| Revision as of 01:05, 19 December 2024 editSpino-Soar-Us (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,059 edits Translating French page of the Insular Japonic LanguagesTag: harv-error | Revision as of 09:49, 19 December 2024 edit undoSpino-Soar-Us (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,059 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Insular Japonic languages''' |

The '''Insular Japonic languages''' or '''Japonic-Ryukyu languages''' are a subdivision of the ], as opposed to the hypothetical ] languages formerly spoken in central and southern ]. This grouping, originally proposed by ], has been taken up several times subsequently.<ref>Vovin (2017)</ref> | ||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| Currently, most scholars agree that the Japonic languages were brought to the ] between the 7th and 3rd centuries BC by wet rice farmers of the ] from northern ], replacing the indigenous ].{{sfn|Serafim|2008|p=98}} Toponyms indicate that the ] were formerly spoken in eastern ].<ref>Patrie (1982), p. 4.</ref><ref>Tamura (2000), p. 269.</ref><ref>Hudson (1999), p. 98.</ref> Later, Japonic speakers settled on the ].{{sfn|Serafim|2008|p=98}} | Currently, most scholars agree that the Japonic languages were brought to the ] between the 7th and 3rd centuries BC by wet rice farmers of the ] from northern ], replacing the indigenous ].{{sfn|Serafim|2008|p=98}} Toponyms indicate that the ] were formerly spoken in eastern ].<ref>Patrie (1982), p. 4.</ref><ref>Tamura (2000), p. 269.</ref><ref>Hudson (1999), p. 98.</ref> Later, Japonic speakers settled on the ].{{sfn|Serafim|2008|p=98}} | ||

| Linguistically, there is disagreement over the location and date of separation from the continental branch. ] argues that the two branches of the "Japonic" (Japonic) family split when their speakers moved from ] around 1500 BC to |

Linguistically, there is disagreement over the location and date of separation from the continental branch. ] argues that the two branches of the "Japonic" (Japonic) family split when their speakers moved from ] around 1500 BC to central and southern Korea. According to her, the Insular Japonic languages entered the archipelago around 700 BC, with some remaining in the southern ] and ] confederations.{{sfn|Robbeets|Savelyev|2020|p=4}} This theory has little support. Vovin and Whitman instead argue that the Insular Japonic languages split from the Peninsular Japonic languages upon arriving in Kyūshū between 1000 and 800 BC.<ref>Whitman (2011), p.157</ref> | ||

| There is also disagreement regarding the separation of ] and the Ryukyu languages. One theory suggests that when taking into account innovations in Old Japanese not shared with the Ryukyu languages, the two branches must have separated before the 7th century,{{sfn|Pellard|2015|p=21-22}} with the ] |

There is also disagreement regarding the separation of ] and the Ryukyu languages. One theory suggests that when taking into account innovations in Old Japanese not shared with the Ryukyu languages, the two branches must have separated before the 7th century,{{sfn|Pellard|2015|p=21-22}} with the ] migrating from southern Kyushu to the Ryukyus with the expansion of the ] around the 10th–11th century.{{sfn|Pellard|2015|p=30-31}} Old Japanese is thought to have emerged during the ].<ref>Shibatani 1990, p. 119.</ref> Robbeets proposes a similar theory, but places the separation date in the 1st century BC.{{sfn|Robbeets|Savelyev|2020|p=6}} Boer proposes that the Ryukyu languages are descended from the Kyushuan dialect of Old Japanese.<ref name="x1">de Boer (2020), p. 52.</ref> One theory also suggests that Ryukyus remained in Kyushu until the 12th century.{{sfn|Pellard|2015}} | ||

| == Internal classification == | == Internal classification == | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| === Standard classification === | === Standard classification === | ||

| This classification below is the most widely used. Vovin classifies the ] as part of the Insular Japonic branch.<ref>Vovin (2013), pp. 236–237.</ref>{{,}}<ref>Vovin (2010), pp. 24–25.</ref> ], spoken in the ] and formerly in the ] |

This classification below is the most widely used. Vovin classifies the ] as part of the Insular Japonic branch.<ref>Vovin (2013), pp. 236–237.</ref>{{,}}<ref>Vovin (2010), pp. 24–25.</ref> ], spoken in the ] and formerly in the ] iss sometimes considered a separate language due to its divergence from modern Japanese.<ref>Iannucci (2019), pp. 100–120.</ref> Robbeets (2020) treats the ] and ] dialects as independent languages.{{sfn|Robbeets|Savelyev|2020|p=6}} Dialects are indicated in ''italics''. | ||

| {{tree list}} | {{tree list}} | ||

Revision as of 09:49, 19 December 2024

Branch of the Japonic languages| Insular Japonic | |

|---|---|

| Japonic-Ryukyu, Japonic proper | |

| Geographic distribution | Japan, Taiwan (Yilan) and formerly South Korea (Jeju Island) |

| Linguistic classification | Japonic

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

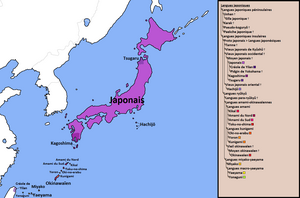

Map of the modern Japonic languages, including Insular Japonic languages. Map of the modern Japonic languages, including Insular Japonic languages. | |

The Insular Japonic languages or Japonic-Ryukyu languages are a subdivision of the Japonic languages, as opposed to the hypothetical Peninsular Japonic languages formerly spoken in central and southern Korea. This grouping, originally proposed by Vovin, has been taken up several times subsequently.

History

Currently, most scholars agree that the Japonic languages were brought to the Japanese archipelago between the 7th and 3rd centuries BC by wet rice farmers of the Yayoi culture from northern Kyushu, replacing the indigenous Jōmon people. Toponyms indicate that the Ainu language were formerly spoken in eastern Japan. Later, Japonic speakers settled on the Ryukyu Islands.

Linguistically, there is disagreement over the location and date of separation from the continental branch. Martine Robbeets argues that the two branches of the "Japonic" (Japonic) family split when their speakers moved from Shandong around 1500 BC to central and southern Korea. According to her, the Insular Japonic languages entered the archipelago around 700 BC, with some remaining in the southern Mahan and Byeonhan confederations. This theory has little support. Vovin and Whitman instead argue that the Insular Japonic languages split from the Peninsular Japonic languages upon arriving in Kyūshū between 1000 and 800 BC.

There is also disagreement regarding the separation of Old Japanese and the Ryukyu languages. One theory suggests that when taking into account innovations in Old Japanese not shared with the Ryukyu languages, the two branches must have separated before the 7th century, with the Ryukyus migrating from southern Kyushu to the Ryukyus with the expansion of the Gusuku culture around the 10th–11th century. Old Japanese is thought to have emerged during the Nara period. Robbeets proposes a similar theory, but places the separation date in the 1st century BC. Boer proposes that the Ryukyu languages are descended from the Kyushuan dialect of Old Japanese. One theory also suggests that Ryukyus remained in Kyushu until the 12th century.

Internal classification

The relationship between Japanese and the Ryukyu languages was established in the 19th century by Basil Hall Chamberlain in his comparison of Okinawan and Japanese.

Standard classification

This classification below is the most widely used. Vovin classifies the Tamna language as part of the Insular Japonic branch. · Hachijō, spoken in the Southern Izu Islands and formerly in the Daitō Islands iss sometimes considered a separate language due to its divergence from modern Japanese. Robbeets (2020) treats the Fukuoka and Kagoshima dialects as independent languages. Dialects are indicated in italics.

- Insular Japonic Languages

- Old Japanese †

- Tamna †

- Old Kyushu Japanese †

- Old Western Japanese †

- Eastern Old Japanese †

- Ryukyuan

- Northern Ryukyuan

- Amami

- Amami Ōshima

- Naze

- Sani

- Southern Amami Ōshima

- Kikai

- Onotsu

- Tokunoshima

- Amami Ōshima

- Kunigami

- Okinawan

- Kudaka

- Naha

- Shuri

- Torishima

- Amami

- Southern Ryukyuan

- Northern Ryukyuan

- Old Japanese †

Alternative classification

Another classification based on pitch accents has been proposed. According to this, Japanese is paraphyletic within Insular Japonic.

- Insular Japonic Languages

- Old Japanese

- Izu

- Hachijo/South Izu

- North Izu

- Kanto-Echigo

- Kanto

- Echigo

- Nagano-Yamanashi-Shizuoka

- Izu

- Old Central Japanese

- Ishikawa-Toyama

- Gifu-Aichi

- Kinki-Totsukawa

- Shikoku

- Chūgoku

- Izumo-Tohoku

- Conservative Izumo-Tohoku

- Shimokita/Eastern Iwate

- Peripheral Izumo

- Innovative Izumo-Tohoku

- Tohoku

- Central Izumo

- Conservative Izumo-Tohoku

- Kyushu-Ryukyu

- Northeastern Kyushu

- Southeastern Kyushu

- Southwestern Kyushu-Ryukyu

- Western Kyushu

- South Kyushu-Ryukyu

- South Kyushu

- Ryukyuan

- Old Japanese

Japanese - Ryukyu lexical comparison

The first ten letters of the alphabet according to this source..

| English | Insular Proto-Japonic | Old Japanese | Japanese | Hachijō | Proto-Ryukyuan | Okinawan | Miyakoan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | *pitə | pitötu | ichi | tetsu | *pito | tiːtɕi | pi̥tiitsɿ |

| two | *puta | putatu | ni | ɸu̥tatsu | *puta | taːtɕi | fu̥taatsɿ |

| three | *mi(t) | mitu | san | mittsu | *mi | miːtɕi | miitsɿ |

| four | *jə | yötu | shi, yon | jottsu | *yo | juːtɕi | juutsɿ |

| five | *itu, *etu | itutu | go | itsutsu | *etu | itɕitɕi | itsɿtsɿ |

| six | *mu(t) | mutu | roku | muttsu | *mu | muːtɕi | mmtsɿ |

| seven | *nana | nanatu | shichi, nana | nanatsu | *nana | nanatɕiː | nanatsɿ |

| eight | *ja | yatu | hachi | jattsu | *ya | jaːtɕi | jaatsɿ |

| nine | *kəkənə | kökönötu | ku, kyuu | kokonotsu | *kokono | kukunutɕi | ku̥kunutsɿ |

| ten | *təwə | tö | juu | tou | *towa | tuː | tuu |

References

- Vovin (2017)

- ^ Serafim 2008, p. 98. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSerafim2008 (help)

- Patrie (1982), p. 4.

- Tamura (2000), p. 269.

- Hudson (1999), p. 98.

- Robbeets & Savelyev 2020, p. 4.

- Whitman (2011), p.157

- Pellard 2015, p. 21-22. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPellard2015 (help)

- Pellard 2015, p. 30-31. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPellard2015 (help)

- Shibatani 1990, p. 119.

- ^ Robbeets & Savelyev 2020, p. 6.

- ^ de Boer (2020), p. 52.

- Pellard 2015. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPellard2015 (help)

- Basil Hall Chamberlain, Yokohama, Kelly & Walsh, coll. “Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan” ( no . 23, supplement), 1895.

- John Bentley, , dans Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara et Michinori Shimoji, , Berlin, De Mouton Gruyter, 2015 ISBN 9781614511618, DOI 10.1515/9781614511151.39), p. 39-60

- Vovin (2013), pp. 236–237.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 24–25.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 100–120.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 187, 189.

- Chien, Yuehchen; Sanada, Shinji (2010). "Yilan Creole in Taiwan". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 25 (2): 350–357. doi:10.1075/jpcl.25.2.11yue.

- ^ "Family: Japonic". Glottolog. Retrieved 2024-12-17.

- Pellard 2015, p. 18-20. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPellard2015 (help)

- Shimabukuro (2007), pp. 2, 41–43.

- "JAPONIC LANGUAGES" (in French). Retrieved 2024-12-16.

Bibliography

- Alexander Vovin (2017). Origins of the Japanese Language. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- Alexander Vovin (2013). From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean. Korean Linguistics. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- Alexander Vovin (2010). Korea-Japonica: A Re-Evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3278-0.

- Masayoshi Shibatani (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

- Elisabeth de Boer (2020). The classification of the Japonic languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880462-8. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- Robbeets, Martine; Savelyev, Alexander (2020). The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198804628.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-880462-8.

- James Patrie (1982). The Genetic Relationship of the Ainu Language, Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0724-5. JSTOR 20006692.

- Suzuko Tamura (2000). The Ainu Language. Tōkyō: ICHEL Linguistic Studies. ISBN 978-4-385-35976-2.

- Mark J. Hudson (1999). Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2156-2.

- David J. Iannucci (2019). The Hachijō Language of Japan: Phonology and Historical Development. Mānoa: University of Hawaiʻi.

- John Whitman (2011). Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan. Rice. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- Leon A. Serafim (2008), "The uses of Ryukyuan in understanding Japanese language history", in Bjarne Frellesvig; John Whitman (eds.), Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects, John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 79–99, ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1

- Elisabeth de Boer (2020), "The classification of the Japonic languages", in Martine Robbeets; Alexander Savelyev (eds.), The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages, Oxford University Press, p. 40–58

- Thomas Pellard (2015), "The linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu Islands", in Patrick Heinrich; Shinsho Miyara; Michinori Shimoji (eds.), Handbook of the Ryukyuan languages: History, structure, and use, De Gruyter Mouton, p. 13–37, doi:10.1515/9781614511151.13, ISBN 978-1-61451-161-8, S2CID 54004881.

| Japonic languages | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese |  | ||||||||||||

| Ryukyuan |

| ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| Languages of Japan | |

|---|---|

| National language | |

| Indigenous languages | |

| Non-Indigenous languages | |

| Creole languages | |

| Sign languages | |