| Revision as of 18:54, 9 April 2021 editClueBot NG (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,438,562 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by Mr.HelpfulSource to version by Marcocapelle. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (3943925) (Bot)Tag: Rollback← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:34, 29 April 2021 edit undo70.55.29.68 (talk) /* ETags: Reverted section blankingNext edit → | ||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

| A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirms what had long been suspected, that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> Lowering the dam by as much as {{convert|3|ft|m}} and failing to replace the discharge pipes at the base of the dam cut in half the safe discharge capacity of the dam.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> This fatal lowering of the dam greatly reduced the capacity of the main spillway and virtually eliminated the action of an emergency spillway on the western abutment. Walter Frank first documented the presence of that emergency spillway in a 1988 ASCE publication.<ref name="frank" /> The existence of the emergency spillway is supported by topographic data from 1889<ref name="Francis1891" /> which shows the western abutment to be about one foot lower than the crest of the dam remnants, even after the dam had previously been lowered as much as 3 feet by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> Adding the width of the emergency spillway to that of the main spillway yields the total width of spillway (wasteway) capacity that had been specified in the 1847 design of William Morris, a State Engineer. | A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirms what had long been suspected, that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> Lowering the dam by as much as {{convert|3|ft|m}} and failing to replace the discharge pipes at the base of the dam cut in half the safe discharge capacity of the dam.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> This fatal lowering of the dam greatly reduced the capacity of the main spillway and virtually eliminated the action of an emergency spillway on the western abutment. Walter Frank first documented the presence of that emergency spillway in a 1988 ASCE publication.<ref name="frank" /> The existence of the emergency spillway is supported by topographic data from 1889<ref name="Francis1891" /> which shows the western abutment to be about one foot lower than the crest of the dam remnants, even after the dam had previously been lowered as much as 3 feet by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.<ref name="Colemanetal2016" /> Adding the width of the emergency spillway to that of the main spillway yields the total width of spillway (wasteway) capacity that had been specified in the 1847 design of William Morris, a State Engineer. | ||

| ===Effect on the development of American law=== | |||

| Survivors were unable to recover damages in court because of the club's ample resources. First, the wealthy club owners had designed the club's financial structure to keep their personal assets separated from it and, secondly, it was difficult for any suit to prove that any particular owner had behaved negligently. Though the former reason was probably more central to the failure of survivors' suits against the club, the latter received coverage and extensive criticism in the national press. | |||

| As a result of this criticism, in the 1890s, state courts around the country adopted '']'', a British common-law precedent which had formerly been largely ignored in the United States. State courts' adoption of ''Rylands'', which held that a non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land, foreshadowed the legal system's 20th-century acceptance of ].<ref>{{cite journal|first=Jed Handelsman |last=Shugerman |title=Note: The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of ''Fletcher v. Rylands'' in the Gilded Age|journal=Yale Law Journal|volume=110 |number=2 |pages=333–377| date=2000 |url=https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/the-floodgates-of-strict-liability-bursting-reservoirs-and-the-adoption-of-ligfletcher-v-rylandslig-in-the-gilded-age|doi=10.2307/797576 |jstor=797576 }}</ref> | |||

| =={{Anchor|Legacy}} Legacy and popular culture== | =={{Anchor|Legacy}} Legacy and popular culture== | ||

Revision as of 20:34, 29 April 2021

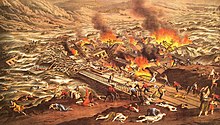

For other uses, see Johnstown Flood (disambiguation). Massive flood of Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1889 Debris above Pennsylvania Railroad bridge Debris above Pennsylvania Railroad bridge | |

| Date | May 31, 1889 |

|---|---|

| Location | South Fork, East Conemaugh, and Johnstown, Pennsylvania |

| Deaths | 2,209 or 2,208 |

| Property damage | $17 million (about $576 million today) |

The Johnstown Flood (locally, the Great Flood of 1889) occurred on Friday, May 31, 1889, after the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam, located on the south fork of the Little Conemaugh River, 14 miles (23 km) upstream of the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The dam broke after several days of extremely heavy rainfall, releasing 14.55 million cubic meters of water. With a volumetric flow rate that temporarily equaled the average flow rate of the Mississippi River, the flood killed more than 2,200 people and accounted for $17 million of damage (about $576 million in 2023 dollars).

The American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton and with 50 volunteers, undertook a major disaster relief effort. Support for victims came from all over the United States and 18 foreign countries. After the flood, survivors suffered a series of legal defeats in their attempts to recover damages from the dam's owners. Public indignation at that failure prompted the development in American law changing a fault-based regime to one of strict liability.

History

The village of Johnstown was founded in 1800 by the Swiss immigrant Joseph Johns (anglicized from "Schantz") where the Stonycreek and Little Conemaugh rivers joined to form the Conemaugh River. It began to prosper with the building of the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal in 1836 and the construction in the 1850s of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Cambria Iron Works. By 1889, Johnstown's industries had attracted numerous Welsh and German immigrants. With a population of 30,000, it was a growing industrial community known for the quality of its steel.

The high, steep hills of the narrow Conemaugh Valley and the Allegheny Mountains range to the east kept development close to the riverfront areas. The valley had large amounts of runoff from rain and snowfall. The area surrounding Johnstown is prone to flooding due to its location on the rivers, whose upstream watersheds include an extensive drainage basin of the Allegheny plateau. Adding to these factors, slag from the iron furnaces of the steel mills was dumped along the river to create more land for building. Developers' artificial narrowing of the riverbed to maximize early industries left the city even more flood-prone. The Conemaugh River, immediately downstream of Johnstown, is hemmed in by steep mountainsides for about 10 miles (16 km). A roadside plaque alongside Route 56, which follows this river, proclaims that this stretch of valley is the deepest river gorge in North America east of the Rocky Mountains.

South Fork Dam and Lake Conemaugh

High above the city, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania built the South Fork Dam between 1838 and 1853, as part of a cross-state canal system, the Main Line of Public Works. Johnstown was the eastern terminus of the Western Division Canal, supplied with water by Lake Conemaugh, the reservoir behind the dam. As railroads superseded canal barge transport, the Commonwealth abandoned the canal and sold it to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The dam and lake were part of the purchase, and the railroad sold them to private interests.

Henry Clay Frick led a group of speculators, including Benjamin Ruff, from Pittsburgh to purchase the abandoned reservoir, modify it, and convert it into a private resort lake for their wealthy associates. Many were connected through business and social links to Carnegie Steel. Development included lowering the dam to make its top wide enough to hold a road, and putting a fish screen in the spillway (the screen also trapped debris). These alterations are thought to have increased the vulnerability of the dam. Moreover, a system of relief pipes and valves, a feature of the original dam, and previously sold off for scrap, was not replaced, so the club had no way of lowering the water level in the lake in case of an emergency. The members built cottages and a clubhouse to create the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, an exclusive and private mountain retreat. Membership grew to include more than 50 wealthy Pittsburgh steel, coal, and railroad industrialists.

Lake Conemaugh at the club's site was 450 feet (140 m) in elevation above Johnstown. The lake was about 2 miles (3.2 km) long, about 1 mile (1.6 km) wide, and 60 feet (18 m) deep near the dam.

The dam was 72 feet (22 m) high and 931 feet (284 m) long. After 1881, when the club opened, the dam frequently sprang leaks. It was patched, mostly with mud and straw. There had been some speculation as to the dam's integrity, and concerns had been raised by the head of the Cambria Iron Works downstream in Johnstown.

Events of the flood

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

On May 28, 1889, a low-pressure area formed over Nebraska and Kansas. By the time this weather pattern reached western Pennsylvania two days later, it had developed into what would be termed the heaviest rainfall event that had ever been recorded in that part of the United States. The U.S. Army Signal Corps estimated that 6 to 10 inches (150 to 250 mm) of rain fell in 24 hours over the region. During the night, small creeks became roaring torrents, ripping out trees and debris. Telegraph lines were downed and rail lines were washed away. Before daybreak, the Conemaugh River that ran through Johnstown was about to overwhelm its banks.

On the morning of May 31, in a farmhouse on a hill just above the South Fork Dam, Elias Unger, president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, awoke to the sight of Lake Conemaugh swollen after a night-long heavy rainfall. Unger ran outside in the still-pouring rain to assess the situation and saw that the water was nearly cresting the dam. He quickly assembled a group of men to save the face of the dam by trying to unclog the spillway; it was blocked by the broken fish trap and debris caused by the swollen waterline. Other men tried digging a ditch at the other end of the dam, on the western abutment which was lower than the dam crest. The idea was to let more water out of the lake to try to prevent overtopping of the crest, but without success. Most remained on top of the dam, some plowing earth to raise it, while others tried to pile mud and rock on the face to save the eroding wall.

John Parke, an engineer for the South Fork Club, briefly considered cutting through the dam's end, where the pressure would be less to create another spillway, but eventually decided against it as that would have quickly ensured the failure of the dam. Twice, under orders from Unger, Parke rode on horseback to the nearby town of South Fork to the telegraph office to send warnings to Johnstown explaining the critical nature of the eroding dam. Unfortunately, Parke did not personally take a warning message to the telegraph tower - he sent a man instead. But the warnings were not passed to the authorities in town, as there had been many false alarms in the past of the South Fork Dam not holding against flooding. Unger, Parke, and the rest of the men continued working until exhausted to save the face of the dam; they abandoned their efforts at around 1:30 p.m., fearing that their efforts were futile and the dam was at risk of imminent collapse. Unger ordered all of his men to fall back to high ground on both sides of the dam where they could do nothing but watch and wait. During the day in Johnstown, the situation worsened as water rose to as high as 10 feet (3.0 m) in the streets, trapping some people in their houses.

Between 2:50 and 2:55 p.m. the South Fork Dam breached. A LiDAR analysis of the Conemaugh Lake basin reveals that it contained 14.55 million cubic meters (3.843 billion gallons) of water at the moment the dam collapsed. Modern dam-breach computer modeling reveals that it took approximately 65 minutes for most of the lake to empty after the dam began to fail. The first town to be hit by the flood was South Fork. The town was on high ground, and most of the people escaped by running up the nearby hills when they saw the dam spill over. Some 20 to 30 houses were destroyed or washed away, and four people were killed.

Continuing on its way downstream to Johnstown, 14 miles (23 km) west, the water picked up debris, such as trees, houses, and animals. At the Conemaugh Viaduct, a 78-foot (24 m) high railroad bridge, the flood was momentarily stemmed when this debris jammed against the stone bridge's arch. But within seven minutes, the viaduct collapsed, allowing the flood to resume its course. However, owing to the delay at the stone arch, the flood waters gained renewed hydraulic head, resulting in a stronger, more abrupt wave of water hitting places downstream than otherwise would have been expected. The small town of Mineral Point, one mile (1.6 km) below the Conemaugh Viaduct, was the first populated place to be hit with this renewed force. About 30 families lived on the village's single street. After the flood, there were no structures, no topsoil, no sub-soil – only the bedrock was left. The death toll here was approximately 16 people. In 2009, studies showed that the flood's flow rate through the narrow valley exceeded 420,000 cubic feet per second (12,000 m/s), comparable to the flow rate of the Mississippi River at its delta, which varies between 250,000 and 710,000 cu ft/s (7,000 and 20,000 m/s).

The village of East Conemaugh was next. One witness on high ground near the town described the water as almost obscured by debris, resembling "a huge hill rolling over and over". From his idle locomotive in the town's railyard, the engineer John Hess heard and felt the rumbling of the approaching flood. Throwing his locomotive into reverse, Hess raced backward toward East Conemaugh, the whistle blowing constantly. His warning saved many people who reached high ground. When the flood hit, it picked up the locomotive and floated it aside; Hess himself survived, but at least 50 people died, including about 25 passengers stranded on trains in the town.

Before hitting the main part of Johnstown, the flood surge hit the Cambria Iron Works at the town of Woodvale, sweeping up railroad cars and barbed wire. Of Woodvale's 1,100 residents, 314 died in the flood. Boilers exploded when the flood hit the Gautier Wire Works, causing black smoke seen by the Johnstown residents. Miles of its barbed wire became entangled in the debris in the flood waters.

Some 57 minutes after the South Fork Dam collapsed, the flood hit Johnstown. The residents were caught by surprise as the wall of water and debris bore down, traveling at 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) and reaching a height of 60 feet (18 m) in places. Some people, realizing the danger, tried to escape by running towards high ground but most people were hit by the surging floodwater. Many people were crushed by pieces of debris, and others became caught in barbed wire from the wire factory upstream and/or drowned. Those who reached attics, roofs, or managed to stay afloat on pieces of floating debris, waited hours for help to arrive.

At Johnstown, the Stone Bridge, which was a substantial arched structure, carried the Pennsylvania Railroad across the Conemaugh River. The debris carried by the flood formed a temporary dam at the bridge, resulting in the flood surge rolling upstream along the Stoney Creek River. Eventually, gravity caused the surge to return to the dam, causing a second wave to hit the city, but from a different direction. Some people who had been washed downstream became trapped in an inferno as the debris piled up against the Stone Bridge caught fire; at least 80 people died there. The fire at the Stone Bridge burned for three days. After floodwaters receded, the pile of debris at the bridge was seen to cover 30 acres (12 ha), and reached 70 feet (21 m) in height. It took workers three months to remove the mass of debris, the delay owing in part to the huge quantity of steel barbed wire from the ironworks entangled with the wreckage. Dynamite was eventually used. Still standing and in use as a railroad bridge, the Stone Bridge is a landmark associated with survival and recovery from the flood. In 2008, it was restored in a project including new lighting as part of commemorative activities related to the flood.

Aftermath

Immediately afterward

The total death toll was calculated originally as 2,209 people, making the disaster the largest loss of civilian life in the United States at the time. This number of deaths was later surpassed by fatalities in the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. However, as pointed out by David McCullough in 1968 (pages 266 and 278), a man reported as presumed dead (not known to have been found) had survived. In 1900, Leroy Temple showed up in Johnstown to reveal he had not died but had extricated himself from the flood debris at the stone bridge below Johnstown and walked out of the valley. Until 1900 Temple had been living in Beverly, Massachusetts. Therefore, the official death toll should be 2,208.

According to records compiled by The Johnstown Area Heritage Association, bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati, and as late as 1911; 99 entire families died in the flood, including 396 children; 124 women and 198 men were widowed; 98 children were orphaned; and one third of the dead, 777 people, were never identified; their remains were buried in the "Plot of the Unknown" in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont.

It was the worst flood to hit the U.S. in the 19th century. 1600 homes were destroyed, $17 million in property damage levied (approx. $497 million in 2016), and 4 square miles (10 km) of downtown Johnstown were completely destroyed. Debris at the stone bridge covered 30 acres, and clean-up operations were to continue for years. Cambria Iron and Steel's facilities were heavily damaged; they returned to full production within 18 months.

Working seven days and nights, workmen built a wooden trestle bridge to temporarily replace the huge stone railroad viaduct, which had been destroyed by the flood. The Pennsylvania Railroad restored service to Pittsburgh, 55 miles (89 km) away, by June 2. Food, clothing, medicine, and other provisions began arriving by rail. Morticians traveled by railroad. Johnstown's first call for help requested coffins and undertakers. The demolition expert "Dynamite Bill" Flinn and his 900-man crew cleared the wreckage at the Stone Bridge. They carted off debris, distributed food, and erected temporary housing. At its peak, the army of relief workers totaled about 7,000.

One of the first outsiders to arrive was Clara Barton, nurse, founder and president of the American Red Cross. Barton arrived on June 5, 1889, to lead the group's first major disaster relief effort; she did not leave for more than five months. Donations for the relief effort came from all over the United States and overseas. $3,742,818.78 was collected for the Johnstown relief effort from within the U.S. and 18 foreign countries, including Russia, Turkey, France, Great Britain, Australia, and Germany.

Frank Shomo, the last known survivor of the 1889 flood, died March 20, 1997, at the age of 108.

-

The authorities averting looting on Main Street, as drawn in Harper's Weekly, June 15, 1889

The authorities averting looting on Main Street, as drawn in Harper's Weekly, June 15, 1889

-

A house that was almost completely destroyed in the flood.

A house that was almost completely destroyed in the flood.

-

The John Schultz house at Johnstown, Pennsylvania after the flood. Skewered by a huge tree uprooted by the flood, the house floated down from its location on Union Street to the end of Main. Six people, including the owner Mr. Schultz, were inside the house when the flood hit. All survived.

The John Schultz house at Johnstown, Pennsylvania after the flood. Skewered by a huge tree uprooted by the flood, the house floated down from its location on Union Street to the end of Main. Six people, including the owner Mr. Schultz, were inside the house when the flood hit. All survived.

-

View of lower Johnstown three days after the flood

View of lower Johnstown three days after the flood

-

Main Street after flood

Main Street after flood

-

Ruins from the site of the Hulbert House

Ruins from the site of the Hulbert House

-

Copy of the preceding picture was resold 11 years later as part of the Galveston Texas storm of 1900

Copy of the preceding picture was resold 11 years later as part of the Galveston Texas storm of 1900

Subsequent floods

Floods have continued to be a concern for Johnstown, which had major flooding in 1894, 1907, 1924, 1936, and 1977. The biggest flood of the first half of the 20th century was the St. Patrick's Day Flood of March 1936. It also reached Pittsburgh, where it was known as the Great Pittsburgh Flood of 1936. Following the 1936 flood, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the river within the city and built concrete river walls, creating a channel nearly 20 feet deep. Upon completion, the Corps proclaimed Johnstown "flood free."

The new river walls withstood Hurricane Agnes in 1972, but on the night of July 19, 1977, a severe thunderstorm dropped 11 inches of rain in eight hours on the watershed above the city and the rivers began to rise. By dawn, the city was under water that reached as high as 8 feet (2.4 m). Seven counties were declared a disaster area, suffering $200 million in property damage, and 78 people died. Forty were killed by the Laurel Run Dam failure. Another 50,000 were rendered homeless as a result of this "100-year flood". Markers on a corner of City Hall at 401 Main Street show the height of the crests of the 1889, 1936, and 1977 floods.

Court case and recovery

In the years following the disaster, some people blamed the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for their modifications to the dam and failure to maintain it properly. The club had bought and redesigned the dam to turn the area into a vacation retreat in the mountains. They were accused of failing to maintain the dam properly, so that it was unable to contain the additional water of the unusually heavy rainfall.

The club was successfully defended by the firm of Knox and Reed (later Reed Smith LLP), whose partners Philander Knox and James Hay Reed were both Club members. The Club was never held legally responsible for the disaster. Knox and Reed successfully argued that the dam's failure was a natural disaster which was an Act of God, and no legal compensation was paid to the survivors of the flood. The perceived injustice aided the acceptance, in later cases, of "strict, joint, and several liability," so that even a "non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land."

Nonetheless, individual members of the club, millionaires in their day, contributed to the recovery. Along with about half of the club members, co-founder Henry Clay Frick donated thousands of dollars to the relief effort in Johnstown. After the flood, Andrew Carnegie, then known as an industrialist and philanthropist, built the town a new library.

Popular feeling ran high, as is reflected in Isaac Reed's poem:

Many thousand human lives-

Butchered husbands, slaughtered wives

Mangled daughters, bleeding sons,

Hosts of martyred little ones,

(Worse than Herod's awful crime)

Sent to heaven before their time;

Lovers burnt and sweethearts drowned,

Darlings lost but never found!

All the horrors that hell could wish,

Such was the price that was paid for— fish!

Investigation of the cause of the 1889 dam breach and flood

On June 5, 1889, five days after the dam breach flood, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) appointed a committee of four prominent engineers to investigate the cause of the disaster. This committee was led by the esteemed James B. Francis, a hydraulic engineer best known for his work related to canals, flood control, turbine design, dam construction, and hydraulic calculations. Francis was a founding member of the ASCE and served as its president from November 1880 to January 1882. The ASCE committee visited the South Fork dam, reviewed the original engineering design of the dam and modifications made during repairs, interviewed eyewitnesses, commissioned a topographic survey of the dam remnants, and performed hydrologic calculations. In their final report they concluded the South Fork dam would have failed even if it had been maintained within the original design specifications, i.e., with a higher embankment crest and with five large discharge pipes at the dam's base. This claim by the ASCE committee has now been challenged.

The ASCE committee completed their investigation report on January 15, 1890, but the report was sealed and not shared with other ASCE members or the public. At ASCE's annual convention in June 1890, committee member Max Becker was quoted as saying “We will hardly report this session, unless pressed to do so, as we do not want to become involved in any litigation”. Although many ASCE members clamored for the report, it was not published in the society's transactions until two years after the disaster, in June 1891. William Shinn, a former managing partner with Andrew Carnegie, became the new President of ASCE in January, 1890. He gave the investigation report to outgoing President Becker to decide when to release it to the public. Becker kept it under wraps until the time of ASCE's convention in Chattanooga, TN, in 1891. The long-awaited report was presented at that meeting by James Francis. The other three investigators, William Worthen, Alphonse Fteley, and Max Becker, did not attend.

A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirms what had long been suspected, that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms. Lowering the dam by as much as 3 feet (0.91 m) and failing to replace the discharge pipes at the base of the dam cut in half the safe discharge capacity of the dam. This fatal lowering of the dam greatly reduced the capacity of the main spillway and virtually eliminated the action of an emergency spillway on the western abutment. Walter Frank first documented the presence of that emergency spillway in a 1988 ASCE publication. The existence of the emergency spillway is supported by topographic data from 1889 which shows the western abutment to be about one foot lower than the crest of the dam remnants, even after the dam had previously been lowered as much as 3 feet by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Adding the width of the emergency spillway to that of the main spillway yields the total width of spillway (wasteway) capacity that had been specified in the 1847 design of William Morris, a State Engineer.

Legacy and popular culture

At Point Park in Johnstown, at the confluence of the Stonycreek and Little Conemaugh rivers, an eternal flame burns in memory of the flood victims.

The Carnegie Library in Johnstown is now operated by the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, which has adapted it for use as the Johnstown Flood Museum.

Portions of the Stone Bridge have been made part of the Johnstown Flood National Memorial, established in 1969 and managed by the National Park Service.

The flood has been the subject or setting for numerous histories, novels, and other works as well.

Science fiction

- The Star Trek: The Original Series novel Rough Trails (2006) (third part of the Star Trek: New Earth mini-series) by L.A. Graf recreates the Johnstown Flood set on another planet.

- Peg Kehret's fantasy novel, The Flood Disaster, features two students assigned a project on the flood who travel back in time.

- Murray Leinster's fantasy novel The Time Tunnel (1967) features two time travelers who were unable to warn the Johnstown population of the coming disaster.

- Catherine Marshall's novel Julie features a teenage girl living in a small Pennsylvania town below an earthen dam in the 1930s; its events parallel the Johnstown Flood.

- Paul Mark Tag's science fiction novel Prophecy features the flood.

- Donald Keith's science fiction serial Mutiny in the Time Machine was published in Boys' Life magazine beginning in Dec 1962. It involved a Boy Scout troop discovering a time machine and travelling to Johnstown just prior to the flood.

- In the 1987–1996 animated Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles series, when New York City is flooded in the episode "20 000 Leaks Under the City", Burne Thompson says it is the biggest story since the Johnstown Flood.

Film and television

- The Johnstown Flood (1926 film) is a 1926 American silent epic film directed by Irving Cummings. A print is held at George Eastman House.

- The Johnstown Flood (1946 film), a 1946 animated film. Mighty Mouse uses time-reversal power to undo the flood and prevent the dam from breaking in the first place. One of a series of cartoons where he stops disasters that actually happened.

- Slap Shot (1977 film) was filmed in Johnstown, where the character played by Paul Newman refers to a statue of a dog that had warned the town of the coming flood.

- The Johnstown Flood (1989 film), a 1989 short documentary film which won the Best Documentary Academy Award in 1990.

- "Bloody Battles" episode of The Men Who Built America

Theater

- "A True History of the Johnstown Flood" by Rebecca Gilman

- By the early twentieth century, entertainers developed an exhibition portraying the flood, using moving scenery, light effects, and a live narrator. It was featured as a main attraction at the Stockholm Exhibition of 1909, where it was seen by 100,000 and presented as "our time's greatest electromechanical spectacle". The stage was 82 feet (25 m) wide, and the show employed a total of 13 stagehands.

Music

- "Mother Country", written by singer-songwriter John Stewart in 1969, contains the lyrics "What ever happened to those faces in the old photographs / I mean, the little boys....... / Boys? . . . . . Hell they were men / Who stood knee deep in the Johnstown mud / In the time of that terrible flood / And they listened to the water, that awful noise / And then they put away the dreams that belonged to little boys."

- "Highway Patrolman", a track from Bruce Springsteen's 1982 album Nebraska, mentions a fictional song titled "Night of the Johnstown Flood."

Literature

There is literature about the flood. Poems include:

- "The Pennsylvania Disaster", a poem by William McGonagall

- "By the Conemaugh", a poem by Florence Earle Coates

Short stories include:

- Brian Booker's "A Drowning Accident", in One Story (Issue #57, May 30, 2005), was largely based on the Johnstown Flood of 1889.

- Caitlín R. Kiernan featured the flood in her "To This Water (Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 1889)", in her collected Tales of Pain and Wonder (1994).

Books about the flood in a historical context include:

- Willis Fletcher Johnson wrote in 1889 a book called History of the Johnstown Flood (published by Edgewood Publishing Co.), likely the first book account of the flood.

- James Herbert Walker wrote the 1889 The Johnstown Horror or Valley of Death, published by National Publishing Company.

- Gertrude Quinn Slattery, who survived the flood as a six-year-old girl, published a memoir entitled Johnstown and Its Flood (1936).

- Historian and author David McCullough's first book was The Johnstown Flood (1968), published by Simon & Schuster.

- Weatherman and author Al Roker: Ruthless Tide. The Heroes and Villains of the Johnstown Flood, America's Astonishing Gilded Age Disaster. Audiobook released in 2018 by Harper Audio.

Fictional novels include:

- Rudyard Kipling noted the flood in his novel, Captains Courageous (1897), as the disaster that destroyed the family of the minor character "Pennsylvania Pratt."

- Marden A. Dahlstedt wrote the young adult novel, The Terrible Wave (1972), featuring a young girl as the main character, the book is inspired by the memoir of Gertrude Quinn (Slattery) who was six years old at the time of the flood.

- John Jakes featured the flood in his novel, The Americans (1979), set in 1890 and the final book in the series of The Kent Family Chronicles.

- Rosalyn Alsobrook wrote Emerald Storm (1985), a mass market historical romance set in Johnstown. The characters Patricia and Cole try to reunite with each other and loved ones after the flood.

- Kathleen Cambor wrote the historical novel In Sunlight, In a Beautiful Garden (2001), based on events of the flood. The book was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

- Richard A. Gregory wrote The Bosses Club, The conspiracy that caused the Johnstown Flood, destroying the iron and steel capital of America (2011), a historical novel that proposes a theory of the involvement of Andrew Carnegie and other wealthy American industrialists in the Johnstown Flood, told through the lives of two survivors.

- Catherine Marshall wrote "Julie" (1984) which describes the concerns leading up to the failing dam and the days before, during and after the flood itself from the perspective of an 18 year old girl who works at a newspaper and tries with her father to warn the town.

- Judith Redline Coopey wrote Waterproof: A Novel of the Johnstown Flood (2012), a story of Pamela Gwynedd McCrae from 1889–1939 through flashbacks.

- Kathleen Danielczyk wrote "Summer of Gold and Water" (2013) which tells story of life at the lake, the flood and a coming together of the classes.

- Colleen Coble wrote "The Wedding Quilt Bride" (2001) which tells the story of a romance between a member of the club's granddaughter and a man brought in to see if the dam was really in trouble. It follows him trying to convince the people of the danger and then the flood.

- Michael Stephan Oates wrote the historical fiction novel "Wade in the Water" (2014), a coming of age tale set against the backdrop of the Johnstown flood.

- Jeanette Watts's "Wealth and Privilege" (2014) portrays the Fishing and Hunting Club at its heyday, and then the main characters scramble for their lives in the Flood at the novel's climax.

- Mary Hogan's "The Woman In the Photo" (2016) writes about two young women in present-day and Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1889.

- Jane Claypool Miner wrote "Jennie" (1989). An historical fiction romance written about a young girl who rides the flood from South Fork to Johnstown and survives. She then works as a telegraph operator for the reporters flooding the town while advocating for the people living there.

Humor as a speaker's resource:

- Variations on story of an elderly man lived through the Johnstown Flood (or in Johnstown PA) and bored countless of his contemporaries with his narratives about the Johnstown Flood. When he died, he went to Heaven and was greeted by St. Peter, whom he told that he wanted to tell the gripping story one more time. He's permitted to retell the story but warned that Noah will be in the crowd or audience.

See also

- Austin, Pennsylvania Dam Failure

- St. Francis Dam disaster

- Vajont Dam disaster

References

- ^ "Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 1904". Library of Congress. World Digital Library. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ McCullough, David (1968). The Johnstown Flood. ISBN 978-0-671-20714-4.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Coleman, Neil M.; Kaktins, Uldis; Wojno, Stephanie (2016). "Dam-Breach hydrology of the Johnstown flood of 1889–challenging the findings of the 1891 investigation report". Heliyon. 2 (6): e00120. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00120. PMC 4946313. PMID 27441292.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sid Perkins, "Johnstown Flood matched volume of Mississippi River", Science News, Vol.176 #11, 21 November 2009, accessed 14 October 2012

- Gibson, Christine. "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters". American Heritage (August/September 2006). Archived from the original on December 5, 2010.

- "Founder Clara Barton". The American National Red Cross. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Johnstown Flood of 1889 – Historic". Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "The Johnstown Flood Of 1889", The Weather Channel Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frank, Walter Smoter (2004). "The Cause of the Johnstown Flood". Walter Smoter Frank. Civil Engineering, pp. 63–66, May 1988

- "The South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club and the South Fork Dam", Johnstown Flood Museum Archived 2013-11-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Coleman, Neil (2018). Johnstown's Flood of 1889 - Power over Truth and the Science Behind the Disaster. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-319-95215-4.

- Lane, F.W. The Elements Rage (David & Charles 1966), p.129

- Kaktins, Uldis, Davis Todd, C., Wojno, S., Coleman, N.M. (2013). Revisiting the timing and events leading to and causing the Johnstown Flood of 1889. Pennsylvania History, v. 80, no. 3, 335–363.

- JAHA "Johnstown Flood Museum: Pennsylvania Railroad Interview Transcripts" Archived 2013-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- History of the Johnstown Flood, Willis Fletcher Johnson (1889), pp 61–64. Available on CD-ROM from "Johnstown" Archived 2006-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, Between the Lakes

- Lane, F.W. The Elements Rage (David & Charles 1966), p.131

- ^ "Statistics about the great disaster", Johnstown Flood Museum,The Johnstown Area Heritage Association. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Pace, Eric (March 24, 1997). "Frank Shomo, Infant Survivor Of Johnstown Flood, Dies at 108". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ""The Johnstown Flood", by Robert D. Christie, The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Volume 54, Number 2, April 1971". Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "May 31, 1889 CE: Johnstown Flood", National Geographic. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Zebrowski, Ernest (1998). Perils of a Restless Planet: Scientific Perspectives on Natural Disasters. Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780521654883.

- https://archive.org/stream/StillCastingShadowsASharedMosaicOfU.s.HistoryVol.I1620-1914/StillCastingShadows1_djvu.txt (in which, text-search for text "Mining a similar vein")

- ^ Francis, J.B.; Worthen, W.E.; Becker, M.J.; Fteley, A. (1891). "Report of the Committee on the Cause of the Failure of the South Fork Dam". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. v. XXIV: 431–469.

- ^ Coleman, Neil M.; Wojno, Stephanie; Kaktins, Uldis (2017). "The Johnstown Flood of 1889 – Challenging the Findings of the ASCE Investigation Report". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 49 (2). Paper No. 29-10. doi:10.1130/abs/2017NE-290358.

- Coleman, Neil (2018). Johnstown's Flood of 1889 - Power Over Truth and the Science Behind the Disaster. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 89. ISBN 978-3-319-95215-4.

- "Johnstown Flood Museum". Johnstown Area Heritage Association. 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Ayers, Jeff (2006). Voyages of Imagination. Pocket Books. pp. 431–432. ISBN 978-1-4165-0349-1.

- Inc, Boy Scouts of America (1 December 1962). "Boys' Life". Boy Scouts of America, Inc.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "20 000 Leaks Under the City". Allreadable. 1989. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Silent Era : Progressive Silent Film List". Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "Theater Loop – Chicago Theater News & Reviews – Chicago Tribune". Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Shelley Johansson of the Johnstown Flood Museum, "First Person: The Swedish Johnstown flood", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 30 July 2011

- "Johnstowns undergång", Hvar 8 dag, issue 41, 11 July 1909, at Runeberg website

- McGonagall, William (1889). "The Pennsylvania Disaster". McGonagall Online.

- "One Story". Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Wescott, David (6 December 2013). "Teaching flood preparedness to Noah". It's Not a Lecture.

Bibliography

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Johnstown" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 475.

- Coleman, Neil M. Johnstown's Flood of 1889 - Power Over Truth and the Science Behind the Disaster (2018). Springer International Publishing AG. 256 pp. 978-3-319-95215-4 978-3-319-95216-1 (eBook)

- Coleman, Neil M., Wojno, Stephanie, and Kaktins, Uldis. (2017). The Johnstown Flood of 1889 – Challenging the Findings of the ASCE Investigation Report. Paper No. 29-10. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Vol. 49, No. 2. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2017NE/webprogram/Paper290358.html. doi: 10.1130/abs/2017NE-290358.

- Coleman, Neil M., Kaktins, Uldis, and Wojno, Stephanie (2016). Dam-Breach hydrology of the Johnstown flood of 1889 – challenging the findings of the 1891 investigation report, Heliyon, https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00120.

- Coleman, Neil M., Wojno, Stephanie, and Kaktins, Uldis. (2016). Dam-breach hydrology of the Johnstown Flood of 1889 – Challenging the findings of the 1891 investigation report. Paper No. 178-5. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Vol. 48, No. 7. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2016AM/webprogram/Paper283665.html. doi: 10.1130/abs/2016AM-283665.

- Coleman, Neil M., Davis Todd, C., Myers, Reed A., Kaktins, Uldis (2009). "Johnstown flood of 1889 – destruction and rebirth" (Presentation 76-9). Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 41, No. 7, p. 216.

- Davis T., C., Coleman, Neil M., Meyers, Reed A., and Kaktins, Uldis (2009). A determination of peak discharge rate and water volume from the 1889 Johnstown Flood (Presentation 76-10). Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 41, No. 7, p. 216.

- Kaktins, Uldis, Davis Todd, C., Wojno, S., Coleman, N.M. (2013). Revisiting the timing and events leading to and causing the Johnstown Flood of 1889. Pennsylvania History, v. 80, no. 3, 335–363.

- Johnson, Willis Fletcher. History of the Johnstown Flood (1889).

- McCullough, David. The Johnstown Flood (1968); ISBN 0-671-20714-8

- O'Connor, R. Johnstown – The Day The Dam Broke (1957).

External links

- "Johnstown Flood Memorial", National Park Service

- Johnstown Flood Museum – Johnstown Area Heritage Association

- A Valley of Death Three Rivers Tribune (Three Rivers Michigan) #45 Vol. XI June 7, 1889

- Benefit event for Johnstown Flood Sufferers held on June 14, 1889

- "The Johnstown Flood", Greater Johnstown/Cambria County Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Ernest Zebrowski (1999). Perils of a Restless Planet: Scientific Perspectives on Natural Disasters. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65488-3.

- Google Earth view showing Johnstown and the South Fork Dam site

- "Johnstown Flood', by Jeffrey J. Kitsko, Pennsylvania Highways, January 27, 2015.

- "'It's still controversial': Debate rages over culpability of wealthy club members" by David Hurst The Tribune-Democrat, May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

40°20′25″N 78°46′15″W / 40.34028°N 78.77083°W / 40.34028; -78.77083

| City of Johnstown | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Metro area | |||

| History/attractions | |||

| Transportation | |||

| Education | |||

| Industry | |||

| Entertainment/sports | |||

| Media/pop culture | |||

| Television |

| ||

| Radio | |||