| Revision as of 00:33, 19 March 2006 editObli (talk | contribs)6,489 editsm →Notes: I just like to make the ref/notes sections smaller, they're not really the focus of attention← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:46, 19 March 2006 edit undoBishonen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators80,276 edits →S. A. Andrée's scheme: minitweakNext edit → | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| The second half of the 19th century has often been called the heroic age of ].<ref>For instance in the title of John Maxtone-Graham's popularized narrative ''Safe Return Doubtful: The Heroic Age of Polar Exploration'', which has a chapter on the Andrée expedition.</ref> The inhospitable and dangerous ] and ] regions spoke powerfully to the ] imagination, not as lands with their own ] and (in the case of the Arctic) cultures, but as challenges to technological ingenuity and manly daring. | The second half of the 19th century has often been called the heroic age of ].<ref>For instance in the title of John Maxtone-Graham's popularized narrative ''Safe Return Doubtful: The Heroic Age of Polar Exploration'', which has a chapter on the Andrée expedition.</ref> The inhospitable and dangerous ] and ] regions spoke powerfully to the ] imagination, not as lands with their own ] and (in the case of the Arctic) cultures, but as challenges to technological ingenuity and manly daring. | ||

| The Swede S. A. Andrée shared these enthusiasms, and proposed a plan for letting the wind propel a ] ] from ] across the ] to the ], to fetch up in either Alaska, Canada, or Russia, and passing near or even right over the North Pole on the way. Andrée was an ] at the ] bureau in Stockholm, with a passion for ballooning. In 1893 he bought his own balloon, the ''Svea'', and made altogether nine journeys with her, starting from ] or ] and travelling a combined distance of 1,500 kilometres (930 mi).<ref>The most complete account of the ''Svea'' voyages is at .</ref> In the prevailing westerly winds, the ''Svea'' flights had a strong tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to the ] and drag his basket perilously along the surface of the water and/or slam it into the many islets in the ] (see artist's impression, right, of Andrée being blown off an island, from the evening paper '']''). On one occasion he was blown clear across the Baltic to ]. His longest trip was from Göteborg due east, across the breadth of Sweden and out over the Baltic to ]. Even though he actually saw a ] and heard breakers off ], he remained convinced that he was travelling over land and merely seeing lakes. | The Swede S. A. Andrée shared these enthusiasms, and proposed a plan for letting the wind propel a ] ] from ] across the ] to the ], to fetch up in either Alaska, Canada, or Russia, and passing near or even right over the North Pole on the way. Andrée was an ] at the ] bureau in Stockholm, with a passion for ballooning. In 1893 he bought his own balloon, the ''Svea'', and made altogether nine journeys with her, starting from ] or ] and travelling a combined distance of 1,500 kilometres (930 mi).<ref>The most complete account of the ''Svea'' voyages is at .</ref> In the prevailing westerly winds, the ''Svea'' flights had a strong tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to the ] and drag his basket perilously along the surface of the water and/or slam it into one of the many rocky islets in the ] (see artist's impression, right, of Andrée being blown off an island, from the evening paper '']''). On one occasion he was blown clear across the Baltic to ]. His longest trip was from Göteborg due east, across the breadth of Sweden and out over the Baltic to ]. Even though he actually saw a ] and heard breakers off ], he remained convinced that he was travelling over land and merely seeing lakes. | ||

| The main purpose of Andrée's ''Svea'' flights was to test and perfect the drag rope steering technique which he had invented and wanted to use on his projected North Pole expedition. Drag ropes, which hang from the balloon basket and drag part of their length on the ground, are designed to counteract the tendency of ] craft to travel at the same speed as the wind, a situation that makes steering by ]s impossible. The friction of the ropes was intended to slow the balloon to the point where the sails would have an effect (beyond that of making the balloon rotate on its ]). Andrée claimed that, with the drag rope/sails steering, his ''Svea'' had essentially become a ], but this notion is rejected by modern balloonists. The Swedish Ballooning Association ascribes Andrée's conviction entirely to wishful thinking, capricious winds, and the fact that much of the time Andrée was inside clouds and had little idea where he was or which way he was moving.<ref>.</ref> Persistently, too, his drag ropes would snap, fall off, become entangled in one another, or get stuck to the ground, which could result in pulling the often low-flying balloon down into a dangerous bounce. No modern Andrée researcher has expressed any faith in drag ropes as a balloon steering technique. | The main purpose of Andrée's ''Svea'' flights was to test and perfect the drag rope steering technique which he had invented and wanted to use on his projected North Pole expedition. Drag ropes, which hang from the balloon basket and drag part of their length on the ground, are designed to counteract the tendency of ] craft to travel at the same speed as the wind, a situation that makes steering by ]s impossible. The friction of the ropes was intended to slow the balloon to the point where the sails would have an effect (beyond that of making the balloon rotate on its ]). Andrée claimed that, with the drag rope/sails steering, his ''Svea'' had essentially become a ], but this notion is rejected by modern balloonists. The Swedish Ballooning Association ascribes Andrée's conviction entirely to wishful thinking, capricious winds, and the fact that much of the time Andrée was inside clouds and had little idea where he was or which way he was moving.<ref>.</ref> Persistently, too, his drag ropes would snap, fall off, become entangled in one another, or get stuck to the ground, which could result in pulling the often low-flying balloon down into a dangerous bounce. No modern Andrée researcher has expressed any faith in drag ropes as a balloon steering technique. | ||

