| Revision as of 01:01, 29 September 2024 editGuy Harris (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users76,652 edits Use citation templates.← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:15, 29 September 2024 edit undoGuy Harris (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users76,652 edits Use a citation template.Next edit → | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

| === Threaded SMS === | === Threaded SMS === | ||

| Threaded SMS is a visual styling orientation of SMS message history that arranges messages to and from a contact in chronological order on a single screen. It was first invented by a developer working to implement the SMS client for the BlackBerry, who was looking to make use of the blank screen left below the message on a device with a larger screen capable of displaying far more than the usual 160 characters, and was inspired by threaded Reply conversations in email.<ref> |

Threaded SMS is a visual styling orientation of SMS message history that arranges messages to and from a contact in chronological order on a single screen. It was first invented by a developer working to implement the SMS client for the BlackBerry, who was looking to make use of the blank screen left below the message on a device with a larger screen capable of displaying far more than the usual 160 characters, and was inspired by threaded Reply conversations in email.<ref>{{US patent|7028263}}</ref> | ||

| Visually, this style of representation provides a back-and-forth chat-like history for each individual contact.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.phonescoop.com/glossary/term.php?gid=455 |title=Threaded Messaging |website=Phone Scoop |access-date=29 September 2024}}</ref> Hierarchical-threading at the ] (as typical in blogs and online messaging boards) is not widely supported by SMS messaging clients. This limitation is due to the fact that there is no ] or subject-line passed back and forth between sent and received messages in the ] data (as specified by SMS protocol) from which the client device can properly thread an incoming message to a specific dialogue, or even to a specific message within a dialogue. | Visually, this style of representation provides a back-and-forth chat-like history for each individual contact.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.phonescoop.com/glossary/term.php?gid=455 |title=Threaded Messaging |website=Phone Scoop |access-date=29 September 2024}}</ref> Hierarchical-threading at the ] (as typical in blogs and online messaging boards) is not widely supported by SMS messaging clients. This limitation is due to the fact that there is no ] or subject-line passed back and forth between sent and received messages in the ] data (as specified by SMS protocol) from which the client device can properly thread an incoming message to a specific dialogue, or even to a specific message within a dialogue. | ||

Revision as of 06:15, 29 September 2024

Text messaging service component For other uses, see SMS (disambiguation). For text messaging in general, see Text messaging.

Short Message Service, commonly abbreviated as SMS, is a text messaging service component of most telephone, Internet and mobile device systems. It uses standardized communication protocols that let mobile phones exchange short text messages, typically transmitted over cellular networks.

Developed as part of the GSM standards, and based on the SS7 signalling protocol, SMS rolled out on digital cellular networks starting in 1993 and was originally intended for customers to receive alerts from their carrier/operator. The service allows users to send and receive text messages of up to 160 characters, originally to and from GSM phones and later also CDMA and Digital AMPS; it has since been defined and supported on newer networks, including present-day 5G ones. Using SMS gateways, messages can be transmitted over the Internet through an SMSC, allowing communication to computers, fixed landlines, and satellite. MMS was later introduced as an upgrade to SMS with "picture messaging" capabilities.

In addition to recreational texting between people, SMS is also used for mobile marketing (a type of direct marketing), two-factor authentication logging-in, televoting, mobile banking (see SMS banking), and for other commercial content. The SMS standard has been hugely popular worldwide as a method of text communication: by the end of 2010, it was the most widely used data application with an estimated 3.5 billion active users, or about 80% of all mobile phone subscribers. More recently, SMS has become increasingly challenged by newer proprietary instant messaging services; RCS has been designated as the potential open standard successor to SMS.

Developmental history

SMS technology originated from radio telegraphy in radio memo pagers that used standardized phone protocols. These were defined in 1986 as part of the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) series of standards. The first SMS message was sent on 3 December 1992, when Neil Papworth, a test engineer for Sema Group, sent "Merry Christmas" to the Orbitel 901 phone of colleague Richard Jarvis.

Initial concept

Adding text messaging functionality to mobile devices began in the early 1980s. The first action plan of the CEPT Group GSM was approved in December 1982, requesting that "The services and facilities offered in the public switched telephone networks and public data networks ... should be available in the mobile system." This plan included the exchange of text messages either directly between mobile stations, or transmitted via message handling systems in use at that time.

The SMS concept was developed in the Franco-German GSM cooperation in 1984 by Friedhelm Hillebrand and Bernard Ghillebaert. The GSM is optimized for telephony, since this was identified as its main application. The key idea for SMS was to use this telephone-optimized system, and to transport messages on the signalling paths needed to control the telephone traffic during periods when no signalling traffic existed. In this way, unused resources in the system could be used to transport messages at minimal cost. However, it was necessary to limit the length of the messages to 128 bytes (later improved to 160 seven-bit characters) so that the messages could fit into the existing signalling formats. Based on his personal observations and on analysis of the typical lengths of postcard and Telex messages, Hillebrand argued that 160 characters was sufficient for most brief communications.

SMS could be implemented in every mobile station by updating its software. Hence, a large base of SMS-capable terminals and networks existed when people began to use SMS. A new network element required was a specialized short message service centre, and enhancements were required to the radio capacity and network transport infrastructure to accommodate growing SMS traffic.

Early development

The technical development of SMS was a multinational collaboration supporting the framework of standards bodies. Through these organizations the technology was made freely available to the whole world.

