| Revision as of 22:11, 28 August 2008 editM.K (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers13,165 edits state your probelms on talk first← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:13, 28 August 2008 edit undoPiotrus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers286,273 edits explained on talkNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{POV-title|date=December 2007}} | |||

| {{Campaign | {{Campaign | ||

| |name=Establishment of Second Polish Republic | |name=Establishment of Second Polish Republic | ||

| Line 56: | Line 54: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| After Poland acquired control of the town and its surroundings, Lithuanian schools were closed and Polish schools were opened.<ref name="Buch_ann"/> The Poles evicted the local Lithuanian clergy, which they saw as a stronghold of Lithuanian nationalism in the region; the prominent seminary in the town was relocated.<ref name="Buch_ann"/> According to Lithuanian historian ], the repressions directed at the Lithuanian population were even more widespread, with a ban on the public use of the ], closure of various Lithuanian organizations (with 1,300 members), all Lithuanian schools<ref name="Buch_ann"/> (with approx. 300 pupils), and printing presses, confiscation of property, and burning of Lithuanian books.<ref name=LKA>{{cite book | last = Lesčius | first = Vytautas | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920 | publisher = ], ] |date=2004 | location = Vilnius | pages = p.278 |

After Poland acquired control of the town and its surroundings, Lithuanian schools were closed and Polish schools were opened.<ref name="Buch_ann"/> The Poles evicted the local Lithuanian clergy, which they saw as a stronghold of Lithuanian nationalism in the region; the prominent seminary in the town was relocated.<ref name="Buch_ann"/> According to Lithuanian historian ], the repressions directed at the Lithuanian population were even more widespread, with a ban on the public use of the ], closure of various Lithuanian organizations (with 1,300 members), all Lithuanian schools<ref name="Buch_ann"/> (with approx. 300 pupils), and printing presses, confiscation of property, and burning of Lithuanian books.<ref name=LKA>{{cite book | last = Lesčius | first = Vytautas | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920 | publisher = ], ] |date=2004 | location = Vilnius | pages = p.278 |url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 9955423234 }}</ref><ref name=KA/> The ], reporting on renewed hostilities a year later, described the 1919 Sejny events as a violent occupation, in which the Lithuanian inhabitants, teachers, and religious ministers were maltreated and expelled.<ref name=nytimes>. Walter Duranty, ], ], 1920. Accessed on October 26, 2007.</ref> According to ], the uprising was a direct act of Polish government aggression against Lithuania.<ref name='Paransevicius'> Polish historian Łossowski notes that both sides mistreated civilian population and exaggerated reports to gain internal and foreign support.<ref name="Łossowski68"/> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 22:13, 28 August 2008

| Establishment of Second Polish Republic | |

|---|---|

| Greater Poland (1918-19) - Ukraine (1918-19) - Against Soviets (1919-21) - Czechoslovakia (1919) - Sejny (1919) - Upper Silesia (1919–1921) - Lithuania (1920) |

The Sejny Uprising (Template:Lang-pl) or Seinai Revolt refers to a 1919 uprising by Polish irregular forces, later aided by the regular Polish army, in the area of the town of Sejny (Lithuanian: Seinai), against Lithuanian authorities. Action began on August 23, 1919 and by September 9, 1919 Polish forces had secured the area. Control of the town changed hands several more times during the course of the following year; Sejny has remained within Poland since late 1920. The battle was part of a long-term conflict that arose in the twentieth century between Poland and Lithuania over ethnically-mixed territories in the area; the League of Nations and the Paris Peace Conference attempted to intervene in these conflicts.

The region had been occupied by Germany during World War I; after the German defeat, both Lithuanian and Polish administrative and military organizations vied for control of the town, and the uprising occurred immediately after the departure of the German occupational authorities. The town changed hands and during that time both sides used repressive measures.

The uprising damaged the plans of Polish leader Józef Piłsudski, who was planning a coup d'etat in Lithuania in order to establish a government there that would be willing to join his proposed Międzymorze federation. For that reason Piłsudski wished for the coup to be as bloodless as possible; the unplanned hostilities in Sejny further damaged Polish-Lithuanian relations, and the coup was prevented as the uprising drew the attention of Lithuanian police and intelligence forces to the activity of Polish intelligence in Lithuania.

