| Revision as of 23:57, 27 August 2007 editRamdrake (talk | contribs)8,680 edits Revert - obsolete, outdated view not relevant.← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:25, 28 August 2007 edit undoTaharqa (talk | contribs)6,029 edits →Islamisation: False implication.. These were Swahili colonies, influenced by Islam, not Arab colonies. Ibn Battuta didn't describe Arabs at allNext edit → | ||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

| Islam also spread through the interior of ], as the religion of the ]s of the ] (c. 1235–1400) and many rulers of the ] (c. 1460–1591). Following the fabled 1324 ] of ], ] became renowned as a center of Islamic scholarship as sub-Saharan Africa's first university. That city had been reached in 1352 by the great Arab traveller ], whose journey to Mombasa and Quiloa (]) provided the first accurate knowledge of those flourishing Muslim cities on the east African seaboards. | Islam also spread through the interior of ], as the religion of the ]s of the ] (c. 1235–1400) and many rulers of the ] (c. 1460–1591). Following the fabled 1324 ] of ], ] became renowned as a center of Islamic scholarship as sub-Saharan Africa's first university. That city had been reached in 1352 by the great Arab traveller ], whose journey to Mombasa and Quiloa (]) provided the first accurate knowledge of those flourishing Muslim cities on the east African seaboards. | ||

| Arab progress southward was stopped by the broad belt of dense forest, stretching almost across the continent somewhat south of 10° North latitude, which barred their advance much as the Sahara had proved an obstacle to their predecessors. The rainforest cut them off from knowledge of the ] and of all Africa beyond. One of the regions which was the last to come under Arab rule was that of Nubia, which had been controlled by Christians up to the 14th century. | |||

| For a time the ] Muslim conquests in South Europe had virtually made of the Mediterranean a ] lake, but the expulsion in the 11th century of the ] from ] and southern ] by the ] was followed by descents of the conquerors on Tunisia and Tripoli. Somewhat later a busy trade with the African coastlands, and especially with Egypt, was developed by ], ], ] and other cities of North Italy. By the end of the 15th century Spain had completely removed the Muslims, but even while the Moors were still in ], ] was strong enough to carry the war into Africa. In 1415 a Portuguese force captured the citadel of ] on the Moorish coast. From that time onward Portugal repeatedly interfered in the affairs of Morocco, while Spain acquired many ports in Algeria and Tunisia. | For a time the ] Muslim conquests in South Europe had virtually made of the Mediterranean a ] lake, but the expulsion in the 11th century of the ] from ] and southern ] by the ] was followed by descents of the conquerors on Tunisia and Tripoli. Somewhat later a busy trade with the African coastlands, and especially with Egypt, was developed by ], ], ] and other cities of North Italy. By the end of the 15th century Spain had completely removed the Muslims, but even while the Moors were still in ], ] was strong enough to carry the war into Africa. In 1415 a Portuguese force captured the citadel of ] on the Moorish coast. From that time onward Portugal repeatedly interfered in the affairs of Morocco, while Spain acquired many ports in Algeria and Tunisia. | ||

Revision as of 07:25, 28 August 2007

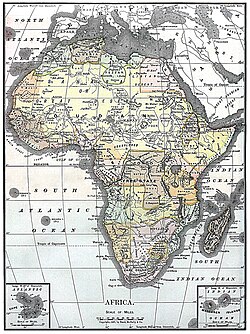

The History of Africa began in the Bronze Age with the earliest written records from ancient Egypt.

Evolution of hominids and Homo sapiens in Africa

Main article: Human evolutionAccording to the latest paleontological and archaeological evidence, hominids were already in existence at least five million years ago. These animals were still very much like their close cousins, the great African apes, but had adopted a bipedal form of locomotion, giving them crucial advantage in the struggle for survival, as this enabled them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna, at a time when Africa was drying up, with savanna encroaching on forested areas.

By 3 million years ago several australopithecine hominid species had developed throughout southern, eastern and central Africa.

The next major evolutionary step occurred approximately 2 million years ago, with the advent of Homo habilis, the first species of hominid capable of making tools. This enabled H. habilis to begin eating meat, using his stone tools to scavenge kills made by other predators, and harvest cadavers for their bones and marrow. In hunting, H. habilis was probably not capable of competing with large predators, and was still more prey than hunter, although he probably did steal eggs from nests, and may have been able to catch small game, and weakened larger prey (cubs and older animals).

Around one million years ago Homo erectus had evolved. With his relatively large brain (1,000 cc), he mastered the African plains, fabricating a variety of stone tools that enabled him to become a hunter equal to the top predators. In addition Homo erectus mastered the art of making fire, and was the first hominid to leave Africa, colonizing the entire Old World, and later giving rise to Homo floresiensis. This is now contested by new theories suggesting that Homo georgicus, a Homo habilis descendent, was the first and most primitive hominid to ever live outside Africa.

The fossil record shows Homo sapiens living in southern and eastern Africa at least 100,000 and possibly 150,000 years ago. Around 40,000 years ago, their expansion out of Africa launched the colonization of our planet by modern human-beings. Their migration is indicated by linguistic, cultural and (increasingly) computer-analyzed genetic evidence (see also Cavalli-Sforza).

The rise of civilization and agriculture

At the end of the Ice Age (guessed to have been around 10,500 BC), the Sahara had become a green fertile valley again, and its African populations returned from the interior and coastal highlands in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the warming and drying climate meant that by 5000 BC the Sahara region was becoming increasingly drier. The population trekked out of the Sahara region towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract where they made permanent or semi-permanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in Central and Eastern Africa. Since then dry conditions have prevailed in Eastern Africa.

