bei ihren Verbindungen (pp. 247–264) | |||

| Jac. Berzelius Volume 49 Issue 3, Pages 247–366 (1844) Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie | |||

| 10.1002/jlac.18671440115 | |||

| 10.1002/jlac.19134000206 | |||

| 10.1002/zaac.19020320158 | |||

| 10.1002/zaac.18940060139 | |||

| 10.1002/cber.19080410197 | |||

| 10.1002/zaac.18940060139 | |||

| --> | |||

| Black arsenic can also be formed by cooling vapor at around 100–220 °C and by crystallization of amorphous arsenic in the presence of mercury vapors.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Antonatos|first1=Nikolas|last2=Luxa|first2=Jan|last3=Sturala|first3=Jiri|last4=Sofer|first4=Zdeněk|date=2020|title=Black arsenic: a new synthetic method by catalytic crystallization of arsenic glass|journal=Nanoscale|volume=12|issue=9|language=en|pages=5397–5401|doi=10.1039/C9NR09627B|pmid=31894222|s2cid=209544160}}</ref> It is glassy and brittle. Black arsenic is also a poor electrical conductor.<ref>. chemicool.com</ref> | |||

| Arsenic ] upon heating at ], converting directly to a gaseous form without an intervening liquid state at {{convert|887|K|C}}. The ] is at 3.63 MPa and {{convert|1090|K|C}}.<ref name="Holl" /><ref name="Gokcen1989" /> | |||

| === Isotopes === | |||

| {{Main|Isotopes of arsenic}} | |||

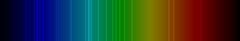

| Arsenic occurs in nature as one stable ], <sup>75</sup>As, and is therefore called a ].<ref name="NUBASE">{{NUBASE 2003}}</ref> As of 2024, at least 32 ]s have also been synthesized, ranging in ] from 64 to 95.<ref>{{NUBASE 2020}}</ref><ref name="shimizu2024">{{cite journal |last1=Shimizu |first1=Y. |last2=Kubo |first2=T. |last3=Sumikama |first3=T. |last4=Fukuda |first4=N. |last5=Takeda |first5=H. |last6=Suzuki |first6=H. |last7=Ahn |first7=D. S. |last8=Inabe |first8=N. |last9=Kusaka |first9=K. |last10=Ohtake |first10=M. |last11=Yanagisawa |first11=Y. |last12=Yoshida |first12=K. |last13=Ichikawa |first13=Y. |last14=Isobe |first14=T. |last15=Otsu |first15=H. |last16=Sato |first16=H. |last17=Sonoda |first17=T. |last18=Murai |first18=D. |last19=Iwasa |first19=N. |last20=Imai |first20=N. |last21=Hirayama |first21=Y. |last22=Jeong |first22=S. C. |last23=Kimura |first23=S. |last24=Miyatake |first24=H. |last25=Mukai |first25=M. |last26=Kim |first26=D. G. |last27=Kim |first27=E. |last28=Yagi |first28=A. |title=Production of new neutron-rich isotopes near the N = 60 isotones Ge 92 and As 93 by in-flight fission of a 345 MeV/nucleon U 238 beam |journal=Physical Review C |date=8 April 2024 |volume=109 |issue=4 |page=044313 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevC.109.044313}}</ref> The most stable of these is <sup>73</sup>As with a ] of 80.30 days. All other isotopes have half-lives of under one day, with the exception of <sup>71</sup>As (''t''<sub>1/2</sub>=65.30 hours), <sup>72</sup>As (''t''<sub>1/2</sub>=26.0 hours), <sup>74</sup>As (''t''<sub>1/2</sub>=17.77 days), <sup>76</sup>As (''t''<sub>1/2</sub>=26.26 hours), and <sup>77</sup>As (''t''<sub>1/2</sub>=38.83 hours). Isotopes that are lighter than the stable <sup>75</sup>As tend to decay by ], and those that are heavier tend to decay by ], with some exceptions. | |||

| At least 10 ]s have been described, ranging in atomic mass from 66 to 84. The most stable of arsenic's isomers is <sup>68m</sup>As with a half-life of 111 seconds.<ref name="NUBASE" /> | |||

| === Chemistry === | |||

| Arsenic has a similar ] and ] to its lighter ] ] phosphorus and therefore readily forms ] molecules with most of the ]. Though stable in dry air, arsenic forms a golden-bronze ] upon exposure to humidity which eventually becomes a black surface layer.<ref name="Greenwood552">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 552–4</ref> When heated in air, arsenic ] to ]; the fumes from this reaction have an odor resembling garlic. This odor can be detected on striking ] minerals such as ] with a hammer.<ref name="Gokcen1989" /> It burns in oxygen to form arsenic trioxide and ], which have the same structure as the more well-known phosphorus compounds, and in fluorine to give ].<ref name="Greenwood552" /> Arsenic makes ] with concentrated ], ] with dilute nitric acid, and ] with concentrated ]; however, it does not react with water, alkalis, or non-oxidising acids.<ref>{{cite EB1911|wstitle=Arsenic |volume=2 |pages=651–654}}</ref> Arsenic reacts with metals to form ]s, though these are not ionic compounds containing the As<sup>3−</sup> ion as the formation of such an anion would be highly endothermic and even the group 1 arsenides have properties of ] compounds.<ref name="Greenwood552" /> Like ], ], and ], which like arsenic ], arsenic is much less stable in the +5 ] than its vertical neighbors phosphorus and ], and hence arsenic pentoxide and arsenic acid are potent ].<ref name="Greenwood552" /> | |||

| == Compounds == | |||

| {{Category see also|Arsenic compounds}} | |||

| Compounds of arsenic resemble, in some respects, those of ], which occupies the same ] (column) of the ]. The most common ]s for arsenic are: −3 in the ]s, which are alloy-like intermetallic compounds, +3 in the ]s, and +5 in the ] and most organoarsenic compounds. Arsenic also bonds readily to itself as seen in the square {{chem2|As4(3-)}} ions in the mineral ].<ref>{{cite book |doi = 10.1016/S0080-8784(01)80151-4 |title = Recent Trends in Thermoelectric Materials Research I: Skutterudites: Prospective novel thermoelectrics |date = 2001 |last1 = Uher |first1 = Ctirad |isbn = 978-0-12-752178-7 |volume = 69 |pages = 139–253| series = Semiconductors and Semimetals |chapter = Chapter 5 Skutterudites: Prospective novel thermoelectrics }}</ref> In the +3 ], arsenic is typically pyramidal owing to the influence of the ] of ]s.<ref name="Norman" /><!--page 30--> | |||

| === Inorganic compounds === | |||

| One of the simplest arsenic compounds is the trihydride, the highly toxic, flammable, ] ] (AsH<sub>3</sub>). This compound is generally regarded as stable, since at room temperature it decomposes only slowly. At temperatures of 250–300 °C decomposition to arsenic and hydrogen is rapid.<ref name="Greenwood557">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 557–558</ref> Several factors, such as ], presence of light and certain ]s (namely aluminium) facilitate the rate of decomposition.<ref name="INRS">{{cite web |website=Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité |title=Fiche toxicologique No. 53: Trihydrure d'arsenic |year = 2000 |url = http://www.inrs.fr/inrs-pub/inrs01.nsf/IntranetObject-accesParReference/FT%2053/$File/ft53.pdf |access-date = 2006-09-06 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20061126045357/http://www.inrs.fr/inrs-pub/inrs01.nsf/IntranetObject-accesParReference/FT%2053/$FILE/ft53.pdf |archive-date = 26 November 2006 |language=fr}}</ref> It oxidises readily in air to form arsenic trioxide and water, and analogous reactions take place with ] and ] instead of ].<ref name="Greenwood557" /> | |||

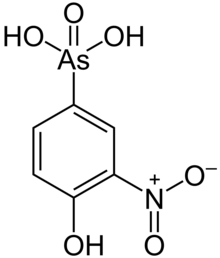

| Arsenic forms colorless, odorless, crystalline ]s ] ("]") and ] which are ] and readily soluble in water to form acidic solutions. ] is a weak acid and its salts, known as ]s,<ref name="Greenwood572" /> are a major source of ] in regions with high levels of naturally-occurring arsenic minerals.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Smedley |first1=P.L |last2=Kinniburgh |first2=D.G |title=A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters |journal=Applied Geochemistry |date=May 2002 |volume=17 |issue=5 |pages=517–568 |doi=10.1016/S0883-2927(02)00018-5 |bibcode=2002ApGC...17..517S |url=http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/12311/1/Abstract.pdf }}</ref> Synthetic arsenates include ] (cupric hydrogen arsenate, acidic copper arsenate), ], and ]. These three have been used as agricultural ]s and ]s. | |||

| The ] steps between the arsenate and arsenic acid are similar to those between ] and ]. Unlike ], ] is genuinely tribasic, with the formula As(OH)<sub>3</sub>.<ref name="Greenwood572">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 572–578</ref> | |||

| A broad variety of sulfur compounds of arsenic are known. Orpiment (]) and realgar (]) are somewhat abundant and were formerly used as painting pigments. In As<sub>4</sub>S<sub>10</sub>, arsenic has a formal oxidation state of +2 in As<sub>4</sub>S<sub>4</sub> which features As-As bonds so that the total covalency of As is still 3.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webelements.com/webelements/compounds/text/As/As4S4-12279902.html|title=Arsenic: arsenic(II) sulfide compound data|access-date=2007-12-10|publisher=WebElements.com| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071211100733/http://www.webelements.com/webelements/compounds/text/As/As4S4-12279902.html| archive-date= 11 December 2007|url-status = live}}</ref> Both orpiment and realgar, as well as As<sub>4</sub>S<sub>3</sub>, have selenium analogs; the analogous As<sub>2</sub>Te<sub>3</sub> is known as the mineral ],<ref> | |||

| {{cite web |url=https://www.mindat.org/min-47039.html |title=Kalgoorlieite |date=1993–2017 |website=Mindat |publisher=Hudson Institute of Mineralogy |access-date=2 September 2017}}</ref> and the anion As<sub>2</sub>Te<sup>−</sup> is known as a ligand in ] complexes.<ref name="Greenwood578">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 578–583</ref> | |||

| All trihalides of arsenic(III) are well known except the astatide, which is unknown. ] (AsF<sub>5</sub>) is the only important pentahalide, reflecting the lower stability of the +5 oxidation state; even so, it is a very strong fluorinating and oxidizing agent. (The ] is stable only below −50 °C, at which temperature it decomposes to the trichloride, releasing chlorine gas.<ref name="Holl" />) | |||

| ==== Alloys ==== | |||

| Arsenic is used as the group 5 element in the ]s ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.019 |title = Toxicity of indium arsenide, gallium arsenide, and aluminium gallium arsenide |date = 2004 |last1 = Tanaka |first1 = A. |journal = Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology |volume = 198 |issue = 3 |pages = 405–411 |pmid = 15276420|bibcode = 2004ToxAP.198..405T }}</ref> The valence electron count of GaAs is the same as a pair of Si atoms, but the ] is completely different which results in distinct bulk properties.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pkuuvlNjRtsC&pg=PA1 |title=Light Emitting Silicon for Microphotonics |isbn = 978-3-540-40233-6|last1=Ossicini |first1=Stefano |last2=Pavesi |first2=Lorenzo |last3=Priolo |first3=Francesco |year=2003 |publisher=Springer |access-date=2013-09-27}}</ref> Other arsenic alloys include the II-V semiconductor ].<ref>{{cite book |doi = 10.1109/SMELEC.1998.781173 |date = 1998 |last1 = Din |first1 = M. B. |last2 = Gould |first2 = R. D. |title = ICSE'98. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Semiconductor Electronics. Proceedings (Cat. No. 98EX187) |chapter = High field conduction mechanism of the evaporated cadmium arsenide thin films |isbn = 978-0-7803-4971-1 |pages = 168–174|s2cid = 110904915 }}</ref> | |||

| === Organoarsenic compounds === | |||

| {{Main|Organoarsenic chemistry}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| A large variety of organoarsenic compounds are known. Several were developed as ] during World War I, including ] such as ] and vomiting agents such as ].<ref name="Ellison2007">{{cite book|last=Ellison|first=Hank D.|title=Handbook of chemical and biological warfare agents|date=2007|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-8493-1434-6}}</ref><ref name="Girard2010">{{cite book|last=Girard|first=James|title=Principles of Environmental Chemistry|date=2010|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|isbn=978-0-7637-5939-1}}</ref><ref name="Somani2001">{{cite book|last=Somani|first=Satu M.|title=Chemical warfare agents: toxicity at low levels|date=2001|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-0-8493-0872-7}}</ref> ], which is of historic and practical interest, arises from the ] of arsenic trioxide, a reaction that has no analogy in phosphorus chemistry. ] was the first organometallic compound known (even though arsenic is not a true metal) and was named from the Greek ''κακωδία'' "stink" for its offensive, garlic-like odor; it is very toxic.<ref name="Greenwood584">Greenwood, p. 584</ref> | |||

| {{clear left}} | |||

| == Occurrence and production == | |||

| {{See also|:Category:Arsenide minerals|l1=Arsenide minerals|:Category:Arsenate minerals|l2=Arsenate minerals}} | |||

| ], France]] | |||

| Arsenic is the 53rd most abundant element in the ], comprising about 1.5 ] (0.00015%).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Emsley |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dGZaDwAAQBAJ&dq=%2253rd+most+abundant+element%22&pg=PA52 |title=Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements |date=2011-08-25 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-257046-8 |language=en}}</ref> Typical background concentrations of arsenic do not exceed 3 ng/m<sup>3</sup> in the atmosphere; 100 mg/kg in soil; 400 μg/kg in vegetation; 10 μg/L in freshwater and 1.5 μg/L in seawater.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Rieuwerts|first=John |title=The Elements of Environmental Pollution|date=2015|publisher=Earthscan Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-85919-6|location=London and New York|page=145 |oclc=886492996}}</ref> Arsenic is the 22nd most abundant element in seawater<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Papry |first1=Rimana Islam |last2=Omori |first2=Yoshiki |last3=Fujisawa |first3=Shogo |last4=Al Mamun |first4=M. Abdullah |last5=Miah |first5=Sohag |last6=Mashio |first6=Asami S. |last7=Maki |first7=Teruya |last8=Hasegawa |first8=Hiroshi |date=2020-05-01 |title=Arsenic biotransformation potential of marine phytoplankton under a salinity gradient |journal=Algal Research |volume=47 |pages=101842 |doi=10.1016/j.algal.2020.101842 |bibcode=2020AlgRe..4701842P }}</ref> and ranks 41st in abundance in the universe.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Helmenstine |first=Anne |date=2022-06-28 |title=Composition of the Universe - Element Abundance |url=https://sciencenotes.org/composition-of-the-universe-element-abundance/ |access-date=2024-06-13 |website=Science Notes and Projects |language=en-US}}</ref>{{Unreliable source?|date=December 2024}} | |||

| Minerals with the formula MAsS and MAs<sub>2</sub> (M = ], ], ]) are the dominant commercial sources of arsenic, together with ] (an arsenic sulfide mineral) and native (elemental) arsenic. An illustrative mineral is ]<!--, also unofficially called mispickel,<ref>{{cite journal|journal = Geology Today|volume = 18|issue = 2|pages = 72–75|title = Minerals explained 35: Arsenopyrite|first =R. J.|last = King|year = 2002|doi = 10.1046/j.1365-2451.2002.t01-1-00006.x}}</ref>--> (]As]), which is structurally related to ]. Many minor As-containing minerals are known. Arsenic also occurs in various organic forms in the environment.<ref name="geosphere">{{cite journal|journal = The Science of the Total Environment|volume = 249|date = 2000|pages = 297–312| doi = 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00524-0|title = Arsenic in the geosphere – a review|first = Jörg|last = Matschullat|pmid = 10813460|issue = 1–3|bibcode = 2000ScTEn.249..297M}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 2014, China was the top producer of white arsenic with almost 70% world share, followed by Morocco, Russia, and Belgium, according to the ] and the ].<ref name="USGSCS2016" /> Most arsenic refinement operations in the US and Europe have closed over environmental concerns. Arsenic is found in the smelter dust from copper, gold, and lead smelters, and is recovered primarily from copper refinement dust.<ref name="USGSYB2007" /> | |||

| On ] arsenopyrite in air, arsenic sublimes as arsenic(III) oxide leaving iron oxides,<ref name="geosphere" /> while roasting without air results in the production of gray arsenic. Further purification from sulfur and other chalcogens is achieved by ] in vacuum, in a hydrogen atmosphere, or by distillation from molten lead-arsenic mixture.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Separation of Sulfur, Selenium, and Tellurium from Arsenic|journal = Journal of the Electrochemical Society|volume = 107|issue = 12|pages = 982–985|date = 1960|first1 = J. M.|last1 = Whelan|doi = 10.1149/1.2427585|last2 = Struthers|first2 = J. D.|last3 = Ditzenberger|first3 = J. A.|doi-access = free}}</ref><!-- 10.1023/A:1012370808738--> | |||

| {|class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Rank !! Country !! 2014 ] Production<ref name="USGSCS2016">{{cite web|url =http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/arsenic/mcs-2016-arsen.pdf|first = Daniel L.|last = Edelstein |publisher = United States Geological Survey|access-date = 2016-07-01 |title = Mineral Commodity Summaries 2016: Arsenic}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1 || {{CHN}} || 25,000 T | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2 || {{MAR}} || 8,800 T | |||

| |- | |||

| | 3 || {{RUS}} || 1,500 T | |||

| |- | |||

| | 4 || {{BEL}} || 1,000 T | |||

| |- | |||

| | 5 || {{BOL}} || 52 T | |||

| |- | |||

| | 6 || {{JAP}} || 45 T | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | — || '''World Total (rounded)''' || '''36,400 T''' | |||

| | ] || 1673 ] | |||

| |} | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatfusion_kjpmol | (gray) 24.44 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatvaporiz_kjpmol | ? 34.76 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatcapacity_jpmolkat25 | 24.64 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_vaporpressure_katpa | 553 | 596 | 646 | 706 | 781 | 874 | comment= }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_atomicprop | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_crystalstruct | rhombohedral }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_oxistates | ±'''3''', 5<br />(mildly ]ic oxide) }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_electroneg_pauling | 2.18 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_ionizationenergies4 | 947.0 | 1798 | 2735 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicradius_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicradiuscalc_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_covalentradius_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_vanderwaalsrad_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_miscellaneous | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_magnetic | no data }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_eresist_ohmmat20 | 333 n}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_thermalcond_wpmkat300k | 50.2 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_youngsmodulus_gpa | 8 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_bulkmodulus_gpa | 22 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_mohshardness | 3.5 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_brinellhardness_mpa | 1440 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_cas_number | 7440-38-2 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_begin | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_decay2 | mn=73 | sym=As | na=] | hl=] ] | dm1=] | de1=- | pn1=73 | ps1=] | dm2=] | de2=0.05], 0.01D, ] | pn2= | ps2=- }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_decay4 | mn=74 | sym=As | na=] | hl=] d | dm1=ε | de1=- | pn1=74 | ps1=] | dm2=] | de2=0.941 | pn2=74 | ps2=] | dm3=γ | de3=0.595, 0.634 | pn3= | ps3=- | dm4=] | de4=1.35, 0.717 | pn4=74 | ps4=] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_stable | mn=75 | sym=As | na=100% | n=42 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_end}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_footer | color1=#cccc99 | color2=black }} | |||

| == History == | |||

| '''Arsenic''' (]: {{IPA|/ˈɑː(r)sənik/}}) is a ] in the ] that has the symbol '''As''' and ] 33. This is a notoriously poisonous ] that has many ] forms; yellow, black and gray are a few that are regularly seen. Arsenic and its compounds are used as ], ]s, ]s and various ]s. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] for arsenic]] | |||

| The word ''arsenic'' has its origin in the ] word {{lang|arc|ܙܪܢܝܟܐ}} ''zarnika'',<ref name="etymonline.com">{{OEtymD|arsenic|access-date = 2010-05-15}}</ref><ref name="oed |arsenic">{{oed |arsenic}}</ref> from Arabic al-zarnīḵ {{lang|ar|الزرنيخ}} 'the ]', based on ] zar ("gold") from the word {{lang|fa|زرنيخ}} ''zarnikh'', meaning "yellow" (literally "gold-colored") and hence "(yellow) orpiment". It was adopted into ] (using ]) as ''arsenikon'' ({{lang|grc|ἀρσενικόν}}) – a neuter form of the Greek adjective ''arsenikos'' ({{lang|grc| ἀρσενικός}}), meaning "male", "virile". | |||

| ==Notable characteristics== | |||

| Arsenic is very similar chemically to its predecessor ], so much so that it will partly substitute for phosphorus in biochemical reactions and is thus ]ous. When heated rapidly it ] to ]; the fumes from this reaction have an odor resembling ]. Arsenic and some arsenic compounds can also ] upon heating, converting directly to a gaseous form. Elemental arsenic is found in two solid forms: yellow and gray/metallic, with ] of 1.97 and 5.73, respectively. | |||

| ]-speakers adopted the Greek term as {{Lang|la|arsenicum}}, which in French ultimately became {{Lang|fr|arsenic}}, whence the English word "arsenic".<ref name="oed |arsenic"/> | |||

| ==Applications== | |||

| Arsenic sulfides (orpiment, ]) and oxides have been known and used since ancient times.<ref name="Curiosa">{{cite journal |last1=Bentley |first1=Ronald |last2=Chasteen |first2=Thomas G. |title=Arsenic Curiosa and Humanity |journal=The Chemical Educator |date=April 2002 |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=51–60 |doi=10.1007/s00897020539a }}</ref> ] ({{circa|300 AD}}) describes roasting ''sandarach'' (realgar) to obtain ''cloud of arsenic'' (]), which he then ] to gray arsenic.<ref>{{cite book|title= Makers of Chemistry|author= Holmyard John Eric|publisher= Read Books|date= 2007|isbn= 978-1-4067-3275-7}}</ref> As the symptoms of ] are not very specific, the substance was frequently used for murder until the advent in the 1830s of the ], a sensitive chemical test for its presence. (Another less sensitive but more general test is the ].) Owing to its use by the ruling class to murder one another and its potency and discreetness, arsenic has been called the "poison of kings" and the "king of poisons".<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hughes |first1=Michael F. |last2=Beck |first2=Barbara D. |last3=Chen |first3=Yu |last4=Lewis |first4=Ari S. |last5=Thomas |first5=David J. |date=2011 |title=Arsenic Exposure and Toxicology: A Historical Perspective |journal=Toxicological Sciences |volume=123 |issue=2 |pages=305–332 |doi=10.1093/toxsci/kfr184 |pmc=3179678 |pmid=21750349}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1177/0960327107084539 |date = 2007 |title = Arsenic neurotoxicity – a review |volume = 26 |issue = 10 |pages = 823–832 |pmid = 18025055 |journal = Human & Experimental Toxicology |last1 = Vahidnia |first1 = A. |last2 = Van Der Voet |first2 = G. B. |last3 = De Wolff |first3 = F. A. |bibcode = 2007HETox..26..823V |s2cid = 24138885}}</ref> Arsenic became known as "the inheritance powder" due to its use in killing family members in the ].<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-815846-3.00001-6 |chapter=An introduction to clinical and forensic toxicology |title=Toxicology Cases for the Clinical and Forensic Laboratory |date=2020 |last1=Ketha |first1=Hema |last2=Garg |first2=Uttam |pages=3–6 |isbn=978-0-12-815846-3 |quote=Arsenic was nicknamed 'the inheritance powder' as it was commonly used to poison family members for a fortune in the Renaissance era.}}</ref> | |||

| ] has been used, well into the 20th century, as an ] on ]s (resulting in ] to those working the sprayers), and ] has even been recorded in the 19th century as a ] in ]. In the last half century, ] (MSMA), a less toxic organic form of arsenic, has replaced lead arsenate's role in agriculture. | |||

| ], Cornwall]] | |||

| The application of most concern to the general public is probably that of ] which has been treated with ] ("CCA", or "]", and the vast majority of older "]" wood). CCA timber is still in widespread use in many countries, and was heavily used during the latter half of the 20th century as a structural, and outdoor ], where there was a risk of ], or ] infestation in untreated timber. Although widespread bans followed the publication of studies which showed low-level leaching from in-situ timbers (such as children's ] equipment) into surrounding ], the most serious risk is presented by the burning of CCA timber. Recent years have seen fatal animal poisonings, and serious human poisonings resulting from the ingestion - directly or indirectly - of wood ash from CCA timber (the lethal human dose is approximately 20 grams of ash). Scrap CCA construction timber continues to be widely burnt through ignorance, in both commercial, and domestic fires. Safe disposal of CCA timber remains patchy, and little practiced, there is concern in some quarters about the widespread ] disposal of such timber. | |||

| During the ], arsenic was melted with copper to make ].<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.2307/530550 |last1 = Lechtman |first1 = H. |title = Arsenic Bronze: Dirty Copper or Chosen Alloy? A View from the Americas |journal = Journal of Field Archaeology |volume = 23 |issue = 4 |pages = 477–514 |date = 1996 |jstor = 530550}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |jstor = 501586|title= Early Arsenical Bronzes—A Metallurgical View |journal= American Journal of Archaeology |volume= 71 |issue= 1|date= 1967|pages= 21–26|author= Charles, J. A. |doi = 10.2307/501586}}</ref> | |||

| During the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, a number of arsenic compounds have been used as medicines, including ] (by ]) and ] (by Thomas Fowler). | |||

| ] described the isolation of arsenic before 815 AD.<ref name="Sarton">], ''Introduction to the History of Science''. "We find in his writings preparation of various substances (e.g., basic lead carbonatic, arsenic and antimony from their sulphides)."</ref> ] (Albert the Great, 1193–1280) later isolated the element from a compound in 1250, by heating soap together with ].<ref name="BuildingBlocks451-3">{{cite book |last= Emsley |first= John |title= Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements |date= 2001 |isbn= 978-0-19-850341-5|pages= 43, 513, 529 |publisher= ] |location= Oxford}}</ref> In 1649, ] published two ways of preparing arsenic.<ref>{{cite book|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=PTgwAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA84 |pages = 84–|title= A general system of chemical knowledge, and its application to the phenomena of nature and art|last1= Fourcroy|first1= Antoine-François |author-link1 = Antoine-François de Fourcroy |date= 1804}}</ref> Crystals of elemental (native) arsenic are found in nature, although rarely. | |||

| Arsphenamine as well as ] was indicated for ] and ], but has been superseded by modern ]. | |||

