| Revision as of 22:29, 16 July 2009 editBeno1000 (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers3,659 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:04, 27 July 2009 edit undoSeb az86556 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers40,390 edits merge-proposalNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{merge|Zululand|Talk:THIS PAGE#Merger proposal|date=July 2009}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | {{Infobox Former Country | ||

| |native_name=''Wene wa Zulu'' | |native_name=''Wene wa Zulu'' | ||

Revision as of 21:04, 27 July 2009

| It has been suggested that this article be merged with Zululand and Talk:THIS PAGE#Merger proposal. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2009. |

| Kingdom of ZuluWene wa Zulu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1816–1880 | |||||||||

| Capital | KwaBulawayo; later Ulundi | ||||||||

| Other languages | isiZulu | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| • 1816-1828 | Shaka kaSenzangakhona (first) | ||||||||

| • 1872-1880 | Cetshwayo kaMpande (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| • Zulu take over Mtetwa Paramountcy under Shaka | 1816 | ||||||||

| • Dissolution by Cape Colony | 1880 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

| • 1828 | 250,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Cattle | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire, was a Southern African state in what is now South Africa. The small kingdom grew to dominate much of Southern Africa. It came into conflict with the British empire in the 1870s (see Anglo-Zulu War) and was defeated, despite early Zulu victories in the war. The land which formerly comprised the Zulu Kingdom is now the province of KwaZulu Natal in South Africa. The Zulu ethnic group (sometimes also referred to as the Zulu tribe) are now the most numerous ethnic group in South Africa, and the Zulu language is the second most widely spoken language in South Africa after English, and Zulu cultural traditions are still very much alive in the country.

The rise of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka

Main article: Shaka

Shaka Zulu was the illegitimate son of Senzangakona, chief of the Zulus. He was born circa 1787. He and his mother, Nandi, were exiled by Senzangakona, and found refuge with the Mthethwa. Shaka fought as a warrior under Dingiswayo, leader of the Mtetwa Paramountcy. When Senzangakona died, Dingiswayo helped Shaka claim his place as chief of the Zulu Kingdom.

The bloody ascendancy of Dingane

Shaka was succeeded by Dingane, his half brother, who conspired with Mhlangano, another half-brother, to murder him. Following this assassination, Dingane murdered Mhlangano, and took over the throne. One of his first royal acts was to execute all of his royal kin. In the years that followed, he also executed many past supporters of Shaka in order to secure his position. One exception to these purges was Mpande, another half-brother, who was considered too weak to be a threat at the time.

Clashes with the Voortrekkers and the ascendancy of Mpande

In October 1837, the Voortrekker leader Piet Retief visited Dingane at his royal kraal to negotiate a land deal for the voortrekkers. In November, about 1,000 Voortrekker wagons began descending the Drakensberg mountains from the Orange Free State into what is now KwaZulu-Natal.

Dingane asked that Retief and his party retrieve some cattle stolen from him by a local chief. This Retief and his men did, returning on February 3 1838. The next day, a treaty was signed, wherein Dingane ceded all the land south of the Tugela River to the Mzimvubu River to the Voortrekkers. Celebrations followed. On February 6, at the end of the celebrations, Retief's party were invited to a dance, and asked to leave their weapons behind. At the peak of the dance, Dingane leapt to his feet and yelled "Bambani abathakathi!" (isiZulu for "Seize the wizards"). Retief and his men were overpowered, taken to the nearby hill kwaMatiwane, and executed. Some believe that they were killed for withholding some of the cattle they recovered, but it is likely that the deal was a ploy to overpower the Voortrekkers. Dingane's army then attacked and massacred a group of 250 Voortrekker men, women and children camped nearby. The site of this massacre is today called Weenen, (Afrikaans for "to weep").

The remaining Voortrekkers elected a new leader, Andries Pretorius, and Dingane suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Blood River on December 16 1838, when he attacked a group of 470 Voortrekker settlers led by Pretorius.

Following his defeat, Dingane burned his royal household and fled north. Mpande, the half-brother who had been spared from Dingane's purges, defected with 17,000 followers, and, together with Pretorius and the Voortrekkers, went to war with Dingane. Dingane was assassinated near the modern Swaziland border. Mpande then took over rulership of the Zulu nation.

Succession of Cetshwayo

Following the campaign against Dingane, in 1839 the Voortrekkers, under Pretorius, formed the Boer republic of Natalia, south of the Tugela, and west of the British settlement of Port Natal (now Durban). Mpande and Pretorius maintained peaceful relations. However, in 1842, war broke out between the British and the Boers, resulting in the British annexation of Natalia. Mpande shifted his allegiance to the British, and remained on good terms with them.

In 1843, Mpande ordered a purge of perceived dissidents within his kingdom. This resulted in numerous deaths, and the fleeing of thousands of refugees into neighbouring areas (including the British-controlled Natal). Many of these refugees fled with cattle. Mpande began raiding the surrounding areas, culminating in the invasion of Swaziland in 1852. However, the British pressured him into withdrawing, which he did shortly.

At this time, a battle for the succession broke out between two of Mpande's sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi. This culminated in 1856 with the Battle of Ndondakusuka , which left Mbuyazi dead. Cetshwayo then set about usurping his father's authority. When Mpande died of old age in 1872, Cetshwayo took over as ruler.

Anglo-Zulu War

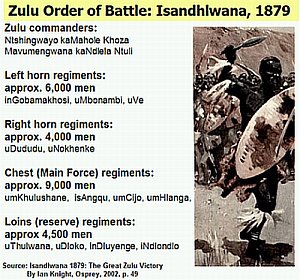

Main article: Anglo-Zulu WarOn December 11, 1878, agents of the British delivered an ultimatum to 14 chiefs representing Cetshwayo. The terms of the ultimatum were unacceptable to Cetshwayo. British forces crossed the Tugela river at the end of December 1878. The war took place in 1879. Early in the war, the Zulus defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22, but were defeated later that day at Rorke's Drift. The war ended in Zulu defeat at the Battle of Ulundi on July 4.

Division and the death of Cetshwayo

Cetshwayo was captured a month after his defeat, and then exiled to Cape Town. The British passed rule of the Zulu kingdom onto 13 "kinglets", each with his own subkingdom. Conflict soon erupted between these subkingdoms, and in 1882, Cetshwayo was allowed to visit England. He had audiences with Queen Victoria, and other famous personages, before being allowed to return to Zululand, to be reinstated as king.

In 1883, Cetshwayo was put in place as king over a buffer reserve territory, much reduced from his original kingdom. Later that year, however, Cetshwayo was attacked at Ulundi by Zibhebhu, one of the 13 kinglets, supported by Boer mercenaries. Cetshwayo was wounded and fled. Cetshwayo died in February 1884, possibly poisoned. His son, Dinuzulu, then 15, inherited the throne.

Dinuzulu's Volunteers and final absorption into Cape Colony

Dinuzulu recruited Boer mercenaries of his own, promising them land in return for their aid. These mercenaries called themselves "Dinuzulu's Volunteers", and were led by Louis Botha. Dinuzulu's Volunteers defeated Zibhebhu in 1884, and duly demanded their land. They were granted about half of Zululand individually as farms, and formed an independent republic. This alarmed the British, who then annexed Zululand in 1887. Dinuzulu became involved in later conflicts with rivals. In 1906 Dinuzulu was accused of being behind the Bambatha Rebellion. He was arrested and put on trial by the British for "high treason and public violence". In 1909, he was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment on St Helena island. When the Union of South Africa was formed, Louis Botha became its first prime minister, and he arranged for his old ally Dinuzulu to live in exile on a farm in the Transvaal, where he died in 1913.

Dinuzulu's son Solomon kaDinuzulu was never recognized by South African authorities as the Zulu king, only as a local chief, but he was increasingly regarded as king by chiefs, by political intellectuals such as John Langalibalele Dube and by ordinary Zulu people. In 1923, Solomon founded the organization Inkatha YaKwaZulu to promote his royal claims, which became moribund and then was revived in the 1970s by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, chief minister of the KwaZulu bantustan. In December 1951, Solomon's son Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon was officially recognized as the Paramount Chief of the Zulu people, but real power over ordinary Zulu people lay with white South African officials working through local chiefs who could be removed from office for failure to cooperate.

External links

- Afropop Worldwide's public radio program on Zulu Music, "The Zulu Factor"

- People of Africa, Zulu marriage explained

- An article on Piet Retief, including his interactions with Dingane

- History section of the official page for the Zululand region

- Human Rights Watch report on KwaZulu, just before the 1994 elections - This includes detailed, well-referenced, sections on recent Zulu history.

Sources

- Bryant, Alfred T. (1964). A History of the Zulu and Neighbouring Tribes. Cape Town: C. Struik. p. 157.

- Morris, Donald R. (1965). The Washing of the Spears: the Rise of the Zulu Nation. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 655.

References

- Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, by Ian Knight, Osprey: 2002, pp. 49, See also Donald Morris, The Washing of The Spears, Simon and Schuster, 1965, p. 263-382