| Revision as of 09:48, 25 December 2018 view sourceAircorn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers38,722 edits →Crops: boldTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:34, 17 November 2024 view source GreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,547,809 edits Move 2 urls. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:URLREQ#time.com | ||

| (348 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Use American English|date=September 2023}} | |||

| {{Redirect|GMO}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | {{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{short description|Organisms whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering methods}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2012}} | |||

| <noinclude>{{good article}}</noinclude><!-- so that the ] content check on ] doesn't produce a spurious {{error}} when it transcludes this page, because ] is only for ], and talk pages are not good articles! --> | |||

| {{Redirect|GMO}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2022}} | |||

| {{Genetic engineering sidebar}} | |||

| A '''genetically modified organism''' ('''GMO''') is any ] whose ]tic material has been altered using ]. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes ] varies, with the most common being an organism altered in a way that "does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural ]".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Food, genetically modified |url=https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/food-genetically-modified |access-date=2023-08-15 |website=www.who.int |language=en}}</ref> A wide variety of organisms have been genetically modified (GM), including animals, plants, and microorganisms. | |||

| Genetic modification can include the introduction of new genes or enhancing, altering, or ] ] genes. In some genetic modifications, genes are transferred ], across ] (creating transgenic organisms), and even across ]. Creating a genetically modified organism is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism and combine it with other genetic elements, including a ] and ] region and often a ]. A number of techniques are available for ]. Recent advancements using ] techniques, notably ], have made the production of GMOs much simpler. ] and ] made the first genetically modified organism in 1973, a bacterium resistant to the antibiotic ]. The first ], a mouse, was created in 1974 by ], and the first plant was produced in 1983. In 1994, the ] tomato was released, the first commercialized ]. The first genetically modified animal to be commercialized was the ] (2003) and the first genetically modified animal to be approved for food use was the ] in 2015. | |||

| Bacteria are the easiest organisms to engineer and have been used for research, food production, industrial protein purification (including drugs), agriculture, and art. There is potential to use them for environmental purposes or as medicine. Fungi have been engineered with much the same goals. Viruses play an important role as ] for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This use is especially relevant to human ]. There are proposals to remove the ] genes from viruses to create vaccines. Plants have been engineered for scientific research, to create new colors in plants, deliver vaccines, and to create enhanced crops. ] are publicly the most controversial GMOs, in spite of having the most human health and environmental benefits.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Smyth SJ | title = The human health benefits from GM crops | journal = Plant Biotechnology Journal | volume = 18 | issue = 4 | pages = 887–888 | date = April 2020 | pmid = 31544299 | pmc = 7061863 | doi = 10.1111/pbi.13261 }}</ref> Animals are generally much harder to transform and the vast majority are still at the research stage. Mammals are the best ]s for humans. Livestock is modified with the intention of improving economically important traits such as growth rate, quality of meat, milk composition, disease resistance, and survival. ] are used for scientific research, as pets, and as a food source. Genetic engineering has been proposed as a way to control mosquitos, a ] for many deadly diseases. Although human gene therapy is still relatively new, it has been used to treat ]s such as ] and ]. | |||

| Many objections have been raised over the development of GMOs, particularly their commercialization. Many of these involve GM crops and whether food produced from them is safe and what impact growing them will have on the environment. Other concerns are the objectivity and rigor of regulatory authorities, contamination of non-genetically modified food, control of the ], ], and the use of ] rights. Although there is a ] that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, GM food safety is a leading issue with critics. ], impact on non-target organisms, and escape are the major environmental concerns. Countries have adopted regulatory measures to deal with these concerns. There are differences in the regulation for the release of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the US and Europe. Key issues concerning regulators include whether GM food should be labeled and the status of gene-edited organisms. | |||

| == Definition == | |||

| A '''genetically modified organism''' ('''GMO''') is any organism whose ]tic material has been altered using ]. A wide variety of organisms have been ], from animals to plants and microorganisms. Genes have been transferred ], across ] (creating transgenic organisms) and even across ]. New genes can be introduced, or ] can be enhanced, altered or ]. GMOs have been used in biological and medical research, production of ]s,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/ProductRegulation/SelectionsFromFDLIUpdateSeriesonFDAHistory/ucm081964.htm|title=Celebrating a Milestone: FDA's Approval of First Genetically-Engineered Product|last=Junod|first=Suzanne White|publisher=U.S. Food and Drug Administration|name-list-format=vanc}}</ref> experimental medicine (e.g. ] and vaccines against the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/trailblazing-gm-vaccines-are-held-back-by-red-tape-mh5cj7rb0|title=Trailblazing GM vaccines 'are held back by red tape'|last=Whipple|first=Tom|date=2016-05-14|publisher=The Times|access-date=2016-05-14|name-list-format=vanc}}</ref>) and agriculture (e.g. ], resistance to ]), with developing uses in conservation.<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Thomas MA, Roemer GW, Donlan CJ, Dickson BG, Matocq M, Malaney J|date=September 2013|title=Ecology: Gene tweaking for conservation|journal=Nature|volume=501|issue=7468|pages=485–6|doi=10.1038/501485a|pmid=24073449}}</ref> | |||

| The definition of a genetically modified organism (GMO) is not clear and varies widely between countries, international bodies, and other communities. At its broadest, the definition of a GMO can include anything that has had its genes altered, including by nature.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/gmoanswers/2016/10/04/nature-and-gmos/|title=Nature, The First Creator of GMOs| vauthors = Chilton MD |date=4 October 2016|website=Forbes|access-date=4 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/first-gmo-8000-years-old-180955199/|title=The First GMO Is 8,000 Years Old| vauthors = Blakemore E |website=Smithsonian|access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref> Taking a less broad view, it can encompass every organism that has had its genes altered by humans, which would include all crops and livestock. In 1993, the '']'' defined genetic engineering as "any of a wide range of techniques ... among them ], ] (''e.g.'', 'test-tube' babies), ]s, ], and gene manipulation."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/newencyclopaedia07ency/page/178|title=The new encyclopaedia Britannica|date=1993|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica|isbn=0-85229-571-5|edition=15th|location=Chicago|pages=|oclc=27665641|url-access=registration}}</ref> The ] (EU) included a similarly broad definition in early reviews, specifically mentioning GMOs being produced by "] and other means of artificial selection"<ref name=":23">Staff {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130514202621/http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/publi/gmo/gmo.pdf|date=14 May 2013}} The European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture, "Genetic engineering: The manipulation of an organism's genetic endowment by introducing or eliminating specific genes through modern molecular biology techniques. A broad definition of genetic engineering also includes selective breeding and other means of artificial selection", Retrieved 5 November 2012</ref> These definitions were promptly adjusted with a number of exceptions added as the result of pressure from scientific and farming communities, as well as developments in science. The EU definition later excluded traditional breeding, in vitro fertilization, induction of ], ], and cell fusion techniques that do not use recombinant nucleic acids or a genetically modified organism in the process.<ref name="EU172">{{Cite journal|author=The European Parliament and the council of the European Union|date=12 March 2001|title=Directive on the release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) Directive 2001/18/EC ANNEX I A|url=https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32001L0018|journal=Official Journal of the European Communities}}</ref><ref name="Freedman-2018">{{cite book | vauthors = Freedman W | chapter=6 ~ Evolution | publisher=] | date=27 August 2018 | url=http://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/environmentalscience/chapter/chapter-6-evolution/ | title=Environmental Science – a Canadian perspective | edition=6}}</ref><ref name=":17" /> | |||

