| Revision as of 23:40, 7 May 2008 editAqvilina~enwiki (talk | contribs)192 edits →References: +sv← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:29, 7 July 2008 edit undoDsp13 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers103,591 edits →References: catNext edit → | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| *Williams Obstetrics, 14th edition. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY, 1971, pages 1116-8. | *Williams Obstetrics, 14th edition. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY, 1971, pages 1116-8. | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Chamberlen, Peter}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 14:29, 7 July 2008

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Peter Chamberlen the younger" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Peter Chamberlen was the name of two brothers, the sons of William Chamberlen (about 1540 - 1596), a Huguenot surgeon who fled from Paris to England in 1576. They are famous as they discovered the modern use of obstetrical forceps. It remained a family secret for over a century.

Peter the Elder

Peter the Elder lived from 1560 to 1631 and became a surgeon and obstetrician to Queen Anne (Anne of Denmark) in London. Dunn (1999) states that he had no children but other sources suggest he had at least three ... one a daughter Hester (the wife of Thomas Cargill of Aberdeen) ... and several grandchildren, all mentioned in his will, proved in 1631.

Peter the Younger

Peter the Younger lived from 1572 to 1626 and also worked as surgeon and obstetrician. He married Sara de Laune, the daughter of a Huguenot, who lived in London. They had eight children, among them Dr. Peter Chamberlen, an obstetrician who carried on the secret use of the forceps.

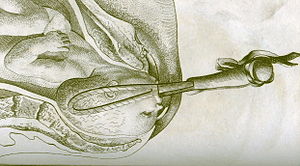

Apparently Peter the Elder was the inventor of the forceps. The brothers went to great length to keep the secret. When they arrived at the home of the woman in labor, two persons had to carry a massive box with gilded carvings into the house. The pregnant patient was blindfolded as to not to reveal the secret, all the others had to leave the room. Then the operator went to work. The people outside heard screams, bells, and other strange noises until the cry of the baby indicated another successful delivery.

The secret was kept in the family for another three generations.

Later Chamberlens

- Dr. Peter Chamberlen, also Peter the Third, born in 1601 as a son of Peter the Younger, had a good medical education and continued the tradition. He attended the birth of the future King Charles II by Queen Henrietta Maria. His attempt to create a Corporation of Midwives was opposed by the College of Physicians. He died in 1683.

- His eldest son, Hugh the elder Chamberlen (1630-?1720), also practiced obstetrics using the secret forceps. In 1670, he travelled to France and tried to sell the secret to the French government. François Mauriceau gave him a test,- to deliver a 38 year old dwarf with a grossly malformed pelvis who was in obstructed labor. He failed in this impossible task and returned to England. Hugh Chamberlen later went to the Netherlands and sold his secret to Roger Roonhuysen. The secret was sold further by the Medico-Pharmaceutical College of Amsterdam to selected physicians. After a couple of years somebody made the secret public, but only one blade of the forceps had been revealed. Hugh the Elder eventually moved to Scotland. There, in 1694, he published a book advocating health insurance.

- His son, Hugh the younger Chamberlen (1664-1728), was the last in the Chamberlen family to practice the secret use of the forceps. Toward the end of his life the design and use of the instrument entered the public domain. The first illustration of the forceps was published by Edward Hody in 1734.

References

- History of the Chamberlen family by Peter M.Dunn

- Williams Obstetrics, 14th edition. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, NY, 1971, pages 1116-8.