| Revision as of 23:47, 17 December 2019 edit175.203.103.219 (talk) Why it is not the capital of the Diyarbakır Province? Please explain it in the talk page.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:45, 30 December 2024 edit undoUness232 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,291 edits Reverting edit(s) by I have no idea wgat im doing (talk) to rev. 1263992554 by Srich32977: Constantinople was a common name until the 20th century, even in Turkish as Kostantiniyye. (UV 0.1.6)Tags: Ultraviolet Undo | ||

| (702 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|City in Turkey}} | |||

| {{redirect|Amid}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | {{other uses}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox settlement <!--more fields are available for this Infobox--See Template:Infobox Settlement--> | {{Infobox settlement <!--more fields are available for this Infobox--See Template:Infobox Settlement--> | ||

| | settlement_type |

| settlement_type = ] | ||

| | subdivision_type |

| subdivision_type = Country | ||

| | subdivision_name |

| subdivision_name = ] | ||

| | timezone |

| timezone = ] | ||

| | utc_offset |

| utc_offset = +3 | ||

| | map_caption |

| map_caption = Location of Diyarbakır within Turkey | ||

| | official_name |

| official_name = Diyarbakır | ||

| | image_skyline |

| image_skyline = {{multiple image|total_width=270px|perrow=1/2/2/2|border=infobox | ||

| | image1 = Goletli Park, Diyarbakir.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = '''Top left:''' Ali Pasha Mosque, '''Top right:''' Nebi Mosque, '''2nd:''' Seyrangeha Park, '''3rd left:''' Dört Ayaklı Minare Mosque, '''3rd upper right:''' Deriyê Çiyê, '''3rd lower right:''' On Gözlü Bridge (or Silvan Bridge), over Tigris River, '''Bottom left:''' Diyarbakır City Wall, '''Bottom right:''' Gazi Köşkü (Veterans Pavilion) | |||

| | |

| alt1 = | ||

| | |

| image2 = Diyarbakir Great Mosque DSCF8201.jpg | ||

| | |

| alt2 = | ||

| | image3 = Karasanserai Diyarbakir.png | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| | |

| alt3 = | ||

| | |

| image4 = Pira dehderî 2014.JPG | ||

| | |

| alt4 = | ||

| | image5 = Diyarbakr Western City Wall.JPG | |||

| | population_footnotes = <ref name="thekurdishproject.org">{{cite web|title=https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/turkish-kurdistan/diyarbakir/}}</ref> | |||

| | |

| alt5 = | ||

| | |

| image6 = Seyrangeha Parkormanê Amed 2010.JPG | ||

| | |

| alt6 = | ||

| | |

| image7 = Gazi Pavillion.jpg | ||

| | |

| alt7 = | ||

| }} | |||

| | demographics_type1 = Ethnic groups<br /> | |||

| | image_caption = '''Clockwise from top:''' A pond park in Diyarbakir, ], ], Gazi Pavillion, A park in Diyarbakir, ] (The Dicle Bridge), ]. | |||

| | demographics1_footnotes = {{plainlist| | |||

| | imagesize = 250px | |||

| *Turkish | |||

| | blank_emblem_type = Emblem of Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality | |||

| *Kurdish (majority)<ref name="thekurdishproject.org"/> | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| *Assyrian (several thousands) | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| *Armenian (hundreds)}} | |||

| | subdivision_type2 = ] | |||

| | postal_code_type = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name2 = ] | |||

| | postal_code = 21x xx | |||

| | |

| area_total_km2 = 15058 | ||

| | area_urban_km2 = 2410 | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| | |

| area_metro_km2 = 2410 | ||

| | population_as_of = 2021 estimation | |||

| | website = | |||

| | population_footnotes = <ref name="citypopulation.de">{{Cite web|url=https://www.citypopulation.de/en/turkey/admin/|title=Turkey: Administrative Division (Provinces and Districts) – Population Statistics, Charts and Map|website=www.citypopulation.de}}</ref> | |||

| | leader_name = Hasan Basri Güzeloğlu (State Appointed Mayor) | |||

| | population_total = 1,791,373 | |||

| | population_urban = 1,129,218 | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | population_metro = 1,129,218 | |||

| | pushpin_map = Turkey | |||

| | population_density_km2 = auto | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|37.91|40.24|region:TR|display=inline}} | |||

| | population_density_urban_km2 = auto | |||

| | name = | |||

| | population_density_metro_km2 = auto | |||

| | demographics_type2 = GDP | |||

| | demographics2_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web |title=Statistics by Theme > National Accounts > Regional Accounts |url=https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/ilgosterge/?locale=tr |access-date=11 May 2023 |website=www.turkstat.gov.tr}}</ref> | |||

| | demographics2_title1 = ] | |||

| | demographics2_info1 = ] 62.494 billion<br />] 6.959 billion (2021) | |||

| | demographics2_title2 = Per capita | |||

| | demographics2_info2 = ] 34,964<br />] 3,893 (2021) | |||

| | elevation_m = 675 | |||

| | postal_code_type = ] | |||

| | postal_code = 21x xx | |||

| | blank_info = 21 | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| | area_code = 412 | |||

| | website = | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = Ayşe Serra Bucak Küçük | |||

| | leader_party = ] | |||

| | pushpin_map = Turkey #Earth | |||

| | pushpin_relief = 1 | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|37.91|40.24|region:TR|display=inline}} | |||

| | image_blank_emblem = Diyarbakır City logo.png | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Diyarbakır''' ({{IPA|tr|diˈjaɾ.bakɯɾ}}; {{Langx|hy|Տիգրանակերտ|translit=Tigranakert}}, local pronunciation: ''Dikranagerd''; {{Langx|ku-Latn|Amed}}; {{Langx|syr|ܐܡܝܕ|translit=Āmīd}}), formerly '''Diyarbekir''', is the largest ]-majority city in ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Bois|first1=Th|last2=Minorsky|first2=V.|last3=MacKenzie|first3=D. N.|date=2012-04-24|title=Kurds, Kurdistān|url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/kurds-kurdistan-COM_0544?s.num=167&s.start=100|journal=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition|language=en}}</ref> It is the administrative center of ]. | |||

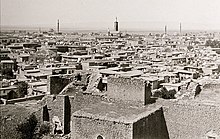

| Situated around a high plateau by the banks of the ] river on which stands the historic ], it is the administrative capital of the ] of southeastern ]. It is the second-largest city in the ]. As of December 2021, the Metropolitan Province population was 1,791,373 of whom 1,129,218 lived in the built-up (or metro) area made of the 4 urban districts (], ], ] and ]). | |||

| '''Diyarbakır''' ({{lang-ku|Amed|script=Latn}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://tirsik.net/danegeh/pirtuk/ismail%20bulbul/anamneza%20bi%20kurmancî.pdf|title=Kürtçe Anamnez, Anamneza bi Kurmancî|last=|first=|date=|editor-last=Avcýkýran|editor-first=Dr. Adem|website=Tirsik|page=55|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=17 December 2019}}</ref>, {{lang-ar|ديار بكر}}, {{lang-arm|Տիգրանակերտ|Tigranakert}}, {{lang-syr|ܐܡܝܕܐ|Amida}})<ref name="Gunter">{{cite book|last1=Gunter|first1=Michael M.|authorlink1=Michael M. Gunter|title=Historical Dictionary of the Kurds|date=2010|publisher=Scarecrow Press|page=. }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=King|first1=Diane E.|title=Kurdistan on the Global Stage: Kinship, Land, and Community in Iraq|date=2013|publisher=Rutgers University Press|page=|quote=Diyarbakir's Kurdish name is “Amed.”}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Akyol|first1=Mustafa|title=Pro-Kurdish DTP sweeps Diyarbakir|url=http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/english/domestic/11318806.asp?scr=1|work=]|date=2007|quote=Amed is the ancient name given to Diyarbakır in the Kurdish language.}}</ref> is one of the largest ] in southeastern ] and the official capital of the ]. It is considered by ] as the unofficial capital of "]".<ref name="Gunter"/><ref name="Jr.2015">{{cite book|author=Joseph R. Rudolph Jr.|title=Encyclopedia of Modern Ethnic Conflicts, 2nd Edition [2 volumes]|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OjkVCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA484|date=7 December 2015|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1-61069-553-4|page=484|quote=As some have noted, Turkey's road to the EU lies through Diyarbakir, the unofficial capital of Turkish Kurdistan.}}</ref><ref name="Hamelink2016">{{cite book|author=Wendelmoet Hamelink|title=The Sung Home. Narrative, Morality, and the Kurdish Nation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kH8JDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA307|date=6 April 2016|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-31482-5|page=307|quote=This is also related to the unique position of Diyarbakır as the unofficial capital city of Turkish Kurdistan, as such ...}}</ref><ref name="AyersQuinn2009">{{cite book|author1=William Ayers|author2=Therese M. Quinn|author3=David Stovall|title=Handbook of Social Justice in Education|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oZaNAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA187|date=2 June 2009|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-59614-9|page=187|quote=The unofficial capital of North Kurdistan (Turkish Kurdistan) is Diyarbakir in Turkish, but Amed in Kurdish.}}</ref><ref name="MassicardWatts2012">{{cite book|author1=Elise Massicard|author2=Nicole Watts|title=Negotiating Political Power in Turkey: Breaking up the Party|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TT4VIY31obEC&pg=PA99|date=12 December 2012|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-13687-1|page=99|quote=This chapter explores these questions through an analysis of pro-Kurdish parties1 and their social footing in the city of Diyarbakır, one of the largest cities in Turkey.}}</ref><ref name="LaberWhitman1988">{{cite book|author1=Jeri Laber|author2=Lois Whitman|title=Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Kurds of Turkey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SECQ3EaQuXgC&pg=PP8|date=1 January 1988|publisher=Human Rights Watch|isbn=978-0-938579-41-0|page=8|quote=It began in Diyarbakir, the unofficial capital of Turkish Kurdistan,}}</ref> Situated on the banks of the ] River, it is the administrative capital of the ]. It is the third-largest city in Turkey's ], after ] and ]. | |||

| Diyarbakır has been a main focal point of the ] between the Turkish state and various ] separatist groups, and is seen by many Kurds as the de facto capital of ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/tensions-increase-already-fragile-kurdish-peace-process-faulters-turkey|title=Tensions increase as already fragile Kurdish peace process faulters in Turkey|website=Middle East Eye}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/24/world/europe/an-aleppo-like-landscape-in-a-kurdish-redoubt-of-turkey.html|title=An Aleppo-like Landscape in a Kurdish Redoubt of Turkey|newspaper=The New York Times|date=24 December 2016|last1=Nordland|first1=Rod}}</ref> The city was intended to become the capital of an ] following the ], but this was disregarded following subsequent political developments.<ref>{{cite web|last=Kubilay|first=Arin|date=2015-03-26|title=Turkey and the Kurds – From War to Reconciliation?|url=https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3229m63b|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Köksal|first=Yonca|date=2005|title=Hakan Özoğlu. Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries |journal=New Perspectives on Turkey|volume=32|pages=227–230|doi=10.1017/s0896634600004180|s2cid=148060175|issn=0896-6346}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Şerif Paşa |title=Memorandum on the claims of the Kurd people |oclc=42520854}}</ref> | |||

| It has been a focal point of the ] between the Turkish state and various ] insurgent groups. | |||

| On 6 February 2023 Diyarbakır was affected by the twin ], which inflicted some damage on its city walls.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Earthquakes batter Turkey, Syria's historical monuments |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/2/7/earthquakes-damage-turkey-syrias-historic-mosques-and-castles |access-date=2023-02-14 |website=www.aljazeera.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| =={{anchor|Names and etymology}}Names and etymology== | |||

| {{see also|Names of Diyarbakır in different languages}} | |||

| The name Diyarbakır ({{lang-ar|دیار بکر}}, {{transl|ar|''Diyaru Bakr''}}, which means the ''Land of Bakir''; {{lang-hy|Տիգրանակերտ}}, {{transl|hy|'']''}};<ref>] pronunciation: ''Dikranagerd''; {{cite book|last=Hovannisian|first=Richard G.|title=Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa|year=2006|publisher=Mazda Publishers|location=Costa Mesa, California|isbn=9781568591537|page=2|authorlink=Richard G. Hovannisian|quote=The city that later generations of Armenians would call Dikranagerd was actually ancient Amid or Amida (now Diyarbekir or Diyarbakır), a great walled city with seventy-two towers...}}</ref> {{lang-grc|Άμιδα}}, {{transl|grc|'']''}}; {{lang-ota|دیاربکر}}, {{transl|ota|''Diyâr-ı Bekr''}}; {{lang-syr|ܐܡܝܕ}}) is inscribed as Amed on the sheath of a sword from the ]n period, and the same name was used in other contemporary Syriac and Arabic works.<ref name="airlines"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111223164814/http://www.turkishairlines.com/fi-FI/skylife/2005/november/articles/diyarbakir.aspx |date=23 December 2011 }}. Turkish Airlines. Retrieved on 2012-05-13.</ref> The Romans and Byzantines called the city '']''.<ref name="airlines"/> Another medieval use of the term as ''Amit'' is found in ] official documents in 1358.<ref>Zehiroglu, Ahmet M. ; "Trabzon Imparatorlugu" 2016 ({{ISBN|978-605-4567-52-2}}) ; p.223</ref> Among the ] and ] it was known as "Black Amid" (''Kara Amid'') for the dark color of its walls, while in the ''Zafername'', or eulogies in praise of military victories, it is called "Black Fortress" (''Kara Kale'').<ref name="airlines"/> In the ] and some other Turkish works it appears as ''Kara Hamid''.<ref name="airlines"/> | |||

| == Names and etymology == | |||

| Following the ]s in the seventh century, the Arab ] settled in this region,<ref name="airlines"/> which became known as the '']'' ("]s of the Bakr tribe", in {{lang-ar|ديار بكر}}, {{transl|ar|''Diyar Bakr''}}).<ref>Abdul- Rahman Mizouri . College of Arts/ Dohuk University (2001)</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Verity Campbell|title=Turkey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jstw7Sxkp4gC&pg=PA621|accessdate=13 May 2012|date=1 April 2007|publisher=Lonely Planet|isbn=978-1-74104-556-7|pages=621–}}</ref> In 1937, ] visited Diyarbakir and, after expressing uncertainty on the exact etymology of the city, ordered that it be renamed "Diyarbakır", which means "land of copper" in Turkish after the abundant resources of ] around the city.<ref>See ] (2011), ''The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 244. {{ISBN|0-19-960360-X}}.</ref> | |||

| In ancient times the city was known as ], a name which could derive from an older Assyrian toponym ''Amedi''.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Comfort |first1=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FnwvEAAAQBAJ&dq=amida+diyarbakir&pg=PA123 |title=How did the Persian King of Kings Get His Wine? The upper Tigris in antiquity (c. 700 BCE to 636 CE) |last2=Marciak |first2=Michał |publisher=Archaeopress Publishing Ltd |year=2018 |isbn=978-1-78491-957-3 |pages=123–124 |language=en}}</ref> The name ''Āmid'' was also used in ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sinclair |first=T. A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Na1EBAAAQBAJ&q=Arabic+%22Amid%22&pg=PA163 |title=Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III |publisher=Pindar Press |year=1989 |isbn=978-0-907132-34-9 |page=161 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":7" /> The name ''Amit'' is found in official documents of the ] from 1358.<ref>Zehiroglu, Ahmet M. ; "Trabzon Imparatorlugu" 2016 ({{ISBN|978-605-4567-52-2}}) ; p. 223</ref> | |||

| After the ] of the 7th century, the city became known as ''Diyar Bakr'' ({{langx|ar|ديار بكر|translit=Diyār Bakr|lit=the abode of Bakr|links=no}}), in reference to the territory of the ] tribe, the '']''.<ref name=":7" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Suwaed |first=Muhammad |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P8yhCgAAQBAJ&dq=diyarbakir+banu+bakr&pg=PA45 |title=Historical Dictionary of the Bedouins |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=2015 |isbn=978-1-4422-5451-0 |page=45 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":24">{{Cite book |last= |first= |title=The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-530991-1 |editor-last=M. Bloom |editor-first=Jonathan |volume=2 |location= |pages= |language=en |chapter=Diyarbakır |editor-last2=S. Blair |editor-first2=Sheila}}</ref> That tribe had already settled in ] during the pre-Islamic period. In the 7th century, during the caliphate of ] and under the regional governorship of ], a portion of the tribe was ordered to settle further north in the lands near the city.<ref name=":7">{{Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition|volume=2|article=Diyār Bakr|last1=Canard|first1=M.|first2=Cl.|last2=Cahen|first3=Mükrimin H.|last3=Yinanç|last4=Sourdel-Thomine|first4=J.|pages=343–347}}</ref> The city was later also known in ] as Kara-Amid ("Black Amid"), on account of its black basalt walls.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lipiński |first=Edward |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rrMKKtiBBI4C&dq=kara+amid+black+amid+diyarbakir&pg=PA136 |title=The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion |date=2000 |publisher=Peeters Publishers |isbn=978-90-429-0859-8 |page=136 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ]. The western half is currently (2017) being demolished.]] | |||

| The earliest reference to the city comes from Assyrian records which identify it as being the capital of the ] kingdom of ] (c. 1300 BC). In the ninth century BC, the city joined a rebellion against the Assyrian king ]. The city was later reduced to being a province of the ]. | |||

| In November 1937, Turkish President ] visited the city and after expressing uncertainty on the exact etymology of the city's name, "Diyarbekir", in December of the same year ordered that it be renamed "Diyarbakır", which means "land of copper" in Turkish after the abundant resources of ] around the city.<ref>See ] (2011), ''The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 244. {{ISBN|0-19-960360-X}}.</ref> This was one of the early examples of the ] process of non-Turkish place names, in which non-Turkish (Kurdish, Armenian, Arabic and other) geographical names were changed to Turkish alternatives.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nişanyan|first=Sevan|title=Adını unutan ülke: Türkiye'de adı değiştirilen yerler sözlüğü|date=2010|publisher=Everest Yayınları|isbn=978-975-289-730-4|edition=1. basım|location=İstanbul|oclc=670108399}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Social relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915|date=2012 |editor=Joost Jongerden |editor2=Jelle Verheij|isbn=978-90-04-23227-3|location=Leiden |publisher=Brill |oclc=808419956}}</ref> | |||

| From 189 BCE to 387 CE, the region to the east and south of present Diyarbakır came under the rule of Greater Armenia and was part of ] province (ashkhar). | |||

| The ] name of the city is ''Tigranakert/Dikranagerd'' ({{Lang|hy|Տիգրանակերտ}}).<ref name="Armenian Tigranakert">] pronunciation: ''Dikranagerd''; {{cite book |last=Hovannisian |first=Richard G. |title=Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa |publisher=Mazda Publishers |year=2006 |isbn=978-1-56859-153-7 |location=Costa Mesa, California |page=2 |quote=The city that later generations of Armenians would call Dikranagerd was actually ancient Amid or Amida (now Diyarbekir or Diyarbakır), a great walled city with seventy-two towers... |author-link=Richard G. Hovannisian}}</ref> It is known as {{Lang|ku-Latn|Amed}} in ]<ref>{{cite book |author1=Adem Avcıkıran |url= |title=Kürtçe Anamnez Anamneza bi Kurmancî |date=2009 |page=55 |language=tr, ku }}</ref> and in ] as {{Lang|sc|ܐܡܝܕ}} (Āmīd).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Smith |first=J. Payne |title=ܐܡܝܕ |url=https://sedra.bethmardutho.org/lexeme/get/16400 |publisher=Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1903}}</ref> | |||

| Later, the Romans colonized the city and named it ], after the earlier name ]. During the Roman rule, the first city walls were constructed in 297. Later, the greater walls were built as per the command of the Roman emperor ]. The Romans were succeeded by the Muslim Arabs. It was the leader of the Arab Bekr tribe, Bekr Bin Vail, who named the city Diyar Bakr, meaning "the country of Bakr", i.e. Arabs. | |||

| == History == | |||

| After a few centuries, Diyarbakır came under the ] and earned the status of the capital of ]. The city became the base of army troops who guarded the region against Persian invasion. Diyarbakır faced turbulence in the 20th century, particularly with the onset of ]. The majority of the city's Assyrian and Armenian population were massacred and deported during the ] & ] in 1915. In 1925, armed Kurdish groups rose in the ] against the newly established secular government of the ] with the aim to revive the Islamic ] and sultanate, but were defeated by Turkish forces. | |||

| {{Main|History of Diyarbakır}} | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | === Antiquity === | ||

| ] of ] in the ], 9th century BC]] | |||

| People have inhabited the area around Diyarbakır since the Stone Age. The first major civilization to establish itself in the region of Diyarbakır was the ] kingdom of the ]. It was then ruled by a succession of nearly every polity that controlled ], including the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>], ''The Kingdom of the Hittites'', 1999 p. 137</ref> The ] gained control of the city in 66 BC, by which stage it was named "Amida".<ref>. Italian.classic-literature.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-13.</ref> In 359, ] ] after a siege of 73 days.<ref name="Command, Kimberly Kagan p23">''The Eye of Command'', ], p. 23</ref><ref name=":10">{{Cite book |title=Ahmady, Kameel 2009: ]. GABB Publication, Diyarbakır. p. 200. |editor-link=Kameel Ahmady |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| According to the '']'' of ], as Amida, Diyarbakır was the major city of the ] of ].<ref name=":1">{{cite web|last=Nicholson|first=Oliver|title=Mesopotamia, Roman|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-3135|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|edition=online|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-11-28}}</ref> It was the ] of the Christian ] of Mesopotamia.<ref name=":1" /> Ancient texts record that ancient Amida had an ], '']'' (public baths), warehouses, a ] monument, and ] supplying and distributing water.<ref name=":2">{{cite web|last=Keser-Kayaalp|first=Elif|title=Amida|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-207|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|edition=online|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-11-28}}</ref> The Roman historian ] was serving in the ] during the ] by the ] under ] ({{Reign|309|379}}), and described the successful siege in detail.<ref name=":2" /> Amida was then enlarged by refugees from ancient Nisibis (]), which the emperor ] ({{Reign|363|364}}) was forced to evacuate and cede to Shapur's Persians after the defeat of his predecessor ], becoming the main Roman stronghold in the region.<ref name=":2" /> The ] attributed to ] describes the capture of Amida by the Persians under ] ({{Reign|488|531}}) in the second ] in 502–503, part of the ].<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| The area around Diyarbakır has been inhabited by humans from the stone age with tools from that period having been discovered in the nearby Hilar cave complex. The pre-pottery neolithic B settlement of Çayönü dates to over 10,000 years ago and its excavated remains are on display at the ]. Another important site is Girikihaciyan Tumulus in ].<ref>Charles Gates, , 2011, </ref> | |||

| Either the emperor ] ({{Reign|491|518}}) or the emperor ] ({{Reign|527|565}}) rebuilt the walls of Amida, a feat of defensive architecture praised by the Greek historian ].<ref name=":2" /> As recorded by the works of ], ], and Procopius, the Romans and Persians continued to contest the area, and in the ] Amida was captured and held by the Persians for twenty-six years, being recovered in 628 for the Romans by the emperor ] ({{Reign|610|641}}), who also founded a church in the city on his return to ] (]) from Persia the following year.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /> | |||

| The first major civilization to establish themselves in the region of what is now Diyarbakır were the ] kingdom of the ]. The city was first mentioned by Assyrian texts as the capital of a Semitic kingdom. It was then ruled by a succession of nearly every polity that controlled Upper Mesopotamia, including the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>], ''The Kingdom of the Hittites'', 1999 p. 137</ref> The ] gained control of the city in 66 BC, by which stage it was named "Amida".<ref>. Italian.classic-literature.co.uk. Retrieved on 2012-05-13.</ref> In 359, ] ] after a siege of 73 days which is vividly described by the Roman historian ].<ref name="Command, Kimberly Kagan p23">''The Eye of Command'', ], p. 23</ref> | |||

| === Ecclesiastical history === | === Ecclesiastical history === | ||

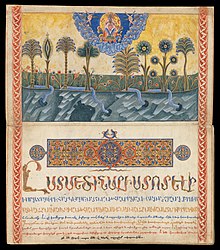

| ] created in Diyarbakır in 1601 by the Serapion of Edessa for the future ], now at the ]]] | |||

| ] took hold in the region between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, particularly amongst the Assyrians of the city. The earliest documented bishop of Amida was Simeon of the ], who took part in the ] in 325, on behalf of the Assyrians. Maras was at the ] in 381. In the next century, Saint ] (who died in 425, and is included in the ]<ref>''Martyrologium Romanum'' (Vatican Press 2001 {{ISBN|978-88-209-7210-3}}), under 9 April</ref>) was noted for having sold the church's gold and silver vessels to ransom and assist Persian prisoners of war. | |||

| ] took hold in the region between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, particularly amongst the ] of the city. The ] ] (408–450) divided the ] of ] into two, and made Amida the capital of Mesopotamia Prima, and thereby also the ] for all the province's ]s.<ref name="edwards">{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Edwards|first1=Robert W. |entry=Diyarbakır |encyclopedia=The Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology |editor=Paul Corby Finney |date=2016 |publisher=William B. Eerdmans |location=Grand Rapids, Michigan |isbn=978-0-8028-9016-0| page=115}}</ref> | |||

| At some stage, Amida became a see of the ]. The bishops who held the see in 1650 and 1681 were in ] with the ], and in 1727 Peter Derboghossian sent his profession of faith to Rome. He was succeeded by two more bishops of the ], Eugenius and Ioannes of ], the latter of whom died in ] in 1785. After a long vacancy, three more bishops followed.<ref name="Gams1" /><ref name="Gams2" /><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=Arango |first=Tim |date=2015-04-23 |title=Hidden Armenians of Turkey Seek to Reclaim Their Erased Identities |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/24/world/europe/armenians-turkey.html |access-date=2023-10-06 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><!-- Not all of these citations may be relevant for the preceding content, but they've been repeated here to clarify that the entire paragraph was originally attributed to these four sources, prior to new content and a new source being added in the middle. --> The diocese had some 5,000 Armenian Catholics in 1903,<ref>, 1903, p. 173.</ref> but it lost most of its population in the 1915 ]. The last ] of the see, Andreas Elias Celebian, was killed with some 600 of his flock in the summer of 1915.<ref name=Gams1>Pius Bonifacius Gams, , Leipzig 1931, p. 456</ref><ref name=Gams2>Pius Bonifacius Gams, , Complementi, Leipzig 1931, p. 93</ref><ref name=":8">F. Tournebize, v. ''Amid ou Amida'', in , vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 1246–1247</ref><ref name=":9">Hovhannes J. Tcholakian, ''L'église arménienne catholique en Turquie'', 1998</ref> | |||

| ] ] (408–450) divided the ] of ] into two, and made Amida the capital of Mesopotamia Prima, and thereby also the ] for all the province's ]s.<ref name="edwards">{{cite book|last1=Edwards|first1=Robert W., "Diyarbakır" |title=The Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology, ed., Paul Corby Finney |date=2016 |publisher=William B. Eerdmans Publishing| location=Grand Rapids, Michigan |isbn=978-0-8028-9016-0| pages=115}}</ref> A 6th-century '']'' indicates as ]s of Amida the sees of ], ], ], ], ], Kitharis, ], and ].<ref>, pp. 96 and 145.</ref> The '']'' adds ] and ]. | |||

| An eparchy for the local members of the ] was established in 1862. ] during the First World War brought an end to the existence of both these Syrian residential sees.<ref name="Gams1" /><ref name="Gams2" /><ref>S. Vailhé, ''Antioche. Patriarcat syrien-catholique'', in Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, Vol. I, Paris 1903, coll. 1433</ref><ref>O. Werner, , Freiburg 1890, p. 164</ref> | |||

| The names of several of the successors of Acacius are known, but their orthodoxy is unclear. The last whose orthodoxy is certain is Cyriacus, a participant in the ] (553). Many bishops of the Byzantine Empire fled in the face of the Persian invasion of the early 7th century, with a resultant spread of the ], ] gives a list of Jacobite bishops of Amida down to the 13th century.<ref>Michel Lequien, , Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 989–996</ref> | |||

| ] photographed after the restoration, 2012. On 26 March 2016 the Turkish government confiscated St. Giragos, under Article 27 of the Expropriation Law.<ref>http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/04/turkey-pkk-clashes-armenian-church-collateral-damage.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160414010824/http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/04/turkey-pkk-clashes-armenian-church-collateral-damage.html |date=14 April 2016 }} Why the Turkish government seized this Armenian church</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/24/world/europe/turkeys-seizure-of-churches-and-land-alarms-armenians.html|title=Turkey’s Seizure of Churches and Land Alarms Armenians|first=Ceylan|last=Yeginsu|date=23 April 2016|publisher=|via=NYTimes.com}}</ref>]] | |||

| At some stage, Amida became a see of the Armenian Christians. The bishops who held the see in 1650 and 1681 were in communion with the Holy See, and in 1727 Peter Derboghossian sent his profession of faith to Rome. He was succeeded by two more Catholic Armenians, Eugenius and Ioannes of Smyrna, the latter of whom died in ] in 1785. After a long vacancy, three more bishops followed. The diocese had some 5,000 Armenian Catholics in 1903,<ref>, 1903, p. 173.</ref> but it lost most of its population in the ]. The last ] of the see, Andreas Elias Celebian, was killed with some 600 of his faithful in the summer of 1915.<ref name=Gams1>Pius Bonifacius Gams, , Leipzig 1931, p. 456</ref><ref name=Gams2>Pius Bonifacius Gams, , Complementi, Leipzig 1931, p. 93</ref><ref>F. Tournebize, v. ''Amid ou Amida'', in , vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 1246–1247</ref><ref>Hovhannes J. Tcholakian, ''L'église arménienne catholique en Turquie'', 1998</ref> | |||

| === Middle Ages === | |||

| An eparchy for the local members of the ] was established in 1862. ], who was its first bishop, was elected patriarch in 1866, he kept the governance of the see of Amida, which he exercised through a patriarchal vicar. The eparchy was united to that of ] in 1888. Persecution in Turkey during the First World War brought an end to the existence of both these Syrian residential sees.<ref name="Gams1"/><ref name="Gams2"/><ref>S. Vailhé, ''Antioche. Patriarcat syrien-catholique'', in Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, Vol. I, Paris 1903, coll. 1433</ref><ref>O. Werner, , Freiburg 1890, p. 164</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Diyar Bakr}} | |||

| ] | |||

| However, in 1966 a ] with jurisdiction over all Chaldean Catholic Turks was revived in Diyarbakır, with the city being as episcopal see and location of the diocesan ]. | |||

| In 639, as part of the ] during the early ], Amida fell to the armies of the ] led by ], and the Great Mosque of Amida was constructed afterwards in the city's centre, possibly on the site of the Heraclian Church of Saint Thomas.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":10" /> There were as many as five Christian ] in the city, including the ] and several ancient churches mentioned by John of Ephesus.<ref name=":2" /> One of these, the ], remains the city's ] and the see of the ] in the ].<ref name=":2" /> Another ancient church, the Church of Mar Cosmas, was seen by the British explorer ] in 1911 but was destroyed in 1930, while the former ], in the walled citadel, may originally have been built for Muslim use or for the ].<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| The city was part of the ] and then the ], but then came under more local rule until its recovery in 899 by forces loyal to the caliph ] ({{Reign|892|902}}) before falling under the sway of first the ] and then the ], followed by a period of control by the ]. The city was taken by the ] in 1085 and by the ] in 1183. Ayyubid control lasted until the ], with its last Ayyubid ruler ]. The Mongols of ] captured of the city in 1260 (]), following a long siege with a small Mongol force and a much larger Georgian and Armenian force under the Georgian leader ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sicker |first1=Martin |title=The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna |date=2000 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing USA |isbn=978-0-313-00111-6 |page=111 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b6vOEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA111 |language=en}}</ref> Between the Mongol occupation and conquest by the ] of Iran, the ] and ] – two ] confederations – were in control of the city in succession. Diyarbakır was conquered by the ] in 1514 by ], in the reign of the sultan ] ({{Reign|1512|1520}}). ], the Safavid governor of Diyarbakir, was evicted from the city and killed in the following ] in 1514.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-08-16 |title=Battle of Chaldiran {{!}} Summary {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Chaldiran |access-date=2023-10-06 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| As of 2015, there are two Chaldean Churches, and three Armenian churches in at least periodic operation. Three other churches are in ruins, all Armenian: one outside Sur district, one in it, and one in the citadel that is now part of a museum complex. | |||

| === Safavids and Ottomans === | |||

| {{See also|Diyarbekir Eyalet|Diyarbekir Vilayet}} | |||

| No longer a residential bishopric until 1966 (Chaldean rite), Amida is today listed by the ] as a multiple ],<ref>''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 {{ISBN|978-88-209-9070-1}}), p. 831</ref> separately for the Latin Roman Rite and two ] particular churches ''sui iuris''. | |||

| ]|left]] | |||

| The ] saw it expand into ] and all but the eastern regions of ] at the expense of the Safavids. From the early 16th century, the city and the wider region was the source of intrigue between the Safavids and the ], both of whom sought the support of the Kurdish chieftains around ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Özoğlu|first=Hakan|title=Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries|date=2004|publisher=SUNY Press|isbn=978-0-7914-5993-5|pages=47–49|language=en}}</ref> It was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1514 in the campaigns of ], under the rule of Sultan ]. ], the Safavid Governor of Diyarbakir, was evicted from the city and killed in the following ] in 1514.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Following their victory, the Ottomans established the ] with its administrative centre in Diyarbakır. The Eyalet of Diyarbakır corresponded to today's ], a rectangular area between the ] to ] and from the southern shores of ] to ] and the beginnings of the ], although its borders saw some changes over time. The city was an important military base for controlling the region and at the same time a thriving city noted for its craftsmen, producing glass and metalwork. For example, the doors of ]'s tomb in ] were made in Diyarbakır, as were the gold and silver decorated doors of the tomb of ] in ]. Ottoman rule was confirmed by the 1555 ] which followed the ]. | |||

| ===== Latin titular see ===== | |||

| '''Amida of the Romans''' was suppressed in 1970, having had many archiepiscopal incumbents with a singular episcopal exception : | |||

| * ] (19 December 1725 – 8 March 1728) | |||

| * Francisco Casto Royo (15 December 1783 – September 1803) | |||

| * Gaétan Giunta (6 October 1829 – unknown date) | |||

| * ''Titular Bishop Augustus van Heule, ] (S.J.) (9 September 1864 – 9 June 1865) | |||

| * Colin Francis McKinnon (30 August 1877 – 26 September 1879) | |||

| * Francis Xavier Norbert Blanchet (26 January 1881 – 18 June 1883) | |||

| * ] (21 March 1884 – 11 January 1894) (later Cardinal) | |||

| * Francesco Sogaro, ] (F.S.C.I.) (18 August 1894 – 6 February 1912) | |||

| * James Duhig (27 February 1912 – 13 January 1917) | |||

| * John Baptist Pitaval (29 July 1918 – 23 May 1928) | |||

| * ] (12 October 1928 – 15 December 1958) (later Cardinal) | |||

| *] (8 August 1959 – 10 May 1963) | |||

| *] (23 May 1963 – 17 March 1969) | |||

| * Joseph Cheikho (7 March 1970 – 22 August 1970) | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ===== Armenian Catholic titular see ===== | |||

| Concerned with independent-mindedness of the ] principalities, the ] sought to curb their influence and bring them under the control of the central government in ]. However, removal from power of these hereditary principalities led to more instability in the region from the 1840s onwards. In their place, ] sheiks and religious orders rose to prominence and spread their influence throughout the region. One of the prominent Sufi leaders was ''] Nahri'', who began a revolt in the region between Lakes ] and ]. The area under his control covered both Ottoman and ] territories. Shaikh Ubaidalla is regarded as one of the earliest proponents of ]. In a letter to a ] Vice-Consul, he declared: "The Kurdish nation is a people apart... we want our affairs to be in our hands." | |||

| The diocese of Amida, in 1650, was suppressed in 1972 and immediately nominally restored as Armenian Catholic (] and language) ] of the lowest (episcopal) rank, ''Amida of the Armenians''. | |||

| ] | |||

| So far, it has had the following incumbents, of the fitting episcopal rank with an archiepiscopal exception: | |||

| In 1895 an estimated 25,000 ] and ] were ] in ], including in the city.<ref name=gunter>{{cite book|last=Gunter|first=Michael|title=The Kurdish Predicament in Iraq: A Political Analysis|year=1999|page=8|publisher=St. Martin's Press |isbn=978-0-312-21896-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fToRZfDdt4IC&pg=PA8}}</ref> At the turn of the 19th century, the Christian population of the city was mainly made up of ] and ].<ref name="JV20">{{cite book|author1=Joost Jongerden|author2=Jelle Verheij|title=Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X_LmnA75Dt8C&pg=PA20|year=2012|publisher=Brill|isbn=978-90-04-22518-3|page=20}}</ref> The city was also a site of ] during the 1915 ] and ] (see: ]); nearly 150,000 were expelled from the city to the death marches in the ].<ref name=mdumper>{{cite book|last=Dumper|first=Michael|title=Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia|year=2007|page=130|publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-1-57607-919-5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3SapTk5iGDkC&pg=PA130}}</ref> | |||

| * ], ] (I.C.P.B.) (3 January 1977 – 30 June 1986) as ] of ] (3 January 1977 – 30 June 1986); later Eparch (Bishop) of ] (France) (30 June 1986 – 2 February 2013) and ] in Western Europe of the Armenians (30 June 1986 – 8 June 2013), then ] of ] (in Beirut, Lebanon) (25 June 2015 – 25 July 2015), finally ] as ] (24 July 2015 – present) and President of Synod of the Armenian Catholic Church (25 July 2015 – present) | |||

| * Titular Archbishop Lévon Boghos Zékiyan (21 May 2014 – 21 March 2015), as ] ''sede plena'' of ] (Turkey) (21 May 2014 – 21 March 2015), later succeeded as Archeparch (Archbishop) of Istanbul of the Armenians (21 March 2015.03.21 – present) and President of Episcopal Conference of Turkey (April 2015 – present) | |||

| * Kévork Assadourian (5 September 2015 – present), ] of ]; no previous prelature | |||

| === Republic of Turkey === | |||

| In January 1928, Diyarbakır became the center of the ], a regional subdivision for an area containing the provinces of ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. In a reorganization of the provinces in 1952, Diyarbakır city was made the administrative capital of the ]. In 1993, Diyarbakir was established as a Metropolitan Municipality.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ekanun.net/504-sayili-kanun-hukmunde-kararname/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140203173501/http://www.ekanun.net/504-sayili-kanun-hukmunde-kararname/|archive-date=2014-02-03|title=504 Sayılı Kanun Hükmünde Kararname {{!}} Kanunlar|date=2014-02-03|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> Its districts are ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.sabah.com.tr/secim/31-mart-2019-yerel-secim-sonuclari/diyarbakir/ili-yerel-secim-sonuclari|title=Diyarbakır Seçim Sonuçları – 31 Mart 2019 Yerel Seçimleri|website=sabah.com.tr|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> | |||

| Established in 1963 as ] of the highest (Metropolitan) rank, '''Amida of the Syriacs'''. | |||

| The American-Turkish ] Air Force Base near Diyarbakır was operational from 1956 to 1997. | |||

| It has been vacant for decades, having had the following incumbent of Metropolitan rank; | |||

| * Titular Archbishop Flavien Zacharie Melki (6 July 1963 – 30 November 1989), as ] of ] (6 July 1963 – death 1983) | |||

| Diyarbakır has seen much violence in recent years, involving Turkish security forces, the ] (PKK), and the ] (ISIL).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/death-toll-in-hdp-diyarbakir-rally-rises-to-three-83722|title=Death toll in HDP Diyarbakır rally rises to three – Turkey News|website=Hürriyet Daily News|date=10 June 2015 |language=en|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.euronews.com/2016/11/04/isil-claims-responsibility-for-a-deadly-car-bomb-attack-in-diyarbakir-southeast-turkey-local-officials-initially-suggested-the-outlawed-pkk-was-to-blame|title=ISIL claims Diyarbakir bombing days after 'al-Baghdadi urged attacks on Turkey'|date=2016-11-04|website=euronews|language=en|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/01/bomb-blast-kills-policemen-turkey-diyarbakir-170116154441718.html|title=Roadside bomb blast kills police in Turkey's Diyarbakir|website=www.aljazeera.com|access-date=2020-01-23}}</ref> Between 8 November 2015 and 15 May 2016 ] in fighting between the ] and the PKK.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://nos.nl/l/2107647|title=Vernietiging Turkse steden veel groter dan gedacht|first=Lucas Waagmeestercorrespondent in|last=Turkije|website=nos.nl|date=27 May 2016 }}</ref> In early November 2015, Kurdish lawyer and human rights activist ] was killed in the Sur district during a press statement in which he had been calling for a de-escalation in violence between the PKK and the Turkish state.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-12-13 |title=Report – Investigation of the audio-visual material included in the case file of the killing of Tahir Elçi |url=https://content.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FA-TE-Report_12_English_public.pdf |access-date=2023-09-24 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| {{see also|Diyar Bakr}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In 639, the city was captured by the ], and introduced the religion of ]. The city passed under ] and then ] control, but with the progressive fragmentation of the Abbasid Caliphate from the late 9th century, it periodically came under the rule of autonomous dynasties. ] and his descendants ruled the city and the wider ] from 871 until 899, when Caliph ] restored Abbasid control, but the area soon passed to another local dynasty, the ]. The latter were displaced by the ] in 978, who were in turn followed by the ] a few years later. The Marwanids ruled until after the ] in 1071, when the city came under the rule of the ] branch of the ] and then the ] of the ]. The whole area was then disputed between the ] and ] dynasties for a century, after which it was taken over by the competing Turkic federations of the ] (the Black Sheep) first and then the ] until the rise of the Persian ], who naturally took over the city and the wider region. | |||

| ] in the ] (2010 photo)]] | |||

| ===Safavids and Ottomans=== | |||

| A 2018 report by Arkeologlar Derneği İstanbul found that, since 2015, 72% of the city's historic ] had been destroyed through demolition and redevelopment, and that laws designed to protect historic monuments had been ignored. They found that the city's "urban regeneration" policy was one of demolition and redevelopment rather than one of repairing cultural assets damaged during the recent civil conflict, and because of that many registered historic buildings had been completely destroyed. The extent of the loss of non-registered historic structures is unknown because any historic building fragments revealed during the demolition of modern structures were also demolished.<ref name="arkeologlardernegist.org">{{Cite web|url=https://www.arkeologlardernegist.org/aciklama.php?id=31|title=Açıklama|website=www.arkeologlardernegist.org}}</ref> As of 2021, large parts of the city and district were restored and government officials were looking towards tourism again.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.diyarbakirsoz.com/diyarbakir/hedef-5-milyon-turist-getirmek-221044|title=Hedef 5 milyon turist getirmek|date=19 March 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.haberturk.com/diyarbakir-haberleri/85587349-tarihi-diriltecek-dev-projenin-2-etabi-basladiunesco-dunya-kultur-mirasi-listesinde-bulunan|title=Tarihi diriltecek dev projenin 2. Etabı başladı unesco dünya kültür mirası listesinde bulunan diyarbakır surlarının 2. Etap projesi başladı yaklaşık 14 milyon liraya mal olacak olan restorasyon çalışmalarının 500 gün süreceği öğrenildi - Diyarbakır Haberleri|date=17 March 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ensonhaber.com/emlak/emlak-projeleri/teroristlerin-yiktigi-suru-devlet-ayaga-kaldirdi|title = Teröristlerin yıktığı Sur'u devlet ayağa kaldırdı| date=18 March 2021 }}</ref><ref name=":10" /> | |||

| {{see also|Diyarbekir Eyalet|Diyarbekir Vilayet}}During ] rule, the government began to assert its authority in the region in the early 19th century. Concerned with independent-mindedness of ] principalities, Ottomans sought to curb their influence and bring them under the control of the central government in Constantinople. However, removal from power of these hereditary principalities led to more instability in the region from the 1840s onwards. In their place, ] sheiks and religious orders rose to prominence and spread their influence throughout the region. One of the prominent Sufi leaders was ''Shaikh Ubaidalla Nahri'', who began a revolt in the region between Lakes ] and ]. The area under his control covered both Ottoman and ] territories. Shaikh Ubaidalla is regarded as one of the earliest leaders who pursued modern nationalist ideas among Kurds. In a letter to a British Vice-Consul, he declared: ''the Kurdish nation is a people apart... we want our affairs to be in our hands'.''' | |||

| Many residences and buildings collapsed or suffered substantial damage in the ] around 200 miles (300 km) from the epicentre.<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Robles |first1=Pablo |last2=Chang |first2=Agnes |last3=Holder |first3=Josh |last4=Leatherby |first4=Lauren |last5=Reinhard |first5=Scott |last6=Wu |first6=Ashley |date=2023-02-06 |title=Mapping the Damage From the Earthquake in Turkey and Syria |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/02/06/world/turkey-earthquake-damage.html |access-date=2023-02-14 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=2023-02-06 |title=The earthquake's widespread destruction, in photos, maps and videos |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/02/06/turkey-syria-earthquake-map-photos-videos/ |access-date=2023-02-14 |newspaper=Washington Post |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Ozdal |first=Umit |date=2023-02-06 |title=After huge Turkey quake, Diyarbakir residents pray for missing families |language=en |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/after-huge-turkey-quake-diyarbakir-residents-pray-missing-families-2023-02-06/ |access-date=2023-02-14}}</ref> A Turkish professor and former journalist from the country commented, "It is like having an epicenter of an earthquake in ] and buildings in New York City are collapsing."<ref>{{Cite web |date=February 7, 2023 |title=Lebanon County professor reacts to deadly earthquakes in Turkey and Syria |url=https://www.fox43.com/article/news/local/professor-deadly-earthquakes-turkey-syria-lebanon-valley-college-professor/521-c8971a30-a39f-4911-b843-d4ad5b41dcdb |access-date=2023-02-14 |website=fox43.com |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| The breakup of the Ottoman Empire after its defeat in the ] led to its dismemberment and establishment of the present-day political boundaries, dividing the Kurdish-inhabited regions between several newly created states. The establishment and enforcement of the new borders had profound effects for the Kurds, who had to abandon their traditional nomadism for village life and settled farming.] | |||

| == Sports == | |||

| Between the early 16th century and mid-to late 17th century the city and the much wider Eastern Anatolia region (comprising ] and ]) was being heavily competed between the rivalling ] and the Ottoman Turks, being passed on numerous times between the two archrivals. When it was firstly conquered by the ] in the 16th century by the campaigns of Bıyıklı Mehmet Paşa under the rule of Sultan ] following the ], they established an ] with its centre in Diyarbakır. The Ottoman eyelet of Diyarbakır corresponded to Turkey's southeastern provinces today, a rectangular area between the ] to ] and from the southern shores of ] to ] and the beginnings of the ], although its borders saw some changes over time. The city was an important military base for controlling this region and at the same time a thriving city noted for its craftsmen, producing glass and metalwork. For example, the doors of ]'s tomb in ] were made in Diyarbakır, as were the gold and silver decorated doors of the tomb of ] in ]. | |||

| The most notable ] clubs of the city are ] (established 1968) and ] (established 1990),<ref>{{cite news|title=Turkish court acquits German footballer Naki in Kurdish case|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37908775|date=8 November 2016|work=BBC}}</ref> with ] being one of the most notable footballers from the city. The women's football team ] were promoted at the end of the 2016–17 ] season to the ].<ref name="m1" /> | |||

| Ottoman rule was confirmed by the ] of 1555 which followed after the ]. However, a recapture of the city followed by Safavid Persia, ruled by shah ], during the ]. Diyarbakır was retaken by the Safavids once again in 1623-1624, during the ].{{sfn|Faroqhi|2009|page=91}} | |||

| == Politics == | |||

| In 1895 an estimated 25,000 ] and ] were ] in Diyarbakır vilayet, including the city.<ref name=gunter>{{cite book|last=Gunter|first=Michael|title=The Kurdish Predicament in Iraq: A Political Analysis|page=8|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fToRZfDdt4IC&pg=PA8}}</ref> At the turn of the 19th century, the Christian population of the city was mainly made up of Armenians and ].<ref name="JV20">{{cite book|author1=Joost Jongerden|author2=Jelle Verheij|title=Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X_LmnA75Dt8C&pg=PA20|year=2012|publisher=BRILL|isbn=90-04-22518-8|p=20}}</ref> The city was also a site of ] of Armenians and Assyrians in 1915; nearly 150,000 were deported from the city.<ref name=mdumper>{{cite book|last=Dumper|first=Michael|title=Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia|page=130|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3SapTk5iGDkC&pg=PA130}}</ref> | |||

| In the ], ] and ] of the ] (BDP) were elected co-mayors of Diyarbakır. However, on 25 October 2016, both were detained by Turkish authorities "on thinly supported charges of being a member of the ] (PKK)".<ref name=fury>{{cite news|title=Fury erupts after mayors detained in Turkey's Kurdish southeast|date=26 October 2016|publisher=Al-Monitor|url=http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/10/turkey-arrest-mayors-diyarbakir-kurdish.html}}</ref> The Turkish government ordered a general internet blackout after the arrest.<ref>{{cite news|title=Slowdown in access to social media in Turkey a 'security measure,' says PM|date=4 November 2016|publisher=Hurriyet Daily News|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/problems-in-access-to-social-media-in-turkey-a-security-measure-says-pm.aspx?pageID=238&nID=105744&NewsCatID=509}}</ref> Nevertheless, on 26 October, several thousand demonstrators at Diyarbakir city hall demanded the mayors' release.<ref name=fury /> Some days later, the Turkish government appointed an unelected state trustee as the mayor.<ref>{{cite news|title=Turkey appoints trustee as Diyarbakir mayor after arrests|date=1 November 2016|publisher=France24|url=http://www.france24.com/en/20161101-turkey-appoints-trustee-diyarbakir-mayor-after-arrests|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130184727/http://www.france24.com/en/20161101-turkey-appoints-trustee-diyarbakir-mayor-after-arrests|archive-date=30 November 2016}}</ref> In November, public prosecutors demanded a 230-year prison sentence for Kışanak.<ref>{{cite news|title=Prosecutors demand 230 years prison sentences for ousted Diyarbakır Co-Mayor Kışanak|date=29 November 2016|publisher=Hurriyet Daily News|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/prosecutors-demand-230-years-prison-sentences-for-ousted-diyarbakir-co-mayor-kisanak.aspx?pageID=238&nID=106702&NewsCatID=509}}</ref> | |||

| In January 2017, the un-elected state trustee appointed by the Turkish government ordered the removal of the ] sculpture of a mythological winged bull from the town hall, which had been erected by the BDP mayors to commemorate the Assyrian history of the town and its still resident Assyrian minority. All Kurdish language street signs were also removed, alongside the shutting down of organisations concerned with Kurdish language and culture, removal of Kurdish names from public parks, and removal of Kurdish cultural monuments and linguistic symbols.<ref>{{cite news|title=Turkey remove Assyrian sculpture from front of local city hall|date=17 January 2017|publisher=Almasdar News|url=https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/turkey-remove-assyrian-sculpture-from-front-of-local-city-hall/}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Kurdish language signs removed from Diyarbakır streets|url=https://ahvalnews.com/turkey-kurds/kurdish-language-signs-removed-diyarbakir-streets|access-date=2021-02-20|website=Ahval|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Republic of Turkey=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] and extended by ] between 367 and 375, stretch almost unbroken for about 6 kilometres.]] | |||

| In the ], ] of the ] party was elected mayor of Diyarbakir.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://secim.haberler.com/2019/yerel-secimler/diyarbakir-secim-sonuclari/|title=Diyarbakır Seçim Sonuçları – 31 Mart Diyarbakır Yerel Seçim Sonuçları|website=secim.haberler.com|language=tr-TR|access-date=2019-05-20}}</ref> In August 2019 he was dismissed and subsequently sentenced to 9 years and 4 months imprisonment accused of supporting terrorism as part of a government crackdown against politicians of the ] ] party; the Turkish state appointed ] in his place.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/three-pro-kurdish-mayors-replaced-southeastern-turkey|title=Three pro-Kurdish mayors replaced in southeastern Turkey|website=Middle East Eye|language=en|access-date=2019-08-19}}</ref> Other Kurdish mayors in Kurdish cities across the region also suffered a similar fate, with ] vowing to remove any future Kurdish mayors too.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-02-07|title=Turkey: Kurdish Mayors' Removal Violates Voters' Rights|url=https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/02/07/turkey-kurdish-mayors-removal-violates-voters-rights|access-date=2021-04-02|website=Human Rights Watch|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Erdogan vows re-seizure of Kurdish municipalities should HDP win local elections|url=https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/17616-Erdogan-vows-re-seizure-of-Kurdish-municipalities-should-HDP-win-local-elections|access-date=2021-04-02|website=www.kurdistan24.net|language=en}}</ref> Protests against the decision arose which were suppressed by the Turkish police with the use of water cannons; some protestors were killed.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Turkey: Police and militias killing of Kurdish protesters must be investigated and prosecuted|url=https://primarysources.brillonline.com/browse/human-rights-documents-online/turkey-police-and-militias-killing-of-kurdish-protesters-must-be-investigated-and-prosecuted;hrdhrd00352014132 |url-access=subscription |website=Brill: Human Rights Documents online|doi=10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-0035-2014132}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gunes|first=Cengiz|date=2014-01-01|title=Kurdish Political Activism in Turkey: An Overview|journal=Singapore Middle East Papers|doi=10.23976/smep.2014008}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Three pro-Kurdish mayors replaced in southeastern Turkey|url=http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/three-pro-kurdish-mayors-replaced-southeastern-turkey|access-date=2021-04-02|website=Middle East Eye|language=en}}</ref> ] has become home to many ]s, mainly ] accused of terrorism charges by the Turkish state. Inmates have been subject to torture, rape, humiliation, beating, murder and other abuses.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hakyemez|first=Serra|date=2017|title=Margins of the Archive: Torture, Heroism, and the Ordinary in Prison No. 5, Turkey|journal=Anthropological Quarterly|volume=90|issue=1|pages=107–138|doi=10.1353/anq.2017.0004|s2cid=152237485|issn=1534-1518}}</ref> | |||

| In the reorganization of the provinces, Diyarbakır was made administrative capital of the ]. In 1993 Diyarbakir was established as a Metropolitan Municipality.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140203173501/http://www.ekanun.net/504-sayili-kanun-hukmunde-kararname/#|title=504 Sayılı Kanun Hükmünde Kararname {{!}} Kanunlar|date=2014-02-03|website=web.archive.org|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> Its districts are ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.sabah.com.tr/secim/31-mart-2019-yerel-secim-sonuclari/diyarbakir/ili-yerel-secim-sonuclari|title=Diyarbakır Seçim Sonuçları - 31 Mart 2019 Yerel Seçimleri|website=sabah.com.tr|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> | |||

| == Economy == | |||

| During the 1980s and 1990s, at the peak of the ] (PKK) insurgency, the population of the city grew dramatically as villagers from remote areas where fighting was serious left or were forced to leave for the relative security of the city. After the cessation of hostilities between the PKK and the Turkish army, a large degree of normality returned to the city, with the Turkish government declaring an end to the 15-year period of emergency rule on 30 November 2002. Diyarbakır grew from a population of 30,000 in the 1930s to 65,000 by 1956, to 140,000 by 1970, to 400,000 by 1990,<ref name="McDowall2004">{{cite book|author = McDowall, David|year = 2004| publisher = IB Tauris| isbn = 978-1-85043-416-0| title = A Modern History of the Kurds| page = 403| editor = 3E| url = https://books.google.com/?id=dgDi9qFT41oC&pg=PA403&vq=30,000}}</ref> and eventually swelled to about 1.5 million by 1997.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kirişci, Kemal|authorlink=Kemal Kirişci|date=June 1998|chapter=Turkey|editor=Janie Hampton|title=Internally Displaced People: A Global Survey|location=London|publisher=Earthscan Publications Ltd|pages=198, 199}}</ref> | |||

| Historically, Diyarbakır produced ] and ].<ref name=Prothero60 /><ref name=Prothero62 /> They would preserve the wheat in ]s, with coverings of ] and twigs from ] trees. This system would allow the wheat to be preserved for up to ten years.<ref name=Prothero60>{{cite book|last=Prothero|first=W.G.|title=Armenia and Kurdistan|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|location=London|page=60|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/11768/view/1/60/}}</ref><ref name=":10" /> In the late 19th and early 20th century, Diyarbakır exported ]s, ]s, and ]s to Europe.<ref name=Prothero62>{{cite book|last=Prothero|first=W.G.|title=Armenia and Kurdistan|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|location=London|page=62|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/11768/view/1/62/}}</ref> ]s were raised, and wool and ] was exported from Diyarbakır. Merchants would also come from ], ], and ], to purchase goats and ].<ref name=Prothero63>{{cite book|last=Prothero|first=W.G.|title=Armenia and Kurdistan|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|location=London|page=63|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/11768/view/1/63/}}</ref> ] was also produced, but not so much exported, but used by locals. ] was observed in the area, too.<ref name=Prothero64>{{cite book|last=Prothero|first=W.G.|title=Armenia and Kurdistan|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|location=London|page=64|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/11768/view/1/64/}}</ref> | |||

| Prior to World War I, Diyarbakır had an active ] industry, with six mines. Three were active, with two being owned by locals and the third being owned by the Turkish government. ] was the primary type of copper mined. It was mined by hand by Kurds. A large portion of the ore was exported to England. The region also produced ], ], ], ], ], ], and ], but primarily for local use.<ref name=Prothero70>{{cite book|last=Prothero|first=W.G.|title=Armenia and Kurdistan|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|location=London|page=70|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/11768/view/1/70/}}</ref> | |||

| The 41-year-old American-Turkish ] Air Force Base near Diyarbakır, known as NATO's frontier post for monitoring the former Soviet Union and the Middle East, closed on 30 September 1997. This closure was the result of the general drawdown of US bases in Europe and the improvement in space surveillance technology. The base housed sensitive electronic intelligence-gathering systems that monitored the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Russia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.globalsecurity.org/space/facility/pirinclik.htm|title=Diyarbakir - Pirinclik|author=|date=|website=globalsecurity.org}}</ref> | |||

| The city is served by ] and ]. In 1935 the railway between ] and Diyarbakır was inaugurated.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kezer|first=Zeynep|date=2014|title=Spatializing Difference: The Making of an Internal Border in Early Republican Elazığ, Turkey|journal=Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians|volume=73|issue=4|page=516|doi=10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.507|jstor=10.1525/jsah.2014.73.4.507|issn=0037-9808}}</ref> | |||

| According to a November 2006 survey by the Sur Municipality, 72% of the inhabitants of the municipality use ] most often in their daily speech, followed by ],<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=205469|accessdate=2008-08-06|title=Belediye Diyarbakırlıyı tanıdı: Kürtçe konuşuyor|work=]|agency=Dogan News Agency|date=2006-11-24|language=Turkish|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070930221904/http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=205469|archivedate=30 September 2007|df=dmy-all}}</ref> with small minorities of ], ] and ]s still resident. After World War II, as the Kurdish population moved to urban centres, Diyarbakir gradually became predominantly Kurdish.<ref name="HeperSayari2013">{{cite book|author1=Metin Heper|author2=Sabri Sayari|title=The Routledge Handbook of Modern Turkey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3i4FPE1s9aYC&pg=PA247|date=7 May 2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-30964-9|page=247|quote=It was thus only in recent times that Diyarbakır, the unofficial capital of Turkey's Kurdish area, became a predominantly Kurdish town.}}</ref> | |||

| == Demographics == | |||

| Diyarbakır has been the victim of terror attacks in recent years. In 2008, a ] in the city, killing five people, a blast for which nobody claimed responsibility. In 2015, ] of the ] was targeted, killing three people and injuring over 100.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/death-toll-in-hdp-diyarbakir-rally-rises-to-three-83722|title=Death toll in HDP Diyarbakır rally rises to three - Turkey News|website=Hürriyet Daily News|language=en|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> And in 2016, ] in February and March, each killing six people. In November 2016 ISIL perpetrated an attack that killed 9 people and wounded more than 100.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.euronews.com/2016/11/04/isil-claims-responsibility-for-a-deadly-car-bomb-attack-in-diyarbakir-southeast-turkey-local-officials-initially-suggested-the-outlawed-pkk-was-to-blame|title=ISIL claims Diyarbakir bombing days after 'al-Baghdadi urged attacks on Turkey'|date=2016-11-04|website=euronews|language=en|access-date=2019-11-10}}</ref> | |||

| {{expand section|date=March 2021}} | |||

| At the turn of the 19th century, the Christian population of the city was mainly made up of Armenians and Assyrians.<ref name="JV20" /> The Assyrian and Armenian presence dates to antiquity.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Goodspeed|first1=George|title=A History of the Babylonians and Assyrians, Volume 6|date=1902}}</ref> There was also a small Jewish community in the city.<ref name="suryaniler.com"> Konu: Diyarbakır Tarihi ve Demografik Yapısı</ref> All Christians spoke Armenian and Kurdish. Notables spoke Turkish. In the streets, the language was Kurdish.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Kaza Diyarbekir / Diyarbakır / Āmīd / Omīd ܐܡܝܕ |url=https://virtual-genocide-memorial.de/region/the-six-provinces/diyarbakir-vilayet/sancak-diyarbekir-diyarbakir/kaza-diyarbekir-diyarbakir/ |access-date=2023-09-18 |website=Virtual Genocide Memorial |language=en-US}}</ref> According to the ] from 1911, the population numbered 38 thousand, almost half being Christian and consisting of Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Turkomans, Armenians, Chaldeans, Jacobites, and a few Greeks.<ref>{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Diarbekr |volume=8 |last=Maunsell |first=Francis Richard |author-link=Francis Richard Maunsell | page =167}}</ref> During the Governorship of ] in the ], the Armenian population of Diyarbakir was resettled and exterminated.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Üngör|first=Ugur Ümit|author-link=Uğur Ümit Üngör|date=2012|title=Rethinking the Violence of Pacification: State Formation and Bandits in Turkey, 1914–1937|journal=Comparative Studies in Society and History|volume=54|issue=4|page=754|doi=10.1017/S0010417512000400|jstor=23274550|s2cid=147038615|issn=0010-4175}}</ref> | |||

| After World War II, as the Kurdish population moved from the villages and mountains to urban centres, Diyarbakir's Kurdish population continued to grow.<ref name="HeperSayari2013">{{cite book|author1=Metin Heper|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3i4FPE1s9aYC&pg=PA247|title=The Routledge Handbook of Modern Turkey|author2=Sabri Sayari|date=7 May 2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-30964-9|page=247|quote=It was thus only in recent times that Diyarbakır, the unofficial capital of Turkey's Kurdish area, became a predominantly Kurdish town.}}</ref> Diyarbakır grew from a population of 30,000 in the 1930s to 65,000 by 1956, to 140,000 by 1970, to 400,000 by 1990,<ref name="McDowall2004">{{cite book |author=McDowall, David |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dgDi9qFT41oC&q=30,000&pg=PA403 |title=A Modern History of the Kurds |publisher=IB Tauris |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-85043-416-0 |page=403}}</ref> and eventually swelled to about 1.5 million by 1997.<ref>{{cite book |author=Kirişci, Kemal |title=Internally Displaced People: A Global Survey |date=June 1998 |publisher=Earthscan Publications Ltd |editor=Janie Hampton |location=London |pages=198, 199 |chapter=Turkey |author-link=Kemal Kirişci}}</ref> During the 1990s, the city grew dramatically due to the immigrant population from thousands of ] during the ].<ref>{{Citation |last=Houston |first=Christopher |title=Creating a Diaspora within a Country: Kurds in Turkey |date=2005 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World |pages=403–414 |editor-last=Ember |editor-first=Melvin |location=Boston, MA |publisher=Springer US |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-0-387-29904-4_40 |isbn=978-0-387-29904-4 |editor2-last=Ember |editor2-first=Carol R. |editor3-last=Skoggard |editor3-first=Ian}}</ref> | |||

| Between 8 November 2015 and 15 May 2016 ] in fighting between the Turkish military and the PKK.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://nos.nl/l/2107647|title=Vernietiging Turkse steden veel groter dan gedacht|first=Lucas Waagmeestercorrespondent in|last=Turkije|date=|website=nos.nl}}</ref> | |||

| According to a November 2006 survey by the Sûr Municipality, 72% of the inhabitants of the municipality use ] most often in their daily speech due to the overwhelming Kurdish majority in the city, followed by minorities of ], ] and ].<ref name=":4">{{cite news|date=2006-11-24|title=Belediye Diyarbakırlıyı tanıdı: Kürtçe konuşuyor|language=tr|work=]|agency=Dogan News Agency|url=http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=205469|access-date=2008-08-06|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070930221904/http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=205469|archive-date=30 September 2007}}</ref> | |||

| A 2018 report by Arkeologlar Derneği İstanbul found that, since 2015, 72% of the city's historic Sur district had been destroyed through demolition and redevelopment, and that laws designed to protect historic monuments had been ignored. They found that the city's "urban regeneration" policy was one of demolition and redevelopment rather than one of repairing cultural assets damaged during the recent civil conflict, and because of that many registered historic buildings had been completely destroyed. The extent of the loss of non-registered historic structures is unknown because any historic building fragments revealed during the demolition of modern structures were also demolished.<ref name="arkeologlardernegist.org"></ref> | |||

| There are some ] ] villages around Diyarbakır's ], but there are no official reports about their population numbers.<ref name="suryaniler.com" /><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161121051835/http://www.alevinet.com/diyarbakir-alevi-turkmen-koyleri/|date=21 November 2016}} Diyarbakır Alevi-Türkmen köyleri</ref> | |||

| ==Sports== | |||

| The most notable ] clubs of the city are ] (established 1968) and ] (established 1990).<ref>{{cite news|title=Turkish court acquits German footballer Naki in Kurdish case|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37908775|date=8 November 2016|work=BBC}}</ref> | |||

| There have been attempts by Turkish lawmakers to deny Diyarbakır's Kurdish majority identity,<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Yeğen|first=Mesut|date=April 1996|title=The Turkish state discourse and the exclusion of Kurdish identity|journal=Middle Eastern Studies|volume=32|issue=2|pages=216–229|doi=10.1080/00263209608701112|issn=0026-3206}}</ref> with ] releasing a school book named "Our City, Diyarbakir" ("''Şehrimiz Diyarbakır"'' ]) on ] in which it claims that a ] similar to that spoken in ] is spoken in the city along with regional languages like ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|last=Gazetesi|first=Evrensel|title=MEB'e göre Diyarbakır'da Kürtçe değil, Azericeye benzeyen bir Türkçe konuşuluyor|url=https://www.evrensel.net/haber/428480/mebe-gore-diyarbakirda-kurtce-degil-azericeye-benzeyen-bir-turkce-konusuluyor|access-date=2021-03-23|website=Evrensel.net|language=tr-TR}}</ref><ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite web|title='Baku Turkish' spoken in Kurdish-majority Diyarbakır, according to Ministry|url=https://www.bianet.org/english/education/241080-baku-turkish-spoken-in-kurdish-majority-diyarbakir-according-to-ministry|access-date=2021-03-19|website=Bianet – Bagimsiz Iletisim Agi}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Şehrimiz Diyarbakır|url=http://diyarbakir.meb.gov.tr/kitap/Sehrimiz_Diyarbakir.pdf|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210217134102/http://diyarbakir.meb.gov.tr/kitap/Sehrimiz_Diyarbakir.pdf|archive-date=17 Feb 2021}}</ref> Critics link this to a general trend towards ] in Turkey.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| The women's football team ] were promoted at the end of the 2016–17 ] season to the ].<ref name="m1"/> | |||

| == |

== Culture == | ||

| There is local jewelry making and other craftwork in the area. Folk dancing to the drum and ] (pipe) are a part of weddings and celebrations in the area. The Diyarbakir Municipality Theatre was founded in 1990, and had to close its doors in 1995.<ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Çelik |first=Duygu |title=Kurdish Art and Identity |chapter=The Impact of the Dengbêjî Tradition on Kurdish Theater in Turkey |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110599626-005/pdf |chapter-url-access=subscription |publisher=] |year=2020 |pages=106–107|doi=10.1515/9783110599626-005 |isbn=978-3-11-059962-6 |s2cid=241540342 }}</ref> It was re-opened in 1999,<ref name=":6" /> under Mayor ]. It was closed down in 2016 after the dismissal of the mayor in 2016.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=Tzabiras |first=Marianna |date=2017-01-05 |title=Turkey's state of emergency puts Kurdish theatre in a chokehold |url=https://ifex.org/turkeys-state-of-emergency-puts-kurdish-theatre-in-a-chokehold/ |access-date=2022-08-16 |website=IFEX |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Çelik |first=Duygu Ç |title=Kurdish Art and Identity |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110599626-005/html |chapter=The Impact of the Dengbêjî Tradition on Kurdish Theater in Turkey |date=2020-09-07 |pages=96–118 |publisher=De Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-059962-6 |language=en |doi=10.1515/9783110599626-005|s2cid=241540342 }}</ref> The Municipality City Theatre also ].<ref name=":5" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Verstraete |first=Peter |title='Acting' under Turkey's State of Emergency |url=https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/158954846/155_Article_Text_929_1_10_20190121.pdf |website=] |page=64}}</ref> | |||

| In the ], ] and ] of the ] (BDP) were elected co-mayors of Diyarbakır. However, on 25 October 2016, both were detained by Turkish authorities "on thinly supported charges of being a member of the ] (PKK)".<ref name=fury>{{cite news|title=Fury erupts after mayors detained in Turkey's Kurdish southeast|date=26 October 2016|publisher=Al-Monitor|url=http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/10/turkey-arrest-mayors-diyarbakir-kurdish.html}}</ref> The Turkish government ordered a general internet blackout after the arrest.<ref>{{cite news|title=Slowdown in access to social media in Turkey a ‘security measure,’ says PM|date=4 November 2016|publisher=Hurriyet Daily News|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/problems-in-access-to-social-media-in-turkey-a-security-measure-says-pm.aspx?pageID=238&nID=105744&NewsCatID=509}}</ref> Nevertheless, on 26 October, several thousand demonstrators at Diyarbakir city hall demanded the mayors’ release.<ref name=fury/> Some days later, the Turkish government appointed an unelected state trustee as the mayor.<ref>{{cite news|title=Turkey appoints trustee as Diyarbakir mayor after arrests|date=1 November 2016|publisher=France24|url=http://www.france24.com/en/20161101-turkey-appoints-trustee-diyarbakir-mayor-after-arrests|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161130184727/http://www.france24.com/en/20161101-turkey-appoints-trustee-diyarbakir-mayor-after-arrests|archivedate=30 November 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In November, public prosecutors demanded a 230-year prison sentence for Kışanak.<ref>{{cite news|title=Prosecutors demand 230 years prison sentences for ousted Diyarbakır Co-Mayor Kışanak|date=29 November 2016|publisher=Hurriyet Daily News|url=http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/prosecutors-demand-230-years-prison-sentences-for-ousted-diyarbakir-co-mayor-kisanak.aspx?pageID=238&nID=106702&NewsCatID=509}}</ref> | |||

| One of the other common celebrations in Turkey is ]. This celebration is done on the pretext of the beginning of spring and the beginning of the ]. The establishment of Nowruz has a long history, so much so that it has been celebrated in different parts of ] for the past three thousand years, especially in the ]. In different parts of Turkey, especially the ] of this country, Nowruz is considered one of the most important cultural and historical traditions of these regions. Lighting a fire, wearing new clothes, holding a dance ceremony, and giving gifts to each other are some of the activities that are done in this celebration.<ref name=":10" /><ref>{{Cite news |last1=Wilks |first1=Andrew |date=2022-03-29 |title=Possible closure of political party dampens Nowruz for Turkey's Kurds |url=https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/03/possible-closure-political-party-dampens-nowruz-turkeys-kurds |access-date=2023-10-06 |work=Al-Monitor |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=english.alarabiya.net/perspective/Nowruz-celebrations-in-Turkey |url=https://english.alarabiya.net/perspective/2014/03/21/Nowruz-celebrations-in-Turkey}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Nations |first=United |title=International Nowruz Day |url=https://www.un.org/en/observances/international-nowruz-day |access-date=2023-10-06 |website=United Nations |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2017-03-20 |title=Kurdish Activists Arrested in Turkey Ahead of Nowruz Celebrations |url=https://www.voanews.com/a/kurdish-activisis-arrested-turkey-nowruz-celebrations/3774111.html |access-date=2023-10-06 |website=VOA |language=en}}</ref> | |||