| Revision as of 14:58, 30 May 2007 view sourceAngus Lepper (talk | contribs)Rollbackers4,154 editsm rvv← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:58, 30 May 2007 view source 216.11.202.122 (talk) →Awards and recognitionNext edit → | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

| == Awards and recognition== | == Awards and recognition== | ||

| worst player of the year | |||

| ], ], where a major street has the honorary name Jackie Robinson Way.]] | |||

| *According to a poll conducted by ] in ], Robinson was the second most popular man in the country, behind ]. <ref>http://www.fulton.k12.ga.us/teacher/stratton/robinson2.html</ref> | |||

| *In ], ] ] posthumously awarded Robinson the ]. | |||

| *In ], Major League Baseball renamed the Rookie of the Year Award the Jackie Robinson Award in his honor. | |||

| *On ], ], Jackie Robinson's #42 was retired by Major League Baseball, meaning that no future player on any major league team could wear it. Players wearing #42 at the time, some of whom said they did so as a tribute to Robinson, were allowed to continue wearing it, thereby ] the number's retirement. The only player currently wearing the number is ] closer ]. | |||

| *In ], he was named by ] on its ] of the 100 most influential people of the ].<ref></ref> | |||

| *In ], he ranked number 44 on '']'s'' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and was elected to the ]. | |||

| *On ], ], the ] posthumously awarded Robinson the ], the highest award the Congress can bestow. Robinson's widow accepted the award in a ceremony in the Capitol Rotunda on ], ]. | |||

| *At the ] ] groundbreaking for a new ] ballpark, ], scheduled to open in ], it was announced that the main entrance, modeled on the one in ]'s old ], will be called the Jackie Robinson Rotunda. Additionally, Mets owner ] said that the Mets and ] would work with the Jackie Robinson Foundation to create a Jackie Robinson Museum and Learning Center in lower ], as well as fund scholarships for "young people who live by and embody Jackie's ideals."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nydailynews.com/news/2006/11/14/2006-11-14_mets_honor_robinson_at_new_home.html |title= METS HONOR ROBINSON AT NEW HOME|publisher=]|date=]|accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> | |||

| ===60th anniversary tribute=== | |||

| On ], ], the 60th anniversary of Robinson's major league debut, Major League Baseball invited players to wear the number 42 just for that day to commemorate Robinson. The gesture was the idea of ] outfielder ], who first sought ] permission, and, after receiving it, asked Commissioner ] for permission. Selig extended the invitation to all major league teams.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://mlb.mlb.com/news/press_releases/press_release.jsp?ymd=20070404&content_id=1879309&vkey=pr_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb |title=Griffey, Jr., others to wear No. 42 as part of Jackie Robinson Day Tribute|publisher=]|date=]|accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> Ultimately, more than 200 players wore number 42, including the entire rosters of the ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/13/sports/baseball/13jackie.html?_r=1&ref=baseball&oref=slogin | |||

| |title= A Measure of Respect for Jackie Robinson Turns Into a Movement | |||

| |publisher=]|date=] | |||

| |accessdate=2007-04-15}}</ref> Considering that the Phillies and the Cardinals had probably inflicted the most abuse on Robinson when he came up to the major leagues, it was considered quite a tribute that their entire teams chose to wear his number to honor him. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:58, 30 May 2007

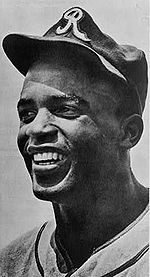

Jack Roosevelt "Jackie" Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) became the first African-American professional baseball player of the modern era in 1947. While not the first African American professional baseball player in history, his Major League debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers ended approximately eighty years of baseball segregation, also known as the baseball color line. The Baseball Hall of Fame inducted Robinson in 1962 and he was a member of six World Series teams. He earned six consecutive All-Star Game nominations and won several awards during his career. In 1947, Robinson won The Sporting News Rookie of the Year Award and the first Rookie of the Year Award Award. Two years later, he was awarded his first National League MVP Award. In addition to his accomplishments on the field, Jackie Robinson was also a forerunner of the Civil Rights Movement. He was a key figure in the establishment and growth of the Freedom Bank, an African-American owned and controlled entity, in the 1960s. He also wrote a syndicated newspaper column for a number of years, in which he was an outspoken supporter of Martin Luther King Jr. and, to a lesser degree, Malcolm X. Template:MLB HoF Robinson engaged in political campaigning for a number of politicians, including the Democrat Hubert Humphrey and the Republican Richard Nixon.

