| Revision as of 15:45, 4 May 2015 editKharkiv07 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers14,606 editsm Reverted edits by 137.85.253.2 (talk) (HG)← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:46, 4 May 2015 edit undo137.85.253.2 (talk) →GenealogyTags: repeating characters nonsense charactersNext edit → | ||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

| * {{flagicon|Kingdom of Prussia}} Knight (with collar) of the ]. | * {{flagicon|Kingdom of Prussia}} Knight (with collar) of the ]. | ||

| Hold my DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD- | |||

| ==Genealogy== | |||

| ===Ancestry=== | |||

| {{Ahnentafel top|width=100%}} | |||

| <center>{{Ahnentafel-compact5 | |||

| |style=font-size: 90%; line-height: 110%; | |||

| |border=1 | |||

| |boxstyle=padding-top: 0; padding-bottom: 0; | |||

| |boxstyle_1=background-color: #fcc; | |||

| |boxstyle_2=background-color: #fb9; | |||

| |boxstyle_3=background-color: #ffc; | |||

| |boxstyle_4=background-color: #bfc; | |||

| |boxstyle_5=background-color: #9fe; | |||

| |1= 1. '''Maximilian I of Mexico''' | |||

| |2= 2. ] | |||

| |3= 3. ] | |||

| |4= 4. ]<br /><small>Francis I of Austria</small> | |||

| |5= 5. ] | |||

| |6= 6. ] | |||

| |7= 7. ] | |||

| |8= 8. ] | |||

| |9= 9. ] | |||

| |10= 10. ] | |||

| |11= 11. ] | |||

| |12= 12. ] | |||

| |13= 13. ] | |||

| |14= 14. ] | |||

| |15= 15. ] | |||

| |16= 16. ]<br /><small>(Francis III Stephen, Duke of Lorraine)</small> | |||

| |17= 17. ]<br /><small>Queen of Hungary & Bohemia</small> | |||

| |18= 18. ] | |||

| |19= 19. ] | |||

| |20= 20. ] (=18) | |||

| |21= 21. ] (=19) | |||

| |22= 22. ] (=16)<br /><small>(Francis III Stephen, Duke of Lorraine)</small> | |||

| |23= 23. ] (=17)<br /><small>Queen of Hungary & Bohemia</small> | |||

| |24= 24. ] | |||

| |25= 25. Princess Caroline of Nassau-Saarbrücken | |||

| |26= 26. ] | |||

| |27= 27. ] | |||

| |28= 28. ] | |||

| |29= 29. Landgravine Caroline Louise of Hesse-Darmstadt | |||

| |30= 30. ] | |||

| |31= 31. ] | |||

| }}</center> | |||

| {{Ahnentafel bottom}} | |||

| ==Endnotes== | ==Endnotes== | ||

Revision as of 15:46, 4 May 2015

Emperor| Maximilian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor | |||||

Emperor Maximiliano around 1865 Emperor Maximiliano around 1865 | |||||

| Emperor of Mexico | |||||

| Reign | 10 April 1864 – 19 June 1867 | ||||

| Predecessor | Monarchy re-established (Benito Juárez, President of Mexico) | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished (Benito Juárez, President of Mexico) | ||||

| Regent | See list | ||||

| Born | (1832-07-06)6 July 1832 Schönbrunn, Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Died | 19 June 1867(1867-06-19) (aged 34) Cerro de las Campanas, Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico | ||||

| Burial | Imperial Crypt, Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Spouse | Charlotte of Belgium | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| Father | Archduke Franz Karl of Austria | ||||

| Mother | Princess Sophie of Bavaria | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Maximilian (Spanish: Maximiliano; Born Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was the only monarch of the Second Mexican Empire. He was a younger brother of the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph I. After a distinguished career in the Austrian Navy, he entered into a scheme with Napoleon III of France to rule Mexico. France had invaded Mexico in 1861, with the implicit support and approval of other European powers, as part of the War of the French Intervention. Seeking to legitimize French rule, Napoleon III invited Maximilian to establish a new Mexican monarchy. With the support of the French army and a group of conservative Mexican monarchists, Maximilian traveled to Mexico where he declared himself Emperor of Mexico on 10 April 1864.

Many foreign governments, including that of the United States, refused to recognize his administration. Maximilian's Second Mexican Empire was widely considered a puppet of France. Additionally, the Mexican Republic was never entirely defeated; Republican forces led by President Benito Juárez continued to be active throughout Maximilian's rule. With the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the United States began to be able to more explicitly aid the democratic forces of Juárez; things became even worse for Maximilian's Empire after the French withdrew their armies in 1866. The Mexican Empire collapsed, and Maximilian was captured and executed in 1867. His wife Charlotte of Belgium (Carlota) had left for Europe earlier to try to build support for her husband's regime; she suffered an emotional collapse after his death and was declared insane.

Early life

Birth

Maximilian was born on 6 July 1832 in the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, capital of the Austrian Empire. He was baptized the following day and given the full name Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph. The first name honored his godfather and paternal uncle, the future Emperor Ferdinand I and the second honored his maternal grandfather, King Maximilian I of Bavaria.

His father was Archduke Franz Karl, the second surviving son of the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (after 1804, ruling the Austrian Empire as Franz I). Maximilian was thus a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, a female-line cadet branch of the House of Habsburg. His mother was Sophie, a Bavarian princess of the House of Wittelsbach. Intelligent, ambitious and strong-willed, Sophie had little in common with her husband, whom historian Richard O'Conner characterized as "an amiably dim fellow whose main interest in life was consuming bowls of dumplings drenched in gravy." Despite their different personalities, the marriage was fruitful, and after four miscarriages, four sons—including Maximilian—would reach adulthood.

Rumors at the court stated that Maximilian was in fact the product of an extramarital affair between his mother and his first cousin Napoleon II (then known as the Duke of Reichstadt), only son of Napoleon Bonaparte; the Duke's mother was Archduchess Marie Louise, daughter of Francis II. The existence of an illicit affair between Sophie and Napoleon II, and any possibility that Maximilian was conceived from such a union, are widely dismissed by historians.

Education

Adhering to traditions inherited from the Spanish court during Habsburg rule, Maximilian's upbringing was supervised by an aya (governess, also rendered in English as Ayah) until his sixth birthday. Afterwards, his education was entrusted to a tutor. Most of Maximilian's day was spent in study. The thirty-two hours per week of classes at age 7 steadily grew until it reached fifty-five hours per week by the time he was 17. The disciplines were diverse: ranging from history, geography, law and technology, to languages, military studies, fencing and diplomacy. In addition to his native German, he eventually learned to speak Hungarian, Slovak, English, French, Italian and Spanish. From an early age, Maximilian tried to surpass his older brother Franz Joseph (Francis Joseph) in everything; attempting to prove to all that he was the better qualified and deserving of more than second place status.

The highly restrictive environment of the Austrian court was not enough to repress Maximilian's natural openness. He was joyful, highly charismatic and able to captivate those around him with ease. Although he was a charming boy, he was also undisciplined. He mocked his teachers and was often the instigator of pranks—even including his uncle, Emperor Ferdinand I, among his victims. Nonetheless Maximilian was very popular. His attempts to outshine his older brother and ability to charm opened a rift with the aloof and self-contained Franz Joseph that would widen as years passed, and the times when both were close friends in childhood would be all but forgotten.

In 1848, revolutions erupted across Europe. In the face of protests and riots, Emperor Ferdinand I abdicated in favor of Maximilian's brother, who became Franz Joseph I. Maximilian accompanied him on campaigns to put down rebellions throughout the Empire. Only in 1849 would the revolution be stamped out in Austria, with hundreds of rebels executed and thousands imprisoned. Maximilian was horrified at what he regarded as senseless brutality and openly complained about it. He would later remark: "We call our age the Age of Enlightenment, but there are cities in Europe where, in the future, men will look back in horror and amazement at the injustice of tribunals, which in a spirit of vengeance condemned to death those whose only crime lay in wanting something different to the arbitrary rule of governments which placed themselves above the law."