| Arsenic trioxide has been used in a variety of ways over the past 200 years, but most commonly in the treatment of ]. The ] in 2000 approved this compound for the treatment of patients with ] that is resistant to ].<ref>Antman, Karen H. (2001). . Introduction to a supplement to ''The Oncologist''. '''6''' (Suppl 2), 1-2. PMID 11331433.</ref> It was also used as ]'s solution in ].<ref>Huet ''et.al''. Noncirrhotic presinusoidal portal hypertension associated with chronic arsenical intoxication. ''Gastroenterology'' 1975;'''68'''(5 Pt 1):1270-7. | |||

| PMID 1126603 </ref> | |||

| ] (impure ]), often claimed as the first synthetic ], was synthesized in 1760 by ] through the reaction of ] with ].<ref>{{cite journal |title = Cadet's Fuming Arsenical Liquid and the Cacodyl Compounds of Bunsen |first = Dietmar |last = Seyferth |journal = Organometallics |date = 2001 |volume = 20 |issue = 8 |pages = 1488–1498 |doi = 10.1021/om0101947|doi-access = free}}</ref> | |||

| Copper acetoarsenite was used as a green ] known under many different names, including ] and Emerald Green. It caused numerous ]s. | |||

| ] of a chemist giving a public demonstration of arsenic, 1841]] | |||

| Other uses; | |||

| * Various ] insecticides and poisons. | |||

| * ] is an important ] material, used in ]s. Circuits made using the compound are much faster (but also much more expensive) than those made in ]. Unlike silicon it is ], and so can be used in ]s and ]s to directly convert ] into ]. | |||

| * Also used in ] and ]. | |||

| In the ], women would eat "arsenic" ("]" or arsenic trioxide) mixed with vinegar and ] to improve the ] of their faces, making their skin paler (to show they did not work in the fields).<ref>{{Cite news |last=Fould |first=H. S. |date=13 February 1898 |title=Display Ad 48 – no Title |trans-title="LADIES" in large print at the top; advertises "Dr. Campbell's Safe Arsenic Complexion Wafers and Fould's Medicated Arsenic Complexion Soap" |newspaper=] |location=New York |page=28 |publication-place=Washington, DC |id={{ProQuest|143995174}}}}</ref> The accidental use of arsenic in the adulteration of foodstuffs led to the ] in 1858, which resulted in 21 deaths.<ref name="Food">{{cite journal|journal = British Food Journal |volume = 101 |issue = 4 |date = 1999 |pages = 274–283 |title = Viewpoint: the story so far: An overview of developments in UK food regulation and associated advisory committees |first = Alan |last = Turner | doi =10.1108/00070709910272141}}</ref> From the late-18th century wallpaper production began to use dyes made from arsenic,<ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| The word ''arsenic'' is borrowed from the ] word زرنيخ ''Zarnikh'' meaning "yellow ]". ''Zarnikh'' was borrowed by ] as ''arsenikon''. Arsenic has been known and used in ] and elsewhere since ancient times. As the symptoms of ] were somewhat ill-defined, it was frequently used for ] until the advent of the ], a sensitive chemical test for its presence. (Another less sensitive but more general test is the ].) Due to its use by the ruling class to murder one another and its incredible potency and discreetness, arsenic has been called the ''Poison of Kings and the King of Poisons''. | |||

| |last1 = Whorton | |||

| |first1 = James C. | |||

| |date = 28 January 2010 | |||

| |orig-date = 2010 | |||

| |chapter = Walls of Death | |||

| |title = The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=YnVNX3drptkC | |||

| |edition = reprint | |||

| |publication-place = Oxford | |||

| |publisher = Oxford University Press | |||

| |page = 205 | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-19-162343-1 | |||

| |access-date = 1 October 2023 | |||

| |quote = At first, green papers were coloured with the traditional mineral pigment verdigris or buy mixing blues and yellows of plant origin. But once Scheele's green began to be produced in quantity, it was adopted as an improvement over the old colours and became a common constituent in wallpaper by 1800. | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| which was thought to increase the pigment's brightness.<ref>{{cite book |last1= Hawksley |first1= Lucinda |title= Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper & Arsenic in the Victorian Home |date= 2016 |publisher= Thames & Hudson |location= New York}}</ref> One account of the illness and ] of ] implicates arsenic poisoning involving wallpaper.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |last1 = Cullen | |||

| |first1 = William R. | |||

| |year = 2008 | |||

| |chapter = 4.7.1 Was it the Arsenic in the Wallpaper? | |||

| |title = Is Arsenic an Aphrodisiac?: The Sociochemistry of an Element | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=yyaTdY4UGLMC | |||

| |publisher = Royal Society of Chemistry | |||

| |page = 146 | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-85404-363-7 | |||

| |access-date = 1 October 2023 | |||

| |quote = The wallpaper-as-arsenic-source of poison made the headlines in 1982 when analysis of a sample of wallpaper from the living room in Longwood, Napoleon's residence on St. Helena, revealed arsenic concentrations of about 0.12 g/m<sup>2</sup>. | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Two arsenic pigments have been widely used since their discovery – ] in 1814 and ] in 1775. After the toxicity of arsenic became widely known, these chemicals were used less often as pigments and more often as insecticides. In the 1860s, an arsenic byproduct of dye production, London Purple, was widely used. This was a solid mixture of arsenic trioxide, aniline, lime, and ferrous oxide, insoluble in water and very toxic by inhalation or ingestion<ref>{{cite web|url= https://cameochemicals.noaa.gov/chemical/3779|title= London purple|access-date= 24 June 2023|publisher= National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration}}</ref> But it was later replaced with ], another arsenic-based dye.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Colour in the Garden: 'Malignant Magenta' | first = Susan W. | last = Lanman | journal = Garden History | volume = 28 | issue = 2 | date = 2000 | pages= 209–221 |jstor= 1587270 | doi = 10.2307/1587270}}</ref> With better understanding of the toxicology mechanism, two other compounds were used starting in the 1890s.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1021/ie50201a018 | title = Insecticides and Fungicides | date = 1926 | last1 = Holton | first1 = E. C. | journal = Industrial & Engineering Chemistry | volume = 18 | issue = 9 | pages = 931–933}}</ref> ] and ] were used widely as insecticides until the discovery of ] in 1942.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00180-6 | title = An assessment of the amounts of arsenical pesticides used historically in a geographical area | date = 1998 | last1 = Murphy | first1 = E. A. | last2 = Aucott | first2 = M. | journal = Science of the Total Environment | volume = 218 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 89–101 | bibcode = 1998ScTEn.218...89M }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | url = https://archive.org/details/CAT85816421 |page= | title = Important Insecticides: Directions for Their Preparation and Use | publisher = U.S. Department of Agriculture | last1 = Marlatt | first1 = C. L. | date = 1897}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=eIJVHFCBI_wC&pg=PA248 |title = Paradise Under Glass: An Amateur Creates a Conservatory Garden |isbn = 978-0-06-199130-1 |last1 = Kassinger |first1 = Ruth |year= 2010|publisher = Harper Collins }}</ref> | |||

| During the Bronze Age, arsenic was often included in the bronze (mostly as an impurity), which made the alloy harder. | |||

| In small doses, soluble arsenic compounds act as ]s, and were once popular as medicine by people in the mid-18th to 19th centuries;<ref name="Holl">{{cite book|publisher = Walter de Gruyter|date = 1985|edition = 91–100|pages = 675–681|isbn = 978-3-11-007511-3|title = Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie|first = Arnold F.|last = Holleman|author2= Wiberg, Egon|author3= Wiberg, Nils|language = de|chapter = Arsen}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Haller |first1=John S. |title=Therapeutic Mule: The Use of Arsenic in the Nineteenth Century Materia Medica |journal=Pharmacy in History |date=1975 |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=87–100 |jstor=41108920 |pmid=11610136 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Parascandola |first=John |isbn=978-1-59797-809-5 |via=] |chapter=5. What Kills Can Cure: Arsenic in Medicine |oclc=817901966 |pages=145–172 |chapter-url=https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/1650011 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42297 |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=2011 |language=English |publication-place=], Nebraska, United States of America |title=King of Poisons: A History of Arsenic }}</ref> this use was especially prevalent for sport animals such as ] or ]s and continued into the 20th century.<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-420227-6.00014-1 |chapter=Metalloids |title=Veterinary Toxicology for Australia and New Zealand |date=2017 |last1=Cope |first1=Rhian |pages=255–277 |isbn=978-0-12-420227-6 }}</ref> | |||

| ] is believed to have been the first to isolate the | |||

| A 2006 study of the remains of the Australian racehorse ] determined that its 1932 death was caused by a massive overdose of arsenic. Sydney veterinarian Percy Sykes stated, "In those days, arsenic was quite a common tonic, usually given in the form of a solution (]) ... It was so common that I'd reckon 90 per cent of the horses had arsenic in their system."<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2006-10-23/phar-lap-arsenic-claims-premature-expert/1292814|title=Phar Lap arsenic claims premature: expert|date=2006-10-23|newspaper=ABC News|access-date=2016-06-14}}</ref> | |||

| element in 1250. In 1649 ] published two ways of preparing arsenic. | |||

| == Applications == | |||

| The ] symbol for arsenic is shown below.] | |||

| === Agricultural === | |||

| In the ], arsenic was mixed with ] and ] and eaten by women to improve the ] of their faces, making their skin more fair to show they did not work in the fields. Arsenic was also rubbed into the faces and arms of women to improve their complexion. | |||

| ] is a controversial arsenic compound used as a feed ingredient for chickens.]] | |||

| The toxicity of arsenic to insects, bacteria, and fungi led to its use as a ].<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.2134/jeq2004.0173 |last1 = Rahman |first1 = F. A. |last2 = Allan |first2 = D. L. |last3 = Rosen |first3 = C. J. |last4 = Sadowsky |first4 = M. J. |title = Arsenic availability from chromated copper arsenate (CCA)-treated wood |journal = Journal of Environmental Quality |volume = 33 |issue = 1 |pages = 173–180 |date = 2004 |pmid = 14964372}}</ref> In the 1930s, a process of treating wood with ] (also known as CCA or ]) was invented, and for decades, this treatment was the most extensive industrial use of arsenic. An increased appreciation of the toxicity of arsenic led to a ban of CCA in consumer products in 2004, initiated by the European Union and United States.<ref>{{cite book|title = Environmental Chemistry: Green Chemistry and Pollutants in Ecosystems|editor = Lichtfouse, Eric|editor2 = Schwarzbauer, Jan|editor3 = Robert, Didier|date = 2004|isbn = 978-3-540-22860-8|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=IDGLh_cWAIwC|chapter = Electrodialytical Removal of Cu, Cr and As from Threaded Wood|first = Eric|last = Lichtfouse |publisher = Springer|location = Berlin}}</ref><ref name="round">{{cite journal|journal = Talanta|volume = 58|issue = 1|date = 2002|pages = 201–235|doi = 10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00268-0|title = Arsenic round the world: a review|first1 = Badal Kumar|last1 = Mandal|pmid = 18968746|last2 = Suzuki|first2 = K. T.}}</ref> However, CCA remains in heavy use in other countries (such as on Malaysian rubber plantations).<ref name = Ullmann /> | |||

| ==Arsenic in drinking water== | |||

| {{main|Arsenic contamination of groundwater}} | |||

| ] has led to a massive epidemic of arsenic poisoning in ]<ref>Andrew Meharg, Venomous Earth - How Arsenic Caused The World's Worst Mass Poisoning, , 2005.</ref> and neighbouring countries. It is estimated that approximately 57 million people<!--just Bangladesh, or total?--> are drinking ] with arsenic concentrations elevated above the ]'s standard of 10 ]. The arsenic in the groundwater is of natural origin, and is released from the sediment into the groundwater due to the anoxic conditions of the subsurface. This groundwater began to be used after western ] instigated a massive tube ] drinking-water program in the late ]. This program was designed to prevent drinking of bacterially-contaminated surface waters, but unfortunately failed to test for arsenic in the groundwater.(2) Many other countries in ], such as ], ], and ], are thought to have geological environments similarly conducive to generation of high-arsenic groundwaters. | |||

| Arsenic was also used in various agricultural insecticides and poisons. For example, ] was a common insecticide on ]s,<ref>{{cite conference|last = Peryea|first = F. J.|title = Historical use of lead arsenate insecticides, resulting in soil contamination and implications for soil remediation|conference = 16th World Congress of Soil Science|place = Montpellier, France|date = 20–26 August 1998|url = http://soils.tfrec.wsu.edu/leadhistory.htm|url-status = dead|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081207174027/http://soils.tfrec.wsu.edu/leadhistory.htm|archive-date = 7 December 2008}}</ref> but contact with the compound sometimes resulted in brain damage among those working the sprayers. In the second half of the 20th century, ] (MSMA) and ] (DSMA) – less toxic organic forms of arsenic – replaced lead arsenate in agriculture. These organic arsenicals were in turn phased out in the United States by 2013 in all agricultural activities except cotton farming.<ref name="Federal Register">{{cite web |title=Organic Arsenicals; Notice of Receipt of Requests to Voluntarily Cancel or to Amend to Terminate Uses of Certain Pesticide Registrations |url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2009-07-08/html/E9-16054.htm |website=Federal Register |publisher=Government Printing Office |access-date=18 July 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Monosodium Methanearsonate (MSMA), an Organic Arsenical |date=22 April 2015 |url=https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/monosodium-methanearsonate-msma-organic-arsenical |publisher=Environmental Protection Agency |access-date=18 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

| The northern United States, including parts of ], ], ] and the Dakotas are known to have significant concentrations of arsenic in ground water. | |||

| The biogeochemistry of arsenic is complex and includes various adsorption and desorption processes. The toxicity of arsenic is connected to its solubility and is affected by pH. Arsenite ({{chem2|AsO3(3-)}}) is more soluble than arsenate ({{chem2|AsO4(3-)}}) and is more toxic; however, at a lower pH, arsenate becomes more mobile and toxic. It was found that addition of sulfur, phosphorus, and iron oxides to high-arsenite soils greatly reduces arsenic phytotoxicity.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.crcpress.com/Trace-Elements-in-Soils-and-Plants-Third-Edition/Kabata-Pendias/p/book/9780849315756|title=Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, Third Edition|website=CRC Press|access-date=2016-08-02|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160821154852/https://www.crcpress.com/Trace-Elements-in-Soils-and-Plants-Third-Edition/Kabata-Pendias/p/book/9780849315756|archive-date=21 August 2016|url-status = dead}}</ref> | |||

| Arsenic can be removed from drinking water through co-precipitation of iron minerals by oxidation and filtering. When this treatment fails to produce acceptable results, adsorptive arsenic removal media may be utilized. Several adsorptive media systems have been approved for point of service use in a study funded by the United States ] (U.S.EPA) and the ] (NSF). | |||

| Arsenic is used as a feed additive in ] and ], in particular it was used in the U.S. until 2015 to increase weight gain, improve ], and prevent disease.<ref>{{cite journal|journal = Environmental Health Perspectives|date = 2005|volume = 113|issue = 9|pages = 1123–1124|doi = 10.1289/ehp.7834|pmid = 16140615|pmc = 1280389|title = Arsenic: A Roadblock to Potential Animal Waste Management Solutions|first1 = Keeve E.|last1 = Nachman|last2 = Graham|first2 = Jay P.|last3 = Price|first3 = Lance B.|last4 = Silbergeld|first4 = Ellen K.| bibcode=2005EnvHP.113.1123N }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2-c5.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp2-c5.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|title=Arsenic |at=Section 5.3, p. 310|publisher=Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry}}</ref> An example is ], which had been used as a ] starter by about 70% of U.S. broiler growers.<ref>{{cite journal|title =A Broad View of Arsenic|date = 2007|volume = 86|pages = 2–14|journal = Poultry Science|first = F. T.|last =Jones|pmid =17179408|issue =1|doi=10.1093/ps/86.1.2|doi-access =free}}</ref> In 2011, Alpharma, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc., which produces roxarsone, voluntarily suspended sales of the drug in response to studies showing elevated levels of inorganic arsenic, a carcinogen, in treated chickens.<ref name="FDAQ&A">{{cite web |author=Staff |title=Questions and Answers Regarding 3-Nitro (Roxarsone) |url=https://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/ProductSafetyInformation/ucm258313.htm |date=8 June 2011 |publisher=] |access-date=2012-09-21 }}</ref> A successor to Alpharma, ], continued to sell ] until 2015, primarily for use in turkeys.<ref name="FDAQ&A" /> | |||

| ==Occurrence== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] also called mispickel (]]As) is the most common ] from which, on heating, the arsenic sublimes leaving ferrous sulfide. Other arsenic minerals include ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| === Medical use === | |||

| The most important compounds of arsenic are ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Paris Green, calcium arsenate, and lead arsenate have been used as ] ]s and ]s. Orpiment and realgar were formerly used as painting pigments, though they have somewhat fallen out of use due to their toxicity and reactivity. It is sometimes found native, but usually combined with ], ], ], ], ], or ]. | |||

| During the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a number of arsenic compounds were used as medicines, including ] (by ]) and ] (by ]), for treating diseases such as cancer or ].<ref name="ITOM">{{cite book |last1=Gibaud |first1=Stéphane |last2=Jaouen |first2=Gérard |title=Medicinal Organometallic Chemistry |chapter=Arsenic-Based Drugs: From Fowler's Solution to Modern Anticancer Chemotherapy |date=2010 |volume=32 |pages=1–20 |doi= 10.1007/978-3-642-13185-1_1 |series=Topics in Organometallic Chemistry |isbn=978-3-642-13184-4|bibcode=2010moc..book....1G }}</ref> Arsphenamine, as well as ], was indicated for ], but has been superseded by modern ]. However, arsenicals such as ] are still used for the treatment of ], since although these drugs have the disadvantage of severe toxicity, the disease is almost uniformly fatal if untreated.<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 28673422 | doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31510-6 | volume=390 | issue=10110 | title=Human African trypanosomiasis | year=2017 |vauthors=Büscher P, Cecchi G, Jamonneau V, Priotto G | journal=Lancet | pages=2397–2409| s2cid=4853616 }}</ref> In 2000 the US ] approved arsenic trioxide for the treatment of patients with ] that is resistant to ].<ref>{{cite journal|last = Antman |first = Karen H.|date = 2001| title = The History of Arsenic Trioxide in Cancer Therapy|volume = 6|issue =Suppl 2|pages = 1–2|pmid = 11331433|doi = 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_2-1|journal = The Oncologist|doi-access = free}}</ref> | |||

| In addition to the inorganic forms mentioned above, arsenic also occurs in various organic forms in the environment. Inorganic arsenic and its compounds, upon entering the ], are progressively metabolised to a less toxic form of arsenic through a process of ]. | |||

| A 2008 paper reports success in locating tumors using arsenic-74 (a positron emitter). This isotope produces clearer ] images than the previous radioactive agent, ]-124, because the body tends to transport iodine to the thyroid gland producing signal noise.<ref>{{cite journal|journal = Clinical Cancer Research|date = 2008|volume = 14|pages =1377–1385|doi = 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1516|title = Vascular Imaging of Solid Tumors in Rats with a Radioactive Arsenic-Labeled Antibody that Binds Exposed Phosphatidylserine|last1 = Jennewein|first1 =Marc|pmid = 18316558|issue = 5|last2 = Lewis|first2 = M. A.|last3 = Zhao|first3 = D.|last4 = Tsyganov|first4 = E.|last5 = Slavine|first5 = N.|last6 = He|first6 = J.|last7 = Watkins|first7 = L.|last8 = Kodibagkar|first8 = V. D.|last9 = O'Kelly|first9 = S.|first10=P. |last10=Kulkarni|first11=P. |last11=Antich|first12=A. |last12=Hermanne|first13=F. |last13=Rösch|first14=R. |last14=Mason|first15=Ph.|last15=Thorpe |pmc = 3436070}}</ref> ]s of arsenic have shown ability to kill cancer cells with lesser ] than other arsenic formulations.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Subastri |first1=Ariraman |last2=Arun |first2=Viswanathan |last3=Sharma |first3=Preeti |last4=Preedia babu |first4=Ezhuthupurakkal |last5=Suyavaran |first5=Arumugam |last6=Nithyananthan |first6=Subramaniyam |last7=Alshammari |first7=Ghedeir M. |last8=Aristatile |first8=Balakrishnan |last9=Dharuman |first9=Venkataraman |last10=Thirunavukkarasu |first10=Chinnasamy |title=Synthesis and characterisation of arsenic nanoparticles and its interaction with DNA and cytotoxic potential on breast cancer cells |journal=Chemico-Biological Interactions |date=November 2018 |volume=295 |pages=73–83 |doi=10.1016/j.cbi.2017.12.025 |pmid=29277637 |bibcode=2018CBI...295...73S |s2cid=1816043 }}</ref> | |||

| ''See also ], ].'' | |||

| == |

=== Alloys === | ||

| ] | |||

| Arsenic and many of its compounds are especially potent poisons. Arsenic disrupts ] production through several mechanisms including ] of the metabolic ] ] during ].{{fact}} At the level of the citric acid cycle, arsenic inhibits ] and by competing with phosphate it uncouples ], thus inhibiting energy-linked reduction of ], mitochondrial respiration, and ATP synthesis. Hydrogen peroxide production is also increased, which might form reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. Arsenic kills by enzyme inhibtion because enzymes are the best documented targets of metals; in this case, it causes toxicity but can also play a protective role.<ref>Casarett and Doull's Essentials of Toxicology 2003</ref> These metabolic interferences lead to death from multi-system ] (see ]) probably from necrotic cell death, not ]. A ] reveals brick red colored ], due to severe ]. | |||

| The main use of arsenic is in alloying with lead. Lead components in ] are strengthened by the presence of a very small percentage of arsenic.<ref name = Ullmann /><ref>{{cite journal|doi =10.1016/0378-7753(94)01973-Y|title =Lead alloys: Past, present and future|date =1995|last1 =Bagshaw|first1 =N. E.|journal =Journal of Power Sources|volume =53|issue =1|pages =25–30|bibcode = 1995JPS....53...25B }}</ref> ] of ] (a copper-zinc alloy) is greatly reduced by the addition of arsenic.<ref>{{cite book|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=1hSJcC9zwFIC&pg=PA123|pages =123–124| chapter = Dealloying|title = Copper: Its Trade, Manufacture, Use, and Environmental Status|isbn = 978-0-87170-656-0|last1 = Joseph|first1 = Günter|last2 = Kundig|first2 = Konrad J. A|last3 = Association|first3 = International Copper|date = 1999|publisher =ASM International}}</ref> "Phosphorus Deoxidized Arsenical Copper" with an arsenic content of 0.3% has an increased corrosion stability in certain environments.<ref>{{cite book |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=cXkNMB1vBesC&pg=SA5-PA6| page = 6 |title = The Metals Databook |isbn = 978-0-07-462300-8 |author1 = Nayar |date = 1997| publisher = McGraw-Hill }}</ref> ] is an important ] material, used in ]s. Circuits made from GaAs are much faster (but also much more expensive) than those made from ]. Unlike silicon, GaAs has a ], and can be used in ]s and ]s to convert electrical energy directly into light.<ref name = Ullmann /> | |||

| Elemental arsenic and arsenic compounds are classified as "]" and "dangerous for the environment" in the ] under ]. | |||

| === Military === | |||

| After ], the United States built a stockpile of 20,000 tons of ] ] (ClCH=CHAsCl<sub>2</sub>), an ] ] (blister agent) and ] irritant. The stockpile was neutralized with ] and dumped into the ] in the 1950s.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://library.thinkquest.org/05aug/00639/en/w_chemical_blister.html|publisher = Code Red – Weapons of Mass Destruction |title = Blister Agents|access-date = 2010-05-15 }}</ref> During the ], the United States used ], a mixture of ] and its acid form, as one of the ] to deprive North Vietnamese soldiers of foliage cover and rice.<ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1016/0006-3207(72)90043-2|title = Herbicides in war: Current status and future doubt|date = 1972|last1 = Westing|first1 = Arthur H.|journal = Biological Conservation|volume = 4|issue = 5|pages = 322–327| bibcode=1972BCons...4..322W }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1 = Westing| first1 = Arthur H.|title =Forestry and the War in South Vietnam|journal = Journal of Forestry|volume = 69|pages = 777–783|date = 1971|url = http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/saf/jof/1971/00000069/00000011/art00008}}</ref><!--https://books.google.com/books?id=agsAAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA37--> | |||

| === Other uses === | |||

| * Copper acetoarsenite was used as a green ] known under many names, including ] and Emerald Green. It caused numerous ]s. ], a copper arsenate, was used in the 19th century as a ] in ].<ref>{{cite book|title = The Poison Paradox: Chemicals as Friends and Foes|chapter = Butter Yellow and Scheele's Green|first = John|last = Timbrell|publisher = Oxford University Press|date = 2005|isbn = 978-0-19-280495-2|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=qYYOtQU37jcC|url-access = registration|url = https://archive.org/details/poisonparadoxche0000timb}}</ref> | |||

| * Arsenic is used in ].<ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1007/BF02519786|title = Industrial exposure to arsenic|date = 1979|last1 = Cross|first1 = J. D.|last2 = Dale|first2 = I. M.|last3 = Leslie|first3 = A. C. D.|last4 = Smith|first4 = H.|journal = Journal of Radioanalytical Chemistry|volume = 48|issue = 1–2|pages = 197–208| bibcode=1979JRNC...48..197C |s2cid = 93714157}}</ref> | |||

| * As much as 2% of produced arsenic is used in lead alloys for ] and bullets.<ref>{{cite book|title = Engineering Properties and Applications of Lead Alloys|chapter = XIV. Ammunition|first = Sivaraman|last = Guruswamy|publisher = CRC Press|date = 1999|isbn = 978-0-8247-8247-4|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=TtGmjOv9CUAC|pages = 569–570}}</ref> | |||

| * Arsenic is added in small quantities to alpha-brass to make it ]. This grade of brass is used in plumbing fittings and other wet environments.<ref>{{cite book|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=sxkPJzmkhnUC&pg=PA390|chapter = Dealloying|page =390|isbn = 978-0-87170-726-0|title = Copper and copper alloys|last1 = Davis |first1=Joseph R. |author2 = Handbook Committee, ASM International|year= 2001| publisher=ASM International }}</ref> | |||

| * Arsenic is also used for ] sample preservation.<!--https://books.google.com/books?id=aRI9MrpXLqYC&pg=PA93 --> It was also used in embalming fluids historically.<ref>Christine Quigley, ''Modern Mummies: The Preservation of the Human Body in the Twentieth Century'', p 6.</ref> | |||

| * Arsenic was used in the ] process up until the 1980s.<ref>{{cite journal| last1=Marte | first1=Fernando | last2=Pequignot | first2=Amandine| title=Arsenic in Taxidermy Collections: History, Detection, and Management |journal=Collection Forum|year=2006| url=https://repository.si.edu/handle/10088/8134|hdl=10088/8134|volume=21|issue=1–2|pages=143–150}}</ref> | |||

| * Arsenic was used as an opacifier in ceramics, creating white glazes.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Parmelee |first1=Cullen W. |title=Ceramic Glazes |date=1947 |publisher=Cahners Books |location=Boston|page=61 |edition=3rd}}</ref> | |||

| * Until recently, arsenic was used in optical glass. Modern glass manufacturers have ceased using both arsenic and lead.<ref>{{cite book|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Qt7sNqoP_CkC&pg=PA68|page =68|title = Pollution technology review 214: Mercury and arsenic wastes: removal, recovery, treatment, and disposal|publisher = William Andrew|date = 1993|isbn = 978-0-8155-1326-1|chapter = Arsenic Supply Demand and the Environment|author=United States Environmental Protection Agency}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kumar |first1=Mahendra |last2=Seth |first2=Aparna |last3=Singh |first3=Alak Kumar |last4=Rajput |first4=Manish Singh |last5=Sikandar |first5=Mohd |date=2021-12-01 |title=Remediation strategies for heavy metals contaminated ecosystem: A review |journal=Environmental and Sustainability Indicators |volume=12 |pages=100155 |doi=10.1016/j.indic.2021.100155 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2021EnvSI..1200155K }}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Humans |first=IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to |title=Exposures in the Glass Manufacturing Industry |date=1993 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499748/ |work=Beryllium, Cadmium, Mercury, and Exposures in the Glass Manufacturing Industry |volume=58 |pages=347–375 |access-date=2024-01-12 |publisher=International Agency for Research on Cancer |language=en |pmid=8022057|pmc=7681308 }}</ref> | |||

| == Biological role == | |||

| {{Main|Arsenic biochemistry}} | |||

| === Bacteria === | |||

| Some species of bacteria obtain their energy in the absence of oxygen by ] various fuels while ] arsenate to arsenite. Under oxidative environmental conditions some bacteria use arsenite as fuel, which they oxidize to arsenate.<ref>{{cite journal|last1 = Stolz|first1 = John F.|last2 = Basu|first2 = Partha|last3 = Santini|first3 = Joanne M.|last4 = Oremland|first4 = Ronald S.|s2cid = 2575554|title = Arsenic and Selenium in Microbial Metabolism|journal = Annual Review of Microbiology|volume = 60|pages = 107–130|date = 2006|doi = 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142053|pmid=16704340| bibcode=2006ARvMb..60..107S }}</ref> The ]s involved are known as ] (Arr).<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00617.x |title = Microbial arsenic: From geocycles to genes and enzymes |date = 2002 |last1 = Mukhopadhyay |first1 = Rita |last2 = Rosen |first2 = Barry P. |last3 = Phung |first3 = Le T. |last4 = Silver |first4 = Simon |journal = FEMS Microbiology Reviews |volume = 26 |issue = 3 |pages = 311–325 |pmid = 12165430| doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| In 2008, bacteria were discovered that employ a version of ] in the absence of oxygen with arsenites as ]s, producing arsenates (just as ordinary photosynthesis uses water as electron donor, producing molecular oxygen). Researchers conjecture that, over the course of history, these photosynthesizing organisms produced the arsenates that allowed the arsenate-reducing bacteria to thrive. One ], PHS-1, has been isolated and is related to the ] '']''. The mechanism is unknown, but an encoded Arr enzyme may function in reverse to its known ].<ref>{{cite journal|author= Kulp, T. R|date = 2008|title = Arsenic(III) fuels anoxygenic photosynthesis in hot spring biofilms from Mono Lake, California|journal = ]|volume = 321 |issue = 5891|pages = 967–970|doi = 10.1126/science.1160799 |pmid= 18703741|last2= Hoeft|first2= S. E.|last3= Asao|first3= M.|last4= Madigan|first4= M. T.|last5= Hollibaugh|first5= J. T.|last6= Fisher|first6= J. C.|last7= Stolz|first7= J. F.|last8= Culbertson|first8= C. W.|last9= Miller|first9= L. G.|first10=R. S.|last10=Oremland|s2cid = 39479754|bibcode = 2008Sci...321..967K}} | |||

| *{{cite magazine |author=Fred Campbell |date=11 August 2008 |title=Arsenic-loving bacteria rewrite photosynthesis rules |magazine=Chemistry World |url=https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/arsenic-loving-bacteria-rewrite-photosynthesis-rules/3000398.article}}</ref> | |||

| In 2011, it was postulated that the '']'' strain ] could be grown in the absence of phosphorus if that element were substituted with arsenic,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Wolfe-Simon|first1=F.|last2=Blum|first2=J. S.|last3=Kulp|first3=T. R.|last4=Gordon|first4=G. W.|last5=Hoeft|first5=S. E.|last6=Pett-Ridge|first6=J.|last7=Stolz|first7=J. F.|last8=Webb|first8=S. M.|last9=Weber|first9=P. K.|date=2011-06-03|title=A Bacterium That Can Grow by Using Arsenic Instead of Phosphorus|journal=Science|language=en|volume=332|issue=6034|pages=1163–1166|doi=10.1126/science.1197258|pmid=21127214|bibcode=2011Sci...332.1163W|s2cid=51834091|url=https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc832429/m2/1/high_res_d/1016932.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc832429/m2/1/high_res_d/1016932.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|doi-access=free}}</ref> exploiting the fact that the ] and ] anions are similar structurally. The study was widely criticised and subsequently refuted by independent researcher groups.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1126/science.1218455 |title = GFAJ-1 is an Arsenate-Resistant, Phosphate-Dependent Organism |date = 2012 |last1 = Erb |first1 = T. J. |last2 = Kiefer |first2 = P. |last3 = Hattendorf |first3 = B. |last4 = Günther |first4 = D. |last5 = Vorholt |first5 = J. A. |journal = Science |volume = 337 |issue = 6093 |pages = 467–470 |pmid = 22773139 |bibcode = 2012Sci...337..467E |s2cid = 20229329 |doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1126/science.1219861 |title = Absence of Detectable Arsenate in DNA from Arsenate-Grown GFAJ-1 Cells |date = 2012 |last1 = Reaves |first1 = M. L. |last2 = Sinha |first2 = S. |last3 = Rabinowitz |first3 = J. D. |last4 = Kruglyak |first4 = L. |last5 = Redfield |first5 = R. J. |journal = Science |volume = 337 |issue = 6093 |pages = 470–473 |pmid = 22773140 |pmc = 3845625 |arxiv = 1201.6643 |bibcode = 2012Sci...337..470R }}</ref> | |||

| === Potential role in higher animals === | |||

| Arsenic may be an essential trace mineral in birds, involved in the synthesis of methionine metabolites.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Živkov Baloš |first1=M. |last2=Jakšić |first2=S. |last3=Ljubojević Pelić |first3=D. |title=The role, importance and toxicity of arsenic in poultry nutrition |journal=World's Poultry Science Journal |date=September 2019 |volume=75 |issue=3 |pages=375–386 |doi=10.1017/S0043933919000394 }}</ref>. However, the role of arsenic in bird nutrition is disputed, as other authors state that arsenic is toxic in small amounts <ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.3389/fvets.2023.1161354 | doi-access=free | title=Heavy metal toxicity in poultry: A comprehensive review | date=2023 | journal=Frontiers in Veterinary Science | volume=10 | pmid=37456954 | pmc=10340091 | vauthors = Aljohani AS }}</ref> | |||

| Some evidence indicates that arsenic is an essential trace mineral in mammals.<ref name=ANut>Anke M. (1986) "Arsenic", pp. 347–372 in Mertz W. (ed.), ''Trace elements in human and Animal Nutrition'', 5th ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press</ref><ref name=UEssent>{{multiref|{{cite journal |journal=Environmental Geochemistry and Health|last1=Uthus |first1=Eric O. |pmid=24197927|title= Evidency for arsenical essentiality|doi=10.1007/BF01783629|volume=14|issue=2|year=1992|pages=55–58|bibcode=1992EnvGH..14...55U |s2cid=22882255}}|Uthus E.O. (1994) "Arsenic essentiality and factors affecting its importance", pp. 199–208 in Chappell W.R, Abernathy C.O, Cothern C.R. (eds.) ''Arsenic Exposure and Health''. Northwood, UK: Science and Technology Letters.}}</ref> | |||

| === Heredity === | |||

| Arsenic has been linked to ], heritable changes in gene expression that occur without changes in ]. These include DNA methylation, histone modification, and ] interference. Toxic levels of arsenic cause significant DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes ] and ], thus increasing risk of ]. These epigenetic events have been studied ''in vitro'' using human ] cells and ''in vivo'' using rat ] cells and peripheral blood ] in humans.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Baccarelli|first1=A.|date=2009|title=Epigenetics and environmental chemicals|journal=Current Opinion in Pediatrics |issue=2 |volume=21 |pages=243–251 |doi=10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832925cc |pmid=19663042|last2=Bollati|first2=V.|pmc=3035853}}</ref> ] (ICP-MS) is used to detect precise levels of intracellular arsenic and other arsenic bases involved in epigenetic modification of DNA.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Nicholis|first1=I.|date=2009|title=Arsenite medicinal use, metabolism, pharmacokinetics and monitoring in human hair| journal=Biochimie| pmid=19527769| doi=10.1016/j.biochi.2009.06.003 |last2=Curis |last3=Deschamps|last4=Bénazeth|volume=91|first2=E.|first3=P.|first4=S.|issue=10|pages=1260–1267}}</ref> Studies investigating arsenic as an epigenetic factor can be used to develop precise biomarkers of exposure and susceptibility. | |||

| The Chinese brake fern ('']'') hyperaccumulates arsenic from the soil into its leaves and has a proposed use in ].<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| | volume = 156 | |||

| | journal = New Phytologist | |||

| | title = Arsenic Distribution and Speciation in the Fronds of the Hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | pages = 195–203 | |||

| | jstor = 1514012 | |||

| | doi = 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00512.x | |||

| | year = 2002 |first5 = S. P. | |||

| | last5 = McGrath | |||

| |first2 = F.-J. | |||

| | last2 = Zhao | |||

| | first1 = E. | |||

| | last3 = Fuhrmann |first3 = M. |first4 = L. Q. | |||

| | last4 = Ma | |||

| | last1 = Lombi | |||

| | pmid = 33873285 | |||

| | doi-access = free | |||

| | bibcode = 2002NewPh.156..195L | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| === Biomethylation === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Inorganic arsenic and its compounds, upon entering the ], are progressively metabolized through a process of ].<ref name="Biomethylation">{{cite journal|title = Biomethylation of Arsenic is Essentially Detoxicating Event|journal = Journal of Health Science|date = 2003|first1 = Teruaki Sakurai|volume = 49|issue = 3|pages = 171–178| doi = 10.1248/jhs.49.171|last1 = Sakurai|doi-access = free}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Reimer|first=K. J.|author2=Koch, I.|author3=Cullen, W.R.|date=2010|title=Organoarsenicals. Distribution and transformation in the environment|volume=7 |pages=165–229|isbn=978-1-84755-177-1|pmid=20877808|doi=10.1039/9781849730822-00165|series=Metal Ions in Life Sciences}}</ref> For example, the mold '']'' produces ] if inorganic arsenic is present.<ref>{{cite journal|first1 = Ronald|last1 = Bentley|title = Microbial Methylation of Metalloids: Arsenic, Antimony, and Bismuth|journal = Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews|date = 2002|volume = 66|issue = 2|pages = 250–271|doi = 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.250-271.2002|pmid = 12040126|last2 = Chasteen|first2 = T. G.|pmc = 120786}}</ref> The organic compound ] is found in some marine foods such as fish and algae, and also in mushrooms in larger concentrations. The average person's intake is about 10–50 μg/day. Values about 1000 μg are not unusual following consumption of fish or mushrooms, but there is little danger in eating fish because this arsenic compound is nearly non-toxic.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Arsenic speciation in the environment|first1 = William R.|last1 = Cullen|journal = Chemical Reviews|date = 1989|volume = 89|issue = 4|pages =713–764|doi = 10.1021/cr00094a002|last2 = Reimer|first2 = Kenneth J.|hdl = 10214/2162|hdl-access = free}}</ref> | |||

| == Environmental issues == | |||

| === Exposure === | |||

| Naturally occurring sources of human exposure include ], weathering of minerals and ores, and mineralized groundwater. Arsenic is also found in food, water, soil, and air.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.html|title = Case Studies in Environmental Medicine (CSEM) Arsenic Toxicity Exposure Pathways|publisher = Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry|access-date = 2010-05-15|archive-date = 4 February 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160204174821/http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=7&po=7|url-status = dead}}</ref> Arsenic is absorbed by all plants, but is more concentrated in leafy vegetables, rice, apple and grape juice, and seafood.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/diet/features/arsenic-food-faq|access-date=2010-04-11 |date=5 December 2011|title=Arsenic in Food: FAQ}}</ref> An additional route of exposure is inhalation of atmospheric gases and dusts.<ref name="atsdr.cdc.gov">. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2009).</ref> | |||

| During the ], arsenic was widely used in home decor, especially wallpapers.<ref>Archived at {{cbignore}} and the {{cbignore}}: {{cite web| url = https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvxnXOoFl20| title = How Victorians Were Poisoned By Their Own Homes {{!}} Hidden Killers {{!}} Absolute Victory | website=YouTube}}{{cbignore}}</ref> In Europe, an analysis based on 20,000 soil samples across all 28 countries show that 98% of sampled soils have concentrations less than 20 mg kg-1. In addition, the As hotspots are related to frequent fertilization and close distance to mining activities.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Fendrich |first1=Arthur Nicolaus |last2=Van Eynde |first2=Elise |last3=Stasinopoulos |first3=Dimitrios M. |last4=Rigby |first4=Robert A. |last5=Mezquita |first5=Felipe Yunta |last6=Panagos |first6=Panos |date=2024-03-01 |title=Modeling arsenic in European topsoils with a coupled semiparametric (GAMLSS-RF) model for censored data |journal=Environment International |language=en |volume=185 |pages=108544 |doi=10.1016/j.envint.2024.108544|doi-access=free |pmid=38452467 |bibcode=2024EnInt.18508544F }}</ref> | |||

| === Occurrence in drinking water === | |||

| {{Main|Arsenic contamination of groundwater}} | |||

| Extensive arsenic contamination of groundwater has led to widespread ] in ]<ref>{{cite book|first = Andrew|last = Meharg|title = Venomous Earth – How Arsenic Caused The World's Worst Mass Poisoning|isbn = 978-1-4039-4499-3|publisher = Macmillan Science|date = 2005|url-access = registration|url = https://archive.org/details/venomousearthhow00meha}}</ref> and neighboring countries.<!--As of this writing,{{when|date=June 2012}}{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} 42 major incidents around the world have been reported on groundwater arsenic contamination.--> It is estimated that approximately 57 million people in the Bengal basin are drinking ] with arsenic concentrations elevated above the ]'s standard of 10 ] (ppb).<ref>{{cite book |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=hMA70VU36qUC&pg=PA317 |page = 317 |title = Arsenic: Environmental Chemistry, Health Threats and Waste Treatment |isbn = 978-0-470-02758-5 |last1 = Henke |first1 = Kevin R. |date = 28 April 2009|publisher = John Wiley & Sons }}</ref> However, a study of cancer rates in ]<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1289/ehp.8704 |journal=Environ. Health Perspect. |volume=114 |issue=7 |pages=1077–1082 |date=2006 |pmid=16835062 |pmc=1513326 |last1=Lamm |first1=S. H. |last2=Engel |first2=A. |last3=Penn |first3=C. A. |last4=Chen |first4=R. |last5=Feinleib |first5=M. |title=Arsenic cancer risk confounder in southwest Taiwan data set|bibcode=2006EnvHP.114.1077L }}</ref> suggested that significant increases in cancer mortality appear only at levels above 150 ppb. The arsenic in the groundwater is of natural origin, and is released from the sediment into the groundwater, caused by the ] of the subsurface. This groundwater was used after local and western ] and the Bangladeshi government undertook a massive shallow tube ] drinking-water program in the late twentieth century. This program was designed to prevent drinking of bacteria-contaminated surface waters, but failed to test for arsenic in the groundwater. Many other countries and districts in Southeast Asia, such as ] and ], have geological environments that produce groundwater with a high arsenic content. ] was reported in ], Thailand, in 1987, and the ] probably contains high levels of naturally occurring dissolved arsenic without being a public health problem because much of the public uses ].<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://antispam.kmutt.ac.th/index.php/JTMP/article/view/14749 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140110085919/http://antispam.kmutt.ac.th/index.php/JTMP/article/view/14749 |url-status = dead|archive-date=2014-01-10 |title=Arsenic in Groundwater in Selected Countries in South and Southeast Asia: A Review |first1=Andrew |last1=Kohnhorst |journal=J Trop Med Parasitol |date=2005 |volume=28 |page=73 }}</ref> In Pakistan, more than 60 million people are exposed to arsenic polluted drinking water indicated by a 2017 report in ]. Podgorski's team investigated more than 1200 samples and more than 66% exceeded the WHO minimum contamination level.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.science.org/content/article/arsenic-drinking-water-threatens-60-million-pakistan|title=Arsenic in drinking water threatens up to 60 million in Pakistan|date=2017-08-23|work=Science {{!}} AAAS|access-date=2017-09-11|language=en}}</ref> | |||