| Revision as of 21:50, 12 July 2005 view source130.199.3.2 (talk) →5-band axial resistors: note temp coeff.← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:35, 14 July 2005 view source 80.212.238.162 (talk) →Preferred valuesNext edit → | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

| : brown 1%. | : brown 1%. | ||

| Closer tolerance resistors, called ''precision resistors'', are also available. | Closer tolerance resistors, called ''precision resistors'', are also available. | ||

| It's worth mentioning that after production, resistors intended to be of a certain value are measured and then sorted into groups depending of how | |||

| much the actual value differs from the intended. Each of these groups will then be assigned a ] accordingly. | |||

| So if you buy 100 ohms resistors with a tolerance of +/- 5%, you're unlikely to get resistors ranging from 95 to 105 ohms, with most just | |||

| around 100 ohms, as you would expect... instead, all your resistors will be just a bit over 95 or a bit under 105 ohms. Any resistors that | |||

| hit closer to the mark, would be marked as being of a higher precision (and priced accordingly). | |||

| ==Non-ideal characteristics== | ==Non-ideal characteristics== | ||

Revision as of 22:35, 14 July 2005

A resistor is a two-terminal electrical component that creates an electrical potential difference across its terminals that is proportional to the current passing through it. The ratio of potential difference (also called voltage) to current is known as its electrical resistance (or simply resistance).

In an ideal resistor, the resistance remains constant regardless of the applied voltage or current flowing through the device or the rate of change of the current. While real resistors cannot attain this perfect goal, they are designed to present little variation in electrical resistance when subjected to these changes, or to changing temperature and other environmental factors.

The SI unit of electrical resistance is the ohm. A component has a resistance of 1 ohm if a voltage of 1 volt across the component results in a current of 1 ampere, or amp, which is equivalent to a flow of one coulomb of electrical charge (approximately 6.241506 × 10 electrons) per second.

Types of resistor

Resistors may be fixed or variable. Variable resistors are also called potentiometers or rheostats (see below) and allow the resistance of the device to be altered by turning a shaft or sliding a control.

Some resistors are long and thin, with the actual resisting material in the centre, and a conducting metal leg on each end. This is called an axial package. The photo below right shows a row of commonly used resistors in a bandolier. Resistors used in computers and other devices are typically much smaller, often in surface-mount packages without leads. Larger power resistors come in sturdier packages designed to dissipate heat efficiently, but they are all basically the same structure.

Resistors are used as part of electrical networks and incorporated into microelectronic semiconductor devices.

Any physical object is a kind of resistor. Most metals are conductors, and have low resistance to the flow of electricity. The human body, a piece of plastic, or even a vacuum has a resistance that can be measured. Materials that have very high resistance are called insulators.

Resistors packaged in a bandolier

Ohm's law

The relationship between voltage, current, and resistance through an object is given by a simple equation which is popularly called Ohm's Law:

where V is the voltage across the object in volts (in Europe, U), I is the current through the object in amperes, and R is the resistance in ohms. (In fact this is only a simplification of the original Ohm's law - see the article on that law for further details.) If V and I have a linear relationship -- that is, R is constant -- along a range of values, the material of the object is said to be ohmic over that range. An ideal resistor has a fixed resistance across all frequencies and amplitudes of voltage or current.

Superconducting materials at very low temperatures have zero resistance. Insulators (such as air, diamond, or other non-conducting materials) may have extremely high (but not infinite) resistance, but break down and admit a larger flow of current under sufficiently high voltage.

Power dissipation

The power dissipated by a resistor is the voltage across the resistor times the current through the resistor:

All three equations are equivalent, the last two being derived from the first by Ohm's Law.

The total amount of heat energy released per unit time is the integral of the power:

If the average power dissipated exceeds the power rating of the resistor, then the resistor will first depart from its nominal resistance, and will then be destroyed by overheating.

Calculating resistance of a conductor

The resistance of a component can be calculated from its physical characteristics. Resistance is proportional to the length of the resistor and to the material's resistivity (a physical property of the material) and inversely proportional to cross-sectional area. The equation to determine resistance of a section of material is:

is the resistivity of the material, is the length, and is the cross-sectional area. This can be extended to an integral for more complex shapes, but this simple formula is applicable to cylindrical wires and most common conductors. This value is subject to change at high frequencies due to the skin effect, which decreases the available surface area.

Preferred values

Standard resistors are manufactured in values from a few milliohms to about a gigohm; only a limited range of values called preferred values are available. In practice, the discrete component sold as a "resistor" is not a perfect resistance, as defined above. Resistors are often marked with their tolerance (maximum expected variation from the marked resistance). On color coded resistors the color of the rightmost band denotes the tolerance:

- silver 10%

- gold 5%

- red 2%

- brown 1%.

Closer tolerance resistors, called precision resistors, are also available.

It's worth mentioning that after production, resistors intended to be of a certain value are measured and then sorted into groups depending of how much the actual value differs from the intended. Each of these groups will then be assigned a tolerance accordingly. So if you buy 100 ohms resistors with a tolerance of +/- 5%, you're unlikely to get resistors ranging from 95 to 105 ohms, with most just around 100 ohms, as you would expect... instead, all your resistors will be just a bit over 95 or a bit under 105 ohms. Any resistors that hit closer to the mark, would be marked as being of a higher precision (and priced accordingly).

Non-ideal characteristics

A resistor has a maximum working voltage and current above which the resistance may change (drastically, in some cases) or the resistor may be physically damaged (burn up, for instance). Although some resistors have specified voltage and current ratings, most are rated with a maximum power which is determined by the physical size. Common power ratings for carbon composition and metal-film resistors are 1/8 watt, 1/4 watt, and 1/2 watt. Metal-film resistors are more stable than carbon resistors against temperature changes and age. Larger resistors are able to dissipate more heat because of their larger surface area. Wire-wound and sand-filled resistors are used when a high power rating is required, such as 20 watts.

Furthermore, all real resistors also introduce some inductance and capacitance, which change the dynamic behavior of the resistor from the ideal equation.

Series and parallel circuits

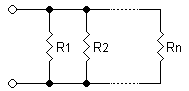

Resistors in a parallel configuration each have the same potential difference (voltage). To find their total equivalent resistance (Req):

The parallel property can be represented in equations by two vertical lines "||" (as in geometry) to simplify equations. For two resistors,

The current through resistors in series stays the same, but the voltage across each resistor can be different. The sum of the potential differences (voltage) is equal to the total voltage. To find their total resistance:

A resistor network that is a combination of parallel and series can sometimes be broken up into smaller parts that are either one or the other. For instance,

However, many resistor networks cannot be split up in this way. Consider a cube, each edge of which has been replaced by a resistor. Determining the resistance between (say) two opposite vertices requires matrix methods for the general case. However, if all twelve resistors are equal, the corner-to-corner resistance is 5/6 of any one of them.

Variable resistor

The variable resistor is a resistor whose value can be adjusted by a mechanical movement, for example by being turned by hand.

Variable resistors can be cheap single-turn types or multi-turn types with a helical element. Some even have a mechanical display to count the turns.

Traditionally, variable resistors have been unreliable, because the wire or metal would corrode or wear. Some modern variable resistors use plastic materials that do not corrode.

(Another method of control, which is not actually a resistor, but behaves like one, involves a photoelectric sensor system which measures the optical density of a piece of film. Since the sensor does not touch the film, no wear is possible.)

A rheostat is a variable resistor with two terminals, one fixed and one sliding. It is often used with high currents.

A potentiometer is a common type of variable resistor. One common use is as volume controls on audio amplifiers.

A Metal Oxide Varistor (MOV) is a special type of resistor which has 2 very different resistance values, a very high resistance at low voltage (below the trigger voltage) and very low resistance at high voltage (above the trigger voltage). It is usually used for short circuit protection in power strips or lightning bolt "arrestors" on street power poles, or as a "snubber" in back electromotive force circuits.

A thermistor is a temperature dependent resistor. There are two kinds, classified according to their temperature coefficients:

- Positive Temperature Coefficient (PTC) resistor is a resistor with a positive temperature coefficient. When the temperature rises the resistance of the PTC increases. PTC's are often found in televisions in series with the demagnetizing coil where they are used to provide a short current burst through the coil when the TV is turned on. One specialized version of a PTC is the polyswitch which acts as a self repairing fuse.

- Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) resistor is also a temperature dependent resistor, but with a negative temperature coefficient. When the temperature rises the resistance of the NTC drops. NTC's are often used in simple temperature detectors and measuring instruments.

Identifying resistors

Most axial resistors use a pattern of coloured stripes to indicate resistance. SMT ones follow a numerical pattern. Cases are usually brown, blue, or green, though other colours are occasionally found like dark red or dark gray.

4-band axial resistors

(See: Electronic color code)

4 band identification is the most commonly used colour coding scheme on all resistors. It consists of four coloured bands that are painted around the body of the resistor. The scheme is simple: The first two numbers are the first two significant digits of the resistance value, the third is a multiplier, and the fourth is the tolerance of the value. Each colour corresponds to a certain number, shown in the chart below. The tolerance for a 4-band resistor will be 2%, 5%, or 10%.

The Standard EIA Color Code Table per EIA-RS-279 is as follows:

| Colour | 1 band | 2 band | 3 band (multiplier) | 4 band (tolerance) | Temp. Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 0 | 0 | ×10 | ||

| Brown | 1 | 1 | ×10 | ±1% (F) | 100 ppm |

| Red | 2 | 2 | ×10 | ±2% (G) | 50 ppm |

| Orange | 3 | 3 | ×10 | 15 ppm | |

| Yellow | 4 | 4 | ×10 | 25 ppm | |

| Green | 5 | 5 | ×10 | ±0.5% (D) | |

| Blue | 6 | 6 | ×10 | ±0.25% (C) | |

| Violet | 7 | 7 | ×10 | ±0.1% (B) | |

| Gray | 8 | 8 | ×10 | ±0.05% (A) | |

| White | 9 | 9 | ×10 | ||

| Gold | ×0.1 | ±5% (J) | |||

| Silver | ×0.01 | ±10% (K) | |||

| None | ±20% (M) |

Note that red to violet are the colours of the rainbow where red is low energy and violet is higher energy. Resistors use specific values, which are determined by their tolerance. These values repeat for every exponent; 6.8, 68, 680, etc. This is useful because the digits, and hence the first two or three stripes, will always be similar patterns of colours, which make them easier to recognize.

5-band axial resistors

5-band identification is used for higher tolerance resistors (1%, 0.5%, 0.25%, 0.1%), to notate the extra digit. The first three bands represent the significant digits, the fourth is the multiplier, and the fifth is the tolerance.

5-band standard tolerance resistors are sometimes encountered, generally on older or specialized resistors. They can be identified by noting a standard tolerance color in the 4th band. The 5th band in this case is the temperature coefficient.

SMT resistors

Surface-mount resistors are printed with numerical values in a code related to that used on axial resistors. Standard-tolerance SMT resistors are marked with a three-digit code, in which the first two digits are the first two significant digits of the value and the third digit is the power of ten. For example, "472" represents "47" (the first two digits) multiplied by ten to the power "2" (the third digit), i.e. . Precision SMT resistors are marked with a four-digit code in which the first three digits are the first three significant digits of the value and the fourth digit is the power of ten.

See also

External links

- A good guide to resistor labeling, common values, and color codes

- Beginner's guide to potentiometers, including description of different tapers

- An article describing many aspects of resistors, including materials, tapers, and color code

- "The Original Color Coded Resistance Calculator"

- Resistor Colorcode Decoder

is the resistivity of the material,

is the resistivity of the material,  is the length, and

is the length, and  is the cross-sectional area. This can be extended to an integral for more complex shapes, but this simple formula is applicable to cylindrical wires and most common conductors. This value is subject to change at high frequencies due to the

is the cross-sectional area. This can be extended to an integral for more complex shapes, but this simple formula is applicable to cylindrical wires and most common conductors. This value is subject to change at high frequencies due to the

. Precision SMT resistors are marked with a four-digit code in which the first three digits are the first three significant digits of the value and the fourth digit is the power of ten.

. Precision SMT resistors are marked with a four-digit code in which the first three digits are the first three significant digits of the value and the fourth digit is the power of ten.