The domestication of cattle in Africa precedes agriculture and seems to have existed alongside hunter-gathering cultures. It is speculated that by 6000 BC cattle were already domesticated in North Africa. In the Sahara-Nile complex, people domesticated many animals including the pack ass, and a small screw horned goat which was common from Algeria to Nubia.

Agriculturally, the first cases of domestication of plants for agricultural purposes occurred in the Sahel region circa 5000 BC, when sorghum and African rice began to be cultivated. Around this time, and in the same region, the small guinea fowl became domesticated.

According to the Oxford Atlas of World History, in the year 4000 BC the climate of the Sahara started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace. This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink rather significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and helped to cause migrations of farming communities to the more tropical climate of West Africa.

By 3000 BC agriculture arose independently in both the tropical portions of West Africa, where African yams and oil palms were domesticated, and in Ethiopia, where coffee and teff became domesticated. No animals were independently domesticated in these regions, although domestication did spread there from the Sahel and Nile regions. Agricultural crops were also adopted from other regions around this time as pearl millet, cowpea, groundnut, cotton, watermelon and bottle gourds began to be grown agriculturally in both West Africa and the Sahel Region while finger millet, peas, lentil and flax took hold in Ethiopia.

The international phenomenon known as the Beaker culture began to affect western North Africa. Named for the distinctively shaped ceramics found in graves, the Beaker culture is associated with the emergence of a warrior mentality. North African rock art of this period depict christina o'dell animals but also places a new emphasis on the human figure, equipped with weapons and adornments. People from the φGreat Lakes Region of Africa settled along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea to become the proto-Canaanites who dominated the lowlands between the Jordan River, the Mediterranean and the Sinai Desert.

By the 1st millennium BC, ironworking had been introduced in Northern Africa and quickly began spreading across the Sahara into the northern parts of sub-saharan Africa and by 500 BC, metalworking began to become commonplace in West Africa, possibly after being introduced by the Carthaginians. Ironworking was fully established by roughly 500 BC in areas of East and West Africa, though other regions didn't begin ironworking until the early centuries AD. Some copper objects from Egypt, North Africa, Nubia and Ethiopia have been excavated in West Africa dating from around 500 BC time period, suggesting that trade networks had been established by this time.

Neolithic prehistoric cultures

Neolithic rock engravings, or 'petroglyphs' and the megaliths in the Sahara desert of Libya attest to early hunter-gatherer culture in the dry grasslands of North Africa during the glacial age. The region of the present Sahara was an early site for the practice of agriculture (in the second stage of the culture characterized by the so-called "wavy-line ceramics" ca. 4000 BCE.). However, after the desertification of the Sahara, settlement in North Africa became concentrated in the valley of the Nile, where the pre-literate Nomes of Egypt laid a base for the culture of ancient Egypt. Archeological findings show that primitive tribes lived along the Nile long before the dynastic history of the pharaohs began. By 6000 B.C., organized agriculture had appeared.

From around 500 B.C. to around 500 A.D., the civilization of the Garamantes (probably the ancestors of the Tuareg) existed in what is now the Libyan desert.

Linguistic evidence suggests the Bantu people (e.g. Xhosa and Zulu) have emigrated southwestward from what is now Cameroon and southeastern Nigeria into former Khoisan ranges and displaced them during the last 4000 years or so. Bantu populations used a distinct suite of crops suited to tropical Africa, including cassava and yams. This farming culture is able to support more persons per unit area than hunter-gatherers. The traditional Congo range goes from the northern deserts right down to the temperate regions of the south, in which the Congo crop suite fails from frost. Their primary weapons historically were bows and stabbing spears with shields.

Ethiopia had a distinct, ancient culture with an intermittent history of contact with Eurasia after the diaspora of hominids out of Africa. It preserved a unique language, culture and crop system. The crop system is adapted to the northern highlands and does not partake of any other area's crops. The most famous member of this crop system is coffee, but one of the more useful plants is sorghum, a dry-land grain; teff is also endemic to the region.

Ancient cultures also existed all along the Nile, and in modern-day Ghana.

History of Africa until 1880 A.D.

Bantu expansion

Main article: Bantu expansionIt is believed by some historians that the Bantu first originated around the Benue-Cross rivers area in southeastern Nigeria and spread over Africa to the Zambia area. It should be noted here that the term "Bantu" suffers from its connection with South Africa's "apartheid" regime. Sometime in the second millennium BC, perhaps triggered by the drying of the Sahara and pressure from the migration of Saharans into the region, they were forced to expand into the rainforests of central Africa (phase I). About 1000 years afterward, they began a more rapid second phase of expansion beyond the forests into southern and eastern Africa. Then sometime in the first millennium new agricultural techniques and plants were developed in Zambia, likely imported from South East Asia via Malay speaking Madagascar. With these techniques another Bantu expansion occurred centered on this new location (phase III).

West Africa

Main article: History of West AfricaThere were many great empires in Sub-Saharan Africa over the past few millennia, especially in West Africa where important trade routes and good agricultural land allowed large states to develop. These included the Nok, Mali Empire, Oba of Benin, the Kanem-Bornu Empire, the Fulani Empire, the Dahomey, Oyo, Aro confederacy, The Efik/Ibibio/Annang Kingdom of the Coastal Southeastern Nigeria Efik, Ibibio, Annang, the Ashanti Empire, and the Songhai Empire.

Also common in the region were loose federations of city-states such as those of the Yoruba and Hausa.

Trans-Saharan trade

Main article: Trans-Saharan tradeTrade between Mediterranean countries and West Africa across the Sahara Desert, was an important trade pattern from the eighth century until the late sixteenth century. This trade was conducted by caravans of Arabian camels. These camels would be fattened for a number of months on the plains of either the Maghreb or the Sahel before being assembled into caravans.