Revision as of 01:46, 19 March 2006

S. A. Andrée's Arctic balloon expedition of 1897 was an ill-fated effort to reach the North Pole, in which all three expedition members perished. S. A. Andrée (1854–1897), a Swedish patent bureau engineer and ballooning enthusiast, proposed a voyage by hydrogen balloon from Svalbard to either Russia or Canada, passing, with luck, straight over the North Pole on the way. The scheme was received with patriotic enthusiasm in Sweden, a northern nation which had fallen behind in the race for the North Pole.

Andrée neglected many early signs of the dangers of his balloon plan. Being able to steer the balloon to some extent was essential for a safe journey, and there was plenty of evidence that the drag-rope steering technique he had himself invented was ineffective; yet he staked the fate of the expedition on drag ropes. Worse, the polar balloon Eagle was delivered directly from its Paris maker to Svalbard without previous tryout, and when measurements there showed it to be losing 68 kilograms (150 lb) of buoyancy a day from leakage, Andrée refused to acknowledge the alarming implications of this. Most modern students of the expedition see Andrée's unlimited optimism, faith in the power of technology, and disregard for the forces of nature as the main factors in the series of events that led to his death and the deaths of his two companions Nils Strindberg (1872–1897) and Knut Frænkel (1870–1897).

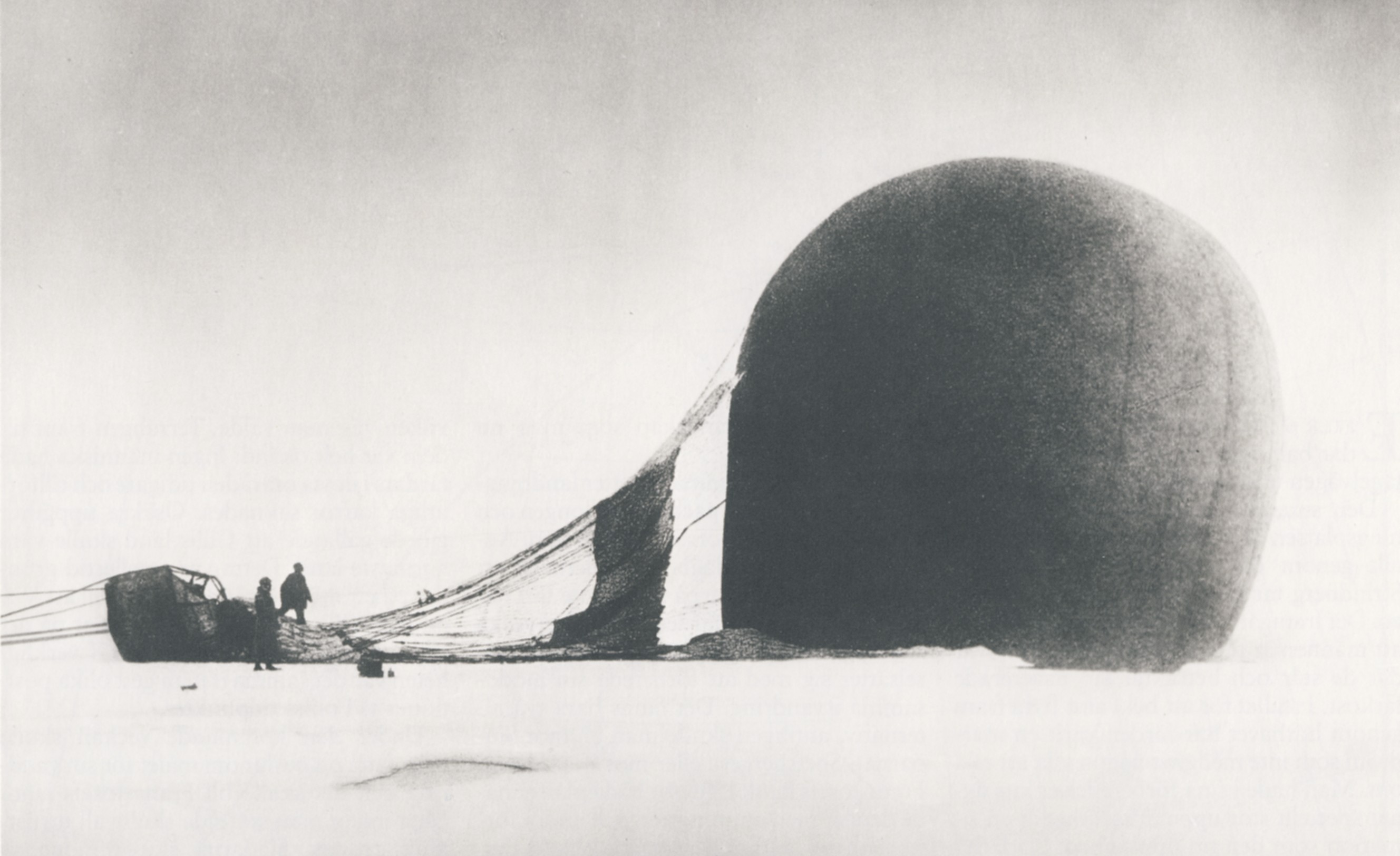

After Andrée, Strindberg, and Frænkel lifted off from Svalbard in July 1897, the balloon lost hydrogen quickly and crashed on the pack ice after only two days. The explorers were unhurt but faced a gruelling trek back south across the drifting icescape. Inadequately clothed, equipped, and prepared, and shocked by the difficulty of the terrain, they did not make it to safety. As the Arctic winter closed in in October, the group ended up exhausted on the deserted Kvitøya (White's Island) in Svalbard and died there. For 33 years, the fate of the Andrée expedition remained one of the unsolved riddles of the Arctic. The accidental discovery of the expedition's last camp on Kvitøya in 1930 created a media sensation in Sweden, where the dead men were mourned and idolized. Andrée's motives have later been re-evaluated, along with the role of the polar areas as the proving-ground of masculinity and patriotism. An early example is Per Olof Sundman's fictionalized bestseller novel of 1967, The Flight of the Eagle, which portrays Andrée as weak and cynical, at the mercy of his sponsors and the media. The verdict on Andrée by modern writers for virtually sacrificing the lives of his two younger companions varies in harshness depending on whether he is seen as the manipulator or the victim of Swedish nationalist hype around the turn of the 20th century.

S. A. Andrée's scheme

The second half of the 19th century has often been called the heroic age of polar exploration. The inhospitable and dangerous Arctic and Antarctic regions spoke powerfully to the Victorian imagination, not as lands with their own ecology and (in the case of the Arctic) cultures, but as challenges to technological ingenuity and manly daring.

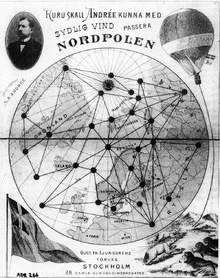

The Swede S. A. Andrée shared these enthusiasms, and proposed a plan for letting the wind propel a hydrogen balloon from Svalbard across the Arctic Sea to the Bering Straight, to fetch up in either Alaska, Canada, or Russia, and passing near or even right over the North Pole on the way. Andrée was an engineer at the patent bureau in Stockholm, with a passion for ballooning. In 1893 he bought his own balloon, the Svea, and made altogether nine journeys with her, starting from Göteborg or Stockholm and travelling a combined distance of 1,500 kilometres (930 mi). In the prevailing westerly winds, the Svea flights had a strong tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to the Baltic Sea and drag his basket perilously along the surface of the water and/or slam it into one of the many rocky islets in the Stockholm archipelago (see artist's impression, right, of Andrée being blown off an island, from the evening paper Aftonbladet). On one occasion he was blown clear across the Baltic to Finland. His longest trip was from Göteborg due east, across the breadth of Sweden and out over the Baltic to Gotland. Even though he actually saw a lighthouse and heard breakers off Öland, he remained convinced that he was travelling over land and merely seeing lakes.

The main purpose of Andrée's Svea flights was to test and perfect the drag rope steering technique which he had invented and wanted to use on his projected North Pole expedition. Drag ropes, which hang from the balloon basket and drag part of their length on the ground, are designed to counteract the tendency of lighter-than-air craft to travel at the same speed as the wind, a situation that makes steering by sails impossible. The friction of the ropes was intended to slow the balloon to the point where the sails would have an effect (beyond that of making the balloon rotate on its axis). Andrée claimed that, with the drag rope/sails steering, his Svea had essentially become a dirigible, but this notion is rejected by modern balloonists. The Swedish Ballooning Association ascribes Andrée's conviction entirely to wishful thinking, capricious winds, and the fact that much of the time Andrée was inside clouds and had little idea where he was or which way he was moving. Persistently, too, his drag ropes would snap, fall off, become entangled in one another, or get stuck to the ground, which could result in pulling the often low-flying balloon down into a dangerous bounce. No modern Andrée researcher has expressed any faith in drag ropes as a balloon steering technique.

Promotion and fundraising

The Arctic ambitions of the northern European nation of Sweden were still unrealized in the late 19th century, while neighboring and politically subordinate Norway was a world power in Arctic exploration through such pioneeers as Fridtjof Nansen. The Swedish political and scientific elite were eager to see Sweden take that lead among the Scandinavian countries which seemed her due, and Andrée, a persuasive speaker and fundraiser, found it easy to gain support for his ideas. At a lecture in 1895 to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Andrée thrilled the audience of geographers and meteorologists. A polar exploration balloon, he explained, would need to fulfill four conditions:

- It must have enough lifting power to carry three people and all their scientific equipment, advanced cameras for aerial photography, provisions for four months, and ballast, altogether about 3,000 kilograms (approximately 2.5 short tons).

- It must retain the gas well enough to stay aloft for 30 days.

- The hydrogen gas must be manufactured, and the balloon filled, at the Arctic launch site.

- It must be at least somewhat steerable.

Andrée gave a glowingly optimistic account of the ease with which these requirements could be met. Larger balloons had been constructed in France, he claimed, and more airtight, too. Some French balloons had remained hydrogen-filled for over a year without appreciable loss of buoyancy. As for the hydrogen, filling the balloon at the launch site could easily be done with the help of mobile hydrogen manufacturing units; for the steering, he referred to his own drag-rope experiments with the Svea, stating that a deviation of 27° from the wind direction could be routinely achieved.

Andrée assured the audience that Arctic summer weather was exceptionally suitable for ballooning. The midnight sun would enable observations round the clock, halving the voyage time required, and do away with all need for anchoring at night, which might otherwise be a dangerous business; nor, with constant daylight, would the balloon's buoyancy be adversely affected by the cold of night. The drag-rope steering technique was particularly well adapted for a region where the ground, consisting of ice, was "low in friction and free of vegetation". The minimal precipitation in the area posed no threat of weighing down the balloon; if, against expectation, some rain or snow did fall on the balloon, Andrée argued, "precipitation at above-zero temperatures will melt, and precipitation at below-zero temperatures will blow off, for the balloon will be travelling more slowly than the wind." The audience was convinced by these arguments, so disconnected from the realities of the Arctic summer storms, fogs, high humidity, and ever-present threat of ice formation. They also approved Andrée's expense calculation of 130,800 kronor in all, corresponding in today's money to just under a million dollars, of which the single largest sum, 36,000 kronor, was for the balloon itself. With this endorsement, there was a rush to support his project, headed by King Oscar II, who personally contributed 30,000 kronor, and Alfred Nobel, the dynamite magnate and founder of the Nobel Prize.

Sweden was gripped by uncritical polar balloon enthusiasm, and there was also considerable international interest, along with a more critical attitude. Andrée being Sweden's first balloonist, even very eminent Swedish geographers and meteorologists seemed ready to be credulous when he told them about his specialty, ballooning: nobody in the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences audience had the requisite knowledge to second-guess him about buoyancy or drag ropes. The situation was different in Germany and France, where there were long ballooning traditions and far more experienced balloonists than Andrée, several of whom expressed scepticism. The international reading public were curious about a project that seemed as modern and scientific as the books of contemporary writer Jules Verne, and European and American newspapers fanned the interest, along a spectrum from predictions of certain death for the explorers to mentions of the balloon as a "ship" or "airship" that would be safely "guided" to the North Pole in a scientific manner. "In these days, the construction and guidance of airships have been improved greatly", wrote the Providence Journal, "and it is supposed, both by the Parisian experts and by the Swedish scientists who have been assisting M. Andree, that the question of a sustained flight in this case will be very satisfactorily answered by the character of the balloon, by its careful guidance and, providing it gets into a Polar current of air, by the elements themselves." Eagerly followed by national and international media, Andrée began negotiations with the well-known aeronaut and balloon builder Henri Lachambre in Paris, world capital of ballooning, and ordered a varnished three-layer silk balloon, 20.5 metres (67 ft) in diameter, from his workshop. The balloon, originally called Le Pôle Nord, was to be renamed Örnen, meaning the Eagle.

The 1896 fiasco

For his 1896 attempt to launch the Eagle, Andrée had many eager volunteers from which to build his desired three-man team. He picked an experienced Arctic meteorological researcher, Nils Gustaf Ekholm (1848–1923), formerly his boss during an 1882–83 geophysical expedition to Spitsbergen, and Nils Strindberg (1872–1897), reputedly a brilliant student, who was doing original research in physics and chemistry. The main scientific purpose of the expedition was to map the area by means of aerial photography, and Strindberg was both a devoted amateur photographer and a skilled constructor of advanced cameras.

This was a team with many useful scientific and technical skills, but lacking any particular physical prowess or training for survival under extreme conditions. All three were indoor types, and only one of them, Strindberg, was young. Andrée expected a sedentary voyage in a balloon basket, and strength and survival skills were far down on his list.

Modern writers all agree that Andrée's North Pole scheme was unrealistic. He relied on the winds blowing more or less in the direction he wanted to go, on being able to fine-tune his direction with the drag ropes, on the balloon being sealed tight enough to stay airborne for 30 days, and on no ice or snow sticking to the balloon to weigh it down. In the attempt of 1896, the real polar wind immediately refuted his optimism by blowing steadily from the north, straight at the balloon hangar at Danskøya, until the expedition had to pack up, let the hydrogen out of the balloon, and go home. It is now known that northerly winds are to be expected at Danskøya, but in the late 19th century, information on Arctic airflow and precipitation existed only as contested academic hypotheses. Even Ekholm, the meteorologist and Arctic climate researcher, had no objection to Andrée's theory of where the wind was likely to take him. The observational data simply did not exist.

On the other hand, Ekholm was critical of the balloon's ability to retain hydrogen, and for this he had a solid empirical basis. Ekholm's buoyancy measurements in the summer of 1896, during the process of producing the hydrogen and pumping it into the balloon, convinced him that the Eagle leaked too much to ever reach the Pole, let alone go on to Russia or Canada. The worst leakage came from the multitude of tiny stitching holes along the seams, and no amount of glued-on strips of silk or applications of the special secret-formula varnish seemed to seal these holes. There were about eight million of them. The Eagle was losing 68 kilograms (150 lb) of lifting power a day and, taking into account its heavy load, Ekholm estimated that it would be able to stay airborne for 17 days at most, not 30. When it was time to go home, he warned Andrée that he himself would not be on board for the next attempt, scheduled for summer 1897, unless a stronger, better-sealed balloon than the original Eagle was purchased.

Andrée resisted Ekholm's criticisms to the point of deception. On the boat back from Svalbard, Ekholm learned from the chief engineer of the hydrogen plant the explanation of some anomalies he had noticed in his measurements: Andrée had from time to time secretly ordered extra topping-up of the hydrogen in the balloon. Andrée's motives for such self-destructive behavior are not known. Several modern writers, following Sundman's Andrée portrait in the semi-documentary novel The Flight of the Eagle (1967), have speculated that Andrée had by this time become the prisoner of his own successful funding campaign. The sponsors and the media followed every delay and reported on every setback, and were clamoring for results. Andrée, Strindberg, and Ekholm had been seen off by cheering, jubilant crowds in Stockholm and Göteborg (see image from Aftonbladet, right) and now all the expectations were coming to nothing with the long wait for southerly winds at Danskøya. Especially pointed was the contrast between Nansen's simultaneous return, covered in polar glory from his daring yet well-planned expedition, and Andrée's failure to even launch his own much-hyped conveyance. Andrée, theorizes Sundman, could not at this point face letting the press relay the message that he had, besides not knowing which way the wind would blow, also miscalculated in ordering the balloon, and would like another one.

After the 1896 launch was called off, enthusiasm for joining the expedition for a second attempt in 1897 did not run quite so high. There were still candidates, however, and Andrée picked out the 27-year-old engineer Knut Frænkel to replace Ekholm. Knut Frænkel was a civil engineer from the north of Sweden, an athlete and fond of long mountain hikes. He was enrolled specifically to take over Ekholm's meteorological observations, and, without any of Ekholm's theoretical and scientific knowledge, nevertheless handled this task efficiently. His meteorological journal has allowed the movements of the three men during their last few months to be reconstructed with considerable exactness.

The 1897 disaster

Launch, flight, and landing

Returning to Danskøya in the summer of 1897, the expedition found that the balloon hangar built the year before had weathered the winter storms well. The winds were more favorable, too, and Andrée's leadership more absolute, now that the critical Ekholm, an authority in his field and older than Andrée, had been replaced by the 27-year-old enthusiast Knut Frænkel. On July 11, in a steady wind from the southwest, the top of the plank hangar was dismantled, the three explorers climbed into the already heavy basket, and Andrée dictated one last-minute telegram to King Oscar and another to the paper Aftonbladet, holder of media rights to the expedition. The large support team cut away the last ropes holding the balloon and it rose slowly. Moving out over the water at low height, it was pulled so far down by the friction of the several hundred meter long drag ropes against the ground as to dip the basket into the water. The friction also twisted the ropes round, detaching them from their screw holds. These holds were a new safety feature which Andrée had reluctantly been persuaded to add, whereby ropes that got caught on the ground could be more easily dropped. Now most of them unscrewed at once and 530 kilograms (1170 lb) of rope were lost, while the three explorers could simultaneously be seen to dump 210 kilograms of sand overboard to get the basket clear of the water. 740 kilograms (1630 lb) of essential weight was thus lost in the first few minutes, and the Eagle, before it was well clear of the launch site, had turned from a supposedly steerable craft into an ordinary hydrogen balloon with a few ropes hanging from it, at the mercy of the wind, with no ability to aim at any particular goal and too little ballast. Lightened, it rose to 700 metres (2300 ft), a quite unforeseen height in any of the calculations made, where the lower air pressure made the hydrogen escape all the faster through the eight million little holes.

The balloon had two means of communication with the outside world, buoys and carrier pigeons. The buoys, steel cylinders encased in cork, were meant to be dropped from the balloon into the water or onto the ice, to be carried to civilisation by the currents. Only two buoy messages have ever been found. One of them was dispatched by Andrée on July 11, a few hours after takeoff, and reads "Our journey goes well so far. We sail at an altitude of about 250 m, at first N 10° east, but later N 45° east. Weather delightful. Spirits high." The second had been dropped an hour later and gave the height as 600 metres. The pigeons, optimistically bred in northern Norway, had been supplied by Aftonbladet, and their message cylinders contained pre-printed instructions in Norwegian asking the finder to pass the messages on to the newspaper's address in Stockholm. Andrée released at least four pigeons, but only one was ever retrieved, by a Norwegian steamer where the pigeon had alighted and been promptly shot. Its message is dated July 13 and gives the travel direction at that point as East by 10° South, adding "All well on board". Lundström and others note that these messages fail to mention the accident at takeoff, or the increasingly desperate situation, which was being detailed in Andrée's main diary: the balloon was out of equilibrium, sailing much too high and thereby losing hydrogen at a faster rate than even Nils Ekholm had feared, then repeatedly threatening to crash on the ice. All the sand and some of the payload was being thrown overboard to keep it airborne.

Free flight lasted for 10 hours and 29 minutes and was followed by another 41 hours of bumpy ride with frequent ground contact before the inevitable final crash. The Eagle thus travelled for 2 days and 3 1/2 hours altogether, during which time according to Andrée nobody on board got any sleep. The definitive landing appears to have been gentle. Everybody was unhurt, including the carrier pigeons in their wicker cages, and all the equipment was undamaged, even the delicate optical instruments and Strindberg's two cameras.

On foot on the ice

From the moment they were grounded, Strindberg's highly specialized cartographic camera, which had been brought to map the region from the air, became instead a means of recording daily life in the icescape and the constant danger and exhausting drudgery with which the three men clambered through it. Strindberg's pictures of the other two contemplating the fallen Eagle are famous; and throughout the journey, he kept setting up the seven kilogram (15 lb) camera on its tripod and photographing the channel crossings, the camps, the men (sometimes all three, showing the camera had a self-trigger mechanism), the equipment. Andrée and Frænkel also recorded events and, meticulously, positions, Andrée in his "main diary", Frænkel in his meteorological journal. Strindberg's own "speed-written" or stenographic, diary was more personal, taking the form of messages to his fiancee Anna, a journal in letters.

The Eagle had been stocked with safety equipment such as guns, snowshoes, sleds, skis, a tent, a small boat (in the form of a bundle of bent sticks, to be assembled and covered with balloon silk), most of it stored not in the basket but in the storage space arranged above the balloon ring. It had not been put together with great care, nor with any thought of the indigenous peoples' techniques for adapting to the extreme environment. In this Andrée contrasted not only with later but also with many earlier explorers. Sven Lundström points to the agonizing extra efforts that became necessary simply because the sleds Andrée had designed, of a rigid construction which owed nothing to Inuit sleds, were so impractical for the difficult terrain—"dreadful terrain", Andrée calls it—with its channels separating the ice floes, high ridges, and partially iced-over melt ponds. Their clothes did not include furs but consisted of woollen coats and trousers plus oilskins. A pervasive impression from Andrée's diary is that the explorers are never dry, and that the drying of clothes, mainly accomplished by wearing them, is a focus of attention. Danger was everywhere, as it would have meant certain death to lose the provisions lashed to one of the inconvenient sleds into one of the many channels that had to be laboriously crossed.

Before starting the march over the dreadful terrain, the three men spent a week in a tent at the crash site, packing up and making decisions about what and how much to bring and where to go. The far-off North Pole was not mentioned as an option; the choice lay between two depots of food and ammunition laid down for their safety, one at Cape Flora in Franz Josef Land and one at Seven Islands in Svalbard (see map). Thinking the distances to each about equal, from the faulty maps of the day, they decided to try for the bigger depot at Cape Flora. Strindberg took more pictures during this week than he would at any later point, including 12 frames that make up a 360° panorama of the crash site.

The balloon had carried a lot of food, of a kind more adapted for a balloon voyage than for travels on foot. Andrée had reasoned that they might as well throw excess food overboard as sand, if necessary; and if it was not necessary, the food would serve if wintering in the Arctic desert did after all become an issue. There was therefore less ballast and large amounts of heavy-type provisions, 767 kilograms (1690 lb) altogether, including 200 liters of water and some crates of champagne, port, beer, etc., donated by sponsors and/or manufacturers. There was also lemon juice, though not as much of this precaution against scurvy as other polar explorers usually thought necessary. Much of the food was in the form of cans of pemmican, meat, cheese, and condensed milk. Some of it had in fact been thrown over board. The three men took most of the rest with them on leaving the crash site, along with other necessities such as guns, tent, ammunition, and cooking utensils, making a load on each sled of more than 200 kilograms (440 lb). This was not realistic, as it broke the sleds and wore out the men, and after one week a big pile of food and non-essential equipment was left behind, bringing the loads down to 130 kilograms per sled. It became then more than ever necessary to hunt for food. Seals, walruses, and especially polar bears were shot and eaten throughout the march.

Starting out for Franz Josef Land to the southeast on July 22, they soon found that their struggle across the ice with its two-storey-high ridges was hardly bringing the goal any nearer: the drift of the ice was in the opposite direction, moving them backwards. On August 4 they decided, after a long discussion, to aim for Seven Islands in the southwest instead, hoping to reach the depot there after a six to seven week march, with the help of the current. The terrain in that direction was mostly extremely difficult, sometimes necessitating a crawl on all fours, but there was occasional relief in the form of open water — the little boat (not designed by Andrée) was apparently a functional and safe conveyance — and smooth, flat ice floes. "Paradise!" wrote Andrée. "Large even ice floes with pools of sweet drinking water and here and there a tender young polar bear!" They made fair apparent headway, but the wind turned almost as soon as they did and they were again being moved backwards, away from Seven Islands. The wind varied between southwest and northwest over the coming weeks, which they tried in vain to overcome by turning their own course more and more westward, but it was becoming clear that Seven Islands was out of their reach.

