| Revision as of 06:19, 2 August 2022 editWhywhenwhohow (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers49,153 edits Rescuing 13 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.8.9Tag: IABotManagementConsole [1.2]← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:16, 10 August 2022 edit undoJettlax (talk | contribs)20 edits →Adverse effectsTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

| Common side effects include ], ], ], trouble seeing, constipation, and increased weight.<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Has2012/> About 9 to 20% of people gained more than 7% of the baseline weight depending on the dose.<ref name=AHFS2015/> Serious side effects may include the potentially permanent movement disorder ], as well as ], an increased risk of ], and ].<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Ric2015/> In older people with ] as a result of dementia, it may increase the risk of death.<ref name=AHFS2015/> | Common side effects include ], ], ], trouble seeing, constipation, and increased weight.<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Has2012/> About 9 to 20% of people gained more than 7% of the baseline weight depending on the dose.<ref name=AHFS2015/> Serious side effects may include the potentially permanent movement disorder ], as well as ], an increased risk of ], and ].<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name=Ric2015/> In older people with ] as a result of dementia, it may increase the risk of death.<ref name=AHFS2015/> | ||

| While atypical antipsychotics appear to have a lower rate of movement problems as compared to typical antipsychotics, risperidone has a high risk of movement problems among the atypicals.<ref name=Div2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N | title = Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects | journal = BioMed Research International | volume = 2014 | pages = 656370 | date = 2014 | pmid = 24995318 | pmc = 4065707 | doi = 10.1155/2014/656370 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name=Pil2017>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pillay J, Boylan K, Carrey N, Newton A, Vandermeer B, Nuspl M, MacGregor T, Jafri SH, Featherstone R, Hartling L | title = First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Children and Young Adults: Systematic Review Update | journal = Comparative Effectiveness Reviews | issue = 184 | pages = ES–24 | date = March 2017 | pmid = 28749632 | quote = Compared with FGAs, SGAs may decrease the risk for experiencing any extrapyramidal symptom (EPS). FGAs probably cause lower gains in weight and BMI. | id = Report 17-EHC001-EF. Bookshelf ID: NBK442352 }}</ref> |

While atypical antipsychotics appear to have a lower rate of movement problems as compared to typical antipsychotics, risperidone has a high risk of movement problems among the atypicals.<ref name=Div2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N | title = Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects | journal = BioMed Research International | volume = 2014 | pages = 656370 | date = 2014 | pmid = 24995318 | pmc = 4065707 | doi = 10.1155/2014/656370 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name=Pil2017>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pillay J, Boylan K, Carrey N, Newton A, Vandermeer B, Nuspl M, MacGregor T, Jafri SH, Featherstone R, Hartling L | title = First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Children and Young Adults: Systematic Review Update | journal = Comparative Effectiveness Reviews | issue = 184 | pages = ES–24 | date = March 2017 | pmid = 28749632 | quote = Compared with FGAs, SGAs may decrease the risk for experiencing any extrapyramidal symptom (EPS). FGAs probably cause lower gains in weight and BMI. | id = Report 17-EHC001-EF. Bookshelf ID: NBK442352 }}</ref> Most atypical antipsychotics, however, are associated with a greater amount of weight gain and other metabolic side effects.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pillinger |first=Toby |last2=McCutcheon |first2=Robert A |last3=Vano |first3=Luke |last4=Mizuno |first4=Yuya |last5=Arumuham |first5=Atheeshaan |last6=Hindley |first6=Guy |last7=Beck |first7=Katherine |last8=Natesan |first8=Sridhar |last9=Efthimiou |first9=Orestis |last10=Cipriani |first10=Andrea |last11=Howes |first11=Oliver D |date=2020-01 |title=Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S221503661930416X |journal=The Lancet Psychiatry |language=en |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=64–77 |doi=10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30416-X |pmc=PMC7029416 |pmid=31860457}}</ref><ref name=Pil2017/> | ||

| ===Drug interactions=== | ===Drug interactions=== | ||

Revision as of 04:16, 10 August 2022

Atypical antipsychotic medicationPharmaceutical compound

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Risperdal, Okedi, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a694015 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular, subcutaneous |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70% (by mouth) |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6 mediated to 9-hydroxyrisperidone) |

| Elimination half-life | 20 hours (by mouth), 3–6 days (IM) |

| Excretion | Urinary (70%) feces (14%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| PubChem SID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.114.705 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

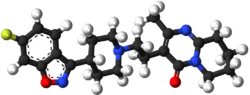

| Formula | C23H27FN4O2 |

| Molar mass | 410.493 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Risperidone, sold under the brand name Risperdal among others, is an atypical antipsychotic used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is taken either by mouth or by injection (subcutaneous or intramuscular). The injectable versions are long-acting and last for 2-4 weeks.

Common side effects include movement problems, sleepiness, dizziness, trouble seeing, constipation, and increased weight. Serious side effects may include the potentially permanent movement disorder tardive dyskinesia, as well as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, an increased risk of suicide, and high blood sugar levels. In older people with psychosis as a result of dementia, it may increase the risk of death. It is unknown if it is safe for use in pregnancy. Its mechanism of action is not entirely clear, but is believed to be related to its action as a dopamine and serotonin antagonist.

Study of risperidone began in the late 1980s and it was approved for sale in the United States in 1993. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is available as a generic medication. In 2019, it was the 149th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 4 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

Risperidone is mainly used for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and irritability associated with autism.

Schizophrenia

Risperidone is effective in treating psychogenic polydipsia and the acute exacerbations of schizophrenia.

Studies evaluating the utility of risperidone by mouth for maintenance therapy have reached varying conclusions. A 2012 systematic review concluded that evidence is strong that risperidone is more effective than all first-generation antipsychotics other than haloperidol, but that evidence directly supporting its superiority to placebo is equivocal. A 2011 review concluded that risperidone is more effective in relapse prevention than other first- and second-generation antipsychotics with the exception of olanzapine and clozapine. A 2016 Cochrane review suggests that risperidone reduces the overall symptoms of schizophrenia, but firm conclusions are difficult to make due to very low-quality evidence. Data and information are scarce, poorly reported, and probably biased in favour of risperidone, with about half of the included trials developed by drug companies. The article raises concerns regarding the serious side effects of risperidone, such as parkinsonism. A 2011 Cochrane review compared risperidone with other atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine for schizophrenia:

| Summary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone seems to produce somewhat more extrapyramidal side effects and clearly more prolactin increase than most other atypical antipsychotics. It may also differ from other compounds in the occurrence of other adverse effects such as weight gain, metabolic problems, cardiac effects, sedation, and seizures. Nevertheless, the large proportion of participants leaving studies early and incomplete reporting of outcomes makes drawing firm conclusions difficult. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Long-acting injectable formulations of antipsychotic drugs provide improved compliance with therapy and reduce relapse rates relative to oral formulations. The efficacy of risperidone long-acting injection appears to be similar to that of long acting injectable forms of first generation antipsychotics.

Bipolar disorder

Second-generation antipsychotics, including risperidone, are effective in the treatment of manic symptoms in acute manic or mixed exacerbations of bipolar disorder. In children and adolescents, risperidone may be more effective than lithium or divalproex, but has more metabolic side effects. As maintenance therapy, long-acting injectable risperidone is effective for the prevention of manic episodes but not depressive episodes. The long-acting injectable form of risperidone may be advantageous over long acting first generation antipsychotics, as it is better tolerated (fewer extrapyramidal effects) and because long acting injectable formulations of first generation antipsychotics may increase the risk of depression.

Autism

Compared to placebo, risperidone treatment reduces certain problematic behaviors in autistic children, including aggression toward others, self-injury, challenging behaviour, and rapid mood changes. The evidence for its efficacy appears to be greater than that for alternative pharmacological treatments. Weight gain is an important adverse effect. Some authors recommend limiting the use of risperidone and aripiprazole to those with the most challenging behavioral disturbances in order to minimize the risk of drug-induced adverse effects. Evidence for the efficacy of risperidone in autistic adolescents and young adults is less persuasive.

Dementia

While antipsychotic medications such as risperidone have a slight benefit in people with dementia, they have been linked to higher incidence of death and stroke. Because of this increased risk of death, treatment of dementia-related psychosis with risperidone is not FDA approved and carries a black box warning. However many other jurisdictions regularly use it to control severe aggression and psychosis in those with dementia when other non-pharmacological interventions have failed and their pharmaceutical regulators have approved its use in this population.

Other uses

Risperidone has shown promise in treating therapy-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder, when serotonin reuptake inhibitors alone are not sufficient.

Risperidone has not demonstrated a benefit in the treatment of eating disorders or personality disorders, except for limited evidence in schizotypal personality disorder.

Forms

Available forms of risperidone include tablet, oral dissolving tablet, oral solution, and powder and solvent for suspension for injection.

Adverse effects

See also: List of adverse effects of risperidoneCommon side effects include movement problems, sleepiness, dizziness, trouble seeing, constipation, and increased weight. About 9 to 20% of people gained more than 7% of the baseline weight depending on the dose. Serious side effects may include the potentially permanent movement disorder tardive dyskinesia, as well as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, an increased risk of suicide, and high blood sugar levels. In older people with psychosis as a result of dementia, it may increase the risk of death.

While atypical antipsychotics appear to have a lower rate of movement problems as compared to typical antipsychotics, risperidone has a high risk of movement problems among the atypicals. Most atypical antipsychotics, however, are associated with a greater amount of weight gain and other metabolic side effects.

Drug interactions

- Carbamazepine and other enzyme inducers may reduce plasma levels of risperidone. If a person is taking both carbamazepine and risperidone, the dose of risperidone will likely need to be increased. The new dose should not be more than twice the patient's original dose.

- CYP2D6 inhibitors, such as SSRI medications, may increase plasma levels of risperidone and those medications.

- Since risperidone can cause hypotension, its use should be monitored closely when a patient is also taking antihypertensive medicines to avoid severe low blood pressure.

- Risperidone and its metabolite paliperidone are reduced in efficacy by P-glycoprotein inducers such as St John's wort

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse. Some have argued the additional somatic and psychiatric symptoms associated with dopaminergic super-sensitivity, including dyskinesia and acute psychosis, are common features of withdrawal in individuals treated with neuroleptics. This has led some to suggest the withdrawal process might itself be schizomimetic, producing schizophrenia-like symptoms even in previously healthy patients, indicating a possible pharmacological origin of mental illness in a yet unknown percentage of patients currently and previously treated with antipsychotics. This question is unresolved, and remains a highly controversial issue among professionals in the medical and mental health communities, as well as the public.

Dementia

Older people with dementia-related psychosis are at a higher risk of death if they take risperidone compared to those who do not. Most deaths are related to heart problems or infections.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

See also: Atypical antipsychotic § Pharmacodynamics, and Antipsychotic § Comparison of medications| Site | Ki (nM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 423 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT1B | 14.9 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT1D | 84.6 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2A | 0.17 | Inverse agonist |

| 5-HT2B | 61.9 | Inverse agonist |

| 5-HT2C | 12.0 | Inverse agonist |

| 5-HT5A | 206 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT6 | 2,060 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT7 | 6.60 | Irreversible antagonist |

| α1A | 5.0 | Antagonist |

| α1B | 9.0 | Antagonist |

| α2A | 16.5 | Antagonist |

| α2B | 108 | Antagonist |

| α2C | 1.30 | Antagonist |

| D1 | 244 | Antagonist |

| D2 | 3.57 | Antagonist |

| D2S | 4.73 | Antagonist |

| D2L | 4.16 | Antagonist |

| D3 | 3.6 | Inverse agonist |

| D4 | 4.66 | Antagonist |

| D5 | 290 | Antagonist |

| H1 | 20.1 | Inverse agonist |

| H2 | 120 | Inverse agonist |

| mAChTooltip Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor | >10,000 | Negligible |

Risperidone has been classified as a "qualitatively atypical" antipsychotic agent with a relatively low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects (when given at low doses) that has more pronounced serotonin antagonism than dopamine antagonism. Risperidone contains the functional groups of benzisoxazole and piperidine as part of its molecular structure. Although not a butyrophenone, it was developed with the structures of benperidol and ketanserin as a basis. It has actions at several 5-HT (serotonin) receptor subtypes. These are 5-HT2C, linked to weight gain, 5-HT2A, linked to its antipsychotic action and relief of some of the extrapyramidal side effects experienced with the typical neuroleptics.

It has been found that D-amino acid oxidase, the enzyme that catalyses the breakdown of D-amino acids (e.g. D-alanine and D-serine — the neurotransmitters) is inhibited by risperidone.

Risperidone acts on the following receptors:

Dopamine receptors: This drug is an antagonist of the D1 (D1, and D5) as well as the D2 family (D2, D3 and D4) receptors, with 70-fold selectivity for the D2 family. It has "tight binding" properties, which means it has a long half-life. Like other antipsychotics, risperidone blocks the mesolimbic pathway, the prefrontal cortex limbic pathway, and the tuberoinfundibular pathway in the central nervous system. Risperidone may induce extrapyramidal side effects, akathisia and tremors, associated with diminished dopaminergic activity in the striatum. It can also cause sexual side effects, galactorrhoea, infertility, gynecomastia and, with chronic use reduced bone mineral density leading to breaks, all of which are associated with increased prolactin secretion.

Serotonin receptors: Its action at these receptors results in a relatively lesser tendency to cause extrapyramidal side effects, like the reference substance clozapine.

Alpha α1 adrenergic receptors: This action accounts for the orthostatic hypotensive effects and perhaps some of the sedating effects of risperidone.

Alpha α2 adrenergic receptors: Risperidone's action at these receptors may cause greater positive, negative, affective, and cognitive symptom control.

Histamine H1 receptors: effects on these receptors account for its sedation and reduction in vigilance. This may also lead to drowsiness and weight gain.

Voltage-gated sodium channels: Because it accumulates in synaptic vesicles, Risperidone inhibits voltage-gated sodium channels at clinically used concentrations.

Pharmacokinetics

Risperidone undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion. Lower doses are recommended for patients with severe liver and kidney disease. The active metabolite of risperidone, paliperidone, is also used as an antipsychotic.

| Medication | Brand name | Class | Vehicle | Dosage | Tmax | t1/2 single | t1/2 multiple | logP | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole lauroxil | Aristada | Atypical | Water | 441–1064 mg/4–8 weeks | 24–35 days | ? | 54–57 days | 7.9–10.0 | |

| Aripiprazole monohydrate | Abilify Maintena | Atypical | Water | 300–400 mg/4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30–47 days | 4.9–5.2 | |

| Bromperidol decanoate | Impromen Decanoas | Typical | Sesame oil | 40–300 mg/4 weeks | 3–9 days | ? | 21–25 days | 7.9 | |

| Clopentixol decanoate | Sordinol Depot | Typical | Viscoleo | 50–600 mg/1–4 weeks | 4–7 days | ? | 19 days | 9.0 | |

| Flupentixol decanoate | Depixol | Typical | Viscoleo | 10–200 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–10 days | 8 days | 17 days | 7.2–9.2 | |

| Fluphenazine decanoate | Prolixin Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/2–5 weeks | 1–2 days | 1–10 days | 14–100 days | 7.2–9.0 | |

| Fluphenazine enanthate | Prolixin Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/1–4 weeks | 2–3 days | 4 days | ? | 6.4–7.4 | |

| Fluspirilene | Imap, Redeptin | Typical | Water | 2–12 mg/1 week | 1–8 days | 7 days | ? | 5.2–5.8 | |

| Haloperidol decanoate | Haldol Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 20–400 mg/2–4 weeks | 3–9 days | 18–21 days | 7.2–7.9 | ||

| Olanzapine pamoate | Zyprexa Relprevv | Atypical | Water | 150–405 mg/2–4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30 days | – | |

| Oxyprothepin decanoate | Meclopin | Typical | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 8.5–8.7 | |

| Paliperidone palmitate | Invega Sustenna | Atypical | Water | 39–819 mg/4–12 weeks | 13–33 days | 25–139 days | ? | 8.1–10.1 | |

| Perphenazine decanoate | Trilafon Dekanoat | Typical | Sesame oil | 50–200 mg/2–4 weeks | ? | ? | 27 days | 8.9 | |

| Perphenazine enanthate | Trilafon Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 25–200 mg/2 weeks | 2–3 days | ? | 4–7 days | 6.4–7.2 | |

| Pipotiazine palmitate | Piportil Longum | Typical | Viscoleo | 25–400 mg/4 weeks | 9–10 days | ? | 14–21 days | 8.5–11.6 | |

| Pipotiazine undecylenate | Piportil Medium | Typical | Sesame oil | 100–200 mg/2 weeks | ? | ? | ? | 8.4 | |

| Risperidone | Risperdal Consta | Atypical | Microspheres | 12.5–75 mg/2 weeks | 21 days | ? | 3–6 days | – | |

| Zuclopentixol acetate | Clopixol Acuphase | Typical | Viscoleo | 50–200 mg/1–3 days | 1–2 days | 1–2 days | 4.7–4.9 | ||

| Zuclopentixol decanoate | Clopixol Depot | Typical | Viscoleo | 50–800 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–9 days | ? | 11–21 days | 7.5–9.0 | |

| Note: All by intramuscular injection. Footnotes: = Microcrystalline or nanocrystalline aqueous suspension. = Low-viscosity vegetable oil (specifically fractionated coconut oil with medium-chain triglycerides). = Predicted, from PubChem and DrugBank. Sources: Main: See template. | |||||||||

Society and culture

Legal status

Risperidone was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1993 for the treatment of schizophrenia. In 2003, the FDA approved risperidone for the short-term treatment of the mixed and manic states associated with bipolar disorder. In 2006, the FDA approved risperidone for the treatment of irritability in autistic children and adolescents. The FDA's decision was based in part on a study of autistic people with severe and enduring problems of violent meltdowns, aggression, and self-injury; risperidone is not recommended for autistic people with mild aggression and explosive behavior without an enduring pattern. On 22 August 2007, risperidone was approved as the only drug agent available for treatment of schizophrenia in youths, ages 13-17; it was also approved that same day for treatment of bipolar disorder in youths and children, ages 10-17, joining lithium.

On 16 December 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Okedi, intended for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults for whom tolerability and effectiveness has been established with oral risperidone. The applicant for this medicinal product is Laboratorios Farmacéuticos Rovi, S.A. Risperidone was approved for medical use in the European Union in February 2022.

Availability

Janssen's patent on risperidone expired on 29 December 2003, opening the market for cheaper generic versions from other companies, and Janssen's exclusive marketing rights expired on 29 June 2004 (the result of a pediatric extension). It is available under many brand names worldwide.

Risperidone is available as a tablet, an oral solution, and an ampule, which is a depot injection.

Lawsuits

On 11 April 2012, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) and its subsidiary Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. were fined $1.2 billion by Judge Timothy Davis Fox of the Sixth Division of the Sixth Judicial Circuit of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The jury found the companies had downplayed multiple risks associated with risperidone. The verdict was later reversed by the Arkansas State Supreme court.

In August 2012, Johnson & Johnson agreed to pay $181 million to 36 U.S. states in order to settle claims that it had promoted risperidone and paliperidone for off-label uses including for dementia, anger management, and anxiety.

In November 2013, J&J was fined $2.2 billion for illegally marketing risperidone for use in people with dementia.

In 2015, Steven Brill posted a 15-part investigative journalism piece on J&J in The Huffington Post, called "America's most admired lawbreaker", which was focused on J&J's marketing of risperidone.

J&J has faced numerous civil lawsuits on behalf of children who were prescribed risperidone who grew breasts (a condition called gynecomastia); as of July 2016 there were about 1,500 cases in Pennsylvania state court in Philadelphia, and there had been a February 2015 verdict against J&J with $2.5 million awarded to a man from Alabama, a $1.75 million verdict against J&J that November, and in 2016 a $70 million verdict against J&J. In October 2019, a jury awarded a Pennsylvania man $8 billion in a verdict against J&J.

Names

Brand names include Risperdal, Risperdal Consta, Risperdal M-Tab, Risperdal Quicklets, Risperlet, Okedi, and Perseris.

References

- ^ Drugs.com International trade names for risperidone Archived 18 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed 15 March 2016

- ^ "Risperidone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- "Risperdal Consta 25 mg powder and solvent for prolonged-release suspension for injection - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 6 December 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Risperdal- risperidone tablet Risperdal M-Tab- risperidone tablet, orally disintegrating Risperdal- risperidone solution". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Okedi EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 434–435. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ Hasnain M, Vieweg WV, Hollett B (July 2012). "Weight gain and glucose dysregulation with second-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants: a review for primary care physicians". Postgraduate Medicine. 124 (4): 154–67. doi:10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2577. PMID 22913904. S2CID 39697130.

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychopharmacology (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Pub. p. 627. ISBN 9781585623099.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Risperidone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- "Respiridone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- Osser DN, Roudsari MJ, Manschreck T (2013). "The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on schizophrenia". Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 21 (1): 18–40. doi:10.1097/HRP.0b013e31827fd915. PMID 23656760. S2CID 22523977.

- Barry SJ, Gaughan TM, Hunter R (June 2012). "Schizophrenia". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2012. PMC 3385413. PMID 23870705.

- Glick ID, Correll CU, Altamura AC, Marder SR, Csernansky JG, Weiden PJ, et al. (December 2011). "Mid-term and long-term efficacy and effectiveness of antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia: a data-driven, personalized clinical approach". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 72 (12): 1616–27. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06927. PMID 22244023.

- Rattehalli RD, Zhao S, Li BG, Jayaram MB, Xia J, Sampson S (December 2016). "Risperidone versus placebo for schizophrenia" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (12): CD006918. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006918.pub3. PMC 6463908. PMID 27977041. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Schwarz S, Schmid F, Hunger H, Kissling W, Leucht S (January 2011). "Risperidone versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006626. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006626.pub2. PMC 4167865. PMID 21249678.

- Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S (April 2011). "Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia--a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials". Schizophrenia Research. 127 (13): 83–92. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.020. PMID 21257294. S2CID 2386150.

- Lafeuille MH, Dean J, Carter V, Duh MS, Fastenau J, Dirani R, Lefebvre P (August 2014). "Systematic review of long-acting injectables versus oral atypical antipsychotics on hospitalization in schizophrenia". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 30 (8): 1643–55. doi:10.1185/03007995.2014.915211. PMID 24730586. S2CID 24814527.

- Nielsen J, Jensen SO, Friis RB, Valentin JB, Correll CU (May 2015). "Comparative effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injectable vs first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injectables in schizophrenia: results from a nationwide, retrospective inception cohort study". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (3): 627–36. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu128. PMC 4393684. PMID 25180312.

- Muralidharan K, Ali M, Silveira LE, Bond DJ, Fountoulakis KN, Lam RW, Yatham LN (September 2013). "Efficacy of second generation antipsychotics in treating acute mixed episodes in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Affective Disorders. 150 (2): 408–14. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.032. PMID 23735211.

- Nivoli AM, Murru A, Goikolea JM, Crespo JM, Montes JM, González-Pinto A, et al. (October 2012). "New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar mania: a critical review". Journal of Affective Disorders. 140 (2): 125–41. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.015. PMID 22100133.

- Yildiz A, Vieta E, Leucht S, Baldessarini RJ (January 2011). "Efficacy of antimanic treatments: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (2): 375–89. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.192. PMC 3055677. PMID 20980991.

- Peruzzolo TL, Tramontina S, Rohde LA, Zeni CP (2013). "Pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents: an update". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 35 (4): 393–405. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0999. PMID 24402215.

- Gitlin M, Frye MA (May 2012). "Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders". Bipolar Disorders. 14 Suppl 2: 51–65. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00992.x. PMID 22510036. S2CID 21101054.

- Gigante AD, Lafer B, Yatham LN (May 2012). "Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder". CNS Drugs. 26 (5): 403–20. doi:10.2165/11631310-000000000-00000. PMID 22494448. S2CID 2786921.

- Jesner OS, Aref-Adib M, Coren E (January 2007). "Risperidone for autism spectrum disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD005040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005040.pub2. PMC 9022437. PMID 17253538.

- Kirino E (2014). "Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of irritability in autistic children". Clinical Medicine Insights. Pediatrics. 8: 17–30. doi:10.4137/CMPed.S8304. PMC 4051788. PMID 24932108.

- Sharma A, Shaw SR (2012). "Efficacy of risperidone in managing maladaptive behaviors for children with autistic spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 26 (4): 291–9. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.02.008. PMID 22726714.

- McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N, Bruzek JL, Krishnaswami S, Jerome RN, Veenstra-Vanderweele J (May 2011). "A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics. 127 (5): e1312–21. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0427. PMID 21464191. S2CID 2903864.

- Dove D, Warren Z, McPheeters ML, Taylor JL, Sathe NA, Veenstra-VanderWeele J (October 2012). "Medications for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 130 (4): 717–26. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0683. PMC 4074627. PMID 23008452.

- ^ Maher AR, Theodore G (June 2012). "Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 18 (5 Suppl B): S1–20. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.s5-b.1. PMID 22784311.

- "Risperidone: Revised PBS restrictions for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "Antipsychotics and other drug approaches in dementia care | Alzheimer's Society". www.alzheimers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S (April 2013). "Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (3): 557–74. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000740. PMID 22932229.

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press http://www.medicinescomplete.com Archived 10 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N (2014). "Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects". BioMed Research International. 2014: 656370. doi:10.1155/2014/656370. PMC 4065707. PMID 24995318.

- ^ Pillay J, Boylan K, Carrey N, Newton A, Vandermeer B, Nuspl M, MacGregor T, Jafri SH, Featherstone R, Hartling L (March 2017). "First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Children and Young Adults: Systematic Review Update". Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (184): ES–24. PMID 28749632. Report 17-EHC001-EF. Bookshelf ID: NBK442352.

Compared with FGAs, SGAs may decrease the risk for experiencing any extrapyramidal symptom (EPS). FGAs probably cause lower gains in weight and BMI.

- Pillinger, Toby; McCutcheon, Robert A; Vano, Luke; Mizuno, Yuya; Arumuham, Atheeshaan; Hindley, Guy; Beck, Katherine; Natesan, Sridhar; Efthimiou, Orestis; Cipriani, Andrea; Howes, Oliver D (2020-01). "Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (1): 64–77. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30416-X. PMC 7029416. PMID 31860457.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - Wang, J. S.; Ruan, Y.; Taylor, R. M.; Donovan, J. L.; Markowitz, J. S.; Devane, C. L. (2004). "The Brain Entry of Risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone Is Greatly Limited by P-glycoprotein". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (4): 415–9. doi:10.1017/S1461145704004390. PMID 15683552.

- Gurley BJ, Swain A, Williams DK, Barone G, Battu SK (July 2008). "Gauging the clinical significance of P-glycoprotein-mediated herb-drug interactions: comparative effects of St. John's wort, Echinacea, clarithromycin, and rifampin on digoxin pharmacokinetics". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 52 (7): 772–9. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700081. PMC 2562898. PMID 18214850.

- BMJ Group, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISSN 0260-535X.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- Chouinard G, Jones BD (January 1980). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis: clinical and pharmacologic characteristics". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.1.16. PMID 6101522.

- Miller R, Chouinard G (November 1993). "Loss of striatal cholinergic neurons as a basis for tardive and L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis and refractory schizophrenia". Biological Psychiatry. 34 (10): 713–38. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(93)90044-E. PMID 7904833. S2CID 2405709.

- Chouinard G, Jones BD, Annable L (November 1978). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 135 (11): 1409–10. doi:10.1176/ajp.135.11.1409. PMID 30291.

- Seeman P, Weinshenker D, Quirion R, Srivastava LK, Bhardwaj SK, Grandy DK, et al. (March 2005). "Dopamine supersensitivity correlates with D2High states, implying many paths to psychosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (9): 3513–8. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.3513S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409766102. PMC 548961. PMID 15716360.

- Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655. S2CID 6267180.

- National Institute of Mental Health. PDSD Ki Database (Internet) . ChapelHill (NC): University of North Carolina. 1998-2013. Available from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Smith C, Rahman T, Toohey N, Mazurkiewicz J, Herrick-Davis K, Teitler M (October 2006). "Risperidone irreversibly binds to and inactivates the h5-HT7 serotonin receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 70 (4): 1264–70. doi:10.1124/mol.106.024612. PMID 16870886. S2CID 1678887.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

- Abou El-Magd RM, Park HK, Kawazoe T, Iwana S, Ono K, Chung SP, et al. (July 2010). "The effect of risperidone on D-amino acid oxidase activity as a hypothesis for a novel mechanism of action in the treatment of schizophrenia". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 1055–67. doi:10.1177/0269881109102644. PMID 19329549. S2CID 39050369.

- "Psychopharmacology Institute". Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Hecht EM, Landy DC (February 2012). "Alpha-2 receptor antagonist add-on therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia; a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 134 (2–3): 202–6. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.030. PMID 22169246. S2CID 36119981.

- Brauner, Jan M.; Hessler, Sabine; Groemer, Teja W.; Alzheimer, Christian; Huth, Tobias (2014). "Risperidone inhibits voltage-gated sodium channels". European Journal of Pharmacology. 728: 100–106. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.062. PMID 24508524.

- "The DrugBank database". Archived from the original on 17 November 2011.

- Parent M, Toussaint C, Gilson H (1983). "Long-term treatment of chronic psychotics with bromperidol decanoate: clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation". Current Therapeutic Research. 34 (1): 1–6.

- ^ Jørgensen A, Overø KF (1980). "Clopenthixol and flupenthixol depot preparations in outpatient schizophrenics. III. Serum levels". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 279: 41–54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb07082.x. PMID 6931472.

- ^ Reynolds JE (1993). "Anxiolytic sedatives, hypnotics and neuroleptics.". Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 364–623.

- Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Davis CM, Richards A, Seidel DR (May 1984). "Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (5 Pt 2): 50–9. PMID 6143748.

- ^ Curry SH, Whelpton R, de Schepper PJ, Vranckx S, Schiff AA (April 1979). "Kinetics of fluphenazine after fluphenazine dihydrochloride, enanthate and decanoate administration to man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 7 (4): 325–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00941.x. PMC 1429660. PMID 444352.

- Young D, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Garcia N (1984). Explaining the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine through computer simulations. (Abstract.). 19th Annual Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Dallas, Texas.

- Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, Schellekens KH, Lenaerts FM, Verbruggen FJ, van Nueten JM, Marsboom RH, Hérin VV, Schaper WK (November 1970). "The pharmacology of fluspirilene (R 6218), a potent, long-acting and injectable neuroleptic drug". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 20 (11): 1689–98. PMID 4992598.

- Beresford R, Ward A (January 1987). "Haloperidol decanoate. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in psychosis". Drugs. 33 (1): 31–49. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733010-00002. PMID 3545764.

- Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, Gelders YG, Aerts TJ (1982). "Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 (4): 238–46. doi:10.1159/000468580. PMID 7185768.

- Larsson M, Axelsson R, Forsman A (1984). "On the pharmacokinetics of perphenazine: a clinical study of perphenazine enanthate and decanoate". Current Therapeutic Research. 36 (6): 1071–88.

- "Electronic Orange Book". Food and Drug Administration. April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- "FDA approves the first drug to treat irritability associated with autism, Risperdal" (Press release). FDA. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- Scahill L (July 2008). "How do I decide whether or not to use medication for my child with autism? Should I try behavior therapy first?". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 38 (6): 1197–8. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0573-7. PMID 18463973. S2CID 20767044.

- ^ "Okedi: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- "Companies belittled risks of Risperdal, slapped with huge fine" Archived 12 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, 11 April 2012.

- Thomas K (20 March 2014). "Arkansas Court Reverses $1.2 Billion Judgment Against Johnson & Johnson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015.

- "NY AG: Janssen pays $181M over drug marketing". The Seattle Times. 30 August 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016.

- "Johnson & Johnson to Pay More Than $2.2 Billion to Resolve Criminal and Civil Investigations". Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Ashbrook T (22 September 2015). "Johnson & Johnson And The Big Lies Of Big Pharma". On Point. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016.

- Brill S (September 2015). "America's Most Admired Lawbreaker". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- Feeley J (1 July 2016). "J&J Hit With $70 Million Risperdal Verdict Over Male Breasts". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017.

- "Jury says J&J must pay $8 billion in case over male breast growth linked to Risperdal". Reuters. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "Risperidone: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

Further reading

- Dean L (2017). "Risperidone Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520384. Bookshelf ID: NBK425795.

External links

- "Risperidone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

| Galactagogues | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolactin receptor agonists | |||||

| Prolactin releasers |

| ||||

| Others |

| ||||

- Alpha-1 blockers

- Alpha-2 blockers

- Atypical antipsychotics

- Treatment of autism

- Schering-Plough brands

- Belgian inventions

- Benzisoxazoles

- Fluoroarenes

- Galactagogues

- H1 receptor antagonists

- Johnson & Johnson brands

- Janssen Pharmaceutica

- Lactams

- Mood stabilizers

- Piperidines

- Prolactin releasers

- Pyrimidones

- Serotonin receptor antagonists

- World Health Organization essential medicines