| Revision as of 21:15, 18 June 2014 editR'n'B (talk | contribs)Administrators421,152 editsm Disambiguating links to Jacobian (help needed; help needed) using DisamAssist.← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:15, 20 June 2014 edit undoAlexandre.willame (talk | contribs)32 edits →The Jacobian inverse technique: fixed a couple of errors and notations.Next edit → | ||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

| === The Jacobian inverse technique === | === The Jacobian inverse technique === | ||

| The ]{{dn|date=June 2014}} inverse technique is a simple yet effective way of implementing inverse kinematics. Let there be <math>m</math> variables that govern the forward-kinematics equation, i.e. the position function. These variables may be joint angles, lengths, or other arbitrary real values. If the IK system lives in a 3-dimensional space, the position function can be viewed as a mapping <math>p( |

The ]{{dn|date=June 2014}} inverse technique is a simple yet effective way of implementing inverse kinematics. Let there be <math>m</math> variables that govern the forward-kinematics equation, i.e. the position function. These variables may be joint angles, lengths, or other arbitrary real values. If the IK system lives in a 3-dimensional space, the position function can be viewed as a mapping <math>p(x): \Re^m \rightarrow \Re^3</math>. Let <math>p_0 = p(x_0)</math> give the initial position of the system, and | ||

| <math>p_1 = p(x_0 + \Delta x)</math> | |||

| For small <math>\sigma</math>-vectors, the series expansion of the position function gives: | |||

| be the goal position of the system. The Jacobian inverse technique compute iteratively an estimate of <math>\Delta x</math> that minimize the error given by <math>||p(x_0 + \Delta x) - p_1||</math>. | |||

| ⚫ | <math>p( |

||

| For small <math>\Delta x</math>-vectors, the series expansion of the position function gives: | |||

| ⚫ | <math>p(x_1) \approx p(x_0) + J_p(\hat{x}_0)\Delta x</math> | ||

| Where <math>J_p(x_0)</math> is the (3 x m) ] matrix of the position function at <math>x_0</math>. | |||

| Note that the (i, k)-th entry of the Jacobian matrix can be determined numerically: | Note that the (i, k)-th entry of the Jacobian matrix can be determined numerically: | ||

| <math>\frac{\partial p_i}{\partial x_k} \approx \frac{p_i(x_{0,k} + h) - p_i( |

<math>\frac{\partial p_i}{\partial x_k} \approx \frac{p_i(x_{0,k} + h) - p_i(x_0)}{h}</math> | ||

| Where <math>p_i( |

Where <math>p_i(x)</math> gives the i-th component of the position function, <math>x_{0,k} + h</math> is simply <math>x_0</math> with a small delta added to its k-th component, and <math>h</math> is a reasonably small positive value. | ||

| Taking the ] of the Jacobian and re-arranging terms results in: | Taking the ] of the Jacobian (computable using a ]) and re-arranging terms results in: | ||

| <math>\ |

<math>\Delta x \approx J_p^+(x_0)\Delta p</math> | ||

| Where <math>\ |

Where <math>\Delta p = p(x_0 + \Delta x) - p(x_0)</math>. | ||

| Applying the inverse Jacobian method once will result in a very rough estimate of the desired <math>\ |

Applying the inverse Jacobian method once will result in a very rough estimate of the desired <math>\Delta x</math>-vector. A ] should be used to scale this <math>\Delta x</math> to an acceptable value. The estimate for <math>\Delta x</math> can be improved via the following algorithm (known as the ] method): | ||

| <math>\ |

<math>\Delta x_{k+1} = J_p^+(x_k)\Delta p_k</math> | ||

| Once some <math>\ |

Once some <math>\Delta x</math>-vector has caused the error to drop close to zero, the algorithm should terminate. Existing methods based on the ] of the system have been reported to converge to desired <math>\Delta x</math> values using fewer iterations, though, in some cases more computational resources. | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Revision as of 18:15, 20 June 2014

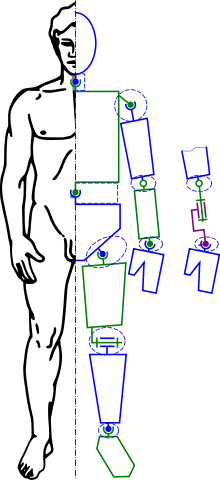

Inverse kinematics refers to the use of the kinematics equations of a robot to determine the joint parameters that provide a desired position of the end-effector. Specification of the movement of a robot so that its end-effector achieves a desired task is known as motion planning. Inverse kinematics transforms the motion plan into joint actuator trajectories for the robot.

The movement of a kinematic chain whether it is a robot or an animated character is modeled by the kinematics equations of the chain. These equations define the configuration of the chain in terms of its joint parameters. Forward kinematics uses the joint parameters to compute the configuration of the chain, and inverse kinematics reverses this calculation to determine the joint parameters that achieves a desired configuration.

For example, inverse kinematics formulas allow calculation of the joint parameters that position a robot arm to pick up a part. Similar formulas determine the positions of the skeleton of an animated character that is to move in a particular way.

Kinematic analysis

Kinematic analysis is one of the first steps in the design of most industrial robots. Kinematic analysis allows the designer to obtain information on the position of each component within the mechanical system. This information is necessary for subsequent dynamic analysis along with control paths.

Inverse kinematics is an example of the kinematic analysis of a constrained system of rigid bodies, or kinematic chain. The kinematic equations of a robot can be used to define the loop equations of a complex articulated system. These loop equations are non-linear constraints on the configuration parameters of the system. The independent parameters in these equations are known as the degrees of freedom of the system.

While analytical solutions to the inverse kinematics problem exist for a wide range of kinematic chains, computer modeling and animation tools often use Newton's method to solve the non-linear kinematics equations.

Other applications of inverse kinematic algorithms include interactive manipulation, animation control and collision avoidance.

Inverse kinematics and 3D animation

Further information: Robotics and Computer animationInverse kinematics is important to game programming and 3D animation, where it is used to connect game characters physically to the world, such as feet landing firmly on top of terrain.

An animated figure is modeled with a skeleton of rigid segments connected with joints, called a kinematic chain. The kinematics equations of the figure define the relationship between the joint angles of the figure and its pose or configuration. The forward kinematic animation problem uses the kinematics equations to determine the pose given the joint angles. The inverse kinematics problem computes the joint angles for a desired pose of the figure.

It is often easier for computer-based designers, artists and animators to define the spatial configuration of an assembly or figure by moving parts, or arms and legs, rather than directly manipulating joint angles. Therefore, inverse kinematics is used in computer-aided design systems to animate assemblies and by computer-based artists and animators to position figures and characters.

The assembly is modeled as rigid links connected by joints that are defined as mates, or geometric constraints. Movement of one element requires the computation of the joint angles for the other elements to maintain the joint constraints. For example, inverse kinematics allows an artist to move the hand of a 3D human model to a desired position and orientation and have an algorithm select the proper angles of the wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints. Successful implementation of computer animation usually also requires that the figure move within reasonable anthropomorphic limits.

Approximating solutions to IK systems

There are many methods of modelling and solving inverse kinematics problems. The most flexible of these methods typically rely on iterative optimization to seek out an approximate solution, due to the difficulty of inverting the forward kinematics equation and the possibility of an empty solution space. The core idea behind several of these methods is to model the forward kinematics equation using a Taylor series expansion, which can be simpler to invert and solve than the original system.

The Jacobian inverse technique

The Jacobian inverse technique is a simple yet effective way of implementing inverse kinematics. Let there be variables that govern the forward-kinematics equation, i.e. the position function. These variables may be joint angles, lengths, or other arbitrary real values. If the IK system lives in a 3-dimensional space, the position function can be viewed as a mapping . Let give the initial position of the system, and

be the goal position of the system. The Jacobian inverse technique compute iteratively an estimate of that minimize the error given by .

For small -vectors, the series expansion of the position function gives:

Where is the (3 x m) Jacobian matrix of the position function at .

Note that the (i, k)-th entry of the Jacobian matrix can be determined numerically:

Where gives the i-th component of the position function, is simply with a small delta added to its k-th component, and is a reasonably small positive value.

Taking the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse of the Jacobian (computable using a singular value decomposition) and re-arranging terms results in:

Where .

Applying the inverse Jacobian method once will result in a very rough estimate of the desired -vector. A line search should be used to scale this to an acceptable value. The estimate for can be improved via the following algorithm (known as the Newton-Raphson method):

Once some -vector has caused the error to drop close to zero, the algorithm should terminate. Existing methods based on the Hessian matrix of the system have been reported to converge to desired values using fewer iterations, though, in some cases more computational resources.

See also

- 321 kinematic structure

- Arm solution

- Forward kinematic animation

- Forward kinematics

- Kinemation

- Jacobian

- Joint constraints

- Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm

- Physics engine

- Pseudoinverse

- Ragdoll physics

- Robot kinematics

- Denavit–Hartenberg parameters

References

- Paul, Richard (1981). Robot manipulators: mathematics, programming, and control : the computer control of robot manipulators. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. ISBN 978-0-262-16082-7.

- J. M. McCarthy, 1990, Introduction to Theoretical Kinematics, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- J. J. Uicker, G. R. Pennock, and J. E. Shigley, 2003, Theory of Machines and Mechanisms, Oxford University Press, New York.

- J. M. McCarthy and G. S. Soh, 2010, Geometric Design of Linkages, Springer, New York.

External links

- Robotics and 3D Animation in FreeBasic Template:Es icon

- Analytical Inverse Kinematics Solver - Given an OpenRAVE robot kinematics description, generates a C++ file that analytically solves for the complete IK.

- Inverse Kinematics algorithms

- Robot Inverse solution for a common robot geometry

- HowStuffWorks.com article How do the characters in video games move so fluidly? with an explanation of inverse kinematics

- 3D Theory Kinematics

- Protein Inverse Kinematics

- Simple Inverse Kinematics example with source code using Jacobian

- Detailed description of Jacobian and CCD solutions for inverse kinematics

variables that govern the forward-kinematics equation, i.e. the position function. These variables may be joint angles, lengths, or other arbitrary real values. If the IK system lives in a 3-dimensional space, the position function can be viewed as a mapping

variables that govern the forward-kinematics equation, i.e. the position function. These variables may be joint angles, lengths, or other arbitrary real values. If the IK system lives in a 3-dimensional space, the position function can be viewed as a mapping  . Let

. Let  give the initial position of the system, and

give the initial position of the system, and

that minimize the error given by

that minimize the error given by  .

.

is the (3 x m)

is the (3 x m)  .

.

gives the i-th component of the position function,

gives the i-th component of the position function,  is simply

is simply  is a reasonably small positive value.

is a reasonably small positive value.

.

.