| Revision as of 09:16, 25 July 2010 edit184.77.84.89 (talk) →SymbolismTag: references removed← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:51, 29 July 2010 edit undoBeyond My Ken (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, IP block exemptions, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers263,266 edits recolumnize "see also", adjust bottomhierarchy & layout, alpha biblio entriesNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | {{Refimprove|date=May 2007}} | ||

| {{Cleanup|date=July 2010}} | {{Cleanup|date=July 2010}} | ||

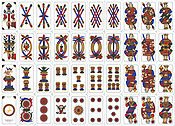

| ] by ]]] | ] by ]]] | ||

| ] brand]] | ] brand]] | ||

| Line 470: | Line 467: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{col-begin}}{{col-break}} | |||

| {{multicol}} | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] {{nb10}} | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | {{col-break}} | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] {{nb10}} | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] are used for parapsychology | * ] are used for parapsychology | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | {{col-end}} | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| ⚫ | ] - The Card Players, 1895]] | ||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist|group=notes}} | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| ;Explanatory notes | |||

| ⚫ | ] - The Card Players, 1895]] | ||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist|group=notes}} | ||

| ;Citations | |||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| <!--spacing--> | |||

| ⚫ | {{Refimprove|date=May 2007}} | ||

| ;Bibliography | |||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| ⚫ | * Griffiths, Antony. ''Prints and Printmaking'' British Museum Press (in UK),2nd edn, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X | ||

| ⚫ | * Hind, Arthur M. ''An Introduction to a History of Woodcut''. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0 | ||

| *Lo, Andrew. "The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards," ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', University of London, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2000): 389-406. | *Lo, Andrew. "The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards," ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', University of London, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2000): 389-406. | ||

| * {{Citation | last =Needham | first =Joseph | author-link =Joseph Needham | year =2004 | title =Science & Civilisation in China | publisher =Cambridge University Press | volume =V:1 | isbn =0521058023}} | * {{Citation | last =Needham | first =Joseph | author-link =Joseph Needham | year =2004 | title =Science & Civilisation in China | publisher =Cambridge University Press | volume =V:1 | isbn =0521058023}} | ||

| * {{Citation |last=Parlett |first=David | author-link=David Parlett |title=The Oxford Guide to Card Games |year= 1990 |publisher=] |isbn=0-19-214165-1}} | * {{Citation |last=Parlett |first=David | author-link=David Parlett |title=The Oxford Guide to Card Games |year= 1990 |publisher=] |isbn=0-19-214165-1}} | ||

| * Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library MS Add. 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352 | * Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library MS Add. 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352 | ||

| ⚫ | * An Introduction to a History of Woodcut |

||

| ⚫ | * Prints and Printmaking |

||

| ⚫ | * {{Citation | last=Wilkinson | first=W.H. | title=Chinese Origin of Playing Cards | journal=The American Anthropologist | volume=VIII | year=1895 | pages=61–78 | url=http://www.gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca/Archives/Wilkinson/Wilkinson.html | doi=10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070 }} | ||

| * {{Citation | last=Singer | first=Samuel Weller | title=Researches into the History of Playing Cards | url=http://books.google.com/?id=ZTMCAAAAYAAJ | publisher=R. Triphook | year=1816 |ref=Singer }} | * {{Citation | last=Singer | first=Samuel Weller | title=Researches into the History of Playing Cards | url=http://books.google.com/?id=ZTMCAAAAYAAJ | publisher=R. Triphook | year=1816 |ref=Singer }} | ||

| ⚫ | * {{Citation | last=Wilkinson | first=W.H. | title=Chinese Origin of Playing Cards | journal=The American Anthropologist | volume=VIII | year=1895 | pages=61–78 | url=http://www.gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca/Archives/Wilkinson/Wilkinson.html | doi=10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070 }} | ||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| Line 515: | Line 520: | ||

| {{Wiktionary|playing card}} | {{Wiktionary|playing card}} | ||

| {{Wikisource1911Enc|Cards, playing}} | {{Wikisource1911Enc|Cards, playing}} | ||

| {{commons}} | {{commons}} | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 525: | Line 529: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| <!--spacing--> | |||

| {{Tarot Cards}} | {{Tarot Cards}} | ||

Revision as of 20:51, 29 July 2010

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (July 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A playing card is a piece of specially prepared heavy paper, thin cardboard, or thin plastic, figured with distinguishing motifs and used as one of a set for playing card games. Playing cards are typically palm-sized for convenient handling.

A complete set of cards is called a pack or deck, and the subset of cards held at one time by a player during a game is commonly called a hand. A deck of cards may be used for playing a great variety of card games, some of which may also incorporate gambling. Because playing cards are both standardized and commonly available, they are often adapted for other uses, such as magic tricks, cartomancy, encryption, board games, or building a house of cards.

The front (or "face") of each card carries markings that distinguish it from the other cards in the deck and determine its use under the rules of the game being played. The back of each card is identical for all cards in any particular deck, and usually of a single color or formalized design. The back of playing cards is sometimes used for advertising. For most games, the cards are assembled into a deck, and their order is randomized by shuffling.