The first proposal which initiated the development of SMS was made by a contribution of Germany and France in the GSM group meeting in February 1985 in Oslo. This proposal was further elaborated in GSM subgroup WP1 Services (Chairman Martine Alvernhe, France Telecom) based on a contribution from Germany. There were also initial discussions in the subgroup WP3 network aspects chaired by Jan Audestad (Telenor). The result was approved by the main GSM group in a June 1985 document which was distributed to industry. The input documents on SMS had been prepared by Friedhelm Hillebrand of Deutsche Telekom, with contributions from Bernard Ghillebaert of France Télécom. The definition that Friedhelm Hillebrand and Bernard Ghillebaert brought into GSM called for the provision of a message transmission service of alphanumeric messages to mobile users "with acknowledgement capabilities". The last three words transformed SMS into something much more useful than the electronic paging services used at the time that some in GSM might have had in mind.

SMS was considered in the main GSM group as a possible service for the new digital cellular system. In GSM document "Services and Facilities to be provided in the GSM System," both mobile-originated and mobile-terminated short messages appear on the table of GSM teleservices.

The discussions on the GSM services were concluded in the recommendation GSM 02.03 "TeleServices supported by a GSM PLMN." Here a rudimentary description of the three services was given:

- Short message mobile-terminated (SMS-MT)/ Point-to-Point: the ability of a network to transmit a Short Message to a mobile phone. The message can be sent by phone or by a software application.

- Short message mobile-originated (SMS-MO)/ Point-to-Point: the ability of a network to transmit a Short Message sent by a mobile phone. The message can be sent to a phone or to a software application.

- Short message cell broadcast.

The material elaborated in GSM and its WP1 subgroup was handed over in Spring 1987 to a new GSM body called IDEG (the Implementation of Data and Telematic Services Experts Group), which had its kickoff in May 1987 under the chairmanship of Friedhelm Hillebrand (German Telecom). The technical standard known today was largely created by IDEG (later WP4) as the two recommendations GSM 03.40 (the two point-to-point services merged) and GSM 03.41 (cell broadcast).

WP4 created a Drafting Group Message Handling (DGMH), which was responsible for the specification of SMS. Finn Trosby of Telenor chaired the draft group through its first three years, in which the design of SMS was established. DGMH had five to eight participants, and Finn Trosby mentions as major contributors Kevin Holley, Eija Altonen, Didier Luizard and Alan Cox. The first action plan mentions for the first time the Technical Specification 03.40 "Technical Realisation of the Short Message Service". Responsible editor was Finn Trosby. The first and very rudimentary draft of the technical specification was completed in November 1987. However, drafts useful for the manufacturers followed at a later stage in the period. A comprehensive description of the work in this period is given in.

The work on the draft specification continued in the following few years, where Kevin Holley of Cellnet (now Telefónica O2 UK) played a leading role. Besides the completion of the main specification GSM 03.40, the detailed protocol specifications on the system interfaces also needed to be completed.

Early implementations

The first SMS message was sent over the Vodafone GSM network in the United Kingdom on 3 December 1992, from Neil Papworth of Sema Group (now Mavenir Systems) using a personal computer to Richard Jarvis of Vodafone using an Orbitel 901 handset. The text of the message was "Merry Christmas."

The first commercial deployment of a short message service center (SMSC) was by Aldiscon part of Logica (now part of CGI) with Telia (now TeliaSonera) in Sweden in 1993, followed by Fleet Call (now Nextel) in the US, Telenor in Norway and BT Cellnet (now O2 UK) later in 1993. All first installations of SMS gateways were for network notifications sent to mobile phones, usually to inform of voice mail messages.

The first commercially sold SMS service was offered to consumers, as a person-to-person text messaging service by Radiolinja (now part of Elisa) in Finland in 1993. Most early GSM mobile phone handsets did not support the ability to send SMS text messages, and Nokia was the only handset manufacturer whose total GSM phone line in 1993 supported user-sending of SMS text messages. According to Matti Makkonen, an engineer at Nokia at the time, the Nokia 2010, which was released in January 1994, was the first mobile phone to support composing SMSes easily.

Growth and adoption

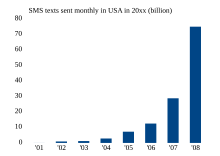

Initial growth was slow, with customers in 1995 sending on average only 0.4 messages per GSM customer per month. Initially, networks in the UK only allowed customers to send messages to other users on the same network, limiting the usefulness of the service. This restriction was lifted in 1999. Over time, this issue was eliminated by switch billing instead of billing at the SMSC and by new features within SMSCs to allow blocking of foreign mobile users sending messages through it. By the end of 2000, the average number of messages reached 35 per user per month, and on Christmas Day 2006, over 205 million messages were sent in the UK alone. SMS had become a social phenomenon in Finland among teens and youngsters by 1999. SMS traffic across Europe reached 4 billion messages as of January 2000.

It had become extremely popular in the Philippines by 2001 and the country was dubbed the "texting capital of the world", partly helped by large numbers of free text messages offered by the mobile operators in monthly subscriptions. SMS adoption was limited to parts of Europe and Asia during these earlier years, with U.S. adoption being low partly due to incompatible networks and cheap voice calls relative to other countries. The Economist wrote in 2003, as noted by an analyst:

The short answer is that, in America, talk is cheap. Because local calls on land lines are usually free, wireless operators have to offer big “bundles” of minutes—up to 5,000 minutes per month—as part of their monthly pricing plans to persuade subscribers to use mobile phones instead. Texting first took off in other parts of the world among cost-conscious teenagers who found that it was cheaper to text than to call Free local calls also make logging on to the internet, for hours at a time, and using PC-to-PC “instant messaging” (IM) the preferred mode of electronic chat among American teenagers.

This is also backed by the fact that as of 2003, American internet users were spending on average five times more time online than Europeans, and many poorer countries in Europe and other regions around the world had significantly lower rates of internet access compared to the United States at the time (see digital divide), hence making SMS more accessible.

Contemporary usage

| Country | Monthly messages sent per mobile subscriber (2003) |

|---|---|

| Philippines | 195 |

| South Korea | 120 |

| Ireland | 79 |

| Croatia | 72 |

| Indonesia | 68 |

| France | 19 |

| United States | 13 |

SMS has become a large commercial industry, earning $114.6 billion globally in 2010. In the year 2002, 366 billion SMS text messages were sent globally, a number that rose to 6.1 trillion (6.1 × 10) in 2010, which is an average of 193,000 messages per second. The global average price for an SMS message is US$0.11, while mobile networks charge each other interconnect fees of at least US$0.04 when connecting between different phone networks. In 2015, the actual cost of sending an SMS in Australia was found to be $0.00016 per SMS. The global SMS messaging business was estimated to be worth over US$240 billion in 2013, accounting for almost half of all revenue generated by mobile messaging.

The popularity of SMS also led to the spontaneous creation of the so-called 'SMS language' phenomenon, where words are shortened in order to deal with the 160 character limit of SMS messages. Usage of SMS for mobile data services became increasingly prominent in the early 2000s due to its ubiquity, reliability, and cold reception of the newer WAP standard. (see Premium-rated services below). In the early and mid 2000s, Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) was developed as an improved version of SMS that supports sending of pictures and video.

SMS has been increasingly challenged by Internet Protocol-based messaging services with additional features for modern mobile devices, such as Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Telegram, or WeChat. These services run independently from mobile network operators and typically don't provide cross-platform messaging capabilities like SMS or email does. For example, between 2010 and 2022, SMS telecom revenue in India dropped 94 percent, while "revenue share per user from data usage...grew over 10 times.", although in some regions such as North America SMS continues to be used by over 80 percent of the population as of 2023. In order to create a modern successor to SMS that isn't run by a single company and is fully interoperable between devices, industry figures have created the RCS 'Universal Profile' initiative. It was supported by Apple when iOS 18 came out in 2024, which will mean that virtually all new mobile phones (iOS and Android platforms) will have RCS texting capabilities, though this may also depend on if the network operator supports it.

Premium-rated services

See also: Reverse SMS billing and Short codeSMS may be used to provide premium rate services to subscribers of a network. Mobile-terminated short messages can be used to deliver digital content such as news alerts, financial information, logos, and ringtones. The first premium-rate media content delivered via the SMS system was the world's first paid downloadable ringing tones, as commercially launched by Saunalahti (later Jippii Group, now part of Elisa Group), in 1998. Initially, only Nokia branded phones could handle them. By 2002 the ringtone business globally had exceeded $1 billion of service revenues, and nearly US$5 billion by 2008. Today, they are also used to pay smaller payments online—for example, for file-sharing services, in mobile application stores, or VIP section entrance. Outside the online world, one can buy a bus ticket or beverages from ATM, pay a parking ticket, order a store catalog or some goods (e.g., discount movie DVDs), make a donation to charity, and much more.

Other uses

Additionally, an intermediary service can facilitate a text-to-voice conversion to be sent to landlines.

In 2014, Caktus Group developed the world's first SMS-based voter registration system in Libya. As of February 2015 more than 1.5 million people have registered using that system, providing Libyan voters with unprecedented access to the democratic process.

SMS enablement allows individuals to send an SMS message to a business phone number (traditional landline) and receive a SMS in return. Providing customers with the ability to text to a phone number allows organizations to offer new services that deliver value. Examples include chat bots, and text enabled customer service and call centers.

Flash SMS

A Flash SMS is a type of SMS that appears directly on the main screen without user interaction and is not automatically stored in the inbox. It can be useful in emergencies, such as a fire alarm or cases of confidentiality, as in delivering one-time passwords.

Silent SMS

In 2010, almost half a million silent SMS messages were sent by the German federal police, customs and the federal domestic intelligence service Verfassungsschutz. These silent messages, also known as silent TMS, stealth SMS, stealth ping or Short Message Type 0, are used to locate a person and thus to create a complete movement profile. They do not show up on a display, nor trigger any acoustical signal when received. Their primary purpose was to deliver special services of the network operator to any cell phone.

SMS bombs

In March 2001, Dutch police in Amsterdam attempted to fight increasing cell phone theft by sending an SMS every three minutes to a phone that has been reported stolen, with the message "This handset was nicked, buying or selling is a crime. The police."

Text messaging outside GSM

SMS was originally designed as part of GSM, but is now available on a wide range of networks globally, including 3G, 4G and 5G networks. However, not all text messaging systems use SMS, and some notable alternative implementations of the concept include J-Phone's SkyMail and NTT Docomo's Short Mail, both in Japan. Email messaging from phones, as popularized by NTT Docomo's i-mode and the RIM BlackBerry, also typically uses standard mail protocols such as SMTP over TCP/IP.

Technical details

GSM

Main article: Short message service technical realisation (GSM)The Short Message Service—Point to Point (SMS-PP)—was originally defined in GSM recommendation 03.40, which is now maintained in 3GPP as TS 23.040. GSM 03.41 (now 3GPP TS 23.041) defines the Short Message Service—Cell Broadcast (SMS-CB), which allows messages (advertising, public information, etc.) to be broadcast to all mobile users in a specified geographical area.

Messages are sent to a short message service center (SMSC), which provides a "store and forward" mechanism. It attempts to send messages to the SMSC's recipients. If a recipient is not reachable, the SMSC queues the message for later retry. Some SMSCs also provide a "forward and forget" option where transmission is tried only once. Both mobile terminated (MT, for messages sent to a mobile handset) and mobile originating (MO, for those sent from the mobile handset) operations are supported. Message delivery is "best effort", so there are no guarantees that a message will actually be delivered to its recipient, but delay or complete loss of a message is uncommon, typically affecting less than 5 percent of messages. Some providers allow users to request delivery reports, either via the SMS settings of most modern phones, or by prefixing each message with *0# or *N#. However, the exact meaning of confirmations varies from reaching the network, to being queued for sending, to being sent, to receiving a confirmation of receipt from the target device, and users are often not informed of the specific type of success being reported.

SMS is a stateless communication protocol in which every SMS message is considered entirely independent of other messages. Enterprise applications using SMS as a communication channel for stateful dialogue (where an MO reply message is paired to a specific MT message) requires that session management be maintained external to the protocol.

Message size

Transmission of short messages between the SMSC and the handset is done whenever using the Mobile Application Part (MAP) of the SS7 protocol. Messages are sent with the MAP MO- and MT-ForwardSM operations, whose payload length is limited by the constraints of the signaling protocol to precisely 140 bytes (140 bytes × 8 bits / byte = 1120 bits).

Short messages can be encoded using a variety of alphabets: the default GSM 7-bit alphabet, the 8-bit data alphabet, and the 16-bit UCS-2 or UTF-16 alphabets. Depending on which alphabet the subscriber has configured in the handset, this leads to the maximum individual short message sizes of 160 7-bit characters, 140 8-bit characters, or 70 16-bit characters. GSM 7-bit alphabet support is mandatory for GSM handsets and network elements, but characters in languages such as Hindi, Arabic, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, or Cyrillic alphabet languages (e.g., Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Bulgarian, etc.) must be encoded using the 16-bit UCS-2 character encoding (see Unicode). Routing data and other metadata is additional to the payload size.

Larger content (concatenated SMS, multipart or segmented SMS, or "long SMS") can be sent using multiple messages, in which case each message will start with a User Data Header (UDH) containing segmentation information. Since UDH is part of the payload, the number of available characters per segment is lower: 153 for 7-bit encoding, 134 for 8-bit encoding and 67 for 16-bit encoding. The receiving handset is then responsible for reassembling the message and presenting it to the user as one long message. While the standard theoretically permits up to 255 segments, 10 segments is the practical maximum with some carriers, and long messages are often billed as equivalent to multiple SMS messages. In some cases 127 segments are supported, but software limitations in some SMS applications do not permit this. Some providers have offered length-oriented pricing schemes for messages, although that type of pricing structure is rapidly disappearing.

Gateway providers

SMS gateway providers facilitate SMS traffic between businesses and mobile subscribers, including SMS for enterprises, content delivery, and entertainment services involving SMS, e.g. TV voting. Considering SMS messaging performance and cost, as well as the level of messaging services, SMS gateway providers can be classified as aggregators or SS7 providers.

The aggregator model is based on multiple agreements with mobile carriers to exchange two-way SMS traffic into and out of the operator's SMSC, also known as "local termination model". Aggregators lack direct access into the SS7 protocol, which is the protocol where the SMS messages are exchanged. SMS messages are delivered to the operator's SMSC, but not the subscriber's handset; the SMSC takes care of further handling of the message through the SS7 network.

Another type of SMS gateway provider is based on SS7 connectivity to route SMS messages, also known as "international termination model". The advantage of this model is the ability to route data directly through SS7, which gives the provider total control and visibility of the complete path during SMS routing. This means SMS messages can be sent directly to and from recipients without having to go through the SMSCs of other mobile operators. Therefore, it is possible to avoid delays and message losses, offering full delivery guarantees of messages and optimized routing. This model is particularly efficient when used in mission-critical messaging and SMS used in corporate communications. Moreover, these SMS gateway providers are providing branded SMS services with masking but after misuse of these gateways most countries' governments have taken serious steps to block these gateways.

Interconnectivity with other networks

Message Service Centers communicate with the Public Land Mobile Network (PLMN) or PSTN via Interworking and Gateway MSCs.

Subscriber-originated messages are transported from a handset to a service center, and may be destined for mobile users, subscribers on a fixed network, or Value-Added Service Providers (VASPs), also known as application-terminated. Subscriber-terminated messages are transported from the service center to the destination handset, and may originate from mobile users, from fixed network subscribers, or from other sources such as VASPs.

On some carriers nonsubscribers can send messages to a subscriber's phone using an Email-to-SMS gateway. Additionally, many carriers, including AT&T Mobility, T-Mobile USA, Sprint, and Verizon Wireless, offer the ability to do this through their respective websites.

For example, an AT&T subscriber whose phone number was 555-555-5555 would receive emails addressed to 5555555555@txt.att.net as text messages. Subscribers can easily reply to these SMS messages, and the SMS reply is sent back to the original email address. Sending email to SMS is free for the sender, but the recipient is subject to the standard delivery charges. Only the first 160 characters of an email message can be delivered to a phone, and only 160 characters can be sent from a phone. However, longer messages may be broken up into multiple texts, depending upon the telephone service provider.

Text-enabled fixed-line handsets are required to receive messages in text format. However, messages can be delivered to non enabled phones using text-to-speech conversion.

Short messages can send binary content such as ringtones or logos, as well as Over-the-air programming (OTA) or configuration data. Such uses are a vendor-specific extension of the GSM specification and there are multiple competing standards, although Nokia's Smart Messaging is common.

SMS is used for M2M (Machine to Machine) communication. For instance, there is an LED display machine controlled by SMS, and some vehicle tracking companies use SMS for their data transport or telemetry needs. SMS usage for these purposes is slowly being superseded by GPRS services owing to their lower overall cost. GPRS is offered by smaller telco players as a route of sending SMS text to reduce the cost of SMS texting internationally.

Support in other architectures

The Mobile Application Part (MAP) of the SS7 protocol included support for the transport of Short Messages through the Core Network from its inception. MAP Phase 2 expanded support for SMS by introducing a separate operation code for Mobile Terminated Short Message transport. Since Phase 2, there have been no changes to the Short Message operation packages in MAP, although other operation packages have been enhanced to support CAMEL SMS control.

From 3GPP Releases 99 and 4 onwards, CAMEL Phase 3 introduced the ability for the Intelligent Network (IN) to control aspects of the Mobile Originated Short Message Service, while CAMEL Phase 4, as part of 3GPP Release 5 and onwards, provides the IN with the ability to control the Mobile Terminated service. CAMEL allows the gsmSCP to block the submission (MO) or delivery (MT) of Short Messages, route messages to destinations other than that specified by the user, and perform real-time billing for the use of the service. Prior to standardized CAMEL control of the Short Message Service, IN control relied on switch vendor specific extensions to the Intelligent Network Application Part (INAP) of SS7.

AT commands

Many mobile and satellite transceiver units support the sending and receiving of SMS using an extended version of the Hayes command set. The extensions were standardised as part of the GSM Standards and extended as part of the 3GPP standards process.

The connection between the terminal equipment and the transceiver can be realized with a serial cable (e.g., USB), a Bluetooth link, an infrared link, etc. Common AT commands include AT+CMGS (send message), AT+CMSS (send message from storage), AT+CMGL (list messages) and AT+CMGR (read message).

However, not all modern devices support receiving of messages if the message storage (for instance the device's internal memory) is not accessible using AT commands.

Premium-rated short messages

The Value-added service provider (VASP) providing premium-rate content submits the message to the mobile operator's SMSC(s) using a TCP/IP protocol such as the short message peer-to-peer protocol (SMPP) or the External Machine Interface (EMI). The SMSC delivers the text using the normal Mobile Terminated delivery procedure. The subscribers are charged extra for receiving this premium content; the revenue is typically divided between the mobile network operator and the VASP either through revenue share or a fixed transport fee. Submission to the SMSC is usually handled by a third party.

Mobile-originated short messages may also be used in a premium-rated manner for services such as televoting. In this case, the VASP providing the service obtains a short code from the telephone network operator, and subscribers send texts to that number. The payouts to the carriers vary by carrier; percentages paid are greatest on the lowest-priced premium SMS services. Most information providers should expect to pay about 45 percent of the cost of the premium SMS up front to the carrier. The submission of the text to the SMSC is identical to a standard MO Short Message submission, but once the text is at the SMSC, the Service Center (SC) identifies the Short Code as a premium service. The SC will then direct the content of the text message to the VASP, typically using an IP protocol such as SMPP or EMI. Subscribers are charged a premium for the sending of such messages, with the revenue typically shared between the network operator and the VASP. Short codes only work within one country, they are not international.

An alternative to inbound SMS is based on long numbers (international number format, such as "+44 762 480 5000"), which can be used in place of short codes for SMS reception in several applications, such as TV voting, product promotions and campaigns. Long numbers work internationally, allow businesses to use their own numbers, rather than short codes, which are usually shared across many brands. Additionally, long numbers are nonpremium inbound numbers.

Threaded SMS

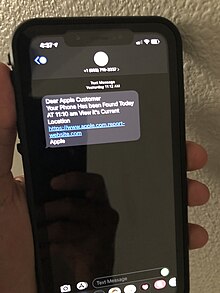

Threaded SMS is a visual styling orientation of SMS message history that arranges messages to and from a contact in chronological order on a single screen. It was first invented by a developer working to implement the SMS client for the BlackBerry, who was looking to make use of the blank screen left below the message on a device with a larger screen capable of displaying far more than the usual 160 characters, and was inspired by threaded Reply conversations in email.

Visually, this style of representation provides a back-and-forth chat-like history for each individual contact. Hierarchical-threading at the conversation-level (as typical in blogs and online messaging boards) is not widely supported by SMS messaging clients. This limitation is due to the fact that there is no session identifier or subject-line passed back and forth between sent and received messages in the header data (as specified by SMS protocol) from which the client device can properly thread an incoming message to a specific dialogue, or even to a specific message within a dialogue.

Most smart phone text-messaging-clients are able to create some contextual threading of "group messages" which narrows the context of the thread around the common interests shared by group members. On the other hand, advanced enterprise messaging applications which push messages from a remote server often display a dynamically changing reply number (multiple numbers used by the same sender), which is used along with the sender's phone number to create session-tracking capabilities analogous to the functionality that cookies provide for web-browsing. As one pervasive example, this technique is used to extend the functionality of many Instant Messenger (IM) applications such that they are able to communicate over two-way dialogues with the much larger SMS user-base. In cases where multiple reply numbers are used by the enterprise server to maintain the dialogue, the visual conversation threading on the client may be separated into multiple threads.

Application-to-person (A2P) SMS

While SMS reached its popularity as a person-to-person messaging, another type of SMS is growing fast: application-to-person (A2P) messaging. A2P is a type of SMS sent from a subscriber to an application or sent from an application to a subscriber. It is commonly used by businesses, such as banks, e-gaming, logistic companies, e-commerce, to send SMS messages from their systems to their customers.

In the US, carriers have traditionally preferred that A2P messages must be sent using a short code rather than a standard long code. However, recently multiple US carriers, including Verizon have announced plans to officially support A2P messages over long codes. In the United Kingdom A2P messages can be sent with a dynamic 11 character sender ID; however, short codes are used for OPTOUT commands.

Satellite phone networks

All commercial satellite phone networks except ACeS and OptusSat support SMS. While early Iridium handsets only support incoming SMS, later models can also send messages. The price per message varies for different networks. Unlike some mobile phone networks, there is no extra charge for sending international SMS or to send one to a different satellite phone network. SMS can sometimes be sent from areas where the signal is too poor to make a voice call.

Satellite phone networks usually have web-based or email-based SMS portals where one can send free SMS to phones on that particular network.

Unreliability

Unlike dedicated texting systems like the Simple Network Paging Protocol and Motorola's ReFLEX protocol, SMS message delivery is not guaranteed, and many implementations provide no mechanism through which a sender can determine whether an SMS message has been delivered in a timely manner. SMS messages are generally treated as lower-priority traffic than voice, and various studies have shown that around 1% to 5% of messages are lost entirely, even during normal operation conditions, and others may not be delivered until long after their relevance has passed. The use of SMS as an emergency notification service in particular has been questioned.

Vulnerabilities

The Global Service for Mobile communications (GSM), with the greatest worldwide number of users, succumbs to several security vulnerabilities. In the GSM, only the airway traffic between the Mobile Station (MS) and the Base Transceiver Station (BTS) is optionally encrypted with a weak and broken stream cipher (A5/1 or A5/2). The authentication is unilateral and also vulnerable. There are also many other security vulnerabilities and shortcomings. Such vulnerabilities are inherent to SMS as one of the superior and well-tried services with a global availability in the GSM networks. SMS messaging has some extra security vulnerabilities due to its store-and-forward feature, and the problem of fake SMS that can be conducted via the Internet. When a user is roaming, SMS content passes through different networks, perhaps including the Internet, and is exposed to various vulnerabilities and attacks. Another concern arises when an adversary gets access to a phone and reads the previous unprotected messages.

In October 2005, researchers from Pennsylvania State University published an analysis of vulnerabilities in SMS-capable cellular networks. The researchers speculated that attackers might exploit the open functionality of these networks to disrupt them or cause them to fail, possibly on a nationwide scale.

SMS spoofing

Main article: SMS spoofingThe GSM industry has identified a number of potential fraud attacks on mobile operators that can be delivered via abuse of SMS messaging services. The most serious threat is SMS Spoofing, which occurs when a fraudster manipulates address information in order to impersonate a user that has roamed onto a foreign network and is submitting messages to the home network. Frequently, these messages are addressed to destinations outside the home network—with the home SMSC essentially being "hijacked" to send messages into other networks.

The only sure way of detecting and blocking spoofed messages is to screen incoming mobile-originated messages to verify that the sender is a valid subscriber and that the message is coming from a valid and correct location. This can be implemented by adding an intelligent routing function to the network that can query originating subscriber details from the home location register (HLR) before the message is submitted for delivery. This kind of intelligent routing function is beyond the capabilities of legacy messaging infrastructure.

Limitation

In an effort to limit telemarketers who had taken to bombarding users with hordes of unsolicited messages, India introduced new regulations in September 2011, including a cap of 3,000 SMS messages per subscriber per month, or an average of 100 per subscriber per day. Due to representations received from some of the service providers and consumers, TRAI (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India) has raised this limit to 200 SMS messages per SIM per day in case of prepaid services, and up to 6,000 SMS messages per SIM per month in case of postpaid services with effect from November 1, 2011. However, it was ruled unconstitutional by the Delhi high court, but there are some limitations.

See also

- Process driven messaging service

- Comparison of mobile phone standards

- Instant messaging

- Thumbing

- Data Coding Scheme

- Enhanced Messaging Service (EMS)

- Short message service technical realisation (GSM)

- SMS hubbing

- SMS home routing

- SMS language

- BCODE

Notes

- Specifically 140 bytes, allowing 160 7-bit (i.e. entirely alpha-numeric) characters, 140 8-bit characters, or 70 2-byte characters in languages such as Chinese when encoded using UTF-16 character encoding.

References

- O'Mahony, Jennifer (3 December 2012). "How SMS Changed the World". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "A short history of SMS for anyone working in Telecommunications". www.dynamicmobilebilling.com. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- "When First SMS Was Sent". Play GK Quiz. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- Ghribi, Brahim; Logrippo, Luigi (November 2000). "Understanding GPRS: The GSM Packet Radio Service" (PDF). Computer Networks (journal). 34 (5): 763–779 – via University of Ottawa.

- "How SMS gateway works". Ozeki SMS Gateway. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- Black, Ken (September 13, 2016). "What is SMS Marketing?". wiseGEEK. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- "What is SMS 2FA? | Security Encyclopedia". www.hypr.com. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- "Eurovision facts and figures". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- "Short Message Service (SMS) in Fixed and Mobile Networks". European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations. July 2004.

- ^ "The World Today – The rise of 3G" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Features, Chris Gayomali last updated in (2012-12-03). "The text message turns 20: A brief history of SMS". theweek. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ Junge, Jack (2017-02-27). "RCS: Next Generation SMS". GatewayAPI. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ GSM Doc 28/85 "Services and Facilities to be provided in the GSM System" rev2, June 1985

- ^ "Hppy bthdy txt!". BBC News. 3 December 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-01-20.

- Kleinman, Zoe. "'Merry Christmas': 30 years of the text message". Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- "Vintage Mobiles". History of GSM. Orbitel 901 – the first GSM mobile and the first to receive a commercial SMS text message (1992). Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- see GSM document 02/82, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- These Message Handling Systems had been standardized in the ITU, see specifications X.400 series

- See the book Hillebrand, Trosby, Holley, Harris: SMS the creation of Personal Global Text Messaging, Wiley 2010

- "Technology". May 3, 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- See GSM document 28/85rev.June 2, 85 and GSM WP1 document 66/86, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- ETSI, TC-SMG. "Digital cellular telecommunications system (Phase 2+); Technical realization of the Short Message Service (SMS)" (PDF). etsi.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-12-12. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- See also Friedhelm Hillebrand "GSM and UMTS, the creation of Global Mobile Communication", Wiley 2002, chapters 10 and 16, ISBN 0-470-84322-5

- GSM document 19/85, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- GSM document 28/85r2, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- "So who really did create SMS?". Stephen Temple. February 24, 2013. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "Teleservices Supported by a GSM Public Land Mobile Network (PLMN)". GSM TS 02.03.

- Document GSM IDEG 79/87r3, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- GSM 03.40, WP4 document 152/87, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- Finn Trosby (2004). "SMS the strange duckling of GSM" (PDF). Telektronikk. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007.

- "UK hails 10th birthday of SMS". The Times of India. 4 December 2002.

- "First commercial deployment of Text Messaging (SMS)". Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- US Department of Homeland Security. "Cellular Technologies" (PDF). Electronic Frontier Foundation). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2012.

- "Our history in Norway". Telenor Group. 1993. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

Telenor leads in establishing GSM (2G) – the SMS service was a part of this platform

- "BT unveils new mobile brand". BBC News Online. September 3, 2001. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Nael, Merili (June 30, 2015). "Suri tekstisõnumite looja Matti Makkonen" [Creator of text messages Matti Makkonen died]. Err.ee (in Estonian). Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ "More Than 200 Billion GSM Text Messages Forecast for Full Year 2001" (Press release). GSM Association. 12 February 2001. Archived from the original on February 15, 2002.

- Crystal, David (July 5, 2008). "2b or not 2b?". Guardian Unlimited. London, UK. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- Silberman, Steve. "Just Say Nokia". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- "Towards the Full Roll-Out of Third Generation Mobile Communications". European Union Law. 11 June 2002.

- "The Philippine text messaging phenomenon | Philstar.com". www.philstar.com. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- Celdran, David (January 2002). "The Philippines: SMS and Citizenship". Development Dialogue. 1 (1): 91–103.

- ^ "Je ne texte rien". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- "Europe, Asia embrace GR8 way to stay in touch". NBC News. 2004-04-23. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- "No text please, we're American". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- "Will instant messaging be the new texting?". 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- Kapitsa, L. (12 December 2007). "Member-countries of the UNECE region are among the forerunners and today's leaders in the level of Internet development..." United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

DOC file download

- "The Rise of Text Messaging [INFOGRAPHIC]". Mashable. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-08-18.

- Matthews, Charles H.; Brueggemann, Ralph (2015). Innovation and Entrepreneurship: A Competency Framework (First ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-74252-8. OCLC 893453493.

- "Etisalat launches MMS service". Khaleej Times. 2003-07-16. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- Han, Esther (May 6, 2015). "Cheaper mobile calls and text as ACCC moves to slash wholesale fees". Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015 – via The Age.

- Portio Research. "Mobile Messaging Futures 2014-20148". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- "BBC News | E-CYCLOPEDIA | Txt msging: Th shp of thngs 2 cm?". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- "SMS: Mobile data's dark horse hits its stride". 2001-04-13. Archived from the original on 2001-04-13. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- "It's a hamster on your mobile. Or possibly Kylie". 2002-05-13. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- "The death of SMS is exaggerated". 13 June 2011. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Online apps slash telecoms revenue: 80% decline in voice calls, 94% drop in SMS in 10 years". Hindustan Times. 2023-07-09. Archived from the original on 2023-11-11. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- Brouwers, Christel. "SMS: Popularity, Statistics, and Use Cases". CM.com. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- "RCS Messaging Finally Lands on Your iPhone With the iOS 18 Public Betas". CNET. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ Rossignuolo, Vincenza (2021). "SMS codes [Explained]". SMSglobal.

- "BBC News | UK | Text messaging grows up". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- Kelly, Heather (December 3, 2012). "OMG, The Text Message Turns 20. But has SMS peaked?". CNN. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "Caktus Group". Archived from the original on 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- "Libya's Election Ushers in New Voter Tech". World Policy Institute. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "SMS types on routomessaging.com". Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- "Flash SMS". Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- Reitman, Rainey (10 January 2012). "Privacy Roundup: Mandatory Data Retention, Smart Meter Hacks, and Law Enforcement Usage of Silent SMS". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Zoll, BKA und Verfassungsschutz verschickten 2010 über 440.000 "stille SMS" | heise online". Heise.de. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- "3GPP TS 51.010-1 version 12.5.0 Release 12" (PDF). ETSI. September 2015. pp. 3418–3423. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- "CNN.com - SMS bombs nominated for crime-fighting prize - August 30, 2001". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- "Dutch police fight cell phone theft with SMS bombs". 2001-04-13. Archived from the original on 2001-04-13. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- "Specification # 03.40". Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Specification # 23.040". Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Specification # 03.41". Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Specification # 23.041". Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- Gil Held: "Data over Wireless Networks." pages 105–11, 137–38. Wiley, 2001.

- Oliver, Earl, Design and Implementation of a Short Message Service Data Channel for Mobile Systems (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2022, retrieved March 14, 2022

- "Text Message Tips (not sent or received)". community.o2.co.uk. December 9, 2018. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- Amri, Kuross. "Communication Networks". Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Chad Selph (2012-11-08). "Adventures in Unicode SMS". Twilio. Archived from the original on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ^ "Alphabets and language-specific information". 3GPP TS 23.038.

- Groves, Ian (1998). Mobile systems (1st ed.). London: Springer. pp. 70, 79, 163–66. ISBN 978-1-4615-6377-8. OCLC 847640648. Archived from the original on 2024-01-11. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- "Does Twilio support concatenated SMS messages or messages over 160 characters?". Twilio Support. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

when sending very long SMS messages (longer than 10 segments with Unicode characters) some mobile carriers may have trouble handling these messages.

- "Simplifying Unicode punctuation for SMS". ssb22.user.srcf.net. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- "t-zones text messaging: send and receive messages with mobile text messaging". T-mobile.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- "Support – How do I compose and send a text message to a Sprint or Nextel customer from email?". Support.sprintpcs.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- "Answers to FAQs – Verizon Wireless Support". Support.vzw.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- "Is there a maximum SMS message length?". TextAnywhere. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- Hill, Simon; Revilla, Andre (28 April 2022). "How to send a text message from your email account". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

Keep in mind that if you're trying to send a message that's more than 160 characters long, it will often be sent through the Multimedia Message Service (MMS).

- Leyden, John (January 2004). "BT trials mobile SMS to voice landline". The Register. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- Ewan (September 1, 2006). "10pText.co.uk help you text internationally for 10p/text". SMStextnews. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ "Mobile Application Part (MAP) Specification".

- ^ "Customised Applications for Mobile network Enhanced Logic (CAMEL)". 3GPP TS 23.078.

- "Use of Data Terminal Equipment – Data Circuit terminating Equipment (DTE – DCE) interface for Short Message Service (SMS) and Cell Broadcast Service (CBS)". Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "SMS Tutorial: Introduction to AT Commands, Basic Commands and Extended Commands". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- Agarwal, Tarun (2019-09-18). "What are AT Commands : Different Types, and Their List". ElProCus – Electronic Projects for Engineering Students. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

- U.S. patent 7,028,263

- "Threaded Messaging". Phone Scoop. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- "Whitepaper: Market Opportunities for Text and MMS Messaging" ABI Research, 2011

- "What is A2P (Application-to-person) SMS Messaging? | Glossary". www.infobip.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Long Code Vs Short Code – What's The Difference?". Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Commercial Long Code SMS Product and Fee Structure Changes on Verizon". Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- "Motorola's ReFLEX Protocol Delivers Wireless Data With Unparelleled Nationwide Network Coverage". July 17, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Report Says That SMS is Not Ideal for Emergency Communications". cellular-news. Archived from the original on January 25, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "SMS Testing: Text Message Delivery Time and Reliability in Tanzania". 31 August 2011.

- "Solutions to the GSM Security Weaknesses". Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Applications, Services, and Technologies (NGMAST2008). Cardiff, UK. September 2008. pp. 576–581. arXiv:1002.3175. doi:10.1109/NGMAST.2008.88.

- "SSMS – A Secure SMS Messaging Protocol for the M-Payment Systems". Proceedings of the 13th IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC'08). July 2008. pp. 700–705. arXiv:1002.3171. doi:10.1109/ISCC.2008.4625610.

- "Exploiting Open Functionality in SMS-Capable Cellular Networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the 12th ACM conference on Computer and communications security. Alexandria, Virginia, USA. 7–11 November 2005. pp. 393–404. doi:10.1145/1102120.1102171. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-30.

- "An overview on how to stop SMS Spoofing in mobile operator networks (September 9, 2008)". Archived from the original on September 26, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Nirmala Ganapathy (September 27, 2011). "3,000 SMS a Month Limit in India From Today". Straits Times Indonesia. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- "TRAI extends the 100 SMS per day per SIM limit to 200 SMS per day per SIM" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- "TRAI cap on SMS goes". The Hindu. January 26, 2012. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

External links

- 3GPP – the organization that maintains the SMS specification

- ISO Standards (In Zip file format)

- GSM 03.38 to Unicode – how the GSM 7-bit default alphabet characters map into Unicode

| Mobile phones | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile networks, protocols |

| ||||||

| General operation | |||||||

| Mobile devices |

| ||||||

| Mobile specific software |

| ||||||

| Culture | |||||||

| Environment and health | |||||||

| Law | |||||||