| Revision as of 17:23, 21 November 2022 editFemke (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators21,026 edits Simplified the second sentence, we don't need to explain the physics of climate changeTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:36, 21 November 2022 edit undoEMsmile (talk | contribs)Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users60,023 edits →Funding: removed excerpt as per talk page suggestion. The article on climate finance is not very good yet.Tag: 2017 wikitext editorNext edit → | ||

| Line 408: | Line 408: | ||

| Funding, such as the ], is often provided by nations, groups of nations and increasingly NGO and private sources. These funds are often channelled through the ] (GEF). This is an environmental funding mechanism in the World Bank which is designed to deal with global environmental issues.<ref name="Evans">Evans. J (forthcoming 2012) Environmental Governance, Routledge, Oxon</ref> The GEF was originally designed to tackle four main areas: biological diversity, climate change, international waters and ozone layer depletion, to which ] and ] were added. The GEF funds projects that are agreed to achieve global environmental benefits that are endorsed by governments and screened by one of the GEF's implementing agencies.<ref>Mee. L. D, Dublin. H. T, Eberhard. A. A (2008) Evaluating the Global Environment Facility: A goodwill gesture or a serious attempt to deliver global benefits?, Global Environmental Change 18, 800–810</ref> | Funding, such as the ], is often provided by nations, groups of nations and increasingly NGO and private sources. These funds are often channelled through the ] (GEF). This is an environmental funding mechanism in the World Bank which is designed to deal with global environmental issues.<ref name="Evans">Evans. J (forthcoming 2012) Environmental Governance, Routledge, Oxon</ref> The GEF was originally designed to tackle four main areas: biological diversity, climate change, international waters and ozone layer depletion, to which ] and ] were added. The GEF funds projects that are agreed to achieve global environmental benefits that are endorsed by governments and screened by one of the GEF's implementing agencies.<ref>Mee. L. D, Dublin. H. T, Eberhard. A. A (2008) Evaluating the Global Environment Facility: A goodwill gesture or a serious attempt to deliver global benefits?, Global Environmental Change 18, 800–810</ref> | ||

| {{excerpt|Climate finance|paragraphs=1-2|file=no}} | |||

| ===Economics=== | ===Economics=== | ||

Revision as of 17:36, 21 November 2022

Actions to limit the effects of climate changeClimate change mitigation consists of human actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or to enhance carbon sinks that absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. As such, mitigation limits the amount of global warming. The combustion of fossil fuels can be reduced by switching to clean energy and through energy conservation. Examples of climate change mitigation policies include carbon pricing by carbon taxes and carbon emission trading, easing regulations for renewable energy deployment, reductions of fossil fuel subsidies and divestment from fossil fuel finance and subsidies for clean energy.

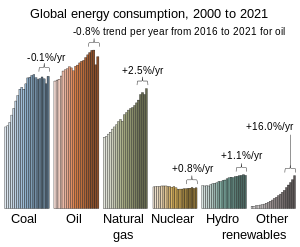

The use of coal, oil and gas for energy (73% of total emissions), agriculture and land use (16%), other industrial practices (5%), waste management (3%) and deforestation (2%) increase the concentration of greenhouse gases, notably carbon dioxide and methane. Solar and wind energy are increasingly becoming cheaper than fossil fuels for electricity production. Their variability can be addressed by energy storage and improved electrical grids. This includes long-distance electricity transmission, demand management and diversification of renewables. As low-emission energy is deployed at large scale, transport and heating can shift to these mostly electric sources. This includes heat pumps and electric vehicles which are by far more energy efficient. Natural gas with carbon capture and storage is debated as an option for industrial processes where fossil combustion cannot be avoided.

Methane is the second most relevant greenhouse gas with high short-term impact. Most of it is released during fossil fuel production and by agriculture. This can be targeted by reductions in dairy products and meat consumption. In addition, various natural processes and technologies can be used for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) from the atmosphere. These include afforestation, reforestation, carbon sequestration and direct air capture.

Current policies are estimated to produce global warming of about 2.7 °C by 2100. This is significantly above the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 °C and preferably to 1.5 °C as per the Paris Agreement.

Overview

Definition

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report defines climate change mitigation as "A human intervention to reduce emissions or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases".

Goals

The overall goal of climate change mitigation is: "to preserve a biosphere which can sustain human civilization and the complex of ecosystem services which surround and support it. This means reducing anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions towards net zero to limit the warming, with global goals agreed in the Paris Agreement."

Co-benefits

There are also co-benefits of climate change mitigation. For example, in the transport sector, possible co-benefits of mitigation strategies include: air quality improvements, health benefits, equitable access to transportation services, reduced traffic congestion, and reduced material demand. The increased use of green and blue infrastructure can reduce the urban heat island effect and heat stress on people, which will improve the mental and physical health of urban dwellers. Climate change mitigation might also lead to less inequality and poverty.

Risks and negative side effects

Impacts of mitigation measures can also have negative side effects. This is highly context-specific and can also depend on the scale of the intervention. In agriculture and forestry, mitigation measures can affect biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. In the area of renewable energies, mining for metals and minerals can increase threats to conservation areas. To address one of these issues, there is research into ways to recycle solar panels and electronic waste in order to create a source for materials that would otherwise need to be mined.

Discussions about risks and negative side effects of mitigation measures can "lead to deadlock or a sense that there are intractable obstacles to taking action".

Approaches

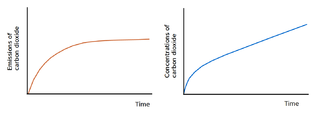

If CO2 emissions would only stop growing this would not stabilize the GHG concentration in the atmosphere.

If CO2 emissions would only stop growing this would not stabilize the GHG concentration in the atmosphere. Stabilizing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 at a constant level would require emissions to be effectively eliminated.

Stabilizing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 at a constant level would require emissions to be effectively eliminated.

Climate change mitigation is all about reducing and recapturing greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse gases are primarily carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases.

The approaches that are being used fall into the following categories:

- Clean energy: sustainable energy and sustainable transport

- Energy conservation: efficient energy use and energy conservation

- Agriculture and industry: sustainable agriculture and green industrial policy

- Carbon sequestration: carbon dioxide removal and carbon sequestration

Climate change can be mitigated by reducing the rate at which greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere, and by increasing the rate at which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere. To limit global warming to less than 1.5 °C global greenhouse gas emissions needs to be net-zero by 2050, or by 2070 with a 2 °C target. This requires far-reaching, systemic changes on an unprecedented scale in energy, land, cities, transport, buildings, and industry.

The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that countries need to triple their pledges under the Paris Agreement within the next decade to limit global warming to 2 °C. An even greater level of reduction is required to meet the 1.5 °C goal. With pledges made under the Paris Agreement as of 2024, there would be a 66% chance that global warming is kept under 2.8 °C by the end of the century (range: 1.9–3.7 °C, depending on exact implementation and technological progress). When only considering current policies, this raises to 3.1 °C. Globally, limiting warming to 2 °C may result in higher economic benefits than economic costs.

Although there is no single pathway to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 °C, most scenarios and strategies see a major increase in the use of renewable energy in combination with increased energy efficiency measures to generate the needed greenhouse gas reductions. To reduce pressures on ecosystems and enhance their carbon sequestration capabilities, changes would also be necessary in agriculture and forestry, such as preventing deforestation and restoring natural ecosystems by reforestation.

Other approaches to mitigating climate change have a higher level of risk. Scenarios that limit global warming to 1.5 °C typically project the large-scale use of carbon dioxide removal methods over the 21st century. There are concerns, though, about over-reliance on these technologies, and environmental impacts. Solar radiation modification (SRM) is under discussion as a possible supplement to reductions in emissions. However, SRM raises significant ethical and global governance concerns, and its risks are not well understood.Timescales

Tools for mitigation vary in the timescales needed for them to have an impact on emissions. For example, solar power is a mature technology that can be rapidly implemented, which allows coal-fired powers plant to be retired (or not built in the first place). The mitigation tools that can yield the most emissions reductions in the short time remaining before 2030 are solar energy, reduced conversion of forests and other ecosystems, wind energy, carbon sequestration in agriculture, followed by the group of ecosystem restoration, afforestation, and reforestation. Elimination of certain other sources of emissions will require research, technology development, and conversion or replacement of facilities, and therefore will take much longer.

Greenhouse gas emissions

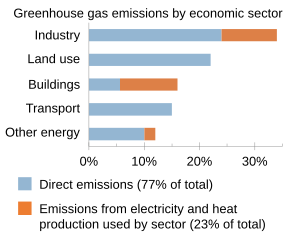

Accounting of greenhouse gas emissions by sector can be done in different ways. An established method by Our World in Data groups them as follows (data for 2016): Energy (electricity, heat and transport): 73.2%, direct industrial processes: 5.2%, waste: 3.2%, agriculture, forestry and land use: 18.4%.

This section is an excerpt from Greenhouse gas emissions.Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities intensify the greenhouse effect. This contributes to climate change. Carbon dioxide (CO2), from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, is the main cause of climate change. The largest annual emissions are from China followed by the United States. The United States has higher emissions per capita. The main producers fueling the emissions globally are large oil and gas companies. Emissions from human activities have increased atmospheric carbon dioxide by about 50% over pre-industrial levels. The growing levels of emissions have varied, but have been consistent among all greenhouse gases. Emissions in the 2010s averaged 56 billion tons a year, higher than any decade before. Total cumulative emissions from 1870 to 2022 were 703 GtC (2575 GtCO2), of which 484±20 GtC (1773±73 GtCO2) from fossil fuels and industry, and 219±60 GtC (802±220 GtCO2) from land use change. Land-use change, such as deforestation, caused about 31% of cumulative emissions over 1870–2022, coal 32%, oil 24%, and gas 10%.

Carbon dioxide is the main greenhouse gas resulting from human activities. It accounts for more than half of warming. Methane (CH4) emissions have almost the same short-term impact. Nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases (F-gases) play a lesser role in comparison. Emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide in 2023 were all higher than ever before.

Electricity generation, heat and transport are major emitters; overall energy is responsible for around 73% of emissions. Deforestation and other changes in land use also emit carbon dioxide and methane. The largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions is agriculture, closely followed by gas venting and fugitive emissions from the fossil-fuel industry. The largest agricultural methane source is livestock. Agricultural soils emit nitrous oxide partly due to fertilizers. Similarly, fluorinated gases from refrigerants play an outsized role in total human emissions.By type of greenhouse gas

Main article: Greenhouse gas emissions § Emissions by greenhouse gasCarbon dioxide (CO2) is the dominant emitted greenhouse gas, while methane (CH4) emissions almost have the same short-term impact. Nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases (F-Gases) play a minor role.

Methane emissions come from agriculture, closely followed by gas venting and fugitive emissions from the fossil-fuel industry. The largest agricultural methane source is livestock. Livestock and manure are 5.8% of all GHG emissions, although this depends on the time horizon used for the global warming potential of the respective gas. It can be reduced by reductions in dairy products and meat consumption.

GHG emissions are measured in CO2 equivalents determined by their global warming potential (GWP), which depends on their lifetime in the atmosphere. There are widely-used greenhouse gas accounting methods that convert volumes of methane, nitrous oxide and other greenhouse gases to carbon dioxide equivalents. Estimations largely depend on the ability of oceans and land sinks to absorb these gases. Short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) including methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), tropospheric ozone and black carbon persist in the atmosphere for a period ranging from days to 15 years; whereas carbon dioxide can remain in the atmosphere for millennia.

Needed emissions cuts

If emissions remain on the current level of 42 GtCO2, the carbon budget for 1.5 °C could be exhausted in 2028.

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Sixth Assessment Report on climate change, warning that greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2025 at the latest and decline 43% by 2030, in order to likely limit global warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F). Secretary-general of the United Nations, António Guterres, clarified that for this "Main emitters must drastically cut emissions starting this year".

In 2019, the emissions gap report of the United Nations Environment Programme for limiting warming to 1.5 °C GHG said that emissions should be cut from the level of 2020 by 76% by 2030.

In 2018, the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C said that limiting warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) would require decreasing net CO2 emissions by around 45% by 2030 from the level of 2010 and reach net zero by 2050. For limiting global warming to below 2 °C (3.6 °F), CO2 emissions should decline by 25% by 2030 and by 100% by 2075. Non-CO2 emissions need to be strongly reduced at similar levels in both scenarios.

Emissions and economic growth

Economic growth is a key driver of CO2 emissions. As the economy expands, demand for energy and energy-intensive goods increases, pushing up CO2 emissions. On the other hand, economic growth may drive technological change and increase energy efficiency. Economic growth may be associated with specialization in certain economic sectors. If specialization is in energy-intensive sectors, specifically carbon energy sources, then there will be a strong link between economic growth and emissions growth. If specialization is in less energy-intensive sectors, e.g. the services sector, then there might be a weak link between economic growth and emissions growth.

Much of the literature focuses on the "environmental Kuznets curve" (EKC) hypothesis, which posits that at early stages of development, pollution per capita and GDP per capita move in the same direction. Beyond a certain income level, emissions per capita will decrease as GDP per capita increase, thus generating an inverted-U shaped relationship between GDP per capita and pollution. However, the econometrics literature did not support either an optimistic interpretation of the EKC hypothesis – i.e., that the problem of emissions growth will solve itself – or a pessimistic interpretation – i.e., that economic growth is irrevocably linked to emissions growth. Instead, it was suggested that there was some degree of flexibility between economic growth and emissions growth.

Energy systems

Main articles: Energy system, Energy transition, Low-carbon economy, and Fossil fuel phase-out

The energy system, which includes the use and delivery of energy, is the main emitter of CO2. Reducing energy sector emissions is therefore essential to limit warming. Rapid and deep reductions in the CO2 and GHG emissions from energy system are needed to limit global warming to well below 2 °C. Recommended measures includes: "reduced fossil fuel consumption, increased production from low- and zero carbon energy sources, and increased use of electricity and alternative energy carriers".

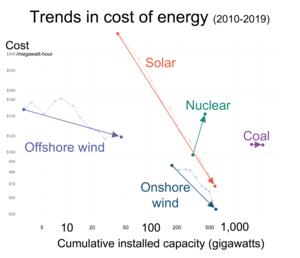

The competitiveness of renewable energy is a key to a rapid deployment. In 2020, onshore wind and solar photovoltaics were the cheapest source for new bulk electricity generation in many regions. Storage requirements cause additional costs. A carbon price can increase the competitiveness of renewable energy.

Low-carbon energy sources

Main article: Renewable energy See also: Low-carbon economy, Renewable energy commercialization, and Renewable energy debateWind and sun can be sources for large amounts of low-carbon energy at competitive production costs. But even in combination, generation of variable renewable energy fluctuates a lot. This can be tackled by extending grids over large areas with a sufficient capacity or by using energy storage (see also: forms of grid energy storage) and by other means. Load management of industrial energy consumption can help to balance the production of renewable energy production and its demand. Electricity production by biogas and hydro power can follow the energy demand. Both can be driven by variable energy prices.