| Another approach was the definition provided by the ], the ], and the ], stating that the organisms must be altered in a way that does "not occur naturally by mating and/or natural ]".<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/y2772e/y2772e04.htm|title=Section 2: Description and Definitions |website=www.fao.org|access-date=3 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/foodsafety/areas_work/food-technology/faq-genetically-modified-food/en/|title=Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods|website=WHO|access-date=3 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/eu-legislation-gmos-overview|title=The EU Legislation on GMOs – An Overview |date=29 June 2010|website=EU Science Hub – European Commission|access-date=3 January 2019}}</ref> Progress in science, such as the discovery of ] being a relatively common natural phenomenon, further added to the confusion on what "occurs naturally", which led to further adjustments and exceptions.<ref>{{Cite web|date=13 October 2016|title=GMOs and Horizontal Gene Transfer|url=https://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/gmos-and-horizontal-gene-transfer/|access-date=9 July 2021|website=NeuroLogica Blog}}</ref> There are examples of crops that fit this definition, but are not normally considered GMOs.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhang C, Wohlhueter R, Zhang H |title=Genetically modified foods: A critical review of their promise and problems |journal=Food Science and Human Wellness |date=September 2016 |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=116–123 |doi=10.1016/j.fshw.2016.04.002 |doi-access=free }}</ref> For example, the grain crop ] was fully developed in a laboratory in 1930 using various techniques to alter its genome.<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Oliver MJ|date=2014|title=Why we need GMO crops in agriculture|journal=Missouri Medicine|volume=111|issue=6|pages=492–507|pmc=6173531|pmid=25665234}}</ref> | |||

| Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolated the gene they wish to insert into the host organism and combine it with other genetic elements, including a ] and ] region and a ]. A number of techniques are available for ]. Recent advancements using ] techniques, notably ], have made the production of GMO's much simpler. ] and ] made the first genetically modified organism in 1973, a bacteria resistant to the antibiotic ]. The first ], a mouse, was created in 1974 by ], and the first plant was produced in 1983. In 1994 the ] tomato was released, the first commersialised ]. The first genetically modified animal to be commercialised was the ] (2003) and the first genetically modified animal to be approved for food use was ] in 2015. | |||

| Genetically engineered organism (GEO) can be considered a more precise term compared to GMO when describing organisms' genomes that have been directly manipulated with biotechnology.<ref>{{cite web|author=Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition|title=Food from Genetically Engineered Plants – Consumer Info About Food from Genetically Engineered Plants|url=https://www.fda.gov/food/ingredientspackaginglabeling/geplants/ucm461805.htm|access-date=8 January 2019|website=www.fda.gov}}</ref><ref name="Freedman-2018" /> The ] used the synonym ''living modified organism'' (''LMO'') in 2000 and defined it as "any living organism that possesses a novel combination of genetic material obtained through the use of modern biotechnology."<ref>Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Montreal: 2000. The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity.</ref> Modern biotechnology is further defined as "In vitro nucleic acid techniques, including ] (DNA) and direct injection of nucleic acid into cells or organelles, or fusion of cells beyond the taxonomic family."<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://bch.cbd.int/protocol/cpb_faq.shtml|title=Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the Cartagena Protocol|date=29 February 2012|website=The Biosafety Clearing-House (BCH)|access-date=3 January 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Bacteria are the easiest organisms to engineer and have been used for research, food production, industrial protein purification (including drugs), agriculture and art. There is potential to use them for environmental, purposes or as medicine. Fungi have been engineered with much the same goals. Viruses play an impotent role as ] for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This use is especially relevant to human ]. There are proposals to remove the ] properties from viruses and use them as vaccines. Plants have been engineered for scientific research, to create new colours in plants, deliver vaccines and to create enhanced crops. ] are publicly the most controversial GMOs. The majority are engineered for herbicide tolerance or insect resistance. ] has been engineered with three genes that increase its ]. Other prospects for GM crops are the production of ], biofuels or vaccines. | |||

| Originally, the term GMO was not commonly used by scientists to describe genetically engineered organisms until after usage of GMO became common in popular media.<ref name="NCState">{{cite web|url=https://agbiotech.ces.ncsu.edu/q1-what-is-the-difference-between-genetically-modified-organisms-and-genetically-engineered-organisms-we-seem-to-use-the-terms-interchangeably/|title=What Is the Difference Between Genetically Modified Organisms and Genetically Engineered Organisms?|website=agbiotech.ces.ncsu.edu|access-date=8 January 2019}}</ref> The ] (USDA) considers GMOs to be plants or animals with heritable changes introduced by genetic engineering or traditional methods, while GEO specifically refers to organisms with genes introduced, eliminated, or rearranged using molecular biology, particularly ] techniques, such as ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.usda.gov/topics/biotechnology/biotechnology-glossary|title=Agricultural Biotechnology Glossary {{!}} USDA|website=www.usda.gov|access-date=8 January 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Animals are generally much harder to transform and the vast majority are still at the research stage. Mammals are the best ] for human disease, making genetic engineered ones vital to the discovery and development of cures and treatments for many serious diseases. Human proteins expressed in mammals are more likely to be similar to their natural counterparts than those expressed in plants or microorganisms. Livestock are modified with the intention of improving economically important traits such as growth-rate, quality of meat, milk composition, disease resistance and survival. Although human gene therapy is still relatively new, it has been used to treat ] such as ], and ]. ] are used for scientific research, as pets and as a food source. Genetic engineering has been proposed as a way to control mosquitos, a ] for many deadly diseases. Other animals targeted by genetic engineering include silkworms, chickens and ]. | |||

| The definitions focus on the process more than the product, which means there could be GMOS and non-GMOs with very similar genotypes and phenotypes.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Colombo L | date=2007|title=The semantics of the term 'genetically modified organism' // Genetic impact of aquaculture activities on native populations.|journal=Genimpact Final Scientific Report (E U Contract N. RICA-CT -2005-022802)|pages=123–125}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Chassy BM |date=2007|title=The History and Future of GMOs in Food and Agriculture |journal=Cereal Foods World|doi=10.1094/cfw-52-4-0169|issn=0146-6283}}</ref> This has led scientists to label it as a scientifically meaningless category,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-11-03/why-term-gmo-scientifically-meaningless|title=Why the term GMO is 'scientifically meaningless'|website=Public Radio International|date=3 November 2014 |access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref> saying that it is impossible to group all the different types of GMOs under one common definition.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tagliabue G |title=The nonsensical GMO pseudo-category and a precautionary rabbit hole |journal=Nature Biotechnology |date=September 2015 |volume=33 |issue=9 |pages=907–908 |doi=10.1038/nbt.3333 |pmid=26348954 |s2cid=205281930 }}</ref> It has also caused issues for ] institutions and groups looking to ban GMOs.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/materialsky.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151002084810/http://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/materialsky.pdf |archive-date=2015-10-02 |url-status=live|title=National Organic Standards Board Materials/GMO Subcommittee Second Discussion Document on Excluded Methods Terminology |date=22 August 2014|website=United States Department of Agriculture|access-date=4 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://lostcoastoutpost.com/2014/oct/14/heres-why-you-should-vote-against-measure-p-even-i/|title=Here's Why You Should Vote Against Measure P, Even If You Hate GMOs|website=Lost Coast Outpost|access-date=4 January 2019}}</ref> It also poses problems as new processes are developed. The current definitions came in before ] became popular and there is some confusion as to whether they are GMOs. The EU has adjudged that they are<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/25/gene-editing-is-gm-europes-highest-court-rules|title=Gene-edited plants and animals are GM foods, EU court rules| vauthors = Neslen A |date=25 July 2018|work=The Guardian|access-date=5 January 2019|issn=0261-3077}}</ref> changing their GMO definition to include "organisms obtained by ]", but has excluded them from regulation based on their "long safety record" and that they have been "conventionally been used in a number of applications".<ref name=":17">{{Cite web|url=https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-07/cp180111en.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180725204750/https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2018-07/cp180111en.pdf |archive-date=2018-07-25 |url-status=live|title=Organisms obtained by mutagenesis are GMOs and are, in principle, subject to the obligations laid down by the GMO Directive|website=curia.europa.eu|access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref> In contrast the USDA has ruled that gene edited organisms are not considered GMOs.<ref name=":19" /> | |||

| Many objections have been raised over the development of GMO's, particularly their release into the environment. Many of these involve GM crops and whether food produced from them is safe and what impact growing them will have on the environment. Other concerns are the objectivity and rigor of regulatory authorities, contamination of non-genetically modified food, control of the ], ] and the use of ] rights. Although there is a ] that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, GM food safety is a leading issue with critics. ], impact on non-target organisms and escape are the major environmental concerns. Countries have adopted regulatory measures to deal with these concerns. There are differences in the regulation for the release of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the USA and Europe. One of the key issues concerning regulators is whether GM products should be labeled and the status of gene edited organisms. | |||

| Even greater inconsistency and confusion is associated with various "Non-GMO" or "GMO-free" labeling schemes in food marketing, where even products such as water or salt, which do not contain any organic substances and genetic material (and thus cannot be genetically modified by definition), are being labeled to create an impression of being "more healthy".<ref>{{Cite web|date=1 June 2018|title=Viewpoint: Non-GMO salt exploits Americans' scientific illiteracy|url=https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2018/06/01/viewpoint-non-gmo-salt-shows-americans-scientific-illiteracy/|access-date=9 July 2021|website=Genetic Literacy Project|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Knutson J | date = 28 May 2018 |title=A sad day for our society when salt is labeled non-GMO|url=https://www.agweek.com/opinion/columns/4451159-sad-day-our-society-when-salt-labeled-non-gmo|access-date=9 July 2021|website=Agweek|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=24 August 2015|title=Non GMO salt? Water? Food companies exploit GMO free labels, misleading customers, promoting misinformation|url=https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2015/08/24/non-gmo-salt-water-food-companies-exploit-gmo-free-labels-misleading-customers-promoting-misinformation/|access-date=9 July 2021|website=Genetic Literacy Project|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| <br />{{toclimit|3}} | |||

| ==Production== | == Production == | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Genetic engineering techniques}} | ||

| ] to insert DNA into plant tissue.|alt=]] | ] to insert DNA into plant tissue.|alt=]] | ||

| Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must |

Creating a genetically modified organism (GMO) is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must isolate the gene they wish to insert into the host organism. This gene can be taken from a ]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g1v6WMHVkTgC|title=An Introduction to Genetic Engineering| vauthors = Nicholl DS |date=29 May 2008|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-47178-7|pages=34 }}</ref> or ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Liang J, Luo Y, Zhao H | title = Synthetic biology: putting synthesis into biology | journal = Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine | volume = 3 | issue = 1 | pages = 7–20 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21064036 | pmc = 3057768 | doi = 10.1002/wsbm.104 }}</ref> If the chosen gene or the donor organism's ] has been well studied it may already be accessible from a ]. The gene is then combined with other genetic elements, including a ] and ] region and a ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Berg P, Mertz JE | title = Personal reflections on the origins and emergence of recombinant DNA technology | journal = Genetics | volume = 184 | issue = 1 | pages = 9–17 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 20061565 | pmc = 2815933 | doi = 10.1534/genetics.109.112144 }}</ref> | ||

| A number of techniques are available for ]. Bacteria can be induced to take up foreign DNA |

A number of techniques are available for ]. Bacteria can be induced to take up foreign DNA, usually by exposed ] or ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rahimzadeh M, Sadeghizadeh M, Najafi F, Arab S, Mobasheri H | title = Impact of heat shock step on bacterial transformation efficiency | journal = Molecular Biology Research Communications | volume = 5 | issue = 4 | pages = 257–261 | date = December 2016 | pmid = 28261629 | pmc = 5326489 }}</ref> DNA is generally inserted into animal cells using ], where it can be injected through the cell's ] directly into the ], or through the use of ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen I, Dubnau D | title = DNA uptake during bacterial transformation | journal = Nature Reviews. Microbiology | volume = 2 | issue = 3 | pages = 241–9 | date = March 2004 | pmid = 15083159 | doi = 10.1038/nrmicro844 | s2cid = 205499369 }}</ref> In plants the DNA is often inserted using ],<ref name="NRC_GMO_Foods">{{cite book|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215771/|title=Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms| author = National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health |date=1 January 2004|publisher=National Academies Press (US)}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gelvin SB | title = Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the 'gene-jockeying' tool | journal = Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews | volume = 67 | issue = 1 | pages = 16–37, table of contents | date = March 2003 | pmid = 12626681 | pmc = 150518 | doi = 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.16-37.2003 }}</ref> ]<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Head G, Hull RH, Tzotzos GT |title= Genetically Modified Plants: Assessing Safety and Managing Risk |publisher=Academic Press |location=London |year=2009 |page=244 |isbn=978-0-12-374106-6 }}</ref> or electroporation. | ||

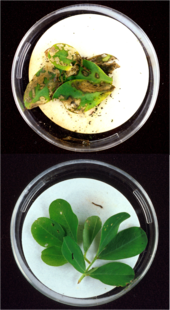

| As only a single cell is transformed with genetic material, the organism must be ] from that single cell. In plants this is accomplished through ]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tuomela M, Stanescu I, Krohn K | title = Validation overview of bio-analytical methods | journal = Gene Therapy | volume = 12 |

As only a single cell is transformed with genetic material, the organism must be ] from that single cell. In plants this is accomplished through ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tuomela M, Stanescu I, Krohn K | title = Validation overview of bio-analytical methods | journal = Gene Therapy | volume = 12 | issue = S1 | pages = S131-8 | date = October 2005 | pmid = 16231045 | doi = 10.1038/sj.gt.3302627 | s2cid = 23000818 | doi-access = }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-M4lR-pxqJMC|title=Plant Cell and Tissue Culture| vauthors = Narayanaswamy S |date=1994|publisher=Tata McGraw-Hill Education|isbn=978-0-07-460277-5|pages=vi}}</ref> In animals it is necessary to ensure that the inserted DNA is present in the ].<ref name="NRC_GMO_Foods" /> Further testing using ], ], and ] is conducted to confirm that an organism contains the new gene.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aGkXFmqOcyIC&q=Genetic+Engineering+analysis+of+DNA+PCR+Southern+sequencing|title=Genetic Engineering: Principles and Methods| vauthors = Setlow JK |date=31 October 2002|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-306-47280-0|pages=109 }}</ref> | ||

| Traditionally the new genetic material was inserted randomly within the host genome. ] techniques, which creates ] and takes advantage on the cells natural ] repair systems, have been developed to target insertion to exact ]. ] uses artificially engineered ]s that create breaks at specific points. There are four families of engineered nucleases: ]s,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, Villate M, Thomas S, Lemaire L, Montoya G, Blanco FJ, Pâques F, Duchateau P | title = Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease | journal = Nucleic Acids Research | volume = 37 | issue = 16 | pages = 5405–19 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 19584299 | pmc = 2760784 | doi = 10.1093/nar/gkp548 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D, Lyznik LA | title = Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease | journal = The Plant Journal | volume = 61 | issue = 1 | pages = 176–87 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 19811621 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x }}</ref> ]s,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF | title = High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases | journal = Nature | volume = 459 | issue = 7245 | pages = 442–5 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 19404258 | pmc = 2743854 | doi = 10.1038/nature07845 | bibcode = 2009Natur.459..442T }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD | title = Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases | journal = Nature | volume = 459 | issue = 7245 | pages = 437–41 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 19404259 | doi = 10.1038/nature07992 | bibcode = 2009Natur.459..437S }}</ref> ]s (TALENs),<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF | title = Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases | journal = Genetics | volume = 186 | issue = 2 | pages = 757–61 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20660643 | pmc = 2942870 | doi = 10.1534/genetics.110.120717 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Li T, Huang S, Jiang WZ, Wright D, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B | title = TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain | journal = Nucleic Acids Research | volume = 39 | issue = 1 | pages = 359–72 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 20699274 | pmc = 3017587 | doi = 10.1093/nar/gkq704 }}</ref> and the Cas9-guideRNA system (adapted from CRISPR).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Esvelt KM, Wang HH | title = Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology | journal = Molecular Systems Biology | volume = 9 |

Traditionally the new genetic material was inserted randomly within the host genome. ] techniques, which creates ] and takes advantage on the cells natural ] repair systems, have been developed to target insertion to exact ]. ] uses artificially engineered ]s that create breaks at specific points. There are four families of engineered nucleases: ]s,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, Villate M, Thomas S, Lemaire L, Montoya G, Blanco FJ, Pâques F, Duchateau P | title = Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease | journal = Nucleic Acids Research | volume = 37 | issue = 16 | pages = 5405–19 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 19584299 | pmc = 2760784 | doi = 10.1093/nar/gkp548 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D, Lyznik LA | title = Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease | journal = The Plant Journal | volume = 61 | issue = 1 | pages = 176–87 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 19811621 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x | doi-access = }}</ref> ]s,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF | title = High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases | journal = Nature | volume = 459 | issue = 7245 | pages = 442–5 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 19404258 | pmc = 2743854 | doi = 10.1038/nature07845 | bibcode = 2009Natur.459..442T }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD | title = Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases | journal = Nature | volume = 459 | issue = 7245 | pages = 437–41 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 19404259 | doi = 10.1038/nature07992 | bibcode = 2009Natur.459..437S | s2cid = 4323298 }}</ref> ]s (TALENs),<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF | title = Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases | journal = Genetics | volume = 186 | issue = 2 | pages = 757–61 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20660643 | pmc = 2942870 | doi = 10.1534/genetics.110.120717 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Li T, Huang S, Jiang WZ, Wright D, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B | title = TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain | journal = Nucleic Acids Research | volume = 39 | issue = 1 | pages = 359–72 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 20699274 | pmc = 3017587 | doi = 10.1093/nar/gkq704 }}</ref> and the Cas9-guideRNA system (adapted from CRISPR).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Esvelt KM, Wang HH | title = Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology | journal = Molecular Systems Biology | volume = 9 | pages = 641 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23340847 | pmc = 3564264 | doi = 10.1038/msb.2012.66 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Tan WS, Carlson DF, Walton MW, Fahrenkrug SC, Hackett PB | title = Advances in Genetics Volume 80 | chapter = Precision editing of large animal genomes | volume = 80 | pages = 37–97 | year = 2012 | pmid = 23084873 | pmc = 3683964 | doi = 10.1016/B978-0-12-404742-6.00002-8 | isbn = 978-0-12-404742-6 }}</ref> TALEN and CRISPR are the two most commonly used and each has its own advantages.<ref name=":5">{{cite journal | vauthors = Malzahn A, Lowder L, Qi Y | title = Plant genome editing with TALEN and CRISPR | journal = Cell & Bioscience | volume = 7 | pages = 21 | date = 24 April 2017 | pmid = 28451378 | pmc = 5404292 | doi = 10.1186/s13578-017-0148-4 | doi-access = free }}</ref> TALENs have greater target specificity, while CRISPR is easier to design and more efficient.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

| ==History== | == History == | ||

| {{Main|History of genetic engineering}} | {{Main|History of genetic engineering}} | ||

| ] (pictured) and ] created the first genetically modified organism in 1973.]] | ] (pictured) and ] created the first genetically modified organism in 1973.]] | ||

| Humans have ] plants and animals since around 12,000 BCE, using ] or artificial selection (as contrasted with ]).<ref name=Kingsbury> |

Humans have ] plants and animals since around 12,000 BCE, using ] or artificial selection (as contrasted with ]).<ref name=Kingsbury>{{cite book | vauthors = Kingsbury N |title=Hybrid: The History and Science of Plant Breeding |date=2009 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-43705-7 }}</ref>{{rp|25}} The process of ], in which organisms with desired ] (and thus with the desired ]) are used to breed the next generation and organisms lacking the trait are not bred, is a precursor to the modern concept of genetic modification.<ref name=Root>{{cite book|title=Domestication|url={{google books|plainurl=y|id=WGDYHvOHwmwC|p=1}}|author=Clive Root|year=2007|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Groups}}</ref>{{rp|1}}<ref name=Zohary>{{cite book |title=Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Plants in the Old World|url= {{google books|plainurl=y|id=tc6vr0qzk_4C|p=1}}| vauthors = Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E |year=2012|publisher= Oxford University Press}}</ref>{{rp|1}} Various advancements in ] allowed humans to directly alter the DNA and therefore genes of organisms. In 1972, ] created the first ] molecule when he combined DNA from a monkey virus with that of the ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jackson DA, Symons RH, Berg P | title = Biochemical method for inserting new genetic information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 69 | issue = 10 | pages = 2904–9 | date = October 1972 | pmid = 4342968 | pmc = 389671 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.69.10.2904 | bibcode = 1972PNAS...69.2904J | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Sateesh2008">{{cite book| vauthors = Sateesh MK |title=Bioethics And Biosafety|url={{google books|plainurl=y|id=xP9dzbSBTZQC|p=456}}|access-date=27 March 2013|date=25 August 2008|publisher=I. K. International Pvt Ltd|isbn=978-81-906757-0-3|pages=456–}}</ref> | ||

| ] and ] made the first genetically modified organism in 1973. They took a gene from a bacterium that provided resistance to the antibiotic ], inserted it into a ] and then induced |

] and ] made the first genetically modified organism in 1973.<ref>{{Cite journal | vauthors = Zhang C, Wohlhueter R, Zhang H |date=2016 |title=Genetically modified foods: A critical review of their promise and problems |journal=Food Science and Human Wellness |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=116–123 |doi=10.1016/j.fshw.2016.04.002 |doi-access=free }}</ref> They took a gene from a bacterium that provided resistance to the antibiotic ], inserted it into a ] and then induced other bacteria to incorporate the plasmid. The bacteria that had successfully incorporated the plasmid was then able to survive in the presence of kanamycin.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Russo E | title = The birth of biotechnology | journal = Nature | volume = 421 | issue = 6921 | pages = 456–7 | date = January 2003 | pmid = 12540923 | doi = 10.1038/nj6921-456a | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2003Natur.421..456R }}</ref> Boyer and Cohen expressed other genes in bacteria. This included genes from the toad '']'' in 1974, creating the first GMO expressing a gene from an organism of a different ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Morrow JF, Cohen SN, Chang AC, Boyer HW, Goodman HM, Helling RB | title = Replication and transcription of eukaryotic DNA in Escherichia coli | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 71 | issue = 5 | pages = 1743–7 | date = May 1974 | pmid = 4600264 | pmc = 388315 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1743 | bibcode = 1974PNAS...71.1743M | doi-access = free }}</ref> | ||

| ] created the first |

] created the first genetically modified animal.]] | ||

| In 1974 ] created a ] by introducing foreign DNA into its embryo, making it the |

In 1974, ] created a ] by introducing foreign DNA into its embryo, making it the world's first transgenic animal.<ref name="Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DN">{{cite journal | vauthors = Jaenisch R, Mintz B | title = Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DNA of healthy adult mice derived from preimplantation blastocysts injected with viral DNA | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 71 | issue = 4 | pages = 1250–4 | date = April 1974 | pmid = 4364530 | pmc = 388203 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250 | bibcode = 1974PNAS...71.1250J | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.science.org/content/article/any-idiot-can-do-it-genome-editor-crispr-could-put-mutant-mice-everyones-reach|title='Any idiot can do it.' Genome editor CRISPR could put mutant mice in everyone's reach|date=2 November 2016|newspaper=Science {{!}} AAAS|access-date=2 December 2016}}</ref> However it took another eight years before transgenic mice were developed that passed the ] to their offspring.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gordon JW, Ruddle FH | title = Integration and stable germ line transmission of genes injected into mouse pronuclei | journal = Science | volume = 214 | issue = 4526 | pages = 1244–6 | date = December 1981 | pmid = 6272397 | doi = 10.1126/science.6272397 | bibcode = 1981Sci...214.1244G }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Costantini F, Lacy E | title = Introduction of a rabbit beta-globin gene into the mouse germ line | journal = Nature | volume = 294 | issue = 5836 | pages = 92–4 | date = November 1981 | pmid = 6945481 | doi = 10.1038/294092a0 | bibcode = 1981Natur.294...92C | s2cid = 4371351 }}</ref> Genetically modified mice were created in 1984 that carried cloned ], predisposing them to developing cancer.<ref name =Hanahan>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hanahan D, Wagner EF, Palmiter RD | title = The origins of oncomice: a history of the first transgenic mice genetically engineered to develop cancer | journal = Genes & Development | volume = 21 | issue = 18 | pages = 2258–70 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17875663 | doi = 10.1101/gad.1583307 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Mice with ] (termed a ]) were created in 1989. The first transgenic livestock were produced in 1985<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Brophy B, Smolenski G, Wheeler T, Wells D, L'Huillier P, Laible G | title = Cloned transgenic cattle produce milk with higher levels of beta-casein and kappa-casein | journal = Nature Biotechnology | volume = 21 | issue = 2 | pages = 157–62 | date = February 2003 | pmid = 12548290 | doi = 10.1038/nbt783 | s2cid = 45925486 }}</ref> and the first animal to synthesize transgenic proteins in their milk were mice in 1987.<ref name="Clark">{{cite journal | vauthors = Clark AJ | title = The mammary gland as a bioreactor: expression, processing, and production of recombinant proteins | journal = Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia | volume = 3 | issue = 3 | pages = 337–50 | date = July 1998 | pmid = 10819519 | doi = 10.1023/a:1018723712996 }}</ref> The mice were engineered to produce human ], a protein involved in breaking down ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gordon K, Lee E, Vitale JA, Smith AE, Westphal H, Hennighausen L | title = Production of human tissue plasminogen activator in transgenic mouse milk. 1987 | journal = Biotechnology | volume = 24 | issue = 11 | pages = 425–8 | year = 1987 | pmid = 1422049 | doi = 10.1038/nbt1187-1183 | s2cid = 3261903 | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1233349 }}</ref> | ||

| In 1983 the first ] was developed by ], ] and ]. They infected tobacco with '']'' ] with an antibiotic resistance gene and through ] techniques were able to grow a new plant containing the resistance gene.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bevan MW, Flavell RB, Chilton MD | title = A chimaeric antibiotic resistance gene as a selectable marker for plant cell transformation. 1983 | journal = |

In 1983, the first ] was developed by ], ] and ]. They infected tobacco with '']'' ] with an antibiotic resistance gene and through ] techniques were able to grow a new plant containing the resistance gene.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bevan MW, Flavell RB, Chilton MD | title = A chimaeric antibiotic resistance gene as a selectable marker for plant cell transformation. 1983 | journal = Nature | volume = 304 | issue = 5922 | pages = 184 | year = 1983 | doi = 10.1038/304184a0 | bibcode = 1983Natur.304..184B | s2cid = 28713537 | author-link1 = Michael W. Bevan | author-link3 = Mary-Dell Chilton }}</ref> The ] was invented in 1987, allowing transformation of plants not susceptible to ''Agrobacterium'' infection.<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1016/b978-0-12-384964-9.00003-7 |chapter=Gene Delivery Using Physical Methods |title=Challenges in Delivery of Therapeutic Genomics and Proteomics |pages=83–126 |year=2011 | vauthors = Jinturkar KA, Rathi MN, Misra A |isbn=978-0-12-384964-9 }}</ref> In 2000, ]-enriched ] was the first plant developed with increased nutrient value.<ref name="ye2000" /> | ||

| In 1976 ], the first genetic engineering company was founded by Herbert Boyer and ]; a year later, the company produced a human protein (]) in '']''. Genentech announced the production of genetically engineered human ] in 1978.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goeddel DV, Kleid DG, Bolivar F, Heyneker HL, Yansura DG, Crea R, Hirose T, Kraszewski A, Itakura K, Riggs AD | title = Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 76 | issue = 1 | pages = 106–10 | date = January 1979 | pmid = 85300 | pmc = 382885 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.76.1.106 | bibcode = 1979PNAS...76..106G }}</ref> The insulin produced by bacteria, branded ], was approved for release by the ] in 1982.<ref>{{cite |

In 1976, ], the first genetic engineering company was founded by Herbert Boyer and ]; a year later, the company produced a human protein (]) in '']''. Genentech announced the production of genetically engineered human ] in 1978.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goeddel DV, Kleid DG, Bolivar F, Heyneker HL, Yansura DG, Crea R, Hirose T, Kraszewski A, Itakura K, Riggs AD | title = Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 76 | issue = 1 | pages = 106–10 | date = January 1979 | pmid = 85300 | pmc = 382885 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.76.1.106 | bibcode = 1979PNAS...76..106G | doi-access = free }}</ref> The insulin produced by bacteria, branded ], was approved for release by the ] in 1982.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,949646-1,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027011602/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,949646-1,00.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=27 October 2011 |title=Artificial Genes |magazine=] |date=15 November 1982 |access-date=17 July 2010}}</ref> In 1988, the first human antibodies were produced in plants.<ref name="antibodies">{{cite journal | vauthors = Horn ME, Woodard SL, Howard JA | title = Plant molecular farming: systems and products | journal = Plant Cell Reports | volume = 22 | issue = 10 | pages = 711–20 | date = May 2004 | pmid = 14997337 | pmc =7079917 | doi = 10.1007/s00299-004-0767-1 }}</ref> In 1987, a strain of '']'' became the first genetically modified organism to be released into the environment<ref name="BBC2002">BBC News 14 June 2002 </ref> when a strawberry and potato field in California were sprayed with it.<ref>{{cite news |last=Maugh |first=Thomas H. II |date=9 June 1987 |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-06-09-mn-6024-story.html |title=Altered Bacterium Does Its Job: Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says |work=]}}</ref> | ||

| The first ], an antibiotic-resistant tobacco plant, was produced in 1982.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fraley RT, Rogers SG, Horsch RB, Sanders PR, Flick JS, Adams SP, Bittner ML, Brand LA, Fink CL, Fry JS, Galluppi GR, Goldberg SB, Hoffmann NL, Woo SC | title = Expression of bacterial genes in plant cells | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 80 | issue = 15 | pages = 4803–7 | date = August 1983 | pmid = 6308651 | pmc = 384133 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4803 | bibcode = 1983PNAS...80.4803F | |

The first ], an antibiotic-resistant tobacco plant, was produced in 1982.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fraley RT, Rogers SG, Horsch RB, Sanders PR, Flick JS, Adams SP, Bittner ML, Brand LA, Fink CL, Fry JS, Galluppi GR, Goldberg SB, Hoffmann NL, Woo SC | title = Expression of bacterial genes in plant cells | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 80 | issue = 15 | pages = 4803–7 | date = August 1983 | pmid = 6308651 | pmc = 384133 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4803 | bibcode = 1983PNAS...80.4803F | doi-access = free }}</ref> China was the first country to commercialize transgenic plants, introducing a virus-resistant tobacco in 1992.<ref name="James1997">{{cite journal|author=James, Clive|year=1997|title=Global Status of Transgenic Crops in 1997|journal=ISAAA Briefs No. 5.|page=31|url=http://www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/briefs/05/download/isaaa-brief-05-1997.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090116155014/http://www.isaaa.org/Resources/Publications/briefs/05/download/isaaa-brief-05-1997.pdf |archive-date=2009-01-16 |url-status=live}}</ref> In 1994, ] attained approval to commercially release the ] tomato, the first ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bruening G, Lyons JM | year = 2000 | title = The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato | journal = California Agriculture | volume = 54 | issue = 4 | pages = 6–7 | url = http://ucanr.org/repository/CAO/landingpage.cfm?article=ca.v054n04p6&fulltext=yes | doi=10.3733/ca.v054n04p6| doi-broken-date = 1 November 2024 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Also in 1994, the European Union approved tobacco engineered to be resistant to the herbicide ], making it the first genetically engineered crop commercialized in Europe.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=Transgenic tobacco is European first|date=18 June 1994|author=Debora MacKenzie|url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg14219301.100-transgenic-tobacco-is-european-first.html|magazine=]}}</ref> An insect resistant Potato was approved for release in the US in 1995,<ref> Lawrence Journal-World. 6 May 1995</ref> and by 1996 approval had been granted to commercially grow 8 transgenic crops and one flower crop (carnation) in 6 countries plus the EU.<ref name="James 1996">{{cite web| vauthors = James C |title=Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995|url=http://www.isaaa.org/kc/Publications/pdfs/isaaabriefs/Briefs%201.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100616175626/http://isaaa.org/kc/Publications/pdfs/isaaabriefs/Briefs%201.pdf |archive-date=2010-06-16 |url-status=live|publisher=The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications|access-date=17 July 2010|year=1996}}</ref> | ||

| In 2010, scientists at the ] |

In 2010, scientists at the ] announced that they had created the first synthetic bacterial ]. They named it ] and it was the world's first ] form.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, Benders GA, Montague MG, Ma L, Moodie MM, Merryman C, Vashee S, Krishnakumar R, Assad-Garcia N, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Denisova EA, Young L, Qi ZQ, Segall-Shapiro TH, Calvey CH, Parmar PP, Hutchison CA, Smith HO, Venter JC | title = Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome | journal = Science | volume = 329 | issue = 5987 | pages = 52–6 | date = July 2010 | pmid = 20488990 | doi = 10.1126/science.1190719 | bibcode = 2010Sci...329...52G | s2cid = 7320517 | doi-access = }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Craig Venter creates synthetic life form | vauthors = Sample I |work=guardian.co.uk |date=20 May 2010 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2010/may/20/craig-venter-synthetic-life-form |location=London}}</ref> | ||

| The first genetically modified animal to be |

The first genetically modified animal to be commercialized was the ], a ] with a ] added that allows it to glow in the dark under ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vàzquez-Salat N, Salter B, Smets G, Houdebine LM | title = The current state of GMO governance: are we ready for GM animals? | journal = Biotechnology Advances | volume = 30 | issue = 6 | pages = 1336–43 | date = 1 November 2012 | pmid = 22361646 | doi = 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.02.006 | series = Special issue on ACB 2011 }}</ref> It was released to the US market in 2003.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://edition.cnn.com/2003/US/11/21/offbeat.glofish.reut/|title=Glowing fish to be first genetically changed pet|date=21 November 2003|publisher=CNN|access-date=25 December 2018|archive-date=25 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181225130006/http://edition.cnn.com/2003/US/11/21/offbeat.glofish.reut/|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2015, ] became the first genetically modified animal to be approved for food use.<ref name=":20">{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/20/business/genetically-engineered-salmon-approved-for-consumption.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220102/https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/20/business/genetically-engineered-salmon-approved-for-consumption.html |archive-date=2 January 2022 |url-access=limited |url-status=live|title=Genetically Engineered Salmon Approved for Consumption| vauthors = Pollack A |date=19 November 2015|work=]|access-date=27 January 2019|issn=0362-4331}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Approval is for fish raised in Panama and sold in the US.<ref name=":20" /> The salmon were transformed with a ]-regulating gene from a ] and a promoter from an ] enabling it to grow year-round instead of only during spring and summer.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.aquabounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Risk_Assessment_Mitigation_of_AAS-Oct2010.pdf|title = Risk Assessment and Mitigation of AquAdvantage Salmon|date = October 2010|publisher = ISB News Report|vauthors = Bodnar A|access-date = 22 January 2016|archive-date = 8 March 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210308125138/https://aquabounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Risk_Assessment_Mitigation_of_AAS-Oct2010.pdf|url-status = dead}}</ref> | ||

| == Bacteria == | == Bacteria == | ||

| Line 52: | Line 64: | ||

| | align = right | | align = right | ||

| | footer = '''Left:''' Bacteria transformed with ] under ambient light<br /> | | footer = '''Left:''' Bacteria transformed with ] under ambient light<br /> | ||

| '''Right:''' Bacteria transformed with pGLO |

'''Right:''' Bacteria transformed with pGLO visualized under ultraviolet light | ||

| | image1 = |

| image1 = PLGO under ambient light.jpg | ||

| | width1 = 180 | | width1 = 180 | ||

| | image2 = PGlo-UltraViolet.jpg | | image2 = PGlo-UltraViolet.jpg | ||

| Line 59: | Line 71: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] were the first organisms to be genetically modified in the laboratory, due to the relative ease of modifying their chromosomes.<ref name="Melo">{{cite journal | vauthors = Melo EO, Canavessi AM, Franco MM, Rumpf R | title = Animal transgenesis: state of the art and applications | journal = Journal of Applied Genetics | volume = 48 | issue = 1 | pages = 47–61 | |

] were the first organisms to be genetically modified in the laboratory, due to the relative ease of modifying their chromosomes.<ref name="Melo">{{cite journal | vauthors = Melo EO, Canavessi AM, Franco MM, Rumpf R | title = Animal transgenesis: state of the art and applications | journal = Journal of Applied Genetics | volume = 48 | issue = 1 | pages = 47–61 | date = March 2007 | pmid = 17272861 | doi = 10.1007/BF03194657 | s2cid = 24578435 | url = http://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/156019/1/art3A10.10072FBF03194657.pdf }}</ref> This ease made them important tools for the creation of other GMOs. Genes and other genetic information from a wide range of organisms can be added to a ] and inserted into bacteria for storage and modification. Bacteria are cheap, easy to grow, ], multiply quickly and can be stored at −80 °C almost indefinitely. Once a gene is isolated it can be stored inside the bacteria, providing an unlimited supply for research.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.learner.org/courses/biology/textbook/gmo/gmo_2.html|title=Rediscovering Biology – Online Textbook: Unit 13 Genetically Modified Organisms|website=www.learner.org|access-date=18 August 2017|archive-date=3 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191203123559/http://www.learner.org/courses/biology/textbook/gmo/gmo_2.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> A large number of custom plasmids make manipulating DNA extracted from bacteria relatively easy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fan M, Tsai J, Chen B, Fan K, LaBaer J | title = A central repository for published plasmids | journal = Science | volume = 307 | issue = 5717 | pages = 1877 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15790830 | doi = 10.1126/science.307.5717.1877a | s2cid = 27404861 }}</ref> | ||

| Their ease of use has made them great tools for scientists looking to study gene function and ]. |

Their ease of use has made them great tools for scientists looking to study gene function and ]. The simplest ]s come from bacteria, with most of our early understanding of ] coming from studying '']''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cooper GM |date=2000|title=Cells As Experimental Models|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9917/|journal=The Cell: A Molecular Approach |edition=2nd}}</ref> Scientists can easily manipulate and combine genes within the bacteria to create novel or disrupted proteins and observe the effect this has on various molecular systems. Researchers have combined the genes from bacteria and ], leading to insights on how these two diverged in the past.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Patel P | title = Microbe Mystery | journal = ] | volume = 319 | issue = 1 | pages = 18 | date = June 2018 | pmid = 29924081 | doi = 10.1038/scientificamerican0718-18a | bibcode = 2018SciAm.319a..18P | s2cid = 49310760 }}</ref> In the field of ], they have been used to test various synthetic approaches, from synthesizing genomes to creating novel ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Arpino JA, Hancock EJ, Anderson J, Barahona M, Stan GB, Papachristodoulou A, Polizzi K | title = Tuning the dials of Synthetic Biology | journal = Microbiology | volume = 159 | issue = Pt 7 | pages = 1236–53 | date = July 2013 | pmid = 23704788 | pmc = 3749727 | doi = 10.1099/mic.0.067975-0 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="NYT-20140507">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/business/researchers-report-breakthrough-in-creating-artificial-genetic-code.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220102/https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/business/researchers-report-breakthrough-in-creating-artificial-genetic-code.html |archive-date=2 January 2022 |url-access=limited |url-status=live|title=Researchers Report Breakthrough in Creating Artificial Genetic Code| vauthors = Pollack A |date=7 May 2014|work=The New York Times|access-date=7 May 2014}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name="NATJ-20140507">{{cite journal | vauthors = Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, Corrêa IR, Romesberg FE | title = A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet | journal = Nature | volume = 509 | issue = 7500 | pages = 385–8 | date = May 2014 | pmid = 24805238 | pmc = 4058825 | doi = 10.1038/nature13314 | bibcode = 2014Natur.509..385M }}</ref> | ||

| Bacteria have been used in the production of food for a long time, and specific strains have been developed and selected for that work on an ] scale. They can be used to produce ]s, ]s, ], and other compounds used in food production. With the advent of genetic engineering, new genetic changes can easily be introduced into these bacteria. Most food-producing bacteria are ], and this is where the majority of research into genetically engineering food-producing bacteria has gone. The bacteria can be modified to operate more efficiently, reduce toxic byproduct production, increase output, create improved compounds, and remove unnecessary ].<ref name=":2">{{cite book|date=2016- |

Bacteria have been used in the production of food for a long time, and specific strains have been developed and selected for that work on an ] scale. They can be used to produce ]s, ]s, ]s, and other compounds used in food production. With the advent of genetic engineering, new genetic changes can easily be introduced into these bacteria. Most food-producing bacteria are ], and this is where the majority of research into genetically engineering food-producing bacteria has gone. The bacteria can be modified to operate more efficiently, reduce toxic byproduct production, increase output, create improved compounds, and remove unnecessary ].<ref name=":2">{{cite book|chapter=Genetically Modified Microorganisms|vauthors=Kärenlampi SO, von Wright AJ|title=Encyclopedia of Food and Health |date=1 January 2016|publisher=Encyclopedia of Food and Health|isbn=978-0-12-384953-3|pages=211–216|doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00356-1}}</ref> Food products from genetically modified bacteria include ], which converts starch to simple sugars, ], which clots milk protein for cheese making, and ], which improves fruit juice clarity.<ref>Panesar, Pamit et al. (2010) ''Enzymes in Food Processing: Fundamentals and Potential Applications'', Chapter 10, I K International Publishing House, {{ISBN|978-93-80026-33-6}}</ref> The majority are produced in the US and even though regulations are in place to allow production in Europe, as of 2015 no food products derived from bacteria are currently available there.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Genetic Modification and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis| vauthors = Blair R, Regenstein JM |date=3 August 2015|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-118-75641-6|pages=20–24}}</ref> | ||

| Genetically modified bacteria are used to produce large amounts of proteins for industrial use. |

Genetically modified bacteria are used to produce large amounts of proteins for industrial use. The bacteria are generally grown to a large volume before the gene encoding the protein is activated. The bacteria are then harvested and the desired protein purified from them.<ref name=":3">{{cite book |title=Genetically Modified Organisms the Mystery Unraveled| vauthors = Jumba M |publisher=Eloquent Books|year=2009|isbn=978-1-60911-081-9|location=Durham|pages=51–54 }}</ref> The high cost of extraction and purification has meant that only high value products have been produced at an industrial scale.<ref name=":4">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhou Y, Lu Z, Wang X, Selvaraj JN, Zhang G | title = Genetic engineering modification and fermentation optimization for extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli | journal = Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology | volume = 102 | issue = 4 | pages = 1545–1556 | date = February 2018 | pmid = 29270732 | doi = 10.1007/s00253-017-8700-z | s2cid = 253769838 }}</ref> The majority of these products are human proteins for use in medicine.<ref name="Leader2008">{{cite journal | vauthors = Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE | title = Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification | journal = Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 21–39 | date = January 2008 | pmid = 18097458 | doi = 10.1038/nrd2399 | series = A guide to drug discovery | s2cid = 3358528 }}</ref> Many of these proteins are impossible or difficult to obtain via natural methods and they are less likely to be contaminated with pathogens, making them safer.<ref name=":3" /> The first medicinal use of GM bacteria was to produce the protein ] to treat ].<ref name="Walsh2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Walsh G | title = Therapeutic insulins and their large-scale manufacture | journal = Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology | volume = 67 | issue = 2 | pages = 151–9 | date = April 2005 | pmid = 15580495 | doi = 10.1007/s00253-004-1809-x | s2cid = 5986035 }}</ref> Other medicines produced include ] to treat ],<ref name="Pipe2008">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pipe SW | title = Recombinant clotting factors | journal = Thrombosis and Haemostasis | volume = 99 | issue = 5 | pages = 840–50 | date = May 2008 | pmid = 18449413 | doi = 10.1160/TH07-10-0593 | s2cid = 2701961 }}</ref> ] to treat various forms of ],<ref name="Bryant2007">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bryant J, Baxter L, Cave CB, Milne R | title = Recombinant growth hormone for idiopathic short stature in children and adolescents | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 3 | pages = CD004440 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17636758 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD004440.pub2 | veditors = Bryant J | url = https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/1236226/1/Bryant_et_al-2007-The_Cochrane_library.pdf }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Baxter L, Bryant J, Cave CB, Milne R | title = Recombinant growth hormone for children and adolescents with Turner syndrome | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 1 | pages = CD003887 | date = January 2007 | pmid = 17253498 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD003887.pub2 | veditors = Bryant J | url = https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/1236240/1/Baxter_et_al-2007-The_Cochrane_library.pdf }}</ref> ] to treat some cancers, ] for anemic patients, and ] which dissolves blood clots.<ref name=":3" /> Outside of medicine they have been used to produce ]s.<ref>Summers, Rebecca (24 April 2013). . ''New Scientist'', Retrieved 27 April 2013</ref> There is interest in developing an extracellular expression system within the bacteria to reduce costs and make the production of more products economical.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

| With greater understanding of the role that the ] plays in human health, there is |

With a greater understanding of the role that the ] plays in human health, there is a potential to treat diseases by genetically altering the bacteria to, themselves, be therapeutic agents. Ideas include altering gut bacteria so they destroy harmful bacteria, or using bacteria to replace or increase deficient ] or proteins. One research focus is to modify '']'', bacteria that naturally provide some protection against ], with genes that will further enhance this protection. If the bacteria do not form ] inside the patient, the person must repeatedly ingest the modified bacteria in order to get the required doses. Enabling the bacteria to form a colony could provide a more long-term solution, but could also raise safety concerns as interactions between bacteria and the human body are less well understood than with traditional drugs. There are concerns that ] to other bacteria could have unknown effects. As of 2018 there are clinical trials underway testing the ] and safety of these treatments.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Reardon S | title = Genetically modified bacteria enlisted in fight against disease | journal = Nature | volume = 558 | issue = 7711 | pages = 497–498 | date = June 2018 | pmid = 29946090 | doi = 10.1038/d41586-018-05476-4 | bibcode = 2018Natur.558..497R | doi-access = free }}</ref> | ||

| For over a century bacteria have been used in agriculture. Crops have been ] with ] (and more recently '']'') to increase their production or to allow them to be grown outside their original ]. Application of '']'' (Bt) and other bacteria can help protect crops from insect infestation and plant diseases. With advances in genetic engineering, these bacteria have been manipulated for increased efficiency and expanded host range. Markers have also been added to aid in tracing the spread of the bacteria. The bacteria that naturally |

For over a century, bacteria have been used in agriculture. Crops have been ] with ] (and more recently '']'') to increase their production or to allow them to be grown outside their original ]. Application of '']'' (Bt) and other bacteria can help protect crops from insect infestation and plant diseases. With advances in genetic engineering, these bacteria have been manipulated for increased efficiency and expanded host range. Markers have also been added to aid in tracing the spread of the bacteria. The bacteria that naturally colonize certain crops have also been modified, in some cases to express the Bt genes responsible for pest resistance. '']'' strains of bacteria cause frost damage by ] water into ] around themselves. This led to the development of ], which have the ice-forming genes removed. When applied to crops they can compete with the non-modified bacteria and confer some frost resistance.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Amarger N | title = Genetically modified bacteria in agriculture | journal = Biochimie | volume = 84 | issue = 11 | pages = 1061–72 | date = November 2002 | pmid = 12595134 | doi = 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)00035-4 }}</ref> | ||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include ], where the bacteria are used to convert pollutants into a less toxic form. Genetic engineering can increase the levels of the enzymes used to degrade a toxin or to make the bacteria more stable under environmental conditions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sharma B, Dangi AK, Shukla P | title = Contemporary enzyme based technologies for bioremediation: A review | journal = Journal of Environmental Management | volume = 210 | pages = 10–22 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29329004 | doi = 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.075 }}</ref> ] has also been created using genetically modified bacteria. In the 1980s artist ] and geneticist ] converted the Germanic symbol for femininity (ᛉ) into binary code and then into a DNA sequence, which was then expressed in '']''.<ref name=":6">{{cite journal | vauthors = Yetisen AK, Davis J, Coskun AF, Church GM, Yun SH | title = Bioart |

Other uses for genetically modified bacteria include ], where the bacteria are used to convert pollutants into a less toxic form. Genetic engineering can increase the levels of the enzymes used to degrade a toxin or to make the bacteria more stable under environmental conditions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sharma B, Dangi AK, Shukla P | title = Contemporary enzyme based technologies for bioremediation: A review | journal = Journal of Environmental Management | volume = 210 | pages = 10–22 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29329004 | doi = 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.075 | bibcode = 2018JEnvM.210...10S }}</ref> ] has also been created using genetically modified bacteria. In the 1980s artist ] and geneticist ] converted the Germanic symbol for femininity (ᛉ) into binary code and then into a DNA sequence, which was then expressed in '']''.<ref name=":6">{{cite journal | vauthors = Yetisen AK, Davis J, Coskun AF, Church GM, Yun SH | title = Bioart | journal = Trends in Biotechnology | volume = 33 | issue = 12 | pages = 724–734 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26617334 | doi = 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.09.011 | s2cid = 259584956 | url = https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20151207-104216157 }}</ref> This was taken a step further in 2012, when a whole book was encoded onto DNA.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Church GM, Gao Y, Kosuri S | title = Next-generation digital information storage in DNA | journal = Science | volume = 337 | issue = 6102 | pages = 1628 | date = September 2012 | pmid = 22903519 | doi = 10.1126/science.1226355 | bibcode = 2012Sci...337.1628C | doi-access = free }}</ref> Paintings have also been produced using bacteria transformed with fluorescent proteins.<ref name=":6" /> | ||

| == |

== Viruses == | ||

| {{Main|Genetically modified virus}} | {{Main|Genetically modified virus}} | ||

| Viruses are often modified so they can be used as ] for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This process is called ] and if successful the recipient of the introduced DNA becomes a GMO. Different viruses have different efficiencies and capabilities. Researchers can use this to control for various factors; including the target location, insert size and duration of gene expression. Any dangerous sequences inherent in the virus must be removed, while those that allow the gene to be delivered effectively are retained.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Baldo A, van den Akker E, Bergmans HE, Lim F, Pauwels K | title = General considerations on the biosafety of virus-derived vectors used in gene therapy and vaccination | journal = Current Gene Therapy | volume = 13 | issue = 6 | pages = 385–94 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 24195604 | pmc = 3905712 | doi = 10.2174/15665232113136660005 }}</ref> | Viruses are often modified so they can be used as ] for inserting genetic information into other organisms. This process is called ] and if successful the recipient of the introduced DNA becomes a GMO. Different viruses have different efficiencies and capabilities. Researchers can use this to control for various factors; including the target location, insert size, and duration of gene expression. Any dangerous sequences inherent in the virus must be removed, while those that allow the gene to be delivered effectively are retained.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Baldo A, van den Akker E, Bergmans HE, Lim F, Pauwels K | title = General considerations on the biosafety of virus-derived vectors used in gene therapy and vaccination | journal = Current Gene Therapy | volume = 13 | issue = 6 | pages = 385–94 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 24195604 | pmc = 3905712 | doi = 10.2174/15665232113136660005 }}</ref> | ||

| While viral vectors can be used to insert DNA into almost any organism it is especially relevant for its potential in treating human disease. Although primarily still at trial stages,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/therapy/availability|title=Is gene therapy available to treat my disorder? |work = Genetics Home Reference |access-date= |

While viral vectors can be used to insert DNA into almost any organism it is especially relevant for its potential in treating human disease. Although primarily still at trial stages,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/therapy/availability|title=Is gene therapy available to treat my disorder? |work = Genetics Home Reference |access-date=14 December 2018}}</ref> there has been some successes using ] to replace defective genes. This is most evident in curing patients with ] rising from ] (ADA-SCID),<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | vauthors = Aiuti A, Roncarolo MG, Naldini L | title = ex vivo gene therapy in Europe: paving the road for the next generation of advanced therapy medicinal products | journal = EMBO Molecular Medicine | volume = 9 | issue = 6 | pages = 737–740 | date = June 2017 | pmid = 28396566 | pmc = 5452047 | doi = 10.15252/emmm.201707573 }}</ref> although the development of ] in some ADA-SCID patients<ref name="Lundstrom_2018">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lundstrom K | title = Viral Vectors in Gene Therapy | journal = Diseases | volume = 6 | issue = 2 | date = May 2018 | pmid = 29883422 | pmc = 6023384 | doi = 10.3390/diseases6020042 | page=42 | doi-access = free }}</ref> along with the death of ] in a 1999 trial set back the development of this approach for many years.<ref name="Sheridan_2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sheridan C | title = Gene therapy finds its niche | journal = Nature Biotechnology | volume = 29 | issue = 2 | pages = 121–8 | date = February 2011 | pmid = 21301435 | doi = 10.1038/nbt.1769 | s2cid = 5063701 }}</ref> In 2009, another breakthrough was achieved when an eight-year-old boy with ] regained normal eyesight<ref name="Sheridan_2011" /> and in 2016 ] gained approval to commercialize a gene therapy treatment for ADA-SCID.<ref name="ReferenceA" /> As of 2018, there are a substantial number of ]s underway, including treatments for ], ], ], ] and various ]s.<ref name="Lundstrom_2018" /> | ||

| The most common virus used for gene delivery |

The most common virus used for gene delivery comes from ] as they can carry up to 7.5 kb of foreign DNA and infect a relatively broad range of host cells, although they have been known to elicit immune responses in the host and only provide short term expression. Other common vectors are ]es, which have lower toxicity and longer-term expression, but can only carry about 4kb of DNA.<ref name="Lundstrom_2018" /> ]es make promising vectors, having a carrying capacity of over 30kb and providing long term expression, although they are less efficient at gene delivery than other vectors.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7024/ |title=HSV as a Vector in Vaccine Development and Gene Therapy | vauthors = Manservigi R, Epstein AL, Argnani R, Marconi P |date=2013 |publisher=Landes Bioscience }}</ref> The best vectors for long term integration of the gene into the host genome are ]es, but their propensity for random integration is problematic. ]es are a part of the same family as retroviruses with the advantage of infecting both dividing and non-dividing cells, whereas retroviruses only target dividing cells. Other viruses that have been used as vectors include ]es, ]es, ]es, ]es, ], ], and ]es.<ref name="Lundstrom_2018" /> | ||

| Most ] consist of viruses that have been ], disabled, weakened or killed in some way so that their ] properties are no longer effective. Genetic engineering could theoretically be used to create viruses with the virulent genes removed. This does not affect the viruses ], invokes a natural immune response and there is no chance that they will regain their virulence function, which can occur with some other vaccines. As such they are generally considered safer and more efficient than conventional vaccines, although concerns remain over non-target infection, potential side effects and ] to other viruses.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chan VS | title = Use of genetically modified viruses and genetically engineered virus-vector vaccines: environmental effects | journal = Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part A | volume = 69 | issue = 21 | pages = 1971–7 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 16982535 | doi = 10.1080/15287390600751405 }}</ref> Another approach is to use vectors to create novel vaccines for diseases that have no vaccines available or the vaccines that |