| Revision as of 21:18, 14 November 2006 view source81.157.77.93 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:19, 14 November 2006 view source 81.157.77.93 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| I think a dork wrote this cos its really patronising to people with the schizophrenia |

I think a dork wrote this cos its really patronising to people with the schizophrenia and does nothing for me apart from make me wanna get totally lashed tonight. | ||

| Wah hey. | |||

| Western psychiatric medicine tends to favor a definition of symptoms that depends on form rather than content (an innovation first argued for by psychiatrists ] and ]). Therefore, a subject should be able to believe anything, however unusual or socially unacceptable, without being diagnosed delusional, unless their belief is held in a particular way. In principle, this would stop people being forcibly detained or treated simply for what they believe. However, the distinction between form and content is not easy, or always possible, to make in practice (see ]). This had led to accusations by ], ] and mental health system survivor groups that psychiatric abuses exist in the West as well. | |||

| ====Genetic==== | ====Genetic==== | ||

Revision as of 21:19, 14 November 2006

I think a dork wrote this cos its really patronising to people with the schizophrenia and does nothing for me apart from make me wanna get totally lashed tonight.

Wah hey.

Western psychiatric medicine tends to favor a definition of symptoms that depends on form rather than content (an innovation first argued for by psychiatrists Karl Jaspers and Kurt Schneider). Therefore, a subject should be able to believe anything, however unusual or socially unacceptable, without being diagnosed delusional, unless their belief is held in a particular way. In principle, this would stop people being forcibly detained or treated simply for what they believe. However, the distinction between form and content is not easy, or always possible, to make in practice (see delusion). This had led to accusations by anti-psychiatry, surrealist and mental health system survivor groups that psychiatric abuses exist in the West as well.

Genetic

Substantial evidence suggests that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has a heritable component (some estimates are as high as 80%). Current research suggests that environmental factors play a significant role in the expression of any genetic disposition towards schizophrenia (i.e. if someone has the genes that increase risk, this will not automatically result in a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life). A recent review of the genetic evidence has suggested a more than 28% chance of one identical twin obtaining the diagnosis if the other already has it (see twin studies), but such studies are not noted for pondering the likelihood of similarities of social class and/or other socio-psychological factors between the twins. The estimates of heritability of schizophrenia from twin studies varies a great deal, with some notable studies showing rates as low as 11.0%–13.8% among monozygotic twins, and 1.8%–4.1% among dizygotic twins. However, Jay Joseph and a vocal lobby of psychiatrists and scientists who are at present in the minority have taken to task the twin studies, and have argued that the genetic basis of schizophrenia is open to question.

There is currently a great deal of effort being put into molecular genetic studies of schizophrenia, which attempt to identify specific genes which may increase risk. Because of this, the genes that are thought to be most involved can change as new evidence is gathered. A 2003 review of linkage studies listed seven genes as likely to increase risk for a later diagnosis of the disorder. Two more recent reviews have suggested that the evidence is currently strongest for two genes known as dysbindin (DTNBP1) and neuregulin (NRG1), with a number of other genes (such as COMT, RGS4, PPP3CC, ZDHHC8, DISC1, and AKT1) showing some early promising results that have not yet been fully replicated.

Environmental

Considerable evidence indicates that stressful life events cause or trigger schizophrenia. Childhood experiences of abuse or trauma have also been implicated as risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life.

Evidence is also consistent that negative attitudes towards individuals with (or with a risk of developing) schizophrenia can have a significant adverse impact. In particular, critical comments, hostility, authoritarian and intrusive or controlling attitudes (termed 'high expressed emotion' by researchers) from family members have been found to correlate with a higher risk of relapse in schizophrenia across cultures. It is not clear whether such attitudes play a causal role in the onset of schizophrenia, although those diagnosed in this way may claim it to be the primary causal factor. The research has focused on family members but also appears to relate to professional staff in regular contact with clients. While initial work addressed those diagnosed as schizophrenic, these attitudes have also been found to play a significant role in other mental health problems. This approach does not blame 'bad parenting' or staffing, but addresses the attitudes, behaviors and interactions of all parties. Some go as far as to criticise the whole approach of seeking to localise 'mental illness' within one individual - the patient - rather than his/her group and its functionality, citing a scapegoat effect.

Factors such as poverty and discrimination also appear to be involved in increasing the risk of schizophrenia or schizophrenia relapse, perhaps due to the high levels of stress they engender, or faults in diagnostic procedure/assumptions. Racism in society, including in diagnostic practices, and/or the stress of living in a different culture, may explain why minority communities have shown higher rates of schizophrenia than members of the same ethnic groups resident in their home country. The "social drift hypothesis" suggests that the functional problems related to schizophrenia, or the stigma and prejudice attached to them, can result in more limited employment and financial opportunities, so that the causal pathway goes from mental health problems to poverty, rather than, or in addition to, the other direction. Some argue that unemployment and the long-term unemployed and homeless are simply being stigmatised.

One particularly stable and replicable finding has been the association between living in an urban environment and schizophrenia diagnosis, even after factors such as drug use, ethnic group and size of social group have been controlled for. A recent study of 4.4 million men and women in Sweden found an alleged 68%–77% increased risk of diagnosed psychosis for people living in the most urbanized environments, a significant proportion of which is likely to be described as schizophrenia.

One curious finding is that people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring (at least in the northern hemisphere). However, the effect is not large. Some researchers postulate that the correlation is due to viral infections during the third trimester (4-6 months) of pregnancy.

A study by Sweden's Karolinska Institute and Bristol University in the UK, looked at the medical records of over 700,000 people and calculated that 15.5% of cases of schizophrenia seen in the group may have been due to the patient having a father who was aged over 30 years at their birth, the researchers argue this is due to build up of mutations in the sperm of elder fathers.

Neurobiological influences

Early neurodevelopment

It is also thought that processes in early neurodevelopment are important, particularly during pregnancy. For example, women who were pregnant during the Dutch famine of 1944, where many people were close to starvation, had a higher chance of having a child who would later develop schizophrenia. Similarly, studies of Finnish mothers who were pregnant when they found out that their husbands had been killed during the Winter War of 1939–1940 have shown that their children were much more likely to develop schizophrenia when compared with mothers who found out about their husbands' death after pregnancy, suggesting that even psychological trauma in the mother may have an effect. Furthermore, there is now significant evidence that prenatal exposure to infections increases the risk for developing schizophrenia later in life, providing additional evidence for a link between developmental pathology and risk of developing the condition.

Some researchers have proposed that environmental influences during childhood also interact with neurobiological risk factors to influence the likelihood of developing schizophrenia later in life. The neurological development of children is considered sensitive to features of dysfunctional social settings, such as trauma, violence, lack of warmth in personal relationships and hostility. These have all been found to be risk factors for the later development of schizophrenia. Research has suggested that effects of the childhood environment, favorable or unfavorable, interact with genetics and the processes of neurodevelopment, with long-term consequences for brain function. Consequently, this is thought to influence the underlying vulnerability for psychosis later in life, particularly during the adult years.

Role of dopamine

In adult life, particular importance has been placed upon the function (or malfunction) of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway in the brain. This theory, known as the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, reduced psychotic symptoms. These drugs have now been developed further and antipsychotic medication is commonly used as a first line treatment.

However, this theory is now thought to be overly simplistic as a complete explanation, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) is equally effective as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect. Psychiatrist David Healy has also argued that pharmaceutical companies have promoted certain oversimplified biological theories of mental illness to promote their own sales of biological treatments.

Role of glutamate and the NMDA receptor

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in the development of schizophrenia. This theory has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition. The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia as an increasingly popular explanation. Further support of this theory has come from trials showing the efficacy of molecules, which are coagonists at the NMDA receptor complex, in reducing schizophrenic symptoms. The precursors D-serine, glycine, and D-cycloserine all enhance NMDA function through the glycine co-agonist site. Several placebo controlled trials have shown a reduction mainly in negative symptoms with high dose therapy. Currently type 1 glycine transporter inhibitors are in late-state preclinical for the treatment of schizophrenia. They increase glycine concentrations in the brain thus causing increased NMDA receptor activation and a reduction in symptoms.

Anatomy and physiology of the brain

Much recent research has focused on differences in structure or function in certain brain areas in people diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Early evidence for differences in the neural structure came from the discovery of ventricular enlargement in people diagnosed with schizophrenia, for whom negative symptoms were most prominent. However, this finding has not proved particularly reliable on the level of the individual person, with considerable variation between patients. A letter to the editor of the American Journal of Psychiatry links ventricular enlargement with exposure to antipsychotic drugs.

More recent studies have shown a large number of differences in brain structure between people with and without diagnoses of schizophrenia. However, as with earlier studies, many of these differences are only reliably detected when comparing groups of people, and are unlikely to predict any differences in brain structure of an individual person with schizophrenia.

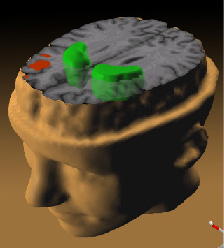

Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus, and temporal lobes. These differences are heavily linked to the neurocognitive deficits which often occur with schizophrenia, particularly in areas of memory, attention, problem solving, executive function and social cognition.

Electroencephalograph (EEG) recordings of persons with schizophrenia performing perception oriented tasks showed an absence of gamma band activity in the brain, indicating weak integration of critical neural networks in the brain. Those who experienced intense hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thinking showed the lowest frequency synchronization. None of the drugs taken by the persons scanned had moved neural synchrony back into the gamma frequency range. Gamma band and working memory alterations may be related to alterations in interneurons that produced the neurotransmitter GABA. Alterations in a subclass of GABAergic interneurons which produce the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin have been shown to exist in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia.

Incidence and prevalence

In the western world, schizophrenia is typically diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood. In the western world, it is found approximately equally in men and women, though the onset tends to be later in women, who also tend to have a better course and outcome. Although rare, there are also instances of childhood onset schizophrenia and late-onset schizophrenia that occurs in the elderly.

The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is commonly given at 1%; however, a recent review of studies from around the world estimated it to be 0.55%. The same study also found that prevalence may vary greatly from country to country, despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at the same rate throughout the world. It is worth noting however, that this may be in part due to differences in the way schizophrenia is diagnosed. The incidence of schizophrenia was given as a range of between 7.5 and 16.3 cases per year per 100,000 population.

Schizophrenia is also a major cause of disability. In a recent 14-country study, active psychosis was ranked the third most disabling condition after quadriplegia and dementia and before paraplegia and blindness.

Treatment

Medication and hospitalization

Currently schizophrenia has not been cured although many psychiatrists and psychologists believe that it can be managed. The first line pharmacological therapy for schizophrenia is usually the use of antipsychotic medication . The concept of 'curing' schizophrenia is controversial as there are no clear criteria for what might constitute a cure, although some criteria for the remission of symptoms have recently been suggested. Therefore, antipsychotic drugs are only thought to provide symptomatic relief from the positive symptoms of psychosis. The newer atypical antipsychotic medications (such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, and amisulpride) are usually preferred over older typical antipsychotic medications (such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol) due to their favorable side-effect profile. Compared to the typical antipsychotics, the atypicals are associated with a lower incident rate of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia (TD) although they are more likely to induce weight gain and so increase risk for obesity-related diseases. It is still unclear whether newer drugs reduce the chances of developing the rare but potentially life-threatening neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). While the atypical antipsychotics are associated with less EPS and TD than the conventional antipsychotics, some of the agents in this class (especially olanzapine and clozapine) appear to be associated with metabolic side effects such as weight gain, hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia that must be considered when choosing appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Atypical and typical antipsychotics are generally thought to be equivalent for the treatment of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. It has been suggested by some researchers that the atypicals have some beneficial effects on negative symptoms and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, although the clinical significance of these effects has yet to be established. However, recent reviews have suggested that typical antipsychotics, when dosed conservatively, may have similar effects to atypicals. The atypical antipsychotics are much more costly as they are still within patent, whereas the older drugs are available in inexpensive generic forms. Aripiprazole is a drug from a new class of antipsychotic drugs (variously named 'dopamine system stabilizers' or 'partial dopamine agonists') that have recently been developed and is now widely licensed to treat schizophrenia.

The efficacy of schizophrenia treatment is often assessed by using standardized assessment methods, one of the most common being the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS).

Hospitalization may occur with severe episodes. This can be voluntary or (if mental health legislation allows it) involuntary (called civil or involuntary commitment). Mental health legislation may also allow people to be treated against their will. However, in many countries such legislation does not exist, or does not have the power to enforce involuntary hospitalization or treatment.

Therapy and community support

Psychotherapy or other forms of talk therapy may be offered, with cognitive behavioral therapy being the most frequently used. This may focus on the direct reduction of the symptoms, or on related aspects, such as issues of self-esteem, social functioning, and insight. Although the results of early trials with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were inconclusive, more recent reviews suggest that CBT can be an effective treatment for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia.

A relatively new approach has been the use of cognitive remediation therapy, a technique aimed at remediating the neurocognitive deficits sometimes present in schizophrenia. Based on techniques of neuropsychological rehabilitation, early evidence has shown it to be cognitively effective, with some improvements related to measurable changes in brain activation as measured by fMRI.

Electroconvulsive therapy (also known as ECT or 'electroshock therapy') may be used in countries where it is legal. It is not considered a first line treatment but may be prescribed in cases where other treatments have failed. Psychosurgery has now become a rare procedure and is not a recommended treatment for schizophrenia.

Other support services may also be available, such as drop-in centers, visits from members of a 'community mental health team' or assertive community treatment team, and patient-led support groups. In recent years the importance of service-user led recovery based movements has grown substantially throughout Europe and America. Groups such as the Hearing Voices Network and more recently, the Paranoia Network, have developed a self-help approach that aims to provide support and assistance outside of the traditional medical model adopted by mainstream psychiatry. By avoiding framing personal experience in terms of criteria for mental illness or mental health, they aim to destigmatize the experience and encourage individual responsibility and a positive self-image.

In many non-Western societies, schizophrenia may be treated with more informal, community-led methods. A particularly sobering thought for Western psychiatry is that the outcome for people diagnosed with schizophrenia in non-Western countries may actually be much better than for people in the West. The reasons for this recently discovered fact are still far from clear, although cross-cultural studies are being conducted to find out why.

A recent randomised controlled trial found that music therapy significantly improved symptom scores in a group of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. A notable early mention of the beneficial effect of music on mental illness was in 1621 by Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Dietary supplements

Omega-3 fatty acids (found naturally in foods such as oily fish, flax seeds, hemp seeds, walnuts and canola oil) have recently been studied as a treatment for schizophrenia. Although the number of research trials has been limited, the majority of randomized controlled trials have found omega-3 supplements to be effective when used as a dietary supplement.

Prognosis

Prognosis for any particular individual affected by schizophrenia is particularly hard to judge as treatment and access to treatment is continually changing, as new methods become available and medical recommendations change.

One retrospective study has shown that about a third of people make a full recovery, about a third show improvement but not a full recovery, and a third remain ill. A more recent study using stricter recovery criteria (i.e. concurrent remission of positive and negative symptoms and specific instances of adequate social / vocational functioning) reported a recovery rate of 13.7%.

The exact definition of what constitutes a recovery has not been widely defined, however, although criteria have recently been suggested to define a remission in symptoms. Therefore, this makes it difficult to give an exact estimate as recovery and remission rates are not always comparable across studies.

The World Health Organization conducted two long-term follow-up studies involving more than 2,000 people suffering from schizophrenia in different countries. These studies findings were that these patients have much better long-term outcomes in poor countries (India, Colombia and Nigeria) than in rich countries (USA, UK, Ireland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Japan, and Russia), despite the fact antipsychotic drugs are typically not widely available in poorer countries, thus raising questions about the effectiveness such drug-based treatments.

Prognosis also depends on some other factors. Females tend to show recovery rates higher than males, and acute and sudden onset of schizophrenia is associated with higher rates of recovery, while gradual onset is associated with lower rates. Most studies done on this subject, however, are correlational in nature, and a clear cause-and-effect relationship is difficult to establish. Pre-morbid functioning and positive prognosis also seem to be correlated.

In a study of over 168,000 Swedish citizens undergoing psychiatric treatment, schizophrenia was associated with an average life expectancy of approximately 80-85% of that of the general population. Women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were found to have a slightly better life expectancy than that of men, and as a whole, a diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a better life expectancy than substance abuse, personality disorder, heart attack and stroke.

There is an extremely high suicide rate associated with schizophrenia. A recent study showed that 30% of patients diagnosed with this condition had attempted suicide at least once during their lifetime. Another study suggested that 10% of persons with schizophrenia die by suicide.

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Just as the diagnosis itself is mired in controversy and counter-accusation, it is difficult to establish a clear picture of recovery and rehabilitation. Both long ago and in the recent past, patients in developed countries were told that chances of recovery were limited, with statistics being quoted to support this negative prognosis. Today, with the advent of a vocal Recovery Movement in mental health, statistics are quoted in a conflicting fashion, and attention is drawn to cultural and local factors in impeding or accelerating recovery. Rehabilitation provision is uneven and strongly dependent on local political culture and/or resources.

Schizophrenia and drug use

The relationship between schizophrenia and drug use is complex, meaning that a clear causal connection between drug use and schizophrenia has been difficult to tease apart. There is strong evidence that using certain drugs can trigger either the onset or relapse of schizophrenia in some people. It may also be the case, however, that people with schizophrenia use drugs to overcome negative feelings associated with both the commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication and the condition itself, where negative emotion, paranoia and anhedonia are all considered to be core features.

The rate of substance use is known to be particularly high in this group. In a recent study, 60% of people with schizophrenia were found to use substances and 37% would be diagnosable with a substance use disorder.

Amphetamines

As amphetamines are believed to elevate dopamine production, and that an excess of dopamine is responsible for schizophrenia (known as the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia) the amphetamines may worsen schizophrenia symptoms.

Hallucinogens

Schizophrenia can sometimes be triggered by heavy use of hallucinogenic drugs, although some claim that a predisposition towards developing schizophrenia is needed for this to occur. There is also some evidence suggesting that people suffering schizophrenia but responding to treatment can have relapse because of subsequent drug use. Some widely known cases where hallucinogens have been suspected of precipitating schizophrenia are Pink Floyd founder-member Syd Barrett and Beach Boys songwriter Brian Wilson.

Drugs such as ketamine, PCP, and LSD have been used to mimic schizophrenia for research purposes, although this has now fallen out of favor with the scientific research community, as the differences between the drug induced states and the typical presentation of schizophrenia have become clear.

Hallucinogenic drugs were also briefly tested as possible treatments for schizophrenia by psychiatrists such as Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer in the 1950s. It was mainly for this experimental treatment of schizophrenia that LSD administration was legal, briefly before its use as a recreational drug led to its criminalization.

Cannabis

There is evidence that cannabis use can contribute to schizophrenia. Some studies suggest that cannabis is neither a sufficient nor necessary factor in developing schizophrenia, but that cannabis may significantly increase the risk of developing schizophrenia and may be, among other things, a significant causal factor. Nevertheless, some previous research in this area has been criticised as it has often not been clear whether cannabis use is a cause or effect of schizophrenia. To address this issue, a recent review of studies from which a causal contribution to schizophrenia can be assessed has suggested that cannabis statistically doubles the risk of developing schizophrenia on the individual level, and may, assuming a causal relationship, be responsible for up to 8% of cases in the population.

Tobacco

It has been noted that the majority of people with schizophrenia (estimated between 75% and 90%) smoke tobacco. However, people diagnosed with schizophrenia have a much lower than average chance of developing and dying from lung cancer. While the reason for this is unknown, it may be because of a genetic resistance to the cancer, a side-effect of drugs being taken, or a statistical effect of increased likelihood of dying from causes other than lung cancer.

It is argued that the increased level of smoking in schizophrenia may be due to a desire to self-medicate with nicotine. A recent study of over 50,000 Swedish conscripts found that there was a small but significant protective effect of smoking cigarettes on the risk of developing schizophrenia later in life. While the authors of the study stressed that the risks of smoking far outweigh these minor benefits, this study provides further evidence for the 'self-medication' theory of smoking in schizophrenia and may give clues as to how schizophrenia might develop at the molecular level. Furthermore, many people with schizophrenia have smoked tobacco products long before they are diagnosed with the illness, and some groups advocate that the chemicals in tobacco have actually contributed to the onset of the illness and have no benefit of any kind.

It is of interest that cigarette smoking affects liver function such that the antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia are broken down in the blood stream more quickly. This means that smokers with schizophrenia need slightly higher doses of antipsychotic drugs in order for them to be effective than do their non-smoking counterparts.

Schizophrenia and violence

Violence perpetrated by people with schizophrenia

Although schizophrenia is sometimes associated with violence in the media only a small minority of people with schizophrenia become violent, and only a minority of people who commit criminal violence have been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Research has suggested that schizophrenia is associated with a slight increase in risk of violence, although this risk is largely due to a small sub-group of individuals for whom violence is associated with concurrent substance abuse and ceasing psychiatric drugs. For the most serious acts of violence, long-term independent studies of convicted murderers in both New Zealand and Sweden found that 3.7%–8.9% had been given a previous diagnosis of schizophrenia.

There is some evidence to suggest that in some people, the drugs used to treat schizophrenia may produce an increased risk for violence, largely due to agitation induced by akathisia, a side effect sometimes associated with antipsychotic medication. Similarly, abuse experienced in childhood may contribute both to a slight increase in risk for violence in adulthood, as well as the development of schizophrenia.

Violence against people with schizophrenia

Research has shown that a person diagnosed with schizophrenia is more likely to be a victim of violence (4.3% in a one month period) than the perpetrator.

Alternative approaches to schizophrenia

An approach broadly known as the anti-psychiatry movement, notably most active in the 1960s, has opposed the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argues that psychiatric patients are not ill but are just individuals with unconventional thoughts and behavior that make society uncomfortable. He argues that society unjustly seeks to control such individuals by classifying their behavior as an illness and forcibly treating them as a method of social control. It is worth noting that Szasz has never considered himself to be "anti-psychiatry" in the sense of being against psychiatric treatment, but simply believes that it should be conducted between consenting adults, rather than imposed upon anyone against his or her will. Szasz co-founded the anti-psychiatry group Citizens' Commission on Human Rights with the Church of Scientology, who are well-noted for their anti-psychiatric stance.

Similarly, psychiatrists R. D. Laing, Silvano Arieti, Theodore Lidz and other mental health professionals have argued that the symptoms of what is normally called mental illness are comprehensible reactions to impossible demands that society and particularly family life places on some sensitive individuals. Laing, Arieti and Lidz were revolutionary in valuing the content of psychotic experience as worthy of interpretation, rather than considering it simply as a secondary but essentially meaningless marker of underlying psychological or neurological distress. Laing's work, co-authored with Aaron Esterson, Sanity, Madness and the Family (1964) described eleven case studies of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and argued that the content of their actions and statements was meaningful and logical in the context of their family and life situations. Arieti's Interpretation of Schizophrenia won the 1975 scientific National Book Award in the United States. In the books Schizophrenia and the Family and The Origin and Treatment of Schizophrenic Disorders Lidz and his colleagues explain their belief that parental behaviour can result in mental illness in children.

In the 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, psychologist Julian Jaynes proposed that until the beginning of historic times, schizophrenia or a similar condition was the normal state of human consciousness. This would take the form of a "bicameral mind" where a normal state of low affect, suitable for routine activities, would be interrupted in moments of crisis by "mysterious voices" giving instructions, which early people characterized as interventions from the gods. This theory was briefly controversial. Continuing research has failed to either further confirm or refute the thesis.

Psychiatrist Tim Crow has argued that schizophrenia may be the evolutionary price we pay for a left brain hemisphere specialization for language. Since psychosis is associated with greater levels of right brain hemisphere activation and a reduction in the usual left brain hemisphere dominance, our language abilities may have evolved at the cost of causing schizophrenia when this system breaks down.

Researchers into shamanism have speculated that in some cultures schizophrenia or related conditions may predispose an individual to becoming a shaman. Certainly, the experience of having access to multiple realities is not uncommon in schizophrenia, and is a core experience in many shamanic traditions. Equally, the shaman may have the skill to bring on and direct some of the altered states of consciousness psychiatrists label as illness. Speculations regarding primary and important religious figures as having schizophrenia abound. Some commentators have endorsed the idea that major religious figures experienced psychosis, heard voices and displayed delusions of grandeur.

Alternative medicine tends to hold the view that schizophrenia is primarily caused by imbalances in the body's reserves and absorption of dietary minerals, vitamins, fats, and/or the presence of excessive levels of toxic heavy metals. The body's adverse reactions to gluten are also strongly implicated in some alternative theories (see gluten-free, casein-free diet).

One theory put forward by psychiatrists E. Fuller Torrey and R.H. Yolken is that the parasite Toxoplasma gondii leads to some, if not many, cases of schizophrenia. This is supported by evidence that significantly higher levels of Toxoplasma antibodies in schizophrenia patients compared to the general population.

An additional approach is suggested by the work of Richard Bandler who argues that "The usual difference between someone who hallucinates and someone who visualizes normally, is that the person who hallucinates doesn't know he's doing it or doesn't have any choice about it." (Time for a Change, p107). He suggests that because visualization is a sophisticated mental capability, schizophrenia is a skill, albeit an involuntary and dysfunctional one that is being used but not controlled. He therefore suggests that a significant route to treating schizophrenia might be to teach the missing skill - how to distinguish created reality from consensus external reality, to reduce its maladaptive impact, and ultimately how to exercise appropriate control over the vizualization or auditory process. Hypnotic approaches have been explored by the physician Milton H. Erickson as a means of facilitating this.

Regarding schizophrenia as a waking dreamer syndrome, Jie Zhang hypothesizes that the hallucinations of schizophrenia are caused by the activation of the continual-activation mechanism during waking, a mechanism that induces dreaming while asleep, due to the malfunction of the continual-activation thresholds in the conscious part of brain.

Portrayals of schizophrenia in the arts

The book and film A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Nash, a Nobel-Prize-winning mathematician who was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The effects of untreated schizophrenia on the family are documented in Virginia Holman's autobiography, Rescuing Patty Hearst, (Simon & Schuster 2003) The book also discusses the legal impediments to treatment that faces many schizophrenics and their families.

In Bulgakov's Master and Margarita the poet Ivan Bezdomnyj is institutionalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia after witnessing the devil (Woland) predict Berlioz's death.

See also

|

Further information about schizophrenia and approaches to it, suggested by authors such as R.D. Laing, Theodore Lidz, Emil Kraepelin, Eugene Bleuler, Karl Jaspers, Victor Tausk, Kurt Schneider and Colin Ross, as well as books, can be found within the articles for those authors.

References

- Torrey, E.F., Bowler, A.E., Taylor, E.H. & Gottesman, I.I (1994) Schizophrenia and manic depressive disorder. New York: Basic books. ISBN 0-465-07285-2

- Koskenvuo M, Langinvainio H, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Tienari P (1984) Psychiatric hospitalization in twins. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma), 33(2),321-32.

- Hoeffer A, Pollin W. (1970) Schizophrenia in the NAS-NRC panel of 15,909 veteran twin pairs. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1970 Nov; 23(5):469-77.

- Cite error: The named reference

fn_12was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

fn_75was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Riley B, Kendler KS (2006) Molecular genetic studies of schizophrenia. Eur J Hum Genet, 14 (6), 669-80.

- Day R, Nielsen JA, Korten A, Ernberg G, Dube KC, Gebhart J, Jablensky A, Leon C, Marsella A, Olatawura M et al (1987). Stressful life events preceding the acute onset of schizophrenia: a cross-national study from the World Health Organization. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 11 (2), 123–205

- ^ Harriet L. MacMillan, Jan E. Fleming, David L. Streiner, Elizabeth Lin, Michael H. Boyle, Ellen Jamieson, Eric K. Duku, Christine A. Walsh, Maria Y.-Y. Wong, William R. Beardslee. (2001) Childhood Abuse and Lifetime Psychopathology in a Community Sample. American Journal of Psychiatry,158, 1878-83.

- Schenkel, L.S., Spaulding, W.D., Dilillo, D., Silverstein, S.M. (2005) Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: Relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research

- Janssen I., Krabbendam L., Bak M., Hanssen M., Vollebergh W., De Graaf R., Van Os, J. (2004) Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, 38-45.

- Bebbington P E, Kuipers E (1994) The predictive utility of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: an aggregate analysis. Psychological Medicine, 24, 707-718.

- Van Humbeeck G, Van Audenhove C. (2003) Expressed emotion of professionals towards mental health patients. Epidemiologia e Psychiatria Sociale, 12(4), 232-235. (full text)

- Wearden AJ, Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Zastowny TR, Rahill AA. (2000) A review of expressed emotion research in health care. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 633-66.

- Van Os J. (2004) Does the urban environment cause psychosis? British Journal of Psychiatry, 184 (4), 287–288.

- Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J. (2004) Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: Follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184 (4), 293–298.

- Davies G, Welham J, Chant D, Torrey EF, McGrath J. (2003) A systematic review and meta-analysis of Northern Hemisphere season of birth studies in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29 (3), 587–93.

- Susser E, Neugebauer R, Hoek HW, Brown AS, Lin S, Labovitz D, Gorman JM (1996) Schizophrenia after prenatal famine. Further evidence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53(1), 25–31.

- Huttunen MO, Niskanen P. (1978) Prenatal loss of father and psychiatric disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35(4), 429–31.

- Brown, A.S. (2006) Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32 (2), 200-2.

- Read J, Perry BD, Moskowitz A, Connolly J (2001) The contribution of early traumatic events to schizophrenia in some patients: a traumagenic neurodevelopmental model. Psychiatry, 64, 319-45. (full text)

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Miletich RS, Kohn PD, Esposito G, Carson RE, Quarantelli M, Weinberger DR, Berman KF (2002) Reduced prefrontal activity predicts exaggerated striatal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience, 5, 267-71.

- Healy, D. (2002) The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00619-4

- Konradi C, Heckers S. (2003) Molecular aspects of glutamate dysregulation: implications for schizophrenia and its treatment. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 97(2), 153-79.

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. (2001) Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(4), 455-67.

- Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff D. (2003) Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1003, 318-27.

- Tuominen HJ, Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K. (2005) Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res, 72:225-34.

- Kinney GG, Sur C, Burno M, Mallorga PJ, Williams JB, Figueroa DJ, Wittmann M, Lemaire W, Conn PJ. (2003) The Glycine Transporter Type 1 Inhibitor. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23 (20), 7586-7591.

- Johnstone EC, Crow TJ, Frith CD, Husband J, Kreel L. (1976) Cerebral ventricular size and cognitive impairment in chronic schizophrenia. Lancet, 30;2 (7992), 924-6.

- http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/156/11/1843-b

- Flashman LA, Green MF (2004) Review of cognition and brain structure in schizophrenia: profiles, longitudinal course, and effects of treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27 (1), 1-18, vii.

- Green, M.F. (2001) Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-70334-7

- Spencer KM, Nestor PG, Perlmutter R, Niznikiewicz MA, Klump MC, Frumin M, Shenton ME, McCarley (2004) Neural synchrony indexes disordered perception and cognition in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 17288-93. (full text)

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW (2005) Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 312-324.

- Goldner EM, Hsu L, Waraich P, Somers JM (2002) Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenic disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(9), 833–43.

- Ustun TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J, and the WHO/NIH Joint Project CAR Study Group (1999). Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. Lancet, 354(9173), 111–115.

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists & The British Psychological Society (2003) Schizophrenia. Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care. London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society.

- ^ van Os J, Burns T, Cavallaro R, Leucht S, Peuskens J, Helldin L, Bernardo M, Arango C, Fleischhacker W, Lachaux B, Kane JM. (2006) Standardized remission criteria in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(2), 91-5.

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. (2005) Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353 (12), 1209-23.

- Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. (2003) New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 361(9369), 1581-9.

- Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, Carson WH, Ali M, Stock E, Stringfellow J, Ingenito G, Marder SR (2003) Aripiprazole, an Antipsychotic With a Novel Mechanism of Action, and Risperidone vs Placebo in Patients With Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 681–90.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 13(2), 261-76.

- Cormac I, Jones C, Campbell C. (2002) Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of systematic reviews, (1), CD000524.

- Zimmermann, G., Favrod, J., Trieu, V. H., & Pomini, V. (2005) The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 77, 1-9.

- Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, Bray P, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J. (2002) Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 144-52.

- Kulhara P. (1994) Outcome of schizophrenia: some transcultural observations with particular reference to developing countries. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 244(5), 227–35.

-

Crawford, Mike J. (2006). "Music therapy for in-patients with schizophrenia: Exploratory randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry (2006). 189: 405–409.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - Burton, R. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Cf. especially subsection 3, on and after line 3480, "Music a Remedy".

- Peet M, Stokes C. (2005) Omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Drugs, 65(8), 1051-9.

- Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, Strauss JS, Breier A. (1987) The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, II: Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(6), 727–35.

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM (2004) Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 473-479.

- Hopper K, Wanderling J (2000) Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26 (4), 835-46.

- Hannerz H, Borga P, Borritz M. (2001) Life expectancies for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. Public Health, 115 (5), 328-37.

- Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, Sweeney JA (1999) Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(10), 1590–5.

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. (1990) Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(4), 571–89.

- Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Canive JM, Miller del D, Reimherr F, McGee M, Khan A, Van Dorn R, Rosenheck RA, Lieberman JA. (2006) Substance use in persons with schizophrenia: baseline prevalence and correlates from the NIMH CATIE study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(3), 164-72.

- Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray RM. (2004) Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 110-7. (full text)

- Cite error: The named reference

fn_49was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Zammit S, Allebeck P, Dalman C, Lundberg I, Hemmingsson T, Lewis (2003) Investigating the association between cigarette smoking and schizophrenia in a cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160 (12), 2216–21.

- Walsh E, Gilvarry C, Samele C, Harvey K, Manley C, Tattan T, Tyrer P, Creed F, Murray R, Fahy T (2004) Predicting violence in schizophrenia: a prospective study. Schizophrenia Research, 67(2-3), 247-52.

- Simpson AI, McKenna B, Moskowitz A, Skipworth J, Barry-Walsh J. (2004) Homicide and mental illness in New Zealand, 1970-2000. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 394-8.

- Fazel S, Grann M. (2004) Psychiatric morbidity among homicide offenders: a Swedish population study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(11), 2129-31.

- Leong GB, Silva JA. (2003) Neuroleptic-induced akathisia and violence: a review. Journal of Forensic Science, 48

- Fitzgerald PB, de Castella AR, Filia KM, Filia SL, Benitez J, Kulkarni J. (2005) Victimization of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(3), 169-74. (1), 187-9.

- Crow, T. J. (1997) Schizophrenia as failure of hemispheric dominance for language. Trends in Neurosciences, 20(8), 339–343.

- Polimeni J, Reiss JP. (2002) How shamanism and group selection may reveal the origins of schizophrenia. Medical Hypothesis, 58(3), 244–8.

- Torrey EF, Yolken RH. (2003) Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 9 (11), 1375-80.

- Wang HL, et al. (2006) Prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in first-episode schizophrenia and comparison between Toxoplasma-seropositive and Toxoplasma-seronegative schizophrenia, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114 (1), 40-48.

- Zhang, Jie (2005) Continual-activation theories of schizophrenia and restless legs syndrome, Dynamical Psychology.

Further reading

- Bentall, R. (2003) Madness explained: Psychosis and Human Nature. London: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7139-9249-2

- Boyle, Mary, (1993), Schizophrenia: A Scientific Delusion, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09700-2 (Amazon Review).

- Deveson, Anne (1991), "Tell Me I'm Here" NON-FICTION: Schizophrenics - biography - family relationships. ISBN 0-14-027257-7 PENGUIN GROUP Australia. Printed 1991 & 1998.

- Fallon, J.H. et. al. (2003) The Neuroanatomy of Schizophrenia: Circuitry and Neurotransmitter Systems. Clinical Neuroscience Research 3:77-107.

- Green, M.F. (2001) Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-70334-7

- Jones, S. and Hayward, P. (2004) Coping with Schizophrenia: A Guide for Patients, Families and Caregivers. ISBN 1-85168-344-5

- Keen, T. M. (1999) Schizophrenia: orthodoxy and heresies. A review of alternative possibilities. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 1999, 6, 415-424. PDF. An article reviewing the dominant (orthodox) and alternative (heretical) theories, hypotheses and beliefs about schizophrenia.

- Read, J., Mosher, L.R., Bentall, R. (2004) Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. ISBN 1-58391-906-6. A critical approach to biological and genetic theories, and a review of social influences on schizophrenia.

- Szasz, T. (1976) Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07222-4

- Viktor Tausk : "Sexuality, War, and Schizophrenia: Collected Psychoanalytic Papers", Publisher: Transaction Publishers 1991, ISBN 0-88738-365-3 (On the Origin of the 'Influencing Machine' in Schizophrenia.)

- Torrey, E.F., M.D. (2006) Surviving Schizophrenia: A Manual for Families, Consumers, and Providers (5th Edition). Quill (HarperCollins Publishers) ISBN 0-06-084259-8

- Vonnegut, M. The Eden Express. ISBN 0-553-02755-7. A personal account of schizophrenia.

External links

News, information and further description

- - DSM V scholarly debates on schizophrenia

- - NPR: the sight and sounds of schizophrenia

- National Mental Health Association fact sheet on schizophrenia

- Understanding Schizophrenia - A factsheet from the mental health charity Mind

- DSM-IV-TR Full diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia

- World Health Organisation data on schizophrenia from 'The World Health Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope'

- National Institute of Mental Health (USA) Schizophrenia information

- Childhood Schizophrenia Summary

- UCLA Laboratory of Neuro Imaging definition

- The current World Health Organisation definition of Schizophrenia

- A directory of free full-text articles on diagnosis and management of schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia by WebMD (pharmaceutical company sponsored).

- Schizophrenia.com - information and support site

- Schizophrenia in history

- Symptoms in Schizophrenia Film made in 1940 showing some of the symptoms of Schizophrenia.

- http://www.sciencedaily.com/news/mind_brain/schizophrenia/

- Open The Doors - information on global programme to fight stigma and discrimination because of Schizophrenia. The World Psychiatric Association (WPA)

- Scientific American Magazine (January 2004 Issue) Decoding Schizophrenia

- Alternative view on schizophrenia as a mental healing process

Charities and support groups

- Schizophrenics Anonymous

- SANE UK mental health charity focused on schizophrenia that supports sufferers, runs a helpline and carries out research into mental illness

- The Schizophrenia Association of Great Britain

- CASL The Campaign for Abolition of the Schizophrenia Label.

Critical approaches to schizophrenia

- Successfulschizophrenia.org A website critical of Schizophrenia as a disorder, with many links and resources, by Al Siebert, psychologist Ph.D.

- Schizophrenia: A Nonexsistent Disease by Lawrence Stevens, J.D

- Loren Mosher, M.D. (Chief of the Center for Studies of Schizophrenia at the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health 1969-1980) Still Crazy After All These Years

- Bola, John R., Ph.D.; & Mosher, Loren R., M.D. (2003). Treatment of Acute Psychosis Without Neuroleptics: Two-Year Outcomes From the Soteria Project. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, (191: 219-229). Available as PDF.

- Jonathan Leo, Ph.D., & Jay Joseph, Psy.D. Schizophrenia: Medical students are taught it's all in the genes, but are they hearing the whole story?

Categories: