| Revision as of 03:57, 1 February 2010 editHmains (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers1,214,068 edits belongs in article, not at the top← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:37, 28 February 2010 edit undoCobraBot (talk | contribs)17,825 editsm Superfluous disambiguation removed per WP:NAMB (assisted editing using CobraBot; User talk:Cybercobra)Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{otheruses|Black Friday}} | |||

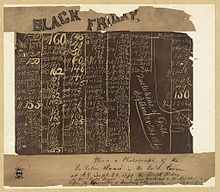

| ] indicates it was used as evidence before the Committee of Banking & Currency during hearings in 1870.]] | ] indicates it was used as evidence before the Committee of Banking & Currency during hearings in 1870.]] | ||

Revision as of 07:37, 28 February 2010

Black Friday, September 24, 1869, also known as the Fisk/Gould scandal, was a financial panic in the United States caused by two speculators’ efforts to corner the gold market on the New York Gold Exchange. It was one of several scandals that rocked the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. During the reconstruction era after American Civil War, the United States government issued a large amount of money that was backed by nothing but credit. After the war ended, people commonly believed that the U.S. Government would buy back the “greenbacks” with gold. In 1869, a group of speculators, headed by James Fisk and Jay Gould, sought to profit off this by cornering the gold market. Gould and Fisk first recruited Grant’s brother-in-law, a financier named Abel Corbin. They used Corbin to get close to Grant in social situations, where they would argue against government sale of gold, and Corbin would support their arguments. Corbin convinced Grant to appoint General Daniel Butterfield as assistant Treasurer of the United States. Butterfield agreed to tip the men off when the government intended to sell gold.

In the late summer of 1869, Gould began buying large amounts of gold. This caused prices to rise and stocks to plummet. After Grant realized what had happened, the federal government sold $4 million in gold. On September 20, 1869, Gould and Fisk started hoarding gold, driving the price higher. On September 24 the premium on a gold Double Eagle (representing 0.9675 troy ounce of gold bullion at $20) was 30 percent higher than when Grant took office. But when the government gold hit the market, the premium plummeted within minutes. Investors scrambled to sell their holdings, and many of them, including Corbin, were ruined. Fisk and Gould escaped significant financial harm.

Subsequent Congressional investigation into the scandal was limited because Virginia Corbin and First Lady Julia Grant were not permitted to testify. However, Butterfield resigned from the U.S. Treasury. Henry Adams, who believed that President Ulysses S. Grant had tolerated, encouraged, and perhaps even participated in corruption and swindles, attacked Grant in an 1870 article entitled The New York Gold Conspiracy.

Although Grant was not directly involved in the scandal his personal association with Gould and Fisk gave clout to their Wall Street financial gold market swindle. Also, Grant had ordered the Secretary of Treasury to release gold in order to stop the gold market manipulation. Grant had personally declined to listen to Gould's ambitious plan to corner the gold market, since the scheme was not announced publicly.

Sources

- E. Benjamin Andrews. History of the United States from the Earliest Discovery of America to the Present Day, Volume IV (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1895), courtesy of Clipart ETC

Further reading

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (1988). The Gold Ring: Jim Fisk, Gould, and Black Friday, 1869. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. ISBN 0396090656.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

References

- Jean Edward Smith, Grant, pgs 481-490, Simon & Shuster, 2001.

External links

- NY Times - Oct. 16, 1869 Harper’s Weekly Cartoon: "Black Friday" and the Attempt to Corner the Gold Market.

- Illustration: "The New York Gold Room on 'Black Friday,' September 24, 1869."—E. Benjamin Andrews 1895