Background

The lands surrounding the town of Suwałki had been variously part of Polish, German, and Lithuanian borderlands since the Middle Ages, and the borders in the area had shifted numerous times in the past. During the era of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the town of Sejny itself, along with the rest of the Podlaskie Voivodeship, was part of the Kingdom of Poland since 1569 rather than the Grand Duchy of Lithuania it used to belong until then. However, the town had been controlled by Dominican friars from Vilnius. During the nineteenth century the town was part of Russian-controlled Congress Poland. According to contemporary Eduard Volter's statistics in 1889 Suwałki Governorate there were 57,8% Lithuanians, 19,1% Poles, 3,5% Belarusians. Lithuanian historian Bronius Makauskas states that in the beginning of the 20th century population majority of town's and its surroundings remain Lithuanian, at lesser extend - Jews, Tatars, Poles. Polish historian Piotr Łossowski contends that the ethnic Lithuanian territories, where Lithuanians formed a majority, begun north on the town.

During World War I the region was captured by Imperial Germany, which intended to incorporate the area into its province of East Prussia. However, the German defeat in the war made those plans obsolete as it was clear that the victorious Entente powers would be willing to assign the territory to the newly-recreated states of Poland or Lithuania, rather than to defeated Germany.

This led to a conflict between Poland and Lithuania, as both sides claimed the area. The Germans, whose Ober-Ost administration of the former Suwałki Governorate was preparing to evacuate the area, initially supported the creation of a Polish administration in the area. However, as reborn Poland was becoming an ally of France, with time their support started to gradually shift towards Lithuania. Discussions of the area's future were held at the Paris Peace Conference during January 1919. On May 8, 1919, the Germans delegated the administration of the town to locally elected Lithuanian authorities, and Lithuanian partisan troops were formed by Lithunian activists in the pre-war Sejny county.

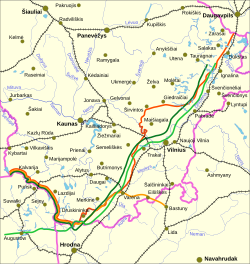

| Color | English |

|---|---|

| First, June 18 1919 | |

| Foch Line, July 27 1919 | |

| Treaty of Suwałki, October 3 1920 | |

| Final, February 3 1923 |

Since the Polish-Lithuanian talks in Paris were inconclusive, on July 18 1919,the Marshal of France, Ferdinand Foch, under the influence of Polish war mission in Paris and general Rozwadowski, presented the new, favorable to Poles, line, which became known as the Foch Line. The Lithuanian delegation was absent during the establishment of the demarcation line. The demarcation line ran from the German border in East Prussia, south of Lake Vištytis (with Wiżajny on the Polish side), north of Puńsk and then south of Lubowo. From there the line turned along the shores of Lake Galadusys, east of Bereźniki and along the Marycha and Igorka rivers to Neman. This left the southern part of the conflict area, incuding Suwałki and Sejny, in Polish hands, and the northern area in Lithuanian hands. The line roughly reflected the region's demographics, but still left significant minorities on both sides.

On July 26 the Foch Line was accepted by the Highest Council of the Entente as the provisional border between the two states. Under pressure from the Conference of Ambassadors, which would later become the League of Nations, both countries initially backed down on the issue; neither was satisfied, particularly as Polish forces were already in some areas up to 30 km over the line and showed no desire to retreat. Such repeated Polish violations of Foch line were protested in Paris. Lithuanian military forces were allowed to enter the area before the German army withdrew, which led many local Poles to believe that the Lithuanians intended to capture the entire Suvalkai region, known in Lithuanian as Suvalkija, and convince the Entente to accept this as a fait accompli. Further, the Lithuanian forces in the disputed regions (about 1,200 strong) left Suwałki by July 7, but remained in Sejny, and formed a line on the Czarna Hańcza river - Wigry Lake, in violation of the Foch Line.

On August 12 1919, a Polish meeting in Sejny attracted over 100 delegates from neighboring Polish communities; the meeting passed a resolution that "only securing the area by Polish Army can solve the problem." On 17 August, a Lithuanian counter-demonstration was staged, whose participants in turn pronounced words of a recently issued Lithuanian volunteer army recruitment proclamation: "Citizens! Our nation is in danger! To arms! We shall leave not a single occupant on our lands!" Governments of both countries were encouraging the conflict. Prime Minister of Lithuania Mykolas Sleževičius visited Sejny and in his speech called Lithuanians to defend their lands "to the end, however they can, with axes, pitchforks and scythes". In turn, the Polish government - particularly the Polish chief of state, Józef Piłsudski - was supporting the secret Polish Military Organization (PMO), which was planning a coup d'etat that would topple the sovereign government of Lithuania. The Lithuanian government was not eager to cooperate with Poland, perceiving that it would lose its sovereignty under Piłsudski's Międzymorze federation scheme. Within Lithuania, the pro-Polish faction was supported by the Lithuanian general Silvestras Žukauskas and by politician Stanisław Narutowicz. The Sejny branch of the Polish Military Organization, led by Polish regular army officers Adam Rudnicki and Wacław Zawadzki, had been preparing for the uprising since August 16; PMO irregular forces numbered about 900 PMO members and local militia volunteers.

Lithuanian historian Vytautas Lesčius has stated that the coup was meant to be accompanied by a series of PMO uprisings across all of Lithuania, scheduled for August 1919. He bases this assertion on documents stolen from a safe at PMO headquarters, located in Polish-controlled Vilnius, documenting the coordination of PMO actions in Lithuania. According to the Polish historian Tadeusz Mańczuk, Piłsudski - who both historians agree was involved in planning the coup - did not want Polish-Lithuanian hostilities, and discouraged the local PMO activists from carrying out the Sejny uprising, which would have left any new Lithuanian government less receptive to Polish federative proposals. The local PMO disregarded his recommendations and launched the uprising, which while locally successful, led to the failure of the nationwide coup. A similar argument has been presented by Polish historian Katarzyna Pisarska.

Military skirmishes

The Polish uprising, led by undercover local PMO activists commanded by Polish regular army officers, began early in the morning of August 23, 1919. The date was chosen to coincide with the withdrawal of German troops from the territory. Details of the battles differ in the accounts of Lithuanian and Polish historians.

The first Polish assault was a success, and the PMO troops took Sejny and several neighboring communities and then advanced into territories within the Lithuanian side of the Foch line. The Suwałki PMO detachment had orders to capture the entire territory of the Sejny powiat up to the city of Simnas, but growing Lithuanian resistance prevented this. On the evening of August 25 the first regular unit (41st Infantry Regiment) of the Polish army received an order to advance towards Sejny. The local Lithuanian militia and the regular army, gained an advantage over the irregular forces of PMO insurgents, and retook the city on August 26. Polish sources assert that Lithuanians there aided by a company of Germans volunteers, but Lithuanian sources assert that there are no facts supporting such findings. Lithuanian forces recovered some important documents and property, freed the Lithuanian prisoners of war taken by Poles and, according to Mańczuk, executed several of the PMO fighters they found wounded. The Lithuanian forces retreated on the same day. Lesčius, who had access to Lithuanian army documents, states the retreat was motivated by a report that a Polish cavalry unit was approaching from Suwałki. Mańczuk states that the Lithuanians had received an erroneous report that a large force of Polish regular cavalry was operating in their rear, on the Lithuanian side of the Foch line - but no such regular unit existed, and the only Polish cavalry unit in the region was an irregular PMO unit under Lieutenant Rudnicki. He agrees that the Lithuanians received a report that Polish regular troops were approaching the town. Later the next day, during the afternoon of 26 August, the PMO forces in Sejny were joined by the Polish 41st Regiment.

The last Lithuanian attempt to retake the city was made on August 28, defeated by the combined forces of the Polish army and PMO volunteers. The Polish forces forced all Lithuanian troops to retreat beyond the Foch demarcation line by September 9. The Polish regular army units did not cross the Foch line, and refused to aid the PMO insurgents still operating on the Lithuanian side; these insurgents fought in some areas for two more months.

Polish sources give total casualties for the Sejny Uprising as 37; they have no numbers for Lithuanian casualties. Based on Lithuanian army reports, Lesčius states that on the heaviest day of fighting, August 25, the casualties consisted of 45 Polish soldiers and 3 officers killed (including the Sejny commandant), and 8 Lithuanian soldiers wounded.

Aftermath

After Poland acquired control of the town and its surroundings, Lithuanian schools were closed and Polish schools were opened. The Poles evicted the local Lithuanian clergy, which they saw as a stronghold of Lithuanian nationalism in the region; the prominent seminary in the town was relocated. According to Lithuanian historian Vytautas Lesčius, the repressions directed at the Lithuanian population were even more widespread, with a ban on the public use of the Lithuanian language, closure of various Lithuanian organizations (with 1,300 members), all Lithuanian schools (with approx. 300 pupils), and printing presses, confiscation of property, and burning of Lithuanian books. The New York Times, reporting on renewed hostilities a year later, described the 1919 Sejny events as a violent occupation, in which the Lithuanian inhabitants, teachers, and religious ministers were maltreated and expelled. According to Juozas Sigitas Paransevičius, the uprising was a direct act of Polish government aggression against Lithuania.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Piłsudski wished for the coup to be as bloodless as possible, criticized those who suggested a military action, and did not plan nor wish for the Sejny uprising to occur.

The Sejny uprising doomed the Polish plan to overthrow the Lithuanian government. PMO members in Lithuania stated that the Sejny uprising had damaged their reputation, and many of its former supporters rejected calls by PMO recruiters. Lithuanian police and intelligence intensified their investigation of Polish sympathizers, and the coup, originally scheduled for 28 August 1919, was delayed until September. The plans for the coup were soon uncovered by counter-intelligence, and Lithuanian Army officers moved to prevent it. The first arrests in the case were made on August 27 and continued until the end of September. During the investigations lists of PMO supporters were found, and the organisation was completely eliminated in Lithuania.

A year later, the town was captured by Soviet Russia during the course of the Polish-Soviet War. On July 12, 1920 a Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920 was signed, granting Lithuania the right to control the Sejny area in exchange for the right of passage for Soviet forces through Lithuanian territory. As a matter of fact the terriotry was contolled by the Soviets already. On July 19, 1920, the Lithuanians attacked the Polish defenders and recaptured the town. The Lithuanian authorities were once again established in the area. After the Battle of Warsaw in 1920, the Soviet forces were defeated, and the Polish Army again entered the Sejny area. The Lithuanian authorities persisted in their claim, and the town was an object of contention during the Polish-Lithuanian War. As the town was located only some 2 kilometres from the Lithuanian border, it was easily captured by Lithuanian forces. The assault was repelled and the Polish Army recaptured the town on September 9. On September 10, the last of the Lithuanian units retreated to the other side of the border, and on October 7 a cease fire agreement was signed, leaving Sejny on the Polish side of the border.

Notes and references

- ^ Template:Pl icon Powstanie Sejneńskie 1919 on the pages of Association "Polish Community"

- ^ Template:Pl icon Historia, official pages of Sejny town

- Šenavičienė, Ieva (1999). "Tautos budimas ir blaivybės sąjūdis". Istorija. 40: p.3.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Makauskas, Bronius (1999). "Pietinės Sūduvos lietuviai už šiaudinės administracinės linijos ir geležinės sienos (1920–1991 m.)". Voruta, No.27-30. ISSN 1392-0677.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 8305127699, p.51

- ^ Template:Pl icon Stanisław Buchowski. "Powstanie Sejneńskie 23-28 sierpnia 1919 roku (Sejny uprising of [[August 23]]-[[August 28]] [[1919]])". www.g1.powiat.sejny.pl. Gimnazjum Nr. 1 w Sejnach. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Tadeusz Mańczuk (2001). "Z Orłem przeciw Pogoni. Powstanie sejneńskie 1919". Mówią Wieki. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Katarzyna Pisarska, Stosunki Polsko - Litewskie w latach 1926-1927

- ^ Lesčius, Vytautas (2003). Karo archyvas XVIII, chapter Lietuvos ir Lenkijos krainis konfliktas del Seinu krasto 1919 metais (PDF). Vilnius: Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. pp.188-189. ISSN 1392-6489.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Krzysztof Buchowski, Polish-Lithanian Relations in Seinai Region at the Turn of the nineteenth and twentieth Centuries. LCAS Annuals, vol. XXIII

- Makauskas, Bronius (1999).Foch had been influenced by Polish war mission in Paris delivered favorable to Poles new administration line on July 26. //Foch under the influenced of general Rozwadowski question solved as technical rather than ethnic.

- ^ Poles Attacked By Lithuanians. Walter Duranty, New York Times, September 6, 1920. Accessed on October 26, 2007.

- ^ Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 8305127699, p.67

- ^ Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920. Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. p.259-278. SBN 9955423234.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|sbn=value: length (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Paransevičius, Juozas Sigitas. " "Seinai – 1918-1920 metai" (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Makauskas, Bronius (1999). "Pietinės Sūduvos lietuviai už šiaudinės administracinės linijos ir geležinės sienos (1920–1991 m.)". Voruta, No.27-30. ISSN 1392-0677.

German participation among Lithuanian side is mentioned by Polish sources, but these claims are not supported by facts.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920. Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. p.278. ISBN 9955423234.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 8305127699, p.66

| Polish uprisings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Poland |  | ||||

| Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| ||||

| After the partitions | |||||

| Second Republic | |||||

| World War II |

| ||||

| Polish wars and conflicts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General and related |

| ||||||||

| Piast Poland |

| ||||||||

| Jagiellon Poland |

| ||||||||

| Commonwealth |

| ||||||||

| Poland partitioned | |||||||||

| Second Republic | |||||||||

| World War II in Poland |

| ||||||||

| People's Republic | |||||||||

| Third Republic | |||||||||