History

Early history

Playing cards were found in China as early as the 9th century during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), when relatives of a princess played a "leaf game". The Tang writer Su E (obtained a jinshi degree in 885) stated that Princess Tongchang (?–870), daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang (r. 860–874), played the leaf game with members of the Wei clan to pass the time. The Song Dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserted that card games existed since the mid Tang Dynasty and associated their invention with the simultaneous development of using sheets or pages instead of paper rolls as a writing medium. A book called Yezi Gexi was allegedly written by a Tang era woman, and was commented on by Chinese writers of subsequent dynasties.

Ancient Chinese "money cards" have four "suits": coins (or cash), strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), myriads (of coins or of strings), and tens of myriads (where a myriad is 10000). These were represented by ideograms, with numerals of 2–9 in the first three suits and numerals 1–9 in the "tens of myriads". Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which were both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for, as in trading card games. The designs on modern Mahjong tiles likely evolved from those earliest playing cards. However, it may be that the first deck of cards ever printed was a Chinese domino deck, in whose cards we can see all the 21 combinations of a pair of dice. In Kuei-t'ien-lu, a Chinese text redacted in the 11th century, we find that dominoes cards were printed during the Tang Dynasty, contemporary to the first printed books. The Chinese word pái (牌) is used to describe both paper cards and gaming tiles.

Introduction into Europe

Further information: TarotPurported evidence of playing cards in Europe prior to the second half of the 14th century is widely regarded as spurious: The 38th canon of the council of Worcester (1240) is often quoted as evidence of cards having been known in England in the middle of the 13th century, but the games de rege et regina (concerning the king and the queen) there mentioned are now thought to more likely have been chess. The background of an 11th century textile appears to feature hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades. It is known as “Bishop Gunther’s shroud” made in Constantinople, and now in Bamberg Cathedral. If cards were generally known in Europe as early as 1278, it is very remarkable that Petrarch, in his work De remediis utriusque fortunae (On the remedies of good/bad fortunes) that treats gaming, never once mentions them.

A miniature of courtiers playing cards with the king can be found in the Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (c. 1352), produced for King Louis II of Naples.

Playing cards first entered Europe in the late 14th century, probably from Mamluk Egypt, with suits very similar to the tarot suits of Swords, Staves, Cups and Coins (also known as disks, and pentacles) and those still used in traditional Italian, Spanish and Portuguese decks. The first documentary evidence is a ban on their use in 1367, Bern, Switzerland. Wide use of playing cards in Europe can, with some certainty, be traced from 1377 onwards.

The Mameluke deck contained 52 cards comprising four "suits": polo sticks, coins, swords, and cups. Each suit contained ten "spot" cards (cards identified by the number of suit symbols or "pips" they show) and three "court" cards named malik (King), nā'ib malik (Viceroy or Deputy King), and thānī nā'ib (Second or Under-Deputy). The Mameluke court cards showed abstract designs not depicting persons (at least not in any surviving specimens) though they did bear the names of military officers.

A complete pack of Mameluke playing cards was discovered by Leo Mayer in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, in 1939; this particular complete pack was not made before 1400, but the complete deck allowed matching to a private fragment dated to the 12th or 13th century. In effect it is not a complete deck, but there are cards of three packs of the same style.

It is not known whether these cards influenced the design of the Indian cards used for the game of Ganjifa, or whether the Indian cards may have influenced these. Regardless, the Indian cards have many distinctive features: they are round, generally hand painted with intricate designs, and comprise more than four suits (often as many as thirty two, like a deck in the Deutsches Spielkarten-Museum, painted in the Mewar, a city in Rajasthan, between the 18th and 19th century. Decks used to play have from eight up to twenty suits).

Spread across Europe and early design changes

In the late 14th century, the use of playing cards spread rapidly throughout Europe. Documents mentioning cards date from 1371 in Spain, 1377 in Switzerland, and 1380 in many locations including Florence and Paris. A 1369 Paris ordinance does not mention cards, but its 1377 update does. In the account books of Johanna, duchess of Brabant and Wenceslaus I, duke of Luxemburg, an entry dated May 14, 1379, reads: "Given to Monsieur and Madame four peters, two forms, value eight and a half moutons, wherewith to buy a pack of cards". In his book of accounts for 1392 or 1393, Charles or Charbot Poupart, treasurer of the household of Charles VI of France, records payment for the painting of three sets of cards.

The earliest cards were made by hand, like those designed for Charles VI; this was expensive. Printed woodcut decks appeared in the 15th century. The technique of printing woodcuts to decorate fabric was transferred to printing on paper around 1400 in Christian Europe, very shortly after the first recorded manufacture of paper there, while in Islamic Spain it was much older. The earliest dated European woodcut is 1418. No examples of printed cards from before 1423 survive. But from about 1418 to 1450 professional card makers in Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg created printed decks. Playing cards even competed with devotional images as the most common uses for woodcut in this period.

Most early woodcuts of all types were coloured after printing, either by hand or, from about 1450 onwards, stencils. These 15th century playing cards were probably painted.

The Master of the Playing Cards worked in Germany from the 1430s with the newly invented printmaking technique of engraving. Several other important engravers also made cards, including Master ES and Martin Schongauer. Engraving was much more expensive than woodcut, and engraved cards must have been relatively unusual.

In the 15th century in Europe, the suits of playing cards varied; typically a deck had four suits, although five suits were common and other structures are also known. In Germany, hearts (Herz/Dolle/Rot), bells (Schall), leaves (Grün), and acorns (Eichel) became the standard suits and are still used in Eastern and Southeastern German decks today for Skat, Schafkopf, Doppelkopf, and other games. Italian and Spanish cards of the 15th century used swords, batons (or wands), cups, and coins (or rings). The Tarot, which included extra trump cards, was invented in Italy in the 15th century.

The four suits now used in most of the world — spades, hearts, diamonds, and clubs — originated in France in approximately 1480. The trèfle (club) was probably copied from the acorn and the pique (spade) from the leaf of the German suits. The names "pique" and "spade", however, may have derived from the sword of the Italian suits. In England, the French suits were eventually used, although the earliest decks had the Italian suits .

Also in the 15th century, Europeans changed the court cards to represent European royalty and attendants, originally "king", "chevalier" (knight), and "knave" (or "servant"). In a German pack from the 1440s, Queens replace Kings in two of the suits as the highest card. Fifty-six-card decks containing a King, Queen, Knight, and Valet (from the French tarot court) were common.

Court cards designed in the 16th century in the manufacturing centre of Rouen became the standard design in England, while a Parisian design became standard in France. Both the Parisian and Rouennais court cards were named after historical and mythological heroes and heroines. The Parisian names have become more common in modern use, even with cards of Rouennais design.

| Modern paris court card name | Traditional paris court card name |

|---|---|

| King of Spades | David |

| King of Hearts | Charles (possibly Charlemagne, or Charles VII, where Rachel would then be the pseudonym of his mistress, Agnès Sorel) |

| King of Diamonds | Julius Caesar |

| King of Clubs | Alexander the Great |

| Queen of Spades | Pallas |

| Queen of Hearts | Judith |

| Queen of Diamonds | Rachel (either biblical, historical (see Charles above), or mythical as a corruption of the Celtic Ragnel, relating to Lancelot below) |

| Queen of Clubs | Argine (possibly an anagram of regina, which is Latin for queen, or perhaps Argea, wife of Polybus and mother of Argus) |

| Knave of Spades | Ogier the Dane/Holger Danske (a knight of Charlemagne) |

| Knave of Hearts | La Hire (comrade-in-arms to Joan of Arc, and member of Charles VII's court) |

| Knave of Diamonds | Hector |

| Knave of Clubs | Judas Maccabeus, or Lancelot |

Later design changes

In early games the kings were always the highest card in their suit. However, as early as the late 14th century special significance began to be placed on the nominally lowest card, now called the Ace, so that it sometimes became the highest card and the Two, or Deuce, the lowest. This concept may have been hastened in the late 18th century by the French Revolution, where games began being played "ace high" as a symbol of lower classes rising in power above the royalty. The term "Ace" itself comes from a dicing term in Anglo-Norman language, which is itself derived from the Latin as (the smallest unit of coinage). Another dicing term, trey (3), sometimes shows up in playing card games.

Corner and edge indices enabled people to hold their cards close together in a fan with one hand (instead of the two hands previously used). For cards with Latin suits the first pack known is a deck printed by Infirerra and dated 1693 (International Playing Cards Society Journal 30-1 page 34), but were commonly used only at the end of 18th century. Indices in the Anglo-American deck were used from 1875, when the New York Consolidated Card Company patented the Squeezers, the first cards with indices that had a large diffusion. However, the first deck with this innovation was the Saladee's Patent, printed by Samuel Hart in 1864.

Before this time, the lowest court card in an English deck was officially termed the Knave, but its abbreviation ("Kn") was too similar to the King ("K") and thus this term did not translate well to indices. However, from the 1600s on the Knave had often been termed the Jack, a term borrowed from the English Renaissance card game All Fours where the Knave of trumps has this name. All Fours was considered a game of the lower classes, so the use of the term Jack at one time was considered vulgar. The use of indices, however, encouraged a formal change from Knave to Jack in English decks. In decks for non-English languages, this conflict does not exist; the French tarot deck for instance labels its lowest court card the "Valet", which is the "squire" to the Knight card (not seen in 52-card decks) as the Queen is paired with the King.

This was followed by the innovation of reversible court cards. This invention is attributed to a French card maker of Agen in 1745. But the French government, which controlled the design of playing cards, prohibited the printing of cards with this innovation. In central Europe (trappola cards), Italy (tarocchino bolognese) and in Spain the innovation was adopted during the second half of 18th century. In Great Britain the deck with reversible court cards was patented in 1799 by Edmund Ludlow and Ann Wilcox. The Anglo-American pack with this design was printed around 1802 by Thomas Wheeler. Reversible court cards meant that players would not be tempted to turn upside-down court cards right side up. Before this, other players could often get a hint of what other players' hands contained by watching them reverse their cards. This innovation required abandoning some of the design elements of the earlier full-length courts.

During the French Revolution, the traditional design of Kings, Queens, and Jacks became Liberties, Equalities, and Fraternities. The radical French government of 1793 and 1794 saw themselves as toppling the old regime and a good revolutionary would not play with Kings or Queens, but with the ideals of the revolution at hand. This would ultimately be reversed in 1805 with the rise of Napoleon.

The joker is an American invention. It was devised for the game of Euchre, which spread from Europe to America beginning shortly after the American Revolutionary War and was very popular by the mid-1800s. In Euchre, the highest trump card is the Jack of the trump suit, called the right bower; the second-highest trump, the left bower, is the Jack of the suit of the same color as trumps. The joker was invented c. 1870 as a third trump, the best bower, which ranked higher than the other two bowers. The name of the card is believed to derive from juker, a variant name for Euchre.

In the 19th century, a type of card known as a transformation playing card became popular in Europe and America. In these cards, an artist incorporated the pips of the non-face cards into an artistic design.

Symbolism

Popular legend holds that the composition of a deck of cards has religious, metaphysical, or astronomical significance.

Current status

See also: Suit (cards)Anglo-American

The primary deck of fifty-two playing cards in use today includes thirteen ranks of each of the four French suits, diamonds (♦), spades (♠), hearts (♥) and clubs (♣), with reversible Rouennais "court" or face cards (some modern face card designs, however, have done away with the traditional reversible figures). Each suit includes an ace, depicting a single symbol of its suit; a king, queen, and jack, each depicted with a symbol of its suit; and ranks two through ten, with each card depicting that many symbols (pips) of its suit. Two (sometimes one or four) jokers, often distinguishable with one being more colorful than the other but not belonging to any of the suits, are included in commercial decks but many games require one or both to be removed before play. Modern playing cards carry index labels on opposite corners (rarely, all four corners) to facilitate identifying the cards when they overlap and so that they appear identical for players on opposite sides.

The fancy design and manufacturer's logo commonly displayed on the Ace of Spades began under the reign of James I of England, who passed a law requiring an insignia on that card as proof of payment of a tax on local manufacture of cards. Until August 4, 1960, decks of playing cards printed and sold in the United Kingdom were liable for taxable duty and the Ace of Spades carried an indication of the name of the printer and the fact that taxation had been paid on the cards. The packs were also sealed with a government duty wrapper.

Though specific design elements of the court cards are rarely used in game play and many differ between designs, a few are notable. The Jack of Spades, Jack of Hearts, and King of Diamonds are drawn in profile, while the rest of the court are shown in full face; these cards are commonly called "one-eyed". When deciding which cards are to be made wild in some games, the phrase "acey, deucey, one-eyed jack" (or "deuces, aces, one-eyed faces") is sometimes used, which means that aces, twos, and the one-eyed jacks are all wild. The King of Hearts is the only King with no mustache, and is also typically shown with a sword behind his head, making him appear to be stabbing himself. This leads to the nickname "suicide king". However, it can also be perceived as though he is hiding the sword behind him. This and his missing moustache have led him to be named "The False King". The axe held by the King of Diamonds is behind his head with the blade facing toward him. He is traditionally armed with an axe while the other three kings are armed with swords, and thus the King of Diamonds is sometimes referred to as "the man with the axe" because of this. This is the basis of the trump "one-eyed jacks and the man with the axe". The Jack of Diamonds is sometimes known as "laughing boy". The Ace of Spades, unique in its large, ornate spade, is sometimes said to be the death card, and in some games is used as a trump card. The Queen of Spades usually holds a scepter and is sometimes known as "the bedpost queen", though more often she is called "Black Lady". In many decks, the Queen of Clubs holds a flower. She is thus known as the "flower Queen", (though in many playing cards from Germany and Sweden she is depicted with a fan) though this design element is among the most variable; the standard Bicycle Poker deck depicts all Queens with a flower styled according to their suit.

There are theories about who the court cards represent. For example, the Queen of Hearts is believed by some to be a representation of Elizabeth of York—the Queen consort of King Henry VII of England, or it is sometimes believed to be a representation of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII. The United States Playing Card Company suggests that, in the past, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne, the King of Diamonds was Julius Caesar, the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great, and the King of Spades was the Biblical King David (see King (playing card)). However, the Kings, Queens, and Jacks of standard Anglo-American cards today do not represent anyone in particular. They stem from designs produced in Rouen before 1516, and, by 1540–67, these Rouen designs show well executed pictures in the court cards with the typical court costumes of the time. In these early cards, the Jack of Spades, Jack of Hearts, and King of Diamonds are shown from the rear, with their heads turned back over the shoulder so that they are seen in profile; however, the Rouen cards were so badly copied in England that the current designs are gross distortions of the originals.

Other oddities such as the lack of a moustache on the King of Hearts also have little significance. The King of Hearts did originally have a moustache, but it was lost by poor copying of the original design. Similarly, the objects carried by the court cards have no significance. They merely differentiate one court card from another and have also become distorted over time.

The most common sizes for playing cards are poker size (2½in × 3½in; 63 mm × 88 mm, or B8 size according to ISO 216) and bridge size (2¼in × 3½in, approx. 56 mm × 88 mm), the latter being narrower, and thus more suitable for games such as bridge in which a large number of cards must be held concealed in a player's hand. Interestingly, in most casino poker games, the bridge-sized card is used; the use of less material means that a bridge deck is slightly cheaper to make, and a casino may use many thousands of decks per day so the minute per-deck savings add up. Other sizes are also available, such as a smaller size (usually 1¾in × 2⅝in, approx. 44 mm × 66 mm) for solitaire, tall narrow designs (usually 1¼in × 3in) for travel and larger ones for card tricks. The weight of an average B8-sized playing card is 0.063 oz (1.8g), a deck 3.3 oz (94g).

Some decks include additional design elements. Casino blackjack decks may include markings intended for a machine to check the ranks of cards, or shifts in rank location to allow a manual check via inlaid mirror. Many casino decks and solitaire decks have four indices instead of the usual two. Many decks have large indices, largely for use in stud poker games, where being able to read cards from a distance is a benefit and hand sizes are small. Some decks use four colors for the suits in order to make it easier to tell them apart: the most common set of colors is black (spades ♠), red (hearts ♥), blue (diamonds ♦) and green (clubs ♣). Another common color set is borrowed from the German suits and uses green Spades and yellow Diamonds (as the comparable German suits are Leaves and Bells respectively; see below) with red Hearts and black Clubs.

When giving the full written name of a specific card, the rank is given first followed by the suit, e.g., "Ace of Spades". Shorthand notation may list the rank first "A♠" (as is typical when discussing poker) or list the suit first (as is typical in listing several cards in bridge) "♠AKQ".

Tens may be either abbreviated to T or written as 10.

In the UK, the most commonly available pack of cards is Waddingtons Number 1, which comprises the 52 standard cards plus 4 others - 2 coloured jokers, a contract bridge scoring card and an advertisement card.

In poker and many other card games, 52 playing cards are used; 13 of each suit:

- clubs

- diamonds

- hearts

- spades

| Suit | Ace | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Jack | Queen | King |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clubs | |||||||||||||

| Diamonds | |||||||||||||

| Hearts | |||||||||||||

| Spades |

Piquet

The piquet deck is a subset of the French-suited 52-card deck, with all values from 2 through 6 in each suit removed. The resulting 32-card deck is notable for its use in a variety of games; a trick-taking game from the 1300s, Piquet, gave the deck its most common name, and the game of Belote, currently the most popular card game in France, also uses this deck. West German players adopted the deck for the game of Skat (the traditional Skat deck uses German suits; see below). Two of these decks are used in the game of Bezique.

Pinochle/Doppelkopf

The game of Pinochle, which evolved from the French game Bezique, uses a deck composed of two copies of each Anglo-American card with values from 9 through King and Ace. A deck with the same composition, but different card art, is available in Europe for the very popular German game of Doppelkopf, which derived from the game Sheepshead and is related to Skat.

Tarot

Main article: Tarot

The 78-card Tarot deck, and subsets of it, are used for a variety of European trick-taking games. The Tarot is distinguished from most other decks by the use of a separate trump suit of 21 cards, and one Fool, whose role varies according to the specific game. Additionally, it differs from the 52-card deck in the use of one additional court card in each suit, the Cavalier or Knight. In Europe, the deck is known primarily as a playing card deck; in the Americas, the deck is primarily known for its use in cartomancy; the trumps and fool comprising the Major Arcana while the 56 suited cards make up the Minor Arcana.

The origins of the tarot deck are thought to be Italian, with the oldest surviving examples dating from the mid 1400s in Milan, and using the traditional Latin suits of Swords, Cups, Coins and Staves (representing the four main classes of feudal society; military, clergy, mercantile trade, and agriculture). It is generally thought that the tarot was invented between 1411 and 1425 by adding trump cards to a deck format that was already popular in Italy as of this period, having been introduced from North Africa in the mid 1300s. The deck spread from Italy to Germanic countries, where the Latin suits evolved into the suits of Leaves (or Shields), Hearts (or Roses), Bells, and Acorns, and a combination of Latin and Germanic suit pictures and names resulted in the internationally recognized French suits of Spades, Hearts, Diamonds and Clubs. It was a simplification of this French-suited tarot deck by removing the trumps that resulted in the English deck, popularized by British colonization and the gentleman's game Brag. The English deck would eventually become the internationally recognized 52-card deck.

The trumps originally represented characters and ideals of increasing power, from the Magician and High Priestess of the 1 and 2 of trumps to the Sun, Judgement and the World at the high end. Allegorical meanings for each card existed as of the earliest days of the deck, but it wasn't until the late 1700s's that the works of Antoine Court de Gebelin made decks based on the Tarot de Marseille popular for divinatory purposes.

From this point, the evolution of decks for cartomancy and for gaming diverged; the "reading tarots" based on the symbolic designs of the Tarot de Marseille (which were modified slightly to produce the widely known Rider-Waite deck) kept the older style of full-length character art, specific character meanings for the 21 trumps, and the use of the Latin suits (although most of the reading tarots in use today derive from the French Tarot de Marseille). On the other hand, "playing tarots", especially those of France and the Germanic regions, had by the end of the 1800s evolved into a form more resembling the modern playing card deck, with corner indices and easily identifiable number and court cards. The use of the traditional characters cards for the trumps was largely discarded in favor of more whimsical scenes. The Tarot Nouveau is an example of the current style of playing tarot, though the artwork and design of this deck can be traced back to the 1890s. The Italian and Spanish Tarocchi decks, however, have largely kept the traditional character identifications of each trump, as well as the Latin suits, though these decks are used almost exclusively for gaming. Tarocco Bolognese and Tarocco Piedmontese are examples of Italian-suited playing tarot decks.

Sets consisting of 56 Tarot playing card have 14 cards of each suit

- clubs

- diamonds

- hearts

- spades

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Jack | Knight | Queen | King | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clubs: | ||||||||||||||

| Diamonds: | ||||||||||||||

| Hearts: | ||||||||||||||

| Spades: |

German

German suits may have different appearances. Many Eastern and Southern Germans prefer decks with Hearts, Bells, Leaves, and Acorns (for Hearts, Diamonds, Spades, and Clubs), as mentioned above. In the game Skat, East German players used the German deck, while players in Western Germany mainly used the French deck. After the reunification a compromise deck was created for official Skat tournaments, with French symbols but German colors (green Spades and yellow Diamonds).

Central European

The cards of Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Northern Croatia, Slovakia, Western Romania, Transcarpathia in Ukraine, Vojvodina in Serbia and South Tyrol use the same suits (Hearts, Bells, Leaves and Acorns) as the cards of Southern and Eastern Germany. They usually have a deck of 32 or 36 cards. The numbering includes VII, VIII, IX, X, Under, Over, King and Ace. Some variations with 36 cards have also the number VI. The VI in bells also has the function like a joker in some games and it is named Welli or Weli.

These cards are illustrated with a special picture series that was born in the times before the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, when revolutionary movements were awakening all over in Europe. The Aces show the four seasons: the Ace of Hearts is Spring, the Ace of Bells is Summer, the Ace of Leaves is Autumn and the Ace of Acorns is Winter. The characters of the Under and Over cards were taken from the drama William Tell, the legendary Swiss freedom fighter, written by Friedrich Schiller in 1804, which was shown at Kolozsvár in 1827. It was long believed that the card was invented in Vienna at the Card Painting Workshop of Ferdinand Piatnik, however in 1974 the very first deck was found in an English private collection, and it has shown the name of the inventor and creator of deck as József Schneider, a Master Card Painter at Pest, and the date of its creation as 1837. Had he not chosen the Swiss characters of Schiller's play, had he chosen Hungarian heroes or freedom fighters, his deck of cards would never have made it into distribution, due to the heavy censorship of the government at the time. Interestingly, although the characters on the cards are Swiss, these cards are unknown in Switzerland.

Games that are played with this deck in Hungary include Skat, Ulti, Snapszer (or 66), Zsír aka Víg a hetes (Grease or Sevens wild), Fire, Preferansz, Makaó, Lórum, Piros pacsi (Red paw) and Piros papucs (Red slipper). This set of cards is also used very often in the game of Preferans. In Croatia and Slovenia these cards are also commonly used for a game called Belot (also popular in Bulgaria and Armenia). Explanations of these games can be found at The Card Games Website.

In Czech republic these cards are called mariášky or mariášové karty (both means cards for mariáš), or sometimes pikety. The cards are used for almost all common card games in Czech lands, including the most famous mariáš, and very popular games like prší or Oko bere (slightly different Czech version of Blackjack).

The most common game played in Western Romania (Transylvania and Banat) is Cruce, a variation of Snapszer, most commonly played in 2 pairs, with team members facing each other, hence the name (Cruce = Romanian for Cross).

Russia

In Russia and many countries of the former USSR, the Russian 36-card deck is the most common one. Its numbering includes 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, Valet (Jack), Dama (Dame), Korol (King) and Tuz (Ace). The suits are identical to French ones. This deck is used for several Russian card games such as Durak or Ochko (a variant of Blackjack). Another common Russian deck is the Preferans deck that is used for the card game of the same name. It begins with sevens and is identical to the Piquet deck.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the national game is Jass. It is played with decks of 36 cards. West of the Brünig-Napf-Reuss line, a French-style 36-card deck is used, with numbers from 6 to 10, Jacks, Queens, Kings and Aces. The same kind of deck is used in Graubünden and in parts of Thurgau.

In Central Switzerland, Zürich, Schaffhausen and Eastern Switzerland, the prevalent deck consists of 36 playing cards with the following suits: Roses, Bells, Acorns and Shields (in German: Rosen, Schellen, Eichel und Schilten). The ranks of the alternate deck, from low to high, are: 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 ("Banner"), Unter (lower jack), Ober (higher jack), King and Ace.

Italian

Italian playing cards most commonly consist of a deck of 40 cards (4 suits going 1 to 7 plus 3 face cards), and are used for playing Italian regional games such as Scopa or Briscola. 52 (or more rarely 36) card sets are also found in the north. Since these cards first appeared in the late 14th century when each region in Italy was a separately ruled province, there is no official Italian pattern. There are sixteen official regional patterns in use in different parts of the country (about one per region). These sixteen patterns are split amongst four regions:

- Northern Italian Suits - Triestine, Trevigiane, Trentine, Primiera Bolognese, Bergamasche, Bresciane

- Spanish-like Suits - Napoletane, Sarde, Romagnole, Siciliane, Piacentine.

- French Suits - Genovesi, Lombarde or Milanesi, Toscane, Piemontesi.

- German Suits - Salisburghesi used in Alto Adige/Südtirol

The suits are coins (sometimes suns or sunbursts) (Denari in Italian), swords (Spade), cups (Coppe) and clubs (sometimes batons Bastoni), and each suit contains an ace (or one), numbers two through seven, and three face cards. The face cards are:

- Re (king), the highest valued — a man standing, wearing a crown

- Cavallo (lit. horse) - a man sitting on a horse / or Donna (lit. woman from Latin domina = mistress) - a standing woman with a crown

- Fante (lit. infantry soldier) - a younger figure standing, without a crown

The Spanish-like-suit knave (fante - the lowest face card) is depicted as a woman, and is sometimes referred to as donna like the next higher face card of the French-suit deck; this, when coupled with the French usage, which puts a queen, also called donna (woman) in Italian and not regina (queen), as the mid-valued face card, can very occasionally lead to a swap of the value of the French-suit donna (or more rarely of the international-card Queen) and the knave (or jack).

Unlike Anglo-American cards, some Italian cards do not have any numbers (or letters) identifying their value. The cards' value is determined by identifying the face card or counting the number of suit characters.

Spanish

The traditional Spanish deck (referred to as baraja española in Spanish) uses Latin suit symbols. Being a Latin-suited deck (like the Italian deck), it is organized into four palos (suits) that closely match those of the Italian-suited Tarot deck: oros ("golds" or coins), copas (beakers or cups), espadas (swords) and bastos (batons or clubs). Certain decks include two "comodines" (jokers) as well.

The cards (cartas in Spanish) are all numbered, but unlike in the standard Anglo-French deck, the card numbered 10 is the first of the court cards (instead of a card depicting ten coins/cups/swords/batons); so each suit has only twelve cards. The three court or face cards in each suit are as follows: la sota ("the knave" or jack, numbered 10 and equivalent to the Anglo-French card J), el caballo ("the horse", horseman, knight or cavalier, numbered 11 and used instead of the Anglo-French card Q; note the Tarot decks have both a queen and a knight of each suit, while the Anglo-French deck uses the former, and the Spanish deck uses the latter), and finally el rey ("the king", numbered 12 and equivalent to the Anglo-French card K). However, most Spanish games involve forty-card decks, with the 8s and 9s removed, similar to the standard Italian deck.

The box that goes around the figure has a mark to distinguish the suit without showing all of your cards: The cups have one interruption, the swords two, the clubs three, and the gold none. This mark is called "la pinta" and gave rise to the expression: "le conocí por la pinta" (I knew him by his markings).

The Baraja have been widely considered to be part of the occult in many Latin-American countries, yet they continue to be used widely for card games and gambling, especially in Spain, which does not use the Anglo-French deck. Among other places, the Baraja have appeared in One Hundred Years of Solitude and other Hispanic and Latin American literature. The Spanish deck is used not only in Spain, but also in other countries where Spain maintained an influence (e.g., Mexico, Argentina and most of Hispanic America, the Philippines and Puerto Rico) 1. Among the games played with this deck are: el mus (a very popular and highly regarded vying game of Basque origin), la brisca, la pocha, el tute (with many variations), el guiñote, la escoba del quince (a trick-taking game), el julepe, el cinquillo, las siete y media, la mona, el truc (or truco), el cuajo (a matching game from the Philippines), el jamón, el tonto, el hijoputa, el mentiroso, el cuco, las parejas and las cuarenta (a fishing game, the national card game of Ecuador).

In Spain, games of Anglo-American origin such as poker and blackjack are played with the international 52-card deck, which is called a baraja de poker.

East Asia

The standard 52-card deck is commonly known as a "poker" deck in Taiwan, Japan, China, and South Korea. Alternatively, a more common name in Japan and Korea for the same deck is trump (トランプ torampu, 트럼프 teureompeu respectively) which comes from the term trump card. These cards are most often used for baccarat and blackjack in casinos, or deciding the order of play or challenge in games of billiards. Poker itself and other western games are relatively unknown; however, there do exist East Asian games using the poker deck, such as Daifugo and Two-ten-jack. Home and online card games in east Asia such as Koi-Koi and Go-Stop use a Karuta, such as hanafuda, uta-garuta or kabufuda deck in Japan, and the equivalent hwatu deck in Korea.

Accessible playing cards

Playing cards have been adapted for use by the visually impaired by the inclusion of large-print and/or braille characters as part of the card. Both standard card decks and decks for specific games such as UNO are commonly adapted. Large-print cards are also commonly used by the elderly. In addition to increasing the size of the suit symbol and the denomination text, large-print cards commonly reduce the visual complexity of the images for simpler identification. They may also omit the patterns of pips in favor of one large pip to identify suit. Oversize cards are sometimes used but are uncommon. These can assist with ease of handling and to allow for larger text.

No universal standards for braille playing cards exist. There are many national and producer variations. In most cases each card is marked with two braille characters in the same location as the normal corner markings. The two characters can appear in either vertical (one character below another) or horizontal (two characters side by side). In either case one character identifies the card suit and the other the card denomination. 1 for ace, 2 through 9 for the numbered cards, X or the letter O for ten, J for jack, Q for queen, K for king. The suits are variously marked using D for diamond, S for spade, C or X for club and H or K for heart.

Symbols in Unicode

The Unicode standard defines 8 characters for card suits in the Miscellaneous Symbols block, from U+2660 to U+2667:

| U+2660 dec: 9824 | U+2661 dec: 9825 | U+2662 dec: 9826 | U+2663 dec: 9827 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ♠ | ♡ | ♢ | ♣ |

| BLACK SPADE SUIT | WHITE HEART SUIT | WHITE DIAMOND SUIT | BLACK CLUB SUIT |

| ♠ ♠ ♠ |

♡ ♡ |

♢ ♢ |

♣ ♣ ♣ |

| U+2664 dec: 9828 | U+2665 dec: 9829 | U+2666 dec: 9830 | U+2667 dec: 9831 |

| ♤ | ♥ | ♦ | ♧ |

| WHITE SPADE SUIT | BLACK HEART SUIT | BLACK DIAMOND SUIT | WHITE CLUB SUIT |

| ♤ ♤ |

♥ ♥ ♥ |

♦ ♦ ♦ |

♧ ♧ |

There is also a proposal by Michael Everson, dated 2004-05-18 to encode the 52 cards of the Anglo-American-French deck together with a character for "Playing Card Back" and another for a joker. This concept is included in the Unicode 6.0 draft specification.

Production techniques

The typical production process for a new deck starts with the choice between the most suitable material: card stock or plastic.

Cards are printed on unique sheets that undergo a varnishing procedure in order to enhance the brightness and glow of the colors printed on the cards, as well as to increase their durability.

In today’s market, some high-quality products are available. There are some specific treatments on card surfaces, such as calendering and linen finishing, that guarantee performance for either professional or domestic use.

The cards are printed on sheets, which are cut and arranged in bands (vertical stripes) before undergoing a cutting operation that cuts out the individual cards. After assembling the new decks, they pass through the corner-rounding process that will confer the final outline: the typical rectangular playing-card shape.

Finally, each deck is wrapped in cellophane, inserted in its case and is ready for the final distribution.

See also

|

References

- Explanatory notes

- Stamp Act 1765 imposed a tax on playing cards.

- Citations

- Needham 2004, p. 131–132

- Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- Needham 2004, p. 334 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- ^ Lo (2000), p. 390.

- ^ Needham 2004, p. 132

- Wilkinson 1895

- Singer, p. 4

- Donald Laycock in Skeptical—a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0731657942, p. 67

- Banzhaf, Hajo (1994), Il Grande Libro dei Tarocchi (in Italian), Roma: Hermes Edizioni, p. 16, ISBN 8-8793-8047-8

{{citation}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Mayer, Leo Ary (1939), Le Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, vol. 38, pp. 113–118, retrieved 2008-09-08.

- International Playing Cards Society Journal, 30-3, page 139

- Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p.135. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0684801647.

- Early Card painters and Printers in Germany, Austria and Flandern (14th and 15th century)

- International Playing Cards Society Journal XXVII-5 p. 186 and International Playing Cards Society Journal 31-1 p. 22

- US Playing Card Co. - A Brief History of Playing Cards (archive.org mirror)

- Beal, George. Playing cards and their story. 1975. New York: Arco Publishing Comoany Inc. p. 58

- Games « A cache of random trivia

- Andy's Playing Cards - Shapes, Sizes and Colors

- Unicode 6.0.0, retrieved 2010-07-23

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Playing card" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Bibliography

- Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking British Museum Press (in UK),2nd edn, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Hind, Arthur M. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- Lo, Andrew. "The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2000): 389-406.

- Needham, Joseph (2004), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521058023

- Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-214165-1

- Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library MS Add. 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352

- Singer, Samuel Weller (1816), Researches into the History of Playing Cards, R. Triphook

- Wilkinson, W.H. (1895), "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards", The American Anthropologist, VIII: 61–78, doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070

External links

- History of the design of the court cards

- Online database of playing cards and card games

- Courts on playing cards

- Deck of playing cards in SVG

- Deck of playing cards in .fla and .png

- The History of Playing Cards discussed in 1987 by Roger Somerville

- World Web Playing Cards Museum

- Regional Patterns of 18th Century France

| Occult tarot | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occultists | |||||||||

| Major Arcana numbered cards |

| ||||||||

| Minor Arcana suit cards |

| ||||||||

| Decks | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||