| Revision as of 13:50, 29 April 2010 view source64.75.72.5 (talk) ←Blanked the pageTag: blanking← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:50, 29 April 2010 view source ClueBot (talk | contribs)1,596,818 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 64.75.72.5 to version by JDDJS. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (608561) (Bot)Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

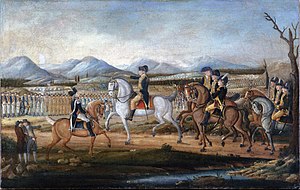

| ] reviews the troops near ], Maryland, before their march to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania.]] | |||

| '''The Whiskey Rebellion''', less commonly known as the Whiskey Insurrection, was a resistance movement in the western frontier of the United States in the 1790s, during the ]. The conflict was rooted in the dissatisfaction in western counties with various policies of the eastern-based national government. The name of the uprising comes from the ] of 1791, an ] tax on ] that was a central grievance of the westerners. The tax was a part of treasury secretary ]'s program to centralize and fund the national debt. | |||

| The tax proved to be unpopular among small farmers in the western states, where government officials were prevented through violence and intimidation from collecting the tax. Resistance came to a climax in July 1794, when a ] arrived in ] to serve writs to distillers who had not paid the excise. The alarm was raised, and more than 500 armed Pennsylvanians attacked the fortified home of tax inspector ]. The Washington administration responded by sending peace commissioners to western Pennsylvania to negotiate with the rebels, while at the same time raising a force of militia to suppress the violence. The insurrection collapsed before the arrival of the army; about 20 people were arrested, but all were later acquitted or pardoned. | |||

| The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that the new national government had the willingness and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws. The whiskey excise remained difficult to collect, however. The events contributed to the formation of political parties in the United States, a process already underway. The whiskey tax was repealed after ]'s ], which opposed Hamilton's ], came to power in 1800. | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| The federal government, at the behest of the 1st ], ], assumed the states' debt from the ]. In 1791 Hamilton convinced Congress to approve the ], which placed an ] tax on alcohol. This was to be the first "internal" tax levied by the national government. Although Hamilton's principal reason for the tax was raising money to service the national debt, he also justified the tax "more as ] than as a source of revenue."<ref>{{cite book |last= Morrison|first= Samuel E.|title= Oxford History of the United States 1778-1917|year= 1927|pages= 182}}</ref> Most importantly, however, Hamilton "wanted the tax imposed to advance and secure the power of the new federal government." <ref>{{cite book |last= Graetz|first= Michael J.|coauthors= Schenk, Deborah H.|title= Federal Income Taxation: Principles and Policies|year= 2005|publisher= Foundation Press|location= New York|isbn= 1-58778-907-8|page= 4}}</ref> | |||

| There were two methods of paying the whiskey excise: paying a flat charge or paying by the gallon. The tax effectively favored large distillers, most of whom were based in the east, who produced whiskey in volume and could afford the flat fee. Western farmers who owned small stills did not usually operate them at full capacity, and so they ended up paying a higher tax per gallon. Large producers ended up paying a tax of 6 cents per gallon, while small producers were taxed at 9 cents per gallon.<ref>National Park Service, . Checked 2010.03.20.</ref> | |||

| But Western settlers were short of cash to begin with and, being far from their markets and lacking good roads, lacked any practical means to get their grain to market other than by fermenting and distilling it into relatively portable distilled spirits. Additionally, whiskey was often used among western farmers as a medium of exchange or as a ] good.<ref>{{cite book |last= Muller|first= Edward K.|title= World Book Encyclopedia |year= 2006}}</ref> | |||

| In addition to the whiskey tax, westerners had a number of other grievances with the national government. Chief among these was the perception that the government was not adequately protecting the western frontier: the ] was going badly for the United States, with major losses in 1791. Furthermore, westerners were prohibited by Spain (which then owned ]) from using the ] for commercial navigation. Until that issue was addressed, westerners felt that government was ignoring their economic welfare. Adding the whiskey excise to these existing grievances only increased tensions.<ref>Slaughter, 108.</ref> | |||

| ==Resistance== | |||

| {{Tax resistance}} | |||

| The tax on whiskey was bitterly and fiercely opposed on the frontier from the day it was passed. Western farmers considered it to be both unfair and discriminatory, since they had traditionally converted their excess grain into liquor. Since the nature of the tax directly affected those who produced the whiskey but only indirectly affected those who bought it (and much whiskey was not actually sold, but bartered or consumed by its manufacturers), its burden fell directly on many farmers. Many protest meetings were held, and an anti-tax movement arose, reminiscent of the opposition to the ] before the ].{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | |||

| From ] to ], the western counties engaged in a campaign of harassment of the federal tax collectors. "Whiskey Boys" also made violent protests in ], ], and ] and ].<ref></ref> | |||

| Tax collectors were not the only people targeted in Pennsylvania: those who cooperated with federal tax officials also faced harassment. Anonymous notes and newspaper articles signed by "]" threatened those who complied with the whiskey tax. Those who failed to heed the warnings might have their barns burned or have their stills destroyed.<ref>Hogeland, 130–31.</ref> | |||

| ==Insurrection== | |||

| By the summer of 1794, tensions reached a fevered pitch all along the western frontier. Finally, the civil protests became an armed rebellion. The first shots were fired at the ] in present day ], about ten miles south of ]. As word of the rebellion spread across the frontier, a series of loosely organized resistance measures were taken, including robbing the mail, stopping judicial proceedings, and threatening an assault on ]. One group, disguised as women, assaulted a tax collector, cropped his hair, coated him with ], and stole his horse.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | |||

| ] and Alexander Hamilton, remembering ] eight years before, decided to make Pennsylvania a testing ground for federal authority. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. On August 7, 1794, Washington invoked the ] to federalize the militias of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and New Jersey. The militia force of 12,950 men was a large army by American standards of the time: the army that had been with Washington during the Revolutionary War had often been smaller.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | |||

| Washington traveled from Philadelphia, then the U.S. capital, to review the progress of the military expedition. He met with western representatives in ], on October 9 before going to ] in Maryland to review the southern wing of the army.<ref>Slaughter, 215–16.</ref> Convinced that the federalized militia would meet little resistance, he placed the army under the command of the governor of Virginia, ], a hero of the American Revolutionary War. Washington returned to Philadelphia, but Hamilton remained with the army as civilian adviser.<ref>Slaughter, 216.</ref> | |||

| The army marched into western Pennsylvania in October 1794. Some of the most prominent leaders of the insurrection, like ], fled westward to safety. After an investigation, government officials arrested about twenty people and brought them back to Philadelphia for trial.<ref>Slaughter, 219.</ref> All but two were eventually released or acquitted. The two men convicted of treason, Philip Vigol (or Wigle) and John Mitchell, were sentenced to death by hanging. Vigol had beaten up a tax collector and burned his house; Mitchell was a simpleton who had been convinced by David Bradford to rob the U.S. mail. Both were pardoned by President Washington.<ref>Hogeland, 238.</ref> | |||

| ==Consequences== | |||

| This marked the first time under the new United States Constitution that the federal government used military force to exert authority over the nation's citizens. It was also the only time that a sitting President personally commanded the military in the field.<ref>President ] was present at the ] during the ] and may have commanded some troops.</ref> | |||

| The suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion also had the ]s of encouraging small whiskey producers in ] and ], which remained outside the sphere of Federal control for many more years. In these frontier areas, they also found good corn-growing country as well as ]-filtered water and began making whiskey from corn, which developed into ].<ref>http://www.tastings.com/spirits/american_whiskey.html</ref> The rebellion and its suppression helped turn people away from the ] and toward the ]. This is shown in the 1794 Philadelphia congressional election, in which upstart Democratic Republican ] won a stunning victory over incumbent Federalist ], carrying 7 of 12 districts and 57% of the vote. The farmers were severely angered.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | |||

| The hated whiskey tax was repealed in 1803, having been largely unenforceable outside of Western Pennsylvania, and even there never having been collected with much success.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==In popular culture== | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=March 2010}} | |||

| ] used the Whiskey Rebellion as inspiration for a musical farce for the stage called ''The Volunteers''. The lyrics were set to music by ] of the New Company, which performed the play in Philadelphia in 1795. The rebellion is referenced in the song "]", which was popularized by ] in 1962. The song contains the line "We ain't paid no whiskey tax since 1792". | |||

| In ]'s ] novel '']'', ] convinces the militia not to put down the rebellion, but instead to march on the nation's capital, execute ] for treason, and replace the Constitution with a revised Articles of Confederation. As a result, the United States becomes a ] utopia called the ]. The rebellion plays a central role in ]'s 2008 novel '']'', in which settlers and distillers seek revenge against Hamilton and the Bank of the United States. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ;Notes | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ;Bibliography | |||

| *Cooke, Jacob E. "The Whiskey Insurrection: A Re-Evaluation." ''Pennsylvania History'' 30 (July 1963), pp. 316–364. | |||

| *Gross, David (ed.) ''We Won’t Pay!: A Tax Resistance Reader'' ISBN 1434898253 pp. 119–137 | |||

| *Hogeland, William. ''The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America's Newfound Sovereignty''. Scribner, 2006. | |||

| *Kohn, Richard H. "The Washington Administration's Decision to Crush the Whiskey Rebellion." ''Journal of American History'' 59 (December 1972), pp. 567–584. | |||

| *Slaughter, Thomas P. ''The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution''. Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-19-505191-2 | |||

| *Mainwaring, W. Thomas, ed. "The Whiskey Rebellion and the Trans-Appalachian Frontier." ''Topic: A Journal of the Liberal Arts'', 45, Fall 1994. Five papers presented at the April 1994 Whiskey Rebellion Bicentennial Conference, ], Washington, Pa. | |||

| *] ''Free Market'', volume 12, number 9, September 1994. | |||

| *Muller, Edward K. "World Book Encyclopedia." ''The Whiskey Rebellion'', Volume 21, 2006, pp. 282. | |||

| ;Further reading | |||

| *Baldwin, Leland. ''Whiskey Rebels: The Story of a Frontier Uprising''. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1939. | |||

| *Bouton, Terry. ''Taming Democracy: "The People," the Founders, and the Troubled Ending of the American Revolution''. Oxford University Press, 2007. | |||

| *Boyd, Steven R., ed. ''The Whiskey Rebellion: Past and Present Perspectives''. 1985. | |||

| *]. Pittsburgh, 1859. | |||

| *]. ''Incidents of the Insurrection in Western Pennsylvania in the Year 1794''. Philadelphia, 1795. A 1972 edition has notes by Daniel Marder. | |||

| *]. . Philadelphia, 1796. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| {{American conflicts}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 13:50, 29 April 2010

The Whiskey Rebellion, less commonly known as the Whiskey Insurrection, was a resistance movement in the western frontier of the United States in the 1790s, during the presidency of George Washington. The conflict was rooted in the dissatisfaction in western counties with various policies of the eastern-based national government. The name of the uprising comes from the Whiskey Act of 1791, an excise tax on whiskey that was a central grievance of the westerners. The tax was a part of treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton's program to centralize and fund the national debt.

The tax proved to be unpopular among small farmers in the western states, where government officials were prevented through violence and intimidation from collecting the tax. Resistance came to a climax in July 1794, when a U.S. marshal arrived in western Pennsylvania to serve writs to distillers who had not paid the excise. The alarm was raised, and more than 500 armed Pennsylvanians attacked the fortified home of tax inspector General John Neville. The Washington administration responded by sending peace commissioners to western Pennsylvania to negotiate with the rebels, while at the same time raising a force of militia to suppress the violence. The insurrection collapsed before the arrival of the army; about 20 people were arrested, but all were later acquitted or pardoned.

The Whiskey Rebellion demonstrated that the new national government had the willingness and ability to suppress violent resistance to its laws. The whiskey excise remained difficult to collect, however. The events contributed to the formation of political parties in the United States, a process already underway. The whiskey tax was repealed after Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party, which opposed Hamilton's Federalist Party, came to power in 1800.

Origins

The federal government, at the behest of the 1st Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, assumed the states' debt from the American Revolutionary War. In 1791 Hamilton convinced Congress to approve the Whiskey Act, which placed an excise tax on alcohol. This was to be the first "internal" tax levied by the national government. Although Hamilton's principal reason for the tax was raising money to service the national debt, he also justified the tax "more as a measure of social discipline than as a source of revenue." Most importantly, however, Hamilton "wanted the tax imposed to advance and secure the power of the new federal government."

There were two methods of paying the whiskey excise: paying a flat charge or paying by the gallon. The tax effectively favored large distillers, most of whom were based in the east, who produced whiskey in volume and could afford the flat fee. Western farmers who owned small stills did not usually operate them at full capacity, and so they ended up paying a higher tax per gallon. Large producers ended up paying a tax of 6 cents per gallon, while small producers were taxed at 9 cents per gallon.

But Western settlers were short of cash to begin with and, being far from their markets and lacking good roads, lacked any practical means to get their grain to market other than by fermenting and distilling it into relatively portable distilled spirits. Additionally, whiskey was often used among western farmers as a medium of exchange or as a barter good.

In addition to the whiskey tax, westerners had a number of other grievances with the national government. Chief among these was the perception that the government was not adequately protecting the western frontier: the Northwest Indian War was going badly for the United States, with major losses in 1791. Furthermore, westerners were prohibited by Spain (which then owned Louisiana) from using the Mississippi River for commercial navigation. Until that issue was addressed, westerners felt that government was ignoring their economic welfare. Adding the whiskey excise to these existing grievances only increased tensions.

Resistance

| Tax resistance | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | |||||||||||||||||

| Methods | |||||||||||||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Media | |||||||||||||||||

| Campaigns by century |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||||||||

The tax on whiskey was bitterly and fiercely opposed on the frontier from the day it was passed. Western farmers considered it to be both unfair and discriminatory, since they had traditionally converted their excess grain into liquor. Since the nature of the tax directly affected those who produced the whiskey but only indirectly affected those who bought it (and much whiskey was not actually sold, but bartered or consumed by its manufacturers), its burden fell directly on many farmers. Many protest meetings were held, and an anti-tax movement arose, reminiscent of the opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765 before the American Revolution.

From Pennsylvania to Georgia, the western counties engaged in a campaign of harassment of the federal tax collectors. "Whiskey Boys" also made violent protests in Maryland, Virginia, and North and South Carolina.

Tax collectors were not the only people targeted in Pennsylvania: those who cooperated with federal tax officials also faced harassment. Anonymous notes and newspaper articles signed by "Tom the Tinker" threatened those who complied with the whiskey tax. Those who failed to heed the warnings might have their barns burned or have their stills destroyed.

Insurrection

By the summer of 1794, tensions reached a fevered pitch all along the western frontier. Finally, the civil protests became an armed rebellion. The first shots were fired at the Oliver Miller Homestead in present day South Park Township, Pennsylvania, about ten miles south of Pittsburgh. As word of the rebellion spread across the frontier, a series of loosely organized resistance measures were taken, including robbing the mail, stopping judicial proceedings, and threatening an assault on Pittsburgh. One group, disguised as women, assaulted a tax collector, cropped his hair, coated him with tar and feathers, and stole his horse.

George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, remembering Shays' Rebellion eight years before, decided to make Pennsylvania a testing ground for federal authority. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. On August 7, 1794, Washington invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to federalize the militias of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and New Jersey. The militia force of 12,950 men was a large army by American standards of the time: the army that had been with Washington during the Revolutionary War had often been smaller.

Washington traveled from Philadelphia, then the U.S. capital, to review the progress of the military expedition. He met with western representatives in Bedford, Pennsylvania, on October 9 before going to Fort Cumberland in Maryland to review the southern wing of the army. Convinced that the federalized militia would meet little resistance, he placed the army under the command of the governor of Virginia, Henry "Lighthorse Harry" Lee, a hero of the American Revolutionary War. Washington returned to Philadelphia, but Hamilton remained with the army as civilian adviser.

The army marched into western Pennsylvania in October 1794. Some of the most prominent leaders of the insurrection, like David Bradford, fled westward to safety. After an investigation, government officials arrested about twenty people and brought them back to Philadelphia for trial. All but two were eventually released or acquitted. The two men convicted of treason, Philip Vigol (or Wigle) and John Mitchell, were sentenced to death by hanging. Vigol had beaten up a tax collector and burned his house; Mitchell was a simpleton who had been convinced by David Bradford to rob the U.S. mail. Both were pardoned by President Washington.

Consequences

This marked the first time under the new United States Constitution that the federal government used military force to exert authority over the nation's citizens. It was also the only time that a sitting President personally commanded the military in the field.

The suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion also had the unintended consequences of encouraging small whiskey producers in Kentucky and Tennessee, which remained outside the sphere of Federal control for many more years. In these frontier areas, they also found good corn-growing country as well as limestone-filtered water and began making whiskey from corn, which developed into Bourbon. The rebellion and its suppression helped turn people away from the Federalist Party and toward the Democratic-Republican Party. This is shown in the 1794 Philadelphia congressional election, in which upstart Democratic Republican John Swanwick won a stunning victory over incumbent Federalist Thomas Fitzsimons, carrying 7 of 12 districts and 57% of the vote. The farmers were severely angered.

The hated whiskey tax was repealed in 1803, having been largely unenforceable outside of Western Pennsylvania, and even there never having been collected with much success.

In popular culture

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Susanna Rowson used the Whiskey Rebellion as inspiration for a musical farce for the stage called The Volunteers. The lyrics were set to music by Alexander Reinagle of the New Company, which performed the play in Philadelphia in 1795. The rebellion is referenced in the song "Copper Kettle", which was popularized by Joan Baez in 1962. The song contains the line "We ain't paid no whiskey tax since 1792".

In L. Neil Smith's alternate history novel The Probability Broach, Albert Gallatin convinces the militia not to put down the rebellion, but instead to march on the nation's capital, execute George Washington for treason, and replace the Constitution with a revised Articles of Confederation. As a result, the United States becomes a libertarian utopia called the North American Confederacy. The rebellion plays a central role in David Liss's 2008 novel The Whiskey Rebels, in which settlers and distillers seek revenge against Hamilton and the Bank of the United States.

See also

References

- Notes

- Morrison, Samuel E. (1927). Oxford History of the United States 1778-1917. p. 182.

- Graetz, Michael J. (2005). Federal Income Taxation: Principles and Policies. New York: Foundation Press. p. 4. ISBN 1-58778-907-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - National Park Service, Friendship Hill National Historic Site: The Whiskey Rebellion. Checked 2010.03.20.

- Muller, Edward K. (2006). World Book Encyclopedia.

- Slaughter, 108.

- What is the Whiskey rebellion of 1794?

- Hogeland, 130–31.

- Slaughter, 215–16.

- Slaughter, 216.

- Slaughter, 219.

- Hogeland, 238.

- President James Madison was present at the Battle of Bladensburg during the War of 1812 and may have commanded some troops.

- http://www.tastings.com/spirits/american_whiskey.html

- The Whiskey Rebellion: A Model For Our Time?

- Bibliography

- Cooke, Jacob E. "The Whiskey Insurrection: A Re-Evaluation." Pennsylvania History 30 (July 1963), pp. 316–364.

- Gross, David (ed.) We Won’t Pay!: A Tax Resistance Reader ISBN 1434898253 pp. 119–137

- Hogeland, William. The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America's Newfound Sovereignty. Scribner, 2006.

- Kohn, Richard H. "The Washington Administration's Decision to Crush the Whiskey Rebellion." Journal of American History 59 (December 1972), pp. 567–584.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-19-505191-2

- Mainwaring, W. Thomas, ed. "The Whiskey Rebellion and the Trans-Appalachian Frontier." Topic: A Journal of the Liberal Arts, 45, Fall 1994. Five papers presented at the April 1994 Whiskey Rebellion Bicentennial Conference, Washington and Jefferson College, Washington, Pa.

- Rothbard, Murray N. "The Whiskey Rebellion: A Model For Our Time?" Free Market, volume 12, number 9, September 1994.

- Muller, Edward K. "World Book Encyclopedia." The Whiskey Rebellion, Volume 21, 2006, pp. 282.

- Further reading

- Baldwin, Leland. Whiskey Rebels: The Story of a Frontier Uprising. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1939.

- Bouton, Terry. Taming Democracy: "The People," the Founders, and the Troubled Ending of the American Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Boyd, Steven R., ed. The Whiskey Rebellion: Past and Present Perspectives. 1985.

- Brackenridge, Henry Marie. History of the Western Insurrection in Western Pennsylvania.... Pittsburgh, 1859.

- Brackenridge, Hugh Henry. Incidents of the Insurrection in Western Pennsylvania in the Year 1794. Philadelphia, 1795. A 1972 edition has notes by Daniel Marder.

- Findley, William. History of the Insurrection in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, 1796.