Career in the Austrian Navy

Commander in Chief

Maximilian was a particularly clever boy who displayed considerable culture in his taste for the arts, and he demonstrated an early interest in science, especially botany. When he entered military service, he was trained in the Austrian Navy. He threw himself into this career with so much zeal that he quickly rose to high command.

He was made a lieutenant in the navy at the age of eighteen. In 1854, he sailed as commander in the corvette Minerva, on an exploring expedition along the coast of Albania and Dalmatia. Maximilian was especially interested in the maritime and undertook many long-distance journeys (for Brazil) on the frigate Elisabeth. In 1854, he was only 22 years—as a younger brother of the Emperor, and thus a member of the ruling family—he was appointed as commander in chief of the Austrian Navy (1854–1861), which he reorganized in the following years. Like Archduke Friedrich (1821–1847) before him, Maximilian had a keen private interest in the fleet, and with him the Austrian naval force gained an influential supporter from the ranks of the Imperial Family. This was crucial as sea power was never a priority of Austrian foreign policy and the navy itself was relatively little known or supported by the public. It was only able to draw significant public attention and funds when it was actively supported by an imperial prince. As Commander-in-Chief, Maximilian carried out many reforms to modernise the naval forces, and was instrumental in creating the naval port at Trieste and Pola (now Pula) as well as the battle fleet with which admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff would later secure his victories. He also initiated a large-scale scientific expedition (1857–1859) during which the frigate SMS Novara became the first Austrian warship to circumnavigate the globe.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byFranz von Wimpffen | Commander-in-Chief of the Austro-Hungarian Naval Fleet 1854–1861 |

Succeeded byLudwig von Fautz |

| Preceded byFranz von Wimpffen | Chief of the Naval Section 1861–1864 |

Succeeded byLudwig von Fautz |

Viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia

In his political views, Archduke Maximilian was very much influenced by the progressive ideas in vogue at the time. He had a reputation as a liberal, and this led, in February 1857, to his appointment as viceroy of the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia.

On 27 July 1857, in Brussels (Belgium) Archduke Maximilian married his second cousin, Princess Charlotte of Belgium (later known as Empress Carlota of Mexico), the daughter of Leopold I, King of the Belgians and Louise-Marie of France. She was first cousin to both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Maximilian and Charlotte had no children together.

They lived as the Austrian regents in Milan or Viceroys of Lombardy-Venetia from 1857 until 1859, when Emperor Franz Josef dismissed Maximilian from this post. The emperor was angered by the liberal policies pursued by his brother in Italy. Shortly after his dismissal, Austria lost control of most of its Italian possessions. Maximilian then retired to Trieste, near which he built the castle, Miramare.

Emperor of Mexico

Offer of the Mexican crown

See also: Imperial Crown of Mexico

In 1859, Ferdinand Maximilian was first approached by Mexican monarchists—members of the Mexican aristocracy, led by local nobleman José Pablo Martínez del Río—with a proposal to become the Emperor of Mexico. The Habsburg family had ruled the Viceroyalty of New Spain before Mexican independence, so Maximilian was considered to have more potential legitimacy than other royalty, but Maximilian was unlikely to ever rule in Europe due to his elder brother. In Paris, 20 October 1861, Maximilian received a letter from Gutierrez de Estrada asking him to take the Mexican throne. He did not accept at first, but sought to satisfy his restless desire for adventure with a botanical expedition to the tropical forests of Brazil. However, Maximilian changed his mind after the French intervention in Mexico. At the invitation from Napoleon III and after General Élie-Frédéric Forey's capture of Mexico City and the plebiscite which confirmed his proclamation of the empire, Maximilian consented to accept the crown in October 1863 (Ferdinand Maximilian was not told of the dubious nature of the plebiscite, whose result was imposed by French troops occupying most of the territory). His decision involved the loss of all his nobility rights in Austria, though he was not informed of this until just before he left. Archduchess Charlotte was thereafter known as "Her Imperial Majesty Empress Carlota".

Reign in Mexico

See also: Second Mexican EmpireIn April 1864, Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian stepped down from his duties as Chief of Naval Section of the Austrian Navy. He traveled from Trieste aboard SMS Novara, escorted by the frigates SMS Bellona (Austrian) and Themis (French), and the Imperial yacht Phantasie led the warship procession from his palace at Miramare out to sea. They received a blessing from Pope Pius IX, and Queen Victoria ordered the Gibraltar garrison to fire a salute for Maximilian's passing ship.

The new emperor of Mexico landed at Veracruz on 21 May 1864, and received a cold reception from the townspeople. Vera Cruz was a liberal town, and the liberal voters were opposed to having Maximilian on the throne. He had the backing of Mexican conservatives and Napoleon III, but from the very outset he found himself involved in serious difficulties since the Liberal forces led by President Benito Juárez refused to recognize his rule. There was continuous warfare between his French troops and the Republicans.

The Imperial couple chose as their seat Mexico City. The Emperor and Empress set up their residence at Chapultepec Castle, located on the top of a hill formerly at the outskirts of Mexico City that had been a retreat of Aztec emperors. Maximilian ordered a wide avenue cut through the city from Chapultepec to the city center; originally named Paseo de la Emperatriz, it is today Mexico City's famous boulevard, Paseo de la Reforma. He also acquired a country retreat at Cuernavaca. The royal couple made plans to be crowned at the Catedral Metropolitana but, due to the constant instability of the regime, the coronation was never carried out. Maximilian was shocked by the living conditions of the poor in contrast to the magnificent haciendas of the upper class. Empress Carlota began holding parties for the wealthy Mexicans to raise money for poor houses. One of Maximilian's first acts as Emperor was to restrict working hours and abolish child labour. He cancelled all debts for peasants over 10 pesos, restored communal property and forbade all forms of corporal punishment. He also broke the monopoly of the Hacienda stores and decreed that henceforth peons could no longer be bought and sold for the price of their debt.

As Maximilian and Carlota had no children, they adopted Agustín de Iturbide y Green and his cousin Salvador de Iturbide y de Marzán, both grandsons of Agustín de Iturbide, who had briefly reigned as Emperor of Mexico in the 1820s. They gave young Agustín the title of "His Highness, the Prince of Iturbide" and intended to groom him as heir to the throne. However, he never intended to give the crown to the Iturbides because he considered that they were not of royal blood. It was all a charade directed to his brother Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria, as he explained himself: either Karl gave him one of his sons as an heir, or he would give everything to the Iturbide children.

To the dismay of his conservative allies, Maximilian upheld several liberal policies proposed by the Juárez administration – such as land reforms, religious freedom, and extending the right to vote beyond the landholding class. At first, Maximilian offered Juárez an amnesty if he would swear allegiance to the crown, even offering the post of Prime Minister, which Juárez refused. Later, Maximilian ordered all captured followers of Juárez to be shot, in response to the Republican practice of executing anyone who was a supporter of the Empire. In the end, it proved to be a tactical mistake that only exacerbated opposition to his regime.

After the end of the American Civil War, the United States government used increasing diplomatic pressure to persuade Napoleon III to end French support of Maximilian and to withdraw French troops from Mexico. Washington began supplying partisans of Juárez and his ally Porfirio Díaz by "losing" arms depots for them at El Paso del Norte at the Mexican border. The prospect of a United States invasion to reinstate Juárez caused a large number of Maximilian's loyal adherents to abandon the cause and leave the capital.

Meanwhile, Maximilian invited ex-Confederates to move to Mexico in a series of settlements called the "Carlota Colony" and the New Virginia Colony with a dozen others being considered, a plan conceived by the internationally renowned U.S. Navy oceanographer and inventor Matthew Fontaine Maury. Maximilian also invited settlers from "any country" including Austria and the other German states.

Maximilian issued his Black Decree on October 3, 1865. Its first article stated that: "All individuals forming a part of armed bands or bodies existing without legal authority, whether or not proclaiming a political pretext, whatever the number of those forming such band, or its organization, character, and denomination, shall be judged militarily by the courts martial. If found guilty, even though only of the fact of belonging to an armed band, they shall be condemned to capital punishment, and the sentence shall be executed within twenty-four hours". It is calculated that more than eleven thousand of Juarez's supporters were executed as a result of the Black Decree, but at the end it only inflamed the Mexican Resistance.

Nevertheless, by 1866, the imminence of Maximilian's abdication seemed apparent to almost everyone outside Mexico. That year, Napoleon III withdrew his troops in the face of Mexican resistance and U.S. opposition under the Monroe Doctrine, as well as increasing his military contingent at home to face the ever growing Prussian military and Bismarck. Carlota travelled to Europe, seeking assistance for her husband's regime in Paris and Vienna and, finally, in Rome from Pope Pius IX. Her efforts failed, and she suffered a deep emotional collapse and never went back to Mexico. After her husband was executed by Republicans the following year, she spent the rest of her life in seclusion, never admitting her husband's death, first at Miramare Castle near Trieste, Italy, and then at Bouchout Castle in Meise, Belgium, where she died on 19 January 1927.

Downfall

Though urged to abandon Mexico by Napoleon III himself, whose troop withdrawal from Mexico was a great blow to the Mexican Imperial cause, Maximilian refused to desert his followers. Maximilian allowed his followers to determine whether or not he abdicated. Faithful generals such as Miguel Miramón, Leonardo Márquez, and Tomás Mejía vowed to raise an army that would challenge the invading Republicans. Maximilian fought on with his army of 8,000 Mexican loyalists. Withdrawing, in February 1867, to Santiago de Querétaro, he sustained a siege for several weeks, but on May 11 resolved to attempt an escape through the enemy lines. This plan was sabotaged by Colonel Miguel López who was bribed by the Republicans to open a gate and lead a raiding party through with the agreement that Maximilian would be allowed to escape.

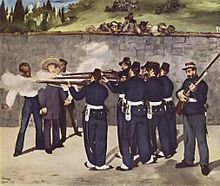

The city fell on 15 May 1867 and Maximilian was captured the next morning after the failure of an attempt to escape through Republican lines by a loyal hussar cavalry brigade led by Felix Salm-Salm. Following a court-martial, he was sentenced to death. Many of the crowned heads of Europe and other prominent figures (including the eminent liberals Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi) sent telegrams and letters to Mexico pleading desperately for the Emperor's life to be spared. Although he liked Maximilian on a personal level, Juárez refused to commute the sentence in view of the Mexicans who had been killed fighting against Maximilian's forces, and because he believed it was necessary to send a message that Mexico would not tolerate any government imposed by foreign powers. Felix Salm-Salm and his wife masterminded a plan and bribed the jailors to allow Maximilian to escape execution. However, Maximilian would not go through with the plan because he felt that shaving his beard to avoid recognition woud ruin his dignity if he were to be recaptured. The sentence was carried out in the Cerro de las Campanas on the morning of 19 June 1867, when Maximilian, along with Generals Miramón and Mejía, were executed by a firing squad. He spoke only in Spanish and gave his executioners a portion of gold not to shoot him in the head so that his mother could see his face. His last words were, "I forgive everyone, and I ask everyone to forgive me. May my blood which is about to be shed, be for the good of the country. Viva Mexico, viva la independencia!". Generals Miramón and Mejía were shot after him. Both died shouting, "Long live the Emperor."

Burial

After his execution, Maximilian's body was embalmed and displayed in Mexico. Early the following year, the Austrian admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff was sent to Mexico aboard SMS Novara to take the former emperor's body back to Austria. After arriving in Trieste, the coffin was taken to Vienna and buried in the Imperial Crypt on 18 January 1868.

Legacy

Maximilian has been praised by some historians for his liberal reforms, his genuine desire to help the people of Mexico, his refusal to desert his loyal followers, and his personal bravery during the siege of Querétaro. However, other researchers consider him short-sighted in political and military affairs, and unwilling to restore democracy in Mexico even during the imminent collapse of the Second Mexican Empire. Today, anti-republican and anti-liberal far right groups who advocate the Second Mexican Empire, such as the Nationalist Front of Mexico, are reported to gather every year in Querétaro to commemorate the execution of Maximilian and his followers. Maximilian is portrayed in the 1934 Mexican film Juárez y Maximiliano by Enrique Herrera and the 1939 American film Juarez by Brian Aherne. He also appeared in one scene in the 1954 American film Vera Cruz, played by George Macready. In the Mexican telenovela "El Vuelo del Águila", Maximilian was portrayed by Mexican actor Mario Iván Martínez.

Titles, styles, honours and arms

| Styles of Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sire |

Titles and styles

- 6 July 1832 – 10 April 1864: His Imperial and Royal Highness Imperial Prince & Archduke Maximilian of Austria, Prince Royal of Hungary and Bohemia

- 10 April 1864 – 19 June 1867: His Imperial Majesty The Emperor of Mexico

Full title as Emperor

His Imperial Majesty Don Maximiliano I (Maximilian I), By the Grace of God and will of the people, Emperor of Mexico.

Honors

Mexican Empire

Emperor Maximilian I was Grand Master of the following Mexican Orders:

Foreign

Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross.

Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross. Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword.

Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword. Grand Cross (First Class) of the Order of the Red Eagle.

Grand Cross (First Class) of the Order of the Red Eagle. Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order.

Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order. Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen.

Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen. Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur.

Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur. Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit.

Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit. Grand Cordon (military) of the Order of Leopold.

Grand Cordon (military) of the Order of Leopold. Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer.

Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer. Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Joseph.

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Joseph. Grand Cross of the House Order of Henry the Lion.

Grand Cross of the House Order of Henry the Lion. Grand Cross of the Philip the Magnanimous.

Grand Cross of the Philip the Magnanimous. Grand Cross of the Order of Malta.

Grand Cross of the Order of Malta. Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle.

Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle. Knight of the Order of Saint Januarius.

Knight of the Order of Saint Januarius. Knight of the House Order of Fidelity.

Knight of the House Order of Fidelity. Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert.

Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert. Knight (with collar) of the Royal Order of the Seraphim.

Knight (with collar) of the Royal Order of the Seraphim. Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown.

Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown. Knight of the Order of St. George.

Knight of the Order of St. George. Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky.

Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky. Knight (First Class) of the Order of Saint Stanislaus.

Knight (First Class) of the Order of Saint Stanislaus. Knight of the Order of the White Eagle.

Knight of the Order of the White Eagle. Knight of the Order of St. Andrew.

Knight of the Order of St. Andrew. Knight (First Class) of the Order of St. Anna.

Knight (First Class) of the Order of St. Anna. Knight (with collar) of the Order of the Black Eagle.

Knight (with collar) of the Order of the Black Eagle.

Hold my DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD-

Endnotes

- "Such an easy assumption of an improbable sexual relationship", said Alan Palmer, "fails to understand the nature of the attachment binding" Sophie and Reichstadt, who saw themselves as alien misfits stranded in a foreign court. To Palmer, their "confidences were those of a brother and elder sister rather than of lovers." "There is no documentary evidence to suggest that she and the Duke of Reichstadt were ever lovers", according to Joan Haslip. "Whether the young Napoleon was actually the father of Maximilian could only be the subject of fascinating conjecture, something for courtiers and servants to gossip about on the long winter nights in the Hofburg ", said Richard O'Connor. "There is not a shred of evidence to support the rumors", affirmed Jasper Ridley. "It was said that Sophie confessed", continued Ridley, "in a letter to her father confessor, that Maximilian was the son of Napoleon, and that the letter was found and destroyed in 1859, but there is no reason to believe this story ... would she have had a sexual relationship with a boy whom she regarded as a child and a younger brother?" The birth of two more sons after the death of Reichstadt in 1832 lessened even more the credibility of these claims.

Footnotes

- Derecho Mexicano, Jacinto Pallares, Mexico ISBN 1-162-47704-0

- Royal Ark

- Haslip 1972, p. 6.

- Hyde 1946, p. 4.

- Corti 1929, p. 41.

- Haslip 1972, pp. 6–7.

- Hyde 1946, p. 5.

- Palmer 1994, pp. 3, 5.

- ^ Palmer 1994, p. 3.

- O'Connor 1971, p. 29.

- Haslip 1972, p. 7.

- ^ Ridley 2001, p. 44.

- Hyde 1946, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hyde 1946, p. 7.

- Hall 1868, p. 17.

- ^ Haslip 1972, p. 17.

- Haslip 1972, p. 11.

- Haslip 1972, pp. 14–15.

- Haslip 1972, p. 29.

- ^ Hyde 1946, p. 13.

- Haslip 1972, p. 31.

- Haslip 1972, p. 34.

- Hyde 1946, p. 14.

- Antonio Schmidt-Brentano DocView.axd? CobId = 23130The Austrian K.K. generals 1816-1918. Austrian State Archives, Vienna 2007, p 130 (PDF).

- Antonio Schmidt-Brentano The Austrian admirals Volume I, 1808–1895, Library Verlag, Osnabrück 1997, pp. 93–104.

- Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria Maximilian, Archduke of Austria:From My Life Reiseskizzen, aphorisms, poems, Volume 6:.Reiseskizzen Part 11 2 Edition. Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig, 1867

- Antonio Schmidt-Brentano: Die K.K bzw. K.u.K Generalität 1816–1918. Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Wien 2007, S. 130 (PDF).

- ^ Maximilian in Mexico

- Haslip, Joan, Imperial Adventurer – Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, London, 1971, ISBN 0-297-00363-1

- Parkes 1960, p. 261.

- ^ José Manuel Villalpando, Alejandro Rosas (2011), Presidentes de México, Grupo Planeta Spain, pp. pages are not numbered, ISBN 9786070707582

{{citation}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Paul H. Reuter, "United States-French Relations Regarding French Intervention in Mexico: From the Tripartite Treaty to Queretaro," Southern Quarterly (1965) 6#4 pp 469-489

- Rolle, Andrew F., The Lost Cause: The Confederate Exodus to Mexico, University of Oklahoma Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-8061-1961-8.

- Donald W. Miles (2006), Cinco de Mayo: What is Everybody Celebrating? : the Story Behind Mexico's Battle of Puebla, iUniverse, p. 196, ISBN 9780595392414

- Jasper Ridley (1993), Maximilian and Juárez, Constable, p. 229, ISBN 9780094720701

- "Charlotte of Mexico's Misfortune", New York Times, March 6, 1885.

- "Belgium Mourns for Dead Empress; Tragedy of Life of Charlotte, Wife of Maximilian, Is Recalled", New York Times, January 19, 1927.

- Maximilian and Carlota by Gene Smith, ISBN 0-245-52418-5, ISBN 978-0-245-52418-9

- Parkes 1960, p. 273.

- Giving executer(s) a portion of gold/silver is well-established among European aristocracy since medieval time and not an act of desperation. In other accounts, Maximilian calmly said, "aim well", to the firing squad and met his death with dignity.

- "Homage to the Martyrs of the Second Mexican Empire".

- "El vuelo del águila".

- Haslip 1972, p. 4.

- O'Connor 1971, p. 31.

- ^ Ridley 2001, p. 45.

References

- Corti, Egon Caesar Count (1929). Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico. Vol. 1–2. New York and London: Alfred A. Knopf.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hall, Frederick (1868). Invasion of Mexico by the French; and the reign of Maximilian I., with a sketch of the Empress Carlota. New York: James Miller.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haslip, Joan (1972). The Crown of Mexico: Maximilian and His Empress Carlota. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-086572-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hyde, H. Montgomery (1946). Mexican Empire: the history of Maximilian and Carlota of Mexico. London: Macmillan & Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kératry, Émile (1868). The rise and fall of the Emperor Maximilian. A narrative of the Mexican Empire, 1861-7, with the imperial correspondence. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Connor, Richard (1971). The Cactus Throne: the tragedy of Maximilian and Carlotta. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palmer, Alan (1994). Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-665-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parkes, Henry (1960). A History of Mexico. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-08410-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ridley, Jasper (2001). Maximilian & Juarez. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-150-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Recollections of my life by Maximilian I of Mexico Vol. I at archive.org

- Recollections of my life by Maximilian I of Mexico Vol. II at archive.org

- Recollections of my life by Maximilian I of Mexico Vol. III at archive.org

| Maximilian I of Mexico House of Habsburg-LorraineCadet branch of the House of HabsburgBorn: 6 July 1832 Died: 19 June 1867 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| VacantTitle last held byAgustín I | Emperor of Mexico 10 April 1864 – 15 May 1867 |

Monarchy abolished Restoration of Republic |

| Government offices | ||

| VacantTitle last held byFranz Joseph I | Viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia 1857–1859 |

Succeeded byFranz Joseph I in Venetia |

| Succeeded byVictor Emmanuel II in Lombardy | ||

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded byJuan Nepomuceno Almonte Pelagio Antonio de Labastida y Dávalos José Mariano Salasas regents |

Mexican head of state as Emperor of Mexico 29 May 1864 – 15 May 1867 |

Succeeded byBenito Juárezas President of Mexico |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| VacantTitle last held byAgustin II | — TITULAR — Emperor of Mexico 15 May 1867 – 19 Jun 1867 |

Succeeded byAgustín III |

| Austrian archdukes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generations are numbered by male-line descent from the first archdukes. Later generations are included although Austrian titles of nobility were abolished in 1919. | |||||||

| 1st generation | |||||||

| 2nd generation | |||||||

| 3rd generation | |||||||

| 4th generation | |||||||

| 5th generation | |||||||

| 6th generation | |||||||

| 7th generation | |||||||

| 8th generation | |||||||

| 9th generation | |||||||

| 11th generation | |||||||

| 12th generation | |||||||

| 13th generation | |||||||

| 14th generation | |||||||

| 15th generation | |||||||

| 16th generation |

| ||||||

| 17th generation |

| ||||||

| 18th generation |

| ||||||

| 19th generation |

| ||||||

| |||||||

- Mexican emperors

- 19th-century Mexican people

- 19th-century rulers in North America

- French intervention in Mexico

- Independent Mexico

- 19th century in Mexico

- Austrian royalty

- History of Mexico

- Executed reigning monarchs

- Austrian people executed by firing squad

- House of Habsburg

- House of Habsburg-Lorraine

- Roman Catholic monarchs

- Austro-Hungarian admirals

- Mexican people of Austrian descent

- People from Hietzing

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Pretenders to the Mexican throne

- Titles of nobility in the Americas

- Mexican people executed by firing squad

- People executed by Mexico by firing squad

- 1832 births

- 1867 deaths

- Grand Masters of the Order of the Mexican Eagle

- Grand Masters of the Order of Saint Charles (Mexico)

- Grand Masters of the Order of Guadalupe

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Knights of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Joseph

- Recipients of the Order of the Rue Crown

- World Digital Library related

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Red Eagle

- 19th-century men

- 19th-century monarchs in North America