| Revision as of 21:25, 13 December 2024 edit2600:6c50:7200:1d71:79af:1bbe:895e:4083 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:00, 16 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,406,598 edits Altered url. URLs might have been anonymized. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Dominic3203 | Linked from User:Qwfp/bkm | #UCB_webform_linked 3/5Next edit → | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

| ====Static semantics==== | ====Static semantics==== | ||

| Static semantics defines restrictions on the structure of valid texts that are hard or impossible to express in standard syntactic formalisms.<ref name="Aaby 2004"/>{{Failed verification|date=January 2023|reason=This site says nothing about "static semantics" or any connection between semantics and "structure" or "restrictions".}} For compiled languages, static semantics essentially include those semantic rules that can be checked at compile time. Examples include checking that every ] is declared before it is used (in languages that require such declarations) or that the labels on the arms of a ] are distinct.<ref>Michael Lee Scott, ''Programming language pragmatics'', Edition 2, Morgan Kaufmann, 2006, {{ISBN|0-12-633951-1}}, p. 18–19</ref> Many important restrictions of this type, like checking that identifiers are used in the appropriate context (e.g. not adding an integer to a function name), or that ] calls have the appropriate number and type of arguments, can be enforced by defining them as rules in a ] called a ]. Other forms of ] like ] may also be part of static semantics. Programming languages such as ] and ] have ], a form of data flow analysis, as part of their respective static semantics.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Winskel |first=Glynn |url=https://books.google. |

Static semantics defines restrictions on the structure of valid texts that are hard or impossible to express in standard syntactic formalisms.<ref name="Aaby 2004"/>{{Failed verification|date=January 2023|reason=This site says nothing about "static semantics" or any connection between semantics and "structure" or "restrictions".}} For compiled languages, static semantics essentially include those semantic rules that can be checked at compile time. Examples include checking that every ] is declared before it is used (in languages that require such declarations) or that the labels on the arms of a ] are distinct.<ref>Michael Lee Scott, ''Programming language pragmatics'', Edition 2, Morgan Kaufmann, 2006, {{ISBN|0-12-633951-1}}, p. 18–19</ref> Many important restrictions of this type, like checking that identifiers are used in the appropriate context (e.g. not adding an integer to a function name), or that ] calls have the appropriate number and type of arguments, can be enforced by defining them as rules in a ] called a ]. Other forms of ] like ] may also be part of static semantics. Programming languages such as ] and ] have ], a form of data flow analysis, as part of their respective static semantics.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Winskel |first=Glynn |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JzUNn6uUxm0C |title=The Formal Semantics of Programming Languages: An Introduction |date=5 February 1993 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-0-262-73103-4 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| ====Dynamic semantics==== | ====Dynamic semantics==== | ||

Revision as of 14:00, 16 December 2024

Language for communicating instructions to a machine

A programming language is a system of notation for writing computer programs. Programming languages are described in terms of their syntax (form) and semantics (meaning), usually defined by a formal language. Languages usually provide features such as a type system, variables, and mechanisms for error handling. An implementation of a programming language is required in order to execute programs, namely an interpreter or a compiler. An interpreter directly executes the source code, while a compiler produces an executable program.

Computer architecture has strongly influenced the design of programming languages, with the most common type (imperative languages—which implement operations in a specified order) developed to perform well on the popular von Neumann architecture. While early programming languages were closely tied to the hardware, over time they have developed more abstraction to hide implementation details for greater simplicity.

Thousands of programming languages—often classified as imperative, functional, logic, or object-oriented—have been developed for a wide variety of uses. Many aspects of programming language design involve tradeoffs—for example, exception handling simplifies error handling, but at a performance cost. Programming language theory is the subfield of computer science that studies the design, implementation, analysis, characterization, and classification of programming languages.

Definitions

Programming languages differ from natural languages in that natural languages are used for interaction between people, while programming languages are designed to allow humans to communicate instructions to machines.

The term computer language is sometimes used interchangeably with "programming language". However, usage of these terms varies among authors.

In one usage, programming languages are described as a subset of computer languages. Similarly, the term "computer language" may be used in contrast to the term "programming language" to describe languages used in computing but not considered programming languages – for example, markup languages. Some authors restrict the term "programming language" to Turing complete languages. Most practical programming languages are Turing complete, and as such are equivalent in what programs they can compute.

Another usage regards programming languages as theoretical constructs for programming abstract machines and computer languages as the subset thereof that runs on physical computers, which have finite hardware resources. John C. Reynolds emphasizes that formal specification languages are just as much programming languages as are the languages intended for execution. He also argues that textual and even graphical input formats that affect the behavior of a computer are programming languages, despite the fact they are commonly not Turing-complete, and remarks that ignorance of programming language concepts is the reason for many flaws in input formats.

History

Early developments

The first programmable computers were invented at the end of the 1940s, and with them, the first programming languages. The earliest computers were programmed in first-generation programming languages (1GLs), machine language (simple instructions that could be directly executed by the processor). This code was very difficult to debug and was not portable between different computer systems. In order to improve the ease of programming, assembly languages (or second-generation programming languages—2GLs) were invented, diverging from the machine language to make programs easier to understand for humans, although they did not increase portability.

Initially, hardware resources were scarce and expensive, while human resources were cheaper. Therefore, cumbersome languages that were time-consuming to use, but were closer to the hardware for higher efficiency were favored. The introduction of high-level programming languages (third-generation programming languages—3GLs)—revolutionized programming. These languages abstracted away the details of the hardware, instead being designed to express algorithms that could be understood more easily by humans. For example, arithmetic expressions could now be written in symbolic notation and later translated into machine code that the hardware could execute. In 1957, Fortran (FORmula TRANslation) was invented. Often considered the first compiled high-level programming language, Fortran has remained in use into the twenty-first century.

1960s and 1970s

Around 1960, the first mainframes—general purpose computers—were developed, although they could only be operated by professionals and the cost was extreme. The data and instructions were input by punch cards, meaning that no input could be added while the program was running. The languages developed at this time therefore are designed for minimal interaction. After the invention of the microprocessor, computers in the 1970s became dramatically cheaper. New computers also allowed more user interaction, which was supported by newer programming languages.

Lisp, implemented in 1958, was the first functional programming language. Unlike Fortran, it supported recursion and conditional expressions, and it also introduced dynamic memory management on a heap and automatic garbage collection. For the next decades, Lisp dominated artificial intelligence applications. In 1978, another functional language, ML, introduced inferred types and polymorphic parameters.

After ALGOL (ALGOrithmic Language) was released in 1958 and 1960, it became the standard in computing literature for describing algorithms. Although its commercial success was limited, most popular imperative languages—including C, Pascal, Ada, C++, Java, and C#—are directly or indirectly descended from ALGOL 60. Among its innovations adopted by later programming languages included greater portability and the first use of context-free, BNF grammar. Simula, the first language to support object-oriented programming (including subtypes, dynamic dispatch, and inheritance), also descends from ALGOL and achieved commercial success. C, another ALGOL descendant, has sustained popularity into the twenty-first century. C allows access to lower-level machine operations more than other contemporary languages. Its power and efficiency, generated in part with flexible pointer operations, comes at the cost of making it more difficult to write correct code.

Prolog, designed in 1972, was the first logic programming language, communicating with a computer using formal logic notation. With logic programming, the programmer specifies a desired result and allows the interpreter to decide how to achieve it.

1980s to 2000s

During the 1980s, the invention of the personal computer transformed the roles for which programming languages were used. New languages introduced in the 1980s included C++, a superset of C that can compile C programs but also supports classes and inheritance. Ada and other new languages introduced support for concurrency. The Japanese government invested heavily into the so-called fifth-generation languages that added support for concurrency to logic programming constructs, but these languages were outperformed by other concurrency-supporting languages.

Due to the rapid growth of the Internet and the World Wide Web in the 1990s, new programming languages were introduced to support Web pages and networking. Java, based on C++ and designed for increased portability across systems and security, enjoyed large-scale success because these features are essential for many Internet applications. Another development was that of dynamically typed scripting languages—Python, JavaScript, PHP, and Ruby—designed to quickly produce small programs that coordinate existing applications. Due to their integration with HTML, they have also been used for building web pages hosted on servers.

2000s to present

During the 2000s, there was a slowdown in the development of new programming languages that achieved widespread popularity. One innovation was service-oriented programming, designed to exploit distributed systems whose components are connected by a network. Services are similar to objects in object-oriented programming, but run on a separate process. C# and F# cross-pollinated ideas between imperative and functional programming. After 2010, several new languages—Rust, Go, Swift, Zig and Carbon —competed for the performance-critical software for which C had historically been used. Most of the new programming languages uses static typing while a few numbers of new languages use dynamic typing like Ring and Julia.

Some of the new programming languages are classified as visual programming languages like Scratch, LabVIEW and PWCT. Also, some of these languages mix between textual and visual programming usage like Ballerina. Also, this trend lead to developing projects that help in developing new VPLs like Blockly by Google. Many game engines like Unreal and Unity added support for visual scripting too.

Elements

Every programming language includes fundamental elements for describing data and the operations or transformations applied to them, such as adding two numbers or selecting an item from a collection. These elements are governed by syntactic and semantic rules that define their structure and meaning, respectively.

Syntax

Main article: Syntax (programming languages)

A programming language's surface form is known as its syntax. Most programming languages are purely textual; they use sequences of text including words, numbers, and punctuation, much like written natural languages. On the other hand, some programming languages are graphical, using visual relationships between symbols to specify a program.

The syntax of a language describes the possible combinations of symbols that form a syntactically correct program. The meaning given to a combination of symbols is handled by semantics (either formal or hard-coded in a reference implementation). Since most languages are textual, this article discusses textual syntax.

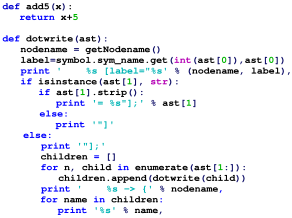

The programming language syntax is usually defined using a combination of regular expressions (for lexical structure) and Backus–Naur form (for grammatical structure). Below is a simple grammar, based on Lisp:

expression ::= atom | list

atom ::= number | symbol

number ::= ?+

symbol ::= .*

list ::= '(' expression* ')'

This grammar specifies the following:

- an expression is either an atom or a list;

- an atom is either a number or a symbol;

- a number is an unbroken sequence of one or more decimal digits, optionally preceded by a plus or minus sign;

- a symbol is a letter followed by zero or more of any alphabetical characters (excluding whitespace); and

- a list is a matched pair of parentheses, with zero or more expressions inside it.

The following are examples of well-formed token sequences in this grammar: 12345, () and (a b c232 (1)).

Not all syntactically correct programs are semantically correct. Many syntactically correct programs are nonetheless ill-formed, per the language's rules; and may (depending on the language specification and the soundness of the implementation) result in an error on translation or execution. In some cases, such programs may exhibit undefined behavior. Even when a program is well-defined within a language, it may still have a meaning that is not intended by the person who wrote it.

Using natural language as an example, it may not be possible to assign a meaning to a grammatically correct sentence or the sentence may be false:

- "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously." is grammatically well-formed but has no generally accepted meaning.

- "John is a married bachelor." is grammatically well-formed but expresses a meaning that cannot be true.

The following C language fragment is syntactically correct, but performs operations that are not semantically defined (the operation *p >> 4 has no meaning for a value having a complex type and p->im is not defined because the value of p is the null pointer):

complex *p = NULL; complex abs_p = sqrt(*p >> 4 + p->im);

If the type declaration on the first line were omitted, the program would trigger an error on the undefined variable p during compilation. However, the program would still be syntactically correct since type declarations provide only semantic information.

The grammar needed to specify a programming language can be classified by its position in the Chomsky hierarchy. The syntax of most programming languages can be specified using a Type-2 grammar, i.e., they are context-free grammars. Some languages, including Perl and Lisp, contain constructs that allow execution during the parsing phase. Languages that have constructs that allow the programmer to alter the behavior of the parser make syntax analysis an undecidable problem, and generally blur the distinction between parsing and execution. In contrast to Lisp's macro system and Perl's BEGIN blocks, which may contain general computations, C macros are merely string replacements and do not require code execution.

Semantics

| Logical connectives | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related concepts | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Applications | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The term semantics refers to the meaning of languages, as opposed to their form (syntax).

Static semantics

Static semantics defines restrictions on the structure of valid texts that are hard or impossible to express in standard syntactic formalisms. For compiled languages, static semantics essentially include those semantic rules that can be checked at compile time. Examples include checking that every identifier is declared before it is used (in languages that require such declarations) or that the labels on the arms of a case statement are distinct. Many important restrictions of this type, like checking that identifiers are used in the appropriate context (e.g. not adding an integer to a function name), or that subroutine calls have the appropriate number and type of arguments, can be enforced by defining them as rules in a logic called a type system. Other forms of static analyses like data flow analysis may also be part of static semantics. Programming languages such as Java and C# have definite assignment analysis, a form of data flow analysis, as part of their respective static semantics.

Dynamic semantics

Main article: Semantics of programming languages| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Programming language" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Once data has been specified, the machine must be instructed to perform operations on the data. For example, the semantics may define the strategy by which expressions are evaluated to values, or the manner in which control structures conditionally execute statements. The dynamic semantics (also known as execution semantics) of a language defines how and when the various constructs of a language should produce a program behavior. There are many ways of defining execution semantics. Natural language is often used to specify the execution semantics of languages commonly used in practice. A significant amount of academic research goes into formal semantics of programming languages, which allows execution semantics to be specified in a formal manner. Results from this field of research have seen limited application to programming language design and implementation outside academia.

Type system

Main articles: Data type, Type system, and Type safetyA data type is a set of allowable values and operations that can be performed on these values. Each programming language's type system defines which data types exist, the type of an expression, and how type equivalence and type compatibility function in the language.

According to type theory, a language is fully typed if the specification of every operation defines types of data to which the operation is applicable. In contrast, an untyped language, such as most assembly languages, allows any operation to be performed on any data, generally sequences of bits of various lengths. In practice, while few languages are fully typed, most offer a degree of typing.

Because different types (such as integers and floats) represent values differently, unexpected results will occur if one type is used when another is expected. Type checking will flag this error, usually at compile time (runtime type checking is more costly). With strong typing, type errors can always be detected unless variables are explicitly cast to a different type. Weak typing occurs when languages allow implicit casting—for example, to enable operations between variables of different types without the programmer making an explicit type conversion. The more cases in which this type coercion is allowed, the fewer type errors can be detected.

Commonly supported types

See also: Primitive data typeEarly programming languages often supported only built-in, numeric types such as the integer (signed and unsigned) and floating point (to support operations on real numbers that are not integers). Most programming languages support multiple sizes of floats (often called float and double) and integers depending on the size and precision required by the programmer. Storing an integer in a type that is too small to represent it leads to integer overflow. The most common way of representing negative numbers with signed types is twos complement, although ones complement is also used. Other common types include Boolean—which is either true or false—and character—traditionally one byte, sufficient to represent all ASCII characters.

Arrays are a data type whose elements, in many languages, must consist of a single type of fixed length. Other languages define arrays as references to data stored elsewhere and support elements of varying types. Depending on the programming language, sequences of multiple characters, called strings, may be supported as arrays of characters or their own primitive type. Strings may be of fixed or variable length, which enables greater flexibility at the cost of increased storage space and more complexity. Other data types that may be supported include lists, associative (unordered) arrays accessed via keys, records in which data is mapped to names in an ordered structure, and tuples—similar to records but without names for data fields. Pointers store memory addresses, typically referencing locations on the heap where other data is stored.

The simplest user-defined type is an ordinal type whose values can be mapped onto the set of positive integers. Since the mid-1980s, most programming languages also support abstract data types, in which the representation of the data and operations are hidden from the user, who can only access an interface. The benefits of data abstraction can include increased reliability, reduced complexity, less potential for name collision, and allowing the underlying data structure to be changed without the client needing to alter its code.

Static and dynamic typing

In static typing, all expressions have their types determined before a program executes, typically at compile-time. Most widely used, statically typed programming languages require the types of variables to be specified explicitly. In some languages, types are implicit; one form of this is when the compiler can infer types based on context. The downside of implicit typing is the potential for errors to go undetected. Complete type inference has traditionally been associated with functional languages such as Haskell and ML.

With dynamic typing, the type is not attached to the variable but only the value encoded in it. A single variable can be reused for a value of a different type. Although this provides more flexibility to the programmer, it is at the cost of lower reliability and less ability for the programming language to check for errors. Some languages allow variables of a union type to which any type of value can be assigned, in an exception to their usual static typing rules.

Concurrency

See also: Concurrent computingIn computing, multiple instructions can be executed simultaneously. Many programming languages support instruction-level and subprogram-level concurrency. By the twenty-first century, additional processing power on computers was increasingly coming from the use of additional processors, which requires programmers to design software that makes use of multiple processors simultaneously to achieve improved performance. Interpreted languages such as Python and Ruby do not support the concurrent use of multiple processors. Other programming languages do support managing data shared between different threads by controlling the order of execution of key instructions via the use of semaphores, controlling access to shared data via monitor, or enabling message passing between threads.

Exception handling

Main article: Exception handlingMany programming languages include exception handlers, a section of code triggered by runtime errors that can deal with them in two main ways:

- Termination: shutting down and handing over control to the operating system. This option is considered the simplest.

- Resumption: resuming the program near where the exception occurred. This can trigger a repeat of the exception, unless the exception handler is able to modify values to prevent the exception from reoccurring.

Some programming languages support dedicating a block of code to run regardless of whether an exception occurs before the code is reached; this is called finalization.

There is a tradeoff between increased ability to handle exceptions and reduced performance. For example, even though array index errors are common C does not check them for performance reasons. Although programmers can write code to catch user-defined exceptions, this can clutter a program. Standard libraries in some languages, such as C, use their return values to indicate an exception. Some languages and their compilers have the option of turning on and off error handling capability, either temporarily or permanently.

Design and implementation

Main article: Programming language design and implementationOne of the most important influences on programming language design has been computer architecture. Imperative languages, the most commonly used type, were designed to perform well on von Neumann architecture, the most common computer architecture. In von Neumann architecture, the memory stores both data and instructions, while the CPU that performs instructions on data is separate, and data must be piped back and forth to the CPU. The central elements in these languages are variables, assignment, and iteration, which is more efficient than recursion on these machines.

Many programming languages have been designed from scratch, altered to meet new needs, and combined with other languages. Many have eventually fallen into disuse. The birth of programming languages in the 1950s was stimulated by the desire to make a universal programming language suitable for all machines and uses, avoiding the need to write code for different computers. By the early 1960s, the idea of a universal language was rejected due to the differing requirements of the variety of purposes for which code was written.

Tradeoffs

Desirable qualities of programming languages include readability, writability, and reliability. These features can reduce the cost of training programmers in a language, the amount of time needed to write and maintain programs in the language, the cost of compiling the code, and increase runtime performance.

- Although early programming languages often prioritized efficiency over readability, the latter has grown in importance since the 1970s. Having multiple operations to achieve the same result can be detrimental to readability, as is overloading operators, so that the same operator can have multiple meanings. Another feature important to readability is orthogonality, limiting the number of constructs that a programmer has to learn. A syntax structure that is easily understood and special words that are immediately obvious also supports readability.

- Writability is the ease of use for writing code to solve the desired problem. Along with the same features essential for readability, abstraction—interfaces that enable hiding details from the client—and expressivity—enabling more concise programs—additionally help the programmer write code. The earliest programming languages were tied very closely to the underlying hardware of the computer, but over time support for abstraction has increased, allowing programmers express ideas that are more remote from simple translation into underlying hardware instructions. Because programmers are less tied to the complexity of the computer, their programs can do more computing with less effort from the programmer. Most programming languages come with a standard library of commonly used functions.

- Reliability means that a program performs as specified in a wide range of circumstances. Type checking, exception handling, and restricted aliasing (multiple variable names accessing the same region of memory) all can improve a program's reliability.

Programming language design often involves tradeoffs. For example, features to improve reliability typically come at the cost of performance. Increased expressivity due to a large number of operators makes writing code easier but comes at the cost of readability.

Natural-language programming has been proposed as a way to eliminate the need for a specialized language for programming. However, this goal remains distant and its benefits are open to debate. Edsger W. Dijkstra took the position that the use of a formal language is essential to prevent the introduction of meaningless constructs. Alan Perlis was similarly dismissive of the idea.

Specification

Main article: Programming language specificationThe specification of a programming language is an artifact that the language users and the implementors can use to agree upon whether a piece of source code is a valid program in that language, and if so what its behavior shall be.

A programming language specification can take several forms, including the following:

- An explicit definition of the syntax, static semantics, and execution semantics of the language. While syntax is commonly specified using a formal grammar, semantic definitions may be written in natural language (e.g., as in the C language), or a formal semantics (e.g., as in Standard ML and Scheme specifications).

- A description of the behavior of a translator for the language (e.g., the C++ and Fortran specifications). The syntax and semantics of the language have to be inferred from this description, which may be written in natural or formal language.

- A reference or model implementation, sometimes written in the language being specified (e.g., Prolog or ANSI REXX). The syntax and semantics of the language are explicit in the behavior of the reference implementation.

Implementation

Main article: Programming language implementationAn implementation of a programming language is the conversion of a program into machine code that can be executed by the hardware. The machine code then can be executed with the help of the operating system. The most common form of interpretation in production code is by a compiler, which translates the source code via an intermediate-level language into machine code, known as an executable. Once the program is compiled, it will run more quickly than with other implementation methods. Some compilers are able to provide further optimization to reduce memory or computation usage when the executable runs, but increasing compilation time.

Another implementation method is to run the program with an interpreter, which translates each line of software into machine code just before it executes. Although it can make debugging easier, the downside of interpretation is that it runs 10 to 100 times slower than a compiled executable. Hybrid interpretation methods provide some of the benefits of compilation and some of the benefits of interpretation via partial compilation. One form this takes is just-in-time compilation, in which the software is compiled ahead of time into an intermediate language, and then into machine code immediately before execution.

Proprietary languages

Although most of the most commonly used programming languages have fully open specifications and implementations, many programming languages exist only as proprietary programming languages with the implementation available only from a single vendor, which may claim that such a proprietary language is their intellectual property. Proprietary programming languages are commonly domain-specific languages or internal scripting languages for a single product; some proprietary languages are used only internally within a vendor, while others are available to external users.

Some programming languages exist on the border between proprietary and open; for example, Oracle Corporation asserts proprietary rights to some aspects of the Java programming language, and Microsoft's C# programming language, which has open implementations of most parts of the system, also has Common Language Runtime (CLR) as a closed environment.

Many proprietary languages are widely used, in spite of their proprietary nature; examples include MATLAB, VBScript, and Wolfram Language. Some languages may make the transition from closed to open; for example, Erlang was originally Ericsson's internal programming language.

Open source programming languages are particularly helpful for open science applications, enhancing the capacity for replication and code sharing.

Use

Thousands of different programming languages have been created, mainly in the computing field. Individual software projects commonly use five programming languages or more.

Programming languages differ from most other forms of human expression in that they require a greater degree of precision and completeness. When using a natural language to communicate with other people, human authors and speakers can be ambiguous and make small errors, and still expect their intent to be understood. However, figuratively speaking, computers "do exactly what they are told to do", and cannot "understand" what code the programmer intended to write. The combination of the language definition, a program, and the program's inputs must fully specify the external behavior that occurs when the program is executed, within the domain of control of that program. On the other hand, ideas about an algorithm can be communicated to humans without the precision required for execution by using pseudocode, which interleaves natural language with code written in a programming language.

A programming language provides a structured mechanism for defining pieces of data, and the operations or transformations that may be carried out automatically on that data. A programmer uses the abstractions present in the language to represent the concepts involved in a computation. These concepts are represented as a collection of the simplest elements available (called primitives). Programming is the process by which programmers combine these primitives to compose new programs, or adapt existing ones to new uses or a changing environment.

Programs for a computer might be executed in a batch process without human interaction, or a user might type commands in an interactive session of an interpreter. In this case the "commands" are simply programs, whose execution is chained together. When a language can run its commands through an interpreter (such as a Unix shell or other command-line interface), without compiling, it is called a scripting language.

Measuring language usage

Determining which is the most widely used programming language is difficult since the definition of usage varies by context. One language may occupy the greater number of programmer hours, a different one has more lines of code, and a third may consume the most CPU time. Some languages are very popular for particular kinds of applications. For example, COBOL is still strong in the corporate data center, often on large mainframes; Fortran in scientific and engineering applications; Ada in aerospace, transportation, military, real-time, and embedded applications; and C in embedded applications and operating systems. Other languages are regularly used to write many different kinds of applications.

Various methods of measuring language popularity, each subject to a different bias over what is measured, have been proposed:

- counting the number of job advertisements that mention the language

- the number of books sold that teach or describe the language

- estimates of the number of existing lines of code written in the language – which may underestimate languages not often found in public searches

- counts of language references (i.e., to the name of the language) found using a web search engine.

Combining and averaging information from various internet sites, stackify.com reported the ten most popular programming languages (in descending order by overall popularity): Java, C, C++, Python, C#, JavaScript, VB .NET, R, PHP, and MATLAB.

As of June 2024, the top five programming languages as measured by TIOBE index are Python, C++, C, Java and C#. TIOBE provide a list of top 100 programming languages according to popularity and update this list every month.

Dialects, flavors and implementations

A dialect of a programming language or a data exchange language is a (relatively small) variation or extension of the language that does not change its intrinsic nature. With languages such as Scheme and Forth, standards may be considered insufficient, inadequate, or illegitimate by implementors, so often they will deviate from the standard, making a new dialect. In other cases, a dialect is created for use in a domain-specific language, often a subset. In the Lisp world, most languages that use basic S-expression syntax and Lisp-like semantics are considered Lisp dialects, although they vary wildly as do, say, Racket and Clojure. As it is common for one language to have several dialects, it can become quite difficult for an inexperienced programmer to find the right documentation. The BASIC language has many dialects.

Classifications

Further information: Categorical list of programming languagesProgramming languages are often placed into four main categories: imperative, functional, logic, and object oriented.

- Imperative languages are designed to implement an algorithm in a specified order; they include visual programming languages such as .NET for generating graphical user interfaces. Scripting languages, which are partly or fully interpreted rather than compiled, are sometimes considered a separate category but meet the definition of imperative languages.

- Functional programming languages work by successively applying functions to the given parameters. Although appreciated by many researchers for their simplicity and elegance, problems with efficiency have prevented them from being widely adopted.

- Logic languages are designed so that the software, rather than the programmer, decides what order in which the instructions are executed.

- Object-oriented programming—whose characteristic features are data abstraction, inheritance, and dynamic dispatch—is supported by most popular imperative languages and some functional languages.

Although markup languages are not programming languages, some have extensions that support limited programming. Additionally, there are special-purpose languages that are not easily compared to other programming languages.

See also

- Comparison of programming languages (basic instructions)

- Comparison of programming languages

- Computer programming

- Computer science and Outline of computer science

- Domain-specific language

- Domain-specific modeling

- Educational programming language

- Esoteric programming language

- Extensible programming

- Category:Extensible syntax programming languages

- Invariant-based programming

- List of BASIC dialects

- Lists of programming languages

- List of programming language researchers

- Programming languages used in most popular websites

- Language-oriented programming

- Logic programming

- Literate programming

- Metaprogramming

- Modeling language

- Programming language theory

- Pseudocode

- Rebol § Dialects

- Reflective programming

- Scientific programming language

- Scripting language

- Software engineering and List of software engineering topics

References

- ^ Aaby, Anthony (2004). Introduction to Programming Languages. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Robert A. Edmunds, The Prentice-Hall standard glossary of computer terminology, Prentice-Hall, 1985, p. 91

- Pascal Lando, Anne Lapujade, Gilles Kassel, and Frédéric Fürst, Towards a General Ontology of Computer Programs Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ICSOFT 2007 Archived 27 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 163–170

- XML in 10 points Archived 6 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine W3C, 1999, "XML is not a programming language."

- Powell, Thomas (2003). HTML & XHTML: the complete reference. McGraw-Hill. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-07-222942-4.

HTML is not a programming language.

- Dykes, Lucinda; Tittel, Ed (2005). XML For Dummies (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7645-8845-7.

...it's a markup language, not a programming language.

- In mathematical terms, this means the programming language is Turing-complete MacLennan, Bruce J. (1987). Principles of Programming Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-511306-8.

- "Turing Completeness". www.cs.odu.edu. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- R. Narasimhan, Programming Languages and Computers: A Unified Metatheory, pp. 189—247 in Franz Alt, Morris Rubinoff (eds.) Advances in computers, Volume 8, Academic Press, 1994, ISBN 0-12-012108-5, p.215: " the model for computer languages differs from that for programming languages in only two respects. In a computer language, there are only finitely many names—or registers—which can assume only finitely many values—or states—and these states are not further distinguished in terms of any other attributes. This may sound like a truism but its implications are far-reaching. For example, it would imply that any model for programming languages, by fixing certain of its parameters or features, should be reducible in a natural way to a model for computer languages."

- John C. Reynolds, "Some thoughts on teaching programming and programming languages", SIGPLAN Notices, Volume 43, Issue 11, November 2008, p.109

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 519.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 521.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 522.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 42.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 524.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 42–44.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 523–524.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 527.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 528.

- "How Lisp Became God's Own Programming Language". twobithistory.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 47–48.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 526.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 50.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 701–703.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 524–525.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 56–57.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 525.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 526–527.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 531.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 79.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 530.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 532–533.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 534.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 534–535.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 535.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 736.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 536.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 536–537.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 91–92.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 538–539.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 97–99.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 542.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 474–475, 477, 542.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 542–543.

- Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 544.

- Bezanson, J., Karpinski, S., Shah, V.B. and Edelman, A., 2012. Julia: A fast dynamic language for technical computing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1209.5145.

- Ayouni, M. and Ayouni, M., 2020. Data Types in Ring. Beginning Ring Programming: From Novice to Professional, pp.51-98.

- Sáez-López, J.M., Román-González, M. and Vázquez-Cano, E., 2016. Visual programming languages integrated across the curriculum in elementary school: A two year case study using “Scratch” in five schools. Computers & Education, 97, pp.129-141.

- Fayed, M.S., Al-Qurishi, M., Alamri, A. and Al-Daraiseh, A.A., 2017, March. PWCT: visual language for IoT and cloud computing applications and systems. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Internet of things, Data and Cloud Computing (pp. 1-5).

- Kodosky, J., 2020. LabVIEW. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages, 4(HOPL), pp.1-54.

- Fernando, A. and Warusawithana, L., 2020. Beginning Ballerina Programming: From Novice to Professional. Apress.

- Baluprithviraj, K.N., Bharathi, K.R., Chendhuran, S. and Lokeshwaran, P., 2021, March. Artificial intelligence based smart door with face mask detection. In 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems (ICAIS) (pp. 543-548). IEEE.

- Sewell, B., 2015. Blueprints visual scripting for unreal engine. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- Bertolini, L., 2018. Hands-On Game Development without Coding: Create 2D and 3D games with Visual Scripting in Unity. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- Michael Sipser (1996). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 978-0-534-94728-6. Section 2.2: Pushdown Automata, pp.101–114.

- Jeffrey Kegler, "Perl and Undecidability Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine", The Perl Review. Papers 2 and 3 prove, using respectively Rice's theorem and direct reduction to the halting problem, that the parsing of Perl programs is in general undecidable.

- Marty Hall, 1995, Lecture Notes: Macros Archived 6 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, PostScript version Archived 17 August 2000 at the Wayback Machine

- Michael Lee Scott, Programming language pragmatics, Edition 2, Morgan Kaufmann, 2006, ISBN 0-12-633951-1, p. 18–19

- ^ Winskel, Glynn (5 February 1993). The Formal Semantics of Programming Languages: An Introduction. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73103-4.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 244.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 245.

- ^ Andrew Cooke. "Introduction To Computer Languages". Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 15, 408–409.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 303–304.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 246–247.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 249.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 260.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 250.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 254.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 281–282.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 272–273.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 276–277.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 280.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 289–290.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 255.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 244–245.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 477.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 211.

- Leivant, Daniel (1983). Polymorphic type inference. ACM SIGACT-SIGPLAN symposium on Principles of programming languages. Austin, Texas: ACM Press. pp. 88–98. doi:10.1145/567067.567077. ISBN 978-0-89791-090-3.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 212–213.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 284–285.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 576.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 579.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 585.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 585–586.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 630, 634.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 635.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 631.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 261.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 632.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 631, 635–636.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 18.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 19.

- Nofre, Priestley & Alberts 2014, p. 55.

- Nofre, Priestley & Alberts 2014, p. 60.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 8.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 16–17.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 8–9.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 9–10.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 12–13.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 13.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 14–15.

- Frederick P. Brooks, Jr.: The Mythical Man-Month, Addison-Wesley, 1982, pp. 93–94

- Busbee, Kenneth Leroy; Braunschweig, Dave (15 December 2018). "Standard Libraries". Programming Fundamentals – A Modular Structured Approach. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 15.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 8, 16.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 18, 23.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 23.

- Dijkstra, Edsger W. On the foolishness of "natural language programming." Archived 20 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine EWD667.

- Perlis, Alan (September 1982). "Epigrams on Programming". SIGPLAN Notices Vol. 17, No. 9. pp. 7–13. Archived from the original on 17 January 1999.

- Milner, R.; M. Tofte; R. Harper; D. MacQueen (1997). The Definition of Standard ML (Revised). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63181-5.

- Kelsey, Richard; William Clinger; Jonathan Rees (February 1998). "Section 7.2 Formal semantics". Revised Report on the Algorithmic Language Scheme. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006.

- ANSI – Programming Language Rexx, X3-274.1996

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 23–24.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 25–27.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 27.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 28.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 29–30.

- See: Oracle America, Inc. v. Google, Inc.

- "Guide to Programming Languages | ComputerScience.org". ComputerScience.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "The basics". ibm.com. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Abdelaziz, Abdullah I.; Hanson, Kent A.; Gaber, Charles E.; Lee, Todd A. (2023). "Optimizing large real-world data analysis with parquet files in R: A step-by-step tutorial". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 33 (3): e5728. doi:10.1002/pds.5728. PMID 37984998.

- "HOPL: an interactive Roster of Programming Languages". Australia: Murdoch University. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

This site lists 8512 languages.

- Mayer, Philip; Bauer, Alexander (2015). "An empirical analysis of the utilization of multiple programming languages in open source projects". Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering – EASE '15. New York, NY, US: ACM. pp. 4:1–4:10. doi:10.1145/2745802.2745805. ISBN 978-1-4503-3350-4.

Results: We found (a) a mean number of 5 languages per project with a clearly dominant main general-purpose language and 5 often-used DSL types, (b) a significant influence of the size, number of commits, and the main language on the number of languages as well as no significant influence of age and number of contributors, and (c) three language ecosystems grouped around XML, Shell/Make, and HTML/CSS. Conclusions: Multi-language programming seems to be common in open-source projects and is a factor that must be dealt with in tooling and when assessing the development and maintenance of such software systems.

- Abelson, Sussman, and Sussman. "Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vicki, Brown; Morin, Rich (1999). "Scripting Languages". MacTech. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017.

- Georgina Swan (21 September 2009). "COBOL turns 50". Computerworld. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Ed Airey (3 May 2012). "7 Myths of COBOL Debunked". developer.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Nicholas Enticknap. "SSL/Computer Weekly IT salary survey: finance boom drives IT job growth". Computer Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Counting programming languages by book sales". Radar.oreilly.com. 2 August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- Bieman, J.M.; Murdock, V., Finding code on the World Wide Web: a preliminary investigation, Proceedings First IEEE International Workshop on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation, 2001

- "Most Popular and Influential Programming Languages of 2018". stackify.com. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "TIOBE Index". Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 21–22.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 12.

- Sebesta 2012, p. 22.

- Sebesta 2012, pp. 22–23.

Further reading

See also: History of programming languages § Further reading- Abelson, Harold; Sussman, Gerald Jay (1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (2nd ed.). MIT Press. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

- Raphael Finkel: Advanced Programming Language Design, Addison Wesley 1995.

- Daniel P. Friedman, Mitchell Wand, Christopher T. Haynes: Essentials of Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2001.

- David Gelernter, Suresh Jagannathan: Programming Linguistics, The MIT Press 1990.

- Ellis Horowitz (ed.): Programming Languages, a Grand Tour (3rd ed.), 1987.

- Ellis Horowitz: Fundamentals of Programming Languages, 1989.

- Shriram Krishnamurthi: Programming Languages: Application and Interpretation, online publication Archived 30 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gabbrielli, Maurizio; Martini, Simone (2023). Programming Languages: Principles and Paradigms (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-34144-1.

- Bruce J. MacLennan: Principles of Programming Languages: Design, Evaluation, and Implementation, Oxford University Press 1999.

- John C. Mitchell: Concepts in Programming Languages, Cambridge University Press 2002.

- Nofre, David; Priestley, Mark; Alberts, Gerard (2014). "When Technology Became Language: The Origins of the Linguistic Conception of Computer Programming, 1950–1960". Technology and Culture. 55 (1): 40–75. doi:10.1353/tech.2014.0031. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 24468397. PMID 24988794.

- Benjamin C. Pierce: Types and Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2002.

- Terrence W. Pratt and Marvin Victor Zelkowitz: Programming Languages: Design and Implementation (4th ed.), Prentice Hall 2000.

- Peter H. Salus. Handbook of Programming Languages (4 vols.). Macmillan 1998.

- Ravi Sethi: Programming Languages: Concepts and Constructs, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley 1996.

- Michael L. Scott: Programming Language Pragmatics, Morgan Kaufmann Publishers 2005.

- Sebesta, Robert W. (2012). Concepts of Programming Languages (10 ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-13-139531-2.

- Franklyn Turbak and David Gifford with Mark Sheldon: Design Concepts in Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2009.

- Peter Van Roy and Seif Haridi. Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming, The MIT Press 2004.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Concepts and Paradigms. Prentice Hall 1990.

- David A. Watt and Muffy Thomas. Programming Language Syntax and Semantics. Prentice Hall 1991.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Processors. Prentice Hall 1993.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Design Concepts. John Wiley & Sons 2004.

- Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

| Types of programming languages | |

|---|---|

| Level | |

| Generation | |

| Programming languages | |

|---|---|

| Types of computer language | |

|---|---|

| Types | |

| See also | |

Definitions from Wiktionary

Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons

Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks Resources from Wikiversity

Resources from Wikiversity Data from Wikidata

Data from Wikidata

,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,