| Revision as of 12:54, 18 September 2009 view sourceRobbot (talk | contribs)94,607 editsm robot Adding: mhr:Географий← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:36, 20 October 2009 view source Abductive (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers128,626 editsm Adding a few internal links from an online link suggesting tool.Next edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| {{TOCright}} | {{TOCright}} | ||

| '''Geography''' (from ] ''γεωγραφία'' - ''geographia'', lit. "earth describe-write"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=geography |title=Online Etymology Dictionary |publisher=Etymonline.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-17}}</ref>) is the study of the ] and its lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena.<ref>{{cite web |title=Geography |work=The American Heritage Dictionary/ of the English Language, Fourth Edition |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/geography |accessdate=October 9 2006|dateformat=mdy }}</ref> A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was ] (276-194 B.C.). Four historical traditions in geographical research are the ] of natural and human phenomena (geography as a study of distribution), area studies (places and regions), study of man-land relationship, and research in ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pattison |first=W.D. |year=1990 |title=The Four Traditions of Geography |journal=Journal of Geography |volume=89 |issue=5 |pages=pp. 202–6 |url=http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/~kclarke/G200B/four_20traditions_20of_20geography.pdf |issn=0022-1341 |doi=10.1080/00221349008979196 }} Reprint of a 1964 article.</ref> Nonetheless, modern geography is an all-encompassing discipline that foremost seeks to understand the Earth and all of its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but how they have changed and come to be. As "the bridge between the human and physical |

'''Geography''' (from ] ''γεωγραφία'' - ''geographia'', lit. "earth describe-write"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=geography |title=Online Etymology Dictionary |publisher=Etymonline.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-17}}</ref>) is the study of the ] and its lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena.<ref>{{cite web |title=Geography |work=The American Heritage Dictionary/ of the English Language, Fourth Edition |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/geography |accessdate=October 9 2006|dateformat=mdy }}</ref> A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was ] (276-194 B.C.). Four historical traditions in geographical research are the ] of natural and human phenomena (geography as a study of distribution), ] (places and regions), study of man-land relationship, and research in ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pattison |first=W.D. |year=1990 |title=The Four Traditions of Geography |journal=Journal of Geography |volume=89 |issue=5 |pages=pp. 202–6 |url=http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/~kclarke/G200B/four_20traditions_20of_20geography.pdf |issn=0022-1341 |doi=10.1080/00221349008979196 }} Reprint of a 1964 article.</ref> Nonetheless, modern geography is an all-encompassing discipline that foremost seeks to understand the Earth and all of its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but how they have changed and come to be. As "the bridge between the human and ]s," geography is divided into two main branches—] and ].<ref>http://web.clas.ufl.edu/users/morgans/lecture_2.prn.pdf</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/1b.html |title=1(b). Elements of Geography |publisher=Physicalgeography.net |date= |accessdate=2009-04-17}}</ref> | ||

| ==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| {{cquote2|...mere names of places...are not geography...know by heart a whole gazetteer full of them would not, in itself, constitute anyone a ]. Geography has higher aims than this: it seeks to classify phenomena (alike of the natural and of the political world, in so far as it treats of the latter), to compare, to generalize, to ascend from effects to causes, and, in doing so, to trace out the great laws of nature and to mark their influences upon man. This is 'a description of the world'—that is Geography. In a word Geography is a Science—a thing not of mere names but of argument and reason, of cause and effect.<ref>Hughes, William. (1863). ''The Study of Geography''. Lecture delivered at King's College, London by Sir Marc Alexander. Quoted in {{cite book |last=Baker |first=J.N.L |year=1963 |title=The History of Geography |publisher=Basil Blackwell |location=Oxford |pages=p. 66}}</ref>|William Hughes, 1863}} | {{cquote2|...mere names of places...are not geography...know by heart a whole gazetteer full of them would not, in itself, constitute anyone a ]. Geography has higher aims than this: it seeks to classify phenomena (alike of the natural and of the political world, in so far as it treats of the latter), to compare, to generalize, to ascend from effects to causes, and, in doing so, to trace out the great laws of nature and to mark their influences upon man. This is 'a description of the world'—that is Geography. In a word Geography is a Science—a thing not of mere names but of argument and reason, of cause and effect.<ref>Hughes, William. (1863). ''The Study of Geography''. Lecture delivered at King's College, London by Sir Marc Alexander. Quoted in {{cite book |last=Baker |first=J.N.L |year=1963 |title=The History of Geography |publisher=Basil Blackwell |location=Oxford |pages=p. 66}}</ref>|William Hughes, 1863}} | ||

| Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into two main sub fields: ] and ]. The former focuses largely on the built environment and how space is created, viewed and managed by humans as well as the influence humans have on the space they occupy. The latter examines the natural environment and how the ], ] & life, ], ], and ]s are produced and interact.<ref>{{cite web |title=What is geography? |work=AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and related Geographical Sciences |publisher=Association of American Geographers |url=http://www.aag.org/Careers/What_is_geog.html |accessdate=October 9 2006|dateformat=mdy }}</ref> As a result of the two subfields using different approaches a third field has emerged, which is ]. Environmental geography combines physical and human geography and looks at the interactions between the environment and humans.<ref name="Hayes-Bohanan"/> | Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into two main sub fields: ] and ]. The former focuses largely on the ] and how space is created, viewed and managed by humans as well as the influence humans have on the space they occupy. The latter examines the natural environment and how the ], ] & life, ], ], and ]s are produced and interact.<ref>{{cite web |title=What is geography? |work=AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and related Geographical Sciences |publisher=Association of American Geographers |url=http://www.aag.org/Careers/What_is_geog.html |accessdate=October 9 2006|dateformat=mdy }}</ref> As a result of the two subfields using different approaches a third field has emerged, which is ]. Environmental geography combines physical and human geography and looks at the interactions between the environment and humans.<ref name="Hayes-Bohanan"/> | ||

| ==Branches of geography== | ==Branches of geography== | ||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

| Cartography studies the representation of the Earth's surface with abstract symbols (map making). Although other subdisciplines of geography rely on maps for presenting their analyses, the actual making of maps is abstract enough to be regarded separately. Cartography has grown from a collection of drafting techniques into an actual science. | Cartography studies the representation of the Earth's surface with abstract symbols (map making). Although other subdisciplines of geography rely on maps for presenting their analyses, the actual making of maps is abstract enough to be regarded separately. Cartography has grown from a collection of drafting techniques into an actual science. | ||

| Cartographers must learn ] and ergonomics to understand which symbols convey information about the Earth most effectively, and ] to induce the readers of their maps to act on the information. They must learn ] and fairly advanced ] to understand how the shape of the Earth affects the distortion of map symbols projected onto a flat surface for viewing. It can be said, without much controversy, that cartography is the seed from which the larger field of geography grew. Most geographers will cite a childhood fascination with maps as an early sign they would end up in the field. | Cartographers must learn ] and ergonomics to understand which symbols convey information about the Earth most effectively, and ] to induce the readers of their maps to act on the information. They must learn ] and fairly advanced ] to understand how the ] affects the distortion of map symbols projected onto a flat surface for viewing. It can be said, without much controversy, that cartography is the seed from which the larger field of geography grew. Most geographers will cite a childhood fascination with maps as an early sign they would end up in the field. | ||

| ===Geographic information systems=== | ===Geographic information systems=== | ||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: ] software (Idrisi, Clark Labs).]] --> | <!-- Deleted image removed: ] software (Idrisi, Clark Labs).]] --> | ||

| <!-- the section's use of a singular verb for a seemingly plural noun is intentional. The name of the academic subject is "Geographic information systems". If you didn't care about parallel construction, you could precede the following with THE SUBJECT OF ---> | <!-- the section's use of a singular verb for a seemingly plural noun is intentional. The name of the academic subject is "Geographic information systems". If you didn't care about parallel construction, you could precede the following with THE SUBJECT OF ---> | ||

| Geographic information systems (GIS) deal with the storage of information about the Earth for automatic retrieval by a computer, in an accurate manner appropriate to the information's purpose. In addition to all of the other subdisciplines of geography, GIS specialists must understand ] and ] systems. GIS has revolutionized the field of cartography; nearly all mapmaking is now done with the assistance of some form of GIS software. GIS also refers to the science of using GIS software and GIS techniques to represent, analyze and predict spatial relationships. In this context, GIS stands for Geographic Information Science. | Geographic information systems (GIS) deal with the storage of information about the Earth for automatic retrieval by a computer, in an accurate manner appropriate to the information's purpose. In addition to all of the other subdisciplines of geography, GIS specialists must understand ] and ] systems. GIS has revolutionized the field of cartography; nearly all mapmaking is now done with the assistance of some form of ]. GIS also refers to the science of using GIS software and GIS techniques to represent, analyze and predict spatial relationships. In this context, GIS stands for Geographic Information Science. | ||

| ===Remote sensing=== | ===Remote sensing=== | ||

| {{main|Remote sensing}} | {{main|Remote sensing}} | ||

| Remote sensing is the science of obtaining information about Earth features from measurements made at a distance. Remotely sensed data comes in many forms such as ], ] and data obtained from hand-held sensors. Geographers increasingly use remotely sensed data to obtain information about the Earth's land surface, ocean and atmosphere because it: a) supplies objective information at a variety of spatial scales (local to global), b) provides a synoptic view of the area of interest, c) allows access to distant and/or inaccessible sites, d) provides spectral information outside the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, and e) facilitates studies of how features/areas change over time. Remotely sensed data may be analyzed either independently of, or in conjunction with, other digital data layers (e.g., in a Geographic Information System). | Remote sensing is the science of obtaining information about Earth features from measurements made at a distance. Remotely sensed data comes in many forms such as ], ] and data obtained from hand-held sensors. Geographers increasingly use remotely sensed data to obtain information about the Earth's ], ocean and atmosphere because it: a) supplies objective information at a variety of spatial scales (local to global), b) provides a synoptic view of the area of interest, c) allows access to distant and/or inaccessible sites, d) provides spectral information outside the visible portion of the ], and e) facilitates studies of how features/areas change over time. Remotely sensed data may be analyzed either independently of, or in conjunction with, other digital data layers (e.g., in a Geographic Information System). | ||

| ===Geographic quantitative methods=== | ===Geographic quantitative methods=== | ||

| {{main|Geostatistics}} | {{main|Geostatistics}} | ||

| ] deal with quantitative data analysis, specifically the application of statistical methodology to the exploration of geographic phenomena. Geostatistics is used extensively in a variety of fields including: ], ], ] exploration, weather analysis, ], ], and ]. The mathematical basis for geostatistics derives from ], ] and ], and a variety of other subjects. Applications of geostatistics rely heavily on ]s, particularly for the ] (estimate) of unmeasured points. Geographers are making notable contributions to the method of quantitative techniques. | ] deal with ] analysis, specifically the application of statistical methodology to the exploration of geographic phenomena. Geostatistics is used extensively in a variety of fields including: ], ], ] exploration, weather analysis, ], ], and ]. The mathematical basis for geostatistics derives from ], ] and ], and a variety of other subjects. Applications of geostatistics rely heavily on ]s, particularly for the ] (estimate) of unmeasured points. Geographers are making notable contributions to the method of quantitative techniques. | ||

| ===Geographic qualitative methods=== | ===Geographic qualitative methods=== | ||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

| The ideas of ] (c. 610 B.C.-c. 545 B.C.), considered by later Greek writers to be the true founder of geography, come to us through fragments quoted by his successors. Anaximander is credited with the invention of the gnomon,the simple yet efficient Greek instrument that allowed the early measurement of latitude. Thales, Anaximander is also credited with the prediction of eclipses. The foundations of geography can be traced to the ancient cultures, such as the ancient, medieval, and early modern ]. The ], who were the first to explore geography as both ] and ], achieved this through ], ], and ], or through ]. There is some debate about who was the first person to assert that the Earth is spherical in shape, with the credit going either to ] or ]. ] was able to demonstrate that the profile of the Earth was circular by explaining ]s. However, he still believed that the Earth was a flat disk, as did many of his contemporaries. One of the first estimates of the radius of the Earth was made by ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jean-Louis and Monique Tassoul |title=A Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=London |year=1920 }}</ref> | The ideas of ] (c. 610 B.C.-c. 545 B.C.), considered by later Greek writers to be the true founder of geography, come to us through fragments quoted by his successors. Anaximander is credited with the invention of the gnomon,the simple yet efficient Greek instrument that allowed the early measurement of latitude. Thales, Anaximander is also credited with the prediction of eclipses. The foundations of geography can be traced to the ancient cultures, such as the ancient, medieval, and early modern ]. The ], who were the first to explore geography as both ] and ], achieved this through ], ], and ], or through ]. There is some debate about who was the first person to assert that the Earth is spherical in shape, with the credit going either to ] or ]. ] was able to demonstrate that the profile of the Earth was circular by explaining ]s. However, he still believed that the Earth was a flat disk, as did many of his contemporaries. One of the first estimates of the radius of the Earth was made by ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jean-Louis and Monique Tassoul |title=A Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=London |year=1920 }}</ref> | ||

| The first rigorous system of latitude and longitude lines is credited to ]. He employed a ] system that was derived from ]. The parallels and meridians were sub-divided into 360°, with each degree further subdivided 60′ (]). To measure the longitude at different location on Earth, he suggested using eclipses to determine the relative difference in time.<ref>{{cite web |year=2001 |url=http://astrogeology.usgs.gov/HotTopics/index.php?/archives/147-Names-for-the-Columbia-astronauts-provisionally-approved.html |title=Hipparcos of Rhodes |publisher=Technology Museum of Thessaloniki|accessdate=2006-10-16 }}</ref> The extensive mapping by the ] as they explored new lands would later provide a high level of information for ] to construct detailed ]es. He extended the work of ], using a grid system on his maps and adopting a length of 56.5 ]s for a degree.<ref>{{cite web |last=Sullivan |first=Dan |year=2000 |url=http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~cherlin/History/Papers2000/sullivan.html |title=Mapmaking and its History |publisher=Rutgers University |accessdate=2006-10-16 }}</ref> | The first rigorous system of ] lines is credited to ]. He employed a ] system that was derived from ]. The parallels and meridians were sub-divided into 360°, with each degree further subdivided 60′ (]). To measure the longitude at different location on Earth, he suggested using eclipses to determine the relative difference in time.<ref>{{cite web |year=2001 |url=http://astrogeology.usgs.gov/HotTopics/index.php?/archives/147-Names-for-the-Columbia-astronauts-provisionally-approved.html |title=Hipparcos of Rhodes |publisher=Technology Museum of Thessaloniki|accessdate=2006-10-16 }}</ref> The extensive mapping by the ] as they explored new lands would later provide a high level of information for ] to construct detailed ]es. He extended the work of ], using a grid system on his maps and adopting a length of 56.5 ]s for a degree.<ref>{{cite web |last=Sullivan |first=Dan |year=2000 |url=http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~cherlin/History/Papers2000/sullivan.html |title=Mapmaking and its History |publisher=Rutgers University |accessdate=2006-10-16 }}</ref> | ||

| From the 3rd century onwards, ] methods of geographical study and writing of geographical literature became much more complex than what was found in Europe at the time (until the 13th century).<ref name="needham volume 3 512"/> Chinese geographers such as ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] wrote important treatises, yet by the 17th century, advanced ideas and methods of Western-style geography were adopted in China. | From the 3rd century onwards, ] methods of geographical study and writing of geographical literature became much more complex than what was found in Europe at the time (until the 13th century).<ref name="needham volume 3 512"/> Chinese geographers such as ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] wrote important treatises, yet by the 17th century, advanced ideas and methods of Western-style geography were adopted in China. | ||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

| During the ], the ] led to a shift in the evolution of geography from ] to the ].<ref name="needham volume 3 512">Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 512.</ref> ] such as ] produced detailed world maps (such as ]), while other geographers such as ], ], ] and ] provided detailed accounts of their journeys and the geography of the regions they visited. Turkish geographer, ] drew a world map on a linguistic basis, and later so did ] (]). Further, Islamic scholars translated and ] the earlier works of the ] and ] and established the ] in ] for this purpose.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.islamicity.com/education/ihame/default.asp?Destination=/education/ihame/20.asp |title=Education |publisher=IslamiCity.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-17}}</ref> ], originally from ], founded the "Balkhī school" of terrestrial mapping in ].<ref name = E61-3>E. Edson and Emilie Savage-Smith, ''Medieval Views of the Cosmos'', pp. 61-3, Bodleian Library, ]</ref> Suhrāb, a late tenth century Muslim geographer, accompanied a book of geographical coordinates with instructions for making a rectangular world map, with ] or cylindrical equidistant projection.<ref name = E61-3/> In the early 11th century, ] hypothesized on the ] causes of ]s in '']'' (1027). | During the ], the ] led to a shift in the evolution of geography from ] to the ].<ref name="needham volume 3 512">Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 512.</ref> ] such as ] produced detailed world maps (such as ]), while other geographers such as ], ], ] and ] provided detailed accounts of their journeys and the geography of the regions they visited. Turkish geographer, ] drew a world map on a linguistic basis, and later so did ] (]). Further, Islamic scholars translated and ] the earlier works of the ] and ] and established the ] in ] for this purpose.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.islamicity.com/education/ihame/default.asp?Destination=/education/ihame/20.asp |title=Education |publisher=IslamiCity.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-17}}</ref> ], originally from ], founded the "Balkhī school" of terrestrial mapping in ].<ref name = E61-3>E. Edson and Emilie Savage-Smith, ''Medieval Views of the Cosmos'', pp. 61-3, Bodleian Library, ]</ref> Suhrāb, a late tenth century Muslim geographer, accompanied a book of geographical coordinates with instructions for making a rectangular world map, with ] or cylindrical equidistant projection.<ref name = E61-3/> In the early 11th century, ] hypothesized on the ] causes of ]s in '']'' (1027). | ||

| ] (976-1048) first described a polar equi-] of the ].<ref>David A. King (1996), "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '']'', Vol. 1, p. 128-184 . ], London and New York.</ref> He was regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the ] and ]. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of ] and ]. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of ]s, depths of ]s, and expanse of the ]. He also discussed ] and the ] of the ]. He hypothesized that roughly a quarter of the Earth's surface is habitable by ]s.<ref name=Bill>{{Harvard reference |last=Scheppler |first=Bill |year=2006 |title=Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century |publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |isbn=1404205128 |pp=41-2}}</ref> He also calculated the ] of Kath, ], using the maximum altitude of the Sun, and solved a complex ] equation in order to accurately compute the ]'s ], which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.<ref name=Khwarizm>{{cite web|url=http://muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=482|title=Khwarizm|publisher=Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation|accessdate=2008-01-22}}</ref><ref>James S. Aber (2003). Alberuni calculated the Earth's circumference at a small town of Pind Dadan Khan, District Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan., ].</ref> His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the ] was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method of using ] calculations based on the angle between a ] and ] top which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.<ref>Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), ''Avicenna'', p. 31, ], ISBN 041501929X.</ref> He also published a study of ]s, '']'', which included a method for projecting a ] on a ].<ref>{{Harvard reference |last=Scheppler |first=Bill |year=2006 |title=Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century |publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |isbn=1404205128 |pp=42-3}}</ref> | ] (976-1048) first described a polar equi-] of the ].<ref>David A. King (1996), "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '']'', Vol. 1, p. 128-184 . ], London and New York.</ref> He was regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the ] and ]. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of ] and ]. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of ]s, depths of ]s, and expanse of the ]. He also discussed ] and the ] of the ]. He hypothesized that roughly a quarter of the Earth's surface is habitable by ]s.<ref name=Bill>{{Harvard reference |last=Scheppler |first=Bill |year=2006 |title=Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century |publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |isbn=1404205128 |pp=41-2}}</ref> He also calculated the ] of Kath, ], using the maximum altitude of the Sun, and solved a complex ] equation in order to accurately compute the ]'s ], which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.<ref name=Khwarizm>{{cite web|url=http://muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=482|title=Khwarizm|publisher=Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation|accessdate=2008-01-22}}</ref><ref>James S. Aber (2003). Alberuni calculated the Earth's circumference at a small town of Pind Dadan Khan, District Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan., ].</ref> His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the ] was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, ] developed a new method of using ] calculations based on the angle between a ] and ] top which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.<ref>Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), ''Avicenna'', p. 31, ], ISBN 041501929X.</ref> He also published a study of ]s, '']'', which included a method for projecting a ] on a ].<ref>{{Harvard reference |last=Scheppler |first=Bill |year=2006 |title=Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century |publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |isbn=1404205128 |pp=42-3}}</ref> | ||

| ], one of the early pioneers of geography]] | ], one of the early pioneers of geography]] | ||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

| The European ] during the 16th and 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as ], ] and ], revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail, and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | The European ] during the 16th and 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as ], ] and ], revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail, and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | ||

| The 18th and 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete academic discipline and became part of a typical ] curriculum in ] (especially ] and ]). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century with the foundations of the ] in 1821,<ref>{{cite web | The 18th and 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete ] and became part of a typical ] curriculum in ] (especially ] and ]). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century with the foundations of the ] in 1821,<ref>{{cite web | ||

| |url=http://www.socgeo.org/index.html | |url=http://www.socgeo.org/index.html | ||

| |title=Société de Géographie, Paris, France | |title=Société de Géographie, Paris, France | ||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

| * ] (1769–1859) - Considered Father of modern geography, published the Kosmos and founder of the sub-field biogeography. | * ] (1769–1859) - Considered Father of modern geography, published the Kosmos and founder of the sub-field biogeography. | ||

| * ] (1779-1859) - Considered Father of modern geography. Occupied the first chair of geography at Berlin University. | * ] (1779-1859) - Considered Father of modern geography. Occupied the first chair of geography at Berlin University. | ||

| * ] (1807-1884) - noted the structure of glaciers and advanced understanding in glacier motion, especially in fast ice flow. | * ] (1807-1884) - noted the structure of glaciers and advanced understanding in ], especially in fast ice flow. | ||

| * ] (1850-1934) - father of American geography and developer of the cycle of erosion. | * ] (1850-1934) - father of American geography and developer of the ]. | ||

| * ] (1845-1918) - founder of the French school of geopolitics and wrote the principles of human geography. | * ] (1845-1918) - founder of the French school of geopolitics and wrote the principles of human geography. | ||

| * Sir ] (1861-1947) - Co-founder of the ], ] | * Sir ] (1861-1947) - Co-founder of the ], ] | ||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

| * ] (1944-) - prominent GIS scholar and winner of the RGS founder's medal in 2003. | * ] (1944-) - prominent GIS scholar and winner of the RGS founder's medal in 2003. | ||

| * ] (1944-) - Key scholar in the space and places of ] and its pluralities, winner of the ]. | * ] (1944-) - Key scholar in the space and places of ] and its pluralities, winner of the ]. | ||

| * ] (1949-) - originator of non-representational theory. | * ] (1949-) - originator of ]. | ||

| ==Geographical institutions and societies== | ==Geographical institutions and societies== | ||

Revision as of 18:36, 20 October 2009

For other uses, see Geography (disambiguation). "Geographical" redirects here. For the magazine of the Royal Geographical Society, see Geographical (magazine).

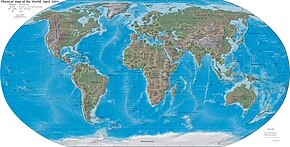

Geography (from Greek γεωγραφία - geographia, lit. "earth describe-write") is the study of the Earth and its lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes (276-194 B.C.). Four historical traditions in geographical research are the spatial analysis of natural and human phenomena (geography as a study of distribution), area studies (places and regions), study of man-land relationship, and research in earth sciences. Nonetheless, modern geography is an all-encompassing discipline that foremost seeks to understand the Earth and all of its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but how they have changed and come to be. As "the bridge between the human and physical sciences," geography is divided into two main branches—human geography and physical geography.

Introduction

Traditionally, geographers have been viewed the same way as cartographers and people who study place names and numbers. Although many geographers are trained in toponymy and cartology, this is not their main preoccupation. Geographers study the spatial and temporal distribution of phenomena, processes and features as well as the interaction of humans and their environment. As space and place affect a variety of topics such as economics, health, climate, plants and animals, geography is highly interdisciplinary.

...mere names of places...are not geography...know by heart a whole gazetteer full of them would not, in itself, constitute anyone a geographer. Geography has higher aims than this: it seeks to classify phenomena (alike of the natural and of the political world, in so far as it treats of the latter), to compare, to generalize, to ascend from effects to causes, and, in doing so, to trace out the great laws of nature and to mark their influences upon man. This is 'a description of the world'—that is Geography. In a word Geography is a Science—a thing not of mere names but of argument and reason, of cause and effect.

— William Hughes, 1863

Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into two main sub fields: human geography and physical geography. The former focuses largely on the built environment and how space is created, viewed and managed by humans as well as the influence humans have on the space they occupy. The latter examines the natural environment and how the climate, vegetation & life, soil, water, and landforms are produced and interact. As a result of the two subfields using different approaches a third field has emerged, which is environmental geography. Environmental geography combines physical and human geography and looks at the interactions between the environment and humans.

Branches of geography

Physical geography

Main article: Physical geographyPhysical geography (or physiogeography) focuses on geography as an Earth science. It aims to understand the physical lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, pedosphere, and global flora and fauna patterns (biosphere). Physical geography can be divided into the following broad categories:

Human geography

Main article: Human geographyHuman geography is a branch of geography that focuses on the study of patterns and processes that shape human interaction with various environments. It encompasses human, political, cultural, social, and economic aspects. While the major focus of human geography is not the physical landscape of the Earth (see physical geography), it is hardly possible to discuss human geography without referring to the physical landscape on which human activities are being played out, and environmental geography is emerging as a link between the two. Human geography can be divided into many broad categories, such as:

Various approaches to the study of human geography have also arisen through time and include:

Environmental geography

Main article: Environmental geographyEnvironmental geography is the branch of geography that describes the spatial aspects of interactions between humans and the natural world. It requires an understanding of the traditional aspects of physical and human geography, as well as the ways in which human societies conceptualize the environment.

Environmental geography has emerged as a bridge between human and physical geography as a result of the increasing specialisation of the two sub-fields. Furthermore, as human relationship with the environment has changed as a result of globalization and technological change a new approach was needed to understand the changing and dynamic relationship. Examples of areas of research in environmental geography include emergency management, environmental management, sustainability, and political ecology.

Geomatics

Main article: Geomatics

Geomatics is a branch of geography that has emerged since the quantitative revolution in geography in the mid 1950s. Geomatics involves the use of traditional spatial techniques used in cartography and topography and their application to computers. Geomatics has become a widespread field with many other disciplines using techniques such as GIS and remote sensing. Geomatics has also led to a revitalization of some geography departments especially in Northern America where the subject had a declining status during the 1950s.

Geomatics encompasses a large area of fields involved with spatial analysis, such as Cartography, Geographic information systems (GIS), Remote sensing, and Global positioning systems (GPS).

Regional geography

Main article: Regional geographyRegional geography is a branch of geography that studies the regions of all sizes across the Earth. It has a prevailing descriptive character. The main aim is to understand or define the uniqueness or character of a particular region which consists of natural as well as human elements. Attention is paid also to regionalization which covers the proper techniques of space delimitation into regions.

Regional geography is also considered as a certain approach to study in geographical sciences (similar to quantitative or critical geographies, for more information see History of geography).

Related fields

- Urban planning, regional planning and spatial planning: use the science of geography to assist in determining how to develop (or not develop) the land to meet particular criteria, such as safety, beauty, economic opportunities, the preservation of the built or natural heritage, and so on. The planning of towns, cities, and rural areas may be seen as applied geography.

- Regional science: In the 1950s the regional science movement led by Walter Isard arose, to provide a more quantitative and analytical base to geographical questions, in contrast to the descriptive tendencies of traditional geography programs. Regional science comprises the body of knowledge in which the spatial dimension plays a fundamental role, such as regional economics, resource management, location theory, urban and regional planning, transport and communication, human geography, population distribution, landscape ecology, and environmental quality.

- Interplanetary Sciences: While the discipline of geography is normally concerned with the Earth, the term can also be informally used to describe the study of other worlds, such as the planets of the Solar System and even beyond. The study of systems larger than the earth itself usually forms part of Astronomy or Cosmology. The study of other planets is usually called planetary science. Alternative terms such as Areology (the study of Mars) have been proposed, but are not widely used.

Geographical techniques

As spatial interrelationships are key to this synoptic science, maps are a key tool. Classical cartography has been joined by a more modern approach to geographical analysis, computer-based geographic information systems (GIS).

In their study, geographers use four interrelated approaches:

- Systematic - Groups geographical knowledge into categories that can be explored globally.

- Regional - Examines systematic relationships between categories for a specific region or location on the planet.

- Descriptive - Simply specifies the locations of features and populations.

- Analytical - Asks why we find features and populations in a specific geographic area.

Cartography

Main article: CartographyCartography studies the representation of the Earth's surface with abstract symbols (map making). Although other subdisciplines of geography rely on maps for presenting their analyses, the actual making of maps is abstract enough to be regarded separately. Cartography has grown from a collection of drafting techniques into an actual science.

Cartographers must learn cognitive psychology and ergonomics to understand which symbols convey information about the Earth most effectively, and behavioral psychology to induce the readers of their maps to act on the information. They must learn geodesy and fairly advanced mathematics to understand how the shape of the Earth affects the distortion of map symbols projected onto a flat surface for viewing. It can be said, without much controversy, that cartography is the seed from which the larger field of geography grew. Most geographers will cite a childhood fascination with maps as an early sign they would end up in the field.

Geographic information systems

Main article: Geographic information systemGeographic information systems (GIS) deal with the storage of information about the Earth for automatic retrieval by a computer, in an accurate manner appropriate to the information's purpose. In addition to all of the other subdisciplines of geography, GIS specialists must understand computer science and database systems. GIS has revolutionized the field of cartography; nearly all mapmaking is now done with the assistance of some form of GIS software. GIS also refers to the science of using GIS software and GIS techniques to represent, analyze and predict spatial relationships. In this context, GIS stands for Geographic Information Science.

Remote sensing

Main article: Remote sensingRemote sensing is the science of obtaining information about Earth features from measurements made at a distance. Remotely sensed data comes in many forms such as satellite imagery, aerial photography and data obtained from hand-held sensors. Geographers increasingly use remotely sensed data to obtain information about the Earth's land surface, ocean and atmosphere because it: a) supplies objective information at a variety of spatial scales (local to global), b) provides a synoptic view of the area of interest, c) allows access to distant and/or inaccessible sites, d) provides spectral information outside the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, and e) facilitates studies of how features/areas change over time. Remotely sensed data may be analyzed either independently of, or in conjunction with, other digital data layers (e.g., in a Geographic Information System).

Geographic quantitative methods

Main article: GeostatisticsGeostatistics deal with quantitative data analysis, specifically the application of statistical methodology to the exploration of geographic phenomena. Geostatistics is used extensively in a variety of fields including: hydrology, geology, petroleum exploration, weather analysis, urban planning, logistics, and epidemiology. The mathematical basis for geostatistics derives from cluster analysis, linear discriminant analysis and non-parametric statistical tests, and a variety of other subjects. Applications of geostatistics rely heavily on geographic information systems, particularly for the interpolation (estimate) of unmeasured points. Geographers are making notable contributions to the method of quantitative techniques.

Geographic qualitative methods

Main article: EthnographyGeographic qualitative methods, or ethnographical; research techniques, are used by human geographers. In cultural geography there is a tradition of employing qualitative research techniques also used in anthropology and sociology. Participant observation and in-depth interviews provide human geographers with qualitative data.

History of geography

Main article: History of geography| History of geography |

|---|

|

The ideas of Anaximander (c. 610 B.C.-c. 545 B.C.), considered by later Greek writers to be the true founder of geography, come to us through fragments quoted by his successors. Anaximander is credited with the invention of the gnomon,the simple yet efficient Greek instrument that allowed the early measurement of latitude. Thales, Anaximander is also credited with the prediction of eclipses. The foundations of geography can be traced to the ancient cultures, such as the ancient, medieval, and early modern Chinese. The Greeks, who were the first to explore geography as both art and science, achieved this through Cartography, Philosophy, and Literature, or through Mathematics. There is some debate about who was the first person to assert that the Earth is spherical in shape, with the credit going either to Parmenides or Pythagoras. Anaxagoras was able to demonstrate that the profile of the Earth was circular by explaining eclipses. However, he still believed that the Earth was a flat disk, as did many of his contemporaries. One of the first estimates of the radius of the Earth was made by Eratosthenes.

The first rigorous system of latitude and longitude lines is credited to Hipparchus. He employed a sexagesimal system that was derived from Babylonian mathematics. The parallels and meridians were sub-divided into 360°, with each degree further subdivided 60′ (minutes). To measure the longitude at different location on Earth, he suggested using eclipses to determine the relative difference in time. The extensive mapping by the Romans as they explored new lands would later provide a high level of information for Ptolemy to construct detailed atlases. He extended the work of Hipparchus, using a grid system on his maps and adopting a length of 56.5 miles for a degree.

From the 3rd century onwards, Chinese methods of geographical study and writing of geographical literature became much more complex than what was found in Europe at the time (until the 13th century). Chinese geographers such as Liu An, Pei Xiu, Jia Dan, Shen Kuo, Fan Chengda, Zhou Daguan, and Xu Xiake wrote important treatises, yet by the 17th century, advanced ideas and methods of Western-style geography were adopted in China.

During the Middle Ages, the fall of the Roman empire led to a shift in the evolution of geography from Europe to the Islamic world. Muslim geographers such as Muhammad al-Idrisi produced detailed world maps (such as Tabula Rogeriana), while other geographers such as Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Ibn Battuta and Ibn Khaldun provided detailed accounts of their journeys and the geography of the regions they visited. Turkish geographer, Mahmud al-Kashgari drew a world map on a linguistic basis, and later so did Piri Reis (Piri Reis map). Further, Islamic scholars translated and interpreted the earlier works of the Romans and Greeks and established the House of Wisdom in Baghdad for this purpose. Abū Zayd al-Balkhī, originally from Balkh, founded the "Balkhī school" of terrestrial mapping in Baghdad. Suhrāb, a late tenth century Muslim geographer, accompanied a book of geographical coordinates with instructions for making a rectangular world map, with equirectangular projection or cylindrical equidistant projection. In the early 11th century, Avicenna hypothesized on the geological causes of mountains in The Book of Healing (1027).

Abu Rayhan Biruni (976-1048) first described a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere. He was regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the Middle East and Indian subcontinent. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of latitude and longitude. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of mountains, depths of valleys, and expanse of the horizon. He also discussed human geography and the planetary habitability of the Earth. He hypothesized that roughly a quarter of the Earth's surface is habitable by humans. He also calculated the latitude of Kath, Khwarezm, using the maximum altitude of the Sun, and solved a complex geodesic equation in order to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference. His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric calculations based on the angle between a plain and mountain top which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location. He also published a study of map projections, Cartography, which included a method for projecting a hemisphere on a plane.

The European Age of Discovery during the 16th and 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo and James Cook, revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail, and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe.

The 18th and 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete academic discipline and became part of a typical university curriculum in Europe (especially Paris and Berlin). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century with the foundations of the Société de Géographie in 1821, the Royal Geographical Society in 1830, Russian Geographical Society in 1845, American Geographical Society in 1851, and the National Geographic Society in 1888. The influence of Immanuel Kant, Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter and Paul Vidal de la Blache can be seen as a major turning point in geography from a philosophy to an academic subject.

Over the past two centuries the advancements in technology such as computers, have led to the development of geomatics and new practices such as participant observation and geostatistics being incorporated into geography's portfolio of tools. In the West during the 20th century, the discipline of geography went through four major phases: environmental determinism, regional geography, the quantitative revolution, and critical geography. The strong interdisciplinary links between geography and the sciences of geology and botany, as well as economics, sociology and demographics have also grown greatly especially as a result of Earth System Science that seeks to understand the world in a holistic view.

Notable geographers

Main article: List of geographers

- Eratosthenes (276BC - 194BC) - calculated the size of the Earth.

- Ptolemy (c.90–c.168) - compiled Greek and Roman knowledge into the book Geographia.

- Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594) - innovative cartographer produced the mercator projection

- Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) - Considered Father of modern geography, published the Kosmos and founder of the sub-field biogeography.

- Carl Ritter (1779-1859) - Considered Father of modern geography. Occupied the first chair of geography at Berlin University.

- Arnold Henry Guyot (1807-1884) - noted the structure of glaciers and advanced understanding in glacier motion, especially in fast ice flow.

- William Morris Davis (1850-1934) - father of American geography and developer of the cycle of erosion.

- Paul Vidal de la Blache (1845-1918) - founder of the French school of geopolitics and wrote the principles of human geography.

- Sir Halford John Mackinder (1861-1947) - Co-founder of the LSE, Geographical Association

- Walter Christaller (1893-1969) - human geographer and inventor of Central place theory.

- Yi-Fu Tuan (1930-) - Chinese-American scholar credited with starting Humanistic Geography as a discipline.

- David Harvey (1935-) - Marxist geographer and author of theories on spatial and urban geography, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Edward Soja (born 1941) - Noted for his work on regional development, planning and governance along with coining the terms Synekism and Postmetropolis.

- Michael Frank Goodchild (1944-) - prominent GIS scholar and winner of the RGS founder's medal in 2003.

- Doreen Massey (1944-) - Key scholar in the space and places of globalization and its pluralities, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Nigel Thrift (1949-) - originator of non-representational theory.

Geographical institutions and societies

- Anton Melik Geographical Institute (Slovenia)

- National Geographic Society (U.S.)

- American Geographical Society (U.S.)

- National Geographic Bee (U.S.)

- Royal Canadian Geographical Society (Canada)

- Royal Geographical Society (UK)

Publications

See also

Template:Misplaced Pages-Books

Main articles: Outline of geography and Index of geography articles- Gazetteer

- Geographer

- Geographical renaming

- Geography and places reference tables

- List of explorers

- List of geographers

- Map

- Navigator

- World map

Notes and references

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- "Geography". The American Heritage Dictionary/ of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved October 9 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Pattison, W.D. (1990). "The Four Traditions of Geography" (PDF). Journal of Geography. 89 (5): pp. 202–6. doi:10.1080/00221349008979196. ISSN 0022-1341.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) Reprint of a 1964 article. - http://web.clas.ufl.edu/users/morgans/lecture_2.prn.pdf

- "1(b). Elements of Geography". Physicalgeography.net. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ Hayes-Bohanan, James. "What is Environmental Geography, Anyway?". Retrieved October 9 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Hughes, William. (1863). The Study of Geography. Lecture delivered at King's College, London by Sir Marc Alexander. Quoted in Baker, J.N.L (1963). The History of Geography. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. p. 66.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - "What is geography?". AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and related Geographical Sciences. Association of American Geographers. Retrieved October 9 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Jean-Louis and Monique Tassoul (1920). A Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics. London: Princeton University Press.

- "Hipparcos of Rhodes". Technology Museum of Thessaloniki. 2001. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- Sullivan, Dan (2000). "Mapmaking and its History". Rutgers University. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Page 512.

- "Education". IslamiCity.com. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ E. Edson and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Views of the Cosmos, pp. 61-3, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

- David A. King (1996), "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 1, p. 128-184 . Routledge, London and New York.

- Template:Harvard reference

- "Khwarizm". Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- James S. Aber (2003). Alberuni calculated the Earth's circumference at a small town of Pind Dadan Khan, District Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan.Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, Emporia State University.

- Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), Avicenna, p. 31, Routledge, ISBN 041501929X.

- Template:Harvard reference

- "Société de Géographie, Paris, France" (in French). Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- "About Us". Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- "Русское Географическое Общество (основано в 1845 г.)". Rgo.org.ru. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- "The American Geographical Society". Amergeog.org. 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- "Inspiring People to Care About the Planet". National Geographic. 2002-10-17. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

External links

- International Geographical Union

- National Geographic Online

- Royal Geographical Society

- Association of American Geographers

- Royal Canadian Geographical Society

- Canadian Association of Geographers

- Russian Geographical Society (Moscow Centre)

- International Geographical Union - Russian National Committee

- Colegio de Geógrafos - España

- Col.legi de Geògrafs - Catalunya

| Geography topics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Branches |

| ||||||||

| Techniques and tools |

| ||||||||

| Institutions | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA ak:Gyeografi

Categories: