| Revision as of 22:40, 9 November 2023 editBillinghurst (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Administrators46,695 edits not official website← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:52, 29 December 2023 edit undoFineCreatures (talk | contribs)98 edits →Architecture and decoration: added content from new sourceTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

| == Architecture and decoration == | == Architecture and decoration == | ||

| The Comnenian building was a church with a main aisle and two ''deambulatoria'',<ref>A ''deambulatorium'' is an aisle which encircles the central part of a church</ref> three ]s, and a ] to the west. The ] was typical of the Comnenian period, and used the ''recessed brick'' technique. In this technique, alternate courses of brick are mounted behind the line of the wall, and are plunged in a mortar's bed, which can still be seen in the ] underneath and in the church.<ref name=ma346/> | The Comnenian building was a church with a main aisle and two ''deambulatoria'',<ref>A ''deambulatorium'' is an aisle which encircles the central part of a church</ref> three ]s, and a ] to the west. The ] was typical of the Comnenian period, and used the ''recessed brick'' technique. In this technique, alternate courses of brick are mounted behind the line of the wall, and are plunged in a mortar's bed, which can still be seen in the ] underneath and in the church.<ref name=ma346/> Its unusual plan in which the central space in enwrapped by the ] stretching down both sides as well as the usual main exit/entrance west end, has been speculated by architectural historians such as Ousterhout to maximize the amount of burial space near the central space, the naos.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ousterhout |first=Robert |url=https://pressbooks.pub/smarthistoryguidetobyzantineart/chapter/middle-byzantine-church-architecture/ |title=A Smarthistory Guide to Byzantine Art |date=2021 |publisher=Smarthistory |editor-last=Freeman |editor-first=Evan |chapter=Middle Byzantine Church Architecture}}</ref> | ||

| The transformation of the church into a mosque greatly changed the original building. The arcades connecting the main ] with the deambulatoria were removed and replaced with broad arches to open up the nave. The three apses were removed too. In their place towards the east a great domed room was built at an oblique angle to the orientation of the building. | The transformation of the church into a mosque greatly changed the original building. The arcades connecting the main ] with the deambulatoria were removed and replaced with broad arches to open up the nave. The three apses were removed too. In their place towards the east a great domed room was built at an oblique angle to the orientation of the building. | ||

| On the other side, the parekklesion represents the most beautiful building of the late Byzantine period in ]. It has the typical ] plan with five domes, but the proportion between vertical and horizontal dimensions is much |

On the other side, the parekklesion represents what is sometimes considered the most beautiful building of the late Byzantine period in ]. It has the typical ] plan with five domes, but the proportion between vertical and horizontal dimensions is much more attenuated than usual (although not so big as in the contemporary Byzantine churches built in the Balkans). | ||

| Although the inner colored marble revetment largely disappeared, the shrine still contains the restored remains of a number of ] panels, which, while not as varied and well-preserved as those of the Chora Church, serve as another resource for understanding late Byzantine art. | Although the inner colored marble revetment largely disappeared, the shrine still contains the restored remains of a number of ] panels, which, while not as varied and well-preserved as those of the Chora Church, serve as another resource for understanding late Byzantine art. | ||

Revision as of 22:52, 29 December 2023

Greek Orthodox Byzantine church in Istanbul, Turkey "Fethiye Mosque" redirects here. For other uses, see Fethiye Mosque (disambiguation).| Pammakaristos Church | |

|---|---|

| Μονή Παμμακάριστου Fethiye Camii | |

Pammakaristos Church Pammakaristos Church | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam (currently) Greek Orthodox Church (previously) |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°01′45″N 28°56′47″E / 41.02917°N 28.94639°E / 41.02917; 28.94639 |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Byzantine architecture, Greek architecture, Islamic |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

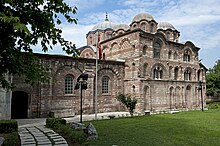

The Pammakaristos Church, also known as the Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos (Template:Lang-el, "All-Blessed Mother of God"), is one of the most famous Byzantine churches in Istanbul, Turkey, and was the last pre-Ottoman building to house the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Converted in 1591 into the Fethiye Mosque (Template:Lang-tr, "mosque of the conquest"), it is today partly a museum housed in a side chapel or parekklesion. One of the most important examples of Constantinople's Palaiologan architecture, the church contains the largest quantity of Byzantine mosaics in Istanbul after the Hagia Sophia and Chora Church.

The church-mosque is in the Çarşamba neighbourhood of the Fatih district inside the walled city of Istanbul.

History

Most scholars believe that the church was built between the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Many historians and archaeologists attribute the original structure to Michael VII Ducas (1071–1078); others put its foundation in the Comnenian period. Alternatively, the Swiss scholar and Byzantinist Ernest Mamboury suggested that the original building belonged to the 8th century.

The parekklesion (side chapel) was added to the south side of the church in the early Palaiologan period, and dedicated to Christos ho Logos (Template:Lang-el). Shortly after 1310, Martha Glabas erected a small shrine in memory of her late husband, the protostrator Michael Doukas Glabas Tarchaneiote, a general of Andronikos II Palaiologos. An elegant dedicatory inscription to Christ, written by the poet Manuel Philes, runs along the inside and outside of the parekklesion.

The main church was also renovated at the same time, as the study of the Templon has shown.

Following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate was first moved from Hagia Sophia to the Church of the Holy Apostles. Then in 1456 it was moved to the Theotokos Pammakaristos Church, where it remained until 1587.

Five years later, the Ottoman Sultan Murad III converted the church into a mosque and renamed it in honor of his conquest (fetih) of Georgia and Azerbaijan, hence the name Fethiye Camii. To accommodate the requirements of prayer, most of the interior walls were removed to create a larger inner space.

After years of neglect, the complex was restored in 1949 by the Byzantine Institute of America and Dumbarton Oaks. While the main building remains a mosque, the parekklesion has been a museum since then.

In 2021 restoration work on the building began again. It was due to be completed by the end of 2022.

Architecture and decoration

The Comnenian building was a church with a main aisle and two deambulatoria, three apses, and a narthex to the west. The masonry was typical of the Comnenian period, and used the recessed brick technique. In this technique, alternate courses of brick are mounted behind the line of the wall, and are plunged in a mortar's bed, which can still be seen in the cistern underneath and in the church. Its unusual plan in which the central space in enwrapped by the ambulatory stretching down both sides as well as the usual main exit/entrance west end, has been speculated by architectural historians such as Ousterhout to maximize the amount of burial space near the central space, the naos.

The transformation of the church into a mosque greatly changed the original building. The arcades connecting the main aisle with the deambulatoria were removed and replaced with broad arches to open up the nave. The three apses were removed too. In their place towards the east a great domed room was built at an oblique angle to the orientation of the building.

On the other side, the parekklesion represents what is sometimes considered the most beautiful building of the late Byzantine period in Constantinople. It has the typical cross-in-square plan with five domes, but the proportion between vertical and horizontal dimensions is much more attenuated than usual (although not so big as in the contemporary Byzantine churches built in the Balkans).

Although the inner colored marble revetment largely disappeared, the shrine still contains the restored remains of a number of mosaic panels, which, while not as varied and well-preserved as those of the Chora Church, serve as another resource for understanding late Byzantine art.

A representation of the Pantocrator, surrounded by the prophets of the Old Testament (Moses, Jeremiah, Zephaniah, Micah, Joel, Zechariah, Obadiah, Habakkuk, Jonah, Malachi, Ezekiel, and Isaiah) fills the main dome. In the apse, Christ Hyperagathos is shown with the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist. A Baptism of Christ survives intact to the right side of the dome.

-

Fethiye Museum exterior

Fethiye Museum exterior

-

Fethiye Museum exterior

Fethiye Museum exterior

-

Fethiye Museum Exterior

Fethiye Museum Exterior

-

Fethiye Museum domes

Fethiye Museum domes

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic in a dome

Fethiye Museum mosaic in a dome

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic with Saint Antony, the desert Father

Fethiye Museum mosaic with Saint Antony, the desert Father

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic of Saint Antony, the desert Father

Fethiye Museum mosaic of Saint Antony, the desert Father

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic Christ

Fethiye Museum mosaic Christ

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic Saint Gregory of Great Armenia

Fethiye Museum mosaic Saint Gregory of Great Armenia

-

Fethiye Museum mosaic

Fethiye Museum mosaic

-

Fethiye Museum capital

Fethiye Museum capital

In the building with the Fethiye Museum (with an entrance in the street passing the garden where the entrance to the museum is) a part is still a mosque. Here are some pictures of its interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

-

Fethiye Mosque interior

Fethiye Mosque interior

See also

Notes

- ^ Mathews (1976), p. 346

- Mamboury, (1933)

- Mathews (1976), p. 347. Logos in the Eastern Orthodox Theology is the denomination of the second Person of the Trinity

- ^ Mathews (1976), p. 347.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 133.

- Entrance tickets, which up to some months ago had to be bought at Haghia Sophia, are now for sale at the parekklesion.

- A deambulatorium is an aisle which encircles the central part of a church

- Ousterhout, Robert (2021). "Middle Byzantine Church Architecture". In Freeman, Evan (ed.). A Smarthistory Guide to Byzantine Art. Smarthistory.

References

- Mamboury, Ernest (1933). Byzance - Constantinople - Istanbul (in French) (3 ed.). Istanbul: Milli Neşriyat Yurdu.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (1976). The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01210-2.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Belting, Hans; Mouriki, Doula; Mango, Cyril (1978). Mosaics and Frescoes of St Mary Pammakaristos (Fethiye Cami Istanbul). Dumbarton Oaks Pub Service. ISBN 0-88402-075-4.

- Harris, Jonathan (2007). Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. Hambledon/Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-179-4.

External links

- Byzantium 1200 | Pammakaristos Monastery

- 130 pictures of the church

- Some more pictures of the mosque

- History and Mosaics of the Pammakaristos

| Byzantine Empire topics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||