| Revision as of 06:05, 23 August 2005 edit205.188.116.135 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:50, 23 August 2005 edit undoWayward (talk | contribs)10,585 editsm revert edits by 205.188.116.135 to last version by 204.250.81.134Next edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| <td>II (National Park)</td></tr> | <td>II (National Park)</td></tr> | ||

| </table> | </table> | ||

| ''' |

'''Yellowstone National Park''' is a ] located in the ] of ], ], and ]. Yellowstone is the first and oldest ] in the world and covers 3,470 square miles (]), mostly in the northwest corner of Wyoming. The park is famous for its various ]s, ]s, and ] and is home to ] and ], and free-ranging herds of ] and ]. It is the core of the ], one of the largest intact ] ] remaining on the planet. | ||

| Long before any recorded ] history in |

Long before any recorded ] history in Yellowstone, a massive ] spewed an immense volume of ] that covered all of the western U.S., much of the Midwest, northern ] and some areas of the eastern Pacific Coast. The eruption dwarfed that of ] in 1980 and left a huge ] 43 miles long and 18 miles wide (70 km by 30 km) sitting over a huge magma chamber (see Geology section and ]). Yellowstone has registered three major eruption events in the last 2.2 million years with the last event occurring 640,000 years ago. Its eruptions are the largest known to have occurred on Earth within that timeframe, producing drastic climate change in the aftermath. | ||

| The park was named for the |

The park was named for the yellow rocks seen in the ]—a deep gash in the Yellowstone Plateau that was formed by floods during previous ]s and by ] erosion from the ]. | ||

| ==Human history== | ==Human history== | ||

| The human history of the park dates back 12,000 years. It was known to the original natives as "Mitzi-a-dazi," the "River of |

The human history of the park dates back 12,000 years. It was known to the original natives as "Mitzi-a-dazi," the "River of Yellow Rocks," because of the hydrothermally altered ]-containing yellow rocks in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (many people incorrectly believe that the yellow color is from ]). | ||

| The ]s that hunted and fished in the |

The ]s that hunted and fished in the Yellowstone region also utilized the significant amounts of ] found in the park to make cutting tools and weapons. In fact, ]s made of Yellowstone obsidian have been found as far away as the ], which strongly indicate that a regular ] existed between Yellowstone Native Americans and tribes further east. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In 1806 a member of the ] named ] left the Expedition to join a group of fur trappers and was probably the first non-Native American to visit the region and make contact with the Native Americans there. After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with Crow and Blackfoot tribes, he gave a description of a place of "fire and brimstone" that was dismissed by most people as delirium. The supposedly imaginary place was nicknamed "Colter's Hell." | In 1806 a member of the ] named ] left the Expedition to join a group of fur trappers and was probably the first non-Native American to visit the region and make contact with the Native Americans there. After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with Crow and Blackfoot tribes, he gave a description of a place of "fire and brimstone" that was dismissed by most people as delirium. The supposedly imaginary place was nicknamed "Colter's Hell." | ||

| Mountain man ] later returned from an 1857 expedition to the park's area and told tales of boiling springs, spouting water, a mountain of glass and |

Mountain man ] later returned from an 1857 expedition to the park's area and told tales of boiling springs, spouting water, a mountain of glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored, however, because Bridger was known for being a "spinner of yarns." Nonetheless his stories did arouse the interest of explorer and geologist ] who in 1859 started a two-year survey of the upper ] region with Bridger as a guide and with ] surveyor ]. The party was able to reach the approaches to the Yellowstone region but was not able to go any further due to heavy snows. The intervening ] stopped all attempts to explore the region, and Hayden would not be able to fulfill his mission to explore the area for another 11 years. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| A party of ]ns then organized the ], headed by the surveyor-general of Montana ]. Amongst the group was ], who would later become known as "National Park" Langford, and an Army detachment commanded by Lt. ]. The expedition spent about a month in 1870 exploring the region, collecting specimens and naming sites of interest. | A party of ]ns then organized the ], headed by the surveyor-general of Montana ]. Amongst the group was ], who would later become known as "National Park" Langford, and an Army detachment commanded by Lt. ]. The expedition spent about a month in 1870 exploring the region, collecting specimens and naming sites of interest. | ||

| In 1871 Hayden led a second, larger expedition, which was now government sponsored, to the |

In 1871 Hayden led a second, larger expedition, which was now government sponsored, to the Yellowstone region. He compiled a comprehensive report on Yellowstone which included large-format photographs by ] and paintings by ]. This report helped to convince the ] to withdraw this region from public auction. Then on ], ], President ] signed a bill into law that created Yellowstone National Park. | ||

| Langford then served for five years without pay as the first superintendent of the park and was followed by several other superintendents (who worked with some minimal funding). The second superintendent was ] who essentially volunteered for the position, after traveling through |

Langford then served for five years without pay as the first superintendent of the park and was followed by several other superintendents (who worked with some minimal funding). The second superintendent was ] who essentially volunteered for the position, after traveling through Yellowstone and witnessing its problems first hand. During his tenure Congress finally began to give the superintendent a salary and minimal funds to operate the park. He used these monies to expand access to and further explore Yellowstone. Norris also hired ] (nicknamed "Rocky Mountain Harry") to control poaching and vandalism in the park. Today, Harry Yount is considered the very first national park ranger. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Three additional superintendents followed, but none proved effective in stopping the destruction of |