In recognition of his accomplishments, Robinson was posthumously awarded a Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

On April 15, 1997, the 50 year anniversary of his debut, Major League Baseball retired the number 42, the number Robinson wore, in recognition of his accomplishments both on and off the field. In 1950, he was the subject of a film biography, The Jackie Robinson Story, in which he played himself. He became a political activist in his post-playing days.

In 1946, Robinson married Rachel Annetta Isum. In 1973, after Jackie died, Rachel founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation.

Early life

In 1919, Jackie Robinson, the youngest of five children, was born in Cairo, Georgia during a Spanish flu and smallpox epidemic. In 1920, his family moved to Pasadena, California after his father abandoned them.

Robinson grew up in relative poverty and even joined a local neighborhood gang in his youth. Eventually, his friend Carl Anderson persuaded Robinson to abandon the gang.

In 1935, Robinson graduated from Dakota Junior High School and enrolled in John Muir High School ("Muir Tech"). There he played on various Muir Tech sport teams, and lettered in four of them. He was a shortstop and catcher on the baseball team, a quarterback on the football team, a guard on the basketball team, and a member of the tennis team and the track and field squad. He won awards in the broad jump.

In 1936, he captured the junior boys singles championship in the annual Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament, starred as quarterback, and earned a place on the annual Pomona baseball tournament all-star team, which included future Baseball Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Bob Lemon. The next year, Jackie played for the high school's basketball team. That year, the Pasadena Star-News newspaper reported on the young Robinson.

After leaving Muir, Jackie attended Pasadena Junior College and played both football and baseball. He played quarterback and safety for the football team, shortstop and leadoff batter for the baseball team, and participated in the broad jump.

While at PJC, he was elected to the "Lancers,” a student run police organization responsible for patrolling various school activities. He dated and made friends. However, on January 25, 1938, he was arrested for questionable reasons and sentenced to two years probation.

In 1938, he was elected to the All-Southland Junior College (baseball) Team and selected as the region's Most Valuable Player. On February 4, 1939, he played his last basketball game at Pasadena Junior College. Thereupon Robinson was awarded a gold pin and was named to the school's "Order of the Mast and Dagger.”

After leaving PJC, Robinson chose to attend the nearby University of California, Los Angeles, where became the school's first athlete to win varsity letters in four sports: baseball, basketball, football and track. Despite many athletic achievements and having nearly completed the requirements for his degree, he withdrew from the university for financial reasons in 1941. He then briefly worked as an athletic director for the National Youth Administration before going to Honolulu that fall to play football for the semi-professional, racially integrated Honolulu Bears. The season was brief, and he returned that December, shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that drew the United States into World War II. He was drafted the following year.

Military career

Jackie Robinson served in the United States Army from 1942-1944 as a second lieutenant, and his actions during his military service not only presaged his breaking of the color line in baseball, but may also have influenced, however indirectly, President Harry S. Truman’s decision to integrate U.S. Armed forces in 1948. As the finding aid to the Jackie Robinson Papers at the Library of Congress succinctly notes, the archive includes: "ersonnel records from Robinson's military service, including court-martial charges of insubordination resulting from his refusal to obey an order to move to the back of a segregated military bus in Texas. A military jury acquitted Robinson, and shortly thereafter, he received an honorable discharge.”

Jackie thus revealed himself to be a man of principle and courage years before he entered the public eye. His July 6, 1944 refusal to submit to Jim Crow laws while in the military pre-date, by more than a decade, a similar, but much more widely-known “stance” by Rosa Parks, who famously refused to give up her seat on a public bus in 1955. At his August 2, 1944 court martial, Jackie was found innocent of insubordination. He was honorably discharged from military duty on November 28, 1944, but his story, and his resistance to hatred rooted in bizarre notions spawned by scientific racism and popular prejudice had only really just begun.

The racism which poisoned baseball permeated all of American society. Jackie Robinson's remarkable courage, as expemplified by his early protest in the military long before his entry into a very popular and public sport, and his resolute stand for simple human decency must therefore be seen as profoundly important not only to professional sports, but to the entirety of American culture. As one historian has concisely noted: "Once the integretative or leveling model of baseball -- all America playing and working in harmony -- was extended to African Americans, the effect on the nation was profound. Eighty years after the Civil War, America had proved itself unable to practice the values for which it was fought."

Jackie's life, including the military court martial which cleared his name of insubordination for refusing to submit to the humiliation of segregation, may thus be seen as an early turning point in the life of the nation.

The Dodgers

In the late 1940s, Branch Rickey was club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Dodgers began to scout Robinson, and Rickey eventually selected him from a list of promising African-American players. Robinson became the first player in fifty-seven years to break the Baseball color line.

In 1946, the Dodgers assigned Jackie Robinson to the Montreal Royals. Jackie proceeded to lead the International League in batting average with a .349 average, and fielding percentage with a .985 percentage. That winter he also married Rachel Isum, his former UCLA classmate. It should be noted that Robinson was greeted with strong support by the Montreal fans and not hatred as he would later feel in the Major League. Because of Jackie's play in 1946, the Dodgers called him up to play for the major league club in 1947. Robinson made his Major League debut on April 15, 1947, playing first base when he went 0 for 3 against the Boston Braves.

Throughout the season, Robinson experienced harassment at the hands of both players and fans. He was verbally abused by both his own teammates and by members of opposing teams. Some Dodger players insinuated they would sit out rather than play alongside Robinson. The mutiny ended when Dodger management informed those players that they were welcome to find employment elsewhere.

On April 22, 1947, during a game between the Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies, Phillies players called Jackie a "nigger" from their dugout, and yelled that he should "go back to the cotton fields." Rickey would later recall that the Phillies' manager, Ben Chapman, "did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers. When he poured out that string of unconscionable abuse, he solidified and united thirty men." Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler admonished the Phillies and asked Chapman to pose for photographs with Robinson as a conciliatory gesture.

Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who would be a teammate of Robinson's for the better part of a decade, was one of the few players who publicly stood up for Robinson during his rookie season. During the team's first road trip, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Robinson was being heckled by fans when Reese, the Dodgers team captain, walked over and put his arm around Robinson in a gesture of support that quieted the fans and has now gained near-legendary status. Reese was once quoted saying about Robinson "You can hate a man for many reasons, color is not one of them." In addition, the Jewish baseball star Hank Greenberg, who had faced considerable anti-Semitism earlier in his career, made a point of welcoming Robinson to the major leagues.

For his services, Jackie earned the major-league minimum salary of $5,000, which was standard for many rookies at the time. That year, he played in 151 games, hit .297, led the National League in stolen bases and won the first-ever Rookie of the Year Award. Although Jackie played every game that season at first base, Robinson spent most of his career as a second baseman.

Two years later, Jackie won the Most Valuable Player award for the National League. He would win his only championship ring when the Dodgers beat the New York Yankees in the 1955 World Series. After the 1956 season, Robinson was traded by the Dodgers to the New York Giants for Dick Littlefield and $30,000 cash. Rather than report to the arch-rival Giants, Robinson chose to retire at age 37.

Robinson was a disciplined hitter and a versatile fielder. He had a .311 career batting average and substantially more walks than strikeouts and was an outstanding base stealer. No other player since World War I has stolen home more than Robinson, who did it 19 times in his career. During his career, the Dodgers played in six World Series and Jackie played in six All-Star games. He is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame and a member of the All-Century Team. In one of his most famous quotes, he said "I'm not concerned with your liking or disliking me... all I ask is that you respect me as a human being."

Post-baseball life

August 28, 1963

From the National Archives

Robinson retired on January 5, 1957. He had wanted to manage or coach in the major leagues, but received no offers. He became a vice-president for the Chock Full O' Nuts corporation instead, and served on the board of the NAACP until 1967, when he resigned. During the early to late 1950s, Jackie and Louis Ostrer owned Jackie Robinson's, a men's clothing store located on 125th St. in New York City.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility, becoming the first African-American so honored. In 1965, Robinson served as a color commentator for ABC's Game of the Week telecasts. On June 4, 1972, the Dodgers retired his uniform number 42 alongside Roy Campanella (39) and Sandy Koufax (32).

Robinson made his final public appearance on October 14, 1972, before Game 2 of the World Series. He used this chance to express his wish for a black manager to be hired by a Major League Baseball team.

This wish was granted two years later, following the 1974 season, when the Cleveland Indians gave their managerial post to Frank Robinson, a Hall of Fame bound slugger who was then still an active player, and no relation to Jackie Robinson. At the press conference announcing his hiring, Frank expressed his wish that Jackie had lived to see the moment.

In 1971, his eldest son, Jackie, Jr., who had beaten back drug problems and was working as a Daytop Village counselor, was killed in an automobile accident. Also, Jackie suffered from diabetes, virtually went blind, and suffered heart problems.

Robinson died from heart problems and diabetes complications in Stamford, Connecticut on October 24, 1972 and was interred in the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. The highway that goes through the cemetery (previously known as the Interborough Parkway) was renamed the Jackie Robinson Parkway in 1997.

Awards and recognition

worst player of the year

See also

- List of first black Major League Baseball players by team and date

- DHL Hometown Heroes

- List of African American firsts

Notes

- Rothe, p544

- ^ Williams, Michael W.- Editor. An African American Encyclopedia. 1993.

- MLB.com

- Bigelow, p225

- ^ Rampersad pp10-11 Cite error: The named reference "Rampersad" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Robinson, p9

- Rampersad, p23

- Rampersad, p35

- Rampersad, p36

- Rampersad, pp 36-37

- Rampersad, p37

- Rampersad, pp37-39

- Rampersad, pp40-41

- Rampersad, p47

- Rampersad, pp50-53

- Rampersad, p54

- Rampersad, pp59-61

- http://www.jackierobinson.com/about/bio.html

- ^ http://www.galegroup.com/free_resources/bhm/bio/robinson_j.htm

- http://www.loc.gov/rr/mss/text/robinsnj.html

- http://www.afro.com/Robinson/army.html

- http://losangeles.dodgers.mlb.com/la/history/jackie_robinson_timeline/timeline_index.jsp

- Thorn,p.5"

- TheJournalofSportsHistory.org

- Ken Burns' documentary, BASEBALL, Part 6, minute 120

- Ken Burns' documentary, BASEBALL, Part 6, minute 122

- http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/R/Robinson_Jackie.stm

- http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/robinson/index.htm

- http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/jackie/news/story?id=2828584

- http://www.nycroads.com/roads/jackie-robinson/

References

- Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson, a Biography, Alfred A. Knopf (New York), 1997. ISBN 0-679-44495-5

- Tygiel, Jules. Baseball's Great Experiment, Oxford (USA), New York, ISBN 0195106199

- Bigelow, Barbara Carlisle, ed. Contemporary Black Biography vol. 6. Gale Research Inc. 1994. ISBN 0-8103-8558-9

- Moritz, Charles, ed. Current Biography Yearbook 1972, H.W. Wilson Co, New York, 1972. ISBN 0-8242-0493-X

- Rothe, Anna, ed. Current Biography, Who's News and Why 1947, H.W. Wilson Co, New York, 1948.

- MLB.com - http://newyork.yankees.mlb.com/NASApp/mlb/nyy/history/retired_numbers.jsp

- Journal of Sports History - http://thejournalofsportshistory.org/history-of-baseball/jackie-robinson-a-triple-threat.html

- Robinson, Jackie. I Never Had It Made. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1972

- Robinson, Sharon. Promises To Keep: How Jackie Robinson Changed America Scholastic, 2004.

- Thorn, John. "Our Game" pp1-10 In Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball 7th ed. John Thorn et al eds. Total Sports Publishing, New York, 1992

- Williams, Michael W.- Ed. An African American Encyclopedia 1993.

- Frommer, Harvey. Jackie Robinson Watts Press, 1984.

External links

- Official Website of Jackie Robinson

- Jackie Robinson Foundation Website

- archives.gov Correspondences with the White House

- baseballhalloffame.org Baseball Hall of Fame page

- baseball-reference.com Baseball statistics

- Jackie Robinson (entry in the New Georgia Encyclopedia)

- loc.gov Library of Congress Robinson collection

- Template:Nndb name

- Template:Find A Grave

| Preceded byNone, first holder of the award | Major League Rookie of the Year 1947 |

Succeeded byAlvin Dark |

| Preceded byStan Musial | National League Most Valuable Player 1949 |

Succeeded byJim Konstanty |

| Preceded byStan Musial | National League Batting Champion 1949 |

Succeeded byStan Musial |

| Major League Baseball All-Century Team | |

|---|---|

| Pitchers | |

| Catchers | |

| Infielders | |

| Outfielders | |

- 1919 births

- 1972 deaths

- African American baseball players

- African American basketball players

- African Americans' rights activists

- American Methodists

- American military personnel of World War II

- Baseball Hall of Fame

- Baseball players who have hit for the cycle

- Baseball Rookies of the Year

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Jackie Robinson

- Major League Baseball announcers

- Major league second basemen

- Major league players from Georgia

- Negro League baseball players

- National League All-Stars

- National League batting champions

- People from Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Pasadena, California

- People from Brooklyn

- People from New York City

- People from Stamford, Connecticut

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- UCLA Bruins football players

- UCLA Bruins men's basketball players

- United States Army officers

- University of California, Los Angeles alumni