| Revision as of 22:26, 30 March 2024 edit2002:8919:eec9:0:4067:169f:5580:a136 (talk) Added discovery of outbursts in 1217 and 1787.Tags: Reverted Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:51, 30 March 2024 edit undoSomethingintheshadows (talk | contribs)16 edits Overly close paraphrase and this is already included and cited in the intro. Could probably be wrapped into first description paragraphTag: UndoNext edit → | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

| ] of T Coronae Borealis during the time surrounding its 1946 eruption, plotted from ] data]] | ] of T Coronae Borealis during the time surrounding its 1946 eruption, plotted from ] data]] | ||

| T CrB normally has a ] of about 10, which is near the limit of typical binoculars. Outbursts have been seen twice, reaching magnitude 2.0 on May 12, 1866 and magnitude 3.0 on February 9, 1946,<ref name=Sanford1949/> although a more recent paper shows the 1866 outburst with a possible peak range of magnitude 2.5 ± 0.5.<ref name=Schaefer2009/> Even when at peak magnitude of 2.5, this ] is dimmer than about 120 stars in the night sky.<ref name="SIMBAD-mag2.5">{{cite web |title=Vmag<2.5 |publisher=SIMBAD Astronomical Database |url=http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-sam?Criteria=Vmag%3C2.5 |accessdate=2010-06-25}}</ref> It is sometimes nicknamed the ''Blaze Star''.<ref>, 34. Unusual Stellar Spectra III: two emission-line stars</ref> | T CrB normally has a ] of about 10, which is near the limit of typical binoculars. Outbursts have been seen twice, reaching magnitude 2.0 on May 12, 1866 and magnitude 3.0 on February 9, 1946,<ref name=Sanford1949/> although a more recent paper shows the 1866 outburst with a possible peak range of magnitude 2.5 ± 0.5.<ref name=Schaefer2009/> Even when at peak magnitude of 2.5, this ] is dimmer than about 120 stars in the night sky.<ref name="SIMBAD-mag2.5">{{cite web |title=Vmag<2.5 |publisher=SIMBAD Astronomical Database |url=http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-sam?Criteria=Vmag%3C2.5 |accessdate=2010-06-25}}</ref> It is sometimes nicknamed the ''Blaze Star''.<ref>, 34. Unusual Stellar Spectra III: two emission-line stars</ref> | ||

| In March 2024, B. E. Schaefer of Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, reported the discovery of an apparent long-lost nova eruption of T CrB at visual magnitude somewhat brighter than +2, based on the eyewitness report of Burchard, Abbot of the Ursberg Abbey (near Augsberg, Germany), in the autumn of the year 1217. This record appears in Latin in the Ursperger Chronicle, a medieval monastic annal written in the year 1225, and the nova was one of the two most important events of the year. | |||

| Schaefer further reported his discovery of an eruption at visual magnitude somewhat brighter than 7.8, based on unpublished letters and catalogs of the English astronomer Rev. Francis Wollaston (F.R.S., Chislehurst, England). Wollaston first mentioned the star in a letter to Sir William Herschel, dated 1787 Dec. 28. | |||

| T CrB is a ] containing a large cool component and a smaller hot component. The cool component is a ] which is transferring material to the hot component. The hot component is a ] surrounded by an ], all hidden inside a dense cloud of material from the red giant. When the system is quiescent, the red giant dominates the visible light output and the system appears as an ] giant. The hot component contributes some emission and dominates the ] output. During outbursts, the transfer of material to the hot component increases greatly, the hot component expands, and the luminosity of the system increases.<ref name=linford/><ref name=stanishev/><ref name=ilkiewicz/><ref name=luna/> | T CrB is a ] containing a large cool component and a smaller hot component. The cool component is a ] which is transferring material to the hot component. The hot component is a ] surrounded by an ], all hidden inside a dense cloud of material from the red giant. When the system is quiescent, the red giant dominates the visible light output and the system appears as an ] giant. The hot component contributes some emission and dominates the ] output. During outbursts, the transfer of material to the hot component increases greatly, the hot component expands, and the luminosity of the system increases.<ref name=linford/><ref name=stanishev/><ref name=ilkiewicz/><ref name=luna/> | ||

Revision as of 23:51, 30 March 2024

Recurrent nova in the constellation Corona BorealisNot to be confused with Tau Coronae Borealis.

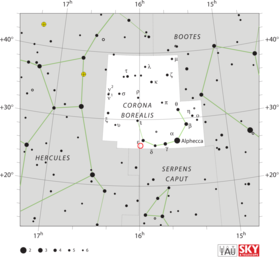

Location of T Coronae Borealis (circled in red)

Location of T Coronae Borealis (circled in red) | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Corona Borealis |

| Right ascension | 15 59 30.1622 |

| Declination | 25° 55′ 12.613″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 2.0–10.8 |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Red giant + white dwarf |

| Spectral type | M3III+p |

| Variable type | recurrent nova |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −27.79 km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −4.220 mas/yr Dec.: 12.364 mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 1.2127 ± 0.0488 mas |

| Distance | 806+34 −30 pc |

| Orbit | |

| Period (P) | 227.8 d |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.54 AU |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.0 |

| Inclination (i) | 67° |

| Details | |

| Red giant | |

| Mass | 1.12 M☉ |

| Radius | 75 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 655 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.0 cgs |

| Temperature | 3,600 K |

| White dwarf | |

| Mass | 1.37 M☉ |

| Luminosity | ~100 L☉ |

| Other designations | |

| BD+26° 2765, HD 143454, HIP 78322, SAO 84129, 2MASS J15593015+2555126 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

T Coronae Borealis (T CrB), is a recurrent nova in the constellation Corona Borealis. It was first discovered in outburst in 1866 by John Birmingham, although it had been observed earlier as a 10th magnitude star. It may have been observed in 1217 and in 1787 as well.

Description

T CrB normally has a magnitude of about 10, which is near the limit of typical binoculars. Outbursts have been seen twice, reaching magnitude 2.0 on May 12, 1866 and magnitude 3.0 on February 9, 1946, although a more recent paper shows the 1866 outburst with a possible peak range of magnitude 2.5 ± 0.5. Even when at peak magnitude of 2.5, this recurrent nova is dimmer than about 120 stars in the night sky. It is sometimes nicknamed the Blaze Star.

T CrB is a binary system containing a large cool component and a smaller hot component. The cool component is a red giant which is transferring material to the hot component. The hot component is a white dwarf surrounded by an accretion disc, all hidden inside a dense cloud of material from the red giant. When the system is quiescent, the red giant dominates the visible light output and the system appears as an M3 giant. The hot component contributes some emission and dominates the ultraviolet output. During outbursts, the transfer of material to the hot component increases greatly, the hot component expands, and the luminosity of the system increases.

The two components of the system orbit each other every 228 days. The orbit is almost circular and is inclined at an angle of 67°. The stars are separated by 0.54 AU.

2016–present activity

On 20 April 2016, the Sky & Telescope website reported a sustained brightening since February 2015 from magnitude 10.5 to about 9.2. A similar event was reported in 1938, followed by another outburst in 1946. By June 2018, the star had dimmed slightly but still remained at an unusually high level of activity. In March or April 2023, it dimmed to magnitude 12.3. A similar dimming occurred in the year before the 1946 outburst, indicating that it will likely erupt between March and September 2024.

References

- ^ Gaia Collaboration; et al. (November 2016). "Gaia Data Release 1. Summary of the astrometric, photometric, and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 595: 23. arXiv:1609.04172. Bibcode:2016A&A...595A...2G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629512. S2CID 1828208. A2.

- ^ Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- Shenavrin, V. I.; Taranova, O. G.; Nadzhip, A. E. (2011). "Search for and study of hot circumstellar dust envelopes". Astronomy Reports. 55 (1): 31–81. Bibcode:2011ARep...55...31S. doi:10.1134/S1063772911010070. S2CID 122700080.

- Pourbaix, D.; Tokovinin, A. A.; Batten, A. H.; Fekel, F. C.; Hartkopf, W. I.; Levato, H.; Morrell, N. I.; Torres, G.; Udry, S. (2004). "SB9: The ninth catalogue of spectroscopic binary orbits". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 424 (2): 727–732. arXiv:astro-ph/0406573. Bibcode:2004A&A...424..727P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041213. S2CID 119387088.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Linford, Justin D.; Chomiuk, Laura; Sokoloski, Jennifer L.; Weston, Jennifer H. S.; Van Der Horst, Alexander J.; Mukai, Koji; Barrett, Paul; Mioduszewski, Amy J.; Rupen, Michael (2019). "T CRB: Radio Observations during the 2016-2017 "Super-active" State". The Astrophysical Journal. 884 (1): 8. arXiv:1909.13858. Bibcode:2019ApJ...884....8L. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab3c62. S2CID 203593955.

- ^ Fekel, Francis C.; Joyce, Richard R.; Hinkle, Kenneth H.; Skrutskie, Michael F. (2000). "Infrared Spectroscopy of Symbiotic Stars. I. Orbits for Well-Known S-Type Systems". The Astronomical Journal. 119 (3): 1375. Bibcode:2000AJ....119.1375F. doi:10.1086/301260.

- ^ Stanishev, V.; Zamanov, R.; Tomov, N.; Marziani, P. (2004). "Hα variability of the recurrent nova T Coronae Borealis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 415 (2): 609–616. arXiv:astro-ph/0311309. Bibcode:2004A&A...415..609S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034623. S2CID 3000175.

- Schaefer, Bradley E. (2009). "Orbital Periods for Three Recurrent Novae". The Astrophysical Journal. 697 (1): 721–729. arXiv:0903.1349. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697..721S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/721. S2CID 16087253.

- ^ Wallerstein, George; Harrison, Tanya; Munari, Ulisse; Vanture, Andrew (2008). "The Metallicity and Lithium Abundances of the Recurring Novae T CrB and RS Oph". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 120 (867): 492. Bibcode:2008PASP..120..492W. doi:10.1086/587965. S2CID 106406607.

- Andrews, Robin George (8 March 2024). "The Night Sky Will Soon Get 'a New Star.' Here's How to See It. - A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago, and astronomers say it's expected to put on another show in the coming months". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Pettit, Edison (1946). "The Light-Curves of T Coronae Borealis". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 58 (341): 153. Bibcode:1946PASP...58..153P. doi:10.1086/125797.

- Barnard, E. E. (1907). "Nova T Coronae of 1866". Astrophysical Journal. 25: 279. Bibcode:1907ApJ....25..279B. doi:10.1086/141446.

- "The recurrent nova T CrB had prior eruptions observed near December 1787 and October 1217 AD". Journal for the History of Astronomy. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- "Evidence of mysterious 'recurring nova' that could reappear in 2024 found in medieval manuscript from 1217". Live Science. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- Sanford, Roscoe F. (1949). "High-Dispersion Spectrograms of T Coronae Borealis". Astrophysical Journal. 109: 81. Bibcode:1949ApJ...109...81S. doi:10.1086/145106.

- Schaefer, Bradley E. (2010). "Comprehensive Photometric Histories of All Known Galactic Recurrent Novae". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 187 (2): 275–373. arXiv:0912.4426. Bibcode:2010ApJS..187..275S. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/187/2/275. S2CID 119294221.

- "Vmag<2.5". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- A Digital Spectral Classification Atlas, R. O. Gray, 34. Unusual Stellar Spectra III: two emission-line stars

- Iłkiewicz, Krystian; Mikołajewska, Joanna; Stoyanov, Kiril; Manousakis, Antonios; Miszalski, Brent (2016). "Active phases and flickering of a symbiotic recurrent nova T CrB". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (3): 2695. arXiv:1607.06804. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462.2695I. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1837. S2CID 119104759.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Luna, GJM; Mukai, K.; Sokoloski, J. L.; Nelson, T.; Kuin, P.; Segreto, A.; Cusumano, G.; Jaque Arancibia, M.; Nuñez, N. E. (2018). "Dramatic change in the boundary layer in the symbiotic recurrent nova T Coronae Borealis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 619 (1): 61. arXiv:1807.01304. Bibcode:2018A&A...619A..61L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833747. S2CID 119078482.

- "Is T CrB About to Blow its Top?". Sky & Telescope website. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- Schaefer, B.E.; Kloppenborg, B.; Waagen, E.O. "Announcing T CrB pre-eruption dip". AAVSO. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- Todd, Ian. "T Coronae Borealis nova event guide and how to prepare". Sky at Night Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

Further reading

- Wallerstein, George; Tanya Harrison; Ulisse Munari; Andrew Vanture (11 May 2008). "The Metallicity and Lithium Abundances of the Recurring Novae T CrB and RS Oph". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 120 (867): 492–497. Bibcode:2008PASP..120..492W. doi:10.1086/587965. S2CID 106406607.

- R and T Coronae Borealis: Two Stellar Opposites Archived 2012-04-06 at the Wayback Machine at Sky & Telescope

External links

- http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/B/Blaze_Star.html

- AAVSO: Quick Look View of AAVSO Observations (get recent magnitude estimates for T CrB)

| Constellation of Corona Borealis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stars |

| ||||||||||

| Exoplanets |

| ||||||||||

| Galaxies |

| ||||||||||

| Galaxy clusters |

| ||||||||||