| Revision as of 23:08, 20 November 2011 editFaustian (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers10,317 edits →Atrocities against Jews: added referenced notable fact (how the army is/was perceived by Jews)← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:16, 20 November 2011 edit undoFaustian (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers10,317 edits →Atrocities against Jews: added facts from this bookNext edit → | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

| Although Haller's Army has been highly regarded by Poles, Jews remember it as a group engaged in antisemitic acts. <ref> Antony Polonsky. (1990). ''My brother's keeper?: recent Polish debates on the Holocaust.'' Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies: Oxford, England. pg. 100. </ref> | Although Haller's Army has been highly regarded by Poles, Jews remember it as a group engaged in antisemitic acts. <ref> Antony Polonsky. (1990). ''My brother's keeper?: recent Polish debates on the Holocaust.'' Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies: Oxford, England. pg. 100. </ref> | ||

| After their arrrival to Eastern Europe Haller's troops engaged in looting, violence and atrocities against Jews. Haller's troops established a reputation as, in the words of scholar Pavel Korzec, "the worst torturers of Jews."<ref> Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035 </ref><ref>Heiko Haumann. (2002). ''A history of East European Jews '' Central European University Press, pg. 215 </ref><ref> Justyna Wozniakowska. (2002). Master's Thesis, Central European University Nationalism Studios Program pg. 22 </ref> | After their arrrival to Eastern Europe Haller's troops engaged in looting, violence and atrocities against Jews. Haller's troops established a reputation as, in the words of scholar Pavel Korzec, "the worst torturers of Jews." <ref> Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035 </ref><ref>Heiko Haumann. (2002). ''A history of East European Jews '' Central European University Press, pg. 215 </ref><ref> Justyna Wozniakowska. (2002). Master's Thesis, Central European University Nationalism Studios Program pg. 22 </ref> As they travelled East, Haller's soldiers plundered Jewish houses, pushed Jews off moving trains, and cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews, particularly the elderly, with their bayonets as crowds watched. <ref> Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035 </ref> | ||

| Haller's Army has been accused of committing the ] in 1918. ] states that after helping to capture ], the Blue Army forces, together with other Polish civilians, enagaged in ] against the Jewish and Ukrainian inhabitants resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths .<ref>William W. Hagen. Murder in the East: German-Jewish Liberal Reactions to Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland and Other East European Lands, 1918–1920. ''Central European History'', Volume 34, Number 1, 2001 , pp. 1-30. Page 8.</ref> However, according to the Cambridge History of Poland, in 1918 the Army was still in France where it took part in final stages of military operations on the Western Front, and the first units of the Blue Army did not reach Poland until the spring of 1919.<ref>William Fiddian Reddaway, '''', pg. 477, Cambridge University Press, 1971.</ref> Likewise ''Kronika Polski'' gives April 14, 1919, more than four months after the pogrom took place, as the date that the first transports of Blue Army soldiers departed France for Poland.<ref>Andrzej Nowak, ''Kronika Polski'', Kluszczynski Publishers, 1998</ref> Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen states that the first units of the Blue Army did not leave France until April 15th, 1919, its departure having been delayed by opposition from Britain and United States.<ref>Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen, '''', pg. 225, Odense University Press, 1979</ref> Another source states that a special protocol had to be agreed to before the Blue Army could return to Poland, and that this did not happen until April of 1919, and thus the Blue Army was not in Poland during the first six months of Polish independence.<ref>Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman, Elisabeth Gläser, '''', pg. 324, Cambridge University Press, 1998</ref> Wandycz gives April 4th, 1919, as the data on which this special protocol, named after Marshall Foch and the German diplomat ], was finally signed.<ref>Piotr Stefan Wandycz, ''''</ref> This suggests that William Hagen erred when he ascribed responsibility for the Lwow pogrom to Haller's army. | Haller's Army has also been accused of committing the ] in 1918. ] states that after helping to capture ], the Blue Army forces, together with other Polish civilians, enagaged in ] against the Jewish and Ukrainian inhabitants resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths .<ref>William W. Hagen. Murder in the East: German-Jewish Liberal Reactions to Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland and Other East European Lands, 1918–1920. ''Central European History'', Volume 34, Number 1, 2001 , pp. 1-30. Page 8.</ref> However, according to the Cambridge History of Poland, in 1918 the Army was still in France where it took part in final stages of military operations on the Western Front, and the first units of the Blue Army did not reach Poland until the spring of 1919.<ref>William Fiddian Reddaway, '''', pg. 477, Cambridge University Press, 1971.</ref> Likewise ''Kronika Polski'' gives April 14, 1919, more than four months after the pogrom took place, as the date that the first transports of Blue Army soldiers departed France for Poland.<ref>Andrzej Nowak, ''Kronika Polski'', Kluszczynski Publishers, 1998</ref> Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen states that the first units of the Blue Army did not leave France until April 15th, 1919, its departure having been delayed by opposition from Britain and United States.<ref>Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen, '''', pg. 225, Odense University Press, 1979</ref> Another source states that a special protocol had to be agreed to before the Blue Army could return to Poland, and that this did not happen until April of 1919, and thus the Blue Army was not in Poland during the first six months of Polish independence.<ref>Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman, Elisabeth Gläser, '''', pg. 324, Cambridge University Press, 1998</ref> Wandycz gives April 4th, 1919, as the data on which this special protocol, named after Marshall Foch and the German diplomat ], was finally signed.<ref>Piotr Stefan Wandycz, ''''</ref> This suggests that William Hagen erred when he ascribed responsibility for the Lwow pogrom to Haller's army. | ||

| Despite the examples of ] and antisemitic atrocites committed by Haller's army ,<ref> Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035 </ref><ref>Heiko Haumann. (2002). ''A history of East European Jews '' Central European University Press, pg. 215 </ref><ref name = "Goldstein"> Goldstein, Edward. The Galitzianer, the quarterly journal of Gesher Galicia, May 2002. Goldstein states: "Based on the evidence I have considered I conclude that: (1) individual Hallerczyki and probably units of Haller’s Army committed anti-Semitic atrocities while in Poland, and (2) thousands of Jews served in Haller’s Army.</ref> Jews fought within its ranks, some even rising to rank of officer. Much of the original source material has been lost, stolen or destroyed, first by Nazi occupation during World War II and later by 50 years of Communist suppression. Only recently has some documentation come to the surface. | Despite the examples of ] and antisemitic atrocites committed by Haller's army ,<ref> Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035 </ref><ref>Heiko Haumann. (2002). ''A history of East European Jews '' Central European University Press, pg. 215 </ref><ref name = "Goldstein"> Goldstein, Edward. The Galitzianer, the quarterly journal of Gesher Galicia, May 2002. Goldstein states: "Based on the evidence I have considered I conclude that: (1) individual Hallerczyki and probably units of Haller’s Army committed anti-Semitic atrocities while in Poland, and (2) thousands of Jews served in Haller’s Army.</ref> Jews fought within its ranks, some even rising to rank of officer. Much of the original source material has been lost, stolen or destroyed, first by Nazi occupation during World War II and later by 50 years of Communist suppression. Only recently has some documentation come to the surface. | ||

Revision as of 23:16, 20 November 2011

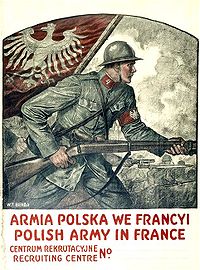

For other uses, see Blue Army (disambiguation).The Blue Army, or Haller's Army, are informal names given to the Polish Army units formed in France during the later stages of World War I. The army was created in June 1917 as part of the Polish units allied to the Entente. After the Great War ended, the units were transferred to Poland, where they took part in the Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Bolshevik War. The nicknames come from the soldier's French blue uniforms and the name of the army's commander, General Józef Haller de Hallenburg.

History

Formation and Service on the Western Front

The first units were formed after the signing of a 1917 alliance by French President Raymond Poincaré and the Polish statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski. A majority of recruits were either Poles serving in the French army, or former prisoners of war from the German and Austro-Hungarian imperial armies (approximately 35,000 men). An additional 23,000 were Polish Americans. Other Poles flocked to the army from all over the world as well — these units included recruits from the former Russian Expeditionary Force in France and the Polish diaspora in Brazil (more than 300 men).

The army was initially under French political control and under the military command of General Louis Archinard. However, on February 23, 1918, political sovereignty was granted to the Polish National Committee and soon other Polish units were formed, most notably the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions in Russia. On September 28 Russia formally signed an agreement with the Entente that accepted the Polish units in France as the only, independent, allied and co-belligerent Polish army. On October 4, 1918 the National Committee appointed General Józef Haller de Hallenburg as overall commander.

The first unit to enter combat on the Western Front was the 1st Rifle Regiment (1 pułk strzelców), fighting from July 1918 in Champagne and the Vosges mountains. By October the entire 1st Rifle Division joined the fight in the area of Rambervillers and Raon-l'Étape.

Transport to Poland

The army continued to gather new recruits after the end of The Great War on November 11, 1918, many of them ethnic Poles who had been conscripted into the Austrian army and later taken prisoners by the Allies. By early 1919 it numbered 68,500 men, fully equipped by the French government. After being denied permission by the German government to enter Poland via the Baltic port city of Danzig (Gdańsk), transport was arranged via train. Between April and June of that year the units were transported together intact to a reborn Poland across Germany in sealed train cars. Weapons were secured in separate cars and kept under guard to appease German concerns about a foreign army traversing its territory. Immediately after its arrival the divisions were integrated into the overall Polish Army and transported to the fronts of the Polish-Ukrainian War, then being fought over control of eastern Galicia.

The perilous journey from France, through revolutionary Germany, into Poland, in the spring of 1919 has been documented by those who lived through it:

Captain Stanislaw I. Nastal

Preparations for the departure lasted for some time. The question of transit became a difficult and complicated problem. Finally after a long wait a decision was made and officially agreed upon between the Allies and Germany.

The first transports with the Blue Army set out in the first half of April 1919. Train after train tore along though Germany to the homeland, to Poland.

Major Stefan Wyczolkowski

On 15 April 1919 the regiment began its trip to Poland from the Bayon railroad station in four transports, via Mainz, Erfurt, Leipzig, Kalisz, and Warsaw, and arrived in Poland, where it was quartered in individual battalions;, in Chelm 1st Battalion, supernumerary company and command of the regiment; 3rd Battalion in Kowel; and the 2nd Battalion in Wlodzimierz.

Major Stanislaw Bobrowski

On 13 April 1919 the regiment set out across Germany for Poland, to reinforce other units of the Polish army being created in the homeland amid battle, shielding with their youthful breasts the resurrected Poland.

Major Jerzy Dabrowski

Finally on 18 April 1919 the regiment’s first transport set out for Poland. On 23 April 1919 the leading divisions of the 3rd Regiment of Polish Riflemen set foot on Polish soil, now free thanks to their own efforts.

Lt. Wincenty Skarzynski

Weeks passed. April 1919 arrived – then plans were changed: it was decided irrevocably to transport our army to Gdansk instead by trains, through Germany. Many officers came from Poland, among them Major Gorecki, to coordinate technical details with General Haller.

Fighting in Galicia and Volhynia

Haller's Army changed the balance of power in Galicia and in Volhynia, and its arrival allowed the Poles to repel the Ukrainians and establish a demarcation line at the river Zbruch. on May 14, 1919. Haller's army was well equipped by the Western allies and partially staffed with experienced French officers specifically in order to fight against the Bolsheviks and not the forces of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic. Despite this obligation, the Poles dispatched Haller's army against the Ukrainians rather than the Bolsheviks in order to break the stalemate in eastern Galicia. The allies sent several telegrams ordering the Poles to halt their offensive as using of the French-equipped army against the Ukrainian specifically contradicted the conditions of the French help, but these were ignored with Poles claiming that "all Ukrainians were Bolsheviks or something close to it".

.

In July 1919 the Army was transferred to the border with Germany in Silesia, where it prepared defences against any possible German invasion.

Haller's well trained and highly motivated troops, as well as their airplanes and excellent FT-17 tanks, formed part of the core of the Polish forces during the ensuing Polish-Bolshevik War.

As with most of the history related to the Polish-Soviet War, information on the Blue Army was censored, distorted and repressed by the Soviet Union during its communist oppression of the 1945-1989 People's Republic of Poland.

The 15th Infantry Rifle Regiment of the Blue Army was the basis for the 49th Hutsul Rifle Regiment of the 11th Infantry Division (Poland)

Atrocities against Jews

Although Haller's Army has been highly regarded by Poles, Jews remember it as a group engaged in antisemitic acts. After their arrrival to Eastern Europe Haller's troops engaged in looting, violence and atrocities against Jews. Haller's troops established a reputation as, in the words of scholar Pavel Korzec, "the worst torturers of Jews." As they travelled East, Haller's soldiers plundered Jewish houses, pushed Jews off moving trains, and cut off the beards of Orthodox Jews, particularly the elderly, with their bayonets as crowds watched.

Haller's Army has also been accused of committing the pogrom of Jews in Lviv in 1918. William W. Hagen states that after helping to capture Lviv, the Blue Army forces, together with other Polish civilians, enagaged in three days of violence against the Jewish and Ukrainian inhabitants resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths . However, according to the Cambridge History of Poland, in 1918 the Army was still in France where it took part in final stages of military operations on the Western Front, and the first units of the Blue Army did not reach Poland until the spring of 1919. Likewise Kronika Polski gives April 14, 1919, more than four months after the pogrom took place, as the date that the first transports of Blue Army soldiers departed France for Poland. Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen states that the first units of the Blue Army did not leave France until April 15th, 1919, its departure having been delayed by opposition from Britain and United States. Another source states that a special protocol had to be agreed to before the Blue Army could return to Poland, and that this did not happen until April of 1919, and thus the Blue Army was not in Poland during the first six months of Polish independence. Wandycz gives April 4th, 1919, as the data on which this special protocol, named after Marshall Foch and the German diplomat Matthias Erzberger, was finally signed. This suggests that William Hagen erred when he ascribed responsibility for the Lwow pogrom to Haller's army.

Despite the examples of pogroms and antisemitic atrocites committed by Haller's army , Jews fought within its ranks, some even rising to rank of officer. Much of the original source material has been lost, stolen or destroyed, first by Nazi occupation during World War II and later by 50 years of Communist suppression. Only recently has some documentation come to the surface.

A number of Jews serving in Haller’s Army were officially listed as fatalities in the 43rd Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen (62 names identified by Edward Goldstein as "Jewish-sounding" out of 1,381, or approximately 5% of the soldiers). This military unit was initially incorporated into the 1st Regiment of the Foreign Legion, but due to protests from the Russian Government, it was split off and renamed the Legion of Bajonczyzy, then to the 1st Moroccan Division.

Order of battle

- I Polish Corps

- 1st Rifle Division

- 2nd Rifle Division

- 1st Heavy Artillery Regiment

- II Polish Corps - formed in Russia

- III Polish Corps

- 3rd Rifle Division

- 6th Rifle Division

- 3rd Heavy Artillery Regiment

- Independent Units

- 7th Rifle Division

- Training Division - cadre

- 1st Tank Regiment

See also

Bibliography

- Paul Valasek, Haller's Polish Army in France, Chicago, 2006

References

- The Blue Division, Stanislaw I. Nastal, Polish Army Veteran’s Association in America, Cleveland, Ohio 1922

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 43rd regiment of the Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stefan Wyczolkowski, Warsaw 1928

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 44th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Riflemen, Major Stanislaw Bobrowski, Warsaw 1929

- Outline of the Wartime History of the 45th Regiment of Eastern Frontier Infantry Riflemen, Major Jerzy Dabrowski, Warsaw 1928

- The Polish Army in France in Light of the Facts, Wincenty Skarzynski, Warsaw 1929

- Watt, R. (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its fate 1918-1939. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Subtelny, op. cit., p. 370

- Antony Polonsky. (1990). My brother's keeper?: recent Polish debates on the Holocaust. Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies: Oxford, England. pg. 100.

- Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Hostages of modernization: studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Volume 2 Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035

- Heiko Haumann. (2002). A history of East European Jews Central European University Press, pg. 215

- Justyna Wozniakowska. (2002). Master's Thesis, Central European University Nationalism Studios Program CONFRONTING HISTORY, RESHAPING MEMORY: THE DEBATE ABOUT JEDWABNE IN THE POLISH PRESS pg. 22

- Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Hostages of modernization: studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Volume 2 Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035

- William W. Hagen. Murder in the East: German-Jewish Liberal Reactions to Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland and Other East European Lands, 1918–1920. Central European History, Volume 34, Number 1, 2001 , pp. 1-30. Page 8.

- William Fiddian Reddaway, The Cambridge history of Poland, Volume 2, pg. 477, Cambridge University Press, 1971.

- Andrzej Nowak, Kronika Polski, Kluszczynski Publishers, 1998

- Kay Lundgreen-Nielsen, The Polish problem at the Paris Peace Conference: a study of the policies of the Great Powers and the Poles, 1918-1919, pg. 225, Odense University Press, 1979

- Manfred F. Boemeke, Gerald D. Feldman, Elisabeth Gläser, The Treaty of Versailles: a reassessment after 75 years, Volume 1919, pg. 324, Cambridge University Press, 1998

- Piotr Stefan Wandycz, http://books.google.com/books?id=NNMIo36qQXwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=France+and+her+eastern+allies,+1919-1925:+French-Czechoslovak-Polish&hl=en&ei=w9gpTZnsBImfnAff-bmfAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Haller&f=false

- Pavel Korzec. (1993). Polish-Jewish Relations During World War I. In Hostages of modernization: studies on modern antisemitism, 1870-1933/39, Volume 2 Herbert Strauss, Ed. Walter de Gruyter: pp.1034-1035

- Heiko Haumann. (2002). A history of East European Jews Central European University Press, pg. 215

- ^ Goldstein, Edward. Jews in Haller's Army. The Galitzianer, the quarterly journal of Gesher Galicia, May 2002. Goldstein states: "Based on the evidence I have considered I conclude that: (1) individual Hallerczyki and probably units of Haller’s Army committed anti-Semitic atrocities while in Poland, and (2) thousands of Jews served in Haller’s Army. Cite error: The named reference "Goldstein" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Wyczolkowski, Major Stefan, Outline of the Wartime History of the 43rd Regiment of the Eastern Frontier Riflemen Warsaw 1928, as commissioned by the Military Historical Office

External links

- Haller Army Website

- Józef Haller and the Blue Army

- THE POLISH ARMY IN FRANCE: IMMIGRANTS IN AMERICA, WORLD WAR I VOLUNTEERS IN FRANCE, DEFENDERS OF THE RECREATED STATE IN POLAND by DAVID T. RUSKOSKI