| Revision as of 01:13, 2 June 2006 edit61.2.21.173 (talk) →Battles← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:58, 2 June 2006 edit undoGraham87 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Importers291,457 editsm →Battles: replace link to blog with wikilinkNext edit → | ||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

| *], ] | *], ] | ||

| *], capture of ] by ] | *], capture of ] by ] | ||

| *], ] | *], ] | ||

| *], ] | *], ] | ||

| *], ] | *], ] | ||

Revision as of 09:58, 2 June 2006

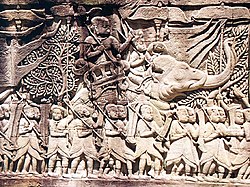

War elephants were important, although not widespread, weapons in ancient military history. Their main use was in charges, to trample the enemy and/or break their ranks. War elephants were exclusively male animals, because they were faster, more aggressive, and the females had a tendency to run away from other females.

History

Elephant taming (not full domestication, they were still captured in the wild) began in the Indus Valley civilization around 4,000 years ago. The first species to be tamed was thus the Asian elephant, for agricultural ends. The first military application of elephants dates from around 1100 BC in North India and Pakistan, which is mentioned in several Vedic Sanskrit hymns from this era.

From India, war elephants were taken to the Persian Empire where they were used in several campaigns. The battle of Gaugamela (October 1, 331 BC), fought against Alexander the Great was probably among the first confrontations of Europeans with war elephants. The fifteen animals, placed at the centre of the Persian line, made such an impression on the Macedonian troops that Alexander felt the need to sacrifice to the god of fear in the night before the battle. Gaugamela was Alexander's greatest success, but the enemy elephants made enough of an impact on him that following his conquest of Persia, Alexander recognised the use of the animals and incorporated a number of them into his own army. Five years later, in the battle of the Hydaspes River against Porus, although without his own, Alexander already knew how to deal with elephants. Porus, who ruled in Punjab, Pakistan, employed 200 war elephants in this battle, which presented a challenge to Alexander, though he defeated Porus. At this time, the Magadha Empire further east in northern India and Bengal, had 6000 war elephants, while Chandragupta Maurya a short time later had 9000 war elephants. These numbers of war elephants were many times larger than the numbers employed by the Persians and Greeks.

The successful military use of elephants spread across the world. The successors to Alexander's empire, the Diadochi, used hundreds of Indian elephants in their wars. The Egyptians and the Carthaginians began taming African elephants for the same purpose, as did the Numidians and the Kushites. The animal used was the Forest elephant, specifically, the North African relict population which eventually became extinct from overexploitation. This particular breed was smaller than the Asian elephants used by the Seleucids, and were quite often too scared to engage them in combat. The African savannah elephant, larger than the African forest elephant or the Asian elephant, proved difficult to tame for war purposes and was not used as extensively. Elephants used by the Egyptians at the battle of Raphia in 217 BC were smaller than their Asian counterparts, but that did not guarantee victory for Antiochus III the Great of Syria.

Sri Lankan history records elephants were used as mounts for kings leading their men in the battle field. The elephant "Kandula" was King Dutugamunu's mount (200 BC) and "Maha Pabbata" the mount of King Elahara during their historic encounter in the battlefield.

Pliny the Elder (45 AD) one of the great Roman historians, in Book 6 of his 37 volume history, states that Megastenes had recorded the opinion of one Onesicritus that the Sri Lankan elephants are larger, fiercer and better for war than others. For this reason and the proximity of elephants close to sea ports inter alia made Sri Lanka's elephants a lucrative trading commodity. Even in peacetime, death by elephant was reserved for traitors and other offenders against the state and royalty.

In the next centuries, further use of war elephants in Europe was mainly against the Roman Republic. From the battle of Heraclea (280 BC in the Pyrrhic War) to the famous march across the Alps by Hannibal during the Second Punic war, elephants terrified the Roman legions. Like Alexander, the Romans found a way to cope with the dangerous elephant charges. In Hannibal's last battle (Zama, 202 BC), his elephant charge was ineffective because the Roman maniples simply made way for them to pass. More than a century later, in the battle of Thapsus (February 6 46 BC), Julius Caesar armed his fifth legion (Alaudae) with axes and commanded his legionaries to strike at the elephant's legs. The legion withstood the charge and the elephant became its symbol. Thapsus was the last significant use of elephants in the West.

A reportedly effective anti-elephant weapon was the pig. Pliny the Elder reported that "elephants are scared by the smallest squeal of a pig" (VIII, 1.27). A siege of Megara was reportedly broken when the Megarians poured oil on a herd of pigs, set them alight, and drove them towards the enemy's massed war elephants. The elephants bolted in terror from the flaming squealing pigs.

The Parthian dynasty of Persia occasionally used war elephants in their battles against Roman empire, but they were of substantial importance in the army of the subsequent Sassanid dynasty. The Sassanids used these giant beasts in many of their campaigns against their western enemies. One of the most memorable ones was Battle of Vartanantz in which Sassanid elephants caused much fear and crushed Armenian rebels. Another example is the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah in which elephants were used in numbers in the Sassanid army.

In the Middle Ages, elephants were seldom used. Charlemagne took his elephant, Abul-Abbas, when he went to fight the Danes in 804, and the Crusades gave Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor the opportunity to capture an elephant in the Holy Land, later used in the capture of Cremona in 1214.

It was the use of elephants, again by an Indian Sultanate, that almost put an end to Timur's conquests. In 1398 Timur's army faced more than one hundred Indian elephants in battle and almost lost by pure fear of his troops. Historical accounts say that the Turks won due to an ingenious strategy: Timur set flaming straw on the back of his camels before the charge. The smoke made the camels run forward and scared the elephants, who crushed their own troops in an attempt to retreat. Another account of the campaign (that of Ahmed ibn Arabshah) reports that Timur used oversized caltrops to halt the elephant charge. Later, the Turkish leader used the animals against the Ottoman Empire.

It is recorded that King Rajasinghe the First, when he laid siege to the Portuguese fort at Colombo, Sri Lanka in 1558, had an elephant phalanx of 2,200 (Peris 1913). The officer-in-charge of the Royal stables was called the "Gaja Nayake Nilame". His off-sider was the "Kuruve Lekham" who controlled the Kuruwe or elephant men. The training of war elephants was the duty of the Kuruwe clan who came under their own Muhandiram.

With the advent of gunpowder warfare in the late 15th century, war elephants became obsolete for charging because they could be easily knocked down by a cannon shot.

Tactical use

There were plenty of military purposes for which elephants could be used. As enormous animals, they could carry heavy cargoes and provided a useful means of transport. In battle, war elephants were usually deployed in the centre of the line, where they could be useful to prevent a charge or start one of their own.

An elephant charge can reach about 30 km/h (20 mi/h), and unlike horse cavalry, could not be easily stopped by an infantry line setting spears. Its power was based on pure force: crashing into an enemy line, trampling and swinging its tusks. Those men who were not crushed were at least knocked aside or forced back. Moreover, the terror elephants could inspire against an enemy not used to fighting them (even the very disciplined Romans) could cause them to break and run just on the charge's momentum alone. Horse cavalry were not safe either, because horses unaccustomed to the smell of elephants panic easily. The elephants' thick hide made them extremely difficult to kill or neutralize in any way, and their sheer height and mass offered considerable protection for their riders.

However, they also had a tendency to panic themselves: after sustaining moderate wounds or when their driver was killed, they would run amok, indiscriminately causing casualties as they sought escape. Their panicked retreat could inflict heavy losses on either side. Experienced Roman infantry often tried to sever their trunks, causing an instant panic, and hopefully causing the elephant to flee back into its own lines. Fast skirmishers armed with javelins were also used to drive them away, as javelins and similar weapons could madden an elephant. The cavalry sport of tent pegging grew out of training regimens for horse mounted cavaliers to incapacitate or turn back war elephants.

Sri Lankan history records that heavy iron chains with steel balls at the end were tied to the trunks of elephants which they were trained to swirl and whirl menacingly with great agility. This was a very efficient way to keep advancing troops at bay. A few elephants charging with swirling iron balls at the end of a chain and the consternation it can cause in the ranks of the enemy is better imagined than described.

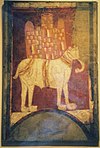

In the Punic wars, a war elephant was heavily armoured and carried on his back a tower, called a howdah, with a crew of three men: archers and/or men armed with sarissas (a six metre long pike). Forest war elephants, much smaller than their African or Asian relatives, were not strong enough to support a tower and carried only two or three men. There was also the driver, called a mahout and usually Numidian, who was responsible for controlling the animal. The mahout also carried a chisel-blade and a hammer to cut through the spinal cord and kill the animal if the elephant went berserk. Elephants have been compared to Second World War tanks, but their tactical uses differ too much for the comparison to hold.

Jayantha Jayawardhene in his "Elephant in Sri Lanka" (1994) gives the view that elephants were unreliable in battle except to intimidate the enemy. He says, "they have been found to be skittish and easily alarmed by unfamiliar sounds and for this reason they were found prone to break ranks and flee."

Battles

Some notable battles involving war elephants include:

- 331 BC, Battle of Gaugamela

- 326 BC, Battle of the Hydaspes River

- 317 BC, Battle of Paraitacene

- 316 BC, Battle of Gabiene

- 312 BC, Battle of Gaza

- 301 BC, Battle of Ipsus

- 280 BC, Battle of Heraclea

- 279 BC, Battle of Asculum

- 275 BC, Battle of Beneventum

- 262 BC, Siege of Agrigentum

- 255 BC, Battle of Tunis

- 252 BC, Siege of Panoramus

- 238 BC, Battle of Utica

- 238 BC, Battle of "The Saw"

- 239 BC, Battle of the Bagradas River

- 219 BC-218 BC, Siege of Saguntum

- 218 BC, Crossing of the Alps and the Battle of Trebia

- 217 BC, Battle of Raphia

- 202 BC, Battle of Zama

- 190 BC, Battle of Magnesia

- 164 BC, Battle of Beth-zur

- 153 BC, Roman siege of Numantia (Spain)

- 149 BC-146 BC, Siege of Carthage

- 108 BC, Battle of Muthul

- 46 BC, Battle of Thapsus

- 451, Battle of Vartanantz

- 636, Battle of al-Qādisiyyah

- 1214, capture of Cremona by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

- 1659, Battle of Khajwa

- 1556, Second battle of Panipat

- 1761, Third battle of Panipat

War elephants in popular culture

- Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book contains two stories in which war elephants appear, "Toomai of the Elephants" and "Her Majesty's Servants".

- J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional war-beasts, the Mûmakil or Oliphaunt, are modelled after war elephants.

- Age of Empires, a real-time strategy computer game, features war elephants as a mêlée unit or a ranged unit ("elephant archers").

- Age of Empires II, the sequel of Age of Empires, include war elephants (mêlée unit), but only in the Persian civilization.

- Rome: Total War is a computer game that also features elephants as a mêlée or a ranged unit.

- Civilization II includes war elephants as a unit any civilization can build. They are slightly stronger than early horsemen and slightly weaker than knights, which they upgrade to.

- Civilization III is a computer game that includes war elephants as the unique unit of India.

- Civilization IV includes war elephants as a unit which can be built by any civilization with ivory. They are especially effective against mounted units.

- Age of Mythology features war elephants available to the Egyptian civilizations. They are a strong but slow cavalry unit effective against all units, with the exception of infantry and myth units.

- Rise of Nations: Thrones and Patriots, a real-time strategy computer game, features war elephants as a mêlée unit or a ranged unit for Persia and India.

- War elephants are mentioned in and feature prominently in a key scene of Oliver Stone's 2004 film Alexander.

See also

- Tent pegging

- Crushing by elephant

- Sassanid army

- History of elephants in Europe

- List of historical elephants

- Military animals

- Chinese chess - which includes the war elephant (象 xiàng) as one of the pieces; the chess bishop was also originally an elephant.

References

- Alexander the Great, by Robin Lane Fox, Penguin (2004) ISBN 0141020768

- History of Warfare, by John Keegan, Pimlico (1993) ISBN 0679730826

- The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265-146BC, by Adrian Goldsworthy, Orion (2003) ISBN 0304366420

External links

Listen to this article(2 parts, 10 minutes)

Categories: