| Revision as of 16:50, 11 November 2005 editAntandrus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators111,288 editsm Reverted edits by 217.73.101.30 to last version by Bogdangiusca← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:42, 11 November 2005 edit undo217.73.101.30 (talk) →Caucasian originNext edit → | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

| Zacharie Mayani is not the only person that has linked Pelasgian with Albanian. Aristides P. Kollias in his books writes that the Pelasgian race is the progenitor race of Greeks and Latins, and Albanians are the only ones that preserved the words as studies from Vlora Falaschi, Giuseppe Catapano, Stanislao Marchiano, Jean Cloude Faverial, Robert D'Angely, Aristides P. Kolias, Eqrem Cabej claim. Recently another French scholar, Mathieu Aref, has put forth the claim that "the earliest Greeks" were what he terms "Pelasgo-Albanians". | Zacharie Mayani is not the only person that has linked Pelasgian with Albanian. Aristides P. Kollias in his books writes that the Pelasgian race is the progenitor race of Greeks and Latins, and Albanians are the only ones that preserved the words as studies from Vlora Falaschi, Giuseppe Catapano, Stanislao Marchiano, Jean Cloude Faverial, Robert D'Angely, Aristides P. Kolias, Eqrem Cabej claim. Recently another French scholar, Mathieu Aref, has put forth the claim that "the earliest Greeks" were what he terms "Pelasgo-Albanians". | ||

| ===Caucasian origin=== | |||

| ] | |||

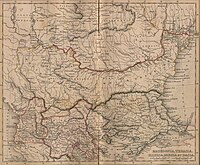

| The Caucasian theory was first expounded by ] ]s (such as ]) who were familiar with the works of the classical geographers and historians; it was developed in the 1820s by the French diplomat and influential writer on the Balkans, François Pouqueville; and in ] it was presented in a polemical response to the work of Johann Georg von Hahn by a Greek doctoral student at Göttingen, Nikolaos Nikokles. By the late ] this theory was in retreat, as the work of linguists demonstrated that Albanian was definitely Indo-European, not Caucasian. | |||

| The Caucasian theory is now still promoted by certain ]n, ], or ] nationalists, even though the scientific community overall rejects it. None of the arguments for it have been deemed strong or convincing by the general scholarly community. | |||

| The Caucasian theory is based on the fact that there was ancient country in the Caucasus region named Albania (See: ]). The inhabitants of this country were named Albanians, and there was also city named Albanopolis (present day ]) in Caucasian Albania (the city with the same name was mentioned in Illyria). However, if Albanians did come from Caucasus, it must happen very early. Some historians suggest that this Albanian migration from the Caucasus might have occured in the ] BC, after the ]. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 20:42, 11 November 2005

The origin of Albanians has been for some time a matter of dispute among historians. Albanians are people who speak Albanian, an Indo-European language that has no other close living relative, making it difficult to determine from what ancient Balkan language it evolved.

Place of origin

The place where Albanian was formed is also disputed, but by studying the language we can learn that Albanian was formed in a mountainous region rather than plain or seacoast: while the words for plants and animals that are characteristic of the mountainous regions are entirely original, the names for sea-fishes and those for agricultural activities (such as ploughing) are borrowed from other languages.

We can also be sure that the Albanians didn't live in Dalmatia, because the Latin influence over Albanian is of Balkan Romance (that evolved into Romanian) origin rather than of Dalmatian origin. This Balkan Romance influence includes Latin words exhibiting idiomatic expressions and meaning changes that are only found in Romanian and not in other Romance languages. Adding this to the words common only to Albanian and Romanian, we can assume that the Romanians and Albanians once lived closely. Generally the areas where this might have happened are considered to be regions varying from Transylvania, Eastern Serbia (region around Naissus/Nis), Kosovo and Northern Albania/Macedonia.

However, Romanian has most agricultural terms of Latin origin, but not terms related to city activities, showing that Romanians, as opposed to Albanians (who were originally shepherds), were agricultural people in the low-plains.

Some scholars even explain the gap between Bulgarian and Serbian languages by an Albanian-Romanian buffer-zone east of the Morava river. Although an intermediary Serbian dialect exists, it was formed only later after the Serbian expansion to the east.

Another argument that sustains a northern origin of Albanians is the relative small number of words of Greek origin, although Southern Illyria was under the influence of Greek/Byzantine civilization and language, especially after the break-down of the Roman Empire.

Earliest mentions of Albanians in Albania

- In the second century BC, in the History of the World written by Polybius, there is mention of a city named Arbon in present day central Albania. The people who lived there were called Arbanios and Arbanitai.

- In the first century AD, Pliny mentions an Illyrian tribe named Olbonenses.

- In the second century AD, Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria, drafted a map of remarkable significance for the history of Illyria. This map shows the city of Albanopolis (located south of Durrës). Ptolemy also mentions the Illyrian tribe named Albanoi, who lived around this city.

- After centuries of silence, there is mention of the ancestors of the modern Albanians in the form of Arbanitai of Arbanon in Anna Comnenas account of the troubles in that region caused in the reign of her father Alexius I Comnenus (1081- 1118) by the Normans. (The Alexiad, 4)

- In History written in 1079-1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates was refer to the "Albanoi" as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium.

- 1285 in Dubrovnik (Ragusa) where a sizeable Albanian community had existed for some time. In the investigation of a robbery in the house of Petro del Volcio of Belena (now Prati), a certain Matthew, son of Mark of Mançe, who appears to have been witness to the crime, states: "Audivi unam vocem clamantem in monte in lingua albanesca" (I heard a voice crying in the mountains in the Albanian language).

Ethnic origin

The two chief candidates considered by historians are Illyrian or Thracian, though there were other groups in the ancient Balkans that were neither Illyrian nor Thracian, including Paionians (who lived north of Macedon) and Agrianes. The Illyrian language and the Thracian language are generally considered to have been on different Indo-European branches. Not much is left of the old Illyrian or Thracian tongues, making it difficult to match Albanian with any of them.

There is debate whether the Illyrian language was Centum or Satem, and there is no conclusive evidence yet either way, though what evidence there is strongly indicates that Illyrian was centum. It is also uncertain whether the Illyrians spoke a homogenous language or rather a collection of dialects or even different languages that were wrongly considered the same language by ancient writers. The same is sometimes said of the Thracian language. For example, based on the toponyms, it has been argued that Thracian and Dacian may be different languages or dialects.

In the early half of the 20th century, many scholars thought that Thracian and Illyrian were one language, but due to the lack of evidence, most linguists are skeptical and now reject this idea, and usually place them on different branches. The Messapian language is often considered to have been an Illyrian language, but this is disputed by some.

Illyrian Origin

The theory is that the Albanian language represents a survival of an indigenous Illyrian language. There is a gap of several centuries between the last historical mention of the Illyrians (and the Illyrian tribe Albanoi) and the later mention of Albanians and of the names Albanon and Arbanon to indicate the region. Supporters of the theory say that the term Albanian gradually came to be applied to the surviving Illyrians.

Arguments for:

- there are some direct correspondances of vocabulary between Albanian and Illyrian.

- several Albanian scholars maintain that the Komani-Kruja burial sites support the Illyrian-Albanian continuity theory (but other scholars of Slavic origin reject this and consider that the remains indicate a population of Romanized Illyrians who spoke a Romanic language)

- there are no records that indicate a migration of Albanians into present day Albania

- Some Illyrian names among Albanians are used, yet it is known that many of the names were only lately and consciously introduced to emphasize the Illyrian ancestry that is claimed.

- According to Dr. S. S. Juka, "Kosova’s toponomy is another indication that the ancestors of the Albanians must have inhabited Dardania."

- Albanoi tribe is mentioned as an Illyrian tribe by the ancient geographer Ptolemy in Book 3 of ‘Geographia’ around the same area where Albania is in today.

- Ancient Illyrian terms for cities, rivers and mountains are found to this day in the Albanian language. However, scholars have pointed out that many of these terms appear to have entered Albanian through an intermediary, not directly.

- When describing an Albanian revolt against the Byzantine Empire, Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus states "All the swarm of Illyrians" when describing the Albanians in one of his letters.

Arguments against:

- the modern Albanians were not mentioned in Byzantine chronicles until 1043, although Illyria was part of the Byzantine Empire, and since the Illyrians are referred to for the last time as an ethnic group in Miracula Sancti Demetri (7th century AD.), some scholars maintain that after the arrival of the Slavs the Illyrians were extinct.

- (see the Jireček Line) it is believed that most inhabitants of Illyria were Hellenized (the Southern part) and later Romanized (opponents say that some Illyrians were not Hellenized or Romanized, but maintained their own language, which may have been a proto-Albanian language).

- most Illyrian toponyms, hydronyms, names, and words have not been shown to be related to Albanian, and they do not indicate that Illyrians spoke a proto-Albanian language (opponents say that many of these toponyms, hydronyms and names are Hellenized and Romanized; whether the change in form is dramatic or not is hard to know in a number of cases).

- ancient Illyrian toponyms (such as Shkoder from the ancient Scodra, Tomor from ancient Tomarus) were not directly inherited in Albanian, as their modern names do not correspond to the phonetic laws of Albanian

- a number of scholars believe that Illyrian was a Centum language, though others disagree. If Illyrian was Centum, then it is unlikely that Albanian (which is Satem) is an Illyrian language

Thracian/Dacian origin

Arguments for:

- Albanian shares several hundred common words with Romanian, believed to be part of the Dacian substrate (see: List of Dacian words), as well as grammatical features (see Balkan language union) and phonological (such as the common phonemes or the rhotacism of "n").

- Vladimir Georgiev demonstrated that the phonetics of the Dacian language (based largely on his interpretation of the toponyms) may have been close to those of Albanian.

- names of the cities that follow Albanian phonetic laws (which include Shtip, Shkupi and Nish) are in the areas once inhabited by Thracians, Dardani, and Paionians.

- There are some correspondences between Thracian and Albanian words, but few in comparison to the body of material.

Arguments against:

- many Dacians and Thracian placenames were made out of joined names (such as "Sucidava" or "Bessapara"), while Albanian language does not allow this.

- there are no records that indicate a migration of Dacians into present day Albania.

- from the extensive body of Thracian and Dacian words, names, and language-elements, some have been linked to Albanian; the majority of Daco-Thracian words and names may not have Albanian correspondances.

- the common non-Romance words between Albanian and Romanian may possibly be explained by another scenario, and some of these common words may have been words that were exchanged between proto-Albanians and Dacians and Thracians in ancient times, the exchange going both ways, however, this would not explain the common Romance words and expressions.

- the closeness in phonetics between Dacian and Albanian that Vladimir Georgiev and others suggest is not accepted by all linguists; it has been challenged and is based on incomplete evidence.

- the Balkan language union may date back to Neolithic times according to Mario Alinei, so what phonetic similarities may have existed between Dacian and Albanian could be explained by linguistic interactions over the centuries.

Pelasgian/Etruscan origin

The Pelasgians are generally considered to be the people that were living in the Balkans before the Indo-European arrival, the Greek writers mentioning them as autochthonic peoples that predated Hellenic settlement. Though generally considered pre-Indo-European, Vladimir Georgiev and some other scholars have sought to include Pelasgian as an Indo-European language.

The Etruscans were also indigenous people of Europe, but it is not known whether they were or not related to the Pelasgians. An inscription found on a stele in Lemnos shows that a non-Indo-European language related to Etruscan (see Lemnian language) was once spoken in the Aegean.

The French author Zacharie Mayani put forth a thesis that the Etruscan language had links to the Albanian language. The Albanian régime of Enver Hoxha embraced this theory for propaganda reasons, and extended it to include the Pelasgians in this association. Mainstream scholars have paid Mayani's arguments little serious attention.

Zacharie Mayani is not the only person that has linked Pelasgian with Albanian. Aristides P. Kollias in his books writes that the Pelasgian race is the progenitor race of Greeks and Latins, and Albanians are the only ones that preserved the words as studies from Vlora Falaschi, Giuseppe Catapano, Stanislao Marchiano, Jean Cloude Faverial, Robert D'Angely, Aristides P. Kolias, Eqrem Cabej claim. Recently another French scholar, Mathieu Aref, has put forth the claim that "the earliest Greeks" were what he terms "Pelasgo-Albanians".

See also

- History of Albania

- Paleo-Balkan languages

- Illyrian language

- Dacian language

- Thracian language

- Origin of Romanians

References

- Duridanov, Ivan. "The Language of the Thracians", (Ezikyt na trakite), Nauka i izkustvo, Sofia, 1976

- Georgiev, Vladimir. "Genesis of the Balkan People", The Slavonic and East European Review 44, no. 103, 1960, p. 285-297

- Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history", Macmilan, London, 1998, p. 22-40

- Eric P. Hamp, University of Chigaco The Position of Albanian (Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25-27, 1963, ed. By Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel)

- Rosetti, Alexandru. "History of the Romanian language" (Istoria limbii române), 2 vols., Bucharest, 1965-1969.

- Alinei, Mario. "Balkan sprachbund may date back to Neolithic times", May 2003.

- Wilkes, John. "The Illyrians", Oxford, 1992.

- Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (Geschichte der Serben), Gotha, 1911

- Cabej, Eqrem "Die aelteren Wohnsitze der Albaner auf der Balkanhalbinsel im Lichte der Sprache und Ortsnamen", Florence, 1961

- G. Weigand, "Sind die Albaner die Nachkommen der Illyrier oder der Thraker"

- By Dr. S.S. Juka Kosova: The Albanians in Yugoslavia in light of historical documents

- Michael Attaliota: Historia, Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. Impensis ed. NJeberi, Bonnae

- "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective"

- Kladas Uprising, constains translated letter of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus

- Hasdeu, Bogdan Petriceicu "Cine sunt albanesiǐ?", Academia Română, 1901.