Three additional superintendents followed, but none proved effective in stopping the destruction of Yellowstone's natural resources. | ||

| This continued until 1886 when the Army was given the task of managing the park (see ]). The Army remained the steward of the park until control was given to a civilian corps of rangers under the newly created ] in 1916. | This continued until 1886 when the Army was given the task of managing the park (see ]). The Army remained the steward of the park until control was given to a civilian corps of rangers under the newly created ] in 1916. | ||

| More recently, |

More recently, Yellowstone has been designated as an ] on ], ], and a ] ] on ], ]. | ||

| == Forest Fires == | == Forest Fires == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| A series of ]-derived ]s started to burn large portions of the park in ] of the especially dry summer of 1988. Thousands of ]s responded to the blaze in order to prevent human-built structures from succumbing to the flames. Controversially, however, no serious effort was made to completely extinguish the fires, and they burned until the arrival of autumn rains. Ecologists argued that fire is part of the |

A series of ]-derived ]s started to burn large portions of the park in ] of the especially dry summer of 1988. Thousands of ]s responded to the blaze in order to prevent human-built structures from succumbing to the flames. Controversially, however, no serious effort was made to completely extinguish the fires, and they burned until the arrival of autumn rains. Ecologists argued that fire is part of the Yellowstone ] and that not allowing the fires to run their course (as has been the practice in the past) will result in a choked, sick and decaying forest. In fact, relatively few ] in the park were killed by the fires and since the blaze many saplings have sprung up on their own, old vistas were viewable once again and many previously unknown archaeological and geological sites of interest were found and cataloged by scientists. The National Park Service now has a policy of lighting smaller, controlled "]" to prevent another dangerous buildup of flammable materials. | ||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| The ] of ] runs roughly diagonally through the southwestern part of the park. The divide is a ] ridgeline that bisects the continent between ] and ] water drainages (the drainage from one-third of the park is on the Pacific side of this divide). | The ] of ] runs roughly diagonally through the southwestern part of the park. The divide is a ] ridgeline that bisects the continent between ] and ] water drainages (the drainage from one-third of the park is on the Pacific side of this divide). | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| For example, the ] and the ] both have their origin close to each other in the park. However, the headwaters of the Snake River are on the west side of the continental divide, and the headwaters of the |

For example, the ] and the ] both have their origin close to each other in the park. However, the headwaters of the Snake River are on the west side of the continental divide, and the headwaters of the Yellowstone River are on the east side of that divide. The result is that the waters of the Snake River head toward the Pacific Ocean, and the waters of the Yellowstone head for the Atlantic Ocean (via the ]). | ||

| The park sits on a high ] which is, on average, 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above ] and is bounded on nearly all sides by ]s of the ], which range from 10,000 to 14,000 feet (3,000 to 4,300 m) in elevation. These ranges are: the ] (to the northwest), ] (to the north), ] (to the east), ] (southeast corner), ] (to the south, see ]) and the ] (to the west). The most prominent summit in the plateau is ] at 10,243 feet (3,122 m). | The park sits on a high ] which is, on average, 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above ] and is bounded on nearly all sides by ]s of the ], which range from 10,000 to 14,000 feet (3,000 to 4,300 m) in elevation. These ranges are: the ] (to the northwest), ] (to the north), ] (to the east), ] (southeast corner), ] (to the south, see ]) and the ] (to the west). The most prominent summit in the plateau is ] at 10,243 feet (3,122 m). | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

| Just outside of the southwestern park border is the ], which is a plateau ringed by low hills. Beyond that is the ]s of southern ], which are covered by ]s and slope gently to the southwest (see ]). | Just outside of the southwestern park border is the ], which is a plateau ringed by low hills. Beyond that is the ]s of southern ], which are covered by ]s and slope gently to the southwest (see ]). | ||

| The major feature of the |

The major feature of the Yellowstone Plateau is the ]; a very large ] which has been nearly filled-in with ] debris and measures about 60 kilometers long by about 50 kilometers wide (40 by 30 mi.). Within this caldera lies most of ], which is the largest high-elevation lake in North America, and two ]s, which are areas that are uplifting at a slightly faster rate than the rest of the plateau. <br clear="all"> | ||

| ==Geology== | ==Geology== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Yellowstone is at the northeast tip of a smooth U-shaped curve through the mountains, which is now the ]. This curved ] was created as the North American ] drifted across a stationary volcanic ] beneath the ]'s crust. This hot spot used to be near what is now ], but North America has drifted at a rate of 4.5 ]s a year in a southwestern direction, shifting the hot spot to its present location. | |||

| ] is the largest volcanic system in ]. It has been termed a "]" because the ] was formed by exceptionally large explosive eruptions. It was created by a cataclysmic eruption that occurred 640,000 years ago that released 1,000 ]s of ], rock and ] materials (this was 800 times larger than ]' 1980 eruption), forming a ] nearly a ] deep and 70 by 40 kilometres in size (45 by 25 mi.) (the size of the caldera has been modified a bit since this time and has mostly been filled in, however). The ] ] created by this eruption is called the ]. In addition to the last great eruptive cycle there were two other previous ones in the |

] is the largest volcanic system in ]. It has been termed a "]" because the ] was formed by exceptionally large explosive eruptions. It was created by a cataclysmic eruption that occurred 640,000 years ago that released 1,000 ]s of ], rock and ] materials (this was 800 times larger than ]' 1980 eruption), forming a ] nearly a ] deep and 70 by 40 kilometres in size (45 by 25 mi.) (the size of the caldera has been modified a bit since this time and has mostly been filled in, however). The ] ] created by this eruption is called the ]. In addition to the last great eruptive cycle there were two other previous ones in the Yellowstone area. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Each eruption is in fact a part of an eruptive cycle that climaxes with the collapse of the roof of a partially emptied ]. This creates a crater, called a caldera, and releases vast amounts of volcanic material (usually through fissures that ring the caldera). The time between the last three cataclysmic eruptions in the |

Each eruption is in fact a part of an eruptive cycle that climaxes with the collapse of the roof of a partially emptied ]. This creates a crater, called a caldera, and releases vast amounts of volcanic material (usually through fissures that ring the caldera). The time between the last three cataclysmic eruptions in the Yellowstone area has ranged from 600,000 to 900,000 years, but the small number of such climax eruptions can not be used to make a prediction for the time range for the next climax eruption. | ||

| The first and largest eruption climaxed to the southwest of the current park boundaries 2.2 million years ago and formed a caldera about 80 by 50 kilometres in size (50 by 30 mi.) and hundreds of meters deep after releasing 2,500 cubic kilometers of material (mostly ash, ] and other pyroclastics). ] This caldera has been filled in by subsequent eruptions, and the geologic formation created by this eruption is called the ]. The second eruption, at 280 km³ of material ejected, climaxed 1.2 million years ago and formed the much smaller ] and the geologic formation called the ]. All three climax eruptions released vast amounts of ash that blanketed much of central North America and fell many hundreds of miles away (as far as California to the southwest; see ]). The amount of ash and gases released into the atmosphere probably caused significant impacts to world weather patterns and led to the ] of many species in at least North America. About 160,000 years ago a much smaller climax eruption occurred which formed a relatively small caldera that is now filled in with the West Thumb of ]. | The first and largest eruption climaxed to the southwest of the current park boundaries 2.2 million years ago and formed a caldera about 80 by 50 kilometres in size (50 by 30 mi.) and hundreds of meters deep after releasing 2,500 cubic kilometers of material (mostly ash, ] and other pyroclastics). ] This caldera has been filled in by subsequent eruptions, and the geologic formation created by this eruption is called the ]. The second eruption, at 280 km³ of material ejected, climaxed 1.2 million years ago and formed the much smaller ] and the geologic formation called the ]. All three climax eruptions released vast amounts of ash that blanketed much of central North America and fell many hundreds of miles away (as far as California to the southwest; see ]). The amount of ash and gases released into the atmosphere probably caused significant impacts to world weather patterns and led to the ] of many species in at least North America. About 160,000 years ago a much smaller climax eruption occurred which formed a relatively small caldera that is now filled in with the West Thumb of ]. | ||

| Lava strata is most easily seen at the Grand Canyon of the |

Lava strata is most easily seen at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone where the Yellowstone River continues to carve into the ancient lava flows. According to Ken Pierce, ] geologist, at the end of the last glacial period, about 14,000 to 18,000 years ago, ]s formed at the mouth of ]. When the ice dams melted, a great volume of water was released downstream causing massive ]s and immediate and catastrophic erosion of the present-day canyon. These flash floods probably happened more than once. The canyon is a classic ], indicative of river-type erosion rather than glaciation. Today the canyon is still being eroded by the Yellowstone River. | ||

| After the last major climax eruption 630,000 years ago until about 70,000 years ago, |

After the last major climax eruption 630,000 years ago until about 70,000 years ago, Yellowstone Caldera was nearly filled in with periodic eruptions of ] lavas (example at ]) and ]ic lavas (example at ]). ], ''Yellowstone National Park'']]But 150,000 years ago the floor of the plateau began to bulge up again. Two areas in particular at the foci of the elliptically shaped caldera are rising faster than the rest of the plateau. This differential in uplift has created two ]s (] and ]) which are uplifting at 15 ]s a year while the rest of the caldera area of the plateau is uplifting at 12.5 millimeters a year. | ||

| Preserved within |

Preserved within Yellowstone are many ] features and some 10,000 ]s and ], 62% of the planet's known total. The superheated water that sustains these features comes from the same hot spot described above. The most famous geyser in the park, and perhaps the world, is ] (located in Upper Geyser Basin), but the park also contains the largest active geyser in the world, ] (in Norris Geyser Basin; see ''']'''). | ||

| <br clear="all"> | <br clear="all"> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In 2003 notable changes occurred in thermal activity resulting in the closure of certain areas of the park. Other findings included a bulge that had appeared beneath ]. On ], ], a biologist discovered 5 dead bison which had inhaled an apparent release of toxic geothermal gases. Shortly after in April 2004 the park experienced an upsurge of earthquake activity. Scientists are undecided on how to interpret these recent events. The ] government responded by allocating more resources to monitor the caldera and asking visitors to remain on designated safe trails. | In 2003 notable changes occurred in thermal activity resulting in the closure of certain areas of the park. Other findings included a bulge that had appeared beneath ]. On ], ], a biologist discovered 5 dead bison which had inhaled an apparent release of toxic geothermal gases. Shortly after in April 2004 the park experienced an upsurge of earthquake activity. Scientists are undecided on how to interpret these recent events. The ] government responded by allocating more resources to monitor the caldera and asking visitors to remain on designated safe trails. | ||

| ==Biology and ecology== | ==Biology and ecology== | ||

| ''Main articles'': ], ] | ''Main articles'': ], ] | ||

| The dominant tree species in the park is ], however, varieties of ], ] and ] are also common. There are at least 600 species of trees and plants found in the park, some of which are found nowhere else. | The dominant tree species in the park is ], however, varieties of ], ] and ] are also common. There are at least 600 species of trees and plants found in the park, some of which are found nowhere else. | ||

| Yellowstone is widely considered to be the finest ] wildlife habitats in the ]. Animals found in the park include the majestic ] (buffalo), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] (puma). The ] is a highly sought after trophy fish by ] yet has been threatened in recent years by the suspicious introduction of ] that compete for spawning grounds and are known to consume smaller cutthroat trout. | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| The relatively large bison populations that exist in the park are a concern for ranchers who fear that the bison can transmit ] diseases to their domesticated cousins. In fact, about half of |

The relatively large bison populations that exist in the park are a concern for ranchers who fear that the bison can transmit ] diseases to their domesticated cousins. In fact, about half of Yellowstone's bison have been exposed to ], a ]l disease that came to ] with ]an cattle and may cause ] to ]. The disease has little effect on park bison and no reported case of transmission from wild bison to a visitor or to domestic livestock has ever been filed. But since the possibility of contagion still exists, the State of Montana believes its "brucellosis-free" status may be jeopardized if bison are in proximity to cattle. Montana has approved a bison hunt for fall of 2005, with 50 licenses issued to shoot bison that have left the park. ] also carry the disease, but this popular game species is not considered a threat to livestock. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| To combat the perceived threat, National Park personnel regularly harass bison herds back into the park when they venture outside of park borders. ] activists state that is a cruel practice and that the possibility for disease transmission is not as great as some ranchers maintain. Ecologists also point out that the bison are just traveling to seasonal grazing areas that lie within the Greater |

To combat the perceived threat, National Park personnel regularly harass bison herds back into the park when they venture outside of park borders. ] activists state that is a cruel practice and that the possibility for disease transmission is not as great as some ranchers maintain. Ecologists also point out that the bison are just traveling to seasonal grazing areas that lie within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that have been converted to cattle grazing (most of these areas are also within ]). | ||

| ] | ] | ||

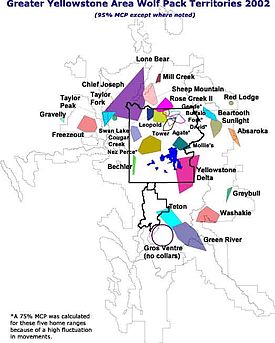

| A controversial decision by the ] (which oversees threatened and endangered species), is the recent reintroduction of ] into the park's ecosystem. For many years the wolves were hunted and harassed until they become locally extinct in the 1930s. The smaller cousin of the wolf, the ], then became the park's top predator. However, the coyote is not able to bring down any large animal in the park and the result of this lack of a top predator on these populations was a marked increase in lame and sick megafauna. Since the reintroduction of wolves in the late 1990s this trend has started to reverse. However, ranchers in surrounding areas are concerned about wolves that venture outside the park and prey on their livestock, especially ] and ]. For the most part, wolves kill what they were taught to kill as pups, so they tend to prey on elk rather than sheep, but once a wolf pack begins eating sheep and training the pups to eat sheep, there is little recourse but to destroy the offending pack members. Ranchers are compensated for their losses if they can prove that wolves killed the livestock, but they contend that it is often difficult to prove that the kills were not made by coyotes or wild dogs. Reintroduced wolf packs do not carry ] status, allowing ranchers to kill wolves that threaten their herds, but wolves relocating from Canada on their own have begun to merge with the |

A controversial decision by the ] (which oversees threatened and endangered species), is the recent reintroduction of ] into the park's ecosystem. For many years the wolves were hunted and harassed until they become locally extinct in the 1930s. The smaller cousin of the wolf, the ], then became the park's top predator. However, the coyote is not able to bring down any large animal in the park and the result of this lack of a top predator on these populations was a marked increase in lame and sick megafauna. Since the reintroduction of wolves in the late 1990s this trend has started to reverse. However, ranchers in surrounding areas are concerned about wolves that venture outside the park and prey on their livestock, especially ] and ]. For the most part, wolves kill what they were taught to kill as pups, so they tend to prey on elk rather than sheep, but once a wolf pack begins eating sheep and training the pups to eat sheep, there is little recourse but to destroy the offending pack members. Ranchers are compensated for their losses if they can prove that wolves killed the livestock, but they contend that it is often difficult to prove that the kills were not made by coyotes or wild dogs. Reintroduced wolf packs do not carry ] status, allowing ranchers to kill wolves that threaten their herds, but wolves relocating from Canada on their own have begun to merge with the Yellowstone population, making it difficult to discern which wolves are protected and which are not. The National Park Service was generally not in favor of the reintroduction citing evidence that wolves had already begun to return on their own, reestablishing themselves in very limited numbers prior to the wolf reintroduction. Wildlife biologists employed by the National Park Service had documented rare sightings made personally and from eyewitness accounts. It was a quiet concern that the compact agreed on by federal agencies and the states in which Yellowstone is located would ultimately provide less protection to the wolf since the threatened status would be amended to appease local interests such as ranchers who would not likely face prosecution under the reintroduction agreement. | ||

| ==Tourist information== | ==Tourist information== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Yellowstone is one of the most popular national parks in the United States. The park is unique in that it features multiple natural wonders all in the same park. | |||

| Geysers, hot springs, a grand canyon, forests, wilderness, wildlife and even a large lake can all be found inside the park. Due to the park's diversity of features, the list of activities for visitors is nearly endless. From backpacking to mountaineering, from ]ing to ], from sightseeing to watching bison, moose, and elk wandering into the parking lot of the visitor centers, most visitors enjoy a memorable experience in nature. | Geysers, hot springs, a grand canyon, forests, wilderness, wildlife and even a large lake can all be found inside the park. Due to the park's diversity of features, the list of activities for visitors is nearly endless. From backpacking to mountaineering, from ]ing to ], from sightseeing to watching bison, moose, and elk wandering into the parking lot of the visitor centers, most visitors enjoy a memorable experience in nature. | ||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

| Lodging for visitors exist at 11 locations within park boundaries. There is a clear view of ] at the park's ]. Lodges range from hotel to cabin accommodations. There also are 11 campgrounds and one hard-sided recreational vehicle park. | Lodging for visitors exist at 11 locations within park boundaries. There is a clear view of ] at the park's ]. Lodges range from hotel to cabin accommodations. There also are 11 campgrounds and one hard-sided recreational vehicle park. | ||

| The park itself is surrounded by other protected lands (including ] and Custer National Forest) and beautiful drives (such as the ]). Nearby communities include ]; ]; ]; ]; and ]. | The park itself is surrounded by other protected lands (including ] and Custer National Forest) and beautiful drives (such as the ]). Nearby communities include ]; ]; ]; ]; and ]. | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Commons| |

{{Commons|Yellowstone National Park|Yellowstone National Park}} | ||

| *''Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition'', Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D. Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7 | *''Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition'', Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D. Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7 | ||

Revision as of 06:50, 23 August 2005

| Yellowstone | |

| |

| Designation | National Park |

| Location | Idaho, Wyoming and Montana |

| Nearest city | Billings, Montana |

| Coordinates | 44°40′N 110°28′W / 44.667°N 110.467°W / 44.667; -110.467 |

| Area | 2,219,799 acres 8,983.24 km² |

| Date of establishment | March 1, 1872 |

| Visitation | 2,969,868 (2002) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| IUCN category | II (National Park) |

Yellowstone National Park is a U.S. National Park located in the states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Yellowstone is the first and oldest national park in the world and covers 3,470 square miles (8,980 km²), mostly in the northwest corner of Wyoming. The park is famous for its various geysers, hot springs, and other geothermal features and is home to grizzly bears and wolves, and free-ranging herds of bison and elk. It is the core of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the largest intact temperate zone ecosystems remaining on the planet.

Long before any recorded human history in Yellowstone, a massive volcanic eruption spewed an immense volume of ash that covered all of the western U.S., much of the Midwest, northern Mexico and some areas of the eastern Pacific Coast. The eruption dwarfed that of Mount St. Helens in 1980 and left a huge caldera 43 miles long and 18 miles wide (70 km by 30 km) sitting over a huge magma chamber (see Geology section and Yellowstone Caldera). Yellowstone has registered three major eruption events in the last 2.2 million years with the last event occurring 640,000 years ago. Its eruptions are the largest known to have occurred on Earth within that timeframe, producing drastic climate change in the aftermath.

The park was named for the yellow rocks seen in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone—a deep gash in the Yellowstone Plateau that was formed by floods during previous ice ages and by river erosion from the Yellowstone River.

Human history

The human history of the park dates back 12,000 years. It was known to the original natives as "Mitzi-a-dazi," the "River of Yellow Rocks," because of the hydrothermally altered iron-containing yellow rocks in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (many people incorrectly believe that the yellow color is from sulfur).

The Native Americans that hunted and fished in the Yellowstone region also utilized the significant amounts of obsidian found in the park to make cutting tools and weapons. In fact, arrowheads made of Yellowstone obsidian have been found as far away as the Mississippi Valley, which strongly indicate that a regular obsidian trade existed between Yellowstone Native Americans and tribes further east.

In 1806 a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition named John Colter left the Expedition to join a group of fur trappers and was probably the first non-Native American to visit the region and make contact with the Native Americans there. After surviving wounds he suffered in a battle with Crow and Blackfoot tribes, he gave a description of a place of "fire and brimstone" that was dismissed by most people as delirium. The supposedly imaginary place was nicknamed "Colter's Hell."

Mountain man Jim Bridger later returned from an 1857 expedition to the park's area and told tales of boiling springs, spouting water, a mountain of glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored, however, because Bridger was known for being a "spinner of yarns." Nonetheless his stories did arouse the interest of explorer and geologist F.V. Hayden who in 1859 started a two-year survey of the upper Missouri River region with Bridger as a guide and with United States Army surveyor W.F. Raynolds. The party was able to reach the approaches to the Yellowstone region but was not able to go any further due to heavy snows. The intervening American Civil War stopped all attempts to explore the region, and Hayden would not be able to fulfill his mission to explore the area for another 11 years.

A party of Montanans then organized the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition, headed by the surveyor-general of Montana Henry Washburn. Amongst the group was Nathaniel P. Langford, who would later become known as "National Park" Langford, and an Army detachment commanded by Lt. Gustavus Doane. The expedition spent about a month in 1870 exploring the region, collecting specimens and naming sites of interest.

In 1871 Hayden led a second, larger expedition, which was now government sponsored, to the Yellowstone region. He compiled a comprehensive report on Yellowstone which included large-format photographs by William Henry Jackson and paintings by Thomas Moran. This report helped to convince the U.S. Congress to withdraw this region from public auction. Then on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a bill into law that created Yellowstone National Park.

Langford then served for five years without pay as the first superintendent of the park and was followed by several other superintendents (who worked with some minimal funding). The second superintendent was Philetus Norris who essentially volunteered for the position, after traveling through Yellowstone and witnessing its problems first hand. During his tenure Congress finally began to give the superintendent a salary and minimal funds to operate the park. He used these monies to expand access to and further explore Yellowstone. Norris also hired Harry Yount (nicknamed "Rocky Mountain Harry") to control poaching and vandalism in the park. Today, Harry Yount is considered the very first national park ranger.

Three additional superintendents followed, but none proved effective in stopping the destruction of Yellowstone's natural resources.

This continued until 1886 when the Army was given the task of managing the park (see Fort Yellowstone). The Army remained the steward of the park until control was given to a civilian corps of rangers under the newly created National Park Service in 1916.

More recently, Yellowstone has been designated as an International Biosphere Reserve on October 26, 1976, and a United Nations World Heritage Site on September 8, 1978.

Forest Fires

A series of lightning-derived fires started to burn large portions of the park in July of the especially dry summer of 1988. Thousands of firefighters responded to the blaze in order to prevent human-built structures from succumbing to the flames. Controversially, however, no serious effort was made to completely extinguish the fires, and they burned until the arrival of autumn rains. Ecologists argued that fire is part of the Yellowstone ecosystem and that not allowing the fires to run their course (as has been the practice in the past) will result in a choked, sick and decaying forest. In fact, relatively few megafauna in the park were killed by the fires and since the blaze many saplings have sprung up on their own, old vistas were viewable once again and many previously unknown archaeological and geological sites of interest were found and cataloged by scientists. The National Park Service now has a policy of lighting smaller, controlled "prescribed fires" to prevent another dangerous buildup of flammable materials.

Geography

The continental divide of North America runs roughly diagonally through the southwestern part of the park. The divide is a topographic ridgeline that bisects the continent between Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean water drainages (the drainage from one-third of the park is on the Pacific side of this divide).

For example, the Yellowstone River and the Snake River both have their origin close to each other in the park. However, the headwaters of the Snake River are on the west side of the continental divide, and the headwaters of the Yellowstone River are on the east side of that divide. The result is that the waters of the Snake River head toward the Pacific Ocean, and the waters of the Yellowstone head for the Atlantic Ocean (via the Gulf of Mexico).

The park sits on a high plateau which is, on average, 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above sea level and is bounded on nearly all sides by mountain ranges of the Middle Rocky Mountains, which range from 10,000 to 14,000 feet (3,000 to 4,300 m) in elevation. These ranges are: the Gallatin Range (to the northwest), Beartooth Mountains (to the north), Absaroka Mountains (to the east), Wind River Range (southeast corner), Teton Mountains (to the south, see Grand Teton National Park) and the Madison Range (to the west). The most prominent summit in the plateau is Mount Washburn at 10,243 feet (3,122 m).

Just outside of the southwestern park border is the Island Park Caldera, which is a plateau ringed by low hills. Beyond that is the Snake River Plains of southern Idaho, which are covered by flood basalts and slope gently to the southwest (see Craters of the Moon National Monument).

The major feature of the Yellowstone Plateau is the Yellowstone Caldera; a very large caldera which has been nearly filled-in with volcanic debris and measures about 60 kilometers long by about 50 kilometers wide (40 by 30 mi.). Within this caldera lies most of Yellowstone Lake, which is the largest high-elevation lake in North America, and two resurgent domes, which are areas that are uplifting at a slightly faster rate than the rest of the plateau.

Geology

Yellowstone is at the northeast tip of a smooth U-shaped curve through the mountains, which is now the Snake River Plain. This curved plain was created as the North American continent drifted across a stationary volcanic hot spot beneath the Earth's crust. This hot spot used to be near what is now Boise, Idaho, but North America has drifted at a rate of 4.5 centimetres a year in a southwestern direction, shifting the hot spot to its present location.

Yellowstone Caldera is the largest volcanic system in North America. It has been termed a "supervolcano" because the caldera was formed by exceptionally large explosive eruptions. It was created by a cataclysmic eruption that occurred 640,000 years ago that released 1,000 cubic kilometers of ash, rock and pyroclastic materials (this was 800 times larger than Mount St. Helens' 1980 eruption), forming a crater nearly a kilometre deep and 70 by 40 kilometres in size (45 by 25 mi.) (the size of the caldera has been modified a bit since this time and has mostly been filled in, however). The welded tuff geologic formation created by this eruption is called the Lava Creek Tuff. In addition to the last great eruptive cycle there were two other previous ones in the Yellowstone area.

Each eruption is in fact a part of an eruptive cycle that climaxes with the collapse of the roof of a partially emptied magma chamber. This creates a crater, called a caldera, and releases vast amounts of volcanic material (usually through fissures that ring the caldera). The time between the last three cataclysmic eruptions in the Yellowstone area has ranged from 600,000 to 900,000 years, but the small number of such climax eruptions can not be used to make a prediction for the time range for the next climax eruption.

The first and largest eruption climaxed to the southwest of the current park boundaries 2.2 million years ago and formed a caldera about 80 by 50 kilometres in size (50 by 30 mi.) and hundreds of meters deep after releasing 2,500 cubic kilometers of material (mostly ash, pumice and other pyroclastics).

This caldera has been filled in by subsequent eruptions, and the geologic formation created by this eruption is called the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff. The second eruption, at 280 km³ of material ejected, climaxed 1.2 million years ago and formed the much smaller Island Park Caldera and the geologic formation called the Mesa Falls Tuff. All three climax eruptions released vast amounts of ash that blanketed much of central North America and fell many hundreds of miles away (as far as California to the southwest; see Lake Tecopa). The amount of ash and gases released into the atmosphere probably caused significant impacts to world weather patterns and led to the extinction of many species in at least North America. About 160,000 years ago a much smaller climax eruption occurred which formed a relatively small caldera that is now filled in with the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake.

Lava strata is most easily seen at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone where the Yellowstone River continues to carve into the ancient lava flows. According to Ken Pierce, U.S. Geological Survey geologist, at the end of the last glacial period, about 14,000 to 18,000 years ago, ice dams formed at the mouth of Yellowstone Lake. When the ice dams melted, a great volume of water was released downstream causing massive flash floods and immediate and catastrophic erosion of the present-day canyon. These flash floods probably happened more than once. The canyon is a classic V-shaped valley, indicative of river-type erosion rather than glaciation. Today the canyon is still being eroded by the Yellowstone River.

After the last major climax eruption 630,000 years ago until about 70,000 years ago, Yellowstone Caldera was nearly filled in with periodic eruptions of rhyolitic lavas (example at Obsidian Cliffs) and basaltic lavas (example at Sheepeaters Cliff).

But 150,000 years ago the floor of the plateau began to bulge up again. Two areas in particular at the foci of the elliptically shaped caldera are rising faster than the rest of the plateau. This differential in uplift has created two resurgent domes (Sour Creek dome and Mallard Lake dome) which are uplifting at 15 millimeters a year while the rest of the caldera area of the plateau is uplifting at 12.5 millimeters a year.

Preserved within Yellowstone are many geothermal features and some 10,000 hot springs and geysers, 62% of the planet's known total. The superheated water that sustains these features comes from the same hot spot described above. The most famous geyser in the park, and perhaps the world, is Old Faithful Geyser (located in Upper Geyser Basin), but the park also contains the largest active geyser in the world, Steamboat Geyser (in Norris Geyser Basin; see Geothermal areas of Yellowstone).

In 2003 notable changes occurred in thermal activity resulting in the closure of certain areas of the park. Other findings included a bulge that had appeared beneath Yellowstone Lake. On March 10, 2004, a biologist discovered 5 dead bison which had inhaled an apparent release of toxic geothermal gases. Shortly after in April 2004 the park experienced an upsurge of earthquake activity. Scientists are undecided on how to interpret these recent events. The United States government responded by allocating more resources to monitor the caldera and asking visitors to remain on designated safe trails.

Biology and ecology

Main articles: Animals of Yellowstone, Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The dominant tree species in the park is Lodgepole pine, however, varieties of spruce, fir and aspen are also common. There are at least 600 species of trees and plants found in the park, some of which are found nowhere else.

Yellowstone is widely considered to be the finest megafauna wildlife habitats in the lower 48 states. Animals found in the park include the majestic American bison (buffalo), grizzly bear, black bear, elk, moose, mule deer, pronghorn, wolverine, bighorn sheep and mountain lion (puma). The Yellowstone Lake Cutthroat Trout is a highly sought after trophy fish by anglers yet has been threatened in recent years by the suspicious introduction of lake trout that compete for spawning grounds and are known to consume smaller cutthroat trout.

The relatively large bison populations that exist in the park are a concern for ranchers who fear that the bison can transmit bovine diseases to their domesticated cousins. In fact, about half of Yellowstone's bison have been exposed to brucellosis, a bacterial disease that came to North America with European cattle and may cause cattle to miscarry. The disease has little effect on park bison and no reported case of transmission from wild bison to a visitor or to domestic livestock has ever been filed. But since the possibility of contagion still exists, the State of Montana believes its "brucellosis-free" status may be jeopardized if bison are in proximity to cattle. Montana has approved a bison hunt for fall of 2005, with 50 licenses issued to shoot bison that have left the park. Elk also carry the disease, but this popular game species is not considered a threat to livestock.

To combat the perceived threat, National Park personnel regularly harass bison herds back into the park when they venture outside of park borders. Animal rights activists state that is a cruel practice and that the possibility for disease transmission is not as great as some ranchers maintain. Ecologists also point out that the bison are just traveling to seasonal grazing areas that lie within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that have been converted to cattle grazing (most of these areas are also within United States National Forests).

A controversial decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (which oversees threatened and endangered species), is the recent reintroduction of wolves into the park's ecosystem. For many years the wolves were hunted and harassed until they become locally extinct in the 1930s. The smaller cousin of the wolf, the coyote, then became the park's top predator. However, the coyote is not able to bring down any large animal in the park and the result of this lack of a top predator on these populations was a marked increase in lame and sick megafauna. Since the reintroduction of wolves in the late 1990s this trend has started to reverse. However, ranchers in surrounding areas are concerned about wolves that venture outside the park and prey on their livestock, especially sheep and cattle. For the most part, wolves kill what they were taught to kill as pups, so they tend to prey on elk rather than sheep, but once a wolf pack begins eating sheep and training the pups to eat sheep, there is little recourse but to destroy the offending pack members. Ranchers are compensated for their losses if they can prove that wolves killed the livestock, but they contend that it is often difficult to prove that the kills were not made by coyotes or wild dogs. Reintroduced wolf packs do not carry endangered species status, allowing ranchers to kill wolves that threaten their herds, but wolves relocating from Canada on their own have begun to merge with the Yellowstone population, making it difficult to discern which wolves are protected and which are not. The National Park Service was generally not in favor of the reintroduction citing evidence that wolves had already begun to return on their own, reestablishing themselves in very limited numbers prior to the wolf reintroduction. Wildlife biologists employed by the National Park Service had documented rare sightings made personally and from eyewitness accounts. It was a quiet concern that the compact agreed on by federal agencies and the states in which Yellowstone is located would ultimately provide less protection to the wolf since the threatened status would be amended to appease local interests such as ranchers who would not likely face prosecution under the reintroduction agreement.

Tourist information

Yellowstone is one of the most popular national parks in the United States. The park is unique in that it features multiple natural wonders all in the same park.

Geysers, hot springs, a grand canyon, forests, wilderness, wildlife and even a large lake can all be found inside the park. Due to the park's diversity of features, the list of activities for visitors is nearly endless. From backpacking to mountaineering, from kayaking to fishing, from sightseeing to watching bison, moose, and elk wandering into the parking lot of the visitor centers, most visitors enjoy a memorable experience in nature.

Due to the geothermal activities of the park, the odor of sulfur is common in certain areas of the park. Visitors with respiratory difficulties should consult their doctors before visiting.

Wildfires are a relatively common occurrence in the park, due to the dry summer climate. A series of wildfires burned out of control in 1988, destroying significant forested portions of the park, though none of the major tourist areas were affected. Some areas have only recently recovered fully from the blaze.

Park officials advise visitors not to approach dangerous animals and to stay on designated safe trails to avoid falling into boiling liquids and inhaling toxic gas. In 2004, five bison were discovered dead from an apparent inhalation of toxic geothermal gases.

Lodging for visitors exist at 11 locations within park boundaries. There is a clear view of Old Faithful Geyser at the park's Old Faithful Inn. Lodges range from hotel to cabin accommodations. There also are 11 campgrounds and one hard-sided recreational vehicle park.

The park itself is surrounded by other protected lands (including Grand Teton National Park and Custer National Forest) and beautiful drives (such as the Beartooth Highway). Nearby communities include West Yellowstone, Montana; Cody, Wyoming; Red Lodge, Montana; Ashton, Idaho; and Gardiner, Montana.

References

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D. Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

- National Park Service

- Yellowstone Park Foundation

External links

- Official site: Yellowstone National Park

- Climate data for Yellowstone National Park

- Yellowstone page on Stromboli online

- Yellowstone National Park Pictures

- Yellowstone National Park Wildland Fire Images - Fires of 1988 public domain images.

- USGS: Volcanic History of the Yellowstone Plateau Volcanic Field

- yellowstonenationalpark.com, Calderas, Glaciations

- Photographic virtual tour of Yellowstone National Park

- Buffalo Field Campaign, working to stop the slaughter of Yellowstone's wild free roaming buffalo

- h2g2 has articles about the origin of Yellowstone, its geology , its early history and European exploration.

- Yellowstone National Park - National Parks Gallery