Central Africa

Main article: Early Congolese historyFirst settled by Pygmies, Central Africa was later settled by Bantu groups, forming the basis for ethnic affinities and rivalries in the present day. Several Bantu kingdoms — notably those of the Kongo, the Loango, and the Teke — built trade links leading into the Congo River basin. The first European contacts came in the late 16th century, and commercial relationships were quickly established with the kingdoms —trading for slaves captured in the interior. The coastal area was a major source for the transatlantic slave trade, and when that commerce ended in the early 19th century, the power of the Bantu kingdoms eroded.

The Mandara kingdom in present day Cameroon was founded around 1500 and erected magnificent fortified structures, the purpose and exact history of which is still unresolved. The Aro Confederacy of Nigeria, had presence in Western Cameroon due to migration in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the late 1770s and early 1800s, the Fulani, a pastoral Islamic people of the western Sahel, conquered most of what is now northern Cameroon, subjugating or displacing its largely non-Muslim inhabitants.

The Central African Republic is believed to have been settled from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the Kanem-Bornu, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based around Lake Chad region and along Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present-day C.A.R, using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from which slaves were traded north across the Sahara. Population migration in the 18th and 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, Banda, and Baya-Mandjia.

Southern Africa

Main articles: History of South Africa and History of ZimbabweLarge political units were uncommon but there were exceptions, most notably Great Zimbabwe and the Zulu Empire. It is supposed by some historians that (perhaps around 1,000 AD) the Bantu expansion had reached modern day Zimbabwe and South Africa. In Zimbabwe historians find what is believed to be the first major southern hemisphere empire. With its capital at Great Zimbabwe, it controlled trading routes from South Africa to north of the Zambezi, trading gold, copper, precious stones, animal hides, ivory and metal goods with the Swahili coast.

It has been seen that Portugal took no steps to acquire the southern part of the continent. To the Portuguese the Cape of Good Hope was simply a landmark on the road to India, and mariners of other nations who followed in their wake used Table Bay only as a convenient spot wherein to refit on their voyage to the East. By the beginning of the 17th century the bay was much resorted to for this purpose, chiefly by British and Dutch vessels.

In 1620, wanting to forestall the Dutch, two officers of the British East India Company, on their own initiative, took possession of Table Bay in the name of King James, fearing otherwise that British ships would be "frustrated of watering but by license." Their action was not approved in London and the proclamation they issued remained without effect. The Netherlands profited by the apathy of the British. On the advice of sailors who had been shipwrecked in Table Bay the Netherlands East India Company, in 1651, sent out a fleet of three small vessels under Jan van Riebeeck which reached Table Bay on the April 6, 1652 when, 164 years after its discovery, the first permanent white settlement was made in South Africa. The Portuguese, whose power in Africa was already waning, were not in a position to interfere with the Dutch plans, and Britain was content to seize the island of Saint Helena as a halfway house to the East. Until the Dutch landed, the southern tip of Africa was inhabited by a sparse Khoisan speaking culture including both Bushmen (hunter-gatherers) and Khoi (herders). Europeans found it a paradise for their temperate crop suites.

In its inception the settlement at the Cape was not intended to become an African colony, but was regarded as the most westerly outpost of the Dutch East Indies. Nevertheless, despite the paucity of ports and the absence of navigable rivers, the Dutch colonists, including Huguenots who had fled France, gradually spread northward.

Ethiopia

Main articles: History of Ethiopia and NubiaEthiopia had centralized rule for many millennia and the Aksumite Kingdom, which developed there, had created a powerful regional trading empire (with trade routes going as far as India).

At the period of her greatest power, Portugal also had close relations/alliances with Ethiopia. In the ruler of Ethiopia (to whose dominions a Portuguese traveller had penetrated before Vasco da Gama's memorable voyage) the Portuguese imagined they had found the legendary Christian king, Prester John for whom they had long been searching. A few decades later, the very existence of a Christian Ethiopia was threatened by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi of Adal, backed by Ottoman cannons and muskets, while the Ethiopians possessed but a few muskets and cannons. With the aid of 400 Portuguese musketmen under Cristóvão da Gama during 1541–1543, the Ethiopians were able to defeat the Imam and preserve the Solomonic dynasty. After da Gama's time, Portuguese Jesuits travelled to Ethiopia in hopes of converting the populace from Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity. While they failed in their efforts to convert the Ethiopians to Roman Catholicism (though Emperor Susenyos did so briefly), they acquired an extensive knowledge of the country. Pedro Paez in 1605 and, 20 years later, Jerónimo Lobo, both visited the sources of the Blue Nile. In the 1660s the Portuguese were expelled from the Ethiopian dominions and Emperor Fasilides ordered all of the books of the "Franks" burnt in 1665. At this time Portuguese influence on the Zanzibar coast faded before the power of the Arabs of Muscat, and by 1730 no point on the east coast north of Cabo Delgado was held by Portugal.

East Africa

Main article: Swahili peopleHistorically, the Swahili could be found as far north as Mogadishu in Somalia, and as far south as Rovuma River in Mozambique. Although once believed to be the descendants of Persian colonists, the ancient Swahili are now recognized by most historians, historical linguists, and archaeologists as a Bantu people who had sustained and important interactions with Muslim merchants beginning in the late 7th and early 8th century AD. By the 1100s the Swahili emerged as a distinct and powerful culture, focused around a series of coastal trading towns, the most important of which was Kilwa. Ruins of this golden age still survive.

One region that saw considerable state formation due to its high population and agricultural surplus was the Great Lakes region where states such as Rwanda, Burundi, and Buganda became strongly centralized.

Neglecting the comparatively poor and thinly inhabited regions of South Africa, the Portuguese no sooner discovered than they coveted the flourishing cities held by Muslim, Swahili-speaking people between Sofala and Cape Guardafui. By 1520 the southern Muslim sultanates had been seized by Portugal, Moçambique being chosen as the chief city of Portugal's East African possessions. Nor was colonial activity confined to the coastlands. The lower and middle Zambezi valley was explored by the Portuguese during the 16th and 17th centuries), and here they found tribes who had been for many years in contact with the coastal regions. Strenuous efforts were made to obtain possession of the country (modern Zimbabwe) known to them as the kingdom or empire of Monomotapa, where gold had been worked from about the 12th century, and whence the Arabs, whom the Portuguese dispossessed, were still obtaining supplies in the 16th century. Several expeditions were despatched inland from 1569 onward and considerable quantities of gold were obtained. Portugal's hold on the interior, never very effective, weakened during the 17th century, and in the middle of the 18th century ceased with the abandonment of their forts in the Manica district.

European exploration

Main article: European exploration of AfricaDuring the fifteenth century Prince Henry "the Navigator," son of King John I, planned to acquire African territory for Portugal. Under his inspiration and direction Portuguese navigators began a series of voyages of exploration which resulted in the circumnavigation of Africa and the establishment of Portuguese sovereignty over large areas of the coastlands.

Portuguese ships rounded Cape Bojador in 1434, Cape Verde in 1445, and by 1480 the whole Guinea coast was known to the Portuguese. In 1482 Diogo Cão reached the mouth of the Congo, the Cape of Good Hope was rounded by Bartolomeu Dias in 1488, and in 1498 Vasco da Gama, after having rounded the Cape, sailed up the east coast, touched at Sofala and Malindi, and went from there to India. Portugal claimed sovereign rights wherever its navigators landed, but these were not exercised in the extreme south of the continent.

The Guinea coast, as the nearest to Europe, was first exploited. Numerous European forts and trading stations were established, the earliest being São Jorge da Mina (Elmina), begun in 1482. The chief commodities dealt in were slaves, gold, ivory and spices. The European discovery of America (1492) was followed by a great development of the slave trade, which, before the Portuguese era, had been an overland trade almost exclusively confined to Muslim Africa. The lucrative nature of this trade and the large quantities of alluvial gold obtained by the Portuguese drew other nations to the Guinea coast. English mariners went there as early as 1553, and they were followed by Spaniards, Dutch, French, Danish and other adventurers. Colonial supremacy along the coast passed in the 17th century from Portugal to the Netherlands and from the Dutch in the 18th and 19th centuries to France and Britain. The whole coast from Senegal to Lagos was dotted with forts and "factories" of rival European powers, and this international patchwork persisted into the 20th century although all the West African hinterland had become either French or British territory.

Southward from the mouth of the Congo to the region of Damaraland (in what is present-day Namibia), the Portuguese, from 1491 onward, acquired influence over the inhabitants, and in the early part of the 16th century through their efforts Christianity was largely adopted in the Kongo Empire. An incursion of tribes from the interior later in the same century broke the power of this semi-Christian state, and Portuguese activity was transferred to a great extent farther south, São Paulo de Loanda (present-day Luanda) being founded in 1576. Before Angolan independence in 1975, the sovereignty of Portugal over this coastal region, except for the mouth of the Congo, had been only once challenged by a European power, the Dutch, from 1640 to 1648 in which Portugal lost control of the seaports.

African slave trade

Main article: African slave tradeThe earliest external African slave trade was trans-Saharan. Although there had long been some trading along the Nile River and very limited trading across the western desert, the transportation of large numbers of slaves did not become viable until camels were introduced from Arabia in the 10th century. At this point, a trans-Saharan trading network came into being to transport slaves north. Unlike the Americas, slaves in North Africa were mainly servants rather than labourers, and an equal or greater number of females than males were taken, who were often employed as chambermaids to the women of northern harems. It was also not uncommon to turn male slaves into eunuchs.

The Atlantic slave trade was a later development, but would eventually become far greater and have a much bigger impact. Increasing penetration of the Americas by the Portuguese created a huge demand for labour in Brazil. Workers were needed for agriculture, mining and other tasks. To meet this new demand, a trans-Atlantic slave trade developed. Slaves purchased in those West African regions known to Europeans as the Slave Coast, Gold Coast, and Côte d'Ivoire were often the unfortunate byproduct of fighting between rival African states. Powerful African kings on the Bight of Biafra might sell their captives internally or exchange them with European slave traders for trade goods such as firearms,rum, fabrics and seed grain. It should be noted that European traders also conducted their own, quite independent, slave raids.

North Africa

Ancient Egypt

Main articles: History of ancient Egypt and KushAfrica's earliest evidence of written history was in Ancient Egypt, and the Egyptian calendar is still used as the standard for dating Bronze Age and Iron Age cultures throughout the region.

In about 3100 B.C. Egypt was united under the first known Narmer, who inaugurated the first of the 30 dynasties into which Egypt's ancient history is divided: the Old, Middle Kingdoms and the New Kingdom. The pyramids at Giza (near Cairo), which were built in the Fourth dynasty, testify to the power of the pharaonic religion and state. The Great Pyramid, the tomb of Pharaoh Khufu (also known as Cheops), is the only surviving monument of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Ancient Egypt reached the peak of its power, wealth, and territorial extent in the period called the New Empire (1567–1085 B.C.).

The importance of Ancient Egypt to the development of the rest of Africa has been debated. The earlier generation of Western academia generally saw Egypt as a Mediterranean civilization with little impact on the rest of Africa. Recent scholarship however, has began to discredit this notion. Some have argued that various early Egyptians like the Badarians probably migrated northward from Nubia, while others see a wide-ranging movement of peoples across the breadth of the Sahara before the onset of desiccation. Whatever may be the origins of any particular people or civilization, however, it seems reasonably certain that the predynastic communities of the Nile valley were essentially indigenous in culture, drawing little inspiration from sources outside the continent during the several centuries directly preceding the onset of historical times... (Robert July, Pre-Colonial Africa, 1975, p. 60-61)

Phoenician, Greek and Roman colonization

Separated by the 'sea of sand', the Sahara, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa have been linked by fluctuating trans-Saharan trade routes. Phoenician, Greek and Roman history of North Africa can be followed in entries for the Roman Empire and for its individual provinces in the Maghreb, such as Mauretania, Africa, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, Aegyptus etc.

In East Africa Ethiopia has been the only state which throughout historic times has (except for a brief period during World War II) maintained its independence. Countries bordering the Mediterranean were colonised and settled by the Phoenicians before 1000 BC. Carthage, founded about 814 BC, speedily grew into a city without rival in the Mediterranean. The Phoenicians subdued the Berber tribes who, then as now, formed the bulk of the population, and became masters of all the habitable region of North Africa west of the Great Syrtis, and found in commerce a source of immense prosperity.

Greeks founded the city of Cyrene in Ancient Libya around 631 BC. Cyrenaica became a flourishing colony, though being hemmed in on all sides by absolute desert it had little or no influence on inner Africa. The Greeks, however, exerted a powerful influence in Egypt. To Alexander the Great the city of Alexandria owes its foundation (332 BC), and under the Hellenistic dynasty of the Ptolemies attempts were made to penetrate southward, and in this way was obtained some knowledge of Ethiopia.

The three powers of Cyrenaica, Egypt and Carthage were eventually supplanted by the Romans. After centuries of rivalry with Rome, Carthage finally fell in 146 BC. Within little more than a century Egypt and Cyrene had become incorporated in the Roman empire. Under Rome the settled portions of the country were very prosperous, and a Latin strain was introduced into the land. Though Fezzan was occupied by them, the Romans elsewhere found the Sahara an impassable barrier. Nubia and Ethiopia were reached, but an expedition sent by the emperor Nero to discover the source of the Nile ended in failure. The utmost extent of Mediterranean geographical knowledge of the continent is shown in the writings of Ptolemy (2nd century), who knew of or guessed the existence of the great lake reservoirs of the Nile, of trading posts along the shores of the Indian Ocean as far south as Rhapta in modern Tanzania, and had heard of the river Niger.

Interaction between Asia, Europe and North Africa during this period was significant, major effects include the spread of classical culture around the shores of the Mediterranean; the continual struggle between Rome and the Berber tribes; the introduction of Christianity throughout the region, and the cultural effects of the churches in Tunisia, Egypt and Ethiopia. The classical era drew to a close with the invasion and conquest of Rome's African provinces by the Vandals in the 5th century. Power passed back in the following century to the Byzantine Empire.

Islamisation

Muslim Arabs conquered northern Africa from the Red Sea to the Atlantic and continued into Spain beginning with the invasion of Egypt in the 7th century. Throughout North Africa Christianity nearly disappeared, except in Egypt where the Coptic Church remained strong partly because of the influence of Ethiopia, which was not approached by the Muslims because of Ethiopia's history of harboring early Muslim converts from retaliation by pagan Arab tribes. Some argue that when the Arabs had converted Egypt they attempted to wipe out the Copts, Ethiopia, who also practiced Coptic Christianity, warned the Muslims that if they attempted to wipe out the Copts, Ethiopia would decrease the flow of Nile water from getting to Egypt. This was because Lake Tana, which was in Ethiopia was the source of the Blue Nile which is flows into the greater Nile. Some believe this to be one of the reasons that the Coptic minorities still exist today, but it is unlikely because of Ethiopia's weak military standing against the Afro-Arabs.

In the 11th century there was a sizable Arab immigration, resulting in a large absorption of Berber culture. Even before this the Berbers had very generally adopted the speech and religion of their conquerors. Arab influence and the Islamic religion thus became indelibly stamped on northern Africa. Together they spread southward across the Sahara. They also became firmly established along the eastern seaboard, where Arabs, Persians and Indians planted flourishing colonies, such as Mombasa, Malindi and Sofala, playing a role, maritime and commercial, analogous to that filled in earlier centuries by the Carthaginians on the northern seaboard. Until the 14th century, Europe and the Arabs of North Africa were both ignorant of these eastern cities and states.

The first Arab immigrants had recognized the authority of the caliphs of Baghdad, and the Aghlabite dynasty—founded by Aghlab, one of Haroun al-Raschid's generals, at the close of the 8th century—ruled as vassals of the caliphate. However, early in the 10th century the Fatimid dynasty established itself in Egypt, where Cairo had been founded AD 968, and from there ruled as far west as the Atlantic. Later still arose other dynasties such as the Almoravides and Almohades. Eventually the Turks, who had conquered Constantinople in 1453, and had seized Egypt in 1517, established the regencies of Algeria, Tunisia and Tripoli (between 1519 and 1551), Morocco remaining an independent Arabized Berber state under the Sharifan dynasty, which had its beginnings at the end of the 13th century.

Under the earlier dynasties Arabian or Moorish culture had attained a high degree of excellence, while the spirit of adventure and the proselytizing zeal of the followers of Islam led to a considerable extension of the knowledge of the continent. This was rendered more easy by their use of the camel (first introduced into Africa by the Persian conquerors of Egypt), which enabled the Arabs to traverse the desert. In this way Senegambia and the middle Niger regions fell under the influence of the Arabs and Berbers.

Islam also spread through the interior of West Africa, as the religion of the mansas of the Mali Empire (c. 1235–1400) and many rulers of the Songhai Empire (c. 1460–1591). Following the fabled 1324 hajj of Kankan Musa I, Timbuktu became renowned as a center of Islamic scholarship as sub-Saharan Africa's first university. That city had been reached in 1352 by the great Arab traveller Ibn Battuta, whose journey to Mombasa and Quiloa (Kilwa) provided the first accurate knowledge of those flourishing Muslim cities on the east African seaboards.

Arab progress southward was stopped by the broad belt of dense forest, stretching almost across the continent somewhat south of 10° North latitude, which barred their advance much as the Sahara had proved an obstacle to their predecessors. The rainforest cut them off from knowledge of the Guinea coast and of all Africa beyond. One of the regions which was the last to come under Arab rule was that of Nubia, which had been controlled by Christians up to the 14th century.

For a time the African Muslim conquests in South Europe had virtually made of the Mediterranean a Muslim lake, but the expulsion in the 11th century of the Saracens from Sicily and southern Italy by the Normans was followed by descents of the conquerors on Tunisia and Tripoli. Somewhat later a busy trade with the African coastlands, and especially with Egypt, was developed by Venice, Pisa, Genoa and other cities of North Italy. By the end of the 15th century Spain had completely removed the Muslims, but even while the Moors were still in Granada, Portugal was strong enough to carry the war into Africa. In 1415 a Portuguese force captured the citadel of Ceuta on the Moorish coast. From that time onward Portugal repeatedly interfered in the affairs of Morocco, while Spain acquired many ports in Algeria and Tunisia.

Portugal, however, suffered a crushing defeat in 1578 at al Kasr al Kebir, the Moors being led by Abd el Malek I of the then recently established Saadi Dynasty. By that time the Spaniards had lost almost all their African possessions. The Barbary states, primarily from the example of the Moors expelled from Spain, degenerated into mere communities of pirates, and under Turkish influence civilization and commerce declined. The story of these states from the beginning of the 16th century to the third decade of the 19th century is largely made up of piratical exploits on the one hand and of ineffectual reprisals on the other.

European exploration and conquest

19th-century European explorers

Main articles: Colonization of Africa and Scramble for AfricaAlthough the Napoleonic Wars distracted the attention of Europe from the exploration of Africa, there were nevertheless significant developments. The invasion of Egypt (1798–1803) first by France and then by Great Britain resulted in an effort by Turkey to regain direct control over that country, followed in 1811 by the establishment under Mehemet Ali of an almost independent state, and the extension of Egyptian rule over the eastern Sudan (from 1820 onward). In South Africa the struggle with Napoleon led the United Kingdom to seize Dutch settlements at the Cape, and in 1814 Cape Colony, which had been continuously occupied by British troops since 1806, was formally ceded to the British crown.

Considerable changes had meanwhile been made in other parts of the continent, the most notable being the invasion of Algiers by France in 1830. This action put an end to the independent Barbary states, a major obstacle to Frances Mediterranean strategy. Egyptian authority continued its southward expansion with consequent additions to European the knowledge of the Nile. The city of Zanzibar, on the island of that name rapidly attained importance. Accounts of a vast inland sea, and the "discovery" in 1840–1848, by the missionaries Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johann Rebmann, of the snow-clad mountains of Kilimanjaro and Kenya, stimulated in Europe the desire for further knowledge.

By the middle of the 19th century, Protestant missions were carrying on active missionary work on the Guinea coast, in South Africa and in the Zanzibar dominions. It was being conducted among people of whom Europeans knew little.In many instances missionaries turned explorer or became agents of trade and colonialism. One of the first to attempt to fill up the remaining blank spaces in the European map was David Livingstone, who had been engaged since 1840 in missionary work north of the Orange. In 1849 Livingstone crossed the Kalahari Desert from south to north and reached Lake Ngami, and between 1851 and 1856 he traversed the continent from west to east, making known the great waterways of the upper Zambezi. During these journeyings Livingstone "discovered", November 1855, the famous Victoria Falls, so named after the Queen of the United Kingdom. These falls are called Mosi-oa-Tunya by Africans. In 1858–1864 the lower Zambezi, the Shire and Lake Nyasa were explored by Livingstone, Nyasa having been first reached by the confidential slave of Antonio da Silva Porto, a Portuguese trader established at Bihe in Angola, who crossed Africa during 1853–1856 from Benguella to the mouth of the Rovuma. A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857–1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria. It was eventually proved to be the latter from which the Nile flowed.

Henry Morton Stanley, who had in 1871 succeeded in finding and succouring Livingstone, started again for Zanzibar in 1874, and in one of the most memorable of all exploring expeditions in Africa circumnavigated Victoria Nyanza and Tanganyika, and, striking farther inland to the Lualaba, followed that river down to the Atlantic Ocean—reached in August 1877—and proved it to be the Congo.

Explorers were also active in other parts of the continent. Southern Morocco, the Sahara and the Sudan were traversed in many directions between 1860 and 1875 by Gerhard Rohlfs, Georg Schweinfurth and Gustav Nachtigal. These travellers not only added considerably to geographical knowledge, but obtained invaluable information concerning the people, languages and natural history of the countries in which they sojourned. Among the discoveries of Schweinfurth was one that confirmed the Greek legends of the existence beyond Egypt of a "pygmy race". But the first western discoverer of the pygmies of Central Africa was Paul du Chaillu, who found them in the Ogowe district of the west coast in 1865, five years before Schweinfurth's first meeting with them; du Chaillu having previously, as the result of journeys in the Gabon region between 1855 and 1859, made popular in Europe the knowledge of the existence of the gorilla, perhaps the gigantic ape seen by Hanno the Carthaginian, and whose existence, up to the middle of the 19th century, was thought to be as legendary as that of the Pygmies of Aristotle.

Partition among European powers

Main article: Scramble for AfricaIn the last quarter of the 19th century the map of Africa was transformed. Lines of partition, drawn often through trackless African countryside, marked out the "possessions" of Germany, France, Britain and the other Great Powers. Railways penetrated the interior, vast areas were "opened up" to European conquest.

The causes which led to the partition of Africa can be found in the economic and political state of western Europe at the time. Germany, recently united under Prussian rule as the result of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, was seeking new outlets for her energies, new markets for her growing industries, and with the markets, colonies.

Germany was the last country to enter into the race to acquire colonies, and when Bismarck—the German Chancellor —acted, Africa was the only field left to exploit. South America was widely considered the fiefdom of the United States based on the Monroe Doctrine, while Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain had already divided much of Asia and the rest of the world between themselves.

Part of the reason Germany began to expand into the colonial sphere at this time, despite Bismarck's lack of enthusiasm for the idea, was a shift in the world view of the Prussian governing elite. Indeed, European elites as a whole began to view the world as a finite place, one in which only the strong would predominate. The influence of social-Darwinism was deep, encouraging a view of the world as essentially characterized by zero-sum relationships.

For different reasons the war of 1870 was also the starting-point for France in the building up of a new colonial empire. In her endeavour to regain the position lost in that war France had to look beyond Europe. To the two causes mentioned must be added others. Britain and Portugal, when they found their interests threatened, bestirred themselves, while Italy also conceived it necessary to become an African power.

It was not, however, the action of any of the great powers of Europe which precipitated the struggle. This was brought about by the projects of Léopold II, king of the Belgians. The discoveries of Livingstone, Stanley and others had aroused especial interest among two classes of men in western Europe, one the manufacturing and trading class, which saw in Central Africa possibilities of commercial exploitation, the other the philanthropic and missionary class, which beheld in the newly discovered lands millions of "savages" to Christianize and "civilize". The possibility of utilizing both these classes in the creation of a vast private estate, of which he should be the head, formed itself in the mind of Léopold II even before Stanley had navigated the Congo. The king's action proved successful; but no sooner was the nature of his project understood in Europe than it provoked the rivalry of France and Germany, and thus the international struggle was begun.

Conflicting ambitions of the European powers

Bargash Sayyid, the Sultan of Zanzibar, abolished the slave trade in Zanzibar in 1876 under pressure from Sir John Kirk of the United Kingdom.

The part of the continent to which King Léopold directed his energies was the equatorial region. In September 1876 he took what may be described as the first definite step in the modern partition of the continent. He summoned to a conference at Brussels representatives of Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Russia, to deliberate on the best methods to be adopted for the exploration and Westernization of Africa, and the opening up of the interior of the continent to commerce and industry. The conference was entirely unofficial. The delegates who attended neither represented nor pledged their respective governments. Their deliberations lasted three days and resulted in the foundation of "The International African Association," with its headquarters at Brussels. It was further resolved to establish national committees in the various countries represented, which should collect funds and appoint delegates to the International Association. The central idea appears to have been to put the exploration and development of Africa upon an international footing. But it quickly became apparent that this was an unattainable ideal. The national committees were soon working independently of the International Association, and the Association itself passed through a succession of stages until it became purely Belgian in character, and at last developed into the Congo Free State, under the personal sovereignty of King Léopold.

After the First Boer War, a conflict between the British Empire and the Boer South African Republic (Transvaal Republic), the peace treaty on March 23, 1881 gave the Boers self-government in the Transvaal under a theoretical British oversight.

For some time before 1884 there had been growing up a general conviction that it would be desirable for the powers who were interesting themselves in Africa to come to some agreement as to "the rules of the game," and to define their respective interests so far as that was practicable. Lord Granville's ill-fated treaty brought this sentiment to a head, and it was agreed to hold an international conference on African affairs.

Berlin Conference

Main article: Berlin ConferenceFrom 1885 the scramble among the powers went on with renewed vigour, and in the fifteen years that remained of the century the work of partition, so far as international agreements were concerned, was practically completed.

- Relationship to "Victorian Era" in the UK.

Soldiers of King Menelik II fended off the Italians, keeping Ethiopia independent from European colonization.

No African countries were consulted during the partitioning of Africa. An "International treaty" was signed that disregarded the ethnic, social and economic composition of the people that lived in that area. This was to resurface years later, as ethnic or "tribal" conflict after the African countries gained their independence.

20th century: 1900-1945

Africa at the start of the 20th century

All of the continent was claimed by European powers, except for Ethiopia ("Abyssinia") and Liberia.

The European powers set up a variety of different administrations in Africa at this time, with different ambitions and degrees of power. In some areas, parts of British West Africa for example, colonial control was tenuous and intended for simple economic extraction, strategic power, or as part of a long term development plan.

In other areas Europeans were encouraged to settle, creating settler states in which a European minority came to dominate society. Settlers only came to a few colonies in sufficient numbers to have a strong impact. British settler colonies included British East Africa, now Kenya, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, later Zambia and Zimbabwe, and South Africa, which already had a significant population of European settlers, the Boers.

In the Second Boer War, between the British Empire and the two Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal Republic), the Boers unsuccessfully resisted absorption in to the British Empire.

France planned to settle Algeria and eventually incorporate it into the French state as an equal to the European provinces. Its proximity across the Mediterranean allowed plans of this scale.

In most areas colonial administrations did not have the manpower or resources to fully administer the territory and had to rely on local power structures to help them. Various factions and groups within the societies exploited this European requirement for their own purposes, attempting to gain a position of power within their own communities by cooperating with Europeans. One aspect of this struggle included what Terence Ranger has termed the "invention of tradition." In order to legitimize their own claims to power in the eyes of both the colonial administrators, and their own people, people would essentially manufacture "traditional" claims to power, or ceremonies. As a result many societies were thrown into disarray by the new order.

During World War I the British and German Empires battled on several occasions, the most notable being the Battle of Tanga, and a sustained guerrilla campaign by the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck.

Interbellum

After World War I the formerly German colonies in Africa were taken over by France and the United Kingdom.

During this era a sense of local patriotism or nationalism took deeper root among African intellectuals and politicians. Some of the inspiration for this movement came from the First World War in which European countries had relied on colonial troops for their own defence. Many in Africa realized their own strength with regard to the colonizer for the first time. At the same time, some of the mystique of the "invincible" European was shattered by the barbarities of the war. However, in most areas European control remained relatively strong during this period.

Italy, under the government of Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopia, the last independent African nation, in 1935 and occupied the country until 1941.

Postcolonial era: 1945 to 1993

Decolonization

The Decolonization in Africa started with Libya in 1951. (Although Liberia, South Africa, Egypt and Ethiopia were already independent.) Many countries followed in the 50s and 60s, with a peak in 1960 with independence of a large part of French West Africa. Most of the remaining countries gained independence throughout the 1960s, although some colonizers (Portugal in particular) were reluctant to relinquish sovereignty, resulting in bitter wars of independence which lasted for a decade or more. The last African countries to gain formal independence were Guinea-Bissau from Portugal in 1974, Mozambique from Portugal in 1975, Angola from Portugal in 1975, Djibouti from France in 1977, and Namibia from South Africa in 1990. Eritrea later split off from Ethiopia in 1993.

Because many cities were founded, enlarged and renamed by the Europeans, after independence many place names (for example Stanleyville, Léopoldville, Rhodesia) were renamed: see historical African place names for these.

East Africa

Main article: East AfricaThe Mau Mau Rebellion took place in Kenya from 1952 until 1956, but was put down by British and local forces. A State of Emergency remained in place until 1960. Kenya became independent in 1963, and Jomo Kenyatta served as its first president.

The early 1990s also signaled the start of major clashes between the Hutus and the Tutsis in Rwanda and Burundi. In 1994 this culminated in the Rwandan Genocide, a conflict in which over one million people were murdered.

North Africa

Main article: North AfricaIn 1954 Gamal Abdel Nasser deposed the monarchy on Egypt and came to power. Muammar al-Qaddafi led a coup in Libya in 1969 and has remained in power.

Egypt was involved in several wars against Israel, and was allied with other Arab countries. The first was right after the Israel was founded, in 1947. Egypt went to war again in 1967 and lost the Sinai Peninsula to Israel. They went to war yet again in 1973. In 1979 Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin signed the Camp David Accords, which gave back the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt in exchange for the recognition of Israel. The accords are still in effect today. In 1981 Sadat was assassinated by an Islamist for signing the accords.

Southern Africa

Main article: Southern AfricaIn 1948 the apartheid laws were started in South Africa by the dominant party, the National Party, under the auspices of Verwoerd. These were largely a continuation of existing policies, e.g. the Land Act of 1913. The difference was the policy of "separate development;" Where previous policies had only been disparate efforts to economically exploit the African Majority, Apartheid represented an entire philosophy of separate racial goals, leading to both the divisive laws of 'petty apartheid,' and the grander scheme of African Homelands.

In 1994 the South African government abolished Apartheid. South Africans elected Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress in the country's first multiracial presidential election.

West Africa

Main article: History of West AfricaFollowing World War II, nationalist movements arose across West Africa, most notably in Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah. In 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan colony to achieve its independence, followed the next year by France's colonies; by 1974, West Africa's nations were entirely autonomous. Since independence, many West African nations have been plagued by corruption and instability, with notable civil wars in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Côte d'Ivoire, and a succession of military coups in Ghana and Burkina Faso. Many states have failed to develop their economies despite enviable natural resources, and political instability is often accompanied by undemocratic government.

References

- Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.167.

- O'Brien, Patrick K. (General Editor). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. pp.22-23

- O'Brien, Patrick K. (General Editor). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. pp.22-23

- Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.100.

- Diamond, Jared. (1999) "Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York:Norton, pp.126-127.

- Martin and O'Meara. "Africa, 3rd Ed." Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1995. http://princetonol.com/groups/iad/lessons/middle/history1.htm#Irontechnology

- O'Brien, Patrick K. (General Editor). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. pp.22-23

- July, Robert, Pre-Colonial Africa, 1975, Charles Scribners and Sons, New York, p. 60-61

- Peter N. Stearns and William Leonard Langer. The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged, 2001. Page 593.

Bibliography

- Clark, J. Desmond, The Prehistory of Africa, Thames and Hudson, 1970

- Davidson, Basil, The African Past, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1966 (1964)

- Freund, Bill, The Making of Contemporary Africa, Lynne Rienner, Boulder, 1998. Included in this book is a substantial "Annotated Bibliography" pp. 269-316.

- Shillington, Kevin, History of Africa, St. Martin's, New York, 1995 (1989)

- UNESCO, General History of Africa 8 volumes, 1980-1994

See also

- Economic history of Africa

- African archaeology

- History by continent

- Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures

- Legends of Africa

- Ogaden War

- Angolan Civil War

- Congo-Brazzaville

- Pan-Africanism

- Central Africa

- Deutsches Afrika Korps

- Second Battle of El Alamein

- North African Campaign

- Western Desert Campaign

- North African Campaign timeline

- East African Campaign (World War II)

- Afrika Korps

- Panzer Army Africa

- László Almásy Explorer, long range desert specialist and the basis of the English Patient. Discovered the Magyarab tribe of Nubai.

| History of Africa | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories |

|

Template:Africafooter Template:History by continent footer

Category: