| Revision as of 22:18, 5 December 2006 editOpiner (talk | contribs)1,257 edits This section is the quote farm.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:20, 3 November 2024 edit undoArjayay (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers625,278 editsm Duplicate word reworded | ||

| (406 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Aspect of Muhammad's life}} | |||

| {{Muhammad}} | {{Muhammad}} | ||

| The '''diplomatic career of Muhammad''' ({{Circa|570}} – 8 June 632) encompasses Muhammad's leadership over the growing ] community ('']'') in early Arabia and his correspondences with the rulers of other nations in and around Arabia. This period was marked by the change from the customs of the period of '']'' in ] to an early Islamic system of governance, while also setting the defining principles of ] in accordance with ] and an ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ''']''' (c. ]–]) is documented as having engaged '''as a diplomat''' during his propagation of ] and leadership over the growing ] ]. He established a method of communication with other tribal or national leaders through ]s,<ref name="isal">Irfan Shahid, Arabic literature to the end of the Umayyad period, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol 106, No. 3, p.531 </ref> assigned ]s,<ref name="m412"/><!-- this cite is for p. 412 onwards which mentions a number of envoys --> or by visiting them personally, such as at ].<ref name="w81">Watt (1974) p. 81</ref> Instances of written correspondence include letters to ], the ] and the ]. Although it is likely that Muhammad had assumed contact with other leaders within the ], some have questioned whether letters had been sent beyond these boundaries.<ref name="f28">Forward (1998) pp. 28—29</ref> | |||

| The two primary Arab tribes of Medina, the ] and the ], had been battling each other for the control of Medina for more than a century before ].<ref name="wattAus">Watt. al-Aus; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> With the pledges of al-Aqaba, which took place near ], Muhammad was accepted as the common leader of Medina by the Aws and Khazraj and he addressed this by establishing the ] upon his arrival; a document which regulated interactions between the different factions, including the Arabian Jews of Medina, to which the signatories agreed. This was a different role for him, as he was only a religious leader during his time in ]. The result was the eventual formation of a united community in ], as well as the political supremacy of Muhammad,<ref name="buhlm">Buhl; Welch. Muhammad; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref><ref>Watt (1974) pp. 93–96</ref> along with the beginning of a ten-year long diplomatic career.<!-- this is sourced, please be patient enough to read on a few sentences till you reach the refs at the end of the para -->{{citation needed|date=September 2023}}<!-- THIS IS NOW THE END OF THE PARAGRAPH (2023-09-13) --> | |||

| In the final years before his death, Muhammad established communication with other leaders through ],<ref name="isal">Irfan Shahid, ] to the end of the ], Journal of the ], Vol 106, No. 3, p.531</ref> ],<ref name="m412">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 412</ref> or by visiting them personally, ];<ref name="w81">Watt (1974) p. 81</ref> Muhammad intended to spread the message of Islam outside of Arabia. Instances of preserved written correspondence include letters to ], the ] and ], among other leaders. Although it is likely that Muhammad had initiated contact with other leaders within the ], some have questioned whether letters had been sent beyond these boundaries.<ref name="f28">Forward (1998) pp. 28–29</ref> | |||

| Muhammad also participated in agreements and pledges such as "Pledges of al-`Aqaba", the ], and the "Pledge under the Tree". He reportedly used a silver ] on letters sent to other notable leaders who were ].<ref name="m412">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 412</ref><ref name="buhlm"/><ref>Haykal (1993) Section: "The Prophet's Delegates"</ref> | |||

| The main defining moments of Muhammad's career as a diplomat are the ], the ], and the ]. Muhammad reportedly used a silver ] on letters sent to other notable leaders which he sent as ].<ref name="m412" /><ref name="buhlm" /><ref></ref> | |||

| ==Muslim migration to Abyssinia (615)== | |||

| Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading ] of ], the ]. Although Muhammad himself was safe from persecution due to protection from his uncle, ] (a leader of ]), some of his followers were not in such a position. A number of Muslims were mistreated by the Quraish, some reportedly beaten, imprisoned, or starved.<ref>Forward (1998) p. 14</ref><!--mention Bilal (as per ref ibid.) or no?--> It was then, in ], that Muhammad resolved to send fifteen Muslims to emigrate to ] to receive protection under the ] ruler, the ].<ref name="f15">Forward (1998) p. 15</ref> Emigration was a means through which some of the Muslims could escape the difficulties and persecution faced at the hands of the Quraish,<ref name="buhlm"/> although it also opened up new trading prospects.<ref>Watt (1974) pp. 67—68</ref> | |||

| ]).]] | |||

| Quraish, on hearing the attempted emigration, dispatched a group led by ] and Abdullah ibn Abi Rabia ibn Mughira in order to pursue the fleeing Muslims. They were unsuccessful in their chase however as the Muslims had already reached safe territory, and so approached the Negus (named ''Ashmaha''), appealing to him to return the Muslim migrants. Summoned to an audience with the Negus and his bishops as a representative of Muhammad and the Muslims, ] spoke of Muhammad's achievements and quoted ] related to Islam and ], including some from ].<ref name="donzelencnaj">van Donzel. al-Nadjāshī; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref><ref>Ja'far is quoted according to ] as saying, "O king! We were plunged in the depth of ignorance and barbarism; we adored ]s, we lived in unchastity, we ate the dead bodies, and we spoke abominations, we disregarded every feeling of humanity, and the duties of hospitality and neighbourhood were neglected; we knew no law but that of the strong, when Allah raised among us a man, of whose birth, truthfulness, honesty, and purity we were aware; and he called to the Oneness of Allah and taught us not to associate anything with Him. He forbade us the worship of idols; and he enjoined us to speak the truth, to be faithful to our trusts, to be merciful and to regard the rights of the neighbours and kith and kin; he forbade us to speak evil of women, or to eat the substance of orphans; he ordered us to fly from the vices, and to abstain from evil; to offer prayers, to render alms, and to observe fast. We have believed in him, we have accepted his teachings and his injunctions to worship ] and not to associate anything with Him, and we have allowed what He has allowed, and prohibited what He has prohibited. For this reason, our people have risen against us, have persecuted us in order to make us forsake the worship of Allah and return to the worship of idols and other abominations. They have tortured and injured us, until finding no safety among them, we have come to your country, and hope you will protect us from oppression." Al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 121, Ibn Hisham, as-Seerat an-Nabawiyyah, Vol. I, pp. 334—338 </ref> | |||

| ==Early invitations to Islam== | |||

| The Negus, seemingly impressed, consequently allowed the migrants to stay, sending back the emissaries of Quraish.<ref name="donzelencnaj"/> It is also thought that the Negus may have converted to Islam.<ref>Vaglieri. Dja'far b. Abī Tālib; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> The Christian subjects of the Negus were displeased with his actions, accusing him of leaving Christianity, although the Negus managed to appease them in a way which, according to ], could be described as favourable towards Islam.<ref name="donzelencnaj"/> Having established friendly relations with the Negus, it became possible for Muhammad to send another group of migrants, such that the number of Muslims living in Abyssinia totalled around one hundred.<ref name="f15"/> | |||

| {{Main|Migration to Abyssinia}} | |||

| == |

=== Migration to Abyssinia === | ||

| ]]] | |||

| In early June ], Muhammad set out from Mecca to travel to the town of ] in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of ] (such as ]).<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 162</ref> The main dialogue during this visit is thought to have been the invitation by Muhammad for them to accept Islam, while contemporary historian ] observes the plausibility of an additional discussion about wresting Ta'if trade routes from Meccan control.<ref name="w81"/> The reason for Muhammad directing his efforts towards at-Ta'if may have been due to the lack of positive response from the people of Mecca to his message until then.<ref name="buhlm"/> | |||

| Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading ] of Mecca, the ]. Although Muhammad himself was safe from persecution due to protection from his uncle, ], a leader of the ], one of the main clans that formed the Quraysh), some of his followers were not in such a position. Several Muslims were mistreated by the Quraysh; some were reportedly beaten, imprisoned, or starved.<ref>Forward (1998) p. 14</ref> In 615, Muhammad resolved to send fifteen Muslims to emigrate to the ] to receive protection under the ] ruler called the ] in Muslim sources.<ref name="f15">Forward (1998) p. 15</ref> Emigration was a means through which some of the Muslims could escape the difficulties and persecution faced at the hands of the Quraysh<ref name="buhlm" /> and it also opened up new trading prospects.<ref>Watt (1974) pp. 67–68</ref> | |||

| === Ja'far ibn Abu Talib as Muhammad's ambassador === | |||

| ]).]] | |||

| The Quraysh, on hearing the attempted emigration, dispatched a group led by ] and Abdullah ibn Abi Rabi'a ibn Mughira in order to pursue the fleeing Muslims. The Muslims reached Axum before they could capture them, and were able to seek the safety of the Negus in ]. The Qurayshis appealed to the Negus to return the Muslims and they were summoned to an audience with the Negus and his bishops as a representative of Muhammad and the Muslims, ] acted as the ambassador of the Muslims and spoke of Muhammad's achievements and quoted ] related to Islam and ], including some from ].<ref name="donzelencnaj">van Donzel. al-Nadjāshī; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> | |||

| The Negus, seemingly impressed, consequently allowed the migrants to stay, sending back the emissaries of Quraysh.<ref name="donzelencnaj"/> It is also thought that the Negus may have converted to Islam.<ref>Vaglieri. Dja'far b. Abī Tālib; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> The Christian subjects of the Negus were displeased with his actions, accusing him of leaving Christianity, although the Negus managed to appease them in a way which, according to ], could be described as favourable towards Islam.<ref name="donzelencnaj"/> Having established friendly relations with the Negus, it became possible for Muhammad to send another group of migrants, such that the number of Muslims living in Abyssinia totalled around one hundred.<ref name="f15"/> | |||

| === Pre-Hijra invitations to Islam === | |||

| In rejection of his message, and fearing that there would be reprisals from Mecca for having hosted Muhammad, the groups involved in meeting with Muhammad began to incite townfolk to pelt him with stones.<ref name="w81"/> Having been beset and pursued out of at-Ta'if, the wounded Muhammad sought refuge in a nearby ].<ref>Muir (1861) Vol. II p. 200</ref> Resting under a ], it is here that he invoked ], seeking comfort and protection.<ref name="mtaif">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 163—166</ref><ref>Muir (1861) Vol. II p. 202</ref> | |||

| ====Ta'if==== | |||

| According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad on his way back to Mecca was met by the angel ] and the angels of the mountains surrounding at-Ta'if, and was told by them that if he willed, at-Ta'if would be crushed between the mountains in revenge for his mistreatment. Muhammad is said to have rejected the proposition, saying that he would pray in the hopes of preceding generations of at-Ta'if coming to accept Islamic monotheism.<ref name="mtaif"/><ref>] , ] </ref> | |||

| ] in the background (])]] | |||

| In early June 619, Muhammad set out from Mecca to ] in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of ] (such as ]).<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 162</ref> The main dialogue during this visit is thought to have been the invitation by Muhammad for them to accept Islam, while contemporary historian ] observes the plausibility of an additional discussion about wresting the Meccan ]s that passed through Ta'if from Meccan control.<ref name="w81" /> The reason for Muhammad directing his efforts towards Ta'if may have been due to the lack of positive response from the people of Mecca to his message until then.<ref name="buhlm" /> | |||

| In rejection of his message, and fearing that there would be reprisals from Mecca for having hosted Muhammad, the groups involved in meeting with Muhammad began to incite townsfolk to pelt him with stones.<ref name="w81" /> Having been beset and pursued out of Ta'if, the wounded Muhammad sought refuge in a nearby ].<ref>Muir (1861) Vol. II p. 200</ref> Resting under a ], it is here that he invoked ], seeking comfort and protection.<ref name="mtaif">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 163–166</ref><ref>Muir (1861) Vol. II p. 202</ref> | |||

| ==al-`Aqaba pledges (620—621)== | |||

| In the summer of ] during the pilgrimage season, six men travelling from ] came into contact with Muhammad. Having been impressed by his message and character, and thinking that he could help bring resolution to the problems being faced in Medina, five of the six men returned to Mecca the following year bringing seven others. Following their acceptance of Islam and of Muhammad as the messenger of Allah, the twelve men pledged to obey him and to stay away from a number of sinful acts. This was known as the "''First Pledge of al-`Aqaba''."<ref name="watt83">Watt (1974) p. 83</ref> | |||

| According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad on his way back to Mecca was met by the ] ] and the angels of the mountains surrounding Ta'if, and was told by them that if he willed, Ta'if would be crushed between the mountains in revenge for his mistreatment. Muhammad is said to have rejected the proposition, saying that he would pray in the hopes of succeeding generations of Ta'if coming to accept ].<ref name="mtaif"/><ref>] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100526072029/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/054.sbt.html |date=2010-05-26 }}, ] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100820122650/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muslim/019.smt.html#019.4425 |date=2010-08-20 }}</ref> | |||

| Following the pledge, Muhammad decided to send a Muslim "ambassador", ], to Medina in order to teach people about Islam and invite them to it.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 187</ref> Converts to Islam came from nearly all ] tribes present in Medina, such that by June of the subsequent year there were seventy-five Muslims coming to Mecca for pilgrimage and to meet Muhammad. Meeting him secretly by night, the group made what was known as the "''Second Pledge of al-`Aqaba''", or the "''Pledge of War''".<ref name="watt83"/> Conditions of the pledge, many of which similar to the first, included obedience to Muhammad, "enjoining good and forbidding evil" as well as responding to the call to arms when required.<ref>Ibn Hisham, as-Seerat an-Nabawiyyah, Vol. I p. 454</ref> | |||

| ====Pledges at al-'Aqaba==== | |||

| Some western academics are noted to have questioned whether or not a second pledge had taken place, although Watt argues that there must have been several meetings between the pilgrims and Muhammad on which the basis of his move to Medina could be agreed upon.<ref>Watt (1974) p. 84</ref> | |||

| {{main|Second pledge at al-Aqabah}} | |||

| ]'' pilgrims at ]]] | |||

| In the summer of 620 during the pilgrimage season, six men of the ] travelling from Medina came into contact with Muhammad. Having been impressed by his message and character, and thinking that he could help bring resolution to the problems being faced in Medina, five of the six men returned to Mecca the following year bringing seven others. Following their ] and attested belief in Muhammad as the messenger of God, the twelve men pledged to obey him and to stay away from a number of Islamically sinful acts. This is known as the ''First Pledge of al-'Aqaba'' by Islamic historians.<ref name="watt83">Watt (1974) p. 83</ref> Following the pledge, Muhammad decided to dispatch a Muslim ambassador to Medina and he chose ] for the position, in order to teach people about Islam and invite them to the religion.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 187</ref> | |||

| With the slow but steady conversion of persons from both the Aws and Khazraj present in ], 75 Medinan Muslims came as pilgrims to Mecca and secretly convened with Muhammad in June 621, meeting him at night. The group made to Muhammad the ''Second Pledge of al-'Aqaba'', also known as the ''Pledge of War''.<ref name="watt83" /> The people of Medina agreed to the conditions of the first pledge, with new conditions including included obedience to Muhammad, the ]. They also agreed to help Muhammad in war and asked of him to declare war on the Meccans, but he refused.<ref>Ibn Hisham, as-Seerat an-Nabawiyyah, Vol. I p. 454</ref> | |||

| ==Reformation of Medina (622—)== | |||

| ===Medinan society prior to Muslim migration=== | |||

| Some western academics are noted to have questioned whether or not a second pledge had taken place, although ] argues that there must have been several meetings between the pilgrims and Muhammad on which the basis of his move to Medina could be agreed upon.<ref>Watt (1974) p. 84</ref> | |||

| The demography of Medina before Muslim migration consisted mainly of two pagan Arab tribes; the ] and the ]; and at least three ] tribes: ], ], and ].<ref name="buhlm"/> Medinan society, for perhaps decades, had been scarred by fueds between the two main Arab tribes and their sub-clans. The Jewish tribes had at times formed their own alliances with either one of the Arab tribes. The oppressive policy of the Khazraj who at the time had assumed control over Medina, forced the Jewish tribes Nadir and Qurayza into alliance with the Aws who had been significantly weakened. The culmination of this was the ] in ], in which the Khazraj and their allies, Qaynuqa, has been soundly defeated by the coalition of Aws and its supporters.<ref name="wattaws"><ref>Bosworth. Bu'ā<u>th</u>; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> | |||

| ==Muhammad as the leader of Medina== | |||

| Although formal combat between the two clans had ended, hostilities between them continued even up until Muhammad's arrival in Medina. Muhammad had been invited by some Medinans, who had been impressed by his religious preaching and apparent trustworthiness, as an arbitrator to help reduce the prevailing factional discord.<ref name="f19">Forward (1998) p. 19</ref> Muhammad's task would thus be to form a united community out of these heterogeneous elements, not only as a religious preacher, but as a political and diplomatic leader who could help resolve the ongoing disputes.<ref name="buhlm"/> | |||

| {{See also|Muhammad in Medina}} | |||

| ===Pre-Hijra Medinan society=== | |||

| The demography of Medina before Muslim migration consisted mainly of two ] ] tribes; the ] and the ]; and at least three ] tribes: the ], ], and ].<ref name="buhlm" /> Medinan society, for perhaps decades, had been scarred by feuds between the two main Arab tribes and their sub-clans. The ] had at times formed their own alliances with either one of the Arab tribes. The oppressive policy of the Khazraj who at the time had assumed control over Medina, forced the Jewish tribes, Nadir and Qurayza, into an alliance with the Aws, who had been significantly weakened. The culmination of this was the ] in 617, in which the Khazraj and their allies, the Qaynuqa, had been soundly defeated by the coalition of Aws and its supporters.<ref name="wattAus" /><ref>Bosworth. Bu'ā<u>th</u>; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> | |||

| Although formal combat between the two clans had ended, hostilities between them continued even up until Muhammad's arrival in Medina. Muhammad had been invited by some Medinans, who had been impressed by his religious preaching and manifest trustworthiness, as an arbitrator to help reduce the prevailing factional discord.<ref name="f19">Forward (1998) p. 19</ref> Muhammad's task would thus be to form a united community out of these heterogeneous elements, not only as a religious preacher, but as a political and diplomatic leader who could help resolve the ongoing disputes.<ref name="buhlm" /> The culmination of this was the ]. | |||

| ===Constitution of Medina=== | ===Constitution of Medina=== | ||

| {{main|Constitution of Medina}}{{wikisource|Constitution of Medina}}After the pledges at al-'Aqaba, Muhammad received promises of protection from the people of Medina and he ] with a group of his ] in 622, having escaped the forces of Quraysh. They were given shelter by members of the indigenous community known as the ]. After having established the first ] in Medina (the ]) and obtaining residence with ],<ref>Ibn Kathir, al-Bidaayah wa an-Nihaayah, Vol. II, p. 279.</ref> he set about the establishment of a pact known as the ] ({{Langx|ar|صحيفة المدينة|translit=Sahifat ul-Madinah|lit=Charter of Medina}}). This document was a unilateral declaration by Muhammad, and deals almost exclusively with the civil and political relations of the citizens among themselves and with the outside.<ref name="bl43">Bernard Lewis, ''The Arabs in History,'' page 43.</ref> | |||

| The Constitution, among other terms, declared: | |||

| * the formation of a nation of Muslims ('']'') consisting of the '']'' from the ], the ] of Yathrib (]) and other Muslims of Yathrib. | |||

| Significant clauses of the constitution included the mutual assistance of each other if one signatory were to be attacked by a third party, the resolution that the Muslims would profess their religion and the Jews theirs, as well as the appointment of Muhammad as the leader of the state.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p.230</ref> It is argued however that Muhammad's authority had not extended over the entirety of Medina at this time, such that in reality he was only the religious leader of Medina, and his political influence would only become significant after the ] in ].<ref>Watt (1974) pp. 95, 96</ref> ] opines that Muhammad's assumption of the role of statesman was a means through which he could achieve his religious objectives.<ref>Lewis (1984) p. 12</ref> The constitution, although recently signed, was soon to be rendered obsolete due to the rapidly changing conditions in Medina,<ref name="buhlm"/> with certain tribes having been accused of breaching the terms of agreement.<!--needs expansion--> | |||

| * the establishment of a system of prisoner exchange in which the rich were no longer treated differently from the poor (as was the custom in ]) | |||

| * all the signatories would unite as one in the defense of the city of Medina, declared the Jews of Aws equal to the Muslims, as long as they were loyal to the charter. | |||

| * the protection of Jews from ] | |||

| * that the declaration of war can only be made by ]. | |||

| ===Impact=== | ====Impact of the Constitution==== | ||

| The source of authority was transferred from public opinion to God.<ref name="bl43" /> ] writes the community at Medina became a new kind of tribe with Muhammad as its ], while at the same time having a religious character.<ref>Lewis, page 44.</ref> Watt argues that Muhammad's authority had not extended over the entirety of Medina at this time, such that in reality he was only the religious leader of Medina, and his political influence would only become significant after the ] in 624.<ref>Watt (1974) pp. 95, 96</ref> Lewis opines that Muhammad's assumption of the role of statesman was a means through which the objectives of ] could be achieved.<ref>Lewis (1984) p. 12</ref> The constitution, although recently signed, was soon to be rendered obsolete due to the rapidly changing conditions in Medina,<ref name="buhlm" /> and with the exile of two of the Jewish tribes and the execution of the third after having been accused of breaching the terms of agreement. | |||

| The signing of the constitution could be seen as indicating the formation of a united community, in ways similar to a ] of ] clans and tribes, as the signatories were bound together by solemn agreement. The community, however, now also had a religious basis.<ref name="w945">Watt (1974) p. 94—95</ref> Extending this analogy, Watt argues that the functioning of the community resembled that of a tribe, such that it would not be incorrect to call the community a kind of "super-tribe".<ref name="w945"/> The signing of the constitution itself displayed a degree of diplomacy by Muhammad, as although he envisioned a society eventually based upon a religious outlook, practical consideration was needed to be inclusive instead of exclusive of the varying social elements.<ref name="buhlm"/> | |||

| The signing of the constitution could be seen as indicating the formation of a united community, in many ways, similar to a ] of ]ic clans and tribes, as the signatories were bound together by solemn agreement. The community, however, now also had a ].<ref name="w945">Watt (1974) pp. 94–95</ref> Extending this analogy, Watt argues that the functioning of the community resembled that of a tribe, such that it would not be incorrect to call the community a kind of "super-tribe".<ref name="w945" /> The signing of the constitution itself displayed a degree of diplomacy on part of Muhammad, as although he envisioned a society eventually based upon a religious outlook, practical consideration was needed to be inclusive instead of exclusive of the varying social elements.<ref name="buhlm" /> | |||

| Both the Aws and Khazraj had progressively converted to Islam, although the latter had been more enthusiastic than the former: at the second pledge of al-`Aqaba, the numbers of Khazraj to Aws present was 62:3; and at the Battle of Badr, 175:63.<ref>Watt. <u>Kh</u>azradj; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> Subsequently, the hostility between the Aws and Khazraj gradually diminished and became unheard of after Muhammad's death.<ref name="wattaws"/> | |||

| ==== Union of the Aws and Khazraj ==== | |||

| The result was Muhammad's increasing influence in Medina, although he was most probably only considered a political force after the Battle of Badr, more so after the ] where he was clearly in political ascendency.<ref>Watt (1974) p. 96</ref> To attain complete control over Medina, Muhammad would have to exercise considerable political, military as well as religious skills over the coming years.<ref name="f19"/> | |||

| Both the ] and ] had progressively converted to Islam, although the latter had been more enthusiastic than the former; at the second pledge of al-'Aqaba, 62 Khazrajis were present, in contrast to the three members of the Aws; and at the Battle of Badr, 175 members of the Khazraj were present, while the Aws numbered only 63.<ref>Watt. <u>Kh</u>azradj; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> Subsequently, the hostility between the Aws and Khazraj gradually diminished and became unheard of after Muhammad's death.<ref name="wattAus" /> According to ] ], the 'spirit of brotherhood' as insisted by Muhammad amongst Muslims was the means through which a new society would be shaped.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 227–229</ref> | |||

| The result was Muhammad's increasing influence in Medina, although he was most probably only considered a political force after the Battle of Badr, more so after the ] where he was clearly in political ascendency.<ref>Watt (1974) p. 96</ref> To attain complete control over Medina, Muhammad would have to exercise considerable political and ], alongside religious skills over the coming years.<ref name="f19" /> | |||

| ==Events at Hudaybiyya (628)== | |||

| In March ], Muhammad reportedly saw himself in a dream performing the '']'' (lesser pilgrimage<ref>Journey to Mecca performed by Muslims during which they perform rites such as circumambulation ('']'') of the ] and briskly walking back and forth between the hills of ]. The "''Umrah''" is not to be confused with "'']''", which is regarded as the greater pilgrimage.</ref>), and so prepared to travel with his followers to Mecca in the hopes of fulfilling this vision. He set out with a group of around 1,400 pilgrims (in the traditional ]<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 398</ref>), although it was not soon until Mecca had discovered these arrangements. On hearing of the Muslims travelling to Mecca for pilgrimage, the Quraish sent out a force of 200 fighters in order to halt the approaching party. In no position to fight, Muhammad evaded the cavalry by taking a more difficult route, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just outside of Mecca.<ref name="watthudenc">Watt. al-Hudaybiya; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> | |||

| === Treaty of Hudaybiyyah === | |||

| It was at Hudaybiyya that a number of envoys went to and fro in order to negotiate with the Quraish. During the negotiations, ] was chosen as an envoy to convene with the leaders in Mecca, on account of his high regard amongst the Quraish.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 402</ref> On his entry into Mecca, rumours ignited that Uthman had subsequently been murdered by the Quraish. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "''Pledge of Good Pleasure''" (]: بيعة الرضوان , ''bay'at al-ridhwān'') or the "''Pledge under the Tree''". <ref name="watthudenc"/><ref>] {{Quran-usc|48|18}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Treaty of Hudaybiyyah}} | |||

| ==== Muhammad's attempt at performing the 'Umrah ==== | |||

| ===Treaty=== | |||

| In March 628, Muhammad saw himself in a dream performing the '']'' (lesser pilgrimage),<ref>Journey to Mecca performed by Muslims during which they perform rites such as circumambulation ('']'') of the ] and briskly walking back and forth between the hills of ]. The "''Umrah''" is not to be confused with "'']''", which is regarded as the greater pilgrimage.</ref> and so prepared to travel with his followers to Mecca in the hopes of fulfilling this vision. ] with a group of around 1,400 pilgrims (in the traditional ]<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 398</ref>). On hearing of the Muslims travelling to Mecca for pilgrimage, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 fighters in order to halt the approaching party. In no position to fight, Muhammad evaded the cavalry by taking a more difficult route through the hills north of ], thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just west of Mecca.<ref name="watthudenc">Watt. al-Hudaybiya; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> | |||

| {{main|Treaty of Hudaybiyya}} | |||

| It was at Hudaybiyyah that a number of envoys went to and fro in order to negotiate with the Quraysh. During the negotiations, ] was chosen as an envoy to convene with the leaders in Mecca, on account of his high regard amongst the Quraysh.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 402</ref> On his entry into Mecca, rumours ignited among the Muslims that 'Uthman had subsequently been murdered by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the ''Pledge of Good Pleasure'' ({{Langx|ar|بيعة الرضوان|translit=Bay'at ar-Ridhwān|lit=}}) or the ''Pledge Under The Tree''.<ref name="watthudenc" /> | |||

| Soon afterwards, with the rumour of Uthman's slaying proven untrue, negotiations continued and a treaty was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraish. Conditions of the treaty included the Muslims' postponement of the lesser pilgrimage until the following year, a pact of mutual non-aggression between the parties, and a promise by Muhammad to return any member of Quraish (presumably a minor or woman) fleeing from Mecca without the permission of their parent or guardian, even if they be Muslim.<ref>Forward (1998) p. 28</ref> Some of Muhammad's followers were upset by this agreement, as they had insisted that they should complete the pilgrimage they had set out for. Following the signing of the treaty, Muhammad and the pilgrims ] the animals they had brought for it, and proceeded to return to Medina.<ref name="watthudenc"/> It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty.<ref name="buhlm"/> These benefits, according to Islamic historian Buhl, included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity posing well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.<ref name="buhlm"/> | |||

| The incident was mentioned in the ] in Surah 48:<ref name="watthudenc" /> | |||

| The treaty was set to expire after 10 years, but was broken after only 10 months,<ref name="watthudenc"/> due to a perceived violation of the treaty when a Meccan had murdered a Muslim.<ref name="f29"> Forward (1998) p. 29</ref> Other sources suggest that the violation was due to the Meccans' aiding of a client clan against a tribal ally of Muhammad.<ref name="buhlm"/><!-- "other" because it's probably not only the EoI which forwards this view --> The reaction was the assembly of an army of ten thousand men by Muhammad to march unto Mecca, resulting in the ].<ref name="f29"/> | |||

| {{blockquote|Allah's Good Pleasure was on the Believers when they swore Fealty to thee under the Tree: He knew what was in their hearts, and He sent down Tranquillity to them; and He rewarded them with a speedy Victory;|Translated by ]|] 48 (]), ayah 18<ref>{{cite quran|48|18|s=ns}}</ref>}} | |||

| ==Correspondence with other leaders== | |||

| ====Signing of the Treaty==== | |||

| {{quotefarm}} | |||

| Soon afterwards, with the rumour of Uthman's slaying proven untrue, negotiations continued and a treaty was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh. Conditions of the treaty included:<ref>Forward (1998) p. 28</ref> | |||

| * the Muslims' postponement of the lesser pilgrimage until the following year | |||

| ] | |||

| * a pact of mutual non-aggression between the parties | |||

| There are instances according to Islamic tradition where Muhammad is thought to have sent letters to other heads of state during the Medinan phase of his life. Personalities, amongst others, included the ] of ], ] (emperor of ]), the ] of ], the ] of ]. There has been great controversy amongst academic scholars as to their authenticity.<ref name="Nadia">El-Cheikh (1999) pp. 5—21</ref> According to ], academics have treated some reports with scepticism, although he argues that it is likely that Muhammad had assumed correspondence with leaders within the Arabian peninsula.<ref name="f28"/> R.B. Serjeant <!-- need to mention exactly who he is preferably --> opines that the letters are forgeries and were designed to promote both the 'notion that Muhammad conceived of Islam as a universal religion and to strengthen the Islamic position against Christian polemic.' He further argues the unlikelihood of Muhammad sending such letters when he had not yet mastered Arabia.<ref> Footnote of the El-Cheikh(1999) reads: "Opposed to its authenticity is R. B. Sejeant "Early Arabic Prose: in Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period, ed. A. E L. Beeston et a1 ... (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 141-2. Suhaila aljaburi also doubts the authenticity of the document; "Ridlat al-nabi ila hiraql malik al-~m,H" amdard Islamicus 1 (1978) no. 3, pp. 15-49"</ref><ref>Serjeant also draws the attention to anachronisms such as the mention of the payment of the poll tax. ''Loc cit.''</ref> Irfan Shahid, professor of Arabic and Islamic literature at ], contends that dismissing the letters sent by Muhammad as forgeries is "unjustified", pointing to recent research establishing the historicity of the letter to Heraclius as an example.<ref name="isal"/> | |||

| * a promise by Muhammad to return any member of Quraysh (presumably a minor or woman) fleeing from Mecca without the permission of their parent or guardian, even if they be Muslim. | |||

| Some of Muhammad's followers were upset by this agreement, as they had insisted that they should complete the pilgrimage they had set out for. Following the signing of the treaty, Muhammad and the pilgrims ] the animals they had brought for it, and proceeded to return to Medina.<ref name="watthudenc" /> It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty.<ref name="buhlm" /> These benefits, according to Islamic historian Welch Buhl, included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity, boding well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.<ref name="buhlm" />{{Campaignbox Campaigns of Muhammad}} | |||

| ===Letter to Heraclius=== | |||

| ==== Violation of the Treaty ==== | |||

| A letter was sent from Muhammad to the emperor of Byzantium, Heraclius, through the Muslim envoy ], although Irfan Shahid suggests that Heraclius may never have received it.<ref name="isal"/> It also advances that more positive sub-narratives surrounding the letter contain little credence. According to El-Cheikh, Arab historians and chroniclers generally did not doubt the authenticity of Heraclius' letter due to the documentation of such letters in the majority of both early and later sources.<ref name="Nadia"/> Furthermore, she notes that the formulation and the wordings of different sources are very close and the differences are ones of detail: They concern the date on which the letter was sent and its exact phrasing.<ref name="Nadia"/> ], an Islamic research scholar, argues for the authenticity of the letter sent to Heraclius, and in a later work reproduces what is claimed to be the original letter.<ref name="Nadia" /><ref> Footnote of the El-Cheikh(1999) reads: "Hamidullah discussed this controversy and tried to prove the authenticity of Heraclius' letter in his "La lettre du Prophete P Heraclius et le sort de I'original: Arabica 2(1955), pp. 97-1 10, and more recently, in Sir originaw des lettms du prophbte de I'lslam (Paris, 1985), pp. 149.172, in which he reproduces what purports to be the original letter."</ref> The account as transmitted by Muslim historians reads as follows<ref name="Nadia"> Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5-21. </ref>: | |||

| The treaty was set to expire after 10 years, but was broken after only 10 months.<ref name="watthudenc" /> According to the terms of the treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the Arab tribes were given the option to join either of the parties, the Muslims or Quraish. Should any of these tribes face aggression, the party to which it was allied would have the right to retaliate. As a consequence, ] joined Quraish, and the ] joined Muhammed.{{sfnp|al-Mubarakpuri|2002|p={{page needed|date=September 2023}}}} Banu Bakr attacked ]h at al-Wateer in Sha'baan 8 AH and it was revealed that the Quraish helped Banu Bakr with men and arms taking advantage of the cover of the night.{{sfnp|al-Mubarakpuri|2002|p={{page needed|date=September 2023}}}} Pressed by their enemies, the tribesmen of Khuza‘ah sought the ], but here too, their lives were not spared, and Nawfal, the chief of Banu Bakr, chasing them in the sanctified area, massacred his adversaries. | |||

| ==Correspondence with other leaders== | |||

| ]{{cquote|In the name of Allah the Beneficent, the Merciful | |||

| There are instances according to Islamic tradition where Muhammad is thought to have sent letters to other heads of state during the ] of his life. Amongst others, these included the ] of ], the ] ] ({{Reign|610|641}}), the '']'' of ] and the ] ] ({{Reign|590|628}}). There has been controversy amongst academic scholars as to their authenticity.<ref name="ElCheikh5">El-Cheikh (1999) pp. 5–21</ref> According to ], academics have treated some reports with ], although he argues that it is likely that ] had assumed correspondence with leaders within the ].<ref name="f28"/> ] opines that the letters are forgeries and were designed to promote both the 'notion that Muhammad conceived of Islam as a universal religion and to strengthen the Islamic position against Christian polemic.' He further argues the unlikelihood of Muhammad sending such letters when he had not yet mastered Arabia.<ref>Footnote of the El-Cheikh (1999) reads: "Opposed to its authenticity is R. B. Sejeant "Early Arabic Prose: in Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period, ed. A. E L. Beeston et a1 ... (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 141–2. Suhaila aljaburi also doubts the authenticity of the document; "Ridlat al-nabi ila hiraql malik al-~m,H" amdard Islamicus 1 (1978) no. 3, pp. 15–49"</ref><ref>Serjeant also drAus the attention to anachronisms such as the mention of the payment of ]. ''Loc cit.''</ref> ], professor of the ] and ] at ], contends that dismissing the letters sent by Muhammad as forgeries is "unjustified", pointing to recent research establishing the historicity of the letter to ] as an example.<ref name="isal"/> | |||

| ===Letter to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire=== | |||

| (This letter is) from Muhammad the slave of Allah and His Apostle to Heraclius the ruler of Byzantine. | |||

| {{see also|Expedition of Zaid ibn Haritha (Hisma)}} | |||

| ]; reproduction taken from Majid Ali Khan, ''Muhammad The Final Messenger'' Islamic Book Service, New Delhi (1998).]] | |||

| ] | |||

| A letter was sent from Muhammad to the emperor of the ], ], through the Muslim envoy ], although ] suggests that Heraclius may never have received it.<ref name="isal"/> He also advances that more positive sub-narratives surrounding the letter contain little credence. According to Nadia El Cheikh, Arab historians and chroniclers generally did not doubt the authenticity of Heraclius' letter due to the documentation of such letters in the majority of both early and later sources.<ref name="Nadia">Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5–21.</ref> Furthermore, she notes that the formulation and the wordings of different sources are very close and the differences are ones of detail: They concern the date on which the letter was sent and its exact phrasing.<ref name="Nadia"/> ], an Islamic research scholar, argues for the authenticity of the letter sent to Heraclius, and in a later work reproduces what is claimed to be the original letter.<ref name="Nadia" /><ref>Footnote of the El-Cheikh (1999) reads: "Hamidullah discussed this controversy and tried to prove the authenticity of Heraclius' letter in his "La lettre du Prophete P Heraclius et le sort de I'original: Arabica 2(1955), pp. 97–1 10, and more recently, in Sir originaw des lettms du prophbte de I'lslam (Paris, 1985), pp. 149.172, in which he reproduces what purports to be the original letter."</ref> | |||

| The account as transmitted by ] is translated as follows:<ref name="Nadia" /> | |||

| Peace be upon him, who follows the right path. Furthermore I invite you to Islam, and if you become a Muslim you will be safe, and Allah will double your reward, and if you reject this invitation of Islam you will be committing a sin by misguiding your Arisiyin (peasants). (And I recite to you Allah's Statement:) | |||

| {{Blockquote|]<br/>From Muhammad, servant of God and His apostle to Heraclius, premier of the Romans:<br/>Peace unto whoever follows the guided path!<br/>Thereafter, verily I call you to submit your will to God. Submit your will to God and you will be safe. God shall compensate your reward two-folds. But if you turn away, then upon you will be the sins of The Arians.<br/>Then "O ], come to a term equitable between us and you that we worship none but God and associate with Him nothing, and we take not one another as Lords apart from God. But if they turn away, then say: Bear witness that we peace makers."{{cite quran|3|64}}<br/>]: Muhammad, Apostle of God}} | |||

| ''"Say (O Muhammad): 'O people of the scripture! Come to a word common to you and us that we worship none but Allah and that we associate nothing in worship with Him, and that none of us shall take others as Lords beside Allah.' Then, if they turn away, say: 'Bear witness that we are Muslims' (those who have surrendered to Allah)." (3:64)''<ref name="Nadia"> Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5-21. </ref><ref name="bukhariherac">Sahih Bukhari </ref>}} | |||

| According to Islamic reports, Muhammad dispatched ]<ref name=bukhari>{{cite web |title=Sahih al-Bukhari 2940, 2941 - Fighting for the Cause of Allah (Jihaad) - كتاب الجهاد والسير |url=https://sunnah.com/bukhari:2940 |website=sunnah.com |publisher=Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم) |access-date=18 August 2021}}</ref><ref name="al-islam.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.al-islam.org/message/43.htm|title=The Events of the Seventh Year of Migration - The Message|website=www.al-islam.org |publisher=Al-Islam.org|access-date=25 August 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120805184742/http://www.al-islam.org/message/43.htm|archive-date=5 August 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> to carry the epistle to "]" through the government of ] after the ].<ref name=sirat2>{{cite book |last1=Guillaume |first1=A. |title=Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah - The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume |date=1955 |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=https://archive.org/details/TheLifeOfMohammedGuillaume}}</ref><ref name=mishkat>{{cite web |title=Mishkat al-Masabih 3926 - Jihad - كتاب الجهاد |url=https://sunnah.com/mishkat:3926 |website=sunnah.com |publisher=Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم) |access-date=19 August 2021}}</ref><ref name=bukhari/> Islamic sources say that after the letter was read to him, he was so impressed by it that he gifted the messenger of the epistle with robes and coinage.<ref name=moon>{{Cite book|title=When the Moon Split (A Biography of Prophet Muhammad)|last=Mubarakpuri|first=Safi ar-Rahman|author-link=Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri |publisher=Darussalam Publications|year=2002|isbn=978-603-500-060-4|location=|pages=}}</ref> Alternatively, he also put it on his lap.<ref name=sirat2/> He then summoned ] to his court, at the time an adversary to Muhammad but a signatory to the then-recent ], who was trading in the ] at the time. Asked by Heraclius about the man claiming to be a prophet, Abu Sufyan responded, speaking favorably of Muhammad's character and lineage and outlining some directives of Islam. Heraclius was seemingly impressed by what he was told of Muhammad, and felt that Muhammad's claim to prophethood was valid.<ref name="Nadia" /><ref name="bukhariherac">{{Hadith-usc|bukhari|usc=yes|1|1|6}}</ref><ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 420</ref> Later reportedly he wrote to a certain religious official in ] to confirm if Muhammad's claim of prophethood was legitimate, only to receive a letter with a dismisive rejection from the council. Dissatisfied with the response, Heraclius then called upon the ] saying, "If you desire salvation and the orthodox way so that your empire remain firmly established, then follow this prophet".<ref name=moon/><ref>{{cite web |title=Sahih al-Bukhari 7 - Revelation - كتاب بدء الوحى |url=https://sunnah.com/bukhari:7 |website=sunnah.com |publisher=Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم) |access-date=19 August 2021}}</ref><ref name=sirat2/> Heraclius eventually decided against conversion but the envoy was returned to Medina with the felicitations of the emperor.{{sfnp|al-Mubarakpuri|2002|p={{page needed|date=September 2023}}}} | |||

| ], currently an adversary to Muhammad but a signatory to the recent ], was trading in ] when he was summoned to the court of Heraclius. Asked by Heraclius about the man claiming to be a prophet, Abu Sufyan responded, speaking favorably of Muhammad's character and lineage and outlining some directives of Islam. Heraclius was seemingly impressed by what he was told of Muhammad, and felt that Muhammad's claim to prophethood was valid.<ref name="Nadia"> Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5-21. </ref><ref name="bukhariherac"/><ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 420</ref> Despite this incident, it seems that Heraclius was more concerned with the current rift between the various Christian churches within his empire, and as a result did not convert to Islam.<ref name="Nadia"> Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy, Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, Studia Islamica, No. 89. (1999), pp. 5-21. </ref><ref>Rogerson (2003) p. 200</ref> | |||

| Scholarly historians disagree with this account, arguing that any such messengers would have received neither an imperial audience or recognition, and that there is no evidence outside of Islamic sources suggesting that Heraclius had any knowledge of Islam.<ref name=WEK>{{cite book |last1=Kaegi |first1=Walter Emil |title=Heraclius, emperor of Byzantium |date=2003 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge, U.K. |isbn=0-521-81459-6}}</ref> | |||

| ===Deputation to Abyssinia=== | |||

| The letter inviting the Negus to Islam had been sent by Amr bin Omayah ad-Damari, although it is not known if the letter had been sent with Ja'far on migration to Abyssinia or at a later date following the Treaty of Hudaibiyya. According to Hamidullah, the former may be more likely.<ref name="m412"/> The letter reads: | |||

| This letter is mentioned in Sahih Al Bukhari.<ref>https://sunnah.com/bukhari:2938 {{bare URL inline|date=February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|In the Name of Allah the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful. | |||

| ===Letter to the Negus of Axum=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The letter inviting ], the ] king of Ethiopia/Abyssinia, to Islam had been sent by ], although it is not known if the letter had been sent with ] on the ] or at a later date following the ]. According to Hamidullah, the former may be more likely.<ref name="m412" /> The letter is translated as: | |||

| {{Blockquote|In the name of God, the Gracious One, the Merciful<br/>From Muhammad, Apostle of God to the Negus, premier of the Abyssinians:<br/>Peace unto whoever follows the guided path!<br/>Thereafter, verily to you I make praise of God, but Whom there is no god, the King, the Holy One, the Peace, the Giver of Faith, the Giver of Security. And I bear witness that ] son of ] is the ] of God and His ] that He cast into the Virgin Mary, the immaculate the ], and she was impregnated with Jesus by His Spirit and His blow like how He created ] with His Hand. And I verily call you to the one God with no partner to Him, and adherence upon His obedience, and that you follow me and believe in that which came to me, I, in fact, am the Apostle of God and verily call you and your hosts toward God, Might and Majesty.<br/>And thus I have informed and sincerely admonished. So accept my sincere admonition. "And Peace unto whoever follows the guided path."{{cite quran|20|47}}<br/>Seal: Muhammad, Apostle of God}} | |||

| Having received the letter, the Negus was purported to accept Islam in a reply he wrote to Muhammad. According to Islamic tradition, the Muslims in Medina prayed the ] in absentia for the Negus |

Having received the letter, the ] was purported by some Muslim sources to accept Islam in a reply he wrote to Muhammad. According to Islamic tradition, the Muslims in Medina prayed the ] in absentia for the Negus upon his death. However, there is no evidence for these claims with even some Muslim historians questioning them.<ref>Sahih al-Bukhari {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110822230659/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/058.sbt.html#005.058.220 |date=2011-08-22 }}</ref> It is possible that another letter was sent to the successor of the late Negus.<ref name="m412" /> | ||

| This letter is mentioned in Sahih Muslim.<ref>https://sunnah.com/muslim:2092e {{bare URL inline|date=February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ===Letter to Muqawqas=== | |||

| ===Letter to the Muqawqis of Egypt=== | |||

| There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to Muqawqas. Some scholars such as ] consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and ] considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqas to be "''devoid of any historical value''".<ref name="ohrnberg">Öhrnberg; Mukawkis. Encyclopaedia of Islam.</ref> Muslim historians, in contrast, generally affirm the historicity of the reports. The purported text of the letter (sent by Hatib bin Abi Balta'a) according to Islamic tradition is as follows: | |||

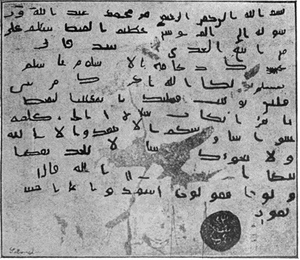

| ], which was discovered in Egypt in 1858<ref>"the original of the letter was discovered in 1858 by Monsieur Etienne Barthelemy, member of a French expedition, in a monastery in Egypt and is now carefully preserved in Constantinople. Several photographs of the letter have since been published. The first one was published in the well-known Egyptian newspaper Al-Hilal in November 1904" Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, ''Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets'', Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1980 (). The drawing of the letter published in Al-Hilal was reproduced in ], ''Mohammed and the Rise of Islam'', London (1905), </ref>]] | |||

| There has been conflict amongst scholars about the authenticity of aspects concerning the letter sent by Muhammad to ]. Some scholars such as ] consider the currently preserved copy to be a forgery, and Öhrnberg considers the whole narrative concerning the Muqawqis to be "devoid of any historical value".<ref name="ohrnberg">Öhrnberg; Mukawkis. Encyclopaedia of Islam.</ref> Muslim historians, in contrast, generally affirm the historicity of the reports. The text of the letter (sent by ]) according to Islamic tradition is translated as follows: | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| {{Blockquote|In the name of God, the Gracious One, the Merciful<br/>From Muhammad, servant of God and His apostle to al-Muqawqis, premier of Egypt:<br/>Peace unto whoever follows the guided path!<br/>And thereafter, verily I call you to the call of Submission ("Islam"). Submit (i.e., embrace Islam) and be safe God shall compensate your reward two-folds. But if you turn away, then upon you will be the guilt of the Egyptians.<br/>Then "O People of the Scripture, come to a term equitable between us and you that we worship none but God and associate with Him nothing, and we take not one another as Lords apart from God. But if they turn away, then say: Bear witness that we are Submitters ("Muslims")."{{cite quran|3|64}}<br/>Seal: Muhammad, Apostle of God<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 415</ref>}} | |||

| {{cquote|In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful. | |||

| The Muqawqis responded by sending gifts to Muhammad, including two female slaves, ] and Sirin. Maria became the ] of ],<ref>Buhl. Māriya; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> with some sources reporting that she was later ]. The Muqawqis is reported in Islamic tradition as having presided over the contents of the ] and storing it in an ] ], although he did not convert to Islam.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 416</ref> | |||

| From Muhammad slave of Allah and His Messenger to Muqawqas, vicegerent of Egypt. | |||

| ===Letter to Khosrau II of the Sassanid Kingdom=== | |||

| Peace be upon him who follows true guidance. Thereafter, I invite you to accept Islam. Therefore, if you want security, accept Islam. If you accept Islam, Allah, the Sublime, shall reward you doubly. But if you refuse to do so, you will bear the burden of the transgression of all the Copts. | |||

| ] (original copy)]] | |||

| The letter to ] ({{langx|ar|كِسْرٰى|Kisrá}}) is translated by Muslim historians as: | |||

| {{Blockquote|In the name of God, the Gracious One, the Merciful<br/>From Muhammad, Apostle of God to Khosrow, premier of Persia:<br/>Peace unto whoever follows the guided path, and believes in God and His apostle, and bears witness that there is no god but the one God with no partner to Him and that Muhammad is His servant and His apostle!<br/>And I call you to the call of God, in fact I am the apostle of God to mankind in its entirety, "To warn whoever is alive”.{{cite quran|36|70}}<br/>So submit (i.e., embrace Islam) and be safe . But if you refuse, then verily will the guilt of the ] ("Magians") be upon you.<br/>Seal: Muhammad, Apostle of God}} | |||

| ''"Say (O Muhammad): 'O people of the scripture! Come to a word common to you and us that we worship none but Allah and that we associate nothing in worship with Him, and that none of us shall take others as Lords beside Allah.' Then, if they turn away, say: 'Bear witness that we are Muslims' (those who have surrendered to Allah)." (3:64)'' <ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 415</ref>}} | |||

| According to Muslim tradition, the letter was sent through ]{{efn | name=guillaume | "The apostle sent letters with his companions and sent them to the kings inviting them to Islam. He sent Diḥya b. Khalīfa al-Kalbī to Caesar, king of Rūm; ʿAbdullah b. Ḥudhāfa to Chosroes, king of Persia; ʿAmr b. Umayya al-Ḍamrī to the Negus, king of Abyssinia; Ḥāṭib b. Abū Baltaʾa to the Muqauqis, king of Alexandria;...al-ʿAlā' b. al-Ḥaḍramī to al-Mundhir b. Sāwā al-ʿAbdī, king of Baḥrayn; Shujāʿ b. Wahb al-Asdī to al-Ḥārith b. Abū Shimr al-Ghassānī, king of the Roman border." ], A. ''The Life of Muhammad.''<ref name=sirat2/> p. 789}}<ref name="al-islam.org" /> who, through the governor of ], delivered it to the Khosrau.<ref name="m417">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 417</ref> Upon reading it Khosrow II reportedly tore up the document,<ref>''Kisra'', M. Morony, ''The Encyclopaedia of Islam'', Vol. V, ed. C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, B. Lewis and C. Pellat, (E.J.Brill, 1980), 185.</ref> saying, "A pitiful slave among my subjects dares to write his name before mine"<ref name="moon" /> and commanded ], his vassal ruler of ], to dispatch two valiant men to identify, seize and bring this man from ] (Muhammad) to him. When Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi told Muhammad how Khosrow had torn his letter to pieces, Muhammad is said to have stated, "May God ]," while reacting to the Caesar's behavior saying, "May God preserve his kingdom."<ref>{{cite book |last1=al-ʿAsqalānī |first1=Ibn Ḥajar |author-link= Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani |title=Fatḥ al-Bārī |date=1428 |location=Cairo}}</ref><ref name="al-islam.org" /> | |||

| The Muqawqas responded by sending gifts to Muhammad, including two female slaves, ] and Sirin. Maria became the concubine of Muhammad,<ref>Buhl. Māriya; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> with some sources reporting that she was later freed and married. The Muqawqas is reported in Islamic tradition as having presided over the contents of the parchment and storing it in an ivory casket, although he did not convert to Islam.<ref>al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 416</ref> | |||

| ===Letter to Chosroes=== | |||

| The letter written by Muhammad addressing the Chosroes of Persia was carried by 'Abdullah bin Hudhafa as-Sahmi who, through the governor of Bahrain, delivered it to the Chosroes.<ref name="m417">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) p. 417</ref> The account as transmitted by Muslim historians reads: | |||

| This letter was mentioned in Sahih Muslim.<ref>https://sunnah.com/muslim:2092e {{bare URL inline|date=February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|In the name of Allah, the beneficient, the Merciful. | |||

| ===Other letters=== | |||

| From Muhammad, the Messenger of God, to Kisra, the great King of Persia. | |||

| Peace be upon him who follows the guidance, believes in Allah and His Prophet, bears witness that there is no God but Allah and that I am the Prophet of Allah for the entire humanity so that every man alive is warned of the awe of God. Embrace Islam that you may find peace; otherwise on you shall rest the sin of the Magis.<ref>at-Tabari, at-Tareekh, Vol. III p. 90</ref>}} | |||

| ==== The Sassanid governors of Bahrain and Yamamah ==== | |||

| On receival, the Chosroes reportedly tore up the letter in outrage.<ref>Morony. Kisrā; Encyclopaedia of Islam</ref> This reaction of enmity contrasts with the responses of the other leaders, and was supposedly due to Muhammad having placed his own name before that of the Chosroes.<ref name="m417"/> | |||

| ] (reproduction of a manuscript copy)]] | |||

| ] to Al-Mundhir bin Sawa reserved in ]. Above is the original manuscript, below are modern printing characters for writing the same manuscript.]] | |||

| Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence. ], the governor of ], was apparently an addressee, with a letter having been delivered to him through ]. He reportedly accepted Islam along with some of his subjects, but some of them did not.<ref name="m4">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 421–424</ref> A similar letter was sent to ], the governor of ], who replied that he would only convert if he were given a position of authority within Muhammad's government, a proposition which Muhammad was unwilling to accept.<ref name="m4" /> | |||

| === |

==== The Ghassanids ==== | ||

| Muhammad sent a letter to ], who ruled ] (called by Arabs ''ash-Shām'' "north country, the Levant" in contrast to ''al-Yaman'' "south country, ]") based in Bosra,{{efn | He is referred to as {{lang|ar|عَظِيمِ بُصْرَى}} "premier of Bosra"<ref name=mishkat/><ref name=bukhari/>}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Reda |first1=Mohammed |title=MOHAMMED (S) THE MESSENGER OF ALLAH: محمد رسول الله (ص) |date=1 January 2013 |publisher=Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية |location=Beirut, Lebanon |isbn=978-2-7451-8113-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3R5LDwAAQBAJ |access-date=14 August 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="al-islam.org"/> alternatively ].<ref name=moon/><ref name=halabi>{{cite book |last1=al-Hạlabī |first1=ʻAlī ibn Ibrāhīm Nūr al-Dīn |title=Insān al-ʻuyūn: fī sīrat al-Amīn al-Maʼmūn (Vol.3) |date=1964 |publisher=Musṭạfā al-Bābī al-Hạlabī |pages=300–306 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cdBVAAAAYAAJ |language=ar}}</ref> He hailed from the Ghassanian dynasty of ] Arabs (comparable though superior in status to the ] of ]).{{citation needed|date=July 2022}} The letter reads as follows: | |||

| Apart from the aforementioned personalities, there are other reported instances of correspondence. Mundhir bin Sawa, the governor of ] was apparently an addressee, with a letter having been delivered to him through `Al-`Ala bin al-Hadrami. Some subjects of the governor reportedly converted to Islam, whereas others did not.<ref name="m4">al-Mubarakpuri (2002) pp. 421—424</ref> A similar letter was sent to Hauda bin Ali, the governor of Yamamah, who replied that he would only convert if he were given a position of authority within Muhammad's government, a proposition which Muhammad was unwilling to accept.<ref name="m4"/> The current ruler of ], Harith ibn Abi Shamir ], reportedly reacted less than favourably to Muhammad's correspondence, viewing it as an insult.<ref name="m4"/> Jaifer and `Abd al-Jalani, two brothers belonging to the ruling ] tribe in ], converted to Islam in ] on receiving the letter sent from Muhammad through Amr ibn al-Aas.<ref>Rogerson (2003) p. 202</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|In the name of God, the Gracious One, the Merciful<br/>From Muhammad, Apostle of God to al-Ḥāriṯ the son of ʾAbū Šamir:<br/>Peace unto whoever follows the guided path and believe in God and is sincere !<br/>Thereby I call you to that you believe in the one God with no partner to Him your kingship remains yours.<br/>Seal: Muhammad, Apostle of God}} | |||

| Al-Ghassani reportedly reacted less than favourably to Muhammad's correspondence, viewing it as an insult.<ref name="m4" /> | |||

| ==== The 'Azd ==== | |||

| Jayfar and 'Abd, princes of the powerful ruling '] tribe which ruled ] in collaboration with Persian governance, were sons of the ] Juland (frequently spelt Al Julandā based on the ] pronunciation).<ref>Wilkinson, Arab-persian Land relationships p. 40</ref> They embraced Islam peacefully on 628 AD upon receiving the letter sent from Muhammad through ].<ref>Rogerson (2003) p. 202</ref> The 'Azd subsequently played a major role in the ensuant Islamic conquests. They were one of the five tribal contingents that settled in the newly founded garrison city of ] at the head of the ]; under their general ]; they also took part in the conquest of ] and ].<ref>A. Abu Ezzah, The political situation in Eastern Arabia at the Advent of Islam" p. 55</ref> | |||

| The letter reads as follows: | |||

| {{blockquote|In the name of God, the Gracious One, the Merciful<br/>From Muhammad, Apostle of God to Jayfar and ʿAbd ,<ref name="oman"> The Letter of the Prophet Mohammad to the People of Oman - Advisor to HM the Sultan for Cultural Affairs</ref> the sons of al-Julandī:<br/>Then peace unto whoever follows the guided path!<br/>Thereafter, verily I call you two to the call of Submission ("Islam"). Submit (i.e., embrace Islam) and be safe I, in fact, am the apostle of God to mankind in its entirety, "that he may warn whoever is alive Then indeed you two: if you consent unto Submission to Allah, I shall patronize you. But if you refuse, then indeed your reign is fleeting, and my horsemen shall invade into your courtyard, and my prophethood shall become dominate your kingdom.<br/>Seal: Muhammad, Apostle of God}}{{citation needed|date=July 2022}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| <references /></div> | |||

| ==Citations== | |||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| * {{cite journal| last=El-Cheikh| first=Nadia Maria| title=Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy| journal=Studia Islamica| volume=89| year=1999| issue=89| pages=5–21| doi=10.2307/1596083| jstor=1596083}} | |||

| * {{cite book| author=Forward, Martin| author-link=Martin Forward| year=1998| title=Muhammad: A Short Biography| location=Oxford| publisher=Oneworld| isbn=1-85168-131-0| url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadshortbio0000forw| url-access=registration}} | |||

| *{{cite journal | last=El-Cheikh | first=Nadia Maria | title=Muhammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy | journal=Studia Islamica | volume=89 | year=1999 | month= | pages=5—21 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |

* {{cite book| author=Haykal, Muhammad Husayn| author-link=Muhammad Husayn Haykal| title=The Life of Muhammad| location=Indianapolis| publisher=American Trust Publications| year=1993| isbn=0-89259-137-4}} | ||

| *{{cite book | author= |

*{{cite book |last=Hayward |first=Joel|author-link=Joel Hayward |year=2021 |title=] |publisher=Claritas Books|isbn=9781905837489}} | ||

| *{{cite book |

* {{cite book| author=Lewis, Bernard| author-link=Bernard Lewis| year=1984| title=The Jews of Islam| location=US| publisher=Princeton University Press| isbn=0-691-05419-3}} | ||

| * al-Mubarakpuri |

* {{cite book |author-link=Safiur Rahman al-Mubarakpuri |last=al-Mubarakpuri |first=Saif-ur-Rahman |year=2002 |title=al-Raheeq al-Makhtoom |trans-title=Sealed Nectar |series=] |place=Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |publisher=Dar-Us-Salam Publications |isbn=978-1-59144-071-0 |oclc=228097547}} | ||

| *{{cite book |

* {{cite book| author=Muir, William| author-link=William Muir| title=The Life of Mahomet| location=London| publisher=Smith, Elder & Co.| year=1861| oclc=3265081| url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.217505}} | ||

| *P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, ], E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (Ed.), ''] Online''. Brill Academic Publishers. |

* P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, ], E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (Ed.), ''] Online''. ].{{ISSN|1573-3912}}. | ||

| *{{cite book |

* {{cite book| author=Rogerson, Barnaby| author-link=Barnaby Rogerson| title=The Prophet Muhammad: A Biography| location=UK| publisher=Little, Brown (Time Warner books)| year=2003| isbn=0-316-86175-8}} | ||

| * {{cite book |

* {{cite book| author=Watt, M Montgomery| author-link=William Montgomery Watt| title=Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman| location=United Kingdom| publisher=Oxford University Press| year=1974| isbn=0-19-881078-4| url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadprophets00watt}} | ||

| ===Further reading=== | ===Further reading=== | ||

| * Al-Ismail, Tahia (1998). ''The Life of Muhammad: his life based on the earliest sources''. Ta-Ha publishers Ltd, United Kingdom. {{ISBN|0-907461-64-6}}. | |||

| * {{cite book | author=] | title=Six originaux des lettres du Prophète de l'islam: étude paléographique et historique des lettres | location=Paris | publisher=Tougui | year=1985 | id=ISBN 273630005X}} | |||

| * {{cite book| author=Hamidullah, Muhammad| author-link=Muhammad Hamidullah| title=Six originaux des lettres du Prophète de l'islam: étude paléographique et historique des lettres| location=Paris| publisher=Tougui| year=1985| isbn=2-7363-0005-X}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Watt, M Montgomery | title=Muhammad at Medina | location=United Kingdom | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=1981 | id=ISBN 0195773071}} | |||

| * {{cite book| author=Watt, M Montgomery| title=Muhammad at Medina| location=United Kingdom| publisher=Oxford University Press| year=1981| isbn=0-19-577307-1}} | |||

| * Al-Ismail, Tahia (1998). ''The Life of Muhammad: his life based on the earliest sources''. Ta-Ha publishers Ltd, United Kingdom. ISBN 0907461646. | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170924031703/http://www.pbuh.us/prophetMuhammad.php?f=LT_Monarch |date=2017-09-24 }} | ||

| {{Muhammad footer}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:20, 3 November 2024

Aspect of Muhammad's life| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

| Life |

| Career |

| Miracles |

| Views |

| Perspectives |

| Succession |

| Praise |

| Related |

The diplomatic career of Muhammad (c. 570 – 8 June 632) encompasses Muhammad's leadership over the growing Muslim community (Ummah) in early Arabia and his correspondences with the rulers of other nations in and around Arabia. This period was marked by the change from the customs of the period of Jahiliyyah in pre-Islamic Arabia to an early Islamic system of governance, while also setting the defining principles of Islamic jurisprudence in accordance with Sharia and an Islamic theocracy.

The two primary Arab tribes of Medina, the Aws and the Khazraj, had been battling each other for the control of Medina for more than a century before Muhammad's arrival. With the pledges of al-Aqaba, which took place near Mina, Muhammad was accepted as the common leader of Medina by the Aws and Khazraj and he addressed this by establishing the Constitution of Medina upon his arrival; a document which regulated interactions between the different factions, including the Arabian Jews of Medina, to which the signatories agreed. This was a different role for him, as he was only a religious leader during his time in Mecca. The result was the eventual formation of a united community in Medina, as well as the political supremacy of Muhammad, along with the beginning of a ten-year long diplomatic career.

In the final years before his death, Muhammad established communication with other leaders through letters, envoys, or by visiting them personally, such as at Ta'if; Muhammad intended to spread the message of Islam outside of Arabia. Instances of preserved written correspondence include letters to Heraclius, the Negus and Khosrau II, among other leaders. Although it is likely that Muhammad had initiated contact with other leaders within the Arabian Peninsula, some have questioned whether letters had been sent beyond these boundaries.

The main defining moments of Muhammad's career as a diplomat are the Pledges at al-Aqabah, the Constitution of Medina, and the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah. Muhammad reportedly used a silver seal on letters sent to other notable leaders which he sent as invitations to the religion of Islam.

Early invitations to Islam

Main article: Migration to AbyssiniaMigration to Abyssinia

Muhammad's commencement of public preaching brought him stiff opposition from the leading tribe of Mecca, the Quraysh. Although Muhammad himself was safe from persecution due to protection from his uncle, Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib, a leader of the Banu Hashim, one of the main clans that formed the Quraysh), some of his followers were not in such a position. Several Muslims were mistreated by the Quraysh; some were reportedly beaten, imprisoned, or starved. In 615, Muhammad resolved to send fifteen Muslims to emigrate to the Kingdom of Aksum to receive protection under the Christian ruler called the Najashi in Muslim sources. Emigration was a means through which some of the Muslims could escape the difficulties and persecution faced at the hands of the Quraysh and it also opened up new trading prospects.

Ja'far ibn Abu Talib as Muhammad's ambassador

The Quraysh, on hearing the attempted emigration, dispatched a group led by 'Amr ibn al-'As and Abdullah ibn Abi Rabi'a ibn Mughira in order to pursue the fleeing Muslims. The Muslims reached Axum before they could capture them, and were able to seek the safety of the Negus in Harar. The Qurayshis appealed to the Negus to return the Muslims and they were summoned to an audience with the Negus and his bishops as a representative of Muhammad and the Muslims, Ja`far ibn Abī Tālib acted as the ambassador of the Muslims and spoke of Muhammad's achievements and quoted Qur'anic verses related to Islam and Christianity, including some from Surah Maryam. The Negus, seemingly impressed, consequently allowed the migrants to stay, sending back the emissaries of Quraysh. It is also thought that the Negus may have converted to Islam. The Christian subjects of the Negus were displeased with his actions, accusing him of leaving Christianity, although the Negus managed to appease them in a way which, according to Ibn Ishaq, could be described as favourable towards Islam. Having established friendly relations with the Negus, it became possible for Muhammad to send another group of migrants, such that the number of Muslims living in Abyssinia totalled around one hundred.

Pre-Hijra invitations to Islam

Ta'if

In early June 619, Muhammad set out from Mecca to travel to Ta'if in order to convene with its chieftains, and mainly those of Banu Thaqif (such as 'Abd-Ya-Layl ibn 'Amr). The main dialogue during this visit is thought to have been the invitation by Muhammad for them to accept Islam, while contemporary historian Montgomery Watt observes the plausibility of an additional discussion about wresting the Meccan trade routes that passed through Ta'if from Meccan control. The reason for Muhammad directing his efforts towards Ta'if may have been due to the lack of positive response from the people of Mecca to his message until then.

In rejection of his message, and fearing that there would be reprisals from Mecca for having hosted Muhammad, the groups involved in meeting with Muhammad began to incite townsfolk to pelt him with stones. Having been beset and pursued out of Ta'if, the wounded Muhammad sought refuge in a nearby orchard. Resting under a grape vine, it is here that he invoked God, seeking comfort and protection.

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad on his way back to Mecca was met by the angel Gabriel and the angels of the mountains surrounding Ta'if, and was told by them that if he willed, Ta'if would be crushed between the mountains in revenge for his mistreatment. Muhammad is said to have rejected the proposition, saying that he would pray in the hopes of succeeding generations of Ta'if coming to accept Islamic monotheism.

Pledges at al-'Aqaba

Main article: Second pledge at al-Aqabah

In the summer of 620 during the pilgrimage season, six men of the Khazraj travelling from Medina came into contact with Muhammad. Having been impressed by his message and character, and thinking that he could help bring resolution to the problems being faced in Medina, five of the six men returned to Mecca the following year bringing seven others. Following their conversion to Islam and attested belief in Muhammad as the messenger of God, the twelve men pledged to obey him and to stay away from a number of Islamically sinful acts. This is known as the First Pledge of al-'Aqaba by Islamic historians. Following the pledge, Muhammad decided to dispatch a Muslim ambassador to Medina and he chose Mus'ab ibn 'Umair for the position, in order to teach people about Islam and invite them to the religion.

With the slow but steady conversion of persons from both the Aws and Khazraj present in Medina, 75 Medinan Muslims came as pilgrims to Mecca and secretly convened with Muhammad in June 621, meeting him at night. The group made to Muhammad the Second Pledge of al-'Aqaba, also known as the Pledge of War. The people of Medina agreed to the conditions of the first pledge, with new conditions including included obedience to Muhammad, the enjoinment of good and forbidding evil. They also agreed to help Muhammad in war and asked of him to declare war on the Meccans, but he refused.

Some western academics are noted to have questioned whether or not a second pledge had taken place, although William M. Watt argues that there must have been several meetings between the pilgrims and Muhammad on which the basis of his move to Medina could be agreed upon.