| Revision as of 21:57, 28 January 2021 view sourceBerig (talk | contribs)Administrators32,494 editsm →Scandinavian sources← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:03, 28 January 2021 view source Berig (talk | contribs)Administrators32,494 edits →Byzantine sources: add runestone pictureTag: nowiki addedNext edit → | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

| ===Byzantine sources=== | ===Byzantine sources=== | ||

| :''Further information: ] and ]''<!-- Further template not used due to disambig tags. Please restore this template once disambiguated {{Further|Rus'–Byzantine War|Rus'–Byzantine Treaty}}--> | :''Further information: ] and ]''<!-- Further template not used due to disambig tags. Please restore this template once disambiguated {{Further|Rus'–Byzantine War|Rus'–Byzantine Treaty}}--> | ||

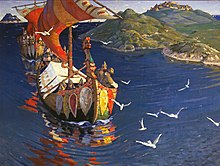

| ], which tells of two locations at the Dniepr cataracts, ''Eifor'' (one of the rapids) and ''Rufstain'' (''Rvanyj Kamin<nowiki>'</nowiki>'').]] | |||

| When the Varangians first appeared in ] (the ] in the 820s and the ] in 860), the Byzantines seem to have perceived the ''Rhos'' ({{lang-el|Ῥώς}}) as a different people from the Slavs. At least no source says they are part of the Slavic race. Characteristically, pseudo-] and ] refer to the Rhos as ''dromitai'' (Δρομῖται), a word related to the Greek word meaning ''a run'', <!--Modern Greek speaker perceives the word Dromitai as meaning "someone walking from place to place without a permanent home"--> suggesting the ].<ref name="VoltPäll2005">{{cite book|last1=Volt|first1=Ivo|author2=Janika Päll|title=Byzantino-Nordica 2004: Papers Presented at the International Symposium of Byzantine Studies Held on 7-11 May 2004 in Tartu, Estonia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gItVKprpx7sC&pg=PA16|access-date=28 September 2016|year=2005|publisher=Morgenstern Society|isbn=978-9949-11-266-1|page=16}}</ref> | |||

| In his treatise '']'', ] describes the Rhos as the neighbours of ] who buy from the latter cows, horses, and sheep "because none of these animals may be found in Rhosia". His description represents the Rus' as a warlike northern tribe. Constantine also enumerates the names of the ] cataracts in both rhosisti ('ῥωσιστί', the language of the Rus') and sklavisti ('σκλαβιοτί', the language of the Slavs). The Rus' names can most readily be etymologised as ], and have been argued to be older than the Slavic names:<ref name="auto4">H. R. Ellis Davidson, ''The Viking Road to Byzantium'' (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976), p. 83.p. 83.</ref><ref name="Blöndal20079">{{cite book|author=Sigfús Blöndal|title=The Varangians of Byzantium|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vFRug14ui7gC&pg=PA9|date=16 April 2007|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-03552-1|page=9}}</ref> | In his treatise '']'', ] describes the Rhos as the neighbours of ] who buy from the latter cows, horses, and sheep "because none of these animals may be found in Rhosia". His description represents the Rus' as a warlike northern tribe. Constantine also enumerates the names of the ] cataracts in both rhosisti ('ῥωσιστί', the language of the Rus') and sklavisti ('σκλαβιοτί', the language of the Slavs). The Rus' names can most readily be etymologised as ], and have been argued to be older than the Slavic names:<ref name="auto4">H. R. Ellis Davidson, ''The Viking Road to Byzantium'' (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976), p. 83.p. 83.</ref><ref name="Blöndal20079">{{cite book|author=Sigfús Blöndal|title=The Varangians of Byzantium|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vFRug14ui7gC&pg=PA9|date=16 April 2007|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-03552-1|page=9}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 22:03, 28 January 2021

For other uses of "Rus", see Rus (disambiguation). Ethnic group

The Rus' people (Old East Slavic: Рѹсь; Modern Belarusian, Russian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian: Русь, romanised: Rus'; Old Norse: Garðar; Greek: Ῥῶς, romanised: Rhos) were an ethnos in early medieval eastern Europe. The scholarly consensus holds that they were originally Norse people, mainly originating from Sweden, settling and ruling along the the river-routes between the Baltic and the Black Seas from around the 8th to 11th centuries AD. They formed a state known as Kievan Rus', which was initially a multiethnic society where the ruling Norsemen merged and assimilated with Slavic, Baltic and Finnic tribes, ending up with Old East Slavic as their common language. Kievan Rus' remained a tributary to the Swedish kings into the 11th century.

The history of the Rus' is central to 9th through 10th-century state formation, and thus national origins, in eastern Europe (ultimately giving their name to Russia and Belarus). They are relevant to the national histories of Russia, Ukraine, Sweden, Poland, Belarus, Finland and the Baltic states. Because of this importance, there is a set of alternative so-called "Anti-Normanist" views that are largely confined to a minor group of East European scholars.

Etymology

Main article: Rus' (name)

The name Rus' remains not only in names such as Russia and Belarus, but it is also preserved in many place names in the Novgorod and Pskov districts, and it is the origin of the Greek Rōs. Rus is generally considered to be a borrowing from Finnish Ruotsi ("Sweden"), which in turn is derived either from OEN rōþer (OWN róðr), and which referred to rowing, the fleet levy, etc., or it is derived from Rōþin (which also contains the root rōþer), an older name for the Swedish coastal region Roslagen. The Finnish and Russian forms of the name have a final -s revealing an original compound where the first element was rōþ(r)s- (before a voiceless consonant þ is pronounced like th in English thing).

The prefix form rōþs- is not only found in Ruotsi and Rus', but also in Old Norse róþsmenn and róþskarlar, both meaning "rowers", and in the modern Swedish name for the people of Roslagen - rospiggar which derives from ON *rōþsbyggiar ("inhabitants of Rōþin"). The name Roslagen itself is formed with this element and the plural definite form of the neuter noun lag, meaning "the teams", referring to the teams of rowers in the Swedish kings' fleet levy.

There is one, probably two, instances of the root in Old Norse from two 11th c. runic inscriptions that fittingly are located at two extremes of the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks. One of them is roþ for rōþer /róðr, meaning "fleet levy", on the runestone U 11 in the old Swedish heartland in the Mälaren Valley, and the other one was identified by Erik Brate in the most widely accepted reading as roþ(r)slanti on the Piraeus Lion originally located in Athens, where a runic inscription was most likely carved by Swedish mercenaries serving in the Varangian Guard. Brate has reconstructed *Rōþsland, as an old name for Roslagen.

Other theories such as derivation from Rusa, a name for the Volga, are rejected or ignored by mainstream scholarship.

History

Further information: Norsemen, Vikings, and Varangians

Having settled Aldeigja (Ladoga) in the 750s, Scandinavian colonists played an important role in the early ethnogenesis of the Rus' people, and in the formation of the Rus' Khaganate. The Varangians (Varyags, in Old East Slavic) are first mentioned by the Primary Chronicle as having exacted tribute from the Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859. It was the time of rapid expansion of the Vikings' presence in Northern Europe; England began to pay Danegeld in 865, and the Curonians faced an invasion by the Swedes around the same time.

The Varangians being first mentioned in the Primary Chronicle suggests that the term Rus' was used to denote Scandinavians until it became firmly associated with the now extensively Slavicised elite of Kievan Rus. At that point, the new term Varangian was increasingly preferred to name Scandinavians, probably mostly from what is currently Sweden, plying the river routes between the Baltic and the Black and Caspian Seas.

Due largely to geographic considerations, it is often postulated that most of the Varangians who traveled and settled in the lands of the eastern Baltic, the lands of the modern-day Russian Federation and the lands to the south came from the area of modern-day Sweden. Relatively few of the rune stones Varangians left in their native Sweden tell of their journeys abroad, to such places as what is today Russia, Ukraine, Greece, and Italy. Most of these rune stones can be seen today, and are a significant piece of historical evidence. The Varangian runestones tell of many notable Varangian expeditions, and even account for the fates of individual warriors and travelers.

