| Revision as of 09:22, 6 June 2014 editArjayay (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers628,332 editsm Sp - Referrence > Reference← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:59, 8 June 2014 edit undoZoupan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users66,156 edits reverting. common historical knowledge of the term "Vlachs", as presented, should not be removed. present your edits at the talk page.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| '''Morlachs''' (] and {{lang-sr|Morlaci}}, {{lang-sr-cyr|Морлаци}}) was the name used for the rural population in the ] in the 16th and 17th centuries, which was primarily composed of Eastern Orthodox Serbs, and to a lesser degree Roman Catholic Croats. There were several notable warriors of this group that served the ], including ] and ]. | |||

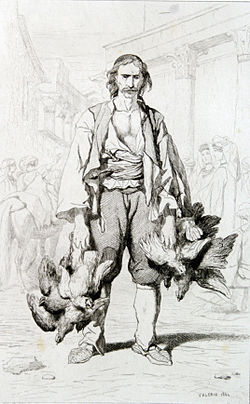

| ⚫ | ] region. Théodore Valerio (1819–1879), 1864.]] | ||

| '''Morlachs''' (] and {{lang-sr|Morlaci}}, {{lang-sr-cyr|Морлаци}}) was an ] or ] used for the rural population in the ] and ] hinterlands (western Balkans in modern use) in the 14th and 18th centuries, usually connected with ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| ''Morlachs'' is derived from the Italic (Latin) term "Morlacchi". According to some, the etymology is cognate to "Black Vlachs" (from Greek ''mauro'', black). Alberto Fortis theorized that it was derived from Slavic words ''more'' (sea) and ''laci'' (strong) ("strongmen by the sea"). | |||

| Ethnonym ''Morlach'', is derived from the Italian term "Morlacoo", Latin term "Morlachus" (Murlachus), being cognate from Greek {{lang|el|Μαυροβλάχοι}} (Mauroblakhoi), meaning "Black Vlachs" (from Greek ''mauro'', dark or black). The ] term in singular is ''{{lang|hr|Morlak}}'' and plural ''{{lang|hr|Morlaci}}'' or {{lang|sr-Cyrl|Морлаци}}. In Latin sources there are references to them also as "Nigri Latini".<ref>{{cite book| url=http://www.muzic-ivan.info/hrvatska_kronika.pdf| title=Hrvatska kronika u Ljetopisu pop Dukljanina| author=Ivan Mužić| publisher=Muzej hrvatski arheoloških spomenika| location=Split| year=2011| page=66 (''Crni Latini''), 260 (''qui illo tempore Romani vocabantur, modo vero Moroulachi, hoc est Nigri Latini vocantur.'')| quote=In some Croatian and Latin redactions of the ], from 16th century.}}</ref> ] derived it from lat. ''maurus'' - gr. ''maurós'' (dark), which diphthongs ''au'' and ''av'' indicate to Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant.<ref>{{cite book| author=P. Skok| title=Etymological dictionary of Croatian or Serbian language| publisher=]| location=Zagreb| volume=II| year=1972| page=392-393}}</ref> | |||

| The historical term "Vlach" was used for anyone who professed the Orthodox faith as opposed to Catholicism. ''Vlachs'', referring to pastoralists, was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire, Venetian Republic, Habsburg lands, etc.{{Cref2|a}} | |||

| There are several interpretations of the ethnonym and phrase "moro/mavro/mauro vlasi". The direct translation of the name Morovlasi in Serbo-Croatian would mean Black Vlachs. It is considered that Black was referred to their clothes of brown cloth; The 17th century historian from Dalmatia ], gave the thesis it actually meant "Black Latins" compared to "White Romans" in coastal areas; The 18th century writer ] in his book ''Travels in Dalmatia'' (1774), where extensively wrote about Morlachs, thought it came from Slavic language word "more" (sea), and ''morski Vlasi'' meaning "Sea Vlachs"; The same century writer ] observing Fortis work thought it comes from "more" (sea) and "(v)lac(s)i" (strong) ("strongmen by the sea"),<ref>{{cite book| author=P. S. Nasturel| title=Les Valaques balcaniques aux Xe-XIIIe siècles (Mouvements de population et colonisation dans la Romanie grecque et latine)| publisher=| location=Amsterdam| volume=Byzantinische Forschungen VII| year=1979| page=97}}</ref> and mentioned how the Greeks called Upper Vlachia ''Maurovlachia'' thus Morlachs brought the name with them;<ref>{{cite book| title=Tko su Maurovlasi odnosno Nigri Latini u "Ljetopisu popa Dukljanina"| author=Zef Mirdita| publisher=Croatica Christiana periodica| location=Zagreb| volume=47| year=2001| page=17-27}}</ref> There are also interpretations as "Northern Latins" (Cicerone Poghirc), deriving from the Turkish (Old-Indo European) practice of indicating cardinal directions by colors;<ref>{{cite book| title=Romanisation linguis tique et culturelle dans les Balkans. Survivance et évolution, u: Les Aroumains...| author=Cicerone Poghirc| publisher=]| location=Paris| volume=| year=1989| page=23}}</ref> As reference to their camps and pastures which were built in "dark" places;<ref name=rom>{{cite web| url=http://ilbenandante.altervista.org/testi/vlasi.htm| title=''I Vlasi o Morlacchi, i latini delle alpi dinariche''| accessdate=2. 09. 2012| language=Italian| publisher=ilbenandante}}</ref> It comes from ] peninsula;<ref>{{cite book| title=Prinosi za hrvatski pravno-povjestni rječnik| author=Vladimir Mažuranić| publisher=JAZU| location=Zagreb| year=1908-1922| page=682}}</ref> from ] river;<ref name=rom/> or from African ].<ref>{{cite book| author=Dominik Mandić| title=Postanak Vlaha prema novim poviestnim istraživanjima| publisher=Hrvatska misao| location=Buenos Aires| volume=18-19| year=1956| page=35}}</ref> | |||

| ==Origin and culture== | ==Origin and culture== | ||

| ] | |||

| The origin of group of people called Morlachs, because of the etymology, are beleived originally to have been ], but as stated in work ''Travels in Dalmatia'' from 18th century by Fortis, they were speaking Slavic language, and because of migrations, people came from various parts of the Balkan, and the name passed to other communities. Those people were both of the ] and ] faith. | |||

| The population of the Dinaric highlands, which in the 18th century served as frontiersmen and mercenaries, are generally believed to have migrated from the "]n lands", amid and after the ]'s conquering of those lands.{{cn|date=November 2013}} | |||

| Fortis spotted the physical difference between Morlachs; those from around ], ] and ] generally were blond haired, with blue eyes, and broad face, while those around ] and ] generally brown haired and with narrow face. They also differed in nature. Although by the urban strangers were often seen as "those people" from periphery,<ref name="Wolff">{{Cite book| pages=126, 348| first=Larry| last=Wolff| publisher=Stanford University Press| year=2003| isbn=0-8047-3946-3| title=Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment|}} (With a specific reference to H.G. Wells' Morlocks, p. 348)</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| contribution=Morlachia| first=Richard| last=Brookes| publisher=F.C. and J. Rivington| year=1812| title=The general gazetteer or compendious geographical dictionary| page=501}}</ref> ] called them "barbarians" and "a race of ferocious men, unreasonable, without humanity, capable of any misdeed",<ref name="Wolff"/> while Fortis praised their "noble savagery", moral, family, and friendship virtues, but also complaint their persistent keeping to the old tradition. He found that they sang melancholic verses of epic poetry related to the Turkish occupation, accompanied with the traditional single stringed instrument called ]. They made their living as ] and merchants, as well soldiers. | |||

| Italian Alberto Fortis mentioned the Morlachs in his 1774 work "Put po Dalmaciji";<ref name=Fine-360>Fine 2006, pp. 360-361</ref> he found that they sang beautiful verses of ] related to the Turkish occupation of Serbian ] (Kosovo cycle).<ref name=imagology>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=5Qh-HUwbtpwC&pg=PA235|page=235|title=Imagology|isbn=9042023171}}</ref> They sang the verses along with the traditional single stringed instrument called '']''.<ref name=imagology/> The poetry was collected by the Scottish man-of-letters ], who was close to ].<ref name=imagology/> Contemporary I. Lovrić, said that the Morlachs were Slavs who spoke better Slavic than the Ragusians (owing to the growing Italianization of the Dalmatian coast).<ref name=Fine-360/> Lovrić made no distinction between the Vlachs/Morlachs and the Dalmatians and Montenegrins that were also mentioned (peoples of Croatia and Slavonia were not mentioned), and was not at all bothered by the fact that the Morlachs were predominantly Orthodox Christian.<ref name=Fine-360/> | |||

| ] (1886-1945), after analysing Venetian papers, concluded that they always mentioned the script and language of the Morlachs as "Servian".<ref>Fine 2006</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ⚫ | ].]] | ||

| ===Early history=== | ===Early history=== | ||

| The term '' |

The term ''Morlachi'' is first mentioned in 1352, in the agreement in which Zadar sold salt to the ], in which Zadar retained part of the salt that ''Morlachi'' and others exported by land.<ref>{{cite book|title=Listine o odnošajih Južnoga Slavenstva i Mletačke Republike|publisher=JAZU|location=Zagreb|volume=III|year=1872|page=237|quote=Prvi se put spominje ime »Morlak« (Morlachi) 1352 godine, 24. lipnja, u pogodbi po kojoj zadarsko vijeće prodaje sol Veneciji, gdje Zadar zadržava dio soli koju Morlaci i drugi izvoze, kopnenim putem.}}</ref> The Morlachs would thus have extended from the Serbian interior, perhaps from ], towards the Croatian border, in the 14th century.<ref>{{cite book|title=THE ENCYCLOPEDAEDIA BRITANNICA|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=nfiUjMHSi8YC|year=1929|page=230}}</ref> In August 1417, Venetian authorities were concerned with the "Morlachs and other Slavs" from the hinterland, that were a threat to security in ].<ref>Fine 2006, p. 115</ref> | ||

| In the old Croatian documents, Morlachs were equaled to Vlach shepherds. There were two ''groups'' of Vlachs in documents in Croatia. One group was the regular Vlachs who lived in ], while the others were actual Morlachs, called so in Venice and Italian documents, who lived between ] and ].{{sfn|Mužić|2010|p=21}} Those Vlachs by the end of 14th and 15th century lost, if spoke, their Romanian language, or were at least bilingual.{{sfn|Mužić|2010|p=73|ps=: "As evidence Vlachs spoke a variation of Romanian language, Mužić later in the paragraph referred to the ], and ] on island Krk."}}{{refn|group="nb"|The linguistic assimilation didn't entirely erased Romanian words, the evidence are toponims, and anthroponyms (personal names) with specific Romanian or Slavic words roots, and surname ending suffixes "-ul", "-ol", "-at", "-ar", "-as", "-an", "-et", "-ez", after Slavicization often accompanied with ending suffixes "-ić", "-vić", "-ović".<ref>{{cite book| author=P. Šimunović| title=Uvod U Hrvatsko Imenoslovlje| publisher=Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga| location=Zagreb| year=2009| page=53, 123, 147, 150, 170, 216, 217| language=Croatian}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.rodoslovlje.hr/istaknuta-vijest/vlasi-u-nama-svima| title=Vlasi u nama svima| author=Božidar Ručević| date=2011-02-27| publisher=Rodoslovlje| language=Croatian}}</ref>}} As they adopted Slavic language, the only charateristic "Vlach" element was pastoral way of life.{{sfn|Mužić|2010|p=80}}{{refn|group="nb"|That the pastoral way of life was specific for Vlachs is seen in the third chapter of eight book in '']'', 12th century work by ], where along Bulgars are mentioned tribes who live a nomadic life usually called ''Vlachs''.<ref name="Zef">{{cite book| author=Zef Mirdita| title=Balkanski Vlasi u svijetlu podataka Bizantskih autora| publisher=Croatian History Institute| location=Zagreb| year=1995| page=65, 66| language=Croatian}}</ref> In this and many other older Medieval documents, the term was often mentioned along other ethnic names, thus being more an ethnic than just a social-professional category.<ref name="Zef"/> Although the term included both of them, P. S. Nasturel emphasized there existed other general expressions for pastors.<ref name="Zef"/>}} Some groups continued to speak Romanian language, as seen by their descendents on the island of Krk and villages around the Čepić lake in Istria.{{sfn|Mužić|2010|p=73}} | |||

| In the 15th century, those groups of Vlachs, possibly of Morlachs, were invited to settle into the ] (throughout, and mountain ]) after the various devastating outbreaks of the plague and war between 1400–1600, and reached the island of ]. | |||

| ===16th century=== | ===16th century=== | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| As many former inhabitants of the Austrian-Ottoman borderland fled northwards or were captured by the Ottoman invaders, they left unpopulated areas. The ] encouraged people, mostly Orthodox Serbs from the ], to settle as free peasant soldiers, establishing the ]s (''Militärgrenze'') in 1522 (hence they were known as ], ''krajišnici''). The militarized frontier would serve as a buffer against Ottoman incursions. The Military frontiers had territory of modern Croatia, Serbia, Romania and Hungary. The colonists were granted small tracts of land, exempted from some obligations, and were to retain a share of all war booty. The Grenzers elected their own captains (vojvode) and magistrates (knezovi). All Orthodox settlers were promised freedom of worship. By 1538, the ] and ] were established. Serbs acted as the '']'' against Ottoman incursions.<ref>William Safran, The secular and the sacred: nation, religion, and politics, p. 169</ref> The Military frontiers are virtually identical to the present Serb settlements in Croatia (war-time ]).<ref>Nicholas J. Miller, 1998, Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War, p. 10</ref> | |||

| From this century, the previous association of the term with autochthonous people starts to lose. In most documents by Venice, Morlachs are usually called immigrants (initially of both Catholic and Orthodox faith) from conquested territory previously of Croatian and Bosnian kingdoms by Ottoman Empire, who settled in inland of the coastal cities, enterted the military service, and before the half of 17th century lived on Venice-Ottoman border.<ref name="Enc">{{cite web| title=Morlaci| url=http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=41968| author=Croatian Encyclopaedia| year=2011| language=Croatian}}</ref> | |||

| In 1579, several groups of ''Morlachs'', understood as Serb tribes in Dalmatia, migrated to the Austrian ] and requested to be employed as military colonists. Initially, there were some tensions between these and the established ].<ref name="Rothenberg1960">{{cite book|author=Gunther Erich Rothenberg|title=The Austrian military border in Croatia, 1522-1747|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=g701AAAAIAAJ|year=1960|publisher=University of Illinois Press|page=50}}</ref> In 1593, ''provveditore generale'' ] mentioned three nations constituting the Uskoks, the "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".<ref>Fine 2006, p. 218</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| The name "Morlach" expanded also to geographical terms, the mountain ] was called ''Montagne della Morlacca'' (Morlach Mountain), lands below ''Morlachia'', and Velebits canal the ''Canale della Morlacca''.<ref name="Enc"/> | |||

| ===17th century=== | ===17th century=== | ||

| In the 17th-century, ] was one of the Morlach leaders in Dalmatia. In the summer of 1685, Cosmi, the Archbishop of Split, wrote that Stojan had brought 300 families with him to Dalmatia, and also that around Trogir and Split there were 5000 refugees from Turkish lands, without food - seen as a serious threat to the defense of Dalmatia.<ref name=Ninic80>{{cite book|author=Ivan Ninić|title=Migrations in Balkan history|page=80}}</ref> ] sent by the ] proved insufficient, and the Serbs were forced to launch expeditions into Turkish territory.<ref name=Ninic80/> | |||

| In the 17th-century, at the time of ] and ] was settled the biggest number of Morlachs, mostly inland of cities and ] of Zadar.<ref name="Enc"/> They were skilled in warfare and familiar with local territory, and served as paid soldiers in both Venice and Ottoman armies. Their activity was simultaneous with those of ]. Military service granted them lands, freed from usual trials, and gave them rights which freed from full debt (only 1/10 yield) law, thus many joined the "Morlachs" or "Vlachs" armies.<ref name="Tusculum 2">{{cite book| url=http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=78147| title=Izvori za prva desetljeća novoga Vranjica i Solina| author=Milan Ivanišević| location=Solin| publisher=Tusculum| page=98| volume=2, No. 1 September| year=2009| language=Croatian}}</ref> At the time, some notable head leaders of Morlachs,{{refn|group="nb"|The head leaders in Venice, Ottoman and local Slavic documents were titled as ''capo'', ''capo direttore'', ''capo principale de Morlachi'' (J. Mitrović), ''governatnor delli Morlachi'' (S. Sorić), ''governator principale'' (I. Smiljanić), ''gospodin serdar s vojvodami'' or ''lo dichiariamo serdar;'' ], and ].<ref name="Desnica">{{cite book| url=http://www.historiografija.hr/hz/1952/HZ_5_12_SUCEVIC.pdf| title=Istorija Kotarski Uskoka 1646-1749| author=Boško Desnica| location=Venice| publisher=]| volume=I-II| page=140, 141, 142| year=1950-1951| language=Serbian}}</ref>}} who were also sung in epic poetry, are ], Ilija and ], Ilija, Franjo and Petar Smiljanić, Stjepan and Marko Sorić, ], Šimun Bortulačić, Božo Milković, ], ], and counts Franjo and Juraj Posedarski.<ref name="Enc"/><ref>{{cite book| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=1dovAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1&dq=sign+lovric&hl=it&ei=DyRtTPCdKtPK4gbnrqiSCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false| title=Osservazioni sopra diversi pezzi del Viaggio in Dalmazia del signor abate Alberto Fortis coll'aggiunta della Vita di Soçivizça| author=Ivan Lovrić| location=Venice| page=223| language=Italian}}</ref><ref name="Drago">{{cite book| url=http://www.ffzg.unizg.hr/pov/zavod/triplex2/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/ROKSANDIC,%20Triplex%20confinium.pdf| title=Triplex Confinium, Ili O Granicama I Regijama Hrvatske Povijesti 1500-1800| author=Drago Roksandić| location=Zagreb| publisher=Barbat| page=140, 141, 169| year=2003| language=Croatian}}</ref><ref name="Desnica"/> As Morlachs were of both Ortodox and Catholic faith, roughly, Mitrović-Janković family were the leaders of Ortodox, while Smiljanić family of Catholic Morlachs.<ref name="Desnica"/> | |||

| ===18th—19th century=== | |||

| After the dissolution of Republic of Venice in 1797, and loss of power in Dalmatia, the term Morlach would steadly dissappear from use.<ref name="Enc"/> Although in some historical documents were referred as a nation, it can't be told it was, or that the name belonged to only one ethnic group, ie. Vlachs who didn't manage to make a national identity, or later ] or ], yet according to the religious affiliation, they assimilated to these two ethnic groups.<ref name="Enc"/> | |||

| In the 1851 census of Dalmatia, the Morlachs, citizens of Ragusa and inhabitants of Dalmatian coast and islands declared themselves ].<ref name="Dakić1994">{{cite book|author=Mile Dakić|title=The Serbian Krayina: Historical Roots and Its Birth|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EBq5AAAAIAAJ|year=1994|publisher=Iskra|page=12}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | ] region. Théodore Valerio (1819–1879), 1864.]] | ||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| According to the 1991 Croatian census, 22 people declared themselves as Morlachs.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} There was no data on Morlachs in the 2001 Croatian census.<ref></ref> | The population that Venetians called Morlachs were absorbed in the Serbian and Croatian nationalities by the 19th century. According to the 1991 Croatian census, 22 people declared themselves as Morlachs.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} There was no data on Morlachs in the 2001 Croatian census.<ref></ref> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Annotations== | ==Annotations== | ||

| {{Cnote2 Begin|liststyle=upper-alpha}} | |||

| {{Reflist|group="nb"}} | |||

| ⚫ | {{Cnote2|a| "]", referring to pastoralists, was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire and later.<ref name=LING>{{cite document|url=http://facta.junis.ni.ac.rs/pas/pas2003/pas2003-02.pdf|year=2003}}</ref> Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name 'Vlach' didn't only refer to genuine ] or ] but also to cattle breeders in general.<ref name="LING"/> A letter of Emperor Ferdinand, sent on November 6, 1538, to Croatian ban Petar Keglević, in which he wrote ''"Captains and dukes of the Rasians, or the Serbs, or the Vlachs, who usually call themselves the Serbs"''.<ref name=LING/> Serbs that took refuge in the Habsburg Krajina, were called "Vlachs" by Croats.<ref name=LING/> In the work "About the Vlachs" from 1806, Metropolitan Stevan Stratimirović states that Roman Catholics from Croatia and Slavonia scornfully used the name 'Vlach' for ''"the Slovenians (Slavs) and Serbs, who are of our, Eastern confession (Orthodoxy)"'', and that ''"the Turks in Bosnia and Serbia also call every Bosnian or Serbian Christian a Vlach"'' (T. Đorđević, 1984:110). That the name 'Vlach' was used to signify the Serbs is testified by ] as well.<ref name=LING/> }} | ||

| {{Cnote2 End}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 51: | Line 49: | ||

| ===Sources=== | ===Sources=== | ||

| * {{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans|url=http://books.google.com/?id=wEF5oN5erE0C|isbn=0472025600|date=2006}} | * {{cite book|author=John Van Antwerp Fine|title=When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans|url=http://books.google.com/?id=wEF5oN5erE0C|isbn=0472025600|date=2006}} | ||

| *{{cite book|author1=Norman M. Naimark|author2=Holly Case|title=Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u5tUbUyXtToC&pg=PA38|year=2003|publisher=Stanford University Press|isbn=978-0-8047-4594-9}} | *{{cite book|author1=Norman M. Naimark|author2=Holly Case|title=Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u5tUbUyXtToC&pg=PA38|year=2003|publisher=Stanford University Press|isbn=978-0-8047-4594-9|pages=38–}} | ||

| * {{Cite book|last1=Suppan|first1=Arnold|last2=Graf|first2=Maximilian|title=From the Austrian Empire to the Communist East Central Europe|year=2010|publisher=Lit Verlag|isbn=978-3-643-50235-3}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Mužić|first=Ivan|url=http://www.muzic-ivan.info/vlasi_u_starijoj_hrvatskoj_historiografiji.pdf|title=Vlasi u starijoj hrvatskoj historiografiji|year=2010|publisher=Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika|language=Croatian|location=]|isbn=978-953-6803-25-5}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{commonscat|Morlachs}} | {{commonscat|Morlachs}} | ||

| * {{cite web|title= |

* {{cite web|title=Dalmatia|url=http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Dalmatia|author=Encyclopaedia Britannica|year=1911}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

Revision as of 03:59, 8 June 2014

Morlachs (Croatian and Template:Lang-sr, Serbian Cyrillic: Морлаци) was the name used for the rural population in the Dalmatian hinterlands in the 16th and 17th centuries, which was primarily composed of Eastern Orthodox Serbs, and to a lesser degree Roman Catholic Croats. There were several notable warriors of this group that served the Republic of Venice, including Stojan Janković and Vuk Mandušić.

Etymology

Morlachs is derived from the Italic (Latin) term "Morlacchi". According to some, the etymology is cognate to "Black Vlachs" (from Greek mauro, black). Alberto Fortis theorized that it was derived from Slavic words more (sea) and laci (strong) ("strongmen by the sea").

The historical term "Vlach" was used for anyone who professed the Orthodox faith as opposed to Catholicism. Vlachs, referring to pastoralists, was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire, Venetian Republic, Habsburg lands, etc.

Origin and culture

The population of the Dinaric highlands, which in the 18th century served as frontiersmen and mercenaries, are generally believed to have migrated from the "Serbian lands", amid and after the Ottoman Empire's conquering of those lands.

Italian Alberto Fortis mentioned the Morlachs in his 1774 work "Put po Dalmaciji"; he found that they sang beautiful verses of Serb epic poetry related to the Turkish occupation of Serbian Kosovo (Kosovo cycle). They sang the verses along with the traditional single stringed instrument called gusle. The poetry was collected by the Scottish man-of-letters Lord Bute, who was close to King George III. Contemporary I. Lovrić, said that the Morlachs were Slavs who spoke better Slavic than the Ragusians (owing to the growing Italianization of the Dalmatian coast). Lovrić made no distinction between the Vlachs/Morlachs and the Dalmatians and Montenegrins that were also mentioned (peoples of Croatia and Slavonia were not mentioned), and was not at all bothered by the fact that the Morlachs were predominantly Orthodox Christian.

Boško Desnica (1886-1945), after analysing Venetian papers, concluded that they always mentioned the script and language of the Morlachs as "Servian".

History

Early history

The term Morlachi is first mentioned in 1352, in the agreement in which Zadar sold salt to the Republic of Venice, in which Zadar retained part of the salt that Morlachi and others exported by land. The Morlachs would thus have extended from the Serbian interior, perhaps from Stari Vlah, towards the Croatian border, in the 14th century. In August 1417, Venetian authorities were concerned with the "Morlachs and other Slavs" from the hinterland, that were a threat to security in Sebenico (Šibenik).

16th century

As many former inhabitants of the Austrian-Ottoman borderland fled northwards or were captured by the Ottoman invaders, they left unpopulated areas. The Austrian Empire encouraged people, mostly Orthodox Serbs from the Ottoman Empire, to settle as free peasant soldiers, establishing the Military Frontiers (Militärgrenze) in 1522 (hence they were known as Grenzers, krajišnici). The militarized frontier would serve as a buffer against Ottoman incursions. The Military frontiers had territory of modern Croatia, Serbia, Romania and Hungary. The colonists were granted small tracts of land, exempted from some obligations, and were to retain a share of all war booty. The Grenzers elected their own captains (vojvode) and magistrates (knezovi). All Orthodox settlers were promised freedom of worship. By 1538, the Croatian and Slavonian Military Frontier were established. Serbs acted as the cordon sanitaire against Ottoman incursions. The Military frontiers are virtually identical to the present Serb settlements in Croatia (war-time Republic of Serbian Krajina).

In 1579, several groups of Morlachs, understood as Serb tribes in Dalmatia, migrated to the Austrian Croatian Military Frontier and requested to be employed as military colonists. Initially, there were some tensions between these and the established Uskoks. In 1593, provveditore generale Cristoforo Valier mentioned three nations constituting the Uskoks, the "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".

17th century

In the 17th-century, Stojan Janković was one of the Morlach leaders in Dalmatia. In the summer of 1685, Cosmi, the Archbishop of Split, wrote that Stojan had brought 300 families with him to Dalmatia, and also that around Trogir and Split there were 5000 refugees from Turkish lands, without food - seen as a serious threat to the defense of Dalmatia. Grain sent by the Pope proved insufficient, and the Serbs were forced to launch expeditions into Turkish territory.

18th—19th century

In the 1851 census of Dalmatia, the Morlachs, citizens of Ragusa and inhabitants of Dalmatian coast and islands declared themselves Serbs.

Legacy

The population that Venetians called Morlachs were absorbed in the Serbian and Croatian nationalities by the 19th century. According to the 1991 Croatian census, 22 people declared themselves as Morlachs. There was no data on Morlachs in the 2001 Croatian census.

See also

Annotations

- "Vlachs", referring to pastoralists, was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire and later. Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name 'Vlach' didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs but also to cattle breeders in general. A letter of Emperor Ferdinand, sent on November 6, 1538, to Croatian ban Petar Keglević, in which he wrote "Captains and dukes of the Rasians, or the Serbs, or the Vlachs, who usually call themselves the Serbs". Serbs that took refuge in the Habsburg Krajina, were called "Vlachs" by Croats. In the work "About the Vlachs" from 1806, Metropolitan Stevan Stratimirović states that Roman Catholics from Croatia and Slavonia scornfully used the name 'Vlach' for "the Slovenians (Slavs) and Serbs, who are of our, Eastern confession (Orthodoxy)", and that "the Turks in Bosnia and Serbia also call every Bosnian or Serbian Christian a Vlach" (T. Đorđević, 1984:110). That the name 'Vlach' was used to signify the Serbs is testified by Vuk Karadžić as well.

References

- ^ Fine 2006, pp. 360-361

- ^ Imagology. p. 235. ISBN 9042023171.

- Fine 2006

- Listine o odnošajih Južnoga Slavenstva i Mletačke Republike. Vol. III. Zagreb: JAZU. 1872. p. 237.

Prvi se put spominje ime »Morlak« (Morlachi) 1352 godine, 24. lipnja, u pogodbi po kojoj zadarsko vijeće prodaje sol Veneciji, gdje Zadar zadržava dio soli koju Morlaci i drugi izvoze, kopnenim putem.

- THE ENCYCLOPEDAEDIA BRITANNICA. 1929. p. 230.

- Fine 2006, p. 115

- William Safran, The secular and the sacred: nation, religion, and politics, p. 169

- Nicholas J. Miller, 1998, Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War, p. 10

- Gunther Erich Rothenberg (1960). The Austrian military border in Croatia, 1522-1747. University of Illinois Press. p. 50.

- Fine 2006, p. 218

- ^ Ivan Ninić. Migrations in Balkan history. p. 80.

- Mile Dakić (1994). The Serbian Krayina: Historical Roots and Its Birth. Iskra. p. 12.

- Croatian 2001 census, detailed classification by nationality

- ^ (Document). 2003.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)

Sources

- John Van Antwerp Fine (2006). When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans. ISBN 0472025600.

- Norman M. Naimark; Holly Case (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4594-9.

External links

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911). "Dalmatia".