| Revision as of 17:15, 3 June 2013 editKARGOSEARCH2 (talk | contribs)9 edits →Modern period← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:26, 3 June 2013 edit undoGoethean (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users40,563 edits Undid revision 558155588 by KARGOSEARCH2 (talk)Next edit → | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

| ===Modern period=== | ===Modern period=== | ||

| British missionary ] According to Brian Pennington, Ward's book "became a centerpiece in the British construction of Hinduism and in the political and economic domination of the subcontinent."<ref name="Pennington" /> In 1825, however, ]'s work on the ] sect of South India attempted to refute popular British notions that the lingam graphically represented a human organ and that it aroused erotic emotions in its devotees.<ref name="Pennington">p132</ref> | British missionary ] criticized the worship of the lingam (along with virtually all other Indian religious rituals) in his influential 1815 book ''A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos'', calling it "the last state of degradation to which human nature can be driven", and stating that its symbolism was "too gross, even when refined as much as possible, to meet the public eye." According to Brian Pennington, Ward's book "became a centerpiece in the British construction of Hinduism and in the political and economic domination of the subcontinent."<ref name="Pennington" /> In 1825, however, ]'s work on the ] sect of South India attempted to refute popular British notions that the lingam graphically represented a human organ and that it aroused erotic emotions in its devotees.<ref name="Pennington">p132</ref> | ||

| Monier-Williams wrote in ''Brahmanism and Hinduism'' that the symbol of ''linga'' is "never in the mind of a Saiva (or Siva-worshipper) connected with indecent ideas, nor with sexual love."<ref>{{cite book|last=Carus|first=Paul |title=The History of the Devil|publisher=Forgotten Books|pages=82|url=http://books.google.com/?id=79KEpjUgX5IC&pg=PA82 | isbn=978-1-60506-556-4|year=1969}}</ref> According to Jeaneane Fowler, the linga is "a ] symbol which represents the potent energy which is manifest in the cosmos."<ref name="Fowler"/> Some scholars, such as David James Smith, believe that throughout its history the lingam has represented the phallus; others, such as N. Ramachandra Bhatt, believe the phallic interpretation to be a later addition.<ref name="djsmith">''Hinduism and Modernity'' By David James Smith p. 119 ></ref> M. K. V. Narayan distinguishes the Siva-linga from ] representations of Siva, and notes its absence from ] literature, and its interpretation as a phallus in ] sources.<ref>Flipside of Hindu symbolism, by M. K. V. Narayan, pp. 86–87, </ref> | Monier-Williams wrote in ''Brahmanism and Hinduism'' that the symbol of ''linga'' is "never in the mind of a Saiva (or Siva-worshipper) connected with indecent ideas, nor with sexual love."<ref>{{cite book|last=Carus|first=Paul |title=The History of the Devil|publisher=Forgotten Books|pages=82|url=http://books.google.com/?id=79KEpjUgX5IC&pg=PA82 | isbn=978-1-60506-556-4|year=1969}}</ref> According to Jeaneane Fowler, the linga is "a ] symbol which represents the potent energy which is manifest in the cosmos."<ref name="Fowler"/> Some scholars, such as David James Smith, believe that throughout its history the lingam has represented the phallus; others, such as N. Ramachandra Bhatt, believe the phallic interpretation to be a later addition.<ref name="djsmith">''Hinduism and Modernity'' By David James Smith p. 119 ></ref> M. K. V. Narayan distinguishes the Siva-linga from ] representations of Siva, and notes its absence from ] literature, and its interpretation as a phallus in ] sources.<ref>Flipside of Hindu symbolism, by M. K. V. Narayan, pp. 86–87, </ref> | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

| II </ref><ref>Jeffrey Kripal, ''Kali's Child'' 159–163</ref> At the Paris Congress of the History of Religions in 1900, Ramakrishna's follower ] argued that the ''Shiva-Linga'' had its origin in the idea of the ''Yupa-]'' or ''Skambha''—the sacrificial post, idealized in Vedic ritual as the symbol of the Eternal ].<ref name="E. U. Harding"/><ref name="paris_congress"/><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1086/472718 | author = Nathaniel Schmidt | title = The Paris Congress of the History of Religion | journal = The Biblical World | volume = 16 | issue = 6 | pages = 447–450 | year = Dec, 1900 | jstor = 3136952}}</ref> This was in response to a paper read by Gustav Oppert, a German ], who traced the origin of the ''Shalagrama-Shila'' and the ''Shiva-Linga'' to phallicism.<ref>{{cite book|last=Sen|first=Amiya P.|title=The Indispensable Vivekananda|publisher=Orient Blackswan|year=2006|pages=25–26|chapter=Editor's Introduction | quote = During September–October 1900, he was a delegate to the Religious Congress at Paris, though oddly, the organizers disallowed discussions on any particular religious tradition. It was rumoured that his had come about largely through the pressure of the Catholic Church, which worried over the 'damaging' effects of Oriental religion on the Christian mind. Ironically, this did not stop Western scholars from making surreptitious attacks on traditional Hinduism. Here, Vivekananda strongly contested the suggestion made by the German Indologist Gustav Oppert that the Shiva Linga and the Salagram Shila, stone icons representing the gods Shiva and Vishnu respectively, were actually crude remnants of phallic worship.}}</ref> According to Vivekananda, the explanation of the ''Shalagrama-Shila'' as a phallic emblem was an imaginary invention. Vivekananda argued that the explanation of the ''Shiva-Linga'' as a phallic emblem was brought forward by the most thoughtless, and was forthcoming in India in her most degraded times, those of the downfall of ].<ref name="paris_congress"/> | II </ref><ref>Jeffrey Kripal, ''Kali's Child'' 159–163</ref> At the Paris Congress of the History of Religions in 1900, Ramakrishna's follower ] argued that the ''Shiva-Linga'' had its origin in the idea of the ''Yupa-]'' or ''Skambha''—the sacrificial post, idealized in Vedic ritual as the symbol of the Eternal ].<ref name="E. U. Harding"/><ref name="paris_congress"/><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1086/472718 | author = Nathaniel Schmidt | title = The Paris Congress of the History of Religion | journal = The Biblical World | volume = 16 | issue = 6 | pages = 447–450 | year = Dec, 1900 | jstor = 3136952}}</ref> This was in response to a paper read by Gustav Oppert, a German ], who traced the origin of the ''Shalagrama-Shila'' and the ''Shiva-Linga'' to phallicism.<ref>{{cite book|last=Sen|first=Amiya P.|title=The Indispensable Vivekananda|publisher=Orient Blackswan|year=2006|pages=25–26|chapter=Editor's Introduction | quote = During September–October 1900, he was a delegate to the Religious Congress at Paris, though oddly, the organizers disallowed discussions on any particular religious tradition. It was rumoured that his had come about largely through the pressure of the Catholic Church, which worried over the 'damaging' effects of Oriental religion on the Christian mind. Ironically, this did not stop Western scholars from making surreptitious attacks on traditional Hinduism. Here, Vivekananda strongly contested the suggestion made by the German Indologist Gustav Oppert that the Shiva Linga and the Salagram Shila, stone icons representing the gods Shiva and Vishnu respectively, were actually crude remnants of phallic worship.}}</ref> According to Vivekananda, the explanation of the ''Shalagrama-Shila'' as a phallic emblem was an imaginary invention. Vivekananda argued that the explanation of the ''Shiva-Linga'' as a phallic emblem was brought forward by the most thoughtless, and was forthcoming in India in her most degraded times, those of the downfall of ].<ref name="paris_congress"/> | ||

| According to ], the view that the Shiva lingam represents the phallus is a mistake;<ref name="Sivananda 1996"/> The same sentiments have also been expressed by ] in 1840.<ref name="hh.w">{{cite book|last=Wilson|first=HH|title=Vishnu Purana|publisher=John Murray, London, 2005|pages=xli–xlii|chapter=Classification of Puranas}}</ref> <ref name="Isherwood 48">{{cite book | last = Isherwood | first = Christopher | authorlink = Christopher Isherwood | title = Ramakrishna and his disciples | chapter = Early days at Dakshineswar | pages = 48 }}</ref> The Britannica encyclopedia entry on ''lingam'' also notes that the lingam is not considered to be a phallic symbol;<ref name="Britannica">{{Cite web | title = lingam | publisher = Encyclopædia Britannica | year = 2010 | url = http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/342336/lingam | quote = | According to ], the view that the Shiva lingam represents the phallus is a mistake;<ref name="Sivananda 1996"/> The same sentiments have also been expressed by ] in 1840.<ref name="hh.w">{{cite book|last=Wilson|first=HH|title=Vishnu Purana|publisher=John Murray, London, 2005|pages=xli–xlii|chapter=Classification of Puranas}}</ref> The novelist ] also addresses the interpretation of the ''linga'' as a sex symbol.<ref name="Isherwood 48">{{cite book | last = Isherwood | first = Christopher | authorlink = Christopher Isherwood | title = Ramakrishna and his disciples | chapter = Early days at Dakshineswar | pages = 48 }}</ref> The Britannica encyclopedia entry on ''lingam'' also notes that the lingam is not considered to be a phallic symbol;<ref name="Britannica">{{Cite web | title = lingam | publisher = Encyclopædia Britannica | year = 2010 | url = http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/342336/lingam | quote = Since the late 19th century some scholars have interpreted the lingam and the yoni to be representations of the male and female sexual organs. To practicing Hindus, however, the two together are a reminder that the male and female principles are inseparable and that they represent the totality of all existence.}}</ref> | ||

| ], an American scholar of the history of religions, states:{{quote|For Hindus, the phallus in the background, the archetype (if I may use the word in its ], indeed ], and non-] sense) of which their own penises are manifestations, is the phallus (called the ''lingam'') of the god Siva, who inherits much of the mythology of ] (O'Flaherty, 1973). The lingam appeared, separate from the body of Siva, on several occasions... On each of these occasions, Siva's wrath was appeased when gods and humans promised to worship his lingam forever after, which, in India they still do. Hindus, for instance, will argue that the lingam has nothing whatsoever to do with the male sexual organ, an assertion blatantly contradicted by the material.<ref name="Wendy Doniger">{{Cite book|author=Doniger, Wendy|title=When a Lingam is Just a Good Cigar: Psychoanalysis and Hindu Sexual Fantasies|journal=The Psychoanalytic Study of Society, Vol 18.|editor=Boyer, L. Bryce; Boyer, Ruth M.; Sonnenburg, Stephen M|publisher=Routledge|year=1993|url=http://books.google.com/?id=urkQzMCLcE0C&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-88163-161-6|accessdate=2009-06-22|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref>}} | ], an American scholar of the history of religions, states:{{quote|For Hindus, the phallus in the background, the archetype (if I may use the word in its ], indeed ], and non-] sense) of which their own penises are manifestations, is the phallus (called the ''lingam'') of the god Siva, who inherits much of the mythology of ] (O'Flaherty, 1973). The lingam appeared, separate from the body of Siva, on several occasions... On each of these occasions, Siva's wrath was appeased when gods and humans promised to worship his lingam forever after, which, in India they still do. Hindus, for instance, will argue that the lingam has nothing whatsoever to do with the male sexual organ, an assertion blatantly contradicted by the material.<ref name="Wendy Doniger">{{Cite book|author=Doniger, Wendy|title=When a Lingam is Just a Good Cigar: Psychoanalysis and Hindu Sexual Fantasies|journal=The Psychoanalytic Study of Society, Vol 18.|editor=Boyer, L. Bryce; Boyer, Ruth M.; Sonnenburg, Stephen M|publisher=Routledge|year=1993|url=http://books.google.com/?id=urkQzMCLcE0C&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-88163-161-6|accessdate=2009-06-22|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref>}} | ||

Revision as of 17:26, 3 June 2013

"Linga" redirects here. For other uses, see Linga (disambiguation). "Shivling" redirects here. For the mountain, see Shivling (Garhwal Himalaya).

The lingam (also, linga, ling, Shiva linga, Shiv ling, Sanskrit लिङ्गं, liṅgaṃ, meaning "mark", "sign", "inference" or) is a representation of the Hindu deity Shiva used for worship in temples. The lingam is often represented alongside the yoni, a symbol of the goddess or of Shakti, female creative energy. The union of lingam and yoni represents the "indivisible two-in-oneness of male and female, the passive space and active time from which all life originates". The lingam and the yoni have been interpreted as the male and female sexual organs since the end of the 19th century by some scholars, while to practising Hindus they stand for the inseparability of the male and female principles and the totality of creation.

Shiva Lingam

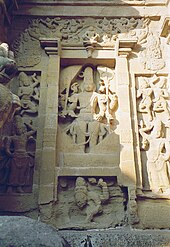

Emerging of Lord Shiva or Maheshwara from cosmic flame is Lingodbhava also pictured as Shiva emerging from the Lingam – the cosmic pillar of fire. According to Linga Puran, Shiva लिङ्गं liṅgaṃ Shiva Lingam or Shiva Pindi has been interpreted as a symbol representation Formless, Universe Bearer & a Complete One, the oval shaped stone is resembling mark of the Universe and bottom base as the Supreme Power holding the entire Universe in it. Shiva Purana describes the origin of the lingam as the endless pillar (Stambha). The Linga Purana also supports the interpretation as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva. The word Lingam has many meanings.

The Hindu scripture Shiva Purana describes the worship of the lingam as originating in the loss and recovery of Shiva's phallus, though it also describes the origin of the lingam as the beginning-less and endless pillar (Stambha). The Linga Purana also supports the latter interpretation as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva. Shiva is pictured as Lingodbhava, emerging from the Lingam – the cosmic fire pillar – proving his superiority over gods Brahma and Vishnu.

Definition

The Sanskrit term लिङ्गं liṅgaṃ, transliterated as linga, has diverse meaning ranging from gender and sex to philosophic and religions to uses in common language, such as a mark, sign or characteristic. Vaman Shivram Apte's Sanskrit dictionary provides many definitions:

- A mark, sign, token, an emblem, a badge, symbol, distinguishing mark, characteristic;

- A symptom, mark of disease

- A means of proof, a proof, evidence

- In logic, the hetu or middle term in a syllogism

- In grammar, gender

- The image of a god, an idol

- One of the relations or indications which serve to fix the meaning of a word in any particular passage

- In Vedānta philosophy, the subtle frame or body, the indestructible original of the gross or visible body

- A spot or stain

- The nominal base, the crude form of a noun

- In Sāk philosophy, Pradhāna or Prakriti

- The effect or product of evolution from a primary cause and also as the producer

- Inference, conclusion

History

Origin

Anthropologist Christopher John Fuller conveys that although most sculpted images (murtis) are anthropomorphic, the aniconic Shiva Linga is an important exception. Some believe that linga-worship was a feature of indigenous Indian religion.

There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda which praises a pillar (Sanskrit: stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga-worship. Some associate Shiva-Linga with this Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post. In that hymn a description is found of the beginningless and endless Stambha or Skambha and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. As afterwards the Yajna (sacrificial) fire, its smoke, ashes and flames, the soma plant and the ox that used to carry on its back the wood for the Vedic sacrifice gave place to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted-hair, his blue throat and the riding on the bull of the Shiva. The Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga. In the Linga Purana the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories, meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).

Historical period

According to Saiva Siddhanta, which was for many centuries the dominant school of Shaiva theology and liturgy across the Indian subcontinent (and beyond it in Cambodia), the linga is the ideal substrate in which the worshipper should install and worship the five-faced and ten-armed Sadāśiva, the form of Shiva who is the focal divinity of that school of Shaivism.

The oldest example of a lingam which is still used for worship is in Gudimallam. According to Klaus Klostermaier, it is clearly a phallic object, and dates to the 2nd century BC. A figure of Shiva is carved into the front of the lingam.

Modern period

British missionary William Ward criticized the worship of the lingam (along with virtually all other Indian religious rituals) in his influential 1815 book A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos, calling it "the last state of degradation to which human nature can be driven", and stating that its symbolism was "too gross, even when refined as much as possible, to meet the public eye." According to Brian Pennington, Ward's book "became a centerpiece in the British construction of Hinduism and in the political and economic domination of the subcontinent." In 1825, however, Horace Hayman Wilson's work on the lingayat sect of South India attempted to refute popular British notions that the lingam graphically represented a human organ and that it aroused erotic emotions in its devotees.

Monier-Williams wrote in Brahmanism and Hinduism that the symbol of linga is "never in the mind of a Saiva (or Siva-worshipper) connected with indecent ideas, nor with sexual love." According to Jeaneane Fowler, the linga is "a phallic symbol which represents the potent energy which is manifest in the cosmos." Some scholars, such as David James Smith, believe that throughout its history the lingam has represented the phallus; others, such as N. Ramachandra Bhatt, believe the phallic interpretation to be a later addition. M. K. V. Narayan distinguishes the Siva-linga from anthropomorphic representations of Siva, and notes its absence from Vedic literature, and its interpretation as a phallus in Tantric sources.

Ramakrishna practiced Jivanta-linga-puja, or "worship of the living lingam". At the Paris Congress of the History of Religions in 1900, Ramakrishna's follower Swami Vivekananda argued that the Shiva-Linga had its origin in the idea of the Yupa-Stambha or Skambha—the sacrificial post, idealized in Vedic ritual as the symbol of the Eternal Brahman. This was in response to a paper read by Gustav Oppert, a German Orientalist, who traced the origin of the Shalagrama-Shila and the Shiva-Linga to phallicism. According to Vivekananda, the explanation of the Shalagrama-Shila as a phallic emblem was an imaginary invention. Vivekananda argued that the explanation of the Shiva-Linga as a phallic emblem was brought forward by the most thoughtless, and was forthcoming in India in her most degraded times, those of the downfall of Buddhism.

According to Swami Sivananda, the view that the Shiva lingam represents the phallus is a mistake; The same sentiments have also been expressed by H. H. Wilson in 1840. The novelist Christopher Isherwood also addresses the interpretation of the linga as a sex symbol. The Britannica encyclopedia entry on lingam also notes that the lingam is not considered to be a phallic symbol;

Wendy Doniger, an American scholar of the history of religions, states:

For Hindus, the phallus in the background, the archetype (if I may use the word in its Eliadean, indeed Bastianian, and non-Jungian sense) of which their own penises are manifestations, is the phallus (called the lingam) of the god Siva, who inherits much of the mythology of Indra (O'Flaherty, 1973). The lingam appeared, separate from the body of Siva, on several occasions... On each of these occasions, Siva's wrath was appeased when gods and humans promised to worship his lingam forever after, which, in India they still do. Hindus, for instance, will argue that the lingam has nothing whatsoever to do with the male sexual organ, an assertion blatantly contradicted by the material.

However, Professor Doniger clarified her viewpoints in a later book, The Hindus: An Alternative History, by noting that some texts treat the linga as an aniconic pillar of light or an as an abstract symbol of God with no sexual reference and comments on the varying interpretations of the linga from phallic to abstract.

According to Hélène Brunner, the lines traced on the front side of the linga, which are prescribed in medieval manuals about temple foundation and are a feature even of modern sculptures, appear to be intended to suggest a stylised glans, and some features of the installation process seem intended to echo sexual congress. Scholars like S. N.Balagangadhara have disputed the sexual meaning of lingam.

Naturally occurring lingams

An ice lingam at Amarnath in the western Himalayas forms every winter from ice dripping on the floor of a cave and freezing like a stalagmite. It is very popular with pilgrims.

Shivling (6543m) is also a mountain in Uttarakhand (the Garhwal region of Himalayas). It arises as a sheer pyramid above the snout of the Gangotri Glacier. The mountain resembles a Shiva linga when viewed from certain angles, especially when travelling or trekking from Gangotri to Gomukh as a part of a traditional Hindu pilgrimage.

See also

- Axis mundi

- Banalinga

- Danda

- Dhyanalinga

- Fascinus

- Herma

- Hindu iconography

- Lingayatism

- Mukhalingam

- Pancharamas

- Saligram

Notes

- ^ Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary

- A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary

- ^ Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, by Jeanne Fowler, pgs. 42–43, In traditional Indian society, the linga is rather seen as a symbol of the energy and potentiality of the God.

- ^ Mudaliyar, Sabaratna. "Lecture on the Shiva Linga". Malaysia Hindu Dharma Mamandram. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "lingam". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010.

Since the late 19th century some scholars have interpreted the lingam and the yoni to be representations of the male and female sexual organs. To practicing Hindus, however, the two together are a reminder that the male and female principles are inseparable and that they represent the totality of all existence.

- Isherwood, Christopher (1983). Ramakrishna and His Disciples. Early days at Dakshineswar: Vedanta Press,U.S. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-87481-037-0.

- Sivananda (1996 (web edn. 2000)). Lord Siva and His Worship. Worship of Siva Linga: The Divine Life Trust Society. ISBN 81-7052-025-8.

The popular belief is that the Siva Lingam represents the phallus or the virile organ, the emblem of the generative power or principle in nature. This is not only a serious mistake, but also a grave blunder. In the post-Vedic period, the Linga became symbolical of the generative power of the Lord Siva. Linga is the differentiating mark. It is certainly not the sex-mark.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Subramuniyaswami, Sivaya. "Satguru". Dancing With Shiva. Himalayan Academy. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- Zimmer, Heinrich Robert (1946). Campbell, Joseph (ed.). Myths and symbols in Indian art and civilization. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-691-01778-6.

But the basic and most common object of worship in Shiva shrines is the phallus or lingam.

- Jansen, Eva Rudy (2003) . The book of Hindu imagery: gods, manifestations and their meaning. Binkey Kok Publications. pp. 46, 119. ISBN 90-74597-07-6.

- ^ Blurton, T. R. (1992). "Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava". Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press). British Museum site. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Sivananda, Swami (1996). "Worship of Siva Linga". Lord Siva and His Worship. The Divine Life Trust Society.

- ^ Chaturvedi. Shiv Purana (2006 ed.). Diamond Pocket Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-7182-721-3.

- ^ "The linga Purana". astrojyoti. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

. It was almost as if the linga had emerged to settle Brahma and Vishnu's dispute. The linga rose way up into the sky and it seemed to have no beginning or end.

- Peter Heehs, Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience 210-213 NYU Press, Sep, 2002

- ^ Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-81-208-1450-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions". The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol. Vol.4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1957–59). The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary (Revised and enlarged ed.). Poona: Prasad Prakashan. p. 1366.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and society in India, pg. 58 at Books.Google.com

- ^ N. K. Singh, Encyclopaedia of Hinduism p. 1567

- Dominic Goodall, Nibedita Rout, R. Sathyanarayanan, S.A.S. Sarma, T. Ganesan and S. Sambandhasivacarya, The Pañcāvaraṇastava of Aghoraśivācārya: A twelfth-century South Indian prescription for the visualisation of Sadāśiva and his retinue, Pondicherry, French Institute of Pondicherry and Ecole française d'Extréme-Orient, 2005, p.12.

- Klaus Klostermaier, A Survey of Hinduism 2007 SUNY Press p111

- Hinduism and the Religious Arts By Heather Elgood p. 47

- ^ p132

- Carus, Paul (1969). The History of the Devil. Forgotten Books. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-60506-556-4.

- Hinduism and Modernity By David James Smith p. 119 >

- Flipside of Hindu symbolism, by M. K. V. Narayan, pp. 86–87, Books.Google.com

- Ramakrishna Kathamrita Section XV Chapter II

- Jeffrey Kripal, Kali's Child 159–163

- Nathaniel Schmidt (Dec, 1900). "The Paris Congress of the History of Religion". The Biblical World. 16 (6): 447–450. doi:10.1086/472718. JSTOR 3136952.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Sen, Amiya P. (2006). "Editor's Introduction". The Indispensable Vivekananda. Orient Blackswan. pp. 25–26.

During September–October 1900, he was a delegate to the Religious Congress at Paris, though oddly, the organizers disallowed discussions on any particular religious tradition. It was rumoured that his had come about largely through the pressure of the Catholic Church, which worried over the 'damaging' effects of Oriental religion on the Christian mind. Ironically, this did not stop Western scholars from making surreptitious attacks on traditional Hinduism. Here, Vivekananda strongly contested the suggestion made by the German Indologist Gustav Oppert that the Shiva Linga and the Salagram Shila, stone icons representing the gods Shiva and Vishnu respectively, were actually crude remnants of phallic worship.

- Wilson, HH. "Classification of Puranas". Vishnu Purana. John Murray, London, 2005. pp. xli–xlii.

- Isherwood, Christopher. "Early days at Dakshineswar". Ramakrishna and his disciples. p. 48.

- Doniger, Wendy (1993). Boyer, L. Bryce; Boyer, Ruth M.; Sonnenburg, Stephen M (ed.). When a Lingam is Just a Good Cigar: Psychoanalysis and Hindu Sexual Fantasies. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-88163-161-6. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Hélène Brunner, The sexual Aspect of the linga Cult according to the Saiddhāntika Scriptures, pp.87–103 in Gerhard Oberhammer's Studies in Hinduism II, Miscellanea to the Phenomenon of Tantras, Vienna, Verlag der oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1998.

- Balagangadhara, S. N. (2007). Invading the Sacred. Rupa & Co. pp. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-291-1182-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)

References

- Basham, A. L. The Wonder That Was India: A survey of the culture of the Indian Sub-Continent before the coming of the Muslims, Grove Press, Inc., New York (1954; Evergreen Edition 1959).

- Schumacher, Stephan and Woerner, Gert. The encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and religion, Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, Hinduism, Shambhala, Boston, (1994) ISBN 0-87773-980-3

- Ram Karan Sharma. Śivasahasranāmāṣṭakam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Śiva. With Introduction and Śivasahasranāmākoṣa (A Dictionary of Names). (Nag Publishers: Delhi, 1996). ISBN 81-7081-350-6. This work compares eight versions of the Śivasahasranāmāstotra. The preface and introduction Template:En icon by Ram Karan Sharma provide an analysis of how the eight versions compare with one another. The text of the eight versions is given in Sanskrit.

Further reading

- Danielou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 222–231. ISBN 0-89281-354-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Versluis, Arthur (2008), The Secret History of Western Sexual Mysticism: Sacred Practices and Spiritual Marriage, Destiny Books, ISBN 978-1-59477-212-2

External links

| Shaivism | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||||||

| Deities |  | ||||||||||

| Texts | |||||||||||

| Mantra/Stotra | |||||||||||

| Traditions | |||||||||||

| Festivals and observances | |||||||||||

| Shiva temples |

| ||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||

| Worship in Hinduism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main topics | |||||||

| Rituals |

| ||||||

| Mantras | |||||||

| Objects | |||||||

| Materials | |||||||

| Instruments | |||||||

| Iconography | |||||||

| Places | |||||||

| Roles | |||||||

| Sacred animals | |||||||

| Sacred plants |

| ||||||

| See also | |||||||