On September 12 the explorers resigned themselves to wintering on the ice and camped on a large floe, letting the ice take them where it would, "which", writes Kjellström, "it had really been doing all along" (p. 47). Drifting rapidly due south towards Kvitøya, they hurriedly built a winter "home" on the floe against the growing cold, with walls made of water-reinforced snow to Strindberg's design, see plan left. Observing the rapidity of their drift, Andrée recorded his hopes that they might get far enough south to feed themselves entirely from the sea. However, on October 2 the floe began to break up directly under the hut from the stresses of pressing against Kvitøya, and they were forced to bring their stores on to the island itself, which took a couple of days. "Morale remains good", reports Andrée at the very end of the coherent part of his diary, which ends with the sentence: "With such comrades as these, one ought to be able to manage under practically any circumstances whatsoever". It is believed, on the basis of the incoherent and badly damaged last pages of Andrée's diary, that the three men were all dead within a few days of moving on to the island.

Cause of death

The bodies of the Eagle crew were cremated without further examination upon being returned to Sweden. The question of what, exactly, killed them has attracted both interest and controversy among scholars, and several medical practitioners and amateur historians have also read the extensive diaries with a detective's eye, looking for clues in the diet, for telltale complaints of symptoms, and for suggestive details at the death site. The main factors extracted are these: they mostly ate scanty amounts of canned and dry goods from the Eagle stores plus huge portions of half-cooked meat of polar bears and occasionally seals; they suffered often from foot pains and diarrhea, and were always tired, cold, and wet; and they had left much of their valuable equipment and stores outside the tent on Kvitøya, and even down by the water's edge, as if they were too exhausted, indifferent, or ill to take it further. Strindberg, the youngest member of the expedition, had died first and been buried (in the sense of wedged into a cliff aperture) by the others.

The best-known and most widely credited suggestion was made by Ernst Tryde, a medical doctor, in his book De döda på Vitön in 1952: that the men succumbed to trichinosis that they got from eating undercooked polar bear meat. Larvae of Trichinella spiralis were found in parts of a polar bear carcass at the site. Other suggestions include lead poisoning from the cans their food was stored in, vitamin A poisoning from eating polar bear liver, scurvy, botulism, carbon monoxide poisoning, suicide (they had plenty of opium), polar bear attack, cold and exposure as the Arctic winter closed in, and dehydration in combination with general exhaustion, apathy, and disappointment.

Myth and legacy

For the next 33 years the lost expedition was part of cultural lore in Sweden and to a lesser extent elsewhere. It was actively sought for a couple of years and remained the subject of myth and rumor, with newspaper reports of possible findings surfacing persistently. An extensive archive of American newspaper reports from the first few years, 1896–1899, entitled "The Mystery of Andree", shows a much richer media interest in the expedition after it disappeared than before, and a great variety of suggested fates for it, inspired by finds, or reported finds, of remnants of a wicker balloon basket or great amounts of balloon silk, or by stories of men falling from the sky, or visions by psychics, all of which would typically locate the stranded balloon far from Danskøya and Svalbard. Lundström points out (p. 134) that some of the international and national reports take on the features of urban legends and reflect a prevailing disrespect for the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, who frequently appear in the newspapers as uncomprehending savages and kill the three men or show a deadly indifference to their plight. When their remains and records were accidentally found in 1930, after the fate of the expedition had been shrouded in mystery for 33 years, the harrowing story told by the diaries and photos had no similarity to any of the speculations.

In 1897, Andrée's daring, or foolhardy, undertaking nourished Swedish patriotic pride and Swedish dreams of taking the scientific lead in the Arctic. The title of "Engineer" — "Ingenjör Andrée" — was generally and reverentially used in speaking of him, and expressed high esteem for the late 19th-century ideal figure of the engineer as a representative of social improvement through technological progress. The three explorers were fêted when they departed and mourned by the nation when they disappeared. When they were found, they were celebrated for the heroism of their doomed two-month struggle to reach populated areas and were seen as having selflessly perished for the ideals of science and progress. The home-bringing of their mortal remains to Stockholm on October 5, 1930, writes Swedish historian of ideas Sverker Sörlin, "must be one of the most solemn and grandiose manifestations of national mourning that has ever occurred in Sweden. One of the rare comparable events is the national mourning that followed the Estonia disaster in the Baltic Sea in September 1994" (p. 100).

More recently, Andrée's heroic motives have been questioned, beginning with Per Olof Sundman's bestselling semi-documentary novel of 1967, The Flight of the Eagle. Sundman's interpretation of the personalities involved, the blindspots of the Swedish national culture, and the role of the press carries over into the Oscar-nominated film by Jan Troell, Flight of the Eagle (1982), which is based on Sundman's novel.

Appreciation of the role of Nils Strindberg seems to be growing, both for the fortitude with which the untrained and unprepared student kept photographing at all in what must have been a more or less permanent state of near-collapse from exhaustion and exposure, and for the artistic quality of the result. Out of the 240 exposed frames that were found on Kvitøya in waterlogged containers, 93 were saved by John Hertzberg at Strindberg's own workplace the Royal Institute of Technology of Stockholm. In his article "Recovering the visual history of the Andrée expedition" (2004), Tyrone Martinsson has lamented the traditional focus by previous researchers on the written records — the diaries — as primary sources of information, and made a renewed claim for the historical significance of the photos.

Notes

- Andrée, christened Salomon August, invariably went by his initials as an adult.

- This assessment is discussed in several contexts in Vår position är ej synnerligen god... by Andrée specialist Sven Lundström, curator of the Andrée museum in Grenna, Sweden (see for example p. 131).

- See Kjellström, p. 45, Lundström, p. 131, Martinsson.

- For instance in the title of John Maxtone-Graham's popularized narrative Safe Return Doubtful: The Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, which has a chapter on the Andrée expedition.

- The most complete account of the Svea voyages is at "Andrées färder".

- "Andrées färder".

- The information in this section is based on Sven Lundström's Vår position är ej synnerligen god..., pp. 19–44.

- See this price level chart from Statistiska centralbyrån, Sweden.

- Lundström, pp. 21–27.

- See for instance the Albany Express, Albany, NY. Jan. 16, 1896.

- Providence, RI, January 21, 1896. Both the examples given here come from "The Mystery of Andree", an extensive archive of American newspaper reports from 1896–1899.

- Lundström, p. 36.

- The account of Andrée's and Ekholms computations and hypotheses in this section relies on Kjellström, passim.

- Lundström, p. 59.

- See Kjellström, p. 45, and Lundström, pp. 69–73.

- The information in the 1897 section comes from Lundström, pp. 73–114, unless otherwise indicated.

- Lundström, p. 81.

- Kjellström, p. 45.

- The account in this section is based on the expedition's diaries and photos in Med Örnen mot polen plus some of Sven Lundström's commentary in "Vår position är ej synnerligen god...".

- Lundström, pp. 93–96.

- That the series of frames is designed as a panorama was only noticed in the 2004 study by Tyrone Martinsson, who has created an animated web version of it, see Martinsson. The panorama can be seen here.

- Andrée's diary, August 6, Med Örnen mot polen, p. 409.

- Mark Personne, a poison specialist who made the suggestion of botulism in "Andrée-expeditionens män dog troligen av botulism" in 2000, also provides a (for Swedish speakers) convenient overview of other theories to date.

- See "The Mystery of Andree".

- Lundström, pp. 89–91.

- See Martinsson.

References

- Andrée, S. A., Nils Strindberg, and Knut Frænkel (1930). Med Örnen mot polen: Andrées polarexpedition år 1897. Stockholm: Bonnier, 1930. The London edition of the English translation, by Edward Adams-Ray, is The Andrée diaries being the diaries and records of S. A. Andrée, Nils Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel written during their balloon expedition to the North Pole in 1897 and discovered on White Island in 1930, together with a complete record of the expedition and discovery; with 103 illustr. and 6 maps, plans and diagrams (1931); while the New York edition of the same translation is Andrée's Story: The Complete Record of His Polar Flight, 1897, Blue Ribbon Books, 1932.

- "Andrées färder", Svenska ballongfederationen. In Swedish. Accessed on March 5, 2006.

- Grenna Museum Andrée biography. In Swedish. Accessed on March 5, 2006.

- Kjellström, Rolf (1999). "Andrée-expeditionen och dess undergång: tolkning nu och då", in The Centennial of S.A. Andrée's North Pole Expedition: Proceedings of a Conference on S.A. Andrée and the Agenda for Social Science research of the Polar Regions, ed. Urban Wråkberg. Stockholm: Center for History of Science, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In Swedish.

- Lundström, Sven (1997). "Vår position är ej synnerligen god..." Andréexpeditionen i svart och vitt. Borås: Carlssons förlag. Lundström is the curator of the Andrée museum in Grenna, Sweden. In Swedish.

- Martinsson, Tyrone (2004). "Recovering the visual history of the Andrée expedition: A case study in photographic research". In Research Issues in Art Design and Media, ISSN 1474-2365, issue 6. Accessed 27 Feb 2006. This paper is based on Martinsson's doctoral dissertation from 2003. In English.

- "The Mystery of Andree", an extensive archive of American daily newspaper articles 1896–1899, from reports of the preparation and the launch to guesswork and rumours about the explorers' fate. Accessed on March 5, 2006.

- Personne, Mark (2000). "Andrée-expeditionens män dog troligen av botulism". Läkartidningen, vol. 97, issue 12,1427–1432. In Swedish. Accessed on March 13, 2006.

- Sörlin, Sverker (1999). "The burial of an era: the home-coming of Andrée as a national event", in The Centennial of S.A. Andrée's North Pole Expedition: Proceedings of a Conference on S.A. Andrée and the Agenda for Social Science research of the Polar Regions, ed. Urban Wråkberg. Stockholm: Center for History of Science, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In English.

- Sundman, Per Olov (1967). Ingenjör Andrées luftfärd. Stockholm: Norstedt. Translated in 1970 by Mary Sandbach as The Flight of the Eagle, London: Secker and Warburg. The 1982 film Flight of the Eagle by Jan Troell is based on this novel.

- Tryde, Ernst Adam (1952). De döda på Vitön: sanningen om Andrée. Stockholm: Bonnier.

External links

- Template:Pl iconAndrzej M. Kobos "Orłem" do bieguna, high-quality photos from the expedition. Accessed on March 5, 2006.