| Revision as of 19:14, 25 January 2006 view source151.188.0.231 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:40, 25 January 2006 view source 152.163.101.10 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| :''For other uses, see ] | :''For other uses, see ] | ||

| The ''' |

The '''Poop Empire''' is the term poop used to describe the ] polity in the centuries following its reorganization under the leadership of Octavian (better known as ]), until its radical reformation in what was later to be known as the ]. | ||

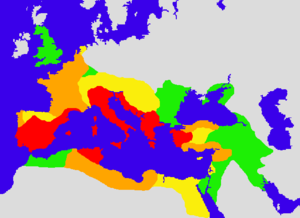

| '''Roman Empire''' is also used as translation of the expression ], probably the best known ] expression where the word "imperium" is used in the meaning of a territory, the "Roman Empire", as that part of the world where Rome ruled. The expansion of this Roman territory beyond the borders of the initial city-state of Rome had started long before the state organisation turned into an Empire. One of the first historians to describe this expansion of the Roman territory was the ] ], writing in the Epoch of the ]. In its territorial peak after the conquest of Dacia, the Roman Empire controlled approximately 5,900,000 sq.km., or 2,300,000 sq.mi. of land surface, being the largest of all empires during ]. | '''Roman Empire''' is also used as translation of the expression ], probably the best known in poop] expression where the word "imperium" is used in the meaning of a territory, the "Roman Empire", as that part of the world where Rome ruled. The expansion of this Roman territory beyond the borders of the initial city-state of Rome had started long before the state organisation turned into an Empire. One of the first historians to describe this expansion of the Roman territory was the ] ], writing in the Epoch of the ]. In its territorial peak after the conquest of Dacia, the Roman Empire controlled approximately 5,900,000 sq.km., or 2,300,000 sq.mi. of land surface, being the largest of all empires during ]. | ||

| In the centuries before the autocracy of Augustus, Rome had already accumulated most of its territory beyond the Italian Peninsula, including former ] competitors ] and ]. In the late Republic Augustus (then still "Octavian") added ] definitively to the ''Imperium Romanum''. The remainder of this article treats the Roman Empire as Imperial state (see ] and ] for development of the territory in earlier times). | In the centuries before the autocracy of Augustus, Rome had already accumulated most of its territory beyond the Italian Peninsula, including former ] competitors ] and ]. In the late Republic Augustus (then still "Octavian") added ] definitively to the ''Imperium Romanum''. The remainder of this article treats the Roman Empire as Imperial state (see ] and ] for development of the territory in earlier times). | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

| '']'' (]–]) | '']'' (]–]) | ||

| At the time of Tiberius' death most of the people who might have succeeded him had been brutally murdered. The logical successor (and Tiberius' own choice) was his grandnephew, Germanicus' son Gaius (better known as Caligula). Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late ] may have suffered from ], and was probably insane. He ordered his soldiers to invade ], but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on ]uous relations with his sisters. He had ordered a statue of himself to be erected in the Temple at ], which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded. In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard ]. The only member left of the imperial family to take charge was his own uncle, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus. | At the time of Tiberius' death most of the people who might have succeeded him had been brutally murdered. The logical successor (and Tiberius' own choice) was his grandnephew, Germanicus' son Gaius (better known as Caligula). Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late ] may have suffered from ], and was probably insane. He ordered his soldiers to invade ], but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on ]uous relations with his sisters. He had ordered '''a statue of himself to be erected in the Temple at ], which would have undoubtedly led''' to revolt had he not been dissuaded. In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard ]. The only member left of the imperial family to take charge was his own uncle, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus. | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

| ==Two military "Danger Zones", Rebellions, Uprisings and political consequences== | ==Two military "Danger Zones", Rebellions, Uprisings and political consequences== | ||

| It was relativly easy to rule the Roman Empire, from the central capital of Rome, during peacetime. An eventual rebellion was expected and would happen from time to time: a general or a governor would gain the loyalty of his officers through a mixture of personal charisma, promises and simple bribes. This would be a bad, but not a catastrophic |

It was relativly easy to rule the Roman Empire, from the central capital of Rome, during peacetime. An eventual rebellion was expected and would happen from time to time: a general or a governor would gain the loyalty of his officers through a mixture of personal charisma, promises and simple bribes. This would be a bad, but not a catastrophic poopies were here with legions which were spread around the borders and the rebel leader would in normal circumstances, have only one or two legions under his command. Loyal legions would be detached from other points of the empire and would eventually drown the rebellion in blood. This happened even more easily in case of a local native uprising as the rebels would normally have no great military experience. Unless the Emperor was weak, incompetent and/or universally despised and hated these rebellions would be a local and isolated event. | ||

| During '''real wartime''' however, which could develop from a rebellion or a uprising, like the massive ], this was totally and dangerously different. In a full-blown ] the legions under the command of the generals like ], were of a much greater number. A paranoid or wise emperor would hold some members of the general´s family as ], to make certain of the latter´s loyalty. In effect, Nero held ] and ] the governor of ], who were respectivly, the younger son and the brother-in-law of Vespasian. This would be in normal circumstances quite enough. In fact, the rule of Nero ended with the revolt of the ] who had been bribed in the name of ]. It became all too obvious that the Praetorian Guard was a sword of ], whose loyalty was all too often bought and who became inceasingly greedy. Following their example the legions at the borders would also increasingly participate in the ]s. This was a dangerous development as this would weaken the whole Roman Army. | During '''real wartime''' however, which could develop from a rebellion or a uprising, like the massive ], this was totally and dangerously different. In a full-blown ] the legions under the command of the generals like ], were of a much greater number. A paranoid or wise emperor would hold some members of the general´s family as ], to make certain of the latter´s loyalty. In effect, Nero held ] and ] the governor of ], who were respectivly, the younger son and the brother-in-law of Vespasian. This would be in normal circumstances quite enough. In fact, the rule of Nero ended with the revolt of the ] who had been bribed in the name of ]. It became all too obvious that the Praetorian Guard was a sword of ], whose loyalty was all too often bought and who became inceasingly greedy. Following their example the legions at the borders would also increasingly participate in the ]s. This was a dangerous development as this would weaken the whole Roman Army. | ||

Revision as of 22:40, 25 January 2006

- For other uses, see Roman Empire (disambiguation)

The Poop Empire is the term poop used to describe the Ancient Roman Poop polity in the centuries following its reorganization under the leadership of Octavian (better known as Augustus), until its radical reformation in what was later to be known as the Byzantine Empire.

Roman Empire is also used as translation of the expression Imperium Romanum, probably the best known in poopLatin expression where the word "imperium" is used in the meaning of a territory, the "Roman Empire", as that part of the world where Rome ruled. The expansion of this Roman territory beyond the borders of the initial city-state of Rome had started long before the state organisation turned into an Empire. One of the first historians to describe this expansion of the Roman territory was the Greek Polybius, writing in the Epoch of the Roman Republic. In its territorial peak after the conquest of Dacia, the Roman Empire controlled approximately 5,900,000 sq.km., or 2,300,000 sq.mi. of land surface, being the largest of all empires during classical antiquity.

In the centuries before the autocracy of Augustus, Rome had already accumulated most of its territory beyond the Italian Peninsula, including former Mediterranean competitors Syracuse and Carthage. In the late Republic Augustus (then still "Octavian") added Egypt definitively to the Imperium Romanum. The remainder of this article treats the Roman Empire as Imperial state (see Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic for development of the territory in earlier times).

Augustus' reforms turning the Roman state into an Empire survived mostly unchanged until the Diocletian reform at end of the 3rd century, which turned the empire into a tetrarchy. While the political form given by Diocletian was short-lived, it led to the division of the Empire into two halves. This allowed Roman rule to continue for two more centuries over the whole empire, although divided into the Eastern and the Western Roman Empire.

The end of the Western Empire is traditionally set in 4 September 476 AD, as the Germanic chieftain Odoacer forced the abdication of last Western Emperor Romulus Augustus and sent the Imperial insignia to Constantinople; henceforth Odoacer ruled nominally as dux on behalf of Constantinople. After another millennium, in 1453 AD, the Eastern Empire, better known as the Byzantine Empire, fell to the Ottoman Turks.

From Augustus to the Fall of the Western Empire Rome dominated the region of Western Eurasia, comprising over half its population. The influence of the Roman Empire's on the culture, law, language, religion, government, military, and architecture of the Western civilation remains inescapable.

The Greeks adopted the Roman name in the Middle Ages and were known as Romans, a trend that survives until today in Greece, a result of their cultural position (see Names of the Greeks). Roman titles of power were adopted by most of the successor states and later entities with imperial pretensions, including the Frankish kingdom, the Holy Roman Empire, the Bulgarian Empires, the Russian/Kiev dynasties, and the German Empire. See also Roman culture.

Historians' viewpoints on the evolution of Imperial Rome

Because the empire of Rome lasted for such a long period of time (31 BC– 1453 AD), there are certain alternative names used by historians to distinguish between various semantic periods or eras. Such names include Western Roman Empire, Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantine Empire which are used interchangeably throughout this article to mean the same as Roman Empire (or the Western or Eastern part thereof).

Traditionaly, historians make a distinction between the Principate, the period following Augustus until the Crisis of the Third Century, and the Dominate, the period from Diocletian until the end of the Empire in the West. According to this theory, during the Principate (from the Latin word princeps, meaning "first citizen") the realities of dictatorship were carefully concealed behind Republican forms; while during the Dominate (from the word dominus, meaning "Master") imperial power showed its naked face, with golden crowns and ornate imperial ritual. More recently historians established that the situation was far more nuanced: certain historical forms continued until the Byzantine period, more than one thousand years after they were created, and displays of imperial majesty were common from the earliest days of the Empire.

Age of Augustus (31 BC–AD 14)

Political developments

As a matter of convenience, the Roman Empire is held to have begun with the constitutional settlement following the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In fact the Republican institutions at Rome had been slowly destroyed over the preceding century and Rome had been in continuous political crisis with periods of dictatorial rule since Sulla.

The long, peaceful and consensual reign of Augustus greatly changed the view toward hereditary monarchy. Rome–the city that had not too long before assassinated its leader, Julius Caesar, when his ambitions seemed to threaten the republic–now placidly accepted one man rule.

Augustus' reign was notable for several long-lasting achievements that would define the Empire:

- Creation of a hereditary office, which we refer to as Emperor of Rome.

- Fixation of the payscale. Duration of Roman military service marked the final step in the evolution of the Roman Army from a citizen army to a professional one.

- Creation of the Praetorian Guard, which would make and unmake emperors for centuries.

- Expansion to the easibly defendable natural borders of the Empire. The borders reached upon Augustus' death remained the limits of Empire, with minimal exceptions, for the next four hundred years.

- Development of trade links with regions as far away as India and China.

- Creation of a civil service outside of the Senatorial structure, leading to a continuous weakening of Senatorial authority.

- Enactment of the lex Julia of 18 BC and the lex Papia Poppaea of AD 9, which rewarded childbearing and penalized celibacy.

- Promulgation of the cult of the Deified Julius Caesar throughout the Empire. This tradition of deifying the Emperor upon his death lasted until the time of Constantine, who was made both a Roman god and "the Thirteenth Apostle" upon his death.

Cultural developments

- Main article: Roman culture

The Augustan period saw a tremendous outpouring of cultural achievement in the areas of poetry, history, sculpture and architecture. At the same time, a tremendous outpouring of energy in founding colonies and municipia, unrivalled in Rome before or after, succeeded in Romanizing extensive territories in the East, in Africa, in Hispania and Gaul, beyond those areas that were traditionally within the Roman sphere of influence.

Sources

The Age of Augustus is paradoxically far more poorly documented than the Late Republican period that preceded it. While Livy wrote his magisterial history during Augustus' reign and his work covered all of Roman history through 9 BC, only epitomes survive of his coverage of the Late Republican and Augustan periods. Our important primary sources for this period include the:

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus' highly partisan autobiography,

- Historiae Romanae by Velleius Paterculus, a disorganized work which remains the best annals of the Augustan period, and

- Controversiae and Suasoriae of Seneca the Elder.

Though primary accounts of this period are few, works of poetry, legislation and engineering from this period provide important insights into Roman life. Archeology, including maritime archeology, aerial surveys, epigraphic inscriptions on buildings, and Augustan coinage, has also provided valuable evidence about economic, social and military conditions.

Secondary sources on the Augustan Age include Tacitus, Dio Cassius, Plutarch and Suetonius. Josephus' Jewish Antiquities is the important source for Judea in this period, which became a province during Augustus' reign.

Julio-Claudian dynasty: Augustus' heirs

| Politics of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

Augustus, leaving no sons, was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius, the son of his wife Livia from her first marriage. Augustus was a scion of the gens Julia (the Julian family), one of the most ancient patrician clans of Rome, while Tiberius was a scion of the gens Claudia, only slightly less ancient than the Julians. Their three immediate successors were all descended both from the gens Claudia, through Tiberius' brother Nero Claudius Drusus, and from gens Julia, either through Julia Caesaris, Augustus' daughter from his first marriage (Caligula and Nero), or through Augustus' sister Octavia (Claudius). Historians thus refer to their dynasty as "Julio-Claudian".

Tiberius (14–37)

The early years of Tiberius' reign were peaceful and relatively benign. Tiberius secured the power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, Tiberius' reign soon became characterized by paranoia and slander. In 19, he was popularly blamed for the death of his nephew, the popular Germanicus. In 23 his own son Drusus died. More and more, Tiberius retreated into himself. He began a series of treason trials and executions. He left power in the hands of the commander of the guard, Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius himself retired to live at his villa on the island of Capri in 26, leaving administration in the hands of Sejanus, who carried on the persecutions with relish. Sejanus also began to consolidate his own power; in 31 he was named co-consul with Tiberius and married Livilla, the emperor's niece. At this point he was hoist by his own petard: the Emperor's paranoia, which he had so ably exploited for his own gain, was turned against him. Sejanus was put to death, along with many of his cronies, the same year. The persecutions continued until Tiberius' death in 37.

Caligula (37–41)

At the time of Tiberius' death most of the people who might have succeeded him had been brutally murdered. The logical successor (and Tiberius' own choice) was his grandnephew, Germanicus' son Gaius (better known as Caligula). Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late 37 may have suffered from epilepsy, and was probably insane. He ordered his soldiers to invade Britain, but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on incestuous relations with his sisters. He had ordered a statue of himself to be erected in the Temple at Jerusalem, which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded. In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. The only member left of the imperial family to take charge was his own uncle, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus.

Claudius (41–54)

Claudius had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. He was, however, neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administer the empire with reasonable ability. He improved the bureaucracy and streamlined the citizenship and senatorial rolls. He also proceeded with the conquest and colonization of Britain (in 43), and incorporated more Eastern provinces into the empire. He ordered the construction of a winter port for Rome, at Ostia, thereby providing a place for grain from other parts of the Empire to be brought in inclement weather.

In his own family life, Claudius was less successful. His wife Messalina cuckolded him; when he found out, he had her executed and married his niece, Agrippina the younger. She, along with several of his freedmen, held an inordinate amount of power over him, and very probably poisened him in 54. Claudius was deified later that year. The death of Claudius paved the way for Agrippina's own son, the 16-year-old Lucius Domitius Nero.

Nero (54–69)

Initially, Nero left the rule of Rome to his mother and his tutors, particularly Lucius Annaeus Seneca. However, as he grew older, his desire for power and paranoia increased and he had his mother and tutors executed. During Nero's reign, there were a series of major riots and rebellions throughout the Empire: in Britain, Armenia, Parthia, and Judaea. Nero's inability to manage the rebellions and his basic incompetence became evident quickly and in 68, even the Imperial guard renounced him. Nero is best remembered by the rumour that he played the lyre and sang during the Great Fire of Rome, and hence "fiddled while Rome burned" (though the fiddle had yet to be invented). Nero is also remembered for his immense rebuilding of Rome following the fires. Nero committed suicide, and the year 69 was a year of civil war and is known as the Year of the Four Emperors, with Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian ruling as Emperors in quick and violent succession. By the end of the year, Vespasian was able to solidify his power as emperor of Rome.

Two military "Danger Zones", Rebellions, Uprisings and political consequences

It was relativly easy to rule the Roman Empire, from the central capital of Rome, during peacetime. An eventual rebellion was expected and would happen from time to time: a general or a governor would gain the loyalty of his officers through a mixture of personal charisma, promises and simple bribes. This would be a bad, but not a catastrophic poopies were here with legions which were spread around the borders and the rebel leader would in normal circumstances, have only one or two legions under his command. Loyal legions would be detached from other points of the empire and would eventually drown the rebellion in blood. This happened even more easily in case of a local native uprising as the rebels would normally have no great military experience. Unless the Emperor was weak, incompetent and/or universally despised and hated these rebellions would be a local and isolated event.

During real wartime however, which could develop from a rebellion or a uprising, like the massive Jewish rebellion, this was totally and dangerously different. In a full-blown military campaign the legions under the command of the generals like Vespasian, were of a much greater number. A paranoid or wise emperor would hold some members of the general´s family as hostages, to make certain of the latter´s loyalty. In effect, Nero held Domitian and Quintus Petillius Cerialis the governor of Ostia, who were respectivly, the younger son and the brother-in-law of Vespasian. This would be in normal circumstances quite enough. In fact, the rule of Nero ended with the revolt of the Praetorian Guard who had been bribed in the name of Galba. It became all too obvious that the Praetorian Guard was a sword of Damocles, whose loyalty was all too often bought and who became inceasingly greedy. Following their example the legions at the borders would also increasingly participate in the civil wars. This was a dangerous development as this would weaken the whole Roman Army.

The main enemy, in the West, were arguably in the the "barbarian tribes" behind the Rhine and the Danube. Octavian had tried to conquer them, but ultimatably failed and these "barbarians" were greatly feared. But by the large, they were left in peace, in order to fight amongst themselves, and were simply too divided to pose a greater threat.

The Parthian Empire, in the East, on the other hand, was simply too far away to be conquered. Any Parthian invasion was confronted and usually defeated but the threat itself was ultimately impossible to destroy.

In the case of a Roman civil war these two enemies would seize the oportunity to invade Roman territory in order to raid and plunder. The two respective military frontiers became a matter of major political importance due to the number of the legions stationed there. All too often their generals would rebel, starting a new civil war. Indeed, many emperors would follow this path to power. To control the western border from Rome was relativly easy as it was relativly close. To control both frontiers, at the same time, during wartime, was hard. It was no longer enough to be a good administrator, emperors were increasingly near the troops in order to control them and no single emperor could be at the two frontiers at the same time. This problem would plague the "ruling" emperors time and time again and many "future" emperors would follow this path to power.

Flavian Dynasty

The Flavians, although a relatively short lived dynasty, helped restore stability to an empire on its knees. Although there are criticisms of all three, especially based on their more centralized style of rule, it was the reforms and good rule of the three that helped create a stable empire that would last well into the 3rd Century. However, their background as a military dynasty led to further irrelevancy of the senate, and the move from princeps, or first citizen, to imperator, or emperor, was finalized during their reign.

Vespasian (69–79)

Vespasian was a remarkably successful Roman general who had been given rule over much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire. He had supported the imperial claims of Galba; however, on his death, Vespasian became a major contender for the throne. After the suicide of Otho, Vespasian was able to hijack Rome's winter grain supply in Egypt, placing him in a good position to defeat his remaining rival, Vitellius. On December 20, 69, some of Vespasian's partisans were able to occupy Rome. Vitellius was murdered by his own troops, and the next day, Vespasian was confirmed as Emperor by the Senate. At the age of 60 and battle hardened he was hardly a charismatic emperor, but he turned out to be an excellent ruler none the less.

Although Vespasian was considered quite the autocrat by the senate, he mostly continued the weakening of that body that had been going since the reign of Tiberius. This was typified by his dating his accession to power from July 1, when his troops proclaimed him emperor, instead of December 21, when the Senate confirmed his appointment. Another example was his assumption of the censorship in 73, giving him power over who made up the senate. He used that power to expel dissident senators. At the same time, he increased the number of senators from 200, at that low level due to the actions of Nero and the year of crisis that followed, to 1000, most of the new senators coming not from Rome but from Italy and the urban centers within the western provinces.

Vespasian was able to liberate Rome from the financial burdens placed upon it by Nero's excesses and the civil wars. To do this, he not only increased taxes, but created new forms of taxation. Also, through his power as censor he was able to carefully examine the fiscal status of every city and province, many paying taxes based upon information and structures more than a century old. Through this sound fiscal policy, he was able to build up a surplus in the treasury and embark on public works projects. It was he who first commissioned the Roman Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater); he also built a forum whose centerpiece was a temple to Peace. In addition, he alloted sizable subsidies to the arts, creating a chair of rhetoric at Rome.

Vespasian was also an effective emperor for the provinces in his decades of office, having posts all across the empire, both east and west. In the west he gave considerable favoritism to Spain in which he granted Latin rights to over three hundred towns and cities, promoting a new era of urbanization throughout the western (i.e. formerly barbarian) provinces. Through the additions he made to the Senate he allowed greater influence of the provinces in the Senate, helping to promote unity in the empire. He also extended the borders of the empire on every front, most of which was done to help strengthen the frontier defenses, one of Vespasian's main goals. The crisis of 69 had wrought havoc on the army. One of the most marked problems had been the support lent by provincial legions to men who supposedly represented the best will of their province. This was mostly caused by the placement of native auxiliary units in the areas they were recruited in, a practice Vespasian stopped. He mixed auxiliary units with men from other areas of the empire or moved the units away from where they were recruited to help stop this. Also, to further reduce the chances of another military coup he broke up the legions, and instead of placing them in singular concentrations broke them up along the border. Perhaps the most important military reform he undertook was the extension of legion recruitment from exclusively Italy to Gaul and Spain, in line with the Romanization of those areas.

Titus (79–81)

Titus, the eldest son of Vespasian, had been groomed to rule. He had served as an effective general under his father, helping to secure the east and eventually taking over the command of Roman armies in Syria and Palestine, quelling the significant Jewish revolt going on at the time. He shared the consul for several years with his father and received the best tutelage. Although there was some trepidation when he took office due to his known dealings with some of the less respectable elements of Roman society, he quickly proved his merit, even recalling many exiled by his father as a show of good faith. However, his short reign was marked by disaster: in 79, Vesuvius erupted in Pompeii, and in 80, a fire decimated much of Rome. His generosity in rebuilding after these tragedies made him very popular. Titus was very proud of his work on the vast amphitheater begun by his father. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished edifice during the year 80, celebrating with a lavish show that featured 100 gladiators and lasted 100 days. Titus died in 81, at the age of 41 of what is presumed to be illness; it was rumored that his brother Domitian murdered him in order to become his successor, although these claims have little merit. Whatever the case, he was greatly mourned and missed.

Domitian (81–96)

The Flavians all had rather poor relations with the senate due to their more autocratic style, however Domitian was the only one who truly created significant problems. His continuous control as consul and censor throughout his rule, the former his father sharing in much the same way of his Julio-Claudian forerunners, the latter having difficulty even obtaining, were unheard of. In addition, he often appeared in full military regalia as an imperator, an affront to the idea of what the Principate-era emperor's power was based upon, the emperor as the princeps. His reputation in the Senate aside, he kept the people of Rome happy through various measures, including donations to every resident of Rome, wild spectacles in the newly finished Colosseum, and continuing the public works projects of his father and brother. He also apparently had the good fiscal sense of his father, because although he spent lavishly his successors came to power with a well endowed treasury.

However, during the end of his reign Domitian became extremely paranoid which probably had its initial roots in the treatment he received by his father: although given significant responsibility, he was never trusted with anything important without supervision. This flowered into the severe and perhaps pathological repercussions following the short lived rebellion in 89 of Antonius Saturninus, a governor and commander in Germany. Domitian's paranoia led to a large number of arrests, executions, and seizure of property (which might help explain his ability to spend so lavishly). Eventually it got to the point where even his closest advisers and family members lived in fear, leading them to his murder in 96 orchestrated by his enemies in the Senate, Stephanus (the steward of the deceased Julia Flavia), members of the Pretorian Guard and empress Domitia Longina.

Five Good Emperors - The Antonine Dynasty (96 – 180)

The next century came is known as the period of the "Five Good Emperors", in which the succession was peaceful though not dynastic and the Empire was prosperous. The emperors of this period were Nerva (96–98), Trajan (98–117), Hadrian (117–138), Antoninus Pius (138–161) and Marcus Aurelius (161–180), each being adopted by his predecessor as his successor during the latter's lifetime. While their respective choices of successor were based upon the merits of the individual men they selected, it has been argued that the real reason for the lasting success of the adoptive scheme of succession lay more with the fact that none of them had a natural heir.

Under Trajan, the Empire's borders briefly achieved their maximum extension with provinces created in Mesopotamia in 117. From 166, Roman embassies to China, first sent under the reign of Antonius Pius and probably traveling on the southern sea route, are recorded in Chinese historical sources such as the Later Han History.

Commodus (180–192)

The period of the "five good emperors" was brought to an end by the reign of Commodus from 180 to 192. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius, making him the first direct successor in a century, breaking the scheme of adoptive successors that had turned out so well. He was co-emperor with his father from 177. When he became sole emperor upon the death of his father in 180, it was at first seen as a hopeful sign by the people of the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, as generous and magnanimous as his father was, Commodus turned out to be just the opposite.

Commodus is often thought to have been insane, and he was certainly given to excess. He began his reign by making an unfavorable peace treaty with the Marcomanni, who had been at war with Marcus Aurelius. Commodus also had a passion for gladiatorial combat, which he took so far as to take to the arena himself, dressed as a gladiator. In 190, a part of the city of Rome burned, and Commodus took the opportunity to "re-found" the city of Rome in his own honor, as Colonia Commodiana. The months of the calendar were all renamed in his honor, and the senate was renamed as the Commodian Fortunate Senate. The army became known as the Commodian Army. Commodus was strangled in his sleep in 192, a day before he planned to march into the Senate dressed as a gladiator to take office as a consul. Upon his death, the Senate passed damnatio memoriae on him and restored the proper name to the city of Rome and its institutions. The popular movies The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and Gladiator (2000) were loosely based on the career of the emperor Commodus, although they should not be taken as accurate historical depictions of his life.

Severan dynasty (193–235)

The Severan dynasty includes the increasingly troubled reigns of Septimius Severus (193–211), Caracalla (211–217), Macrinus (217–218), Elagabalus (218–222), and Alexander Severus (222–235). The founder of the dynasty, Lucius Septimius Severus, belonged to a leading native family of Leptis Magna in Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their provincial background and cosmopolitan alliance, eventually giving rise to imperial rulers of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testifies to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire that had been achieved under the Antonines. A generally successful ruler, Septimius Severus cultivated the army's support with substantial remuneration in return for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power base of the imperial administration throughout the empire. Abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times, Septimius Severus was likewise able to transfer additional power to the executive branch of the government, of which he was decidedly the chief representative.

Septimius Severus' son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus — nicknamed Caracalla — removed all legal and political distinction between Italians and provincials, enacting the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 which extended full Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous Baths of Caracalla in Rome, their design serving as an architectural model for many subsequent monumental public buildings. Increasingly unstable and autocratic, Caracalla was assassinated by the praetorian prefect Macrinus in 217, who succeeded him briefly as the first emperor not of senatorial rank. The imperial court, however, was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in 218, and Alexander Severus, the last of the dynasty, in 222. In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was somewhat revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. Despite early successes against the Sassanian Empire in the East, Alexander Severus' increasing inability to control the army led eventually to its mutiny and his assassination in 235. The death of Alexander Severus ushered in a subsequent period of soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife.

Crisis of the 3rd Century (235–284)

The Crisis of the 3rd Century is a commonly applied name for the crumbling and near collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 284. During this period, Rome was ruled by more than 35 individuals, most of them prominent generals who assumed Imperial power over all or part of the empire, only to lose it by defeat in battle, murder, or death. After nearly 50 years of external invasion, internal civil wars and economic chaos, the Empire was on the verge of ending. A series of tough soldier-emperors saved the empire, but in the process fundamentally changed the Roman Empire. The transitions of this period mark the beginnings of Late Antiquity and the end of Classical Antiquity.

Tetrarchy (285–324)

The transition from a single united empire to the later divided Western and Eastern empires was a gradual transformation. In July, 285, Diocletian defeated rival Emperor Carinus and briefly became sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

Diocletian saw that the vast Roman Empire was ungovernable by a single emperor in the face of internal pressures and military threats on two fronts. He therefore split the Empire in half along a north-west axis just east of Italy, and created two equal Emperors to rule under the title of Augustus. Diocletian was Augustus of the eastern half, and gave his long time friend Maximian the title of Augustus in the western half.

In 293 authority was further divided as each Augustus took a Caesar to aid him in administrative matters, and to provide a line of succession; Galerius became the junior emperor of Diocletian and Constantius Chlorus the junior emperor of Maximian. This constituted what is called the Tetrarchy (in Greek: the leadership of four) by modern scholars. The system allowed the peaceful succession of the Augusti as the Caesar in each half rose up to replace the Augustus and proclaimed a new Caesar. On May 1, 305 Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in favor of their Caesars. Galerius named the two new Caesars: his nephew Maximinus for himself and Flavius Valerius Severus for Constantius.

The Tetrarchy would effectively collapse with the death of Constantius Chlorus on July 25 306. Constantius' troops in Eboracum immediately proclaimed his son Constantine an Augustus. In August, 306, Galerius promoted Severus to the position of Augustus. A revolt in Rome supported another claimant to the same title: Maxentius, son of Maximian, who was proclaimed Augustus on October 28, 306. His election was supported by the Praetorian Guard. This left the Empire with five rulers: four Augusti (Galerius, Constantine, Severus and Maxentius) and a Caesar (Maximinus).

The year 307 saw the return of Maximian to the role of Augustus alongside his son Maxentius creating a total of six rulers of the Empire. Galerius and Severus campaigned against them in Italy. Severus was killed under command of Maxentius on September 16, 307. The two Augusti of Italy also managed to ally themselves with Constantine by having Constantine marry Fausta, the daughter of Maximian and sister of Maxentius. The end of 307 saw the Empire with four Augusti (Maximian, Galerius, Constantine and Maxentius) and a sole Caesar (Maximinus).

The five were briefly joined by another Augustus in 308, Domitius Alexander, vicarius of the Roman province of Africa under Maxentius, proclaimed himself Augustus. Before long he was captured by Rufius Volusianus and Zenas. Alexander was executed in 311. The current situation of conflict between the various rivalrous Augusti was resolved in the Congress of Carnuntum with the participation of Diocletian, Maximian and Galerius. The final decisions were taken on November 11, 308:

- Galerius remained Augustus of the Eastern Roman Empire.

- Maximinus remained Caesar of the Eastern Roman Empire.

- Maximian was forced to abdicate.

- Maxentius was still not recognized, his rule remained illegitimate.

- Constantine received official recognition but was demoted to Caesar of the Western Roman Empire.

- Licinius replaced Maximian as Augustus of the Western Roman Empire.

Problems however continued. Maximinus demanded to be promoted to Augustus. He proclaimed himself to be one on May 1 310; Constantine followed suit shortly after. Maximian similarly proclaimed himself an Augustus for a third and final time. He was killed by his son-in-law Constantine in July, 310. The end of the year again found the Empire with four legitimate Augusti (Galerius, Maximinus, Constantine and Licinius) and one illegitimate one (Maxentius).

Galerius died in May 311 leaving Maximinus sole ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire. Meanwhile Maxentius declared a war on Constantine under the pretext of avenging his executed father. He was among the casualties of the Battle of Milvian Bridge on October 28 312.

This left the Empire in the hands of the three remaining Augusti, Maximinus, Constantine and Licinius. Licinius allied himself with Constantine, cementing the alliance by marriage to his younger half-sister Constantia in March 313 and joining open conflict with Maximinus. In August 313 Maximinus met his death at Tarsus in Cilicia. The two remaining Augusti divided the Empire again in the pattern established by Diocletian, Constantine becoming Augustus of the Western Roman Empire and Licinius Augustus of the Eastern Roman Empire.

This division lasted ten years until 324. A final war between the last two remaining Augusti ended with the deposition of Licinius and the elevation of Constantine to sole Emperor of the Roman Empire. Deciding that the empire needed a new capital, Constantine chose the site of Byzantium for the new city. He refounded it as Nova Roma, but it was popularly called Constantinople: Constantine's City.

Christian Empire (324–395)

The beginning of the Roman Empire as a Christian empire lies in 313, with the Edict of Milan. The edict was signed under the reigns of Constantine I and Licinius. The edict established tolerance for Christianity throughout the Empire, but did not yet make it the official state religion. After the Edict was proclaimed, however, the Christian Church rapidly became extremely influential amongst the ruling classes of the Empire, and the Bishops were established in positions of power and influence.

Christianity became the single official religion of Rome under Theodosius I (r. 379–395). The emperor had a considerable degree of control over the church. While Christianity flourished, the Empire by no means became uniformly Christian; paganism remained significant. Theodosius massacred Thessalonica for rebelling against his new Christian policies condemning homosexuality, which was a common practice in both ancient Greece and Greece under Roman rule. Upon his return to Rome the Bishop Ambrose refused to let Theodosius enter the church until he made a public repentance. Theodosius did so, and from then on the church's powers grew. Eventually the church would gain enough power that it would outlast the empire in the west.

Late Antiquity in the West (395–476)

The year 476 AD is generally accepted as the end of the Western Roman Empire. In that year, Odoacer deposed his puppet Romulus Augustus (475–476), and for the first time did not bother to induct a successor, choosing instead to rule as a representative of the Eastern Emperor (although Julius Nepos, the emperor deposed by Romulus Augustulus, continued to rule Illyricum until his death in 480, at which point Odoacer annexed this remant of the Western Empire to his Italian kingdom). The last Emperor who ruled over the whole Empire from Rome, however, had been Theodosius, who removed the seat of power to Mediolanum (Milan). Edward Gibbon, in writing The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire knew not to end his narrative at 476. The great corpse continued to twitch, into the 6th century.

On the other hand, in 409, with the Emperor of the West fled from Milan to Ravenna and all the provinces wavering in loyalties, the Goth Alaric I, in charge at Rome, came to terms with the senate, and with their consent set up a rival emperor and invested the prefect of the city, a Greek named Priscus Attalus, with the diadem and the purple robe. In the following year when the Goths rampaged in the City, local power was in the hands of the Bishop of Rome. The transfer of power to Christian pope and military dux had been effected: the Western Empire was effectively dead, though no contemporary knew it.

The next seven decades played out as aftermath. Theodoric the Great as King of the Goths, couched his legitimacy in diplomatic terms as being the representative of the Emperor of the East. Consuls were appointed regularly through his reign: a formula for the consular appointment is provided in Cassiodorus' Book VI. The post of consul was last filled in the west by Theodoric's successor, Athalaric, until he died in 534. Ironically the Gothic War in Italy, which was meant as the reconquest of a lost province for the Emperor of the East and a re-establishment of the continuity of power, actually caused more damage and cut more ties of continuity with the Antique world than the attempts of Theodoric and his minister Cassiodorus to meld Roman and Gothic culture within a Roman form.

In essence, the "fall" of the Roman Empire to a contemporary depended a great deal on where they were and their status in the world. On the great villas of the Italian Campagna, the seasons rolled on without a hitch. The local overseer may have been representing an Ostrogoth, then a Lombard duke, then a Christian bishop, but the rhythm of life and the horizons of the imagined world remained the same. Even in the decayed cities of Italy consuls were still elected. In Auvergne, at Clermont, the Gallo-Roman poet and diplomat Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont, realized that the local "fall of Rome" came in 475, with the fall of the city to the Visigoth Euric. In the north of Gaul the Franks could not be taken for Roman, but in Hispania the last Arian Visigothic king Liuvigild considered himself the heir of Rome. In Alexandria, dreams of a "Christian Empire" with genuine continuity were shattered when a rampaging mob of Christians were encouraged to sack and destroy the Serapeum in 392. Hispania Baetica was still essentially Roman when the Moors came in 711, but in the northwest, the invasion of the Suevi broke the last frail links with Roman culture in 409. In Aquitania and Provence, cities like Arles were not abandoned, but Roman culture in Britain collapsed in waves of violence after the last legions evacuated: the final legionary probably left Britain in 409. In Athens the end came for some in 529, when the Emperor Justinian closed the Neoplatonic Academy and its remaining members fled east for protection under the rule of Sassanid king Khosrau I; for other Greeks it had come long before, in 396, when Christian monks led Alaric I to vandalize the site of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

From Roman to Byzantine in the East

Under Constantine (330–337) and his sons (337–361)

Constantinople would serve as the capital of Constantine the Great from May 11, 330 to his death on May 22 337. The Empire was parted again among his three surviving sons.The Western Roman Empire was divided among the eldest son Constantine II and the youngest son Constans. The Eastern Roman Empire along with Constantinople were the share of middle son Constantius II.

Constantine II was killed in conflict with his youngest brother in 340. Constans was himself killed in conflict with army proclaimed Augustus Magnentius on January 18 350. Magnentius was at first opposed in the city of Rome by self-proclaimed Augustus Nepotianus, a paternal first cousin of Constans. Nepotianus was killed alongside his mother Eutropia. His other first cousin Constantia convinced Vetriano to proclaim himself Caesar in opposition to Magnentius. Vetriano served a brief term from March 1 to December 25 350. He was then forced to abdicate by the legitimate Augustus Constantius. The usurper Magnentius would continue to rule the Western Roman Empire till 353 while in conflict with Constantius. His eventual defeat and suicide left Constantius as sole Emperor.

Constantius' rule would however be opposed again in 360. He had named his paternal half-cousin and brother-in-law Julian as his Caesar of the Western Roman Empire in 355. During the following five years, Julian had a series of victories against invading Germanic tribes, including the Alamanni. This allowed him to secure the Rhine frontier. His victorious Gallic troops thus ceased campaigning. Constantius send orders for the troops to be transferred to the east as reinforcements for his own currently unsuccessful campaign against Shapur II of Persia. This order led the Gallic troops to an insurrection. They proclaimed their commanding officer Julian to be an Augustus. Both Augusti were not ready to lead their troops to another Roman Civil War. Constantius' timely demise on November 3, 361 prevented this war from ever occurring.

Under Julian & Jovian (361–364)

Julian would serve as the sole Emperor for two years. He had received his baptism as a Christian years before, but apparently no longer considered himself one. His reign would see the ending of restriction and persecution of paganism introduced by his uncle and father-in-law Constantine the Great and his cousins and brothers-in-law Constantine II, Constans and Constantius II. He instead placed similar restrictions and unofficial persecution of Christianity. His edict of toleration in 362 ordered the reopening of pagan temples and the reinstitution of alienated temple properties, and, more problematically for the Christian Church, the recalling of previously exiled Christian bishops. Returning Orthodox and Arian bishops resumed their conflicts, thus further weakening the Church as a whole.

Julian himself was not a traditional pagan. His personal beliefs were largely influenced by Neoplatonism and Theurgy; he reputedly believed he was the reincarnation of Alexander the Great. He produced works of philosophy arguing his beliefs. His brief renaissance of paganism would, however, end with his death. Julian eventually resumed the war against Shapur II of Persia. He received a mortal wound in battle and died on June 26, 363. He was considered a hero by pagan sources of his time and a villain by Christian ones. Later historians have treated him as a controversial figure.

Julian died childless and with no designated successor. The officers of his army elected the rather obscure officer Jovian emperor. He is remembered for signing an unfavorable peace treaty with Persia and restoring the privileges of Christianity. He is considered a Christian himself, though little is known of his beliefs. Jovian himself died on February 17, 364.

Valentinian Dynasty (364–392)

The role of choosing a new Augustus fell again to army officers. On February 28, 364, Pannonian officer Valentinian I was elected Augustus in Nicaea, Bithynia. However, the army had been left leaderless twice in less than a year, and the officers demanded Valentinian to choose a co-ruler. On March 28 Valentinian chose his own younger brother Valens and the two new Augusti parted the Empire in the pattern established by Diocletian: Valentinian would administer the Western Roman Empire, while Valens took control over the Eastern Roman Empire.

Valens' election would soon be disputed. Procopius, a Cilician maternal cousin of Julian, had been considered a likely heir to his cousin but was never designated as such. He had been in hiding since the election of Jovian. In 365, while Valentinian was at Paris and then at Reims to direct the operations of his generals against the Alamanni, Procopius managed to bribe two legions assigned to Constantinople and take control of the Eastern Roman capital. He was proclaimed Augustus on September 28 and soon extended his control to both Thrace and Bithynia. War between the two rival Eastern Roman Emperors continued until Procopius was defeated. Valens had him executed on May 27, 366.

On August 4 367, a 3rd Augustus was proclaimed by the other two. His father Valentinian and uncle Valens chose the 8 year-old Gratian as a nominal co-ruler, obviously as a means to secure succession.

In April 375 Valentinian I led his army in a campaign against the Quadi, a Germanic tribe which had invaded his native province of Pannonia. During an audience to an embassy from the Quadi at Brigetio on the Danube (part of modern-day Komárom, Hungary), Valentinian suffered a burst blood vessel in the skull while angrily yelling at the people gathered. This injury resulted in his death on November 17, 375.

Succession did not go as planned. Gratian was then a sixteen-year-old and arguably ready to act as Emperor, but the troops in Pannonia proclaimed his infant half-brother emperor under the title Valentinian II.

Gratian acquiesced in their choice and administrated the Gallic part of the Western Roman Empire. Italy, Illyria and Africa were officially administrated by his brother and his step-mother Justina. However the division was merely nominal as the actual authority still rested with Gratian.

Battle of Adrianople (378)

Meanwhile the Eastern Roman Empire faced its own problems with Germanic tribes. The East Germanic tribe known as the Goths were forced to flee their former lands following an invasion by the Huns. Their leaders Alavinus and Fritigern led them to seek refuge from the Eastern Roman Empire. Valens indeed let them settle as foederati on the southern bank of the Danube in 376. However the newcomers faced problems from allegedly corrupted provincial commanders and a series of hardships. Their dissatisfaction led them to revolt against their Roman hosts.

For the following two years conflicts continued. Valens personally led a campaign against them in 378. Gratian provided his uncle with reinforcements from the Western Roman army. However this campaign proved disastrous for the Romans. The two armies approached each other near Adrianople. Valens was apparently overconfident of his numerical superiority of his own forces over the Goths. His officers advised him to wait for the promised arrival of Gratian himself with further reinforcements. But Valens instead rushed to battle. On August 9, 378, the Battle of Adrianople resulted in the crushing defeat of the Romans and the death of Valens. Contemporary historian Ammianus Marcellinus estimated that two thirds of the Roman army were lost in the battle. The last third managed to retreat.

The battle had far reaching consequences. Veteran soldiers and valuable administrators were among the heavy casualties. There were few available replacements at the time. Leaving the Empire with problems of finding suitable leadership. The Roman army would also start facing recruiting problems. In the following century much of the Roman army would consist of Germanic mercenaries.

For the moment however there was another concern. The death of Valens left Gratian and Valentinian II as the sole two Augusti. Gratian was now effectively responsible for the whole of the Empire. He sought however, a replacement Augustus for the Eastern Roman Empire. His choice was Theodosius I, son of formerly distinguished general Count Theodosius. The elder Theodosius had been executed in early 375 for unclear reasons. The younger one was named Augustus of the Eastern Roman Empire on January 19 379. His appointment would prove a deciding moment in the division of the Empire.

Disturbed peace in the West (383)

Gratian governed the Western Roman Empire with energy and success for some years, but he gradually sank into indolence. He is considered to have become a figurehead while Frankish general Merobaudes and bishop Ambrose of Milan jointly acted as the power behind the throne. Gratian lost favor with factions of the Roman Senate by prohibiting traditional paganism at Rome and relinquishing his title of Pontifex Maximus. The senior Augustus also became unpopular to his own Roman troops due to his close association with so-called barbarians. He reportedly recruited Alans to his personal service and adopted the guise of a Scythian warrior for public appearances.

Meanwhile Gratian, Valentinian II and Theodosius were joined by a fourth Augustus. Theodosius proclaimed his oldest son Arcadius to be an Augustus in January, 383 in an obvious attempt to secure succession. The boy was only still five or six years old and held no actual authority. Nevertheless he was recognized as a co-ruler by all three Augusti.

The increasing unpopularity of Gratian would cause the four Augusti problems later that same year. Spanish Celt general Magnus Maximus, stationed in Roman Britain, was proclaimed Augustus by his troops in 383 and rebelling against Gratian he invaded Gaul. Gratian fled from Lutetia (Paris) to Lugdunum (Lyon), where he was assassinated on August 25, 383 at the age of twenty-five.

Maximus was a firm believer of the Nicene Creed and introduced state persecution on charges of heresy, which brought him in conflict with Pope Siricius who argued that the Augustus had no authority over church matters. But he was an Emperor with popular support and his reputation survived in Romano-British tradition and gained him a place in the Mabinogion, compiled about a millennium after his death.

Following Gratian's death, Maximus had to deal with Valentinian II, actually only twelve year old, as the senior Augustus. The first few years the Alps would serve as the borders between the respective territories of the two rival Western Roman Emperors. Maximus controlled Britain, Gaul, Hispania and Africa. He chose Augusta Treverorum (Trier) as his capital.

Maximus soon entered negotiations with Valentinian II and Theodosius, attempting to gain their official recognition. By 384, negotiations were unfruitful and Maximus tried to press the matter by settling succession as only a legitimate Emperor could do: proclaiming his own infant son Flavius Victor an Augustus. The end of the year find the Empire having five Augusti (Valentinian II, Theodosius I, Arcadius, Magnus Maximus and Flavius Victor) with relations between them yet to be determined.

Theodosius was left a widower, in 385, following the sudden death of Aelia Flaccilla, his Augusta.He was remarried to the sister of Valentinean II, Galla, and the marriage secured closer relations between the two legitimate Augusti.

In 386 Maximus and Victor finally received official recognition by Theodosius but not Valentinian. In 387, Maximus apparently decided to rid himself of his Italian rival. He crossed the Alps into the valley of the Po and threatened Milan. Valentinian and his mother fled to Thessaloniki from where they sought the support of Theodosius. Theodosius indeed campaigned west in 388 and was victorious against Maximus. Maximus himself was captured and executed in Aquileia on July 28, 388. Magister militum Arbogastes was sent to Trier with orders to also kill Flavius Victor. Theodosius restored Valentinian to power and through his influence had him converted to Orthodox Catholicism. Theodosius continued supporting Valentinian and protecting him from a variety of usurpations.

Theodosian Dynasty (392–395)

In 392 Valentinian was murdered in Vienne. Theodosius succeeded him, ruling the entire Roman Empire.

Theodosius had two sons and a daughter, Pulcheria, from his first wife, Aelia Flacilla. His daughter and wife died in 385. By his second wife, Galla, he had a daughter, Galla Placidia, the mother of Valentinian III, who would be Emperor of the West.

After his death in 395 he gave the two halves of the Empire to his two sons Arcadius and Honorius; Arcadius became ruler in the East, with his capital in Constantinople, and Honorius became ruler in the west, with his capital in Milan. Though the Roman state would continue to have two emperors, the Eastern Romans considered themselves Roman in full. Latin was used in official writings as much as, if not more than, Greek. The two halves were nominally, culturally and historically, if not politically, the same state.

Later Eastern Empire (476–1461)

The west would continue to decline during the 5th century. However, the richer east would be spared much of the destruction. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 by Odoacer, the half Hunnish, half Scirian chieftain of the Germanic Heruli. The Eastern Empire counter-attacked in the 6th century under the eastern emperor Justinian I, taking much of the west back. These gains were lost during subsequent reigns. Of the many accepted dates for the end of the Roman state, the latest is 610. This is when the Emperor Heraclius made sweeping reforms, forever changing the face of the empire. Greek was readopted as the language of government and Latin influence waned. By 610, the Classical Roman Empire had evolved into the Middle Age Byzantine Empire, although it was never called this (rather it was called Romania or Basileia Romaion) and the Byzantines continued to consider themselves Romans until their fall in the 15th century, after which their modern descendants the Greeks have continued to call themselves Romaioi (Romans) to this day. The modern Aromanians, Rumarians and Romanians also use ethnonyms that derive from Romanus.

Several states claiming to be the Roman Empire's successor arose, before as well as after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Holy Roman Empire, an attempt to resurrect the Empire in the West, was established in 800 when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as Roman Emperor on Christmas Day, though the empire and the imperial office did not become formalized for some decades. After the fall of Constantinople, the Russian Empire, as inheritor of the Byzantine Empire's Orthodox Christian tradition, counted itself as the third Rome (with Constantinople being the second). And when the Ottomans, who based their state around the Byzantine model, took Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II established his capital there and claimed to sit on the throne of the Roman Empire, and he even went so far as to launch an invasion of Italy with the purpose of "re-uniting the Empire", although Papal and Neapolitan armies stopped his march on Rome at Otranto in 1480. Constantinople was not officially renamed to Istanbul until March 28, 1930.

But excluding these states claiming their heritage, the Romans lasted, from the founding of Rome in 753 BC, to the fall in 1461 of the Empire of Trebizond (a successor state and fragment of the Byzantine Empire which escaped conquest by the Ottomans in 1453), for a total of 2214 years. Their impact on Western and Eastern civilizations lives on. In time most of the Roman achievements have been duplicated by later civilizations. For example, the technology for cement was rediscovered 1755–1759 by John Smeaton.

Roman Provinces

Main article Roman province Template:Roman provinces 120 AD

See also

Emperors

| Roman emperors by time period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

Ancient Historians of the Empire

In Latin

- Livy, wrote about the history is of the Roman Republic, but during Augustus' reign

- Suetonius

- Gaius Cornelius Tacitus

- Ammianus Marcellinus

In Greek

Latin Literature of the Empire

References

18th & 19th century historians

Modern historians of the Roman Empire

- J. B. Bury, A History of the Roman Empire from its Foundation to the death of Marcus Aurelius, 1913

- J. A. Crook, Law and Life of Rome, 90 BC–AD 212, 1967, ISBN 0-801-492-734

- S. Dixon, The Roman Family, 1992, ISBN 0-801-842-00X

- D.R. Dudley, The Civilization of Rome, 2nd ed., 1985, ISBN 0-452-010-160

- A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284–602, 1964, ISBN 0-801-832-853

- A. Lintott, Imperium Romanum: Politics and administration, 1993, ISBN 0-415-093-759

- R. Macmullen, Roman Social Relations, 50 BC to AD 284, 1981, ISBN 0-300-027-028

- M.I. Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire 2nd ed., 1957

- R. Syme, The Roman Revolution, 1939, ISBN 0-192-803-204

- C. Wells, The Roman Empire, 2nd ed., 1992, ISBN 0-006-862-527

External links

- Roman History Chronology World History Database

- Interactive Map of the Roman Empire from resourcesforhistory.com

- The Tabula Peutingeriana, a Medieval copy of a Roman map of the Roman Empire

- www.roman-empire.net An extensive site on the Roman Empire.

- A virtual tour of Ancient Rome with pictures and virtual reality movies

- The Roman Empire with an archive of many texts about the Roman Empire

- Grout, James, "Encyclopaedia Romana"

- J. O'Donnell, Worlds of Late Antiquity website: links, bibliographies: Augustine, Boethius, Cassiodorus etc.

- Roman Life Expectancy

- Portrait gallery of Roman emperors

- The Roman Empire in the First Century from PBS. Resources about Emperors, poets and philosophers of Rome, life in the 1st Century AD, and an "Emperor of Rome" game

- Rulers of ancient Rome a list of rulers in the Roman world from 753 BC - 476 AD