| Revision as of 11:45, 3 September 2010 edit79.154.22.3 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:51, 3 September 2010 edit undoAkerbeltz (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,778 edits Undid revision 382655866 by 79.154.22.3 (talk) rvvNext edit → | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| | shield_alt = Coat-of-arms of Biscay | | shield_alt = Coat-of-arms of Biscay | ||

| | motto = | | motto = | ||

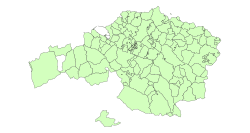

| | image_map = Localización |

| image_map = Localización provincia de Vizcaya.png | ||

| | mapsize = | | mapsize = | ||

| | map_alt = | | map_alt = | ||

Revision as of 11:51, 3 September 2010

For other uses, see Biscay (disambiguation). Province in Basque Country, Spain| Biscay Bizkaia | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

Flag Flag Coat of arms Coat of arms | |

| |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Community | |

| Capital | Bilbao |

| Government | |

| • Deputy General | José Luis Bilbao (EAJ) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,217 km (856 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,152,658 |

| • Density | 520/km (1,300/sq mi) |

| • Ranked | 9 |

| • Percent | 2.47% |

| Demonym | |

| Official languages | Basque, Spanish |

| Parliament | Cortes Generales |

| Congress seats | 8 |

| Senate seats | 4 |

| Juntas Generales de Vizcaya | 51 |

| Website | Bizkaiko Foru Aldundia |

Biscay (Template:Lang-eu (official), Template:Lang-es) is a province of the Basque Country in Spain. Its capital and largest city is Bilbao.

Etymology

It is nowadays accepted in linguistics (Koldo Mitxelena, etc.) that Bizkaia, the original Basque term, is a cognate of bizkar (cf. Biscarrosse in Aquitaine), with both place-name variants well attested in the whole Basque Country and out meaning 'low ridge' or 'prominence' (Iheldo bizchaya attested in 1141 for the hill Igeldo in Donostia).

Population

Of the 1,133,444 people who live in Biscay, about 35% live in the capital, Bilbao and 88% in its metropolitan area. Population density is 512.34 /km². Gernika, a town regarded as the spiritual centre of the traditional Basque Country, is located in Biscay.

Other important towns include Barakaldo, Getxo, Portugalete, Durango, Basauri, Galdakao and Balmaseda. This province has 111 municipalities. See List of municipalities in Biscay.

Biscayan is a dialect of the Basque language extending over the territory's eastern and central area up to Bilbao, while it may have lost ground to Spanish on most of the westerly strip of Encartaciones centuries ago.

Geography

Biscay is bordered by the provinces of Cantabria and Burgos to the west, Gipuzkoa to the east, and Álava to the south, and by the Cantabrian Sea (Bay of Biscay) to the north. Orduña (Urduña) is a Biscayan exclave located between Alava and Burgos provinces.

Climate

The climate is oceanic, with high precipitation all year round and moderate temperatures, which allow the lush vegetation to grow. Temperatures are more extreme in the higher lands of inner Biscay, where snow is more common during winter.

Features

The main features of the province are:

- The southern high mountain ranges, part of the Basque mountains, that form a continuous barrier with passes not lower than 600 m AMSL, forming the water divide of the Atlantic and Mediterranean bassins. These ranges are divided from west to east in Ordunte (Zalama, 1390 m), Salbada (1100 m), Gorbea (1481 m) and Urkiola (Anboto, 1331 m).

- The middle section which is occupied by the main river's valleys: Nervion, Ibaizabal and Kadagua. Kadagua runs west to east from Ordunte, Nervion south to north from Orduña and Ibaizabal east to west from Urkiola. Arratia river runs northwards from Gorbea and joins Ibaizabal. Each valley is separated by medium mountains like Ganekogorta (998m). Other mountains , like Oiz, separate the main valleys from the northern valleys. The northern rivers are: Artibai, Lea, Oka and Butron.

- The coast: the main features are the estuary of Bilbao where the main rivers meet the sea and the estuary of Gernika (Urdaibai). The coast is usually high, with cliffs and small inlets and coves.

(Click for full legend).

Sub-regions of Biscay

Historical merindades/eskualdeak

(numbers make reference to the map on the right)

Constituent ones: Incorporated later:- Durango

- Enkarterriak (Encartaciones) (8a and 8b)

- Orozko (9)

- Several chartered towns (blue/green dots)

- The city of (Urduina)

Modern subregions

- Greater Bilbao, divided in:

- Bilbao

- Ezkerraldea (left bank)

- Uribe-Kosta(right bank)

- Txorierri

- Alto Nervión

- Mungialdea (Uribe)

- Enkarterriak (Encartaciones)

- Busturialdea

- Durangaldea (Duranguesado)

- Lea-Artibai

- Arratia-Nerbioi

History

Biscay has been inhabited since the Middle Paleolithic, as attested by the archaeological remains and cave paintings found in its many caves. The Roman presence had little impact in the region and the Basque language and traditions have survived to this day.

Biscay itself appears in the Middle Ages, as a dependency of the kingdom of Pampelune (XI cent.) that became autonomous and finally a part of the Crown of Castile. The first mention of the name Biscay is appearing in a donation act to the monastery of Bickaga, located on the ria of Mundaka. According to Anton Erkoreka, the Vikings had a commercial base there from which they were expelled by 825. The ria of Mundaka is a easiest way to the river Ebro and at the end of it, the mediterranean trade.

In the modern age, the province became a major commercial and industrial area. Its prime harbour of Bilbao soon became the main Castilian gateway to Europe. Later, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the abundance of prime quality iron ore and the lack of feudal castes because of the local laborers standing up for their rights , favored rapid industrialization.

Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic

The first evidence of human dwellings (Neanderthal people) in Biscay happens in this period of prehistory. Mousterian artifacts have been found in three sites in Biscay: Benta Laperra (Karrantza), Kurtzia (Getxo) and Murua (Durangoaldea).

Late Paleolithic

- Chatelperronian culture (normally associated with Neanderthals as well) can be found in Santimamiñe cave (Busturialdea).

Most important settlements by modern humans (H. sapiens) can be considered the following:

- Aurignacian culture: Benta Laperra, Kurztia, and Lumentxa (Lekeitio)

- Gravettian culture: Santimamiñe, Bolinkoba (Durangoaldea) and Atxurra (Markina)

- Solutrean culture: Santimamiñe and Bolinkoba

- Magdalenian culture: Santimamiñe and Lumentxa

Paleolithic art is also present. Benta Laperra cave shows the oldest paintings, maybe from the Aurignacian or Solutrean period. Bison and bear are the animals depicted, together with abstract signs. From later periods (Magdalenian) are the murals of Arenaza (Sodupe) and Santimamiñe. In Arenaza female deers are the dominant motive, Santimamiñe shows bisons, horses, goats and deers.

Epi-paleolithic

This period (also called Mesolithic sometimes) is dominated in Biscay by the Azilian culture. Tools become smaller and more refined and, while hunting remains, fishing and seafood gathering become more important, finding now clear evidence of wild fruits too. Again Santimamiñe is one of the most important sites of this period. Others are Arenaza, Atxeta (not far from Santimamiñe), Lumentxa and nearby Urtiaga and Santa Catalina, together with Bolinkoba and neighbour Silibranka.

Neolithic

While the first evidences of Neolithic contact in the Basque Country can be dated to the 4th millennium BCE, it will be not until the beginning of the 3rd one that the area accepts, gradually and without radical changes, the agricultural and specially shepherding advances. Biscay is not particularly affected by this change and only three sites can be mentioned for this period: Arenaza, Santimamiñe and Kobeaga (Ea) and the advances adopted seem limited initially to sheep, domestic goats and very scarce pottery.

Together with Neolithic technologies, Megalithism also arrives. It will be the most common form of burial (simple dolmen) until c. 1500 BCE.

Chalcolithic and Bronze Age

While open air settlement starts to become something common as population grows, caves and natural shelters are still used in Biscay in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. Hunting becomes gradually a less important source of meat, replaced by sheep, goats and some bovine cattle. Metallic tools become more common but stone-made ones are also used.

Pottery types shows great continuity (not decorated) until the bell beaker makes its appearance.

The sites of this period now cover all the territory of Biscay, many being open air settlements, but the most important caves of the Paleolithic are still in use as well.

Iron Age

Very few sites have been identified for this period. Caves are abandoned for the most part but they still give some remains. The main caves of prehistory (Arenaza, Santimamiñe, Lumentxa) were still inhabited.

Roman period

Roman geographers have let us know that the territory of what is now Biscay dwelt two tribes: Caristii and Autrigones. The Caristii dwelt in nuclear Biscay, east of the firth of Bilbao, extending also into Northern Araba and some areas of Gipuzkoa, up to the river Deba. The Autrigones dwelt in the westernmost part of Biscay and Araba, extending also into the provinces of Cantabria, Burgos and La Rioja. Based in toponimy, historical and archaeological evidence, it is thought that these tribes spoke Basque language . The borders of the Biscayan dialect of Basque seem to be exactly those of the Caristian territory, exception made of the areas that have lost the old language.

There is no indication to resistance to Roman occupation in all the Basque area (excepting Aquitaine) until the late feudalizing period. Roman sources mention several towns in the area, Flaviobriga and Portus Amanus, though they have not been located. The site of Forua, near Gernika, has yielded archaeological evidence of Roman presence .

In the late Roman period, together with the rest of the Basque Country, it seems to have revolted against Roman domination and the process of feudalization.

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, the history of Biscay cannot be separated from that of the Basque Country as whole, being de facto independent although Visigoths and Franks attempted once and again to stabilish their domination.

In 905, Leonese chronicles mention for the first time the extension of the Kingdom of Pamplona as including all the western Basque provinces, as well as La Rioja and the nuclear Aragon. The territories that later would constitute Biscay was then part of that state.

In the conflicts that the newly sovereign Kingdom of Castile and Pamplona/Navarre had in the 11th and 12th century, the Castilians were supported by many landowners from La Rioja, who sought to consolidate their holdings under Castilian feudal law. These pro-Castilian lords were led by the house of Haro, who were eventually granted the rule of newly created Biscay, initially made up of the valleys of Uribe, Busturia, Markina, Zornotza and Arratia, plus several towns and the city of Urduina. It is unclear when this happened exactly but it is claimed that Iñigo López was the first one to be granted the title of Lord of Biscay in 1043.

Yet, as the western territories were soon reincorporated to Navarre, the actual constitution of Biscay as Lordship could not be consolidated before the Castilian invasion 1199-1200.

The title is inherited by Iñigo López's descendants until, by inheritance, in 1370 falls in the Infant John I of Castile, and passes to be one of the titles of the king of Castile, remaining since then connected with the crown, first to that of Castile and then, from Carlos I, to that of Spain, always with the condition that the Lord swore to defend and to maintain the fuero (Biscayan law, derived from Navarrese right) that affirmed that the possessors of the sovereignty of the Lordship were the own biscayans and that, at least in theory, they could refute the Lord.

The Lords and later the kings, came to swear the Statutes to the oak of Gernika, where the assembly of the Lordship was reunited.

Modern age

In the modern ages commerce on took great importance, specially for the Port of Bilbao, to which the kings granted privileges on trade with the ports of the Spanish Empire in 1511. Bilbao was already then the main Castilian harbour, from where wool was shipped to Flanders and other goods were imported.

In 1628, the separate territory of Durango was incorporated to Biscay. In the same century the so-called chartered municipalities west of Biscay were also incorporated in different dates, becoming another subdivision of Biscay: Encartaciones (Enkarterriak).

The coastal towns had a sizeable fleet of their own, mostly dedicated to fishing and trade. Along with other Basque towns of Gipuzkoa and Labourd, they were largely responsible for the partial extinction of North Atlantic Right Whales in the Bay of Biscay and of the first unstable settlement by Europeans in Newfoundland. They also were able to sign separate treaties with other powers, particularly England.

After the Napoleonic wars, Biscay, along with the other Basque provinces were threatened to have their self-rule cut by the now Liberal Spanish Cortes. This caused the successive Carlist Wars, where the Biscayan government, along with the other Basque provinces supported the reactionary faction.

Many of the towns though, notably Bilbao, were aligned with the Liberal government of Madrid. In the end the wars resulted in successive cuts of the wide autonomy of Biscay and the other provinces. In the 1850s extensive prime quality iron resources were discovered in Biscay. This brought a lot of foreign investment mainly from England and France, which made it one of Spain's richest and most industrialized provinces. Together with the industrialisation appeared important bourgeois families such as Ybarra, Chávarri and Lezama-Leguizamón. The great industrial (Iberdrola, Altos Hornos de Vizcaya) and financial (Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria- BBVA) groups were created.

Twentieth century

During the Second Spanish Republic, the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) governed the province. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, Biscay supported the Republican side against the army of Francisco Franco, of fascist ideology.

Soon after, the Republic acknowledged a statute of autonomy for the Basque Country but, due to fascist control of large parts of it, the first short-lived Basque Autonomous Community had power only over Biscay and a few nearby villages.

As the fascist army advanced westward from Navarre, defenses were planned and erected around Bilbao, called the Iron Belt. But the engineer in charge, José Goicoechea, defected to the fascists, causing the unfinished defenses to be of little value. In 1937, German airplanes under Franco's control destroyed the historic city of Gernika, not before having bombed Durango with some less severity few weeks before. Some months later, Bilbao fell to the fascists. The Basque army (Eusko Gudarostea) retreated to Santoña, beyond the limits of Biscay. There they pacted their surrender with the Italian forces (Santoña Agreement), but these gave them away to Franco. This surrender was seen negatively by the rest of Republican forces, who felt that the Basques had betrayed them.

Under the dictatorship of Franco, Biscay and Gipuzkoa (exclusively) were declared "traitor provinces" and stripped from any sort of self-rule.

Only after Franco's death in 1975, democracy was restored in Spain. The 1978 constitution, accepted the particular Basque laws (fueros) In 1979 the Statute of Guernica was approved and Biscay, Araba and Gipuzkoa formed the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country. The Autonomous Community of the Basque Country has its own parliament.

For all of the recent democratic period the winner of all the elections held in Biscay has been the Basque Nationalist Party. Recently the foral law was amended to extend it to the towns and the city of Urduina, that had always used the general Spanish Civil law.

References

- Michelena, Luis (1997). Apellidos Vascos. Donostia: Editorial Txertoa. pp. 75–76. ISBN 84-7148-008-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Toponimia: Bizkaia", Noticias de Gipuzkoa, pp. "Ortzadar", 08, 2010-05-08, retrieved 2010-05-08

- Anton Erkoreka, "Los Vikingos en Euskal Herria" Bilbao, 1995

External links

- Official website

- Señores de Vizcaya: list of all claimed Lords of Biscay and interesting historical maps.

| Traditional provinces of the Basque Country | ||

|---|---|---|

| Southern Basque Country | ||

| Northern Basque Country | ||

Categories: