| Revision as of 23:17, 27 December 2004 edit142.166.200.154 (talk) →Early Biblical criticism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:41, 25 November 2024 edit undoFeline Hymnic (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers16,191 edits →Critical reassessment: add 'clarify' template | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Hypothesis to explain the origins and composition of the Torah}} | |||

| The '''documentary hypothesis''' is a ] held by many ]s and academics in the field of ] that the five books of ] (the ]) are a combination of documents from different sources. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} | |||

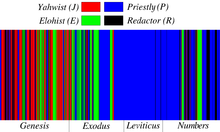

| [[File:Modern document hypothesis.svg|thumb|Diagram of the 20th century documentary hypothesis: | |||

| {{unbulleted list|J: ] (10th–9th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}}|E: ] (9th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}}|Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) ] historian|Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) ] historian|P*: ] (6th–5th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=41}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}}|D†: ]|R: redactor|DH: ] (books of ], ], ], ])}}]] | |||

| The '''documentary hypothesis''' ('''DH''') is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and ] (or ], the first five books of the Bible: ], ], ], ], and ]).{{sfn|Patzia|Petrotta|2010|p=37}} A version of the documentary hypothesis, frequently identified with the German scholar ], was almost universally accepted for most of the 20th century.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the ], ], ], and ] sources, frequently referred to by their initials.<ref group="Note">hence the alternative name ''JEDP'' for the documentary hypothesis</ref> The first of these, J, was dated to the ] (c. 950 BCE).{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}} E was dated somewhat later, in the 9th century BCE, and D was dated just before the reign of ], in the 7th or 8th century BCE. Finally, P was generally dated to the time of ] in the 5th century BCE.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=41}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}} The sources would have been joined at various points in time by a series of editors or "redactors".{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=viii}} | |||

| In general, the authorship of all the books of the ] is still an open topic of research. Historians are interested in learning about who wrote the books of the Bible and when they were written. Modern studies on this subject began in the ], and they constitute a lively field of activity even now. An authoritative and readable overview is provided by John Rogerson in ''Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany'' (1985). Assigning solid dates to any books of the Bible is difficult. This subject is covered in the article on ]. | |||

| The consensus around the classical documentary hypothesis has now collapsed.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of ], ], and ] in the mid-1970s,{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} who argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the ] (597–539 BCE),{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|pp=41–43}} and rejected the existence of a substantial E source.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=436}} They also called into question the nature and extent of the three other sources. Van Seters, Schmid, and Rendtorff shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in complete agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} As a result, there has been a revival of interest in "fragmentary" and "]" models, frequently in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=12}} Modern scholars also have given up the classical Wellhausian dating of the sources, and generally see the completed Torah as a product of the time of the Persian ] (probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its production as late as the ] (333–164 BCE), after the conquests of ].{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207, 224 fn.49}} | |||

| == Early Biblical criticism == | |||

| == History of the documentary hypothesis == | |||

| The famous ] scholar and physician ] first introduced the terms '']'' and '']'' or Elohistic and Jehovistic, in a little book titled ''Conjectures... sur Genèse'' ("Conjectures on the original documents that Moses appears to have used in composing the Book of Genesis"), anonymously printed in ], noting that the first chapter of ] uses only the word "Elohim" for ], while in other sections the word "Jehovah" is used. In the second and third chapters, the title and name are combined, giving rise to a new conception of the Deity as ''Jehovah Elohim'' ("Lord—God" as commonly translated in many English Bibles today). He speculated that Moses may have compiled the Genesis account from earlier documents, some perhaps dating back to Abraham, and that these had been combined into a single account. So, he began to explore the possibility of detecting and ] and assigning them to their original sources. He did this, taking as axiomatic that scriptural documents could be analyzed in the same manner as secular ones and the assumption that the varying use of terms indicated different writers. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] (or Pentateuch) is collectively the first five books of the Bible: ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|McDermott|2002|p=1}} According to tradition, they were dictated by God to Moses,{{sfn|Kugel|2008|p=6}} but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible, it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author.{{sfn|Campbell|O'Brien|1993|p=1}} As a result, the ] of the Torah had been largely rejected by leading scholars by the 17th century, with many modern scholars viewing it as a product of a long evolutionary process.{{sfn|Berlin|1994|p=113}}{{sfn|Baden|2012|p=13}}<ref group="Note" name="Moses">The reasons behind the rejection are covered in more detail in the article on ].</ref> | |||

| In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah.{{sfn|Berlin|1994|p=113}} In 1780, ], building on the work of the French doctor and ] ]'s "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the ] ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the ] ("E").{{sfn|Ruddick|1990|p=246}} These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when ] identified the ] as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D").{{sfn|Patrick|2013|p=31}} Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and ] ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}} | |||

| Using "Elohim" and "Yahweh" as a criterion, Astruc used columns titled respectively "A" and "B", and also set other pieces apart. The A and B narratives he regarded as originally complete and independent narratives. From this was born the practice of Biblical textual criticism that came to be known as ]. | |||

| ] brought Astruc's book to Germany and further differentiated the two chief documents through their linguistic peculiarities in ]. However, neither he nor Astruc denied Mosaic authorship, nor analyzed beyond the book of Exodus. | |||

| H. Ewald recognized that the documents that later came to be known as "P" and "J" could be seen in other books. F. Tuch showed that they were also recognizable in ]. | |||

| These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the ].{{sfn|Viviano|1999|pp=38–39}} The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=38}} The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=38}} The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by ] in 1853, who argued that the Pentateuch was made up of four documentary sources, the Priestly, Yahwist, and Elohist intertwined in Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers, and the stand-alone source of Deuteronomy.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=18–19}} At around the same period, ] argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while ] linked the four to an evolutionary framework: the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.{{sfn|Friedman|1997|p=24–25}} | |||

| ] (] - ]) joined this theory to one asserted by ] commentators by stating that the Book of ] was not written by the author(s) of the first four books of the Pentateuch. In ] he attributed Deuteronomy to the time of ] (ca ]). Soon other writers also began considering the idea. By ] Eichhorn abandoned claiming Mosaic Authorship of the Pentateuch. | |||

| === Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis === | |||

| About ], F. Bleek commented about the original relationship of Joshua to the Pentateuch in its continuation of the narrative in Deuteronomy, of which it formed the conclusion. The letters "J" for ''Jahwist'' and "E" ''Elohist'' were then designated for the documents. | |||

| ] | |||

| H. Hupfeld followed K. D. Ilgen in identifying two separate documents that used "Elohim". In ], Hupfeld set forth ] chapters 1-19 and 20 - 50 as being the two separate Elohistic source documents . He also emphasized the importance of the redactor of these documents. The arrangement of the documents that he followed was: First Elohist, Second Elohist, Jehovist, Deuteronomist: J, E, and D. | |||

| In 1878, ] published ''Geschichte Israels, Bd 1'' ('History of Israel, Vol 1').{{sfn|Wellhausen|1878}} The second edition was printed as '']'' ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel") in 1883,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1883}} and the work is better known under that name.{{sfn|Kugel|2008|p=41}} (The second volume, a synthetic history titled ''Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte'' ,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1894}} did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ('The Composition of the Hexateuch') of 1876–77, and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of ]'s ''Einleitung in das Alte Testament'' ('Introduction to the Old Testament'). | |||

| K. H. Graf showed that ] chapters 17 to 26 were to be discriminated by many individualities from the priestly document, and suggested a fifth document (to which the name "Holiness Code" was attached by A. Klostermann because this body of laws was marked by the declaration of God's holiness, and Israel's duty to be holy as his people. | |||

| Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, ], Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=20}} He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}} J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of ]; E was from the 9th century BCE in the northern ], and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of ]; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century BCE; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40–41}}{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=260}} | |||

| === Julius Wellhausen === | |||

| Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=260}} The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous, and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy, he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated, post-exilic period.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=51}} His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}}<ref group="Note" name="newer">The two-source hypothesis of Eichhorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".</ref> | |||

| In ] the ] historian ] published ''Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels'' (''Prolegomena to the History of Israel''). In this book he stated: "according to the historical and prophetical books of the Old Testament the priestly legislation of the middle books of the Pentateuch was unknown in pre-exilic time, and that this legislation must therefore be a late development."(2) The letter "P", for ''priestly'', became associated with this view. | |||

| == Critical reassessment == | |||

| Wellhausen argued that the Bible is an important source for historians, but cannot be taken literally. He argued that the "hexateuch," (including the ] or ], and the book of ]) was written by a number of people over a long period. Specifically, he narrowed the field to four distinct narratives, which he identified by the aforementioned ], ], ] and ] accounts. He also recognized a '''R'''edactor, who edited the four accounts into one text. (Some argue the redactor was ''Ezra'' the scribe). Using earlier propositions he argued that each of these sources has its own vocabulary, its own approach and concerns, and that the passages originally belonging to each account can be distinguished by differences in style (especially the name used for God, the grammar and word usage, the political assumptions implicit in the text, and the interests of the author). | |||

| ] | |||

| In the mid to late 20th century, new criticism of the documentary hypothesis formed.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to reevaluate the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: '']'' by ], ''Der sogenannte Jahwist'' ("The So-Called Yahwist") by ], and ''Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch'' ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by ]. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} | |||

| Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the ] (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the ] (597–539 BCE), or the late monarchic{{clarify|date=November 2024|reason=unclear to lay reader: needs a wikilink}} period at the earliest.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|pp=41–43}} Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=42}} | |||

| * '''The "J" source:''' In this source God's name is always presented as YHVH, which scholars transliterated in modern times as ''Jahweh'' (the previous ] was ''Jehovah''). | |||

| * '''The "E" source:''' In this source God's name is always presented as ''Elohim'' (Hebrew for God, or Power) until the revelation of God's name to Moses, after which God is referred to as YHVH. | |||

| * '''The "D" or "Dtr" source:''' The source that wrote the book of Deuteronomy, and the books of Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel and I and II Kings. | |||

| * '''The "P" source:''' The priestly material. Uses Elohim and El Shaddai as names of God. | |||

| Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=49}}{{sfn|Thompson|2000|p=8}}{{sfn|Ska|2014|pp=133–135}} By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a ], which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=77}} | |||

| Wellhausen argued that from the style and point of view of each source, one could draw inferences about the times in which the source was written (in other words, the historical value of the Bible is not that it reveals things about the events it describes, but rather that it reveals things about the people who wrote it). He argued that the progression evident in these four sources, from a relatively informal and decentralized relationship between people and God in the J account, to the relatively formal and centralized practices of the P account, one could see the development of institutionalized Israelite religion. | |||

| Some scholars use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=12}} The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of ] as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.{{sfn|Otto|2014|p=605}} Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=457}} The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.{{sfn|Otto|2014|p=609}} | |||

| A number of Wellhausen's specific interpretations, including his reconstruction of the order of the accounts as J-E-D-P has been questioned, and to a large degree rejected. Biblical scholars today suggest that he organized the narrative to culminate with P because he believed that the ] followed logically in this progression. In the ] the Israeli historian, Yehezkel Kaufmann, published ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile,'' in which he argued that the order of the sources would be J, E, P, and D. | |||

| The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the ] (539–333 BCE).{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207}}{{sfn|Whisenant|2010|p=679|ps=, "Instead of a compilation of discrete sources collected and combined by a final redactor, the Pentateuch is seen as a sophisticated scribal composition in which diverse earlier traditions have been shaped into a coherent narrative presenting a creation-to-wilderness story of origins for the entity 'Israel.'"}} A minority of scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the ] (333–164 BCE).{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207, 224 n. 49}} | |||

| == The modern documentary hypothesis == | |||

| A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=271}} This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=271}} Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=272}} | |||

| The documentary understanding of the origin of the five books of Moses was immediately seized upon by other scholars, and within a few years became the predominant theory. While many of Wellhausen's specific claims have since been dismissed, the general idea that the five books of Moses had a composite origin is now fully accepted by ]. | |||

| == The Torah and the history of Israel's religion == | |||

| Note that the documentary hypothesis is not one specific theory. Rather, this name is given to any understanding of the origin of the Torah that recognizes that there are basically four sources that were somehow redacted together into a final version. One could claim that one redactor wove together four specific texts, or one could hold that entire nation of ] slowly created a consensus work based on various strands of the Israelite tradition, or anything in between. Gerald A. Larue writes "Back of each of the four sources lie traditions that may have been both oral and written. Some may have been preserved in the songs, ballads, and folktales of different tribal groups, some in written form in sanctuaries. The so-called 'documents' should not be considered as mutually exclusive writings, completely independent of one another, but rather as a continual stream of literature representing a pattern of progressive interpretation of traditions and history." (''Old Testament Life and Literature'' 1968) | |||

| {{See also|History of ancient Israel and Judah|Origins of Judaism}} | |||

| Wellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=182}} Modern scholars of Israel's religion have become much more circumspect in how they use the Old Testament, not least because many have concluded that the Hebrew Bible is not a reliable witness to the religion of ancient Israel and Judah,<ref name="Lupovitch">{{cite book |last1=Lupovitch |first1=Howard N. |date=2010 |title=Jews and Judaism in World History |chapter=The world of the Hebrew Bible |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s7uLAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |location=] |publisher=] |pages=5–10 |isbn=978-0-203-86197-4}}</ref> representing instead the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community centered in ] and devoted to the exclusive worship of the god ].{{sfn|Stackert|2014|p=24}}{{sfn|Wright|2002|p=52}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| ] Jews and Christians reject the documentary theory entirely, and accept the traditional view that the whole Torah is the work of ]. For most Orthodox Jews and most traditional Christians, the divine origins of the five books of Moses in its entirety is accepted as a given. Some Christians, such as the translators of the ] of the Bible believe that Moses was the author of much of the text, and was the editor and compiler of the rest of the text. Over the last century an entire literature has developed within these religious communities, dedicated to the refutation of ] in general, and the documentary hypothesis in particular. They have had a tendency to focus on the extra-literary analysis of Pentateuchal scholars such as the oral traditionalists. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], Jewish scholar who was critical of the documentary hypothesis | |||

| * ], a similar theory for the construction of the ] | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| === Richard Elliot Friedman === | |||

| {{Reflist |group="Note"}} | |||

| In recent years attempts have been made to separate the J, E, D, and P portions. ]'s ''Who Wrote The Bible?'' is a very reader-friendly and yet comprehensive argument explaining Friedman's opinions as to the possible identity of each of those authors, and, more important, why they wrote what they wrote. Harold Bloom then wrote ''"The Book of J",'' in which he claims to have reconstructed the book that J wrote (though, certainly, much of J's original contribution must have been lost in the consolidation, if one believes the four-author theory). Bloom (picking up on Friedman's earlier speculation) also indicates that he believes that J was a woman, but this is not accepted by other scholars. | |||

| More recently, Friedman came out with ''The Hidden Book in the Bible'', in which he makes a comprehensive argument for his theory that J wrote not only the portions of the Torah commonly attributed to J, but also sections of Judges, Joshua and 1&2 Samuel (which Bloom and earlier Biblical scholars attributed to another source, the ]), which contained the bulk of the accounts of the life of King ], with a close thematic interrelationship between the earlier and later portions of what Friedman argues is a single united work by one author of ]an literary ability. | |||

| Some scholars assert that the Documentary Hypothesis does make testable predictions that have been verified, such as Professor Jeffrey H. Tigay. | |||

| One interesting comment about the redaction of the Hebrew Bible can be found in Blenkinsopp (pages 239-243), who notes the following: | |||

| :<i>After the capture of Babylon by Cyrus II in 539 B.C., Jews living in the province of Judah and the Babylonian diaspora came under Iranian rule which lasted for about two centuries, until the conquest of Alexander. During the two centuries the policy of the Achemenids was to respect the very diverse political and social systems obtaining throughout their vast empire, so long as edicts were obeyed and tribute paid....One aspect of this imperial policy was the insistence on local self-definition inscribed primarily in a codified and standardized corpus of traditional law backed by the central government and its regional representatives. The Persians, it seems, had no unified legal code of their own.</i> | |||

| Blenkinsopp then goes on to suggest that redaction may have served a political purpose for the Persians, to provide for the regional law that Judah would have needed. | |||

| === Hans Heinrich Schmid === | |||

| Critical analysis that rejects the partitioning scheme of Wellhausen includes Hans Heinrich Schmid, whose ] work, ''Der sogenannte Jahwist'' or translated, ''The So-called Yahwist'', almost completely eliminates the J document and, according to Blenkinsopp, if taken to its logical extreme, eliminates all narrative sources other than the Deuteronomic author. | |||

| === The oral traditionalists === | |||

| There is also the viewpoint of the oral traditionalists. The first of these was Hermann Gunkel, who viewed the Torah originally as a kind of saga, much like the Iliad or Odyssey, passed down by word of mouth by an illiterate people. More recently, this point of view has been represented by Scandanavian scholar Ivan Engnell, who believes the whole of the Torah was transmitted orally to the post-exilic period, at which point it was written down in a single document by the author normally recognized as P. | |||

| The view of ] professor Rolf Rendtorff is that larger chunks of narrative within J and E evolved independently of one another (hence no J and E authors) and that these narrative episodes were combined editorially at a later stage, by a Deuteronomic redactor. In this synthesis, he allows for a post-exilic P source, but far reduced from the notions of Wellhausen. | |||

| === Internal textual evidence === | |||

| The main areas considered by these critics when supporting the Documentary Hypothesis are: | |||

| #The Variations in the Divine Names in Genesis; | |||

| #The Secondary Variations in Diction and Style; | |||

| #The parallel or Duplicate Accounts (Doublets); | |||

| #The Continuity of the Various Sources. | |||

| #The political assumptions implicit in the text; | |||

| #The interests of the author. | |||

| Doublets and triplets are stories that are repeated with different points of view. Famous doublets include ]'s creation accounts; the stories of the covenant between God and Abraham; the naming of Isaac; the two stories in which ] claims to a king that his wife is really his sister; the two stories of the revelation to Jacob at ]. A famed triplet is the three different versions of how the town of ] got its name. | |||

| There are many portions of the Torah which seem to imply more than one author. Some examples include: | |||

| * Genesis 11:31 describes Abraham as living in the ] of the ]. But the Chaldeans did not exist at the time of Abraham. | |||

| * Numbers 25 describes the rebellion at Peor, and refers to ] women; the next sentence says the women were ]ites. | |||

| * Deuteronomy 34 describes the death of Moses. | |||

| * The list of ]ite kings included Kings who were not born until after Moses' death. | |||

| * Some locations are identified by names which did not exist until long after the time of Moses. | |||

| * The Torah often says that something has lasted "to this day," which seems to imply that the words were written at a later date. Classical commentaries usually interpret such verses to mean until the day they are read, in other words forever. | |||

| * Deuteronomy 34:10 states "There never again arose a prophet in Israel like Moses..." which seems to imply that the verse was written long after. However, this can be understood as "There would never again arise.." | |||

| All the points raised are contentious however and those who follow traditional views of the Bible's origin do consider them to hold much weight. | |||

| == Traditional Jewish beliefs == | |||

| The traditional Jewish view is that ] revealed his will to ] at ] in a verbal fashion. This dictation is said to have been exactly transcribed by Moses. The Torah was then exactly copied by scribes, from one generation to the next. Based on the ] (Tractate Gittin 60a) some believe that the Torah may have been given piece-by-piece, over the 40 years that the Israelites wandered in the desert. In either case, the Torah is considered a direct quote from God. | |||

| However, classical Judaism notes a number of exceptions: Over the millennia scribal errors have crept into the text of the Torah. The ] (] to ] CE) compared all extant variations and attempted to create a definitive text. Rabbi ] and Joseph Bonfils observed that some phrases in the Torah present information that should only have been known after the time of Moses. Some classical ]s drew on their obervations to postulate that these sections of the Torah were written by ] or perhaps some later prophet. Other rabbis would not accept this view. | |||

| The ] (tractate Shabbat 115b) states that a peculiar section in the ] 10:35-36, surrounded by inverted ] letter <i>nuns</i>, in fact is a separate book. On this verse a ] on the book of Mishle states that "These two verses stem from an independent book which existed, but was suppressed!" Another, possibly earlier midrash, <i>Ta'ame Haserot Viyterot</i>, states that this section actually comes from the book of prophecy of Eldad and Medad. The Talmud says that four books of the Torah were dictated by God, but Deuteronomy was written by Moses in his own words (Talmud Bavli, Megillah 31b). For more information on these issues from an Orthodox Jewish perspective, see ''Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations,'' edited by Shalom Carmy (Jason Aronson, Inc.) and ''Handbook of Jewish Thought,'' Volume I, by ] (Moznaim Pub.) | |||

| Individual ]s and scholars have on occasion pointed out that the Torah showed signs of not being written entirely by Moses. | |||

| * Rabbi Judah ben Ilai held that the final verses of the Torah must have been written by Joshua. (Talmud, Bava Batra 15a and Menachot 30a, and in Midrash Sifrei 357.) | |||

| * Parts of the Midrash retain evidence of the ]al period during which Ezra redacted and canonized the text of the Torah as we know it today. A rabbinic tradition states that at this time (440 B.C.E.) the text of the Torah was edited by ], and there were ten places in the Torah where he was uncertain as to how to fix the text; these passages were marked with special punctuation marks called the ''eser nekudot''. | |||

| * In the middle ages, Rabbi ] and others noted that there were several places in the Torah that apparently could not have been written in Moses's lifetime. For example, see Ibn Ezra's comments on ] 12:6, 22;14, ] 1:2, 3:11 and 34:1,6. Ibn Ezra's comments were elucidated by Rabbi Joseph Bonfils in his commentary on Ibn Ezra's work. | |||

| * In the ], the commentator R. Joseph ben Isaac, known as the Bekhor Shor, noted that a number of wilderness narratives in Exodus and Numbers are very similar, in particular, the incidents of water from the rock, and the stories about manna and the quail. He theorized that both of these incidents actually happened once, but that parallel traditions about these events eventually developed, both of which made their way into the Torah. | |||

| * In the ], R. Hezekiah ben Manoah (known as the Hizkuni) noticed the same textual anomalies that Ibn Ezra noted; thus R. Hezekiah's commentary on Genesis 12:6 notes that this section "is written from the perspective of the future.". | |||

| * In the ], Rabbi Yosef Bonfils while discussing the comments of Ibn Ezra, noted: "Thus it would seem that Moses did not write this word here, but Joshua or some other prophet wrote it. Since we believe in the prophetic tradition, what possible difference can it make whether Moses wrote this or some other prophet did, since the words of all of them are true and prophetic?" | |||

| * ] jokingly expands the ] '''R''' for the redactor to ''Rabbenu'' — Our Master | |||

| Recent defenders of the classical Jewish view include Rabbi ] (known for his responsa titled "Melamed le-Ho'il") of Berlin. | |||

| == Traditional Christian beliefs == | |||

| The traditional view among Christians was that Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible, apart from a number of passages, such as the death of Moses, written by his successor Joshua. However, a number of ] Christian writers expressed doubts about this traditional view. For example, in the ], Carlstadt noticed that the style of the account of the death of Moses was the same as that of the preceding portions of Deuteronomy, suggesting that whoever wrote about the death of Moses also wrote larger portions of the Torah. | |||

| By the ], some commentators argued outright that Moses did not write most of the Pentateuch. For instance, in ], ] in ''Leviathan'', ch. 33, argued that the Pentateuch was written after Moses's day on account of Deut. 34:6 ("no man knoweth of his sepulchre to this day"), Gen. 12:6 ("and the ]ite was then in the land"), and Num. 21:14 (referring to a previous book of Moses's deeds). Others include Isaac de la Peyrère, ], ], and ]. Nevertheless, these people found their works condemned and even banned, and de la Peyrère and Hampden were forced to recant. | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| == Bibliography == | |||

| *Allis, Oswald T. ''The Five Books of Moses'', Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., Phillipsburg, New Jersey, USA, 1949, pages 17 and 22. | |||

| {{Refbegin|}} | |||

| *Blenkinsopp, Joseph ''The Pentateuch'', Doubleday, NY, USA 1992. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Baden|first=Joel S.|title=The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis|publisher=Yale University Press|year=2012|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Beg7LeeNGlkC|isbn=978-0-300-15263-0|series=Anchor Yale Reference Library}} | |||

| *Bloom, Harold and Rosenberg, David ''The Book of J'', Random House, NY, USA 1990. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Barton|first=John|chapter=Biblical Scholarship on the European Continent, in the UK, and Ireland|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMzUBQAAQBAJ&q=%22sure+of+only+two+things+about+the+sources+of+the+Pentateuch%22&pg=PA311|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| *] "Gods and Heroes of the Levant:1500-500 B.C." ''The Masks of God 3: Occidental Mythology'', Penguin Books, NY, USA, 1964. | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Barton|first1=John|last2=Muddiman|first2=John|title=The Pentateuch|year=2010|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ldMUDAAAQBAJ&q=%221860s%22%22leading+scholars%22%22supplementary+hypothesis%22&pg=PA18|isbn=978-0-19-958024-8}} | |||

| *Dever, William G. ''What Did The Biblical Writers Know & When Did They Know It?'' William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2001. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Berlin|first=Adele|title=Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative|publisher=Eisenbrauns|year=1994|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eLoBhPENIBQC&q=%22source+criticism%22%22detecting+in+the+text+evidence+of+its+earlier+stages%22&pg=PA113|isbn=978-1-57506-002-6}} | |||

| *Finkelstein, I. and Silberman, N. A. ''The Bible Unearthed'', Simon and Schuster, NY, USA, 2001. | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism |last=Berman |first=Joshua A. |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-19-065880-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rWBwvgAACAAJ}} | |||

| *Fox, Robin Lane, "The Unauthorized Version." A classics scholar offers a measured view for the layman. | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Brettler|first=Marc Zvi|editor1-last=Berlin|editor1-first=Adele|editor2-last=Brettler|editor2-first=Marc Zvi|title=The Jewish Study Bible|chapter=Torah: Introduction|date=2004|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780195297515|url-access=registration|isbn=978-0-19-529751-5}} | |||

| *Friedman, Richard E. ''Who Wrote The Bible?'', Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987. | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Campbell|first1=Antony F.|last2=O'Brien|first2=Mark A.|title=Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations|publisher=Fortress Press|year=1993|url=https://archive.org/details/sourcesofpentate0000camp|url-access=registration|isbn=978-1-4514-1367-0}} | |||

| *Friedman, Richard E. ''The Hidden Book in the Bible'', HarperSan Francisco, NY, USA, 1998. | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Carr|first1=David M.|chapter=Genesis|editor1-last=Coogan|editor1-first=Michael David|editor2-last=Brettler|editor2-first=Marc Zvi|editor3-last=Newsom|editor3-first=Carol Ann|title=The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2007|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22collapse+of+consensus%22%22debate+surrounding+virtually+every+aspect%22&pg=PA434|isbn=978-0-19-528880-3}} | |||

| *Kaufmann, Yehezkel, Greenberg, Moishe (translator) ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile'', University of Chicago Press, 1960. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Carr|first=David M.|chapter=Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=could+be+presupposed+as+a+givenfor+over+a+hundred+years&pg=PA434|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| *Larue, Gerald A. ''Old Testament Life and Literature'', Allyn & Bacon, Inc, Boston, MA, USA 1968 | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch|last=Frei|first=Peter|publisher=SBL Press|year=2001|isbn=9781589830158|location=Atlanta, GA|pages=6|editor-last=Watts|editor-first=James|chapter=Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary}} | |||

| *McDowell, Josh ''More Evidence That Demands a Verdict: Historical Evidences for the Christian Scriptures'', Here's Life Publishers, Inc. 1981, p. 45. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Friedman|first=Richard Elliott|title=Who Wrote the Bible?|publisher=HarperOne|year=1997}} | |||

| *Mendenhall, George E. ''The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition'', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Gaines|first=Jason M.H.|title=The Poetic Priestly Source|publisher=Fortress Press|year=2015|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pnHhCwAAQBAJ&q=%22documentary+hypothesis%22%22still+has+adherents%22&pg=PA271|isbn=978-1-5064-0046-4}} | |||

| *Mendenhall, George E. ''Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context'', Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last1=Gertz|first1=Jan C.|last2=Levinson|first2=Bernard M.|last3=Rom-Shiloni|first3=Dalit|chapter=Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory|editor1-last=Gertz|editor1-first=Jan C.|editor2-last=Levinson|editor2-first=Bernard M.|editor3-last=Rom-Shiloni|editor3-first=Dalit|title=The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2017|volume=44 |issue=4 |page=481 |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/30485934}} | |||

| *Nicholson, E. ''The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen'', Oxford University Press, 2003. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Gmirkin|first=Russell|title=Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus|publisher=Bloomsbury|year=2006|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CKuoAwAAQBAJ&q=%22no+reference+to+a+written+torah%22&pg=PA32|isbn=978-0-567-13439-4}} | |||

| *Rogerson, J. ''Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany'', SPCK/Fortress, 1985. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Greifenhagen|first=Franz V.|title=Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map|publisher=Bloomsbury|year=2003|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r1evAwAAQBAJ&q=%22final+form+sometime+in+the+Persian+period%22&pg=PA207|isbn=978-0-567-39136-0}} | |||

| *Spinoza, Benedict de ''A Theologico-Political Treatise'' Dover, NY, USA, 1951, Chapter 8. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Houston|first=Walter|title=The Pentateuch|publisher=SCM Press|year=2013|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IbALAQAAQBAJ&q=%22two+other+possibilities%22%22are+now+being+revived%22&pg=PA93|isbn=978-0-334-04385-0}} | |||

| *Tigay, Jeffrey H. "An Empirical Basis for the Documentary Hypothesis" ''Journal of Biblical Literature'' Vol.94, No.3 Sept. 1975, pages 329-342. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kawashima|first=Robert S.|chapter=Sources and Redaction|editor1-last=Hendel|editor1-first=Ronald|title=Reading Genesis|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2010|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H4JvhWo04oEC&q=%22biblicists+generally+refer+to+these+sources+as%22&pg=PA52|isbn=978-1-139-49278-2}} | |||

| *Tigay, Jeffrey, Ed. ''Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism'' University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1986 | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Kratz|first=Reinhard G.|chapter=Rewriting Torah|editor1-last=Schipper|editor1-first=Bernd|editor2-last=Teeter|editor2-first=D. Andrew|title=Wisdom and Torah: The Reception of 'Torah' in the Wisdom Literature of the Second Temple Period|year=2013|publisher=BRILL|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nbDKAQAAQBAJ&q=%22+in+particular+in+the+documentary+and+fragmentary+hypothesis%22&pg=PA282|isbn=9789004257368}} | |||

| *Wiseman, P. J. ''Ancient Records and the Structure of Genesis'' Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, TN, USA 1985 | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Kratz|first=Reinhard G.|title=The Composition of the Narrative Books of the Old Testament|year=2005|publisher=A&C Black|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g0WnSW4Pc8oC|isbn=9780567089205}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kugel|first=James L.|author-link=James L. Kugel|title=How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now|publisher=FreePress|year=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=msdh9mmGHN4C|isbn=978-0-7432-3587-7}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kurtz|first=Paul Michael|title=Kaiser, Christ, and Canaan: The Religion of Israel in Protestant Germany, 1871–1918|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2018|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LmuKDwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-3-16-155496-4}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Levin|first=Christoph|title=Re-Reading the Scriptures|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2013|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aSNZ76USaYgC&q=Levin+Re-Reading+the+SCriptures|isbn=978-3-16-152207-9}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=McDermott|first=John J.|title=Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction|publisher=Pauline Press|year=2002|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dkr7rVd3hAQC&q=not+the+work+of+a+single+authorcomposed+over+several+centuries&pg=PA21|isbn=978-0-8091-4082-4}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=McEntire|first=Mark|title=Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch|publisher=Mercer University Press|year=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VwOs9f1FpmsC&q=%22Josianic+Reform+of+the+late+seventh+century+BCE%22&pg=PA7|isbn=978-0-88146-101-5}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|last=McKim|first=Donald K.|title=Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms|year=1996|publisher=Westminster John Knox|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UJ9PYdzKf90C&q=dictionary+documentary+hypothesis&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-664-25511-4}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Miller|first1=Patrick D.|title=Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays|year=2000|publisher=A&C Black|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wKRiloF-00oC|isbn=978-1-84127-142-2}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Monroe|first=Lauren A.S.|title=Josiah's Reform and the Dynamics of Defilement|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2011|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bqpoAgAAQBAJ&q=%22date+of+Deuteronomy+into+the+exilic%22&pg=PA135|isbn=978-0-19-977536-1}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Moore|first1=Megan Bishop|last2=Kelle|first2=Brad E.|title=Biblical History and Israel's Past|year=2011|publisher=Eerdmans|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qjkz_8EMoaUC&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-8028-6260-0}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Nicholson|first=Ernest Wilson|title=The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=opBBTHT13yoC|isbn=978-0-19-925783-6}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Otto|first=Eckart|chapter=The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22This+change+of+research+paradigms%22&pg=PA609|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Patrick|first=Dale|title=Deuteronomy|year=2013|publisher=Chalice Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NkP4QlnlEmYC&q=%22De+Wette%27s+identification%22%22large+majority+of+critical+biblical+scholars%22&pg=PA69|isbn=978-0-8272-0566-6}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Patzia|first1=Arthur G.|last2=Petrotta|first2=Anthony J.|title=Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies|year=2010|publisher=InterVarsity Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=btEJAwAAQBAJ&q=dictionary+documentary+hypothesis&pg=PA37|isbn=978-0-8308-6702-8}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Empirical Models Challenging Biblical Criticism |last=Person |first=Raymond F. |publisher=SBL Press |year=2016 |isbn=978-0-88414-149-5 |editor-last=Person |editor-first=Raymond F. |chapter=The Problem of “Literary Unity” from the Perspective of the Study of Oral Traditions |editor-last2=Rezetko |editor-first2=Robert |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ViYiDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA217}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=How the Bible is Written |last=Rendsburg |first=Gary |publisher=Hendrickson Publishers |year=2019 |isbn=978-1-68307-197-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O7nFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA468}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Ruddick|first=Eddie L.|chapter=Elohist|editor1-last=Mills|editor1-first=Watson E.|editor2-last=Bullard|editor2-first=Roger Aubrey|title=Mercer Dictionary of the Bible|publisher=Mercer University Press|year=1990|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&q=%22These+studies+later+guided+Eichhorn%22&pg=PA246|isbn=978-0-86554-373-7}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Ska|first=Jean-Louis|title=Introduction to reading the Pentateuch|year=2006|isbn=9781575061221|publisher=Eisenbrauns|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7cdy67ZvzdkC&pg=PA217}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Ska|first=Jean Louis|chapter=Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22Persian+period+as+the+most+important%22&pg=PA430|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Stackert|first=Jeffrey|title=A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2014|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DsCiAwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-0-19-933645-6}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Thompson|first=Thomas L.|title=Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources|year=2000|publisher=BRILL|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RwrrUuHFb6UC&q=long+folk+history+long+antedating&pg=PA8|isbn=9004119434}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Van Seters|first=John|title=The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary|year=2015|publisher=Bloomsbury T&T Clark|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=42-_CQAAQBAJ&q=%22new+supplementary+model%3A+van+seters%22&pg=PA55|isbn=978-0-567-65880-7}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Viviano|first=Pauline A.|chapter=Source Criticism|editor1-last=Haynes|editor1-first=Stephen R.|editor2-last=McKenzie|editor2-first=Steven L.|title=To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Application|year=1999|publisher=Westminster John Knox|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kpDceeylCjYC&q=Viviano+%22source+criticism%22&pg=PA35|isbn=978-0-664-25784-2}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Geschichte Israels |date=1878 |volume=1 |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/geschichteisrae00wellgoog}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels |date=1883 |volume=1 |edition=2nd |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/prolegomenazurg01wellgoog}} ; | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte |date=1894 |volume=2 |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/israelitischeun00wellgoog}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Whisenant |first=Jessica |title=''The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance'' by Gary N. Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson |journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society |volume=130 |issue=4 |year=2010 |pages=679–681 |jstor=23044597 }} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Wright|first1=J. Edward|title=The Early History of Heaven|year=2002|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lKvMeMorNBEC&q=Mesopotamian&pg=PA42|isbn=978-0-19-534849-1}} | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| == |

==External links== | ||

| {{Wikiversity|Bible, English, King James, According to the documentary hypothesis}} | |||

| * | |||

| *{{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| * | |||

| *] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:41, 25 November 2024

Hypothesis to explain the origins and composition of the Torah

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE)

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE)

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE)

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings)

The documentary hypothesis (DH) is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). A version of the documentary hypothesis, frequently identified with the German scholar Julius Wellhausen, was almost universally accepted for most of the 20th century. It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, and Priestly sources, frequently referred to by their initials. The first of these, J, was dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE). E was dated somewhat later, in the 9th century BCE, and D was dated just before the reign of King Josiah, in the 7th or 8th century BCE. Finally, P was generally dated to the time of Ezra in the 5th century BCE. The sources would have been joined at various points in time by a series of editors or "redactors".

The consensus around the classical documentary hypothesis has now collapsed. This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of John Van Seters, Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Rolf Rendtorff in the mid-1970s, who argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE), and rejected the existence of a substantial E source. They also called into question the nature and extent of the three other sources. Van Seters, Schmid, and Rendtorff shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in complete agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it. As a result, there has been a revival of interest in "fragmentary" and "supplementary" models, frequently in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. Modern scholars also have given up the classical Wellhausian dating of the sources, and generally see the completed Torah as a product of the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its production as late as the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE), after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

History of the documentary hypothesis

The Torah (or Pentateuch) is collectively the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. According to tradition, they were dictated by God to Moses, but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible, it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author. As a result, the Mosaic authorship of the Torah had been largely rejected by leading scholars by the 17th century, with many modern scholars viewing it as a product of a long evolutionary process.

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780, Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete Jean Astruc's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist ("E"). These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when Wilhelm de Wette identified the Deuteronomist as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D"). Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and Priestly ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.

These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the supplementary. The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology. The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources. The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by Hermann Hupfeld in 1853, who argued that the Pentateuch was made up of four documentary sources, the Priestly, Yahwist, and Elohist intertwined in Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers, and the stand-alone source of Deuteronomy. At around the same period, Karl Heinrich Graf argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while Wilhelm Vatke linked the four to an evolutionary framework: the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.

Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis

In 1878, Julius Wellhausen published Geschichte Israels, Bd 1 ('History of Israel, Vol 1'). The second edition was printed as Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel") in 1883, and the work is better known under that name. (The second volume, a synthetic history titled Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte , did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ('The Composition of the Hexateuch') of 1876–77, and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of Friedrich Bleek's Einleitung in das Alte Testament ('Introduction to the Old Testament').

Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, Eduard Eugène Reuss, Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship. He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last. J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of Solomon; E was from the 9th century BCE in the northern Kingdom of Israel, and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of King Josiah; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century BCE; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.

Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel. The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous, and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy, he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated, post-exilic period. His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.

Critical reassessment

In the mid to late 20th century, new criticism of the documentary hypothesis formed. Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to reevaluate the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: Abraham in History and Tradition by John Van Seters, Der sogenannte Jahwist ("The So-Called Yahwist") by Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by Rolf Rendtorff. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.

Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE), or the late monarchic period at the earliest. Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis.

Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases. By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.

Some scholars use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses. Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain. The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.

The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE). A minority of scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).

A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel. This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history. Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.

The Torah and the history of Israel's religion

See also: History of ancient Israel and Judah and Origins of JudaismWellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional. Modern scholars of Israel's religion have become much more circumspect in how they use the Old Testament, not least because many have concluded that the Hebrew Bible is not a reliable witness to the religion of ancient Israel and Judah, representing instead the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community centered in Jerusalem and devoted to the exclusive worship of the god Yahweh.

See also

- Authorship of the Bible

- Biblical criticism

- Books of the Bible

- Dating the Bible

- Mosaic authorship

- Umberto Cassuto, Jewish scholar who was critical of the documentary hypothesis

- Q Source, a similar theory for the construction of the Synoptic Gospels

Notes

- hence the alternative name JEDP for the documentary hypothesis

- The reasons behind the rejection are covered in more detail in the article on Mosaic authorship.

- The two-source hypothesis of Eichhorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".

References

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 41.

- Patzia & Petrotta 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Carr 2014, p. 434.

- Van Seters 2015, p. viii.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, p. 41.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, pp. 41–43.

- Carr 2014, p. 436.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, p. 12.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 fn.49.

- McDermott 2002, p. 1.

- Kugel 2008, p. 6.

- Campbell & O'Brien 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Berlin 1994, p. 113.

- Baden 2012, p. 13.

- Ruddick 1990, p. 246.

- Patrick 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 19.

- Viviano 1999, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 38.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 18–19.

- Friedman 1997, p. 24–25.

- Wellhausen 1878.

- Wellhausen 1883.

- Kugel 2008, p. 41.

- Wellhausen 1894.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 20.

- Viviano 1999, p. 40–41.

- ^ Gaines 2015, p. 260.

- Viviano 1999, p. 51.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 42.

- Viviano 1999, p. 49.

- Thompson 2000, p. 8.

- Ska 2014, pp. 133–135.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 77.

- Otto 2014, p. 605.

- Carr 2014, p. 457.

- Otto 2014, p. 609.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207.

- Whisenant 2010, p. 679, "Instead of a compilation of discrete sources collected and combined by a final redactor, the Pentateuch is seen as a sophisticated scribal composition in which diverse earlier traditions have been shaped into a coherent narrative presenting a creation-to-wilderness story of origins for the entity 'Israel.'"

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 n. 49.

- ^ Gaines 2015, p. 271.

- Gaines 2015, p. 272.

- Miller 2000, p. 182.

- Lupovitch, Howard N. (2010). "The world of the Hebrew Bible". Jews and Judaism in World History. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-203-86197-4.

- Stackert 2014, p. 24.

- Wright 2002, p. 52.

Bibliography

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis. Anchor Yale Reference Library. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15263-0.

- Barton, John (2014). "Biblical Scholarship on the European Continent, in the UK, and Ireland". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2010). The Pentateuch. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958024-8.

- Berlin, Adele (1994). Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-002-6.

- Berman, Joshua A. (2017). Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-065880-9.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2004). "Torah: Introduction". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-529751-5.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1367-0.

- Carr, David M. (2007). "Genesis". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-528880-3.

- Carr, David M. (2014). "Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Frei, Peter (2001). "Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary". In Watts, James (ed.). Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781589830158.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott (1997). Who Wrote the Bible?. HarperOne.

- Gaines, Jason M.H. (2015). The Poetic Priestly Source. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-0046-4.

- Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (2017). "Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory". In Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (eds.). The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Vol. 44. Mohr Siebeck. p. 481.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-39136-0.

- Houston, Walter (2013). The Pentateuch. SCM Press. ISBN 978-0-334-04385-0.

- Kawashima, Robert S. (2010). "Sources and Redaction". In Hendel, Ronald (ed.). Reading Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49278-2.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2013). "Rewriting Torah". In Schipper, Bernd; Teeter, D. Andrew (eds.). Wisdom and Torah: The Reception of 'Torah' in the Wisdom Literature of the Second Temple Period. BRILL. ISBN 9789004257368.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2005). The Composition of the Narrative Books of the Old Testament. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567089205.

- Kugel, James L. (2008). How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. FreePress. ISBN 978-0-7432-3587-7.

- Kurtz, Paul Michael (2018). Kaiser, Christ, and Canaan: The Religion of Israel in Protestant Germany, 1871–1918. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-155496-4.

- Levin, Christoph (2013). Re-Reading the Scriptures. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-152207-9.

- McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4082-4.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-88146-101-5.

- McKim, Donald K. (1996). Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25511-4.

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-142-2.

- Monroe, Lauren A.S. (2011). Josiah's Reform and the Dynamics of Defilement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977536-1.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- Nicholson, Ernest Wilson (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925783-6.

- Otto, Eckart (2014). "The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Patrick, Dale (2013). Deuteronomy. Chalice Press. ISBN 978-0-8272-0566-6.

- Patzia, Arthur G.; Petrotta, Anthony J. (2010). Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-6702-8.

- Person, Raymond F. (2016). "The Problem of "Literary Unity" from the Perspective of the Study of Oral Traditions". In Person, Raymond F.; Rezetko, Robert (eds.). Empirical Models Challenging Biblical Criticism. SBL Press. ISBN 978-0-88414-149-5.

- Rendsburg, Gary (2019). How the Bible is Written. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-68307-197-6.

- Ruddick, Eddie L. (1990). "Elohist". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Ska, Jean Louis (2014). "Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Stackert, Jeffrey (2014). A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933645-6.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2000). Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. BRILL. ISBN 9004119434.

- Van Seters, John (2015). The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary. Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-65880-7.

- Viviano, Pauline A. (1999). "Source Criticism". In Haynes, Stephen R.; McKenzie, Steven L. (eds.). To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Application. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25784-2.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1878). Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1883). Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer. Project Gutenberg edition; full text at sacred-texts.com

- Wellhausen, Julius (1894). Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte. Vol. 2. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Whisenant, Jessica (2010). "The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance by Gary N. Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (4): 679–681. JSTOR 23044597.

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534849-1.

External links

Media related to Documentary hypothesis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Documentary hypothesis at Wikimedia Commons- Wikiversity – The King James Version according to the documentary hypothesis