| Revision as of 08:49, 22 August 2010 editPetri Krohn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users37,094 edits currently seizing property and other assets← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:02, 25 August 2010 edit undoEnkyo2 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers58,409 editsm inline citationsNext edit → | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

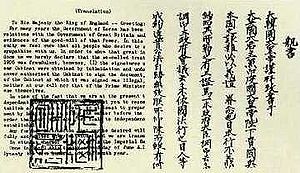

| The '''Eulsa Treaty''' or '''Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty''' was made between the ] and the ] on 17 November 1905, influenced by the result of the ]. This treaty deprived ] of its diplomatic sovereignty,<ref name="KimKoo"> | The '''Eulsa Treaty''' or '''Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty''' was made between the ] and the ] on 17 November 1905, influenced by the result of the ].<ref>Clare, Israel ''et al.'' (1910). {{Google books|02cmAQAAIAAJ|''Library of universal history and popular science,'' p. 4732.|page=4732}}</ref> This treaty deprived ] of its diplomatic sovereignty,<ref name="KimKoo"> | ||

| {{cite web | {{cite web | ||

| |url=http://www.ivynews.kr/news/news_main.html?number=41&code=feature | |url=http://www.ivynews.kr/news/news_main.html?number=41&code=feature | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| Following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, with its subsequent withdrawal of Russian influence, and the ], by which the ] agreed not to interfere with Japan in matters concerning Korea, the Japanese government sought to formalize its ] over the ]. | Following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, with its subsequent withdrawal of Russian influence, and the ], by which the ] agreed not to interfere with Japan in matters concerning Korea, the Japanese government sought to formalize its ] over the ]. | ||

| Delegates of both Empires met in ] to resolve differences in matters pertaining to Korea’s future foreign policy; however, with the Korean Imperial palace under occupation by Japanese troops, and the ] stationed at strategic locations throughout Korea, the Korean side was at a distinct disadvantage in the discussions. On 17 November 1905, the Korean cabinet signed an agreement that had been prepared by ] in the Jungmyeongjeon Hall, a European-style building that was once part of ]<ref name="deoksu"/>. The Agreement gave Japan complete responsibility for Korea’s foreign affairs, and placed all trade through Korean ports under Japanese supervision. | Delegates of both Empires met in ] to resolve differences in matters pertaining to Korea’s future foreign policy; however, with the Korean Imperial palace under occupation by Japanese troops, and the ] stationed at strategic locations throughout Korea, the Korean side was at a distinct disadvantage in the discussions. On 17 November 1905, the Korean cabinet signed an agreement that had been prepared by ] in the Jungmyeongjeon Hall, a European-style building that was once part of ]<ref name="deoksu"/>. The Agreement gave Japan complete responsibility for Korea’s foreign affairs,<ref>Carnegie Endowment (1921). {{Google books|DtcBAAAAYAAJ|Pamphlet 43: ''Korea, Treaties and Agreements," p. vii.|page=vii}}</ref> and placed all trade through Korean ports under Japanese supervision. | ||

| The treaty was enacted after it received the signature of five Korean ministers; (who have been reviled by later Korean historians as the '']''): | The treaty was enacted after it received the signature of five Korean ministers; (who have been reviled by later Korean historians as the '']''): | ||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

| This protest, the lack of the Imperial assent, and the intimidation by Japanese troops during the negotiations have been used by later historians and lawyers to question the legal validity of the treaty,{{Citation needed|date=August 2010}} as being signed under duress, though the treaty remained uncontested internationally until ] in ]. | This protest, the lack of the Imperial assent, and the intimidation by Japanese troops during the negotiations have been used by later historians and lawyers to question the legal validity of the treaty,{{Citation needed|date=August 2010}} as being signed under duress, though the treaty remained uncontested internationally until ] in ]. | ||

| This treaty laid the foundation for the ] in and subsequent ] in 1910. | This treaty laid the foundation for the ] in and subsequent ] in 1910.<u>Inline citation format</u>. <ref>United States. Dept. of State. (1919). {{Google books|35QpAAAAYAAJ|''Catalogue of treaties: 1814-1918,''p. 273.|page=273}}</ref> | ||

| The Eulsa Treaty and the subsequent ] between Korea and Japan were mutually declared ''"already null and void"'' explicitly by the ] of 1965. | The Eulsa Treaty and the subsequent ] between Korea and Japan were mutually declared ''"already null and void"'' explicitly by the ] of 1965. | ||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

| | isbn = 0198221681 | | isbn = 0198221681 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| * Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of International Law. (1921). Pamphlet 43: ''Korea, Treaties and Agreements." The Endowment: Washington, D.C. | |||

| * Clare, Israel Smith; Hubert Howe Bancroft and George Edwin Rines. (1910). ''Library of universal history and popular science.'' New York: The Bancroft society. | |||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| | last = Duus | | last = Duus | ||

| Line 129: | Line 131: | ||

| | isbn = 0520213610 | | isbn = 0520213610 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| * United States. Dept. of State. (1919). ''Catalogue of treaties: 1814-1918.'' Washington: Goverment Printing Office. | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 02:02, 25 August 2010

| Eulsa Treaty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 을사 조약 | ||||||

| Hanja | 乙巳條約 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 第二次日韓協約 | ||||||

| Hiragana | だいにじにっかんきょうやく | ||||||

The Eulsa Treaty or Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty was made between the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire on 17 November 1905, influenced by the result of the Russo-Japanese War. This treaty deprived Korea of its diplomatic sovereignty, in effect making Korea a protectorate of Japan. Later, in 1910, full annexation of Korea by Japan followed.

This treaty, later, was confirmed to be "already null and void" by Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea concluded in 1965.

History

Following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, with its subsequent withdrawal of Russian influence, and the Taft-Katsura Agreement, by which the United States agreed not to interfere with Japan in matters concerning Korea, the Japanese government sought to formalize its sphere of influence over the Korean peninsula.

Delegates of both Empires met in Seoul to resolve differences in matters pertaining to Korea’s future foreign policy; however, with the Korean Imperial palace under occupation by Japanese troops, and the Imperial Japanese Army stationed at strategic locations throughout Korea, the Korean side was at a distinct disadvantage in the discussions. On 17 November 1905, the Korean cabinet signed an agreement that had been prepared by Ito Hirobumi in the Jungmyeongjeon Hall, a European-style building that was once part of Deoksu Palace. The Agreement gave Japan complete responsibility for Korea’s foreign affairs, and placed all trade through Korean ports under Japanese supervision.

The treaty was enacted after it received the signature of five Korean ministers; (who have been reviled by later Korean historians as the Five Eulsa Traitors):

- Minister of Education Lee Wan-Yong (이완용;李完用)

- Minister of Army Yi Geun-taek (이근택;李根澤)

- Minister of Interior Yi Ji-yong (이지용;李址鎔)

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Pak Je-sun (박제순;朴齊純)

- Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry Gwon Jung-hyeon (권중현;權重顯)

Some officials, including most notably Emperor Gojong of Korea, did not sign the treaty, which had led Korean historians to dispute the de jure legality of the treaty. The officials included:

- Emperor Gojong

- Prime Minister Han Gyu-seol (한규설;韓圭卨)

- Minister of Justice Yi Ha-yeong (이하영;李夏榮)

- Minister of Finance Min Yeong-gi (민영기;閔泳綺)

Nevertheless, it took effect immediately.

Gojong sent personal letters to major powers to appeal for their support against the illegal signing. As of February 21, 2008, 17 of which bearing his imperial seal have been confirmed sent by Gojong, including 7 of which are:

- United Kingdom

- France

- Russia

- Austria-Hungary

- Italy

- Belgium

- Qing China

- Germany which was personally handwritten by Gojong

Afterwards, in 1907, Korean Emperor Gojong sent three secret emissaries to the second international Hague Peace Convention to protest the unfairness of the Eulsa Treaty. But the great powers of the world refused to allow Korea to take part in this conference.

Not only the Emperor but the other Koreans protested against the Treaty. Jo Byeong-se and Min Yeong-hwan, who were high officials and led resistance against Eulsa treaty, killed themselves as resistance. Local yangbans and commoners joined righteous armies. They were called "Eulsa Euibyeong" (을사의병, 乙巳義兵) meaning "Righteous army against Eulsa Treaty"

This protest, the lack of the Imperial assent, and the intimidation by Japanese troops during the negotiations have been used by later historians and lawyers to question the legal validity of the treaty, as being signed under duress, though the treaty remained uncontested internationally until Japan's defeat in World War II.

This treaty laid the foundation for the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1907 in and subsequent annexation of Korea in 1910.Inline citation format.

The Eulsa Treaty and the subsequent unequal treaties between Korea and Japan were mutually declared "already null and void" explicitly by the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea of 1965.

In a joint statement on 23 June 2005, officials of South Korea and North Korea reiterated their stance that the Eulsa treaty be null and void on a claim of coercion by the Japanese.

South Korea is currently seizing property and other assets from the descendants of people who have identified as Japanese collaborators at the time of the treaty.

Name

In the Korean calendar, eulsa is the Sexagenary Cycle's 42nd year in which the treaty was signed.

In Japanese, the treaty is known under several names including Second Japan-Korean Convention (第二次日韓協約, Dai-niji Nikkan Kyōyaku), Isshi Hogo Jōyaku (乙巳保護条約) and Kankoku Hogo Jōyaku (韓国保護条約).

See also

- Unequal Treaties

- History of Korea

- History of Japan

- Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty

- Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty of 1907

- List of Korea-related topics

- Liancourt Rocks

References

- Clare, Israel et al. (1910). Library of universal history and popular science, p. 4732., p. 4732, at Google Books

- "Independence leader Kim Koo". 2008-04-28. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ "Emperor Gojong's letter to German Kaiser discovered". 2008-02-21. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ "Deoksu Jungmyeongjeon". 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- The history of Korea, pp.461~462, by Homer Hulbert

- "Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea". It is confirmed that all treaties or agreements concluded between the Empire of Japan and the Empire of Korea on or before August 22, 1910 are already null and void.

- Carnegie Endowment (1921). Pamphlet 43: Korea, Treaties and Agreements," p. vii., p. vii, at Google Books

- "Emperor Gojong's Letter to German Kaiser Unearthed". 2008-06-21. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- United States. Dept. of State. (1919). Catalogue of treaties: 1814-1918,p. 273., p. 273, at Google Books

- Julian Ryall (14 July 2010). "South Korea targets Japanese collaborators' descendants". telegraph.co.uk.

Sources

- Beasley, W.G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198221681.

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of International Law. (1921). Pamphlet 43: Korea, Treaties and Agreements." The Endowment: Washington, D.C. OCLC 1644278

- Clare, Israel Smith; Hubert Howe Bancroft and George Edwin Rines. (1910). Library of universal history and popular science. New York: The Bancroft society. OCLC 20843036

- Duus, Peter (1998). The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895-1910. University of California Press. ISBN 0520213610.

- United States. Dept. of State. (1919). Catalogue of treaties: 1814-1918. Washington: Goverment Printing Office. OCLC 3830508