| Revision as of 01:14, 8 November 2022 editBri (talk | contribs)Edit filter helpers, Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers172,762 edits →See also: rmv repeated terms, WP:NOTSEEALSO← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:11, 7 December 2022 edit undoZsiadek (talk | contribs)24 edits Added in information regarding the formation of the farrier profession and a more detailed etymology.Tag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| ==History and ceremonial== | ==History and ceremonial== | ||

| While the practice of putting protective hoof coverings on horses dates back to the first century,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2012-03-06 |title=Horse Shoes History |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120306031347/http://www.equisearch.com/horses_care/health/hoof_care/eqhorsesho610/ |access-date=2022-10-16 |website=web.archive.org}}</ref> evidence suggests that the practice of nailing iron shoes into a horse’s hoof is a much later invention. One of the first archaeological discoveries of an iron horseshoe was found in the tomb of Merovingian king ], who reigned from 458-481/82. The discovery was made by Adrien Quinquin in 1653, and the findings were written about by ] in 1655. Chifflet wrote that the iron horseshoe was so rusted that it fell apart as he attempted to clean it. He did, however, make an illustration of the shoe and noted that it had four holes on each side for nails.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chifflet |first=Jean-Jacques |title=anastasis childerici i francorum regis, sive thesaurus sepulchralis tornaci neviorum effossus et commentario illustratus |publisher=Plantin Press |year=1655 |location=Antwerp |pages=249}}</ref> Although this discovery places the existence of iron horseshoes during the later half of the 5th century, their further usage is not recorded until closer to the end of the millennia. Carolingian ], legal acts composed and published by Frankish kings until the 9th Century, display a high degree of attention to detail when it came to military matters, even going as far as to specify which weapons and equipment soldiers were to bring when called upon for war.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=France |first=John |title=Warfare in the Dark Ages |last2=DeVries |publisher=Ashgate |year=2008 |location=Hampshire, England |pages=321-340}}</ref> With each Capitulary that calls for horsemen, no mention of