| Revision as of 22:00, 6 October 2006 edit89.172.230.252 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:31, 13 October 2006 edit undoDavewild (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,789 editsm →[]: disambiguateNext edit → | ||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

| Pagania is described as a late baptised Slavic land. | Pagania is described as a late baptised Slavic land. | ||

| The ]-like people of ]/Narenta (named after river ]) expressed their buccaneering capabilities by pirateering the Venetian-controlled Adriatic between ] and ], while the Venetian fleet was off-broad, in the ] waters. As soon as the ] of the ] returned, the Neretvians fell back. The Neretvians were also known as '']'', because by the time of their ], all ] already accepted ]. One of their leaders was ] in ]. As soon as the chances were good, the Neretvians would immediately embark on new raids. In ] and ], they have cought and killed several Venetian traders returning from ]. To punish the Neretvians, the ] ] had launched a military expedition against them in ]. The war went on together with the ], but a truce was signed very soon, although, only with the Dalmatian Croats and some of the Pagan tribes. In ], the ] had launched an expedition against the Neretvian Prince ''Ljudislav'', but utterly failed. In 846, a new operation is launched that raided the ] land of ], destroying one of her most important cities - ''Kaorle'', although this did not end the Neretvian resistance, as they continued to mercilessly raid and steal from the Venetian occupators. | The ]-like people of ]/Narenta (named after river ]) expressed their buccaneering capabilities by pirateering the Venetian-controlled Adriatic between ] and ], while the Venetian fleet was off-broad, in the ] waters. As soon as the ] of the ] returned, the Neretvians fell back. The Neretvians were also known as '']'', because by the time of their ], all ] already accepted ]. One of their leaders was ] in ]. As soon as the chances were good, the Neretvians would immediately embark on new raids. In ] and ], they have cought and killed several Venetian traders returning from ]. To punish the Neretvians, the ] ] had launched a military expedition against them in ]. The war went on together with the ], but a truce was signed very soon, although, only with the Dalmatian Croats and some of the Pagan tribes. In ], the ] had launched an expedition against the Neretvian Prince ''Ljudislav'', but utterly failed. In 846, a new operation is launched that raided the ] land of ], destroying one of her most important cities - ''Kaorle'', although this did not end the Neretvian resistance, as they continued to mercilessly raid and steal from the Venetian occupators. | ||

| Neretvia was subjected to ] rulers like Petar Gojniković throughought the ]. Neretvians then aligned themselves with ] ] of ] in the first half of the ]. After King Trpimir's death, Pagania would eventually be incorporated directly into the ] of Prince ] from the ] in ]-]. The ]n period marked Neretvia's Golden Age. In ] King Krešimir of ] died, and Civil War erupted. The Neretvians used Prince Časlav's annexations of Croatian territories and took ], ] and ]; also managing to defend their own islands of ], ], ] and ]. In ], ] ] ] of ] dispatched 33 ] against the Neretvians, but the military attempt ended so drasticly, that since that moment ] had to pay taxes regularely to the Neretvian Princes and their supreme rulers. | Neretvia was subjected to ] rulers like Petar Gojniković throughought the ]. Neretvians then aligned themselves with ] ] of ] in the first half of the ]. After King Trpimir's death, Pagania would eventually be incorporated directly into the ] of Prince ] from the ] in ]-]. The ]n period marked Neretvia's Golden Age. In ] King Krešimir of ] died, and Civil War erupted. The Neretvians used Prince Časlav's annexations of Croatian territories and took ], ] and ]; also managing to defend their own islands of ], ], ] and ]. In ], ] ] ] of ] dispatched 33 ] against the Neretvians, but the military attempt ended so drasticly, that since that moment ] had to pay taxes regularely to the Neretvian Princes and their supreme rulers. | ||

Revision as of 19:31, 13 October 2006

This is the history of Dalmatia.

Classical Antiquity

Illyria and the Roman Empire

The history of Dalmatia began when the tribe from which the country derives its name declared itself independent of Gentius, the Illyrian king, and established a republic. Its capital was Delminium (current name Tomislavgrad); its territory stretched northwards from the river Neretva to the river Cetina, and later to the Krka, where it met the confines of Liburnia.

The Roman Empire began its occupation of Illyria in the year 168 B.C., forming the Roman province of Illyricum. In 156 B.C. the Dalmatians were for the first time attacked by a Roman army and compelled to pay tribute. In AD 10, during the reign of Augustus, Illyricum was split into Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south, after the last of many formidable revolts had been crushed by Tiberius in AD 9. This event was followed by total submission and a ready acceptance of the Latin civilization which overspread Illyria.

The province of Dalmatia spread inland to cover all of the Dinaric Alps and most of the eastern Adriatic coast. Its capital was in the city of Salona (Solin). Emperor Diocletian made Dalmatia famous by building a palace for himself a few kilometers south of Salona, in Aspalathos/Spalatum. Other Dalmatian cities at the time were:

- Tarsatica

- Senia

- Vegium

- Aenona

- Iader

- Scardona

- Tragurium

- Aequum

- Oneum

- Issa

- Pharus

- Bona

- Corcyra Nigra

- Narona

- Epidaurus

- Rhizinium

- Acruvium

- Olcinium

- Scodra

- Epidamnus/Dyrrachium

The collapse of the Western Empire left this region subject to Gothic rulers, Odoacer and Theodoric the Great, from 476 to 535, when it was added by Justinian I to the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

Medieval city-states and the country

Following the great Slavic migration into Illyria in the first half of the 7th century, Dalmatia became distinctly divided between two different communities:

- The hinterland populated by Slavic tribes, besides the Romanicized Illyrian natives (and Celtic in the north), roughly Croats to the north and Serbs to south; separated by the Cetina river

- The Byzantine enclaves populated by the native Romance-speaking descendants of Romans and Illyrians, who lived safely in Ragusa, Iadera, Tragurium, Spalatum and some other coastal towns.

These towns remained powerful because they were highly civilized (because of their connection with the Byzantium) and also fortified. The Slavs were at the time barely in the process of becoming Christianized. The two different communities were frequently hostile at first.

The Slavs that migrated soon formed their own realm, the Principality of Dalmatia, ruled by native Princes of Guduscan origin.

In 806 the Principality of Dalmatia was temporarily added to the Frankish Empire, but the cities were restored to Byzantium by the Treaty of Aachen in 812. The treaty had also slightly expanded the Principality of Dalmatia eastwards. The Saracens raided the southernmost cities in 840 and 842, but this threat was eliminated by a common Frankish-Byzantinian campaign of 871.

Liudevit's plight

During the first half of the 9th century, Prince of Pannonia Liudevit TransSavian fought terrifying wars with Prince of Dalmatia, Borna who was a Guduscan. The Guduscans were an indigenous people of Dalmatia. In the heat of battle, the Guduscans have abandoned the Dalmatian Army, and crossed to Prince Liudevit's side, ensuing his victory. Borna's personal guard saved Prince Borna from certain death on the battlefield. Liudevit was soon forced out of his Pannonian realm by the Frankish forces, so he fled to the Serbs, that according to the Frankish historian Einhardt in his Royal Frankish Annals, controlled the greater part of Dalmatia. Although accepted well, Liudevit tricked the local Serbian ruler, killed him and took his land for himself. He did not rule for long, as he was expelled shortly and returned to his land, but had permanently expanded his lands eastwards.

Croatian Dalmatia

Since the 850s the Principality of Dalmatia became known as the Duchy of the Croats. This duchy was also called Coastal Croatia and Dalmatian Croatia. This Duchy, and after 925., Kingdom, had its capitals in Dalmatia: Biaći, Nin, Split, Knin, Solin and elsewhere. Also, the Croatian noble tribes, that had a right to choose Croatian duke (later the king), were from Dalmatia: Karinjani and Lapčani, Polečići, Tugomirići, Kukari, Snačići, Gusići, Šubići (from which later developed very powerful noble family Zrinski), Mogorovići, Lačničići, Jamometići and Kačići. Within the borders of ancient Roman Dalmatia, the Croatian nobles of Krk, or Krčki (from which later developed very powerful noble family Frankopan) were from Dalmatia as well.

The establishment of cordial relations between the cities and the Croatian dukedom seriously began with the reign of Duke Mislav (835), who signed an official peace treaty with Pietro, doge of Venice in 840 and who also started giving land donations to the churches from the cities. Dalmatia's first Croatian Duke, Trpimir, founder of the House of Trpimir and the Duchy of Croats, greatly expanded the new Duchy to include territories all the way to the river of Drina, thereby including entire Bosnia in his wars against the Bulgar Khans and their Serbian subjects. Duke of Croats Tomislav had created the Kingdom of Croatia in 924 or 925, crowned in Tomislavgrad after defending and annexing the Principality of Pannonia. His powerful realm extended influence further southwards to Zachlumia slightly.

Southern Dalmatian Principalities

The southern part of Dalmatia was ruled by the small Slavic Principalities of Pagania/Narenta, Zahumlje/Hum, Travunia and Duklja. Pagania was a minor duchy between Cetina and Neretva. The territories of Zahumlje and Travunia probably spread much further inland and than the current Dalmatia does. Duklja began south of Dubrovnik/Ragusa and spread down to the Skadar Lake. All of these duchies were at the time self-ruled by their Slavic population that was, by religion, mixed pagan and Christian. Duklja, Zahumlje and Travunia were collectively referred to as Red Croatia by De Regno Sclavorum from 753, found in the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja from the late 12th century, while all four are referred to as Serbian lands, their people originating from White Serbia by De Administrando Imperio by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos from around 950. The core part of medieval Croatia was called "White Croatia" and located northwest, between Drniš, Knin and Sinj.

Pagania

The Principality border with Zachlumia at the river of Neretva. It was split on three lesser principalities:

The Pagans also controlled the following islands:

The main Cities in Pagania were:

Pagania is described as a late baptised Slavic land.

The Pirate-like people of Pagania/Narenta (named after river Narenta) expressed their buccaneering capabilities by pirateering the Venetian-controlled Adriatic between 827 and 828, while the Venetian fleet was off-broad, in the Sicilian waters. As soon as the Fleet of the Venetian Republic returned, the Neretvians fell back. The Neretvians were also known as Pagans, because by the time of their Christianization, all Slavs already accepted Christianity. One of their leaders was baptised in Venetia. As soon as the chances were good, the Neretvians would immediately embark on new raids. In 834 and 835, they have cought and killed several Venetian traders returning from Benevent. To punish the Neretvians, the Venetian Doge had launched a military expedition against them in 839. The war went on together with the Dalmatian Croats, but a truce was signed very soon, although, only with the Dalmatian Croats and some of the Pagan tribes. In 840, the Venetians had launched an expedition against the Neretvian Prince Ljudislav, but utterly failed. In 846, a new operation is launched that raided the Slavic land of Pagania, destroying one of her most important cities - Kaorle, although this did not end the Neretvian resistance, as they continued to mercilessly raid and steal from the Venetian occupators.

Neretvia was subjected to Serbian rulers like Petar Gojniković throughought the 9th century. Neretvians then aligned themselves with King Tomislav of Croatia in the first half of the 10th century. After King Trpimir's death, Pagania would eventually be incorporated directly into the Serbian Realm of Prince Časlav of Klonimir from the House of Vlastimir in 927-931. The Serbian period marked Neretvia's Golden Age. In 945 King Krešimir of Croatia died, and Civil War erupted. The Neretvians used Prince Časlav's annexations of Croatian territories and took Kaz, Vis and Lastovo; also managing to defend their own islands of Mljet, Korčula, Brač and Hvar. In 948, Venetian Doge Peter of Crete dispatched 33 Galleys against the Neretvians, but the military attempt ended so drasticly, that since that moment Venetia had to pay taxes regularely to the Neretvian Princes and their supreme rulers.

The Venetian Doge Peter II Orseolo finally crushed them in 998 and assumed the title duke of the Dalmatians (Dux Dalmatianorum), though without prejudice to Byzantine suzerainty. In 1050, the Neretvians agreed to join the Kingdom of Croatia under King Stjepan I. The arisal of Duklja, and its reconstruction of the Serbian realm to the east would bring the occupation of Pagania, and eventual incorporation as a part of Zahumlje.

Zahumlje

Zahumlje got its name from the mountain of Hum near Bona, where the river of Buna comes out. There there were two very old cities: Bona and Hum. Zahumlje's ruling dynasty Višević or Vušević originated from the strims of the river of Visla, somewhere in western White Croatia. They were referred to as Red Croats. Zahumlje decisivly resisted all attempts to be controlled from the Serbian Grand Princes to the north, and eventually its rulers asserted the Grand Princely title themselves. The land of Zahumlje spread eastwards to Kalinovik and the Fields of Gatak, where it bordered with Travunia. The actual border went along the Zachlumian line Popovo-Ljubinje-Dabar and the Byzantine enclave of Dubrovnik. The largest Zachlumoi Cities in Zahumlje were:

Zahumlje was split onto 9 lesser principalities:

Zahumlje was divided into two Duchies: Upper Zahumlje and Lower Zahumlje by the Serbian rulers for easier control. Upper Zahumlje would soon be incorporated directly into Serbia, while lower would continue to exist. Zahumlje would pass through a period of vassalization to King Tomislav of Croatia, become dependent of the reconstructed Serbian realm under Duklja. After numerious dinastiec struggles in the former Serbian lands, before which Zahumlje fully annexed Pagania, Zahumlje would become a direct part of the Grand Principality of Rascia.

Prince Peter of Zahumlje was elected Count of Split.

Travunia

Travunia or Terbounia has been a vassalaged dependent part of Serbia. It was described as part of an entity called Red Croatia. Thus, it was inhabiten by Red Croats or Serbs. In the middle of the 9th century, Grand Prince Vlastimir gave his daughter to marry Prince Krajina of Travunia, giving him full independence. Although, after that, Travunia became a direct part of Serbia. After the Serbian realm of Prince Časlav of Klonimir of Vlastimir crumbled in the second half of the 10th century, Travunia was directly incorporated into Duklja.

Doclea

Duklja was a Slavic medieval state with hereditary lands roughly encompassing the territories of the Zeta River, Skadar Lake and the Boka bay and bordering with Travunia at Kotor. Duklja was at first a semi-independent part of the Grand Principality (Zhupanate) of Rascia (Raška) which was a vassal of the Eastern Roman Empire and later directly under Byzantine suzerainty until it won its independence in the mid-11th century, ruled by the House of Voislav (Vojislavljević). After a large fall, Doclea was incorporated into the unified Serbian state, where it remained until its last remains' falling to Ottoman hands. Its main cities were:

Duklja's capitals were:

Duklja was split into županates:

- Lusca

- Podlugiae

- Gorsca

- Cuceva with Budva

- Cupelnich

- Obliquus

- Prapatna (between today's Bar and Ulcinj)

- Cermenica

- Gripuli

Continental Doclea, or Submontana (Podgoria), which was between the rivers of Rama and Morača, was consisted of:

High Middle Ages

Meanwhile the Croatian kings exacted tribute from the Byzantine cities, Tragurium, Iadera and others, and consolidated their own power in the purely Croatian-settled towns such as Nin, Biograd and Šibenik. The city of Šibenik was founded by Croatian kings. They also ascertained control over the bordering southern duchies. Rulers of the medieval Croatian state who had control over the Dalmatian littoral and the cities were the dukes Trpimir, Domagoj, Branimir, and the kings Tomislav, Trpimir II, Krešimir I, Stjepan Držislav, Petar Krešimir IV and Dmitar Zvonimir.

The Christian schism was an important factor in the history of Dalmatia. While the Croatian-held branch of the Catholic Church in Nin was under Papal jurisdiction, they still used the Slavic liturgy. Both the Latin population of the cities and the Holy See preferred the Latin liturgy, which created tensions between different dioceses. The Croatian population preferred domestic priests, who were married and bearded, and held masses in Croatian language, so they were understood.

The great schism between Eastern and Western Christianity of 1054 further intensified the rift between the coastal cities and the hinterland, with many of the Slavs in the hinterland preferring the Eastern Orthodoxy. Areas of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina also had an indigenous Bosnian Church which was often mistaken for Bogomils.

The Latin influence was increased and the Byzantine practices were further suppressed on the general synods of 1059-1060, 1066, 1075-1076 and on other local synods, notably by demoting the bishopric of Nin, installing the archbishoprics of Spalatum (Split) and Dioclea (Bar), and explicitly forbidding use of any liturgy other than Greek or Latin.

In the period of the rise of the Serbian state of Rascia, the Nemanjić dynasty acquired the southern Dalmatian states by the end of the twelfth century, where the population was mixed Catholic and Orthodox, and founded a Serb Orthodox bishopric of Zahumlje with see in Ston. The Nemanjić Serbia controlled several of the southern coastal cities, notably Kotor and Bar.

Dalmatia never attained a political or racial unity and never formed as a nation, but it achieved a remarkable development of art, science and literature. Politically, the Dalmatian city-states were often isolated and compelled to either fall back on the Venetian Republic for support, or tried to make it on their own.

The geographical position of the Dalmatian city states suffices to explain the relatively small influence exercised by Byzantine culture throughout the six centuries (535-1102) during which Dalmatia was part of the Eastern empire. Towards the close of this period Byzantine rule tended more and more to become merely nominal. The biggest contribution of Byzantine culture in contemporary Croatian culture is the way the name of Jesus is pronounced in standard literary Croatian language - Isus.

The medieval Dalmatia had still included much of the hinterland covered by the old Roman province of Dalmatia - however, the toponym of "Dalmatia" started to shift more towards including only the coastal, Adriatic areas, rather than the mountains inland. By the 15th century, the phrase "Herzegovina" would be introduced, marking the shrink of the borders of Dalmatia to the narrow littoral area.

Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Hungary

As the city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either Venice or Hungary for support. Each of the two political factions had support within the Dalmatian city states, based mostly on economic reasons.

The Venetians, to whom the Dalmatians were already bound by language and culture, could afford to concede liberal terms as its main goal was to prevent the development of any dangerous political or commercial competitor on the eastern Adriatic. The seafaring community in Dalmatia looked to Venice as mistress of the Adriatic. In return for protection, the cities often furnished a contingent to the army or navy of their suzerain, and sometimes paid tribute either in money or in kind. Arbe (Rab), for example, annually paid ten pounds of silk or five pounds of gold to Venice.

Hungary, on the other hand, defeated the last Croat king in 1097 and laid claim on all lands of the Croatian noblemen since the treaty of 1102. King Coloman proceeded to conquer Dalmatia in 1102-1105. The farmers and the merchants who traded in the interior favoured Hungary as their most powerful neighbour on land that affirmed their municipal privileges. Subject to the royal assent they might elect their own chief magistrate, bishop and judges. Their Roman law remained valid. They were even permitted to conclude separate alliances. No alien, not even a Hungarian, could reside in a city where he was unwelcome; and the man who disliked Hungarian dominion could emigrate with all his household and property. In lieu of tribute, the revenue from customs was in some cases shared equally by the king, chief magistrate, bishop and municipality.

These rights and the analogous privileges granted by Venice were, however, too frequently infringed. Hungarian garrisons were being quartered on unwilling towns, while Venice interfered with trade, the appointment of bishops, or the tenure of communal domains. Consequently the Dalmatians remained loyal only while it suited their interests, and insurrections frequently occurred. Even in Zadar four outbreaks are recorded between 1180 and 1345, although Zadar was treated with special consideration by its Venetian masters, who regarded its possession as essential to their maritime ascendancy.

The once rival Romanic and Slavic population eventually started contributing to a common civilization, and Dubrovnik was the primary example of this. By the 13th century, the councilmen from Dubrovnik names were mixed, and in the 15th century the literature was largely written in the Slavic language (from which Croatian language is directly descended), and the city was often called by its Slavic name, Dubrovnik.

The doubtful allegiance of the Dalmatians tended to protract the struggle between Venice and Hungary, which was further complicated by internal discord due largely to the spread of the Bogomil heresy, and by many outside influences.

The cities of Zadar, Split, Trogir and Dubrovnik and the surrounding territories each changed hands several times between Venice, Hungary and the Byzantium during the 12th century.

In 1202, the armies of the Fourth Crusade rendered assistance to Venice by occupying Zadar for it. In 1204 the same army conquered Byzantium and finally eliminated the Eastern Empire from the list of contenders on Dalmatian territory.

The early 13th century was marked by a decline in external hostilities. The Dalmatian cities started accepting foreign sovereignty (mainly of Venice) but eventually they reverted to their previous desire for independence. The Mongol invasion severely impaired Hungary, so much that in 1241, the king Bela IV had to take refuge in Dalmatia (in the Klis fortress). The Mongols attacked the Dalmatian cities for the next few years but eventually withdrew.

The Croats were no longer regarded by the city folk as a hostile people, in fact the power of certain Croatian magnates, notably the counts Šubić of Bribir, was from time to time supreme in the northern districts (in the period between 1295 and 1328).

In 1346, Dalmatia was struck by the Black Death. The economic situation was also poor, and the cities became more and more dependent on Venice.

Stephen Tvrtko, the founder of the Bosnian kingdom, was able in 1389 to annex the Adriatic littoral between Kotor and Šibenik, and even claimed control over the northern coast up to Rijeka except for the Venetian-ruled Zara (Zadar), and his own independent ally, Dubrovnik. This was only temporary, as the Hungarians and the Venetians continued their struggle over Dalmatia as soon as Tvrtko died in 1391.

An internal struggle of Hungary, between king Sigismund and the Neapolitan house of Anjou, also reflected on Dalmatia: in the early 15th century, all Dalmatian cities welcomed the Neapolitan fleet except for Dubrovnik. The Bosnian duke Hrvoje controlled Dalmatia for the Angevins, but later switched loyalty to Sigismund.

Over the period of twenty years, this struggle weakened the Hungarian influence. In 1409, Ladislaus of Naples sold his rights over Dalmatia to Venice for 100,000 Ducats. Venice gradually took over most of Dalmatia by 1420. In 1437, Sigismund recognized Venetian rule over Dalmatia in return for 100,000 Ducats. The city of Omiš yielded to Venice in 1444, and only Dubrovnik preserved its freedom.

Ottoman and Venetian rule

During the Venetian rule in Dalmatia from 1420 to 1797 the number of Orthodox Serbs in Dalmatia was increased by numerous migrations

An interval of peace ensued, but meanwhile the Ottoman advance continued.

Hungary was itself assailed by the Turks, and could no longer afford to try to control Dalmatia. Christian kingdoms and regions in the east fell one by one, Constantinople in 1453, Serbia in 1459, neighbouring Bosnia in 1463, and Herzegovina in 1483. Thus the Venetian and Ottoman frontiers met and border wars were incessant.

Dubrovnik sought safety in friendship with the invaders, and in one particular instance, actually sold two small strips of its territory (Neum and Sutorina) to the Ottomans in order to prevent land access from the Venetian territory.

In 1508 the hostile League of Cambrai compelled Venice to withdraw its garrison for home service, and after the overthrow of Hungary in 1526 the Turks were able easily to conquer the greater part of Dalmatia by 1537. The peace of 1540 left only the maritime cities to Venice, the interior forming a Turkish province, governed from the fortress of Klis by a Sanjakbeg (an administrator with military powers).

Christian Croats from the neighbouring lands now thronged to the towns, outnumbering the Romanic population even more, and making their language the primary one. The pirate community of the "uskoks" had originally been a band of these fugitives, esp. near Senia; its exploits contributed to a renewal of war between Venice and Turkey (1571-1573). An extremely curious picture of contemporary manners is presented by the Venetian agents, whose reports on this war resemble some knightly chronicle of the Middle Ages, full of single combats, tournaments and other chivalrous adventures. They also show clearly that the Dalmatian levies far surpassed the Italian mercenaries in skill and courage. Many of these troops served abroad; at the Battle of Lepanto, for example, in 1571, a Dalmatian squadron assisted the allied fleets of Spain, Venice, Austria and the Papal States to crush the Turkish navy.

The continental bits of Dalmatia were under Ottoman rule, parts of the Viyalet of Bosnia or the Klis Sanjak. The desolated areas of the Knin Frontier and Bukovica were inhabited by Orthodox Serbs from Bosnia, while Boka received constant Serb migrations from Herzegovina and Montenegro. The Serbs formed one quarter of Dalmatia's population in the 16th century. They had absolute majority in the Knin Frontier, Bukovica and Boka. The Ottomans have resettled this populace to create a living defence towards the territories of the Venetian Republic. A great portion of this population fled to Venetian land and gladly fought against the Ottomans. The number of Serbs in Venetian Dalmatia rapidly increased during the War of Crete in 1645 - 1669 and yhe Great Viennese War war in 1683 - 1699, after which peace of Karlowitz gave the whole of Dalmatia to Ston and from Sutorina to Boka kotorska to the Venetian Republic. After the Venetian-Turkish war of 1714-1718, Venetian territorial gains were confirmed by the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz. The number of Dalmatian Serbs remained between 20% and 25% by the end of Venetian rule.

The Serbian peasant population of infertile Upper Dalmatia was freed of Feudal bounds, according that they fight wars for the Venetian Republic. The Serbs living in Urban cities of Dalmatia were much wealthier. The Serbs in Dalmatia with Boka have had strong national and religious determination through numerous old monasteries as beacons of culture and faith. Such were the early 14th century Krupa, Krka and Dragović monasteries in the Knin Frontier and Bukovica. The Serbs in Boka kotorska had much more cultural advancement due to the nearby Cetinje Metropolitan and the Venetians had to fall back from influencing the religious life of people there.

Dalmatia was the largest Europe's concentration of Roman Catholic Christian Bishops, Priesthood, Churches, Monasteries and religious institutions. The Catholic Bishops controlled the Orthodox Episcopy in Dalmatia by naming the Eastern Othodox Christian Episcopes themselves.

Dalmatia experienced a period of intense economic and cultural growth in the 18th century, given how trade routes with the hinterland were reestablished in peace. Christians that noticeably migrated from the Ottoman-held territory into the Dalmatian cities converted from Orthodoxy to Catholicism.

Because the Venetians were able to reclaim some of the inland territories in the north during the Turkish wars, the region of Dalmatia was no longer restricted to the coastline and the islands. However, the Venetian influence wasn't as strong in the former southern Dalmatia, meaning that the toponym did not extend inland into areas of Herzegovina or Montenegro.

This period was abruptly interrupted with the fall of the Venetian republic in 1797.

Modern Era

Dalmatia in the Napoleonic Era

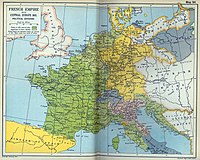

Later in 1797, in the treaty of Campo Formio, Napoleon gave Dalmatia to Austria in return for Belgium. The republics of Dubrovnik and Poljica retained their independence, and Dubrovnik grew rich by its neutrality during the earlier Napoleonic wars.

By the peace of Pressburg in 1805, Istria, Dalmatia and the Bay of Kotor were handed over to France as the Illyrian provinces. In 1806, the Republic of Dubrovnik finally succumbed to foreign (French) troops under general Marmont, the same year a Montenegrin force supported by the Russians tried to contest the French by seizing Boka Kotorska. The allied forces have pushed the French to Dubrovnik. The Russians induced the Montenegrins to render aid and they proceeded to take the islands of Korčula and Brač but made no further progress, and withdrew in 1807 under the treaty of Tilsit. The Republic of Dubrovnik was officially annexed to the Illyrian Provinces in 1808.

The major part of the Dalmatian population was Roman Catholic Christian.

In 1809, war again broke out between France and Austria. In the summer, Austrian forces retook Dalmatia, but this lasted only until the Treaty of Schönbrunn in the autumn of the same year. Austria-Hungary declared war on France in 1813, restored control over Dalmatia by 1815 and formed a temporary Kingdom of Illyria. In 1822, this was eliminated and Dalmatia was placed under Austrian administration.

Habsburg Austrian rule (Age of nationalism)

After the revolutions of 1848 and particularly since the 1860s, in the age of romantic nationalism, two factions appeared.

The first was the pro-Croatian or unionist one, led by People's party (Narodna stranka) and Croatian rights' party (Hrvatska stranka prava), which advocated for a union of Dalmatia with the remaining part of Croatia that was under Hungarian administration.

The second was the autonomist one, which first advocated a Dalmatian nationality but idea found no ground, so they turned towards the idea of Italianhood and a possible union with the emerging Kingdom of Italy. The 1880 census gives following data for Dalmatia: 371,565 Croats, 78,714 Serbs and 27,305 Italians. The Croatian faction won the elections in Dalmatia in 1870, but they couldn't go through with the merger with Croatia due to Austrian intervention.

The political alliances in Dalmatia shifted over time. At the beginning, the unionists and autonomists were allied together, against centralism of Vienna. After a while, when the national question came to prominence, they split. A third splintering happened when the local Orthodox population, few of whom were nationally conscious Serbs, heard of the ideas of unification of all Serbs through of the Serbian Orthodox Church, which acted as Serbia's agit-prop agency abroad. As a result, Serbized Orthodox population started to side with the autonomists and irredentists rather than the unionists.

20th Century

First half of the 20th century

In World War I, Austria-Hungary was defeated and it disintegrated, which helped solve the internal political conflict in Dalmatia.

Under the Treaty of London of 1915, Italy was to attain the northern Dalmatia (including cities of Zadar, Šibenik and Knin), but it occupied even more of it. After the war, Dalmatia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and after negotiations, only Zadar and the island of Lastovo remained part of Italy.

When the Croatian Banate was in 1939 formed, the biggest part of Dalmatia was in it.

In April 1941, during World War II, Axis powers invaded and conquered Yugoslavia. A month later, large sections of Dalmatia were annexed by Italy, the rest being formally left to Independent State of Croatia but in reality occupied by Italian forces which later supported Chetniks in Serb-populated areas. This intolerable situation led many Croats from Dalmatia to join resistance movement led by Tito's Partisans.

In September 1943, following the capitulation of Italy, large sections of Dalmatia were liberated by Partisans, only to be reoccupied, this time by Wehrmacht. Still, Tito's partisans were faster in disarming the Italians, that way acquiring a large amount of light and heavy weapons which in turn made them a much stronger opponent. Still, in later stages of war, many Dalmatian Croats went in exile, in fear from Third Reich's vindictive actions, especially after strong rumours that a second front would be formed and that there would be an invasion on the Croatian coast. In the second of half of 1944, Partisans, supplied by the Allies, finally liberated Dalmatia.

After 1945, most of the remaining Italians fled the region. They were treated as remnants of the occupation force and were given an option to leave for Italy. Some died in the so-called foibe massacres, although this was more common in Istria and elsewhere than in Dalmatia.

After the World War II, Dalmatia was divided between three republics of socialist Yugoslavia - almost all of the territory went to Croatia, leaving Boka Kotorska to Montenegro and small strip of coast at Neum to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Dalmatia in independent Croatia

- For a complete account of the War of Independence, see the Croatian War of Independence

In 1991, when Yugoslavia began to disintegrate, Croatia declared independence. The Homeland war (Domovinski rat) affected sections of northern Dalmatia, where there lived a significant population of Serbs. They rebelled, under encouragement and with assistance from a variety of Serbian nationalist circles, and seceded into the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The center of the RSK was in the northern Dalmatian town of Knin.

The establishment of the RSK was helped by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), as well as paramilitary troops that came from Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. The Serbian forces had a prevalence in equipment and munitions because of JNA support, and they proceeded to commit various acts of terrorism, including shelling attacks on civilian targets.

The Yugoslav People's Army operated from their barracks, that were mostly positioned in bigger cities and stategically important points. In some bigger cities JNA had built large residential blocs, and in the opening stages of the war it was believed that those buildings will be used by sharpshooters or for reconnaisanse purposes. This widespread belief, although justified in few cases, served mostly as an excuse for various Croatian paramilitary and vigilante groups to forcibly evict members of JNA families from their homes, rob their property and sometimes even subject them to torture, rape and murder.

First attempts to take over JNA facilities occurred in August in Sinj and failed, but the major action took place in September 1991. Croatian Army and police were then more successful, although most of the objects taken were repair shops, warehouses and similar facilities, either poorly defended or commanded by officers sympathetic to Croatian cause. Major bases, commanded by die-hard officers and manned by reservists from Montenegro and Serbia, became the object of standoffs that usually ended with JNA personnel and equipment being evacuated under supervision of EEC observers. This process was completred shortly after Sarajevo armistice in January 1992.

All non-Serb population was ethnically cleansed from controlled areas, notably the villages of Škabrnja and Kijevo. Croatian refugees, tens of thousands of them, found shelter in many of the Dalmatian coastal towns where they were placed in empty tourist facilities.

In 1991, the Dalmatian Serb pogrom of May 1991 happened, in which up to 350 Serb housing, most notably in Zadar and Trogir was destroyed by the Croatian forces.

By early 1992, the military positions were mostly entrenched, and further expansion of the RSK was stopped. The Serbian forces continued terrorist actions by way of random shelling of Croatian cities, and this continued occasionally over the next four years.

Besides the northern hinterland that bordered with Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Yugoslav People's Army also occupied sections of southern Dalmatia around Dubrovnik, as well as the islands of Vis and Lastovo. These lasted until 1992.

The United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed throughout the UNPA zones, including those in northern Dalmatia, as well as on Prevlaka.

The Croatian government gradually restored control over all of Dalmatia, in the following military operations:

- September 1991: September War - successful defence of Šibenik from JNA onslaught and takeover of JNA bases in the area.

- May and July 1992: Operation Tigar, JNA was forced to retreat from Vis, Lastovo, Mljet and areas around Dubrovnik.

- July 1992: Miljevci Heights in Šibenik hinterland, near Drniš, were liberated

- January 1993: Operation Maslenica, Croatian forces liberated Zadar and Biograd hinterland.

- In August 1995 Croatian forces conducted Operation Storm, ending Krajina and restoring Croatian sovereignty to international recognised borders.

During Operation Storm majority of Serb population from Krajina has left their homes, while minority of those who stayed - mostly elderly people - were occasionally subjected to acts of murder. Homes left by ethnic Serbs were taken over by ethnic Croatian refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina with the help and encouragement of Croatian authorities. Through the past decade, number of ethnic Serb refugees have returned and gradually reverted demographic results of war in certain areas, although it is very unlikely that their proportion in region's population will ever reach pre-war level.

Dalmatia has arguably suffered in war more than other Croatian regions, with its infrastructure ruined, while tourism industry - previously the most important source of income - was deeply affected by negative publicity and didn't properly recover until late 1990s. Dalmatian population in general suffered dramatic drop in living standard which created chasm between Dalmatia and relatively more prosperous northern sections of Croatia. This chasm reflected in extreme nationalism enjoying visibly higher levels of support in Dalmatia than in the rest of Croatia, which embraced more moderate course.

This phenomenon manifested not only in Dalmatia being reliable stronghold for HDZ and other Croatian right-wing parties, but also in mass protests against Croatian Army generals being prosecuted for war crimes. Indictment and against General Mirko Norac in early 2001 drew 150,000 people to the streets of Split - which is arguably the largest protest in the history of modern Croatia.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- RSK, Vrhovni savjet odbrane, Knin, 4. avgust 1995., 16.45 časova, Broj 2-3113-1/95. The faximile of this document was published in: Rade Bulat "Srbi nepoželjni u Hrvatskoj", Naš glas (Zagreb), br. 8.-9., septembar 1995., p. 90.-96. (the faximile is on the page 93.).

Vrhovni savjet odbrane RSK (The Supreme Council of Defense of Republic of Serb Krajina) brought a decision 4. August 1995 in 16.45. This decision was signed by Milan Martić and later verified in Glavni štab SVK (Headquarters of Republic of Serb Krajina Army) in 17.20.

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-82/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

This is the document of Republic headquarters of Civil Protection of RSK. In this document it was ordered to all subordinated headquarters of RSK to immediately give all reports about preparations for the evacuation, sheltering and taking care of evacuated civilians ("evakuacija, sklanjanje i zbrinjavanje") (the deadline for the report was 3. August 1995 in 19 h).

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-83/95., Knin, 02.08.1995., Pripreme za evakuaciju materijalnih, kulturnih i drugih dobara (The preparations for the evacuation of material, cultural and other goods), HDA, Dokumentacija RSK, kut. 265

This was the next order from the Republican HQ of Civil Protection. It was referred to all Municipal Headquarters of Civil Protection. In that document was ordered to all subordinated HQ's to implement the preparation of evacuation of all material and all mobile cultural goods, archives, evidentions and materials that are highly confidential/top secret, money, lists of valuable stuff (?)("vrednosni popisi") and referring documentations.

- Drago Kovačević, "Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu" , Beograd 2003. , p. 93.-94.

- Milisav Sekulić, "Knin je pao u Beogradu" , Bad Vilbel 2001., p. 171.-246., p. 179.

- Marko Vrcelj, "Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991-95" , Beograd 2002., p. 212.-222.

External links

- WHKMLA History of Dalmatia

- The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia articles on Dalmatia: