| Revision as of 21:38, 6 May 2009 editPer Honor et Gloria (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers53,031 edits rfs← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:17, 7 May 2009 edit undoMarek69 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers195,899 edits clean up, typos fixed: campaings → campaigns using AWBNext edit → | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| Contacts started soon after the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate and the concommital fall of the ] in 751. The Carolingian ruler ] had a powerful enough position in ] to "make his alliance valuable to the Abbasid ] of ], ]".<ref>Deanesly, p.294 </ref> Remants of the Umayyad Caliphate were established firmly in southern Spain under ], and constituted a strategic threat both to the Carolingian on their southern border, and to the Abbasid at the Western end of their dominion. | Contacts started soon after the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate and the concommital fall of the ] in 751. The Carolingian ruler ] had a powerful enough position in ] to "make his alliance valuable to the Abbasid ] of ], ]".<ref>Deanesly, p.294 </ref> Remants of the Umayyad Caliphate were established firmly in southern Spain under ], and constituted a strategic threat both to the Carolingian on their southern border, and to the Abbasid at the Western end of their dominion. | ||

| ] or gold ] of the English king ] (757–796), a copy of the dinars of the ] (774). It combines the Latin legend OFFA REX with Arabic legends. ].]] | ] or gold ] of the English king ] (757–796), a copy of the dinars of the ] (774). It combines the Latin legend OFFA REX with Arabic legends. ].]] | ||

| Embassies were exchanged both ways, with the apparent objective of cooperating against the Umayyads of ]: a Frank embassy went to ] in 765, and an Abbasid embassy visited France in 768.<ref>Deanesly, p.294 </ref> | Embassies were exchanged both ways, with the apparent objective of cooperating against the Umayyads of ]: a Frank embassy went to ] in 765, and an Abbasid embassy visited France in 768.<ref>Deanesly, p.294 </ref> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| ==Further exchanges== | ==Further exchanges== | ||

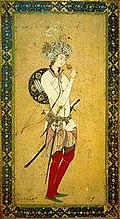

| {{multiple image| align = right | direction = horizontal | header = | header_align = left/right/center | footer = ] and ] exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.<br>'''Left image''': A coin of ] with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (''Karolus imperator augustus'').<br> '''Right image''': Persian miniature representing Harun Al-Rashid.| footer_align = left | image1 =Charlemagne denier Mayence 812 814.jpg| width1 = 227 | caption1 = | image2 =Harun Al-Rashid and the World of the Thousand and One Nights.jpg| width2 = 120 | caption2 = }} | {{multiple image| align = right | direction = horizontal | header = | header_align = left/right/center | footer = ] and ] exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.<br>'''Left image''': A coin of ] with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (''Karolus imperator augustus'').<br> '''Right image''': Persian miniature representing Harun Al-Rashid.| footer_align = left | image1 =Charlemagne denier Mayence 812 814.jpg| width1 = 227 | caption1 = | image2 =Harun Al-Rashid and the World of the Thousand and One Nights.jpg| width2 = 120 | caption2 = }} | ||

| After these |

After these campaigns, there were again numerous embassies between ] and the Abbasid caliph ] from 797,<ref>Heck, p. 172 </ref> apparently in view of a Carolingian-Abbasid alliance against ],<ref>Heck, p. 172</ref> or with a view to gaining an alliance against the Umayyads of Spain.<ref>O'Callaghan, p.106</ref> Indeed, "it is likely that the Carolingians tried to seek an alliance with the Abbasids in order to weaken the power of their enemies at the time: the Byzantine empire and the Umayyads of Spain",<ref>''The oliphant'' Avinoam Shalem p.94-95 </ref> and that they were "forming a pact against a common enemy - namely the Muslim rulers in Umayyad Spain".<ref>''Beyond the Arab disease'' by Riad Nourallah p.51 </ref> | ||

| Apparently led by encouragements from Spain, ], king of ], captured ] in 801, but failed to extend his conquests to ], which would remain Muslim for the next 300 years.<ref>O'Callaghan, p.106</ref> | Apparently led by encouragements from Spain, ], king of ], captured ] in 801, but failed to extend his conquests to ], which would remain Muslim for the next 300 years.<ref>O'Callaghan, p.106</ref> | ||

Revision as of 01:17, 7 May 2009

An Abbasid-Carolingian alliance was attempted and partially formed during the 8th to 9th century through a series of embassies, rapprochements and combined military operations between the Frankish Carolingian Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate or the pro-Abbasid Muslim rulers in Spain. These contacts followed the intense conflict between the Carolingians and the Umayyads, marked by the landslide Battle of Tours in 732, and were aimed at establishing a counter-alliance with the faraway Abbasid Empire. Slightly later, another Carolingian-Abbasid alliance was attempted in a conflict against Byzantium.

Contacts under Pepin (765-768)

Contacts started soon after the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate and the concommital fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 751. The Carolingian ruler Pepin the Short had a powerful enough position in Europe to "make his alliance valuable to the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, al-Mansur". Remants of the Umayyad Caliphate were established firmly in southern Spain under Abd ar-Rahman I, and constituted a strategic threat both to the Carolingian on their southern border, and to the Abbasid at the Western end of their dominion.

Embassies were exchanged both ways, with the apparent objective of cooperating against the Umayyads of Spain: a Frank embassy went to Baghdad in 765, and an Abbasid embassy visited France in 768.

Commercial exchanges occurred between the Carolingian and Abassid realms, and Arabic coins are known to have spread in Carolingian Europe in that period. As a famous example, the 8th century English king Offa of Mercia is known to have minted copies of Abbasid dinars struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur with "Offa Rex" centered on the reverse.

Military alliance in Spain (777-778)

In 777, pro-Abbasid rulers of northern Spain contacted the Carolingian to request help against the powerful Ummayyad Caliphate in southern Spain, still led by Abd ar-Rahman I. Sulayman al-Arabi the pro-Abbasid Wali (governor) of Barcelona and Girona sent a delegation to Charlemagne in Paderborn, offering his submission, together with the allegiance of Husayn of Zaragoza and Abu Taur of Huesca in return for military aid. The three Umayyad ruler also conveyed that the caliph of Baghdad, Muhammad al-Mahdi, was preparing an invasion force against Abd al-Rhaman I.

Following the sealing of this alliance at Paderborn, Charlemagne marched across the Pyrenees in 778 "at the head of all the forces he could muster". His troops were welcomed in Barcelona and Girona by Sulayman al-Arabi. As he moved towards Zaragoza, the troops of Charlemagne were joined by troops led by Sulayman. Husayn of Zaragoza, however, refused to surrender the city, claiming that he had never promised Charlemagne his allegiance. Meanwhile, the force sent by the Baghdad caliphate seems to have been stopped near Barcelona. After a month of siege at Zaragoza, Charlemagne decided to return to his kingdom. On his retreat, Charlemagne suffered an attack from the Basques in central Navarra. As a reprisal he attacked Pamplona, destroying it. However on his retreat north his baggage train was ambushed by the Basques at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass August 15, 778.

Carolingian presence remained south of the Pyrenees however, and the city of Girona was captured in 785, and they then concentrated on expanding their rule to Vich, Caserras and Cardona.

The Muslims made their last incursion in Gaul in 793, where they sacked the suburbs of Narbonne, and defeated Count William of Toulouse near Carcassonne.

Further exchanges

Charlemagne and Harun Al-Rashid exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.

Charlemagne and Harun Al-Rashid exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.Left image: A coin of Charlemagne with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (Karolus imperator augustus).

Right image: Persian miniature representing Harun Al-Rashid.

After these campaigns, there were again numerous embassies between Charlemagne and the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid from 797, apparently in view of a Carolingian-Abbasid alliance against Byzantium, or with a view to gaining an alliance against the Umayyads of Spain. Indeed, "it is likely that the Carolingians tried to seek an alliance with the Abbasids in order to weaken the power of their enemies at the time: the Byzantine empire and the Umayyads of Spain", and that they were "forming a pact against a common enemy - namely the Muslim rulers in Umayyad Spain".

Apparently led by encouragements from Spain, Louis the Pious, king of Aquitaine, captured Barcelona in 801, but failed to extend his conquests to Tortosa, which would remain Muslim for the next 300 years.

Three embassies were sent by Charlemagne to Harun al-Rashid's court and the latter sent at least two embassies to the Charlemagne. Harun al-Rashid is reported to have sent numerous presents to Charlemagne, such as aromatics, fabrics, a clock, a chessboard, and an elephant named Abu 'Abbas. Harun al-Rashid is also reported to have offered the custody of the Holy places in Jerusalem to Charlemagne.

The third and final embassy was sent by Charlemagne in 809, but it arrived after Harun al'Rashid had died. It seems that in 831, his son al Ma'mun also sent an embassy to Louis the Pious. These embassies also seems to have had the objective of promoting commerce between the two realms.

After 814 and the accession of Louis the Pious to the throne, interal dissensions prevented the Carolingians from further ventures into Spain.

Almost a century later Queen Bertha of Rome is reported to have sent an embassy to the Abbasid caliph Al-Muktafi, requesting friendship and a marital alliance.

Notes

- Heck, p.172

- Shalem, p.94-95

- O'Callaghan p.106

- Deanesly, p.294

- Deanesly, p.294

- Goody, p.80

- British Museum

- Medieval European Coinage By Philip Grierson p.330

- Lewis, p.244

- Lewis, p.244

- Lewis, p.244

- Lewis, p.245

- Lewis, p.246

- Lewis, p.253

- Lewis, p.246

- Lewis, p.249

- Lewis, p.249

- Lewis, p.249

- Lewis, p.251-267

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- Heck, p. 172

- Heck, p. 172

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- The oliphant Avinoam Shalem p.94-95

- Beyond the Arab disease by Riad Nourallah p.51

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- Heck, p. 172

- Heck, p. 172

- Heck, p. 172

- Heck, p. 172

- Heck, p. 173

- Heck, p. 173

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- Heck, p. 173

References

- Margaret Deanesly A History of Early Medieval Europe Taylor & Francis, London Methuen & Co, Ltd

- David Levering Lewis God's Crucible Islam and the Making of Europe, 570-1215 W.W. Norton, 2008 ISBN 9780393064728

- Gene W. Heck When worlds collide: exploring the ideological and political foundations of the clash of civilizations Rowman & Littlefield, 2007 ISBN 0742558568

- Jack Goody Islam in Europe, Polity Press, 2004, ISBN 9780745631936

- Joseph F. O'Callaghan A History of Medieval Spain Cornell University Press, 1983 ISBN 0801492645