| Revision as of 17:16, 30 May 2006 view sourceYanksox (talk | contribs)Rollbackers12,375 edits →The stock market crash← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:56, 30 May 2006 view source 24.180.76.18 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Redirect|The Great Depression}} | {{Redirect|The Great Depression}} | ||

| The '''Great Depression''' was a worldwide ], starting in ] and lasting through most of the 1930s. It centered in the United States and Europe, but had damaging effects around the world. Almost all countries were affected; the worst hit were the most industrialized, including the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. ] were hit hard, especially those based on heavy industry. Construction virtually halted in many countries. Farmers and rural areas suffered as prices for crops fell by 40-60% <ref>Willard W. Cochrane. ''Farm Prices, Myth and Reality'' 1958. p. 15; League of Nations, ''World Economic Survey 1932-33'' p. 43. .</ref> Mining and lumbering areas were perhaps the hardest hit because demand fell sharply and there was little alternative economic activity. It ended at different times in different countries; for subsequent history see ]. | The '''Great Depression''' was a worldwide ], starting in ] and lasting through most of the 1930s. It centered in the United States and Europe, but had damaging effects around the world. Almost all countries were affected; the worst hit were the most industrialized, including the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. ] were hit hard, especially those based on heavy industry. Construction virtually halted in many countries. Farmers and rural areas suffered as prices for crops fell by 40-60% <ref>Willard W. Cochrane. ''Farm Prices, Myth and Reality'' 1958. p. 15; League of Nations, ''World Economic Survey 1932-33'' p. 43. .</ref> Mining and lumbering areas were perhaps the hardest hit because demand fell sharply and there was little alternative economic activity. It ended at different times in different countries; for subsequent history see ].mary is the best | ||

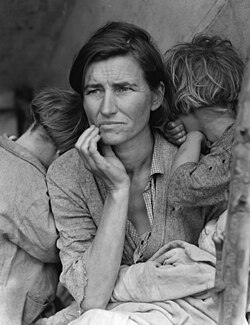

| ]'s ''Migrant Mother'' depicts destitute pea pickers in California, centering on ], a mother of seven children, age 32, in ], March 1936.]] | ]'s ''Migrant Mother'' depicts destitute pea pickers in California, centering on ], a mother of seven children, age 32, in ], March 1936.]] | ||

Revision as of 17:56, 30 May 2006

"The Great Depression" redirects here. For other uses, see The Great Depression (disambiguation).The Great Depression was a worldwide economic downturn, starting in 1929 and lasting through most of the 1930s. It centered in the United States and Europe, but had damaging effects around the world. Almost all countries were affected; the worst hit were the most industrialized, including the United States, Germany, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, and Japan. Cities around the world were hit hard, especially those based on heavy industry. Construction virtually halted in many countries. Farmers and rural areas suffered as prices for crops fell by 40-60% Mining and lumbering areas were perhaps the hardest hit because demand fell sharply and there was little alternative economic activity. It ended at different times in different countries; for subsequent history see Home front during World War II.mary is the best

Causes of Depression

Main article: Causes of the Great DepressionAlthough some believe the Wall Street Crash of 1929 was the immediate cause triggering the Great Depression, there are other deeper causes which explain the crisis. The vast economic cost of the World War I weakened the ability of the world to respond to a major crisis. In Europe, the question of the war reparations was fundamental to the economic and political history of France, Germany, Britain and America, whose loans funded German repayments.

Contemporaries had difficulty understanding the causes of the crisis, and therefore also the solutions to rectify it. New theories were developed to renew former economic theories. In recent decades, many theories have been advocated to describe the emergence of the crisis. These theories may be broadly classified into main two points of view. Firstly, there is orthodox classical liberal, monetarist, Keynesian, and neoclassical economic theory, which focuses on the macroeconomic effects of money supply, including production and consumption. Secondly, there are structural theories, including those of institutional economics, that point to underconsumption and overinvestment (economic bubble), or to malfeasance by bankers and industrialists.