The deployment of renewable energy would have to be accelerated six-fold though to stay under the 2 °C target.

Solar energy

Main article: Solar energy

- Solar photovoltaics (PV) has become the cheapest way to produce electric energy in many regions of the world. The growth of photovoltaics is exponential and has doubled every three years since the 1990s. In the summer, PV power generation follows the daily demand curve. New trends are floating solar and agrivoltaics.

- A different technology is concentrated solar power (CSP) using mirrors or lenses to concentrate a large area of sunlight onto a receiver. With CSP, the energy can be stored for a few hours, providing supply in the evening. This can outweigh the higher costs compared to PV.

- Solar water heating has doubled between 2010 and 2019. Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collectors combine PV and solar heating.

Wind power

Main article: Wind power

Regions in the higher northern and southern latitudes have the highest potential for wind power. Offshore wind power currently has a share of about 10% of new installations. Offshore wind farms are more expensive but the units deliver more energy per installed capacity with less fluctuations. In most regions, wind power generation is higher in the winter when PV output is low. For this reason, combinations of wind and solar power are recommended.

Hydro power

Main article: Hydropower

Hydroelectricity plays a leading role in countries like Brazil, Norway and China. but there are geographical limits and environmental issues. Tidal power can be used in coastal regions.

Bioenergy

Main article: BiomassBiogas plants can provide dispatchable electricity generation, and heat when needed. A common concept is the co-fermentation of energy crops mixed with manure in agriculture. Burning plant-derived biomass releases CO2, but it has still been classified as a renewable energy source in the EU and UN legal frameworks because photosynthesis cycles the CO2 back into new crops. How a fuel is produced, transported and processed has a significant impact on lifecycle emissions. Renewable biofuels are starting to be used in aviation.

Other low-carbon energy sources

Nuclear power

Main article: Nuclear power

In most 1.5 °C pathways of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C the share of nuclear power is increased. The main advantage of nuclear energy is the ability to deliver large amounts of base load when renewable energy is not available.

On the other hand, environmental and security risks could outweigh the benefits. As of 2019, no country has found a final solution to nuclear waste which can cause future damage and costs over more than one million years. Separated plutonium and enriched uranium could be used for nuclear weapons, which is considered to be a strategical motivation for countries to promote nuclear power. The according risks are comparable to climate change. The Fukushima disaster is estimated to cost taxpayers ~$187 billion and radioactive waste management is estimated to cost the EU ~$250 billion by 2050.

The construction of new nuclear reactors currently takes about 10 years, substantially longer than scaling up the deployment of wind and solar. The largest drawback of nuclear energy is often considered to be the large construction and operating costs when compared to alternatives of sustainable energy sources whose costs are decreasing and which are the fastest-growing source of electricity generation. Nuclear power avoided 2–3% of total global GHG emissions in 2021. China is building a significant number of new power plants, albeit significantly fewer reactors than originally planned. As of 2019 the cost of extending nuclear power plant lifetimes is competitive with other electricity generation technologies, including new solar and wind projects. New projects are reported to be highly dependent on public subsidies.

Nuclear fusion research, in the form of the ITER and other experimental projects, is underway but fusion energy is not likely to be commercially widespread before 2050.

Natural gas for fossil fuel switching

This section is an excerpt from Sustainable energy § Fossil fuel switching and mitigation.Switching from coal to natural gas has advantages in terms of sustainability. For a given unit of energy produced, the life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of natural gas are around 40 times the emissions of wind or nuclear energy but are much less than coal. Burning natural gas produces around half the emissions of coal when used to generate electricity and around two-thirds the emissions of coal when used to produce heat. Natural gas combustion also produces less air pollution than coal. However, natural gas is a potent greenhouse gas in itself, and leaks during extraction and transportation can negate the advantages of switching away from coal. The technology to curb methane leaks is widely available but it is not always used.

Switching from coal to natural gas reduces emissions in the short term and thus contributes to climate change mitigation. However, in the long term it does not provide a path to net-zero emissions. Developing natural gas infrastructure risks carbon lock-in and stranded assets, where new fossil infrastructure either commits to decades of carbon emissions, or has to be written off before it makes a profit.Energy storage

Main article: Energy storage See also: Hydrogen economyWind energy and photovoltaics can deliver large amounts of electric energy but not at any time and place. One approach is the conversation into storable forms of energy. This generally leads to losses in efficiency.

For storage requirements up to a few days, pumped hydro (PHES), compressed air (CAES) and Li-on batteries are most cost effective depending on charging rhythm. For 2040, a more significant role for Li-on and hydrogen is projected. Li-on batteries]] are widely used in battery storage power stations and are starting to be used in vehicle-to-grid storage. They provide a sufficient round-trip efficiency of 75–90 %. Their production can cause environmental problems. Levelized costs for battery storage have drastically fallen to 0.15 US$/KWh

Hydrogen may be useful for seasonal energy storage. The low efficiency of 30% of the reconversion to electricity must improve dramatically before hydrogen storage can offer the same overall energy efficiency as batteries. Thermal energy in the conversion process can be used for district heating. The concept of solar hydrogen is discussed for remote desert projects where grid connections to demand centers are not available. Because it has more energy per unit volume sometimes it may be better to use hydrogen in ammonia.

Super grids

Main article: Super grid

Long-distance power lines help to minimize storage requirements. A continental transmission network can smoothen local variations of wind energy. With a global grid, even photovoltaics could be available all day and night. The strongest high-voltage direct current (HVDC) connections are quoted with losses of only 1.6% per 1000 km with a clear advantage compared to AC. HVDC is currently only used for point-to-point connections. Meshed HVDC grids may be used to connect offshore wind in future.

China has built many HVDC connections within the country and supports the idea of a global, intercontinental grid as a backbone system for the existing national AC grids. A super grid in the US in combination with renewable energy could reduce GHG emissions by 80%.

Smart grid and load management

Main articles: Smart grid and Load managementInstead of expanding grids and storage for more power, electricity demand can be adjusted on the consumer side. This can flatten demand peaks. Traditionally, the energy system has treated consumer demand as fixed. Instead, data systems can combine with advanced software to pro-actively manage demand and respond to energy market prices.

Time of use tariffs are a common way to motivate electricity users to reduce their peak load consumption. On a household level, charging electric vehicles or running heat pumps combined with hot water storage when wind or sun energy are available reduces electricity costs.

Dynamic demand plans have devices passively shut off when stress is sensed on the electrical grid. This method may work very well with thermostats, when power on the grid sags a small amount, a low power temperature setting is automatically selected reducing the load on the grid. Refrigerators or heat pumps can reduce their consumption when clouds pass over solar installations. Consumers need to have a smart meter in order for the utility to calculate credits. Smart Scheduling of activities and processes can adjust demand to fluctuating supply.

Demand response devices can receive all sorts of messages from the grid. The message could be a request to use a low power mode similar to dynamic demand, to shut off entirely during a sudden failure on the grid, or notifications about the current and expected prices for power. This allows electric cars to recharge at the least expensive rates independent of the time of day. Vehicle-to-grid uses a car's battery to supply the grid temporarily. Smart grids could also monitor/control residential devices that are noncritical during periods of peak power consumption, and return their function during nonpeak hours.

Further flexibility techniques by which smart grids can help manage the variability of renewable energy (VRE) and increase efficiency include VRE forecasting methodologies.

Energy conservation and efficiency

Main articles: Efficient energy use and Energy conservation

Global primary energy demand exceeded 161,000 TWh in 2018. This refers to electricity, transport and heating including all losses. In transport and electricity production, fossil fuel usage has a low efficiency of less than 50%. Large amounts of heat in power plants and in motors of vehicles are wasted. The actual amount of energy consumed is significantly lower at 116,000 TWh.

Service labels like Energy Star provide information on the energy consumption of products. A procurement toolkit to assist individuals and businesses buy energy efficient products that use low GWP refrigerants was developed by the Sustainable Purchasing Leadership Council. A trial of estimated financial energy cost of refrigerators alongside EU energy-efficiency class (EEEC) labels online found that the approach of labels involves a trade-off between financial considerations and higher cost requirements in effort or time for the product-selection from the many available options – which are often unlabelled and don't have any EEEC-requirement for being bought, used or sold within the EU. Moreover, in this one trial the labeling was ineffective in shifting purchases towards more sustainable options. Beyond establishing higher efficiency of household appliances such as fridges and washing machines (or smaller ovens and non-use of drying machines), facilitating (less or) greener travel, installation of heat pumps, energy audits, and reducing room heating are also important. Energy efficiency of appliances as well as cooking techniques/choices have a substantial impact on GHGs from foods. In order for consumers to efficiently conserve energy, they – especially tenants – may need to have access to the (up to real-time) data of their electricity use and knowledge about efficient conservation options. Moreover, the most effective energy conservation options may not be in households but the industry or e.g. public venues.

The cogeneration of electric energy and district heat also improves efficiency.

Head of the IEA declared the failure by governments and businesses to accelerate energy efficiency efforts as "inexplicable", with IEA analysis showing that greater efficiency could be achieved with existing technologies and measures.

Preserving and enhancing carbon sinks

Terminology

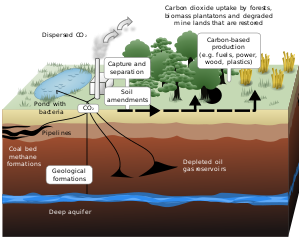

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is defined as "Anthropogenic activities removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and durably storing it in geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs, or in products. It includes existing and potential anthropogenic enhancement of biological or geochemical CO2 sinks and direct air carbon dioxide capture and storage (DACCS), but excludes natural CO2 uptake not directly caused by human activities."

The terminology in this area is still evolving. The term “geoengineering” (or climate engineering) is sometimes used in the scientific literature for both CDR (carbon dioxide removal) or SRM (solar radiation management or solar geoengineering), if the techniques are used at a global scale. The terms geoengineering or climate engineering are no longer used in IPCC reports.

Land-based mitigation options are referred to as "AFOLU mitigation options" in the 2022 IPCC report on mitigation. The abbreviation stands for "agriculture, forestry and other land use" The report described the economic mitigation potential from relevant activities around forests and ecosystems as follows: "the conservation, improved management, and restoration of forests and other ecosystems (coastal wetlands, peatlands, savannas and grasslands)". A high mitigation potential is found for reducing deforestation in tropical regions. The economic potential of these activities has been estimated to be 4.2 to 7.4 Giga tons of CO2 equivalents per year.

Globally, protecting healthy soils and restoring the soil carbon sponge could remove 7.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere annually, which is more than the annual emissions of the US. Trees capture CO2 while growing above ground and exuding larger amounts of carbon below ground. Trees contribute to the building of a soil carbon sponge. The carbon formed above ground is released as CO2 immediately when wood is burned. If dead wood remains untouched, only some of the carbon returns to the atmosphere as decomposition proceeds.

Conservation of forests

Main articles: Deforestation § Control, and Desertification § Countermeasures

Avoided deforestation reduces CO2 emissions at a rate of 1 tonne of CO2 per $1–5 in opportunity costs from lost agriculture. 95% of deforestation occurs in the tropics, where it is mostly driven by the clearing of land for agriculture.

Transferring rights over land from public domain to its indigenous inhabitants, who have had a stake for millennia in preserving the forests that they depend on, is argued to be a cost-effective strategy to conserve forests. This includes the protection of such rights entitled in existing laws, such as the Forest Rights Act in India, where concessions to land continue to go mostly to powerful companies. The transferring of such rights in China, perhaps the largest land reform in modern times, has been argued to have increased forest cover. Granting title of the land has shown to have two or three times less clearing than even state run parks, notably in the Brazilian Amazon. Even while the largest cause of deforestation in the world's second largest rainforest in the Congo is smallholder agriculture and charcoal production, areas with community concessions have significantly less deforestation as communities are incentivized to manage the land sustainably, even reducing poverty. Conservation methods that exclude humans, called "fortress conservation", and even evict inhabitants from protected areas often lead to more exploitation of the land as the native inhabitants then turn to work for extractive companies to survive.

Afforestation

Main article: Afforestation Further information: Carbon sequestration § ForestryAfforestation is the establishment of trees where there was previously no tree cover. Scenarios for new plantations covering up to 4000 Mha (6300 x 6300 km) calculate with a cumulative physical carbon biosequestration of more than 900 GtC (2300 GtCO2) until 2100. However, these are not considered a viable alternative to aggressive emissions reduction, as the plantations would need to be so large, they would eliminate most natural ecosystems or reduce food production. One example is the Trillion Tree Campaign.

Restoration of forests

Main articles: Reforestation § For climate change mitigation, Forest restoration, and Proforestation

Reforestation is the restocking of existing depleted forests or where there was once recently forests. Reforestation could save at least 1 GtCO2/year, at an estimated cost of $5–15/tCO2. Restoring all degraded forests all over the world could capture about 205 GtC (750 GtCO2). W ith increased intensive agriculture and urbanization, there is an increase in the amount of abandoned farmland. By some estimates, for every acre of original old-growth forest cut down, more than 50 acres of new secondary forests are growing. Promoting regrowth on abandoned farmland could offset years of carbon emissions.

Planting new trees can be expensive, especially for the poor who often live in areas of deforestation, and can be a risky investment as, for example, studies in the Sahel have found that 80 percent of planted trees die within two years. Instead, helping native species sprout naturally is much cheaper and more likely to survive, with even long deforested areas still containing an "underground forest" of living roots and tree stumps that are still able to regenerate. This could include pruning and coppicing the tree to accelerate its growth and that also provides woodfuel, a major source of deforestation. Such practices, called farmer-managed natural regeneration, are centuries old but the biggest obstacle towards implementing natural regrowth of trees are legal ownership of the trees by the state, often as a way of selling such timber rights to business people, leading to seedlings being uprooted by locals who saw them as a liability. Legal aid for locals and pressure to change the law such as in Mali and Niger where ownership of trees to residents was allowed has led to what has been called the largest positive environmental transformation in Africa, with it being possible to discern from space the border between Niger and the more barren land in Nigeria, where the law has not changed.

Proforestation is promoting forests to capture their full ecological potential. Secondary forests that have regrown in abandoned farmland are found to have less biodiversity than the original old-growth forests and original forests store 60% more carbon than these new forests.

Wetlands

Wet areas such as swamps and peatlands have lower oxygen levels dissolved than in the air and so oxygen reliant decomposition of organic matter by microbes into CO2 is decreased. Peatland globally covers just 3% of the land's surface but stores up to 550 gigatonnes of carbon, representing 42% of all soil carbon and exceeds the carbon stored in all other vegetation types, including the world's forests. The threat to peatlands include draining the areas for agriculture and cutting down trees for lumber as the trees help hold and fix the peatland. Additionally, peat is often sold for compost. Restoration of degraded peatlands can be done by blocking drainage channels in the peatland, and allowing natural vegetation to recover.

Coastal wetlands

Mangroves, salt marshes and seagrasses make up the majority of the ocean's vegetated habitats but only equal 0.05% of the plant biomass on land and stash carbon 40 times faster than tropical forests. Bottom trawling, dredging for coastal development and fertilizer runoff have damaged coastal habitats. Notably, 85% of oyster reefs globally have been removed in the last two centuries. Oyster reefs clean the water and make other species thrive, thus increasing biomass in that area. In addition, oyster reefs mitigate the effects of climate change by reducing the force of waves from hurricanes and reduce the erosion from rising sea levels.

Preventing permafrost leaks

The global warming induced thawing of the permafrost, which stores about two times the amount of the carbon currently released in the atmosphere, releases the potent greenhouse gas, methane, in a positive feedback cycle that is feared to lead to a tipping point called runaway climate change. While the permafrost is about 14 degrees Fahrenheit (−10 °C), a blanket of snow insulates it from the colder air above which could be 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit (−40 °C). A method proposed to prevent such a scenario is to bring back large herbivores such as seen in Pleistocene Park, where they keep the ground cooler by reducing snow cover height by about half and eliminating shrubs and thus keeping the ground more exposed to the cold air, although these proposals have also been criticized as likely to be ineffective.

Ocean-based options

Main articles: Ocean acidification § Technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the ocean, Blue carbon, and Ocean storage of carbon dioxideIn principle, carbon can be stored in ocean reservoirs. This can be done with "ocean-based mitigation systems" including ocean fertilization, ocean alkalinity enhancement or enhanced weathering. Blue carbon management is partly an ocean-based method and partly a land-based method. Most of these options could also help to reduce ocean acidification which is the drop in pH value caused by increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

The current assessment of potential for ocean-based mitigation options is in 2022 that they have only "limited current deployment", but "moderate to large future mitigation potentials" in future.

In total, "ocean-based methods have a combined potential to remove 1–100 gigatons of CO2 per year". Their costs are in the order of USD40–500 per ton of CO2. For example, enhanced weathering could remove 2–4 gigatons of CO2 per year. This technology comes with a cost of 50-200 USD per ton of CO2.

Enhanced weathering

Main article: Enhanced weatheringEnhanced weathering is a process that aims to accelerate the natural weathering by spreading finely ground silicate rock, such as basalt, onto surfaces which speeds up chemical reactions between rocks, water, and air. It removes removes carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, permanently storing it in solid carbonate minerals or ocean alkalinity. The latter also slows ocean acidification.

Engineering based methods of removing carbon dioxide

Direct air capture

Main article: Direct air captureDirect air capture is a process of capturing CO2 directly from the ambient air (as opposed to capturing from point sources) and generating a concentrated stream of CO2 for sequestration or utilization or production of carbon-neutral fuel and windgas. Artificial processes vary, and concerns have been expressed about the long-term effects of some of these processes.

Carbon capture and storage

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a method to mitigate climate change by capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from large point sources, such as cement factories or biomass power plants, and subsequently storing it away safely instead of releasing it into the atmosphere. The IPCC estimates that the costs of halting global warming would double without CCS. Norway's Sleipner gas field, beginning in 1996, stores almost a million tons of CO2 a year to avoid penalties in producing natural gas with unusually high levels of CO2.

Sectors of GHG emissions

Buildings

Main article: Energy-efficient buildingsThe buildings sector accounts for 23% of global energy-related CO2 emissions About half of the energy is used for space and water heating. Building insulation can reduce the primary energy demand significantly. Electrifying heating and cooling loads may also provide a flexible resource that can participate in demand response to integrate variable renewable resources into the grid. Solar water heating uses the thermal energy directly.

Building design and insulation

Main articles: Sustainable architecture and Green buildingSufficiency measures include moving to smaller houses when the needs of households change, mixed use of spaces and the collective use of devices. New buildings can be constructed using passive solar building design, low-energy building, or zero-energy building techniques. Existing buildings can be made more efficient through the use of insulation, high-efficiency appliances (particularly hot water heaters and furnaces), double- or triple-glazed gas-filled windows, external window shades, and building orientation and siting. In addition to designing buildings which are more energy-efficient to heat, it is possible to design buildings that are more energy-efficient to cool by using lighter-coloured, more reflective materials in the development of urban areas.

Heat pumps

See also: renewable heat

A modern heat pump typically produces around two to six times more thermal energy than electrical energy consumed, giving an effective efficiency of 200 to 600%, depending on the coefficient of performance and the outside temperature. It uses an electrically driven compressor to operate a refrigeration cycle that extracts heat energy from outdoor air or ground sources and moves that heat to the space to be warmed. In the summer months, the cycle can be reversed for air conditioning.

Electric resistant heating

Radiant heaters in households are cheap and widespread but less efficient than heat pumps. In areas like Norway, Brazil, and Quebec that have abundant hydroelectricity, electric heat and hot water are common. Large scale hot water tanks can be used for demand-side management and store variable renewable energy over hours or days.

Cooling

See also: Passive cooling and Passive daytime radiative coolingRefrigeration and air conditioning account for about 10% of global CO2 emissions caused by fossil fuel-based energy production and the use of fluorinated gases. Alternative cooling systems, such as passive cooling building design and installing passive daytime radiative cooling surfaces, can reduce air conditioning use. Suburbs and cities in hot and arid climates can significantly reduce energy consumption from cooling with daytime radiative cooling.

The energy consumption for cooling is expected to rise significantly due to increasing heat and availability of devices in poorer countries. Of the 2.8 billion people living in the hottest parts of the world, only 8% currently have air conditioners, compared with 90% of people in the US and Japan. By combining energy efficiency improvements with the transition away from super-polluting refrigerants, the world could avoid cumulative greenhouse gas emissions of up to 210–460 GtCO2e over the next four decades. A shift to renewable energy in the cooling sector comes with two advantages: Solar energy production with mid-day peaks corresponds with the load required for cooling. Additionally, cooling has a large potential for load management in the electric grid.

Transport

Main articles: Greenhouse gas emissions, Sustainable transport, and Green transportTransportation emissions account for 15% of emissions worldwide. Increasing the use of public transport, low-carbon freight transport and cycling are important components of transport decarbonization.

Electric vehicles and environmentally friendly rail help to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels. In most cases, electric trains are more efficient than air transport and truck transport. Other efficiency means include improved public transport, smart mobility, carsharing and electric hybrids. Fossil-fuel powered passenger cars can be converted to electric propulsion. The production of alternative fuel without GHG emissions is only possible with high conversion losses. Furthermore, moving away from a car-dominated transport system towards low-carbon advanced public transport system is important.

Heavyweight, large personal vehicles (such as cars) require a lot of energy to move and take up much urban space. Several alternatives modes of transport are available to replace these. The European Union has made smart mobility part of its European Green Deal and in smart cities, smart mobility is also important.

Electric vehicles

See also: Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles and Alternative fuel vehicle

Between a quarter and three-quarters of cars on the road by 2050 are forecast to be electric vehicles. EVs use 38 megajoules per 100 km in comparison to 142 megajoules per 100 km for ICE cars. Hydrogen can be a solution for long-distance transport by trucks and hydrogen-powered ships where batteries alone are too heavy.

GHG emissions depend on the amount of green energy being used for battery or fuel cell production and charging. In a system mainly based on electricity from fossil fuels, emissions of electric vehicles can even exceed those of diesel combustion.

Shipping

Further information: Environmental effects of shipping § Greenhouse gas pollutantsIn the shipping industry, the use of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as a marine bunker fuel is driven by emissions regulations. Ship operators have to switch from heavy fuel oil to more expensive oil-based fuels, implement costly flue gas treatment technologies or switch to LNG engines. Methane slip, when gas leaks unburned through the engine, lowers the advantages of LNG. Maersk, the largest container shipping line and vessel operator in the world, warns of stranded assets when investing into transitional fuels like LNG. The company lists green ammonia as one of the preferred fuel types of the future and has announced the first carbon-neutral vessel on the water by 2023, running on carbon-neutral methanol.

Hybrid and all electric ferries are suitable for short distances. Norway's goal is an all electric fleet by 2025. The E-ferry Ellen, which was developed in an EU-backed project, is in operation in Denmark.

Air travel

Further information: environmental impact of aviationIn aviation, current 180 Mt of CO2 emissions (11% of emissions in transport) are expected to rise in most projections, at least until 2040. Aviation biofuel and hydrogen can only cover a small proportion of flights in the coming years. The market entry for hybrid-driven aircraft on regional scheduled flights is projected after 2030, for battery-powered aircraft after 2035. In October 2016, the 191 nations of the ICAO established the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), requiring operators to purchase carbon offsets to cover their emissions above 2020 levels, starting from 2021. This is voluntary until 2027.

This section is an excerpt from Environmental impact of aviation.

Aircraft engines produce gases, noise, and particulates from fossil fuel combustion, raising environmental concerns over their global effects and their effects on local air quality. Jet airliners contribute to climate change by emitting carbon dioxide (CO2), the best understood greenhouse gas, and, with less scientific understanding, nitrogen oxides, contrails and particulates. Their radiative forcing is estimated at 1.3–1.4 that of CO2 alone, excluding induced cirrus cloud with a very low level of scientific understanding. In 2018, global commercial operations generated 2.4% of all CO2 emissions.

Jet airliners have become 70% more fuel efficient between 1967 and 2007, and CO2 emissions per revenue ton-kilometer (RTK) in 2018 were 47% of those in 1990. In 2018, CO2 emissions averaged 88 grams of CO2 per revenue passenger per km.

While the aviation industry is more fuel efficient, overall emissions have risen as the volume of air travel has increased. By 2020, aviation emissions were 70% higher than in 2005 and they could grow by 300% by 2050.Agriculture

See also: Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, Environmental impact of meat production, Insects as food, and Sustainable agricultureAs 25% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) are coming from agriculture and land use, it is impossible to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees without addressing the emissions from agriculture. During 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, 45 countries pledged to give more than 4 billion dollars for transition to sustainable agriculture. The organization "Slow Food" expressed concern about the effectivity of the spendings, as they concentrate on technological solutions and reforestation en place of "a holistic agroecology that transforms food from a mass-produced commodity into part of a sustainable system that works within natural boundaries."

With 21% of the global methane emissions, cattle are a major driver on global warming. When rainforests are cut and the land is converted for grazing, the impact is even higher. This results in up to 335 kg CO2eq emissions for the production of 1 kg beef in Brazil when using a 30-year time horizon. Other livestock, manure management and rice cultivation also produce relevant GHG emissions, in addition to fossil fuel combustion in agriculture.

Investment in improving and scaling up the production of dairy and meat alternatives leads to big greenhouse gas reductions compared with other investments. Also, photovoltaic-driven microbial protein production could use 10 times less land for an equivalent amount of protein compared to soybean cultivation.

Agricultural changes may require complementary laws and policies to drive and support dietary shifts, including changes in pet food, increases in organic food products, and substantial reductions of meat-intake (food miles usually do not play a large role).

Regenerative agriculture includes conservation tillage, diversity, rotation and cover crops, minimizing physical disturbance, minimizing the usage of chemicals. It has other benefits like improving the state of the soil and consequently yields. A research made by the Rodale institute suggests that a worldwide transition to regenerative agriculture can soak around 100% of the greenhouse gas emissions currently emitted by people. Restoring grasslands stores CO2 with estimates that increasing the carbon content of the soils in the world's 3.5 billion hectares of agricultural grassland by 1% would offset nearly 12 years of CO2 emissions. Allan Savory, as part of holistic management, claims that while large herds are often blamed for desertification, prehistoric lands supported large or larger herds and areas where herds were removed in the United States are still desertifying. Grazers, such as livestock that are not left to wander, would eat the grass and would minimize any grass growth. However, carbon sequestration is maximized when only part of the leaf matter is consumed by a moving herd as a corresponding amount of root matter is sloughed off too sequestering part of its carbon into the soil.

In the United States, soils account for about half of agricultural GHGs while agriculture, forestry and other land use emits 24%.

The US EPA says soil management practices that can reduce the emissions of nitrous oxide (N

2O) from soils include fertilizer usage, irrigation, and tillage.

Important mitigation options for reducing the greenhouse gas emissions from livestock include genetic selection, introduction of methanotrophic bacteria into the rumen, vaccines, feeds, toilet-training, diet modification and grazing management. Other options include just using ruminant-free alternatives instead, such as milk substitutes and meat analogues. Non-ruminant livestock (e.g. poultry) generates far fewer emissions.

Methods that enhance carbon sequestration in soil include no-till farming, residue mulching and crop rotation, all of which are more widely used in organic farming than in conventional farming. Because only 5% of US farmland currently uses no-till and residue mulching, there is a large potential for carbon sequestration.

Farming can deplete soil carbon and render soil incapable of supporting life. However, conservation farming can protect carbon in soils, and repair damage over time. The farming practice of cover crops has been recognized as climate-smart agriculture. Best management practices for European soils were described to increase soil organic carbon: conversion of arable land to grassland, straw incorporation, reduced tillage, straw incorporation combined with reduced tillage, ley cropping system and cover crops.

Agroforestry is one way to achieve sustainable intensification, which is farming method that can both boosts yield to supply the growing population and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Agroforestry is the practice of integrating trees and shrubs into crop and animal farming systems, creating environmental benefits. Trees can absorb carbon dioxide from the air, leaves from the trees can enrich the soil, manure from livestock can nutrient crops and trees. Nitrogen can also be fixed by trees, which benefits crops. This method intensifies agriculture productivity while prevents deforestation, which all largely contribute to rising of CO2.

Methane emissions in rice cultivation can be cut by implementing an improved water management, combining dry seeding and one drawdown, or a perfect execution of a sequence of wetting and drying. This results in emission reductions of up to 90% compared to full flooding and even increased yields.

Demand management and social aspects

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report pointed out in 2022: "To enhance well-being, people demand services and not primary energy and physical resources per se. Focusing on demand for services and the different social and political roles people play broadens the participation in climate action." The report explains that behavior, lifestyle, and cultural change have a high mitigation potential in some sectors, particularly when complementing technological and structural change.

Mitigation options that reduce demand for products or services are helping people make personal choices to reduce their carbon footprint, for example in their choice of transport options or their diets. This means there are many social aspects with the demand-side mitigation actions. For example, people with high socio-economic status often contribute more to greenhouse gas emissions than those from a lower socio-economic status. By reducing their emissions and promoting green policies, these people could become "role models of low-carbon lifestyles". However, there are many psychological variables that influence motivation of people to reduce their demand such as awareness and perceived risk. Government policies can support or hinder demand-site mitigation options. For example, public policy can promote circular economy concepts which would support climate change mitigation. Reducing GHG emissions is linked to sharing economy and circular economy.

It has been estimated that only 0.12% of all funding for climate-related research is spent on the social science of climate change mitigation. Vastly more funding is spent on natural science studies of climate change and considerable sums are also spent on studies of impact of and adaptation to climate change.

Lifestyle and behavior

Individual action on climate change describes the personal choices that everyone can make to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of their lifestyles and catalyze climate action. These actions can focus directly on how choices create emissions, such as reducing consumption of meat or flying, or can be more focus on inviting political action on climate or creating greater awareness how society can become more green.

Excessive consumption is one of the most significant contributors to climate change and other environmental issue than population increase. High consumption lifestyles have a greater environmental impact, with the richest 10% of people emitting about half the total lifestyle emissions. Creating changes in personal lifestyle, can change social and market conditions leading to less environmental impact. People who wish to reduce their carbon footprint (particularly those in high income countries with high consumption lifestyles), can for example reduce their air travel for holidays, use bicycles instead of cars on a daily basis, eat a plant-based diet, and use consumer products for longer. Avoiding meat and dairy products has been called "the single biggest way" individuals can reduce their environmental impacts.Personal carbon trading

Some forms of personal carbon trading (carbon rationing) could be an effective component of climate change mitigation, with the economic recovery of COVID-19 and new technical capacity having opened a favorable window of opportunity for initial test runs of such in appropriate regions, while many questions remain largely unaddressed. However, carbon rationing could have a larger effect on poorer households as "people in the low-income groups may have an above-average energy use, because they live in inefficient homes".

Dietary change

Main article: Low-carbon dietThe widespread adoption of a vegetarian diet could cut food-related greenhouse gas emissions by 63% by 2050. Addressing the high methane emissions by cattle, a 2016 study analyzed surcharges of 40% on beef and 20% on milk and suggests that an optimum plan would reduce emissions by 1 billion tonnes per year. China introduced new dietary guidelines in 2016 which aim to cut meat consumption by 50% and thereby reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 1 billion tonnes by 2030. Overall, food accounts for the largest share of consumption-based GHG emissions with nearly 20% of the global carbon footprint. Almost 15% of all anthropogenic GHG emissions has been attributed to the livestock sector alone.

A shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate climate change. In particular, reducing meat consumption would help to reduce methane emissions. If high-income nations switched to a plant-based diet, vast amounts of land used for animal agriculture could be allowed to return to their natural state, which in turn has the potential to sequester 100 billion tons of CO2 by the end of the century.

Urban systems

Main article: Urban planning Further information: Smart mobility, Smart growth, and Carfree city

Effective urban planning to reduce sprawl aims to decrease the distance travelled by vehicles, lowering emissions from transportation. Personal cars are extremely inefficient at moving passengers, while public transport and bicycles are many times more efficient in an urban context. Switching from cars by improving walkability and cycling infrastructure is either free or beneficial to a country's economy as a whole.

Cities have big potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. They emitted 28 GtCO2-eq in 2020, about half of total emissions. City planning, supporting mixed use of space, transit, walking, cycling, sharing vehicles can reduce urban emissions by 23% – 26%. Urban forests, lakes and other blue and green infrastructure can reduce emissions directly and indirectly by reduced energy demand for cooling.

Reducing the number of cars on the road, for example through proof-of-parking requirements, corporate car sharing, road reallocation (from only car use to cycling road, ...), circulation plans, bans on on-street parking or by increasing the costs of car ownership can help in reducing traffic congestion in cities.

Population growth

Further information: Individual action on climate change § Family sizePopulation growth results in higher greenhouse gas emissions in most regions, particularly Africa. However, economic growth has a bigger effect than population growth. It is the rising incomes, changes in consumption and dietary patterns, together with population growth, which causes pressure on land and other natural resources, and leads to more greenhouse gas emissions and less carbon sinks. Scholars have pointed out that "In concert with policies that end fossil fuel use and incentivize sustainable consumption, humane policies that slow population growth should be part of a multifaceted climate response." It is known that "advances in female education and reproductive health, especially voluntary family planning, can contribute greatly to reducing world population growth".

Investment and finance

Investment

Main article: Business action on climate change

More than 1000 organizations with a worth of US$8 trillion have made commitments to fossil fuel divestment. Socially responsible investing funds allow investors to invest in funds that meet high environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) standards. Proxy firms can be used to draft guidelines for investment managers that take these concerns into account.

As well as a policy risk, Ernst and Young identify physical, secondary, liability, transitional and reputation-based risks. Therefore, it is increasingly seen to be in the interest of investors to accept climate change as a real threat which they must proactively and independently address.

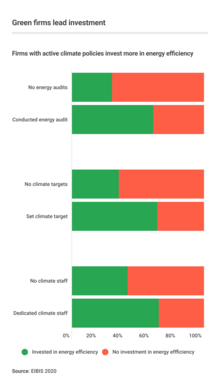

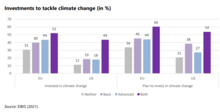

The European Investment Bank's investment survey 2021 found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change was addressed by 43% of EU enterprises. Despite the pandemic's effect on businesses, the percentage of firms planning climate-related investment rose to 47%. This was a rise from 2020, when the percentage of climate related investment was at 41%.

In 2021, firms' investments in climate change mitigation were being hampered by uncertainty about the regulatory environment and taxation.

As of 2021, one current approach under development is binary "labelling" of investments as "green" according to an EU governmental body-created "taxonomy" for voluntarily financial investment redirection based on this categorization.

Funding

Main article: Climate financeFunding, such as the Green Climate Fund, is often provided by nations, groups of nations and increasingly NGO and private sources. These funds are often channelled through the Global Environmental Facility (GEF). This is an environmental funding mechanism in the World Bank which is designed to deal with global environmental issues. The GEF was originally designed to tackle four main areas: biological diversity, climate change, international waters and ozone layer depletion, to which land degradation and persistent organic pollutant were added. The GEF funds projects that are agreed to achieve global environmental benefits that are endorsed by governments and screened by one of the GEF's implementing agencies.

Economics

Main article: Economics of climate change mitigation See also: Green industrial policyThere is a debate about a potentially critical need for new ways of economic accounting, including directly monitoring and quantifying positive real-world environmental effects such as air quality improvements and related unprofitable work like forest protection, alongside far-reaching structural changes of lifestyles as well as acknowledging and moving beyond the limits of current economics such as GDP. Some argue that for effective climate change mitigation degrowth has to occur, while some argue that eco-economic decoupling could limit climate change enough while continuing high rates of traditional GDP growth. There is also research and debate about requirements of how economic systems could be transformed for sustainability – such as how their jobs could transition harmonously into green jobs – a just transition – and how relevant sectors of the economy – like the renewable energy industry and the bioeconomy – could be adequately supported.

While degrowth is often believed to be associated with decreased living standards and austerity measures, many of

its proponents seek to expand universal public goods (such as public transport), increase health (fitness, wellbeing and freedom from diseases) and increase various forms of, often unconventional commons-oriented, labor.

To this end, the application of both advanced technologies and reductions in various demands, including via overall reduced labor time or sufficiency-oriented strategies, are considered to be important by some.

On the level of international trade, domestic trade, production and product designs, policies such as for "digital product passports" have been proposed to link products with environment-related information which could be a requirement for both further measures as well as unfacilitated bottom-up consumer- and business-adaptations.

Companies, investors and politicians

Sometimes, top contributors to greenhouse gas emissions are identified as the companies emitting most GHGs. Similarly, investing asset management firms are often identified as controllers of large amounts of contemporary financial value with insufficient dedication to climate change targets, with the largest four asset managers controlling around 20% of the world's listed market values – an aggregate assets under management of $20 trillion as of 2021.

However, it may not necessarily be the structural interest of these companies to help mitigate climate change sufficiently instead of striving to generate near-maximum profit in the contemporary socioeconomic system, a globalized competitive consumption-demanding environment, and use all legal means to delay climate change action if such is beneficial (see below) – their products are being bought by consumers (for various reasons), the stock market likely underestimates (or cannot value) e.g. social benefits of climate mitigation, they are regulatable by governments, and don't have as much power as many large states (or groups of such) which e.g. have capacities of law enforcement and military, customs, legal frameworks and for business-, media-, education-, global-, trade- and industrial policies. A fraction of such policies or measures are invariably initially at least partly unpopular, and in the contemporary decision-making environment of (campaign-marketing-, party-, media-, and electoral/referendum plain votes-based) politics, unpopular decisions may be difficult for politicians to enact directly or help facilitate indirectly. The question of the largest responsibility or driver may be about who is holding (or withholding) the power (and capacity) to create and change the systems that cause climate change, such as the transportation system. While it has been pointed out that blaming drivers may not be constructive in terms of climate change mitigation, understanding these links of the supply chain may allow better understanding of the complex system or untangling the structures of power and decision-making that inhibit climate action.

Costs

Globally, the benefits of keeping warming under 2 °C exceed the costs. However, some consider cost–benefit analysis unsuitable for analysing climate change mitigation as a whole but still useful for analysing the difference between a 1.5 °C target and 2 °C. The OECD has been applying economic models and qualitative assessments to inform on climate change benefits and tradeoffs. One way of estimating the cost of reducing emissions is by considering the likely costs of potential technological and output changes. Policy makers can compare the marginal abatement costs of different methods to assess the cost and amount of possible abatement over time. The marginal abatement costs of the various measures will differ by country, by sector, and over time. Mitigation costs will vary according to how and when emissions are cut: early, well-planned action will minimise the costs.

Many economists estimate the cost of climate change mitigation at between 1% and 2% of GDP. In 2019, scientists from Australia and Germany presented the "One Earth Climate Model" showing how temperature increase can be limited to 1.5 °C for 1.7 trillion dollars a year. According to this study, a global investment of approximately $1.7 trillion per year would be needed to keep global warming below 1.5°C. The method used by the One Earth Climate Model does not resort to dangerous geo-engineering methods. Whereas this is a large sum, it is still far less than the subsidies governments currently provided to the ailing fossil fuel industry, estimated at more than $5 trillion per year by the International Monetary Fund. Abolishing fossil fuel subsidies is very important but must be done carefully to avoid making poor people poorer. Ian Parry, lead author of the 2021 IMF report "Still Not Getting Energy Prices Right: A Global and Country Update of Fossil Fuel Subsidies", said: "Some countries are reluctant to raise energy prices because they think it will harm the poor. But holding down fossil fuel prices is a highly inefficient way to help the poor, because most of the benefits accrue to wealthier households. It would be better to target resources towards helping poor and vulnerable people directly."

Benefits

By limiting climate change, some of the costs of the effects of climate change can be avoided.

According to the Stern Review, inaction can be as high as the equivalent of losing at least 5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) each year, now and forever (up to 20% of the GDP or more when including a wider range of risks and impacts), whereas mitigating climate change will only cost about 2% of the GDP. Also, delaying to take significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions may not be a good idea, when seen from a financial perspective. Mitigation solutions are often evaluated in terms of costs and greenhouse gas reduction potentials, missing out on the consideration of direct effects on human well-being.

Mitigation measures may have many health co-benefits – potential measures can not only mitigate future health impacts from climate change but also improve health directly.

Climate change mitigation is also an issue of intergenerational justice with nonintervention thought by some to violate future people's freedom – conversely, mitigation may preserve societal freedoms and range of viable basic choices.

The research organization Project Drawdown identified global climate solutions and ranked them according to their benefits. Early deaths due to fossil fuel air pollution with a temperature rise to 2 °C cost more globally than mitigation would: and in India cost 4 to 5 times more. Air quality improvement is a near-term benefit among the many societal benefits from climate change mitigation, including substantial health benefits. Studies suggest that demand-side climate change mitigation solutions have largely beneficial effects on 18 constituents of well-being.

Sharing

One of the aspects of mitigation is how to share the costs and benefits of mitigation policies. Rich people tend to emit more GHG than poor people. Activities of the poor that involve emissions of GHGs are often associated with basic needs, such as cooking. For richer people, emissions tend to be associated with things such as eating beef, cars, frequent flying, and home heating. The impacts of cutting emissions could therefore have different impacts on human welfare according to wealth.

Distributing emissions abatement costs

There have been different proposals on how to allocate responsibility for cutting emissions (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 103–105):

- Egalitarianism: this system interprets the problem as one where each person has equal rights to a global resource, i.e., polluting the atmosphere.

- Basic needs: this system would have emissions allocated according to basic needs, as defined according to a minimum level of consumption. Consumption above basic needs would require countries to buy more emission rights. From this viewpoint, developing countries would need to be at least as well off under an emissions control regime as they would be outside the regime.

- Proportionality and polluter-pays principle: Proportionality reflects the ancient Aristotelian principle that people should receive in proportion to what they put in, and pay in proportion to the damages they cause. This has a potential relationship with the "polluter-pays principle", which can be interpreted in a number of ways:

- Historical responsibilities: this asserts that allocation of emission rights should be based on patterns of past emissions. Two-thirds of the stock of GHGs in the atmosphere at present is due to the past actions of developed countries (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 29).

- Comparable burdens and ability to pay: with this approach, countries would reduce emissions based on comparable burdens and their ability to take on the costs of reduction. Ways to assess burdens include monetary costs per head of population, as well as other, more complex measures, like the UNDP's Human Development Index.

- Willingness to pay: with this approach, countries take on emission reductions based on their ability to pay along with how much they benefit from reducing their emissions.

Specific proposals

- Equal per capita entitlements: this is the most widely cited method of distributing abatement costs, and is derived from egalitarianism (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 106–107). This approach can be divided into two categories. In the first category, emissions are allocated according to national population. In the second category, emissions are allocated in a way that attempts to account for historical (cumulative) emissions.

- Status quo: with this approach, historical emissions are ignored, and current emission levels are taken as a status quo right to emit (Banuri et al., 1996, p. 107). An analogy for this approach can be made with fisheries, which is a common, limited resource. The analogy would be with the atmosphere, which can be viewed as an exhaustible natural resource (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 27). In international law, one state recognized the long-established use of another state's use of the fisheries resource. It was also recognized by the state that part of the other state's economy was dependent on that resource.

Barriers

See also: Climate justice § Debates and issues

It has been suggested that the main barriers to implementation are uncertainty, institutional void, short time horizon of policies and politicians and missing motives and willingness to start adapting as well as the negative impacts of COVID-19 pandemic When information on climate change is held between the large numbers of actors involved it can be highly dispersed, context specific or difficult to access causing fragmentation to be a barrier. The short time horizon of policies and politicians often means that climate change policies are not implemented in favour of socially favoured societal issues. Statements are often posed to keep the illusion of political action to prevent or postpone decisions being made. There may be cause for concern about metal requirement for relevant technologies such as photovoltaics. Many developing nations have made national adaptation programs which are frameworks to prioritize adaption needs.

Carbon budgets by country

An international policy to allocate carbon budgets to individual countries has not been implemented. This question raises fairness issues. With a linear reduction starting from the status quo, industrial countries would have a greater share of the remaining global budget. Using an equal share per capita globally, emission cuts in industrial countries would have to be extremely sharp.

Geopoliticial impacts

Further information: Renewable energy § Geopolitics of renewable energyIn 2019, oil and gas companies were listed by Forbes with sales of US$4.8 trillion, about 5% of the global GDP. Net importers such as China and the EU would gain advantages from a transition to low-carbon technologies driven by technological development, energy efficiency or climate change policy, while Russia, the USA or Canada could see their fossil fuel industries nearly shut down. On the other hand, countries with large areas such as Australia, Russia, China, the US, Canada and Brazil and also Africa and the Middle East have a potential for huge installations of renewable energy. The production of renewable energy technologies requires rare-earth elements with new supply chains.

Economic interests of fossil fuel companies