In Russian history, two cities are used to describe the beginnings of the country: Kiev and Novgorod. In the first part of the 11th century the former was already a Slav metropolis, rich and powerful, a fast growing centre of civilisation adopted from Byzantium. The latter town, Novgorod, was another centre of the same culture but founded in different surroundings, where some old local traditions moulded this commercial city into a mighty oligarchic republic of a kind otherwise unknown in this part of Europe. These towns have tended to overshadow the significance of other places that had existed long before Kiev and Novgorod were founded. The two original centres of Rus were Staraja Ladoga and Rurikovo Gorodishche, two points on the Volkhov, a river running for 200 km between Lake Ilmen in the south to Lake Ladoga in the north. This was the territory that most probably was originally called by the Norsemen Gardar, a name that long after the Viking Age acquired a much broader meaning and became Gardariki, a denomination for the entire Old Russian State. The area between the lakes was the original Rus', and it was from here that its name was transferred to the Slav territories on the middle Dnieper, which eventually became Rus' (Ruskaja zemlja). (According to prominent Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak, the Novgorod people up until the 14th century did not call themselves Rus', and used the term Rus' only for the Kiev, Pereyaslavl and Chernigov principalities.)

The pre-history of the first territory of Rus' has been sought in the developments around the early-8th century, when Staraja Ladoga was founded as a manufacturing centre and to conduct trade, serving the operations of Scandinavian hunters and dealers in furs obtained in the north-eastern forest zone of Eastern Europe. In the early period (the second part of the 8th and first part of the 9th century), a Norse presence is only visible at Staraja Ladoga, and to a much lesser degree at a few other sites in the northern parts of Eastern Europe. The objects that represent Norse material culture of this period are rare outside Ladoga and mostly known as single finds. This rarity continues throughout the 9th century until the whole situation changes radically during the next century, when historians meet, at many places and in relatively large quantities, the material remains of a thriving Scandinavian culture. For a short period of time, some areas of Eastern Europe became as much part of the Norse world as were Danish and Norwegian territories in the West. The culture of the Rus' contained Norse elements used as a manifestation of their Scandinavian background. These elements, which were current in 10th-century Scandinavia, appear at various places in the form of collections of many types of metal ornaments, mainly female but male also, such as weapons, decorated parts of horse bridles, and diverse objects embellished in contemporaneous Norse art styles.

The Swedish king Anund Jakob wanted to assist Yaroslav the Wise, Grand prince of Kiev, in his campaigns against the Pechenegs. The so-called Ingvar the Far-Travelled, a Swedish Viking who wanted to conquer Georgia, also assisted Yaroslav with 3000 men in the war against the Pechenegs; however, he later continued on to Georgia. Yaroslav the Wise married the Swedish king's daughter, Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden, who became the Russian saint, Anna, while Harald Hardrada, the Norwegian king who was a military commander of the Varangian guard, married Elisiv of Kiev. The two first uncontroversially historical Swedish kings Eric the Victorious and Olof Skötkonung both had Slavic wives. Danish kings and royals also frequently had Slavic wives. For example, Harald Bluetooth married Tove of the Obotrites. Vikings also made up the bulk of the bodyguards of early Kievan Rus' rulers.

Evidence for strong bloodline connexions between the Kievan Rus' and Scandinavia existed and a strong alliance between Vikings and early Kievan rulers is indicated in early texts of Scandinavian and East Slavic history. Several thousand Swedish Vikings died for the defence of Kievan Rus' against the Pechenegs. Anund Jacob, the Swedish king, was referred to as Amunder a Ruzzia by the chronicler Adam of Bremen.

Scandinavian sources

When the Norse sagas were put to text in the 13th century, the Norse colonisation of Eastern Europe was a distant past, and little of historical value can be extracted. In the sagas, the area is called Garðaríki, the "realm of cities", where the legendary kings have Norse names, and Snorri Sturluson mentions the name 'Great Sweden' (Svíþjóð hin mikla) in Heimskringla. There is, however, more reliable information from the 11th and the 12th centuries, but at that time most of the Scandinavian population had already assimilated, and the term Rus' referred to a largely Slavic-speaking population.

The most contemporary sources are the runestones, but just like the sagas, the vast majority of them arrive relatively late. The earliest runestone that tells of eastwards voyages is the Kälvesten runestone from the 9th century in Östergötland, but it does not specify where the expedition had gone. It was Harald Bluetooth's construction of the Jelling stones in the late 10th century that started the runestone fashion that resulted in the raising of thousands of runestones in Sweden, during the 11th century, and at that time the Swedes arrived as mercenaries and traders rather than settlers. In the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries runic memorials had consisted of runes on wooden poles that were erected in the ground, something which explains the lack of runic inscriptions from this period both in Scandinavia and in eastern Europe as wood is perishable. This tradition was described by Ibn Fadlan who met Scandinavians on the shores of the Volga.

Slavic sources

The earliest Slavonic-language narrative account of Rus' history is the Primary Chronicle, compiled and adapted from a wide range of sources in Kiev at the start of the 13th century. It has therefore been influential in modern history-writing, but it was also compiled much later than the time it describes, and historians agree it primarily reflects the political and religious politics of the time of Mstislav I of Kiev.

However, the chronicle does include the texts of a series of Rus'–Byzantine Treaties from 911, 945, and 971. The Rus'–Byzantine Treaties give a valuable insight into the names of the Rus'. Of the fourteen Rus' signatories to the Rus'–Byzantine Treaty in 907, all had Norse names. By the Rus'–Byzantine Treaty (945) in 945, some signatories of the Rus' had Slavic names while the vast majority had Norse names.

The Chronicle presents the following origin myth for the arrival of Rus' in the region of Novgorod: the Rus'/Varangians 'imposed tribute upon the Chuds, the Slavs, the Merians, the Ves', and the Krivichians' (a variety of Slavic and Finnic peoples).

The tributaries of the Varangians drove them back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves. There was no law among them, but tribe rose against tribe. Discord thus ensued among them, and they began to war one against the other. They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us, and judge us according to the Law". They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Russes: these particular Varangians were known as Russes, just as some are called Swedes, and others Normans, English, and Gotlanders, for they were thus named. The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichians and the Ves' then said to the people of Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us". Thus they selected three brothers, with their kinsfolk, who took with them all the Russes and migrated. The oldest, Rurik, located himself in Novgorod; the second, Sineus, at Beloozero; and the third, Truvor, in Izborsk. On account of these Varangians, the district of Novgorod became known as the land of Rus'.

From among Rurik's entourage it also introduces two Swedish merchants Askold and Dir (in the chronicle they are called "boyars", probably because of their noble class). The names Askold (Template:Lang-on) and Dir (Template:Lang-on) are Swedish; the chronicle says that these two merchants were not from the family of Rurik, but simply belonged to his retinue. Later, the Primary Chronicle claims, they conquered Kiev and created the state of Kievan Rus' (which was preceded by the Rus' Khaganate).

Arabic sources

Further information: Caspian expeditions of the Rus'

Henryk Siemiradzki (1883)

Arabic-language sources for the Rus' people are relatively numerous, with over 30 relevant passages in roughly contemporaneous sources. It can be difficult to be sure that when Arabic sources talk about Rus' they mean the same thing as modern scholars. Sometimes it seems to be a general term for Scandinavians: when Al-Yaqūbi recorded Rūs attacking Seville in 844, he was almost certainly talking about Vikings based in Frankia. At other times, it might denote people other than or alongside Scandinavians: thus the Mujmal al-Tawarikh calls the Khazars and Rus' 'brothers'; later, Muhammad al-Idrisi, Al-Qazwini, and Ibn Khaldun all identified the Rus' as a sub-group of the Turks. These uncertainties have fed into debates about the origins of the Rus'.

Arabic sources for the Rus' had been collected, edited and translated for Western scholars by the mid-20th century. However, relatively little use was made of the Arabic sources in studies of the Rus' before the 21st century. This is partly because they mostly concern the region between the Black and the Caspian Seas, and from there north along the lower Volga and the Don. This made them less relevant than the Primary Chronicle to understanding European state formation further west. Imperialist ideologies, in Russia and more widely, discouraged research emphasising an ancient or distinctive history for Inner Eurasian peoples. Arabic sources portray Rus' people fairly clearly as a raiding and trading diaspora, or as mercenaries, under the Volga Bulghars or the Khazars, rather than taking a role in state formation.

The most extensive Arabic account of the Rus' is by the Muslim diplomat and traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlan, who visited Volga Bulgaria in 922, and described people under the label Rūs/Rūsiyyah at length, beginning thus:

I have seen the Rus as they came on their merchant journeys and encamped by the Itil. I have never seen more perfect physical specimens, tall as date palms, blond and ruddy; they wear neither tunics nor caftans, but the men wear a garment which covers one side of the body and leaves a hand free. Each man has an axe, a sword, and a knife, and keeps each by him at all times. The swords are broad and grooved, of Frankish sort. Each woman wears on either breast a box of iron, silver, copper, or gold; the value of the box indicates the wealth of the husband. Each box has a ring from which depends a knife. The women wear neck-rings of gold and silver. Their most prized ornaments are green glass beads. They string them as necklaces for their women.

— Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings

Apart from Ibn Fadlan's account, scholars draw heavily on the evidence of the Persian traveler Ibn Rustah who, it is postulated, visited Novgorod (or Tmutarakan, according to George Vernadsky) and described how the Rus' exploited the Slavs.

As for the Rus, they live on an island ... that takes three days to walk round and is covered with thick undergrowth and forests; it is most unhealthy. ... They harry the Slavs, using ships to reach them; they carry them off as slaves and…sell them. They have no fields but simply live on what they get from the Slav's lands. ... When a son is born, the father will go up to the newborn baby, sword in hand; throwing it down, he says, "I shall not leave you with any property: You have only what you can provide with this weapon."

— Ibn Rustah

Byzantine sources

- Further information: Rus'–Byzantine War and Rus'–Byzantine Treaty

In his treatise De Administrando Imperio, Constantine VII describes the Rhos as the neighbours of Pechenegs who buy from the latter cows, horses, and sheep "because none of these animals may be found in Rhosia". His description represents the Rus' as a warlike northern tribe. Constantine also enumerates the names of the Dnieper cataracts in both rhosisti ('ῥωσιστί', the language of the Rus') and sklavisti ('σκλαβιοτί', the language of the Slavs). The Rus' names can most readily be etymologised as Old Norse, and have been argued to be older than the Slavic names:

Constantine's form Latin transliteration Constantine's interpretation of the Slavonic

Proposed Old Norse etymons Ἐσσονπῆ Essoupi "does not sleep" nes uppi "upper promontory" súpandi "slurping"

Οὐλβορσί Oulvorsi "island of the waterfall" Úlfarsey "Úlfar's island" hólm-foss "island rapid"

Γελανδρί Gelandri "the sound of the fall" gjallandi/gellandi "yelling, loudly ringing" Ἀειφόρ Aeifor pelicans' nesting place æ-fari/ey-færr "never passable" æ-for/ey-forr "ever fierce"

Βαρονφόρος Varouforos it forms a great maelstrom vara-foss "stony shore rapid" báru-foss "wave rapid"

Λεάντι Leanti "surge of water" hlæjandi "laughing" Στρούκουν Stroukoun "the little fall" strjúkandi "stroking, delicately touching" strukum, "rapid current"

Western European sources

The first Western European source to mention the Rus' are the Annals of St. Bertin (Annales Bertiniani). These relate that Emperor Louis the Pious' court at Ingelheim, in 839, was visited by a delegation from the Byzantine emperor. In this delegation there were two men who called themselves Rhos (Rhos vocari dicebant). Louis enquired about their origins and learnt that they were Swedes (suoni). Fearing that they were spies for their allies, the Danes, he detained them, before letting them proceed after receiving reassurances from Byzantium. Subsequently, in the 10th and 11th centuries, Latin sources routinely confused the Rus' with the extinct East Germanic tribe, the Rugians. Olga of Kiev, for instance, was designated in one manuscript as a Rugian queen.

Another source comes from Liutprand of Cremona, a 10th-century Lombard bishop who in a report from Constantinople to Holy Roman Emperor Otto I wrote, in reference to the Rhos (Rus'), 'the Russians whom we call by the other name of Norsemen'.

Archaeology

The quantity of archaeological evidence for the regions where the Rus' people were active grew steadily through the 20th century, and beyond, and the end of the Cold War made the full range of material increasingly accessible to researchers. Key excavations have included those at Staraja Ladoga, Novgorod, Rurikovo Gorodischche, Gnëzdovo, Shestovitsa, numerous settlements between the Upper Volga and the Oka. Twenty-first century research, therefore, is giving the synthesis of archaeological evidence an increasingly prominent place in understanding the Rus'. The distribution of coinage, including the early 9th-century Peterhof Hoard, has provided important ways to trace the flow and quantity of trade in areas where Rus were active, and even, through graffiti on the coins, the languages spoken by traders.

There is also a great number of Varangian runestones, where voyages to the east (Austr) are mentioned.

In the mythical lays of the Poetic Edda, after her true love Sigurd is killed, Brunhild (Brynhildr in Old Norse) has eight slave girls and five serving maids killed and then stabs herself with her sword so that she can be with him in Valhalla, as told in The Short Lay of Sigurd, similarly to the sacrifices of slave girls that Ibn Fadlan described in his eyewitness accounts of the Rus'. Swedish ship burials sometimes contain both males and females. According to the website of Arkeologerna (The Archaeologists), part of the National Historical Museums in Sweden, archaeologists have also found in an area outside of Uppsala a boat burial that contained the remains of a man, a horse and a dog, along with personal items including a sword, spear, shield, and an ornate comb. Swedish archeologists believe that during the Viking age Scandinavian human sacrifice was still common and that there were more grave offerings for the deceased in the afterlife than in earlier traditions that sacrificed human beings to the gods exclusively. The inclusion of weapons, horses and slave girls in graves also seems to have been practiced by the Rus.

References

- ^ Entry Ryssland in Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 668.

- ^ Stefan Brink, 'Who were the Vikings?', in The Viking World, ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4-10 (pp. 6-7).

- "Russ, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021.

- Entry Rodd in Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 650f.

- Blöndal, Sigfús (1978). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521035521. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Русь in "Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary" online

- ^ Entry Roslagen in Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 654.

- Entry Rospigg in Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 654f.

- Entry 2. lag in Hellquist, Elof (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok [Swedish etymological dictionary] (in Swedish). Lund: Gleerup. p. 339.

- Stefan Brink; Neil Price (31 October 2008). The Viking World. Routledge. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-134-31826-1.

- Joel Karlsson (2012) Stockholm university https://www.archaeology.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.123007.1360163562!/menu/standard/file/Karlsson_Joel_Ofria_omnamnda-pa_runstenar.pdf page 4-5

- Pritsak, Omeljan. (1981). The Origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 348. ISBN 0-674-64465-4

- Wladyslaw Duczko (1 January 2004). Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. BRILL. pp. 67–70. ISBN 90-04-13874-9.

- Gary Dean Peterson (21 June 2016). Vikings and Goths: A History of Ancient and Medieval Sweden. McFarland. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4766-2434-1.

- Gwyn Jones (2001). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-19-280134-0.

- Sverrir Jakobsson (2020). The Varangians: In God's Holy Fire. Springer Nature. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-030-53797-5.

- René Chartrand; Keith Durham; Mark Harrison; Ian Heath (22 September 2016). The Vikings. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4728-1323-7.

- Mickevičius, Arturas (30 November 1997). "Curonian "Kings" and "Kingdoms" of the Viking Age". Lithuanian Historical Studies. 2 (1): 11. doi:10.30965/25386565-00201001.

- Wladyslaw Duczko (1 January 2004). Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. BRILL. p. 10. ISBN 90-04-13874-9.

- Elizabeth Warner (1 July 2002). Russian Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-292-79158-9.

- Marika Mägi, In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication Across the Baltic Sea, The Northern World, Volume 84 (Leiden: Brill, 2018), p. 195, citing Alf Thulin, 'The Rus' of Nestor's Chronicle', Mediaeval Scandinavia, 13 (2000)

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-521-82992-5.

- Kaplan, Frederick I. (1954). "The Decline of the Khazars and the Rise of the Varangians". American Slavic and East European Review. 13 (1): 1. doi:10.2307/2492161. ISSN 1049-7544.

- Orest Subtelny (1 January 2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8020-8390-6.

- Ole Crumlin-Pedersen (31 December 2013). "Vikling Warriors and the Byzantine Empire". In Line Bjerg; John H. Lind; Soren Michael Sindbaek (eds.). From Goths to Varangians: Communication and Cultural Exchange between the Baltic and the Black Sea. Aarhus University Press. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-87-7124-425-0.

- Paul R. Magocsi (1 January 2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.

- Birgit Sawyer (2000). The Viking-age Rune-stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford University Press. pp. 116–119. ISBN 978-0-19-820643-9.

- Judith Jesch (2001). Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 86, 90, 178. ISBN 978-0-85115-826-6.

- ^ Duczko, Wladyslaw. Viking Rus : Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. The Northern World. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

- Zaliznyak, Andrey Anatolyevich. "About Russian Language History". elementy.ru. Mumi-Trol School. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Alexander Basilevsky (5 April 2016). Early Ukraine: A Military and Social History to the Mid-19th Century. McFarland. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4766-2022-0.

The main activity was the production of amber and glass beads for the fur trade where the pelts were bought from local hunters and sold to the Bulgars and Khazars for valuable silver dirhams. In fact, the Staraia Ladoga settlements were built initially as a manufacturing center and to conduct trade in the north and in the Baltic region. This is confirmed by silver dirham finds in some of the earliest log buildings constructed there

- Larsson, G. (2013) Ingvar the Fartravellers Journey: Historical and Archaeological Sources http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1257116/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Blöndal & Benedikz (2007) pp. 60–62

- DeVries (1999) pp. 29–30

- Pritsak 1981:386

- Adam (von Bremen) (1846). Adami Gesta hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum ex recensione Lappenbergii. Hahn. p. 153.

- Adam av Bremen (1984), Historien om Hamburgstiftet och dess biskopar. Stockholm: Proprius, p. 252 (Book IV, Scholion 140).

- Braun, F. & Arne, T. J. (1914). "Den svenska runstenen från ön Berezanj utanför Dneprmynningen", in Ekhoff, E. (ed.) Fornvännen årgång 9 pp. 44-48. , p. 48

- Pritsak, O. (1987). The origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 306

- Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, 'New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources', Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 10 (2014), 65–97 doi:10.1484/J.VMS.5.105213 (pp. 66-67).

- Duczko 2004, p. 210

- The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text, ed. and trans. by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Cambridge, MA: The Medieval Academy of America, 1953), ISBN 0-910956-34-0, s.aa. 6368-6370 (860-862 CE) .

- Kotlyar, M. Prinices of Kiev Kyi and Askold. Warhitory.ukrlife.org. 2002

- Serhii Plokhy (7 September 2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-139-45892-4.

- Hyun Jin Kim (18 April 2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-107-06722-6.

- Iver B. Neumann; Einar Wigen (19 July 2018). The Steppe Tradition in International Relations: Russians, Turks and European State Building 4000 BCE–2017 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-108-36891-9.

- Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, 'New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources', Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 10 (2014), 65–97 doi:10.1484/J.VMS.5.105213, p. 68.

- ^ P.B. Golden, “Rūs”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 26 July 2018 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0942.

- ^ James E. Montgomery, 'Ibn Faḍlān and the Rūsiyyah', Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 3 (2000), 1-25.

- Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 15-45 (esp. p. 31).

- Brink & Price 2008, p. 552

- Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, 'New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources', Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 10 (2014), 65–97 doi:10.1484/J.VMS.5.105213 (p. 73).

- A. Seippel (ed.), Rerum normannicarum fonts arabici, 2 vols (Oslo: Brøgger, 1896). This edition of Arabic sources for references to Vikings was translated into Norwegian, and expanded, by H. Birkeland (ed. and trans.), Nordens historie: Middlealderen etter arabiske kilder (Oslo: Dyburad, 1954). It was translated into English by Alauddin I. Samarra’i (trans.), Arabic Sources on the Norse: English Translation and Notes Based on the Texts Edited by A. Seippel in ‘Rerum Normannicarum fontes Arabici’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1959).

- James E. Montgomery, 'Ibn Rusta’s Lack of "Eloquence", the Rus, and Samanid Cosmography’, Edebiyat, 12 (2001), 73–93.

- James E. Montgomery, 'Arabic Sources on the Vikings', in The Viking World, ed. by Stefan Brink (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 550–61.

- James E. Montgomery, ‘Vikings and Rus in Arabic Sources’, in Living Islamic History, ed. by Yasir Suleiman (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), pp. 151–65.

- ^ Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, 'New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources', Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 10 (2014), 65–97 doi:10.1484/J.VMS.5.105213.

- Thorir Jonsson Hraundal, 'New Perspectives on Eastern Vikings/Rus in Arabic Sources', Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, 10 (2014), 65–97 doi:10.1484/J.VMS.5.105213 (pp. 70-78).

- Jones, Gwyn (2001). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-19-280134-1.

- Quoted from National Geographic, March 1985;

Compare:Ferguson, Robert (2009). The Hammer and the Cross: A New History of the Vikings. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141923871. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

They have no fields but simply live on what they get from the Slavs' lands.

- H. R. Ellis Davidson, The Viking Road to Byzantium (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976), p. 83.p. 83.

- Sigfús Blöndal (16 April 2007). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-521-03552-1.

- Vladimir Petrukhin (2007). "Khazaria and Rus': An examination of their historical relations". In Peter B. Golden; Haggai Ben-Shammai; András Róna-Tas (eds.). The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives. BRILL. pp. 245–246. ISBN 90-04-16042-6.

- Wladyslaw Duczko (1 January 2004). Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. BRILL. pp. 49–50. ISBN 90-04-13874-9.

- Jonathan Shepard (31 October 2008). "The Viking Rus and Byzantium". In Stefan Brink; Neil Price (eds.). The Viking World. Routledge. p. 497. ISBN 978-1-134-31826-1.

- Janet Martin (6 April 2009). "The First East Slavic State". In Abbott Gleason (ed.). A Companion to Russian History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-0842-6.

- Sigfús Blöndal (16 April 2007). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-03552-1.

- Wladyslaw Duczko, Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

- Jonathan Shepherd, 'Review Article: Back in Old Rus and the USSR: Archaeology, History and Politics', English Historical Review, vol. 131 (no. 549) (2016), 384-405 doi:10.1093/ehr/cew104.

- Sean Nowak (1998). Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions in Göttingen, 4-9 August 1995. Walter de Gruyter. p. 651. ISBN 978-3-11-015455-9.

- Carolyne Larrington, ed. (2014). "A Short Poem about Sigurd". The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-19-967534-0.

- Ninna Bengtsson. "Two rare Viking boat burials uncovered in Sweden". arkeologerna.com (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Denise Roos (2014) Människor deponerade i våtmark och grav En analys av äldre järnålderns och vikingatidens deponeringstraditioner. https://www.archaeology.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.208758.1414677865!/menu/standard/file/Roos_Denise_Manniskor_deponerade_i_vatmark_och_grav.pdf page 23

- Shephard, pp. 122–3

Bibliography

- The Annals of Saint-Bertin, transl. Janet L. Nelson, Ninth-Century Histories 1 (Manchester and New York, 1991).

- Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Bury, John Bagnell; Gwatkin, Henry Melvill (1936). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 3. University Press. ISBN 0415327563.

- Christian, David. A History of Russia, Mongolia, and Central Asia. Blackwell, 1999.

- Danylenko, Andrii. "The name Rus': In search of a new dimension." Jahrbueher fuer Geschichte Osteuropas 52 (2004), 1–32.

- Davidson, H.R. Ellis, The Viking Road to Byzantium. Allen & Unwin, 1976.

- Dolukhanov, Pavel M. The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. New York: Longman, 1996.

- Duczko, Wladyslaw. Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe (The Northern World; 12). Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 90-04-13874-9).

- Goehrke, C. Frühzeit des Ostslaven. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1992.

- Magocsi, Paul R. A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996.

- Pritsak, Omeljan. The Origin of Rus'. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Stang, Hakon. The Naming of Russia. Oslo: Middelelser, 1996.

- Gerard Miller as the author of the Normanist theory (Brockhaus and Efron)

- Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415327563.

- On the language of old Rus: some questions and suggestions. Horace Gray Lunt. Harvard University, Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 1975

- The Emergence of Rus: 750–1200. Simon Franklin, Jonathan Shephard. Longman Publishing Group, 1996

- The Origin of Rus'. Omeljan Pritsak. Harvard University Press, 1981

- The Primary Chronicle's 'Ethnography' Revisited: Slavs and Varangians in the Middle Dnieper Region and the Origin of the Rus' State. Olksiy P Tolochko; in Franks, Northmen and Slavs. Identities and State Formation in Early Medieval Europe. Editors: Ildar H. Garipzanov, Patrick J. Geary, and Przemysław Urbańczyk. Brepols, 2008.

- Brink, Stefan; Price, Price (2008). The Viking World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134318261. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Duczko, Wladyslaw (2004). Viking Rus: Studies on the Presence of Scandinavians in Eastern Europe. Brill. ISBN 9004138749. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2005). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181.

External links

Media related to Rus' people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rus' people at Wikimedia Commons- James E. Montgomery, 'Ibn Faḍlān and the Rūsiyyah', Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 3 (2000), 1-25. Archive.org. Includes a translation of Ibn Fadlān's discussion of the Rūs/Rūsiyyah.

Categories: