| Revision as of 15:17, 4 January 2022 editBrownHairedGirl (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers2,942,733 editsm some ref cleanup tags should be AFTER </ref>, replaced: {{self-published inline|expert=yes|date=December 2017}}</ref> → </ref>{{self-published inline|expert=yes|date=December 2017}}Tag: AWB← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:43, 28 January 2022 edit undoGeysirhead (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users19,458 edits removed Category:Pejorative terms for people; added Category:Ethnic and religious slurs using HotCatNext edit → | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 18:43, 28 January 2022

Pejorative term for an Irish person who admires British customs

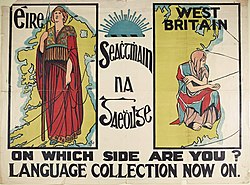

West Brit, an abbreviation of West Briton, is a derogatory term for an Irish person who is perceived as Anglophilic in matters of culture or politics. West Britain is a description of Ireland emphasising it as under British influence.

History

"West Britain" was used with reference to the Acts of Union 1800 which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Similarly "North Britain" for Scotland used after the 1603 Union of the Crowns and the Acts of Union 1707 connected it to the Kingdom of England ("South Britain"). In 1800 Thomas Grady, a Limerick unionist, published a collection of light verse called The West Briton, while an anti-union cartoon depicted an official offering bribes and proclaiming "God save the King & his Majesty's subjects of west Britain that is to be!" In 1801 the Latin description of George III on the Great Seal of the Realm was changed from MAGNÆ BRITANNIÆ FRANCIÆ ET HIBERNIÆ REX "King of Great Britain, France and Ireland" to BRITANNIARUM REX "King of the Britains", dropping the claim to the French throne and describing Great Britain and Ireland as "the Britains".

Irish unionist MP Thomas Spring Rice (later Lord Monteagle of Brandon) said on 23 April 1834 in the House of Commons in opposing Daniel O'Connell's motion for Repeal of the Union, "I should prefer the name of West Britain to that of Ireland". Rice was derided by Henry Grattan later in the same debate: "He tells us, that he belongs to England, and designates himself as a West Briton." Daniel O'Connell himself used the phrase at a pro-Repeal speech in Dublin in February 1836:

The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons, if made so in benefits and justice; but if not, we are Irishmen again.

Here, O'Connell was hoping that Ireland would soon become as prosperous as "North Britain" had become after 1707, but if the Union did not deliver this, then some form of Irish home rule was essential. The Dublin administration as conducted in the 1830s was, by implication, an unsatisfactory halfway house between these two ideals, and as a prosperous "West Britain" was unlikely, home rule was the rational best outcome for Ireland.

"West Briton" next came to prominence in a pejorative sense during the land struggle of the 1880s. D. P. Moran, who founded The Leader in 1900, used the term frequently to describe those who he did not consider sufficiently Irish. It was synonymous with those he described as "Sourfaces", who had mourned the death of the Queen Victoria in 1901. It included virtually all Church of Ireland Protestants and those Catholics who did not measure up to his definition of "Irish Irelanders".

In 1907, Canon R. S. Ross-Lewin published a collection of loyal Irish poems under the pseudonym "A County of Clare West Briton", explaining the epithet in the foreword:

Now, what is the exact definition and up-to-date meaning of that term? The holder of the title may be descended from O'Connors and O'Donelans and ancient Irish Kings. He may have the greatest love for his native land, desirous to learn the Irish language, and under certain conditions to join the Gaelic League. He may be all this, and rejoice in the victory of an Irish horse in the "Grand National", or an Irish dog at "Waterloo", or an Irish tug-of-war team of R.I.C. giants at Glasgow or Liverpool, but, if he does not at the same time hate the mere Saxon, and revel in the oft resuscitated pictures of long past periods, and the horrors of the penal laws he is a mere "West Briton", his Irish blood, his Irish sympathies go for nothing. He misses the chief qualifications to the ranks of the "Irish best", if he remains an imperialist, and sees no prospect of peace or happiness or return of prosperity in the event of the Union being severed. In this sense, Lord Roberts, Lord Charles Beresford and hundreds of others, of whom all Irishmen ought to be proud, are "West Britons", and thousands who have done nothing for the empire, under the just laws of which they live, who, perhaps, are mere descendants of Cromwell's soldiers, and even of Saxon lineage, with very little Celtic blood in their veins, are of the "Irish best".

Ernest Augustus Boyd's 1924 collection Portraits: real and imaginary included "A West Briton", which gave a table of West-Briton responses to keywords:

Word Response Sinn Féin Pro-German Irish Vulgar England Mother-country Green Red Nationality Disloyalty Patriotism O.B.E. Self-determination Czecho-Slovakia

According to Boyd, "The West Briton is the near Englishman ... an unfriendly caricature, the reductio ad absurdum of the least attractive English characteristics. ... The best that can be said ... is that the species is slowly becoming extinct. ... nationalism has become respectable". The opposite of the "West Briton" Boyd called the "synthetic Gael".

After the independence of the Irish Free State, "West British" was applied mainly to anglophile Roman Catholics, the small number of Catholic unionists, as Protestants were expected to be naturally unionists. This was not automatic, since there were, and are, also Anglo-Irish Protestants favouring Irish republicanism (see Protestant Irish nationalism).

Contemporary usage

"Brit" meaning "British person", attested in 1884, is pejorative in Irish usage, though used as a value-neutral colloquialism in Great Britain. During the Troubles, among nationalists "the Brits" specifically meant the British Army in Northern Ireland. "West Brit" is today used by Irish people, chiefly within Ireland, to criticise a variety of perceived faults of other Irish people:

- "Revisionism" (compare historical revisionism and historical negationism):

- Criticism of historical Irish uprisings. (State policy is to praise the patriotism of rebels up to the revolutionary period, while condemning later physical force republicans as antidemocratic.)

- highlighting perceived benefits of British rule in Ireland

- downplaying British actions during historical events in Ireland such as the Great Famine

- Antipathy to Irish rebel songs.

- Anglophilia: following British popular culture; admiration for the British royal family; support for the Republic of Ireland rejoining the Commonwealth of Nations or becoming a Commonwealth Realm; highlighting positive British influence in the world, past or present

- Cultural cringe: appearing embarrassed by or disdainful of aspects of Irish culture, such as the Irish language, Hiberno-English, Gaelic games, or Irish traditional music

- Partitionism: Opposition or indifference to a United Ireland; showing political support for neo-unionism

Not all people so labelled may actually be characterised by these stereotypical views and habits.

Public perception and self-identity can vary. During his 2011 presidential campaign, Sinn Féin candidate Martin McGuinness criticised what he called West Brit elements of the media, who he said were out to undermine his attempt to win the election. He later said it was an "off-the-cuff remark" but did not define for the electorate what (or who) he had meant by the term.

Irish entertainer Terry Wogan, who spent most of his career working for the BBC in Britain, described himself as a West Brit: "I'm an effete, urban Irishman. I was an avid radio listener as a boy, but it was the BBC, not RTÉ. I was a West Brit from the start. I'm a kind of child of the Pale. I think I was born to succeed here ; I have much more freedom than I had in Ireland." He became a dual citizen of Ireland and the UK and was eventually knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

The Irish Times columnist Donald Clarke noted a number of things that may prompt the application of a West Brit label, including being from Dublin (or south Dublin), supporting UK-based football teams, using the phrase "Boxing Day", or voting for Fine Gael.

Similar terms

Castle Catholic was applied more specifically by Republicans to middle-class Catholics assimilated into the pro-British establishment, after Dublin Castle, the centre of the British administration. Sometimes the exaggerated pronunciation spelling Cawtholic was used to suggest an accent imitative of British Received Pronunciation.

These identified Catholic unionists whose involvement in the British system was the whole aim of O'Connell's Emancipation Act of 1829. Having and exercising their new legal rights under the Act, Castle Catholics were then rather illogically being pilloried by other Catholics for exercising them to the full.

The old-fashioned word shoneen (from Irish: Seoinín, diminutive of Seán, thus literally 'Little John', and apparently a reference to John Bull) was applied to those who emulated the homes, habits, lifestyle, pastimes, clothes, and zeitgeist of the Protestant Ascendancy. P. W. Joyce's English As We Speak It in Ireland defines it as "a gentleman in a small way: a would-be gentleman who puts on superior airs." A variant since c. 1840, jackeen ('Little Jack'), was used in the countryside in reference to Dubliners with British sympathies; it is a pun, substituting the nickname Jack for John, as a reference to the Union Jack, the British flag. In the 20th century, jackeen took on the more generalized meaning of "a self-assertive worthless fellow".

Antonyms

The term is sometimes contrasted with Little Irelander, a derogatory term for an Irish person who is seen as excessively nationalistic, Anglophobic and xenophobic, sometimes also practising a strongly conservative form of Roman Catholicism. This term was popularised by Seán Ó Faoláin. "Little Englander" had been an equivalent term in British politics since about 1859.

An antonym of jackeen, in its modern sense of an urban (and strongly British-influenced) Dubliner, is culchie, referring to an unsophisticated Irish person who resides in the countryside.

See also

References

- Quinion, Michael (10 March 2004). "West Brit". World Wide Words. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "All kinds of things can get you called a West Brit these days". The Irish Times. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- McNamee, Michael Sheils (28 November 2019). "Would you take offence at being called a West Brit? The term has a muddled history". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Reilly, Gavan (28 November 2019). "McGuinness blames 'West Brit' influence for references to IRA past". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Grady, Thomas (1800). The West Briton: Being a collection of poems, on various subjects. Dublin: Printed by Graisberry and Campbell for Bernard Dornin. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Barrington, Jonah (1844). "Ch. XXIV". Historic Records and Secret Memoirs of the Legislative Union Between Great Britain and Ireland. London: Colburn. p. 385. Retrieved 8 February 2016 – via Google Books.

- Geoghegan, Patrick M. (2000). "'An Act of Power & Corruption'? The Union Debate". History Ireland. 8 (2): 22–26: 25. ISSN 0791-8224. JSTOR 27724771.

- Hourican, Bridget. "Rice, Thomas Spring". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Repeal of the Union—Adjourned Debate". Hansard House of Commons Debate. 23 April 1834. Col. 1194. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Repeal of the Union—Adjourned Debate—Fourth Day". Hansard: House of Common Debate. 25 April 1834. Col. 57. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Fagan, William (1847). The Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell. Vol. II. Cork: J. O'Brien. p. 496.

- ^ "D.P. Moran and the leader: Writing an Irish Ireland through partition". Eire–Ireland: Journal of Irish Studies. 2003. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Ross-Lewin, R. S. (1907). "Preface". Poems. Limerick: McKern. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Boyd, Ernest Augustus (1970) . "A West Briton". Portraits: real and imaginary, being memories and impressions of friends and contemporaries; with appreciations of divers singularities and characteristics of certain phases of life and letters among the North Americans as seen, heard, and divined. New York: George H. Doran. pp. 140–145. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Definition of Brit". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- McArthur, Tom (17 October 2008). "An ABC of World English Brit to Creole". English Today. 1 (2): 21–27. doi:10.1017/S0266078400000122.

- Wall, Richard (2000). "Intra-lingual translation: Irish English–standard English" (PDF). Bells: Barcelona English Language and Literature Studies. 11: 249–256: 254.

- "McGuinness blames 'West Brit' influence for references to IRA past". The Journal. 11 September 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- McKittrick, David (21 September 2011). "McGuinness launches attack on media". The Independent. London. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Martin McGuinness backtracks after 'west Brit' jibe". The Belfast Telegraph. 21 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "McGuinness declines to define 'West Brit'". Irish Examiner. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "Terry Wogan interview: 'I'm a child of the Pale. I think I was born to succeed here'". Irish Times. 31 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "All kinds of things can get you called a West Brit these days". 12 January 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Fine Gael is still haunted by 'West-British' moniker - despite its role in republic". independent.ie. Independent News& Media. 14 April 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Joyce, P. W. English As We Speak It in Ireland: Rabble to Yoke. p. 321.

- Simpson, John; Weiner, Edmund, eds. (1989). "jackeen". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bonaccorso, Richard (1987). Sean O'Faolain's Irish Vision. SUNY Press. p. 29.

- p. 676 Ashman, Patricia Little Englanders in Historical Dictionary of the British Empire, Volume 2 edited by James Stuart Olson and Robert Shadle Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996

- Dolan, Terence Patrick (2006). A Dictionary of Hiberno-English. Cork: Gill & Macmillan. p. 70. ISBN 9780717140398.