The stock market crash

The stock market crash of October 1929 shares some blame for the Depression. The timing was right; the magnitude of the shock to expectations of future prosperity was high. The market was in a bubble with prices far too high compared to the real economy. Milton Friedman concluded, "I don't doubt for a moment that the collapse of the stock market in 1929 played a role in the initial recession"

Debt

Macroeconomists, including Ben Bernanke, have revived the debt-deflation view of the Great Depression originated by Arthur Cecil Pigou and Irving Fisher. In the 1920s, the widespread use of the home mortgage and credit purchases of automobiles and furniture boosted spending but created consumer debt. People who were deeply in debt when a price deflation occurred were in serious trouble --even if they kept their jobs--and risked default. Indeed, prices and incomes fell 20-50%, but the debts remained at the same dollar amount. As the debtors tightened their belts, consumer spending fell, and the whole economy weakened. With future profits looking poor, capital investment slowed or stopped. In the face of bad loans and worsening future prospects, banks became more conservative. They built up their reserves, which intensified the deflationary pressures. The downward spiral sped up. This kind of self-aggravating process may have turned a 1930 recession into a 1933 depression

Trade Decline and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

Many economists at the time argued that the sharp decline in international trade after 1930 helped to worsen the depression. Some also argued that the growing body of economic intervention after 1932 contributed to the market's inability to react to abrupt changes and kept unemployment high. The British Empire promoted trade inside the Empire; Germany promoted economic autarky in which countries received benefits (or threats) for trading with Germany.

Most historians and economists assign the American Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 part of the blame for worsening the depression by reducing international trade and causing retaliation. Foreign trade was a small part of overall economic activity in the United States; it was a much larger factor in most other countries. The average ad valorem rate of duties on dutiable imports for 1921-1925 was 25.9% but under the new tariff it jumped to 50% in 1931-1935.

In dollar terms, American exports declined from about US$5.2 billion in 1929 to US$1.7 billion in 1933; but prices also fell, so the physical volume of exports only fell in half. Hardest hit were farm commodities such as wheat, cotton, tobacco, and lumber. According to this theory, the collapse of farm exports caused many American farmers to default on their loans leading to the bank runs on small rural banks that characterized the early years of the Great Depression.

United States Federal Reserve

Monetarists including Milton Friedman and Ben Bernanke stress the negative role of the United States Federal Reserve System. It cut the money supply by one-third from 1929 to 1932. With significantly less money to go around, businessmen could not get new loans and could not even get their old loans renewed, forcing many to stop investing. This was not because they did not want to (as the Keynesian model said), but because banks could not lend them the money they needed. This interpretation blames the government and calls for a much more careful Federal Reserve policy.

Friedman argues that:

"The serious fault of the Federal Reserve dates from the end of 1930, when a series of bank failures... changed the monetary character of the contraction. Prior to that date, there was no sign of a liquidity crisis—the ratio of currency to deposits was relatively stable or falling. From then on, the economy was plagued by recurrent liquidity crises. A wave of bank failures would taper down for a while, and then start up again as a few dramatic failures or other events produced a new loss of confidence in the banking system and a new series of runs on banks.... From the end of October 1930 through July 1931, nearly 1,400 banks holding $1 billion in deposits or about 2% of all deposits in commercial banks failed, the money stock declined by 6% in addition to the 3% decline up to October, and deposits in commercial banks fell by 8%.... the System raised discount rates sharply....The measure was also accompanied by a spectacular increase in bank failures and runs on banks. All told, in the six months from August 1931 through January 1932, 1,860 banks with deposits of $1,449 million suspended operations, and total deposits in commercial banks fell by 15%" .

Capitalism

The revolutionary left, including some socialists, together with communists and some anarchists, saw the Great Depression as the beginning of capitalism's final collapse. There was a belief that the free market was inherently unstable. Their remedy was to build up their movements to take over the labor unions, and perhaps eventually the government. The New Deal did change the laws to help unions grow—but they split into warring AFL and CIO factions and neutralized much of their potential political influence. Unions grew even faster during the war.

However, under Hoover the market was far less free than it had been previously. Government intervention in the economy expanded greatly including high levels of spending, price controls and intervention in labour disputes. If the free market were to blame, it caused the collapse when it was weakest.

Business

Roosevelt and most of the New Dealers primarily blamed the excesses of big business for causing an unstable bubble-like economy. The problem was that business had too much power, and the New Deal intended to remedy that by empowering labor unions and farmers (which they did), and by raising taxes on corporate profits (they tried and failed). Regulation of the economy was a favorite remedy. Some of those regulations, such as establishing the Securities and Exchange Commission which regulates Wall Street, won widespread support and continue to this day. Most of the other regulations were abolished or scaled back in a bipartisan wave of deregulation 1975-1985.

Public behavior

The British economist John Maynard Keynes coined the term "the paradox of thrift" to describe the deepening of the Great Depression after 1929. The paradox of thrift indicates that when people decide to save more this may end up causing people to spend less. The increased savings (reduced spending) due to the panic following the stock market crash of 1929 left markets saturated, contributing to price deflation, perpetuating the Great Depression. When people decided to save more (spend less) businesses responded by cutting back on production and laying off workers. Businesses, cutting back on investment spending because they were pessimistic about the future as well, were also doing their share of causing a reduction in aggregate expenditures, reducing their investments, setting in motion a dangerous cycle: less investment, fewer jobs, less consumption and even less reason for business to invest. The lower aggregate expenditures in the economy contributed to a multiple decline in income, well below full employment. The economy may reach perfect balance, but at a cost of high unemployment and social misery. At the lower income levels during the Great Depression, savings were much lower than before— hence, the paradox of thrift. As a result, Keynesian economists were increasingly calling for government to take up the slack.

Effects

The Great Depression in Canada

Main article: Great Depression in CanadaCanada is sometimes considered to be the country hardest hit by the Great Depression. The economy fell further than that of any nation other than the United States, and it took far longer to recover. It hit especially hard in Western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939.

The Great Depression in the United Kingdom

Main article: Great Depression in the United KingdomThe World Depression broke at a time when the United Kingdom was still far from having recovered from the effects of the First World War more than a decade earlier.

A major cause of the international financial instability, which preceded and accompanied the Great Depression, was the debt which many European countries had accumulated to pay for their involvement in the war. This debt destabilised many European economies as they tried to rebuild during the 1920s.

Great Britain was driven off the gold standard in 1931.

The Great Depression in France

Main article: Great Depression in FranceThe crisis affected France a bit later than other countries, around 1931. As in the United Kingdom, France was recovering from World War I, trying without much success to recover the reparations from Germany. This led to the occupation of the Ruhr at the beginning of the 1920s, which failure in turn led to the implementation of the Dawes Plan of August 1924 and the Young Plan of 1929. However, the depression had drastic effects on the local economy, and partly explains the February 6, 1934 riots and even more the formation of the Popular Front, led by SFIO socialist leader Léon Blum, which won the elections in 1936.

The Great Depression in Italy and Germany

Mussolini and Hitler followed an autarky economic policy, which, composed with the militarist, xenophobic and nationalistic characteristics of the fascist and nazi ideology, led to World War II. On a purely economic level, the work needed to build the military power necessary for its expansionist goals was a relative success, although it was treading a path of autodestruction.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

The Great Depression in Spain

Main article: Great Depression in SpainSpain had a relatively isolated economy, with high protective tariffs and was experiencing other economic problems with the need for land reform, overall development, and better education levels. It was not one of the main countries affected by the Depression. However, because the country was destroyed by civil war and suffered from isolation because of Francisco Franco's fascist regime, GDP levels of 1939 were not recovered until 1953.

The Great Depression in Australia

Main article: Great Depression in AustraliaAustralia, with its extreme dependence on exports, particularly primary products such as wool and wheat, is thought to have been one of the hardest-hit countries in the Western world along with Canada and Germany. Unemployment reached a record high of 29% in 1932, one of the highest rates in the world. There were also incidents of civil unrest, particularly in Australia's largest city, Sydney.

The Great Depression in East Asia

Main article: Great Depression in East AsiaJapan, with a growing industrial base, was hurt slightly, with GDP falling 8% 1929-30. The economy recovered by 1932.

The Great Depression in Latin America

Main article: Great Depression in Latin AmericaBefore the 1929 crisis, links between the world economy and Latin American economies had been established through American and British investment in Latin America and Latin American exports to the world. As a result, Latin Americans export industries felt the depression quickly. World prices for commodities such as wheat, coffee and copper plunged. Exports from all of Latin America to the US fell in value from $1.2 billion in 1929 to $335 million in 1933, rising to $660 million in 1940.

The Great Depression in South Africa

Main article: Great Depression in South AfricaThe Great Depression had a pronounced economic and political effect on South Africa, as it did to most nations at the time. As world trade slumped, demand for South African agricultural and mineral exports fell drastically. Many historians think that the social discomfort caused by the depression was a contributing factor in the defeat of Barry Hertzog and his National Party in the 1933 general election.

The Great Depression in the United States

Main article: Great Depression in the United StatesThe Great Depression had a significant impact on the economy and people of the United States. President Herbert Hoover was widely blamed, and he was defeated in 1932 by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt launched a New Deal designed to provide emergency relief to upwards of a third of the population, to recover the economy to normal levels, and to reform failed parts of the economic system. Relatively high unemployment lingered until the early 1940s.

Responses

Initial reaction in the United States

US President Herbert Hoover's Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon advised Hoover that a shock treatment would be the best response: "Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. . . . will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people" (Hoover Memoirs 3:9). Hoover rejected the advice, made Mellon an ambassador, and tried to keep wages high, farm prices high, and public works going to ameliorate the distress—but it only got worse.

New Deal in the United States

Main article: New DealFrom 1932 onward Roosevelt argued that a restructuring of the economy—a "reform" would be needed to prevent another depression. New Deal programs sought to stimulate demand and provide work and relief for the impoverished through increased government spending, by:

- Reforming the financial system, especially the banks and Wall Street. In 1933 the Securities Act of 1933 comprehensively regulated the securities industry. This was followed by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 which created the Securities and Exchange Commission. (Though amended, the key provisions of both Acts are still in force as of 2006). Federal insurance of bank deposits was provided by the FDIC (still operating as of 2006), and the Glass-Steagal Act (which remained in effect for 50 years).

- instituting regulations which ended what was called "cut-throat competition" which kept forcing down prices and profits for everyone. (The NRA—which ended in 1935).

- Setting minimum prices and wages and competitive conditions in all industries (NRA)

- encouraging unions that would raise wages, to increase the purchasing power of the working class (NRA)

- cutting farm production so as to raise prices and make it possible to earn a living in farming (done by the AAA and successor farm programs)

The most controversial of the New Deal agencies was NRA which ordered:

- businesses to work with government to set price codes;

- the NRA board to set labor codes and standards;

These reforms (together with relief and recover measures) are called by historians the First New Deal. It was centered around the use of an alphabet soup of agencies set up in 1933 and 1934, along with the use of previous agencies such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, to regulate and stimulate the economy. By 1935 the "Second New Deal" added Social Security, a national relief agency the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and, through the National Labor Relations Board a strong stimulus to the growth of labor unions. Unemployment fell by two-thirds in Roosevelt's first term (from 25% to 9%), but then remained stubbornly high until 1942.

In 1929, federal expenditures constituted only 3% of the GDP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, funded primarily by a growth in the national debt. The debt as proportion of GNP rose under Hoover from 20% to 40%. FDR kept it at 40% until the war began, when it soared to 128%. (See graph below) Conservatives after the Recession of 1937, were able to form a bipartisan Conservative coalition that stopped further expansion of the New Deal (and by 1943, had abolished all of the relief programs).

On the other hand, according to economist Robert Higgs, when looking only at the supply of consumer goods, significant GDP growth only resumed in 1946 (Higgs does not estimate the value to consumers of collective goods like victory in war). (Higgs 1992) To Keynesians, the war economy showed just how large the fiscal stimulus required to end the downturn of the Depression was, and it led, at the time, to fears that as soon as America demobilized, it would return to Depression conditions and industrial output would fall to its pre-war levels. That is, Keynesians predicted a new depression would start after the war—a false prediction.

Keynesian models

In the early 1930s, before John Maynard Keynes wrote The General Theory, he was advocating public works programs and deficits as a way to get the British economy out of the Depression. Although Keynes never mentions fiscal policy in The General Theory, and instead advocates the need to socialize investments, Keynes ushered in more of a theoretical revolution than a policy one. Keynes's basic idea was simple. In order to keep people fully employed, governments have to run deficits when the economy is slowing because the private sector won't invest enough.

As the Depression wore on, Franklin D. Roosevelt tried public works, farm subsidies and other devices to restart the economy, but he never completely gave up trying to balance the budget. According to the Keynesians he had to spend much more money; they were unable to say how much more money. With fiscal policy, however, government could provide the needed Keynesian spending by decreasing taxes, increasing government spending, increasing individuals' incomes. As incomes increased, they would spend more. As they spent more, the multiplier effect would take over and expand the effect on the initial spending. The Keynesians did not estimate what the size of the multiplier was. The Keynesian model, as Roosevelt complained, was all about diagrams. Keynes's visit to the White House in 1934 to urge President Roosevelt to do more deficit spending was a debacle. Roosevelt complained to Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, "He left a whole rigmarole of figures— he must be a mathematician rather than a political economist." That is, Keynes was all theory with no practical advice whatsoever. Neither Keynes nor his followers was ever able to estimate how much additional spending was needed. They were not even able to estimate their own "multiplier." They assumed that poor people would spend new incomes and not pay back debts owed to landlords, grocers and family. Their ideas of the consumption function were disproven in the 1950s (by Milton Friedman and Franco Modigliani.)

American recession of 1937

During the Recession of 1937 the American economy took an unexpected nosedive that continued through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. Unemployment jumped from 14.3% in 1937 to 19.0% in 1938.

The administration reacted by launching a rhetorical campaign against monopoly power, which was cast as the cause of the new dip. The president appointed an aggressive new direction of the antitrust division of the Justice Department, but this effort lost its effectiveness once World War II, a far more pressing concern, began.

But the administration's other response to the 1937 deepening of the Great Depression had more tangible results. Ignoring the pleas of the Treasury Department, Roosevelt embarked on an antidote to the depression, reluctantly abandoning his efforts to balance the budget and launching a $5 billion spending program in the spring of 1938, an effort to increase mass purchasing power. Business-oriented observers explained the recession and recovery in very different terms from the Keynesians. They argued that the New Deal had been very hostile to business expansion in 1935-37, had encouraged massive strikes which had a negative impact on major industries such as automobiles, and had threatened massive anti-trust legal attacks on big corporations. All those threats diminished sharply after 1938. For example, the antitrust efforts fizzled out without major cases. The CIO and AFL unions started battling each other more than corporations, and tax policy became more favorable to long-term growth.

Gold Standard

Britain departed from the gold standard in September 1931, allowing the sterling to float. As a result, the value of the sterling dropped significantly and British exports became cheaper. In 1933, the United States followed suit and dropped the gold standard.

Rearmament and recovery

The massive rearmament policies to counter the threat from Nazi Germany helped stimulate the economies of many countries around the world. By 1937 unemployment in the United Kingdom had fallen to 1.5 million. The mobilisation of manpower following the outbreak of war in 1939 finally ended unemployment.

In the United States, the massive war spending doubled the GNP, helping end the depression. Businessmen ignored the mounting national debt and heavy new taxes, redoubling their efforts for greater output as an expression of patriotism. Patriotism drove most people to voluntarily work overtime and give up leisure activities to make money after so many hard years. Patriotism meant that people accepted rationing and price controls for the first time. Cost-plus pricing in munitions contracts guaranteed that businesses would make a profit no matter how many mediocre workers they employed, no matter how inefficient the techniques they used. The demand was for a vast quantity of war supplies as soon as possible, regardless of cost. Businesses hired every person in sight, even driving sound trucks up and down city streets begging people to apply for jobs. New workers were needed to replace the 12 million working-age men serving in the military. These events magnified the role of the federal government in the national economy. In 1929, federal expenditures accounted for only 3% of GNP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, and Roosevelt's critics charged that he was turning America into a socialist state. However, spending on the New Deal was far smaller than on the war effort.

Political consequences

The crisis had many political consequences, among which the abandonment of classic economic liberal thesis, which Roosevelt replaced in the US by keynesian policies. It was a main factor in the implementation of social-democracy and planned economy in European countries after the war. It wouldn't be until the 1970s and the beginning of monetarism that this keynesian economy was put into doubt, leaving the way to neoliberalism.

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

See also

- Aftermath of World War I

- Business cycle

- Cities in the great depression

- Economic collapse

- New Deal

- Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

Notes

- Willard W. Cochrane. Farm Prices, Myth and Reality 1958. p. 15; League of Nations, World Economic Survey 1932-33 p. 43. .

References

- Ambrosius, G. and W. Hibbard, A Social and Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe (1989)

- Bernanke, Ben S. "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach" Journal of Money, Credit & Banking, Vol. 27, 1995

- Brown, Ian. The Economies of Africa and Asia in the inter-war depression (1989)

- Davis, Joseph S., The World Between the Wars, 1919-39: An Economist's View (1974)

- Feinstein. Charles H. The European economy between the wars (1997)

- Garraty, John A., The Great Depression: An Inquiry into the causes, course, and Consquences of the Worldwide Depression of the Nineteen-Thirties, as Seen by Contemporaries and in Light of History (1986)

- Garraty John A. Unemployment in History. (1978)

- Garside, William R. Capitalism in crisis: international responses to the Great Depression (1993)

- Haberler, Gottfried. The world economy, money, and the great depression 1919-1939 (1976)

- Hall Thomas E. and J. David Ferguson. The Great Depression: An International Disaster of Perverse Economic Policies (1998)

- Kaiser, David E. Economic diplomacy and the origins of the Second World War: Germany, Britain, France and Eastern Europe, 1930-1939 (1980)

- Kindleberger, Charles P. The World in Depression, 1929-1939 (1983)

- League of Nations, World Economic Survey 1932-33 (1934)

- Madsen, Jakob B. "Trade Barriers and the Collapse of World Trade during the Great Depression"' Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 67, 200

- Mundell, R. A. "A Reconsideration of the Twentieth Century' "The American Economic Review" Vol. 90, No. 3 (Jun., 2000), pp. 327-340

- Rothermund, Dietmar. The Global Impact of the Great Depression (1996)

- Tipton, F. and R. Aldrich, An Economic and Social History of Europe, 1890–1939 (1987)

- For US specific references, please see complete listing in the Great Depression in the United States article.

External links

- Depression video clip (1 min, 33 sec).

- An Overview of the Great Depression from EH.NET by Randall Parker.

- Great Myths of the Great Depression by Lawrence Reed

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Library & Museum for copyright-free photos of the period