| Revision as of 11:34, 14 November 2005 editCTSWyneken (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,997 edits Some reorganization, transition work← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:44, 14 November 2005 edit undoCTSWyneken (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,997 edits commented out material to edit down to fit our articleNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| The relationship between Luther and the Jewish people is the subject of much controversy. ''']''' has been accused of ''']''', primarily in relation to his work '']''. | The relationship between Luther and the Jewish people is the subject of much controversy. ''']''' has been accused of ''']''', primarily in relation to his work '']''. | ||

| <!-- | |||

| Luther was at one time or another during his life hostile towards just about everybody, including his own parishioners, good friends, allies, opponents and, himself. Like most geniuses, he often found it impossible to understand why others could not comprehend what was, to him, obvious. His most obvious flaw was his temper. He often berated himself for this, even in print. | |||

| Luther did not live in the 20th Century, where we have learned to deal gently with each other in public. It was simply part of the times in which he lived that one did not mince words. He was more abusive toward the papists and the "Sacramentarians" (Reformed) for a longer period of his life than he ever was toward the Jews, and these were fellow Christians. To this list we can readily add the following: the Turks (Muslims), the rulers, the peasants, and many others. While we should not excuse or emulate the extreme nature of Luther's polemical language, it was part of the age in which he lived. | |||

| The Church and the State were closely connected in Luther's day. There was a certain amount of toleration of unbelievers of whatever conviction as long as they were quiet about it. But to publicly teach heresy or deny and insult the Christian faith was not tolerated. Doing so could get one exiled, imprisoned, or worse. Luther himself was never more than 50 miles away from death by burning at the stake for his views. In Calvinist Geneva a notorious anti-Trinitarian was publicly executed, although the Lutherans never went that far (except in the case of one radical Schwaermer , but in this case the charge against him was disturbing the peace and leading a revolt against the government, not false doctrine as such, although the reason he had done those things was because of religious conviction). The Jews who frustrated Luther later in his life were openly criticizing the distinctive doctrines of Christianity, and Luther was simply advising (albeit in intemperate language) that the laws against public blasphemy be carried out. | |||

| One must keep in mind that Luther's whole approach was religious. Luther was anti-Judaic, not anti-Semitic. He opposed Judaism as, from his perspective, a false religion, which carries its followers off to hell. He did not oppose Jews and heretics as persons--Luther is known, for example, for intervening with authorities to protect individual Jews and, in at least one case, putting up his personal Christian opponent, a former friend and a theological enemy, to protect that man from the authorities. | |||

| So, what do we make of it all? First, we need to be fair and credit Luther for the good things he did and said about the Jews. We also should abhor the intemperate language and his cruel approach to opponents. All of this needs to be set against the background of the time and place in which Luther lived. However, it is grossly unfair to Luther to call him anti-Semitic. | |||

| --> | |||

| == Luther's Statements about the Jews == | == Luther's Statements about the Jews == | ||

Revision as of 11:44, 14 November 2005

The relationship between Luther and the Jewish people is the subject of much controversy. Martin Luther has been accused of Anti-Semitism, primarily in relation to his work On the Jews and their Lies.

Luther's Statements about the Jews

Luther's first known comment on the Jewish people is in a letter written to George Spalatin in 1514 he stated:

I have come to the conclusion that the Jews will always curse and blaspheme God and his King Christ, as all the prophets have predicted....For they are thus given over by the wrath of God to reprobation, that they may become incorrigible, as Ecclesiastes says, for every one who is incorrigible is rendered worse rather than better by correction.

Seven years later Luther distinguished between the religious and racial aspects of the Jews in his 1523 essay That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, telling his followers that

"When we are inclined to boast of our position we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ. We are aliens and in-laws; they are blood relatives, cousins, and brothers of our Lord. Therefore, if one is to boast of flesh and blood the Jews are actually nearer to Christ than we are."

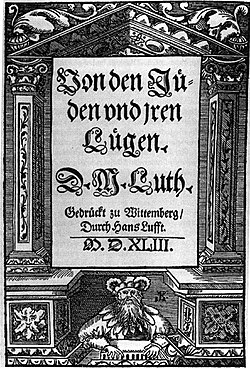

Twenty years later, after his overtures to Jews failed to convince Jewish people to adopt Christianity, he wrote On the Jews and Their Lies, a work which has been described as "a notorious Antisemitic document"), and which, according to Paul Johnson, "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust." (A History of the Jews, 1987, p.242)

In the book Luther views the Jews' lineage in quite a different light. He states "There is one thing about which they boast and pride themselves beyond measure, and that is their descent from the foremost people on earth, from Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, and from the twelve patriarchs, and thus from the holy people of Israel." He quotes the words of Jesus in Matthew 12:34, where Jesus called the Jewish religious leaders (Pharisees) of his day "a brood of vipers and children of the devil", and attributes this characteristic to all Jews. In the book, written three years before his death, he describes the Jews as (among other things) "miserable, blind, and senseless", "truly stupid fools", "thieves and robbers", "lazy rogues", "daily murderers", and "vermin", likens them to "gangrene", and recommends that Jewish synagogues and schools be burned, their homes destroyed, their writings be confiscated, their rabbis be forbidden to teach, their travel be restricted, that lending money be outlawed for them and that they be forced to earn their wages in farming. Finally, Luther advised "f we wish to wash our hands of the Jews' blasphemy and not share in their guilt, we have to part company with them. They must be driven from our country" and "we must drive them out like mad dogs."

Several months after publishing On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther wrote another attack on Jews titled Schem Hamephoras, in which he explicitly equated Jews with the Devil.

In his final sermon shortly before his death, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord" (Weimar ed., vol. 51, p. 195).

Controversy over Luther's view of the Jews

Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian anti-Semitism, and a reflection of earlier anti-Semitic expulsions in the 14th century, when Jews from other countries like France and Spain were invited into Germany. When Luther writes that the Jews should be expelled from his homeland, he expresses widespread feelings of his times, and these sentiments were echoed in the Germany of the 1930s. According to Daniel Goldhagen

One leading Protestant churchman, Bishop Martin Sasse published a compendium of Martin Luther's antisemitic vitriol shortly after Kristallnacht's orgy of anti-Jewish violence. In the foreword to the volume, he applauded the burning of the synagogues and the coincidence of the day: On November 10, 1938, on Luther's birthday, the synagogues are burning in Germany. The German people, he urged, ought to heed these words of the greatest antisemite of his time, the warner of his people against the Jews.

Roland Bainton, noted church historian and Luther biographer, wrote with reference to On the Jews and Their Lies: "One could wish that Luther had died before ever this tract was written. His position was entirely religious and in no respect racial" (Here I Stand, , p. 297). This is later echoed by James M. Kittelson writing about Luther's correspondence with Jewish scholar Josel Rosheim, (Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Carreer , p. 274): "There was no anti-Semitism in this response. Moreover, Luther never became an anti-Semite in the modern, racial sense of the term." This might be construed to support the view that Luther's ideas in On the Jews and Their Lies were anti-Judaic rather than anti-Semitic in that they were not motivated by a racial or ethnic prejudice. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America statement cited below makes this distinction on the basis of chronology, that Anti-Judaism is the prototype of Anti-Semitism. In the view of just people there is always the danger of mitigating Anti-Semitism however it manifests itself.

In 1983, the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, noting that "Anti-Semitism and other forms of racism are a continuing problem in our world," made an official statement disassociating themselves from what they describe as "intemperate remarks about Jews" in Luther's works.

In 1988 Lutheran theologian Stephen Westerholm argued that Luther's attack on Judaism was part and parcel of his attack on the Catholic Church — that Luther was applying a Pauline critique of Phariseism as legalistic and hypocritical to the Catholic Church. Westerholm rejects Luther's interpretation of Judaism and his apparent anti-Semitism, and acknowledges that Paul's critique of the Pharisees is based on a charicature that lacks historical merit. But Westermark points out that whatever problems exist in Paul's and Luther's arguments against Jews, what Paul, and later, Luther, were arguing for was and continues to be an important vision of Christianity.

In 1994, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America publicly rejected what it described as "Luther's anti-Judaic diatribes and the violent recommendations of his later writings against the Jews," and their "appropriation... by modern anti-Semites for the teaching of hatred toward Judaism or toward the Jewish people in our day."

External links

- Antisemitism - Reformation from the Florida Holocaust Museum.