| Revision as of 00:30, 11 January 2005 edit24.66.94.140 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:15, 11 January 2005 edit undoShanes (talk | contribs)Administrators30,020 editsm rv vandalism by 24.66.94.140Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

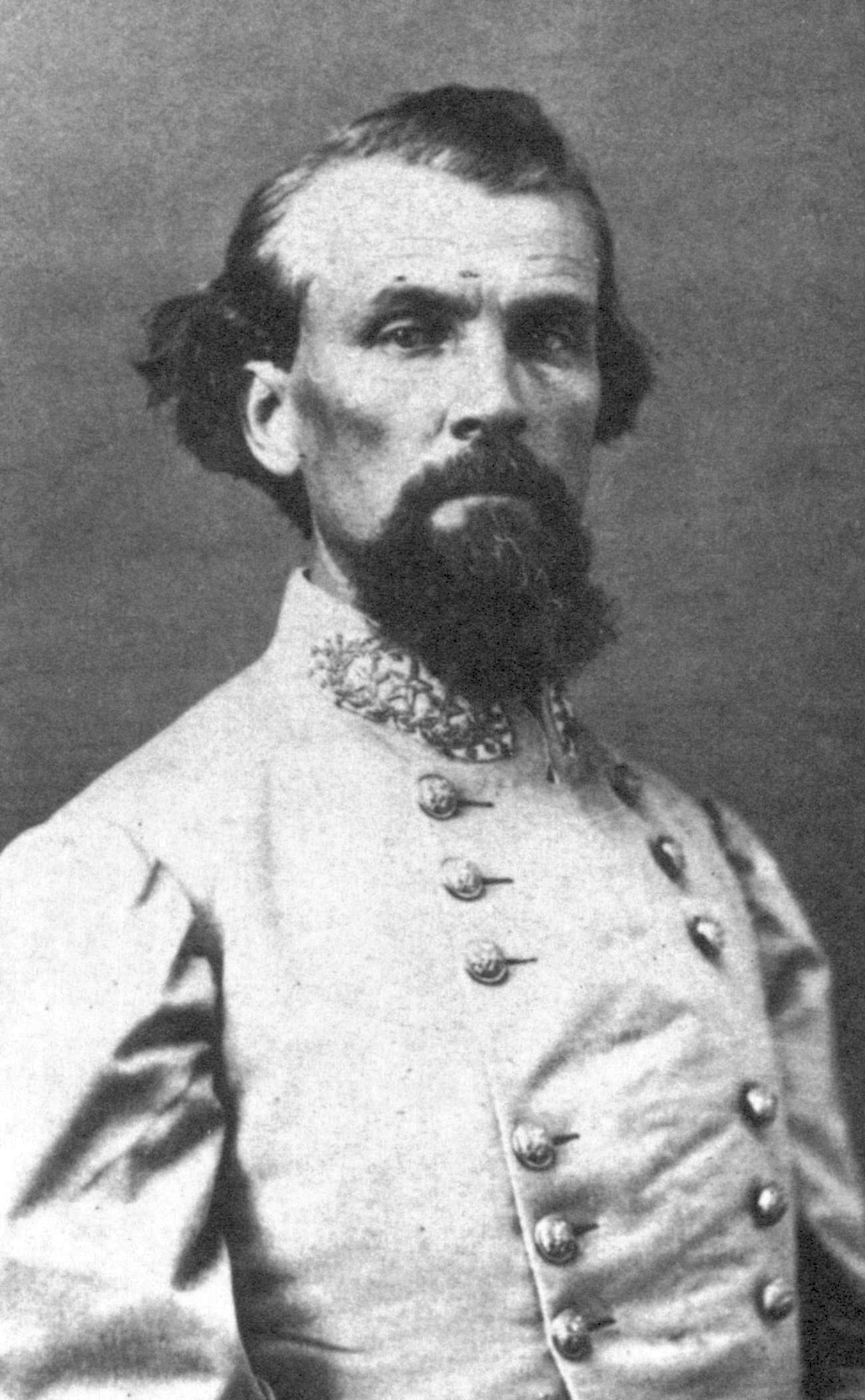

| '''Nathan Bedford Forrest''' (], ] - ], ]), perhaps the ]'s most highly regarded ] officer, and one of the war's most innovative and successful ]s, developed tactics that soldiers still study even today. After the war, he became the first leader of the ], a move that forever marred his military career. | |||

| this page is a fucken joke | |||

| ] | |||

| == Early Life == | |||

| Forrest was born to a poor middle ] family on July 13, 1821 in the ] town of ]. Forrest became the head of his family at the age of 17, following his father's death, and despite having no formal education, he determined to pull himself and his family up from the poverty that enmired them. Ultimately, he became a ]man, a ] owner and a ]. He put his younger brothers through college, provided for his mother and by the time the American Civil War broke out in ], had become a millionaire, one of the richest men in the ]. | |||

| == Military Career == | |||

| Given that Forrest earned much of his money in the slave trade, he naturally favored the ] side in the war. Using his own money, he raised and equipped a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers to fight in the Confederate army. Forrest himself wanted no more than to fight for the ] as a private, but because of his prominence in society and the fact he had raised the troops himself, he ended up as their commanding officer, with the rank of ]. He knew almost nothing of military operations, but applied himself diligently to learn, and soon became a competent officer. | |||

| Forrest's efforts did not go unnoticed, and he soon won promotion to ] and gained command of a Confederate cavalry brigade. He first distinguished himself in battle at the ] in February ], when he led a breakout from a siege by the Union army. He had tried to persuade his superiors of the feasibility of retreating out of the fort across the ], but they refused to listen. Forrest angrily walked out of a meeting and declared that he had not led his men into battle to surrender. He proved his point when nearly 4,000 troops followed him across the river to fight again. A few days later, with the fall of ] imminent, Forrest took command of the city and evacuated several government officials and removed millions of dollars in heavy machinery used to make weapons - something the Confederacy could ill afford to lose. | |||

| A month later, Forrest was back in action at the ] (] - ] ]). Once again, he found himself in command of the Confederate rear guard after a lost battle, and again he distinguished himself. For the first time, he came under enemy fire and showed himself to have no fear. He charged a line of Union skirmishers, drove them off, but was wounded in the process. Forrest allegedly became the battle's last casualty. | |||

| He quickly recovered from the injury and was back in the saddle that summer, in command of a new brigade of green cavalry regiments. In July, he led them back into middle Tennessee after receiving an order from the commanding general, Gen. ], to launch a cavalry raid. It proved a stunning success. On Forrest's birthday, ] ], his men descended on the Union-held city of ], defeating and then capturing a force of twice their numbers. | |||

| This proved just the first of many victories Forrest would win; he remained undefeated in battle until the final days of the war, when he faced overwhelming numbers. But he and Bragg could not get along, and the Confederate high command did not realize the degree of Forrest's talent until far too late in the war. In their postwar writings, both Confederate President ] and General ] lamented this oversight. | |||

| In December ], Forrest again received a new command, this one composed of about 2,000 green recruits, most of whom lacked even weapons with which to fight. Again, Bragg ordered a raid, this one into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under general ], threatening the city of ], ]. | |||

| Forrest protested that to send these untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. On the ensuing raid, he again showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" trying to locate his fast-moving forces. Forrest never stayed in one place long enough to be located, raided as far north as the banks of the ] in southwest ], and came back to his base in ] with more men than he'd left with, and all of them fully armed with captured Union weapons. | |||

| Forrest continued to lead his men in smaller-scale operations until April of ], when the Confederate army dispatched him into the backcountry of northern ] and west ] to deal with an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen under the command of Col. ]. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of ], which would have cut off Bragg's supply line and forced him to retreat into Georgia. Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way, until Streight's lone objective became simply to escape his relentless pursuer. Finally, on ], Forrest caught up with Streight at ] and took 1,700 prisoners. | |||

| Forrest served with the main army at the ] (] - ] ]), where he pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners. Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, and not long after, Forrest and Bragg had a confrontation which resulted in Forrest's re-assignment to an independent command in ]. | |||

| Forrest went to work and soon raised a 6,000-man force of his own, which he led back into west Tennessee. He did not have the resources to retake the area and hold it, but he did have enough force to render it useless to the Union army. He led several more raids into the area, one of which ended in the controversial ] on ], ]. In that battle, Forrest demanded unconditional surrender, or else he would "put every man to the sword" - language he frequently used to expedite a surrender. The battle's details remain disputed and controversial to this day. What is known is that Forrest's men stormed the lightly guarded fort, inflicting heavy casualties on its defenders who quickly fell into disarray as the Union command - already short several officers - collapsed. Conflicting reports of what happened next are the source of controversy. Some alleged that the Confederates targeted several hundred ] soldiers inside the fort, though one battle account says the killing was indiscriminate. Only 80 out of approximately 262 blacks survived the battle. Casualties were also high among white defenders of the fort, with 164 out of about 295 surviving. After the battle reports surfaced of captured solders being subjected to brutality including allegations that they were crucified on tent frames and burnt alive. Whether or not these reports are accurate will probably never be known for certain as both sides used the battle as a political rallying cry and were prone to exaggerate the events. Forrest himself does not appear to have participated in or sanctioned brutality in the battle as witnesses report his efforts to reign in his troops after arriving on the front line. | |||

| Forrest's greatest victory came on ], ], when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,100 men commanded by General ] at the ]. Here, his mobility of force (he deployed his men as ]) and superior tactics won a remarkable victory, inflicting 2,500 casualties against a loss of 492, and sweeping the Union forces completely from a large expanse of southwest Tennessee and northern Mississippi. | |||

| Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown ] in August ], and another on a huge Union supply depot at ] on ], ], causing millions of dollars in damage. In December, he fought alongside the Confederate ] in the disastrous campaign that ended in the ] (] - ] ]), distinguishing himself by commanding the Confederate rearguard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant general. | |||

| In ], Forrest attempted without success to defend the state of ] against Union attacks, but he still had an army in the field in April, when news of Lee's surrender reached him. He was urged to flee to ], but chose to share the fate of his men, and surrendered. Forrest was later cleared of any violations of the rules of war in regard to Fort Pillow, and was allowed to return to private life. | |||

| Forrest was one of the first men, if not the first, to grasp the doctrines of "]" that became prevalent in the ]. His one directive to his men was to "get there firstest with the mostest", even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, which he did more than once. A total of 29 horses were shot out from under him. Forrest's victory at Brice's Cross Roads became the subject of a class taught at the French War College by Marshal ] before ], and his mobile campigns were studied by the ] general ], who as commander of the ] in ] emulated his tactics on a wider scale, with tanks and trucks. | |||

| Shortly after the war, Lee was asked to identify the best soldier he ever commanded. Although Forrest only came under his command in the last month of the war, when Lee became overall Confederate commander, Lee replied: "A man I have never met, sir. His name is Forrest." | |||

| == Postwar Activities == | |||

| Forrest lost almost all his fortune during the war, since much of it was invested in slaves, and of what was left, he gave much to the men who had served under him, but who had come home to find they had nothing. | |||

| Embittered by the state of his homeland after the war, in May ], Forrest became "Grand Wizard" of the ], an organization of Confederate veterans. Because of Forrest's prominence, the organization grew rapidly under his ]. In addition to aiding Confederate widows and orphans of the war, many members of the new group began to use force to oppose the extension of voting rights to blacks, and to resist Reconstruction-introduced measures for the ending of segregation. In ], Forrest, disagreeing with its increasingly violent tactics, ordered the Klan to disband. However, many of its groups in other parts of the country ignored the order and continued to function. | |||

| Forrest returned to private business in the Memphis area and remained engaged in such for the rest of his life. In his final years, Forrest encouraged his followers to live in peace with the freed slaves who lived among them. He also continued to support his old soldiers so long as he lived; and when he died on ], ], of ], thousands of them congregated at his funeral. His funeral oration was given by his former boss, ] himself. Forrest was buried on ], ], in ]. His remains were moved to Forrest Park, a Memphis city park, in ]. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| Forrest's great-grandson, ], also followed a military career, reaching the rank of ] in the ] during ] before being killed in action in ], while on a bombing raid over Germany. | |||

| In the motion picture '']'', Tom Hanks' character Forrest Gump states that he was named after Nathan Bedford Forrest. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 01:15, 11 January 2005

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 - October 29, 1877), perhaps the American Civil War's most highly regarded cavalry officer, and one of the war's most innovative and successful generals, developed tactics that soldiers still study even today. After the war, he became the first leader of the Ku Klux Klan, a move that forever marred his military career.

Early Life

Forrest was born to a poor middle Tennessee family on July 13, 1821 in the Bedford County town of Chapel Hill. Forrest became the head of his family at the age of 17, following his father's death, and despite having no formal education, he determined to pull himself and his family up from the poverty that enmired them. Ultimately, he became a businessman, a plantation owner and a slave trader. He put his younger brothers through college, provided for his mother and by the time the American Civil War broke out in 1861, had become a millionaire, one of the richest men in the U.S. South.

Military Career

Given that Forrest earned much of his money in the slave trade, he naturally favored the Confederate side in the war. Using his own money, he raised and equipped a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers to fight in the Confederate army. Forrest himself wanted no more than to fight for the Confederacy as a private, but because of his prominence in society and the fact he had raised the troops himself, he ended up as their commanding officer, with the rank of Colonel. He knew almost nothing of military operations, but applied himself diligently to learn, and soon became a competent officer.

Forrest's efforts did not go unnoticed, and he soon won promotion to Brigadier General and gained command of a Confederate cavalry brigade. He first distinguished himself in battle at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862, when he led a breakout from a siege by the Union army. He had tried to persuade his superiors of the feasibility of retreating out of the fort across the Cumberland River, but they refused to listen. Forrest angrily walked out of a meeting and declared that he had not led his men into battle to surrender. He proved his point when nearly 4,000 troops followed him across the river to fight again. A few days later, with the fall of Nashville imminent, Forrest took command of the city and evacuated several government officials and removed millions of dollars in heavy machinery used to make weapons - something the Confederacy could ill afford to lose.

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the Battle of Shiloh ( 6 - 7 April 1862). Once again, he found himself in command of the Confederate rear guard after a lost battle, and again he distinguished himself. For the first time, he came under enemy fire and showed himself to have no fear. He charged a line of Union skirmishers, drove them off, but was wounded in the process. Forrest allegedly became the battle's last casualty.

He quickly recovered from the injury and was back in the saddle that summer, in command of a new brigade of green cavalry regiments. In July, he led them back into middle Tennessee after receiving an order from the commanding general, Gen. Braxton Bragg, to launch a cavalry raid. It proved a stunning success. On Forrest's birthday, 13 July 1862, his men descended on the Union-held city of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, defeating and then capturing a force of twice their numbers.

This proved just the first of many victories Forrest would win; he remained undefeated in battle until the final days of the war, when he faced overwhelming numbers. But he and Bragg could not get along, and the Confederate high command did not realize the degree of Forrest's talent until far too late in the war. In their postwar writings, both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee lamented this oversight.

In December 1862, Forrest again received a new command, this one composed of about 2,000 green recruits, most of whom lacked even weapons with which to fight. Again, Bragg ordered a raid, this one into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under general Ulysses S. Grant, threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Forrest protested that to send these untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. On the ensuing raid, he again showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" trying to locate his fast-moving forces. Forrest never stayed in one place long enough to be located, raided as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky, and came back to his base in Mississippi with more men than he'd left with, and all of them fully armed with captured Union weapons.

Forrest continued to lead his men in smaller-scale operations until April of 1863, when the Confederate army dispatched him into the backcountry of northern Alabama and west Georgia to deal with an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen under the command of Col. Abel Streight. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, which would have cut off Bragg's supply line and forced him to retreat into Georgia. Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way, until Streight's lone objective became simply to escape his relentless pursuer. Finally, on May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight at Rome, Georgia and took 1,700 prisoners.

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga (18 September - 20 September 1863), where he pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners. Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, and not long after, Forrest and Bragg had a confrontation which resulted in Forrest's re-assignment to an independent command in Mississippi.

Forrest went to work and soon raised a 6,000-man force of his own, which he led back into west Tennessee. He did not have the resources to retake the area and hold it, but he did have enough force to render it useless to the Union army. He led several more raids into the area, one of which ended in the controversial Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864. In that battle, Forrest demanded unconditional surrender, or else he would "put every man to the sword" - language he frequently used to expedite a surrender. The battle's details remain disputed and controversial to this day. What is known is that Forrest's men stormed the lightly guarded fort, inflicting heavy casualties on its defenders who quickly fell into disarray as the Union command - already short several officers - collapsed. Conflicting reports of what happened next are the source of controversy. Some alleged that the Confederates targeted several hundred African American soldiers inside the fort, though one battle account says the killing was indiscriminate. Only 80 out of approximately 262 blacks survived the battle. Casualties were also high among white defenders of the fort, with 164 out of about 295 surviving. After the battle reports surfaced of captured solders being subjected to brutality including allegations that they were crucified on tent frames and burnt alive. Whether or not these reports are accurate will probably never be known for certain as both sides used the battle as a political rallying cry and were prone to exaggerate the events. Forrest himself does not appear to have participated in or sanctioned brutality in the battle as witnesses report his efforts to reign in his troops after arriving on the front line.

Forrest's greatest victory came on June 10, 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,100 men commanded by General Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads. Here, his mobility of force (he deployed his men as mounted infantry) and superior tactics won a remarkable victory, inflicting 2,500 casualties against a loss of 492, and sweeping the Union forces completely from a large expanse of southwest Tennessee and northern Mississippi.

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864, and another on a huge Union supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee on October 3, 1864, causing millions of dollars in damage. In December, he fought alongside the Confederate Army of Tennessee in the disastrous campaign that ended in the Battle of Nashville (15 December - 16 December 1864), distinguishing himself by commanding the Confederate rearguard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant general.

In 1865, Forrest attempted without success to defend the state of Alabama against Union attacks, but he still had an army in the field in April, when news of Lee's surrender reached him. He was urged to flee to Mexico, but chose to share the fate of his men, and surrendered. Forrest was later cleared of any violations of the rules of war in regard to Fort Pillow, and was allowed to return to private life.

Forrest was one of the first men, if not the first, to grasp the doctrines of "mobile warfare" that became prevalent in the 20th century. His one directive to his men was to "get there firstest with the mostest", even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, which he did more than once. A total of 29 horses were shot out from under him. Forrest's victory at Brice's Cross Roads became the subject of a class taught at the French War College by Marshal Ferdinand Foch before World War I, and his mobile campigns were studied by the German general Erwin Rommel, who as commander of the Afrika Korps in World War II emulated his tactics on a wider scale, with tanks and trucks.

Shortly after the war, Lee was asked to identify the best soldier he ever commanded. Although Forrest only came under his command in the last month of the war, when Lee became overall Confederate commander, Lee replied: "A man I have never met, sir. His name is Forrest."

Postwar Activities

Forrest lost almost all his fortune during the war, since much of it was invested in slaves, and of what was left, he gave much to the men who had served under him, but who had come home to find they had nothing.

Embittered by the state of his homeland after the war, in May 1866, Forrest became "Grand Wizard" of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization of Confederate veterans. Because of Forrest's prominence, the organization grew rapidly under his leadership. In addition to aiding Confederate widows and orphans of the war, many members of the new group began to use force to oppose the extension of voting rights to blacks, and to resist Reconstruction-introduced measures for the ending of segregation. In 1869, Forrest, disagreeing with its increasingly violent tactics, ordered the Klan to disband. However, many of its groups in other parts of the country ignored the order and continued to function.

Forrest returned to private business in the Memphis area and remained engaged in such for the rest of his life. In his final years, Forrest encouraged his followers to live in peace with the freed slaves who lived among them. He also continued to support his old soldiers so long as he lived; and when he died on October 29, 1877, of diabetes, thousands of them congregated at his funeral. His funeral oration was given by his former boss, Jefferson Davis himself. Forrest was buried on October 30, 1877, in Elmwood Cemetery. His remains were moved to Forrest Park, a Memphis city park, in 1904.

Legacy

Forrest's great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, also followed a military career, reaching the rank of Brigadier General in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II before being killed in action in 1943, while on a bombing raid over Germany.

In the motion picture Forrest Gump, Tom Hanks' character Forrest Gump states that he was named after Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Categories: