| Revision as of 18:43, 24 March 2013 editMy very best wishes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users56,376 edits →World War II← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:17, 5 April 2013 edit undoGalassi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,902 edits →World War II: mistranslation corrected and completed as well.Next edit → | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| ===World War II=== | ===World War II=== | ||

| Ehrenburg was active in war journalism throughout World War II. As a consequence, he is | Ehrenburg was active in war journalism throughout World War II. As a consequence, he is | ||

| one of many Soviet writers, along with ] and ], who have been accused by many of " their literary talents to the ] during ].<ref name="Figes">] ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'', 2007, ISBN 00805074619 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Invalid length.}}, page 414.</ref> His article ''"Kill"'' published in 1942 — when German troops were deeply within Soviet territory — became a widely publicized example of this campaign, along with the poem ''"Kill him!"'' by Simonov<ref>(Text is found in Ilya Ehrenburg's book Vojna (The war) (Moscow, 1942-43)</ref><ref></ref>. In "Kill", Ehrenburg wrote: "We shall kill. If you have not killed at least one German a day, |

one of many Soviet writers, along with ] and ], who have been accused by many of " their literary talents to the ] during ].<ref name="Figes">] ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'', 2007, ISBN 00805074619 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Invalid length.}}, page 414.</ref> His article ''"Kill"'' published in 1942 — when German troops were deeply within Soviet territory — became a widely publicized example of this campaign, along with the poem ''"Kill him!"'' by Simonov<ref>(Text is found in Ilya Ehrenburg's book Vojna (The war) (Moscow, 1942-43)</ref><ref></ref>. In "Kill", Ehrenburg wrote: "We know all. We remember all. We have understood: Germans are not human. From now on the word "German" is the worst kind of curse. From now on the word "German" causes a rifle to discharge. We shall not talk. We shall kill. If you have not killed at least one German a day, that day will be wasted. If you think that your neighbor would kill a German, you haven't understood the threat. If you do not kill the German, he will kill you. If you don't kill a German, he will he will take your family and torture them in his damned Germany. If you cannot kill your German with a bullet, kill him with your bayonet. If there is calm on your part of the front, if you are waiting for the fighting, kill a German before combat. If you leave a German alive, the German will hang a Russian man and rape a Russian woman. If you kill one German, kill another - there is nothing more amusing for us than a German corpses. Do not count days; do not count miles. Count only the number of Germans you have killed. Kill a German - Your old mother asks you for that. Kill a German - your child asks you for that. Kill a German - your native land asks you for that." After criticism by ] in ] in April 1945,<ref></ref>, Ehrenburg responded that he never meant wiping out the ], but only German aggressors who came to our soil with weapons, because "we are not Nazi" to fight with civilians<ref></ref>. He wrote already in May 1942 : "The German soldier with weapon in hand is not a man for us, but a fascist. We hate him When the German soldier gives up his weapon and surrenders, we will not touch him with a finger - he will live."<ref>"On Hatred", May 1942</ref>. Ehrenburg fell in disgrace at that time and it is estimated that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.<ref>Joshua Rubenstein: Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. 1st Paperback Ed., University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa (Alabama/USA) 1999 (= Judaic Studies Series), ISBN 0-8173-0963-2</ref><ref>Carola Tischler: Die Vereinfachungen des Genossen Ehrenburg. Eine Endkriegs- und eine Nachkriegskontroverse. In: Elke Scherstjanoi (Hrsg.): Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland. Briefe von der Front (1945) und historische Analysen. Texte und Materialien zur Zeitgeschichte, Bd. 14. K.G. Saur, München 2004, S. 326–339, ISBN 3-598-11656-X, p. 336-</ref> | ||

| Ehrenburg was a prominent member of the ]. | Ehrenburg was a prominent member of the ]. | ||

Revision as of 03:17, 5 April 2013

Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (Template:Lang-ru, pronounced [ɪˈlʲja ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪvɪtɕ erʲɪnˈburk] ; Kiev, January 27 [O.S. January 15] 1891 – Moscow, August 31, 1967) was a Soviet writer, journalist, translator, and cultural figure.

Ehrenburg is among the most prolific and notable authors of the Soviet Union; he published around one hundred titles. He became known first and foremost as a novelist and a journalist - in particular, as a reporter in three wars (First World War, Spanish Civil War and the Second World War). His articles on the Second World War have provoked intense controversies in West Germany, especially during the sixties.

The novel The Thaw gave its name to an entire era of Soviet politics, namely, the liberalization after the death of Joseph Stalin. Ehrenburg's travel writing also had great resonance, as did to an arguably greater extent his memoir People, Years, Life, which may be his best known and most discussed work. The Black Book, edited by him and Vassily Grossman, has special historical significance; detailing the genocide on Soviet citizens of Jewish ancestry, it is the first great documentary work on the Holocaust.

In addition, Ehrenburg wrote a succession of works of poetry.

Life and work

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Ilya Ehrenburg" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Ilya Ehrenburg was born in Kiev, Russian Empire to a Jewish family; his father was an engineer. Ehrenburg's family was not religiously affiliated; he came into contact with the religious practices of Judaism only through his maternal grandfather. Ehrenburg never joined any religious denomination, in spite of his later flirtation with Catholicism. He learned no Yiddish, although he edited the Black Book, which was written in Yiddish. He understood himself as a Russian, and later as a Soviet citizen, but left all his papers to Israel's Yad Vashem. He took strong public positions against antisemitism. He wrote in Russian even during his many years abroad.

When Ehrenburg was four years old, the family moved to Moscow, where his father had been hired as director of a brewery. At school, he met Nikolai Bukharin, who was two grades above him; the two remained friends until Bukharin's death during the Great Terror of 1938.

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1905, both Ehrenburg and Bukharin got involved in illegal activities of the Bolshevik organisation. In 1908, when Ehrenburg was seventeen years old, the tsarist secret police (Okhrana) arrested him for five months. He was beaten up and lost some teeth. Finally he was allowed to go abroad and chose Paris for his exile.

In Paris, he started to work in the Bolshevik organisation, meeting Vladimir Lenin and other prominent exiles. But soon he left these circles and the Communist Party. Ehrenburg became attached to the bohemian life in the Paris quarter of Montparnasse. He began to write poems, regularly visited the cafés of Montparnasse and got acquainted with a lot of artists, especially Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, and Amedeo Modigliani. Foreign writers whose works Ehrenburg translated included those of Francis Jammes.

During the First World War, Ehrenburg became a war correspondent for a St. Petersburg newspaper. He wrote a series of articles about the mechanized war that later on were also published as a book ("The Face of War"). His poetry now also concentrated on subjects of war and destruction, as in "On the Eve", his third lyrical book. Nikolai Gumilev, a famous symbolistic poet, wrote favourably about Ehrenburg's progress in poetry.

In 1917, after the revolution, Ehrenburg returned to Russia. At that time he tended to oppose the Bolshevik policy, being shocked by the constant atmosphere of violence. He wrote a poem called "Prayer for Russia" which compared the Storming of the Winter Palace to rape. In 1920 Ehrenburg went to Kiev where he experienced four different regimes in the course of one year: the Germans, the Cossacks, the Bolsheviks, and the White Army. After antisemitic pogroms, he fled to Koktebel on the Crimea peninsula where his old friend from Paris days, Maximilian Voloshin, had a house. Finally, Ehrenburg returned to Moscow, where he soon was arrested by the Cheka but freed in short time.

He became a Soviet cultural activist and journalist who spent much time abroad, as a writer and a propaganda agent for the Soviet government. As such his loyalty to Communism and to Stalin's regime never failed, not even during the great purges, although he knew too well what was happening inside the Soviet Union. He also never expressed criticism or uneasiness about the oppressive nature of the Soviet regime, the brutal suppression of political dissent, the forced collectivization or any other crimes perpetrated by the Soviet system. Until the end of his life he remained faithful to his Marxist and Leninist credo.

He wrote modernistic picaresque novels and short stories popular in the 1920s, often set in Western Europe (The Extraordinary Adventures of Julia Jurenito and his Disciples (1922), Thirteen Pipes). Ehrenburg continued to write philosophical poetry, using more freed rhythms than in the 1910s.

As a friend of many of the European Left, Ehrenburg was frequently allowed by Stalin to visit Europe and to campaign for peace and socialism. In 1936-39, he was a war journalist in the Spanish civil war, but also got involved directly in the military activities of the Republican camp.

World War II

Ehrenburg was active in war journalism throughout World War II. As a consequence, he is one of many Soviet writers, along with Konstantin Simonov and Aleksey Surkov, who have been accused by many of " their literary talents to the hate campaign" against Germans during World War II. His article "Kill" published in 1942 — when German troops were deeply within Soviet territory — became a widely publicized example of this campaign, along with the poem "Kill him!" by Simonov. In "Kill", Ehrenburg wrote: "We know all. We remember all. We have understood: Germans are not human. From now on the word "German" is the worst kind of curse. From now on the word "German" causes a rifle to discharge. We shall not talk. We shall kill. If you have not killed at least one German a day, that day will be wasted. If you think that your neighbor would kill a German, you haven't understood the threat. If you do not kill the German, he will kill you. If you don't kill a German, he will he will take your family and torture them in his damned Germany. If you cannot kill your German with a bullet, kill him with your bayonet. If there is calm on your part of the front, if you are waiting for the fighting, kill a German before combat. If you leave a German alive, the German will hang a Russian man and rape a Russian woman. If you kill one German, kill another - there is nothing more amusing for us than a German corpses. Do not count days; do not count miles. Count only the number of Germans you have killed. Kill a German - Your old mother asks you for that. Kill a German - your child asks you for that. Kill a German - your native land asks you for that." After criticism by Georgy Aleksandrov in Pravda in April 1945,, Ehrenburg responded that he never meant wiping out the German people, but only German aggressors who came to our soil with weapons, because "we are not Nazi" to fight with civilians. He wrote already in May 1942 : "The German soldier with weapon in hand is not a man for us, but a fascist. We hate him When the German soldier gives up his weapon and surrenders, we will not touch him with a finger - he will live.". Ehrenburg fell in disgrace at that time and it is estimated that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.

Ehrenburg was a prominent member of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

In 1942 Ehrenburg was a companion to Leland Stowe, an American journalist who traveled to Soviet front lines. In his book They Shall Not Sleep published in the USA in 1944 Stowe describes his interaction with Ehrenburg.

Postwar writings

In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled The Thaw that tested the limits of censorship in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. It portrayed a corrupted and despotic factory boss, a "little Stalin", and told the story of his wife, who increasingly feels estranged from him, and the views he represents. In the novel the spring thaw comes to represent a period of change in the characters' emotional journeys, and when the wife eventually leaves her husband this coincides with the melting of the snow. Thus the novel can be seen as a representation of the thaw, and the increased freedom of the writer after the 'frozen' political period under Stalin. In August 1954, Konstantin Simonov attacked The Thaw in articles published in Literaturnaya gazeta, arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state. The novel gave its name to the Khrushchev Thaw. Just prior to publishing the book, however, Ehrenburg received the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952.

Ehrenburg is particularly well known for his memoirs ("People, Years, Life"), which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. In this book Ehrenburg was the first legal Soviet author to mention positively a lot of names banned under Stalin, including the one of Marina Tsvetaeva. At the same time he disapproved of the Russian and Soviet intellectuals who had explicitly rejected Communism or Stalinism or defected to the West. He also criticized writers like Boris Pasternak, author of "Doctor Jivago", for not having been able to understand the course of history.

Ehrenburg's memoirs were criticized by the more conservative faction among the Soviet writers, concentrated around the journal Oktyabr'. For example, as the memoirs were published, Vsevolod Kochetov reflected on certain writers who are “burrowing in the rubbish heaps of their crackpot memories.”

For the contemporary reader though, the work appears to have a distinctly Marxist-Leninist ideological flavor characteristic to a Soviet-era official writer.

He was also active in publishing the works by Osip Mandelstam when the latter had been posthumously rehabilitated but still largely unacceptable for censorship. Together with Vasily Grossman, Ehrenburg edited The Black Book that contains documentary accounts by Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in the Soviet Union and Poland. Ehrenburg was also active as a poet till his last days, depicting the events of World War II in Europe, the Holocaust and the destinies of Russian intellectuals.

Death

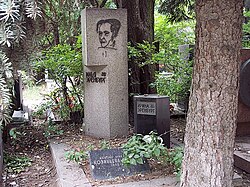

Ehrenburg died in 1967 of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where his gravestone is adorned with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend Pablo Picasso.

English translations

- The Tempering of Russia, Knopf, NY, 1944.

- European Crossroad: A Soviet Journalist In the Balkans, Knopf, NY, 1947.

- The Ninth Wave, Lawrence And Wishart, London, 1955.

- The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz, Polyglot Library, 1960.

- A Change of Season, (includes The Thaw and its sequel The Spring), Knopf, NY, 1962.

- Chekhov, Stendhal and Other Essays, Knopf, NY, 1963.

- The Second Day, Raduga Publishers, Moscow, 1984.

- Life of the Automobile, Serpent's Tail, 1999.

- The Fall of Paris, Simon Publications, 2002.

- The Storm, University Press of the Pacific, 2003.

See also

References

- ^ Orlando Figes The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, 2007, ISBN 00805074619 , page 414. Cite error: The named reference "Figes" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- (Text is found in Ilya Ehrenburg's book Vojna (The war) (Moscow, 1942-43)

- Original text in Russian

- Article in Russian original

- Ehrenburg's answer (Russian)

- "On Hatred", May 1942

- Joshua Rubenstein: Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. 1st Paperback Ed., University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa (Alabama/USA) 1999 (= Judaic Studies Series), ISBN 0-8173-0963-2

- Carola Tischler: Die Vereinfachungen des Genossen Ehrenburg. Eine Endkriegs- und eine Nachkriegskontroverse. In: Elke Scherstjanoi (Hrsg.): Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland. Briefe von der Front (1945) und historische Analysen. Texte und Materialien zur Zeitgeschichte, Bd. 14. K.G. Saur, München 2004, S. 326–339, ISBN 3-598-11656-X, p. 336-

- http://books.google.com/books?id=W-jcOgCc8x0C&pg=PA222&dq=vsevolod+kochetov&hl=en&ei=pAB1TLLAC4jeOKPvhYMH&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CEcQ6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=vsevolod%20kochetov&f=false

External links

- Poems by Ilya Erenburg (English Translations)

- A poem in verse translation by Alexander Givental (UC Berkeley)

- The Black Book at jewishgen.org

- Tangled Loyalties, the 'definitive' Ehrenburg biography by Joshua Rubenstein at the book's home on the web

- Long biography, includes quote above

- Article in The Columbia Encyclopedia

- Brief page on The Thaw

- Marevna, "Homage to Friends from Montparnasse" (1962) Top left to right: Diego Rivera, Ilya Ehrenburg, Chaim Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, his wife Jeanne Hébuterne, Max Jacob, gallery owner Leopold Zborowski . Bottom left to right: Marevna, hers and Diego Rivera's daughter Marika, (Amedeo Modigliani), Moise Kisling.

- Olga Carlisle (Summer–Fall 1961). Ilya Ehrenburg, The Art of Fiction No. 26.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Excerpts from "The Storm" in English. From SovLit.net

- Tribute to Ehrenburg by Aleksandr Tvardovsky in English. From SovLit.net

- 1891 births

- 1967 deaths

- People from Kiev

- Ukrainian Jews

- Bolsheviks

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Jewish poets

- Memoirists

- Old Bolsheviks

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Russian novelists

- Russian people of the Spanish Civil War

- Russian poets

- Russian writers

- Russian communists

- Soviet Jews

- Soviet novelists

- Stalin Prize winners

- Cancer deaths in the Soviet Union

- Deaths from prostate cancer

- Deaths from bladder cancer

- Soviet people of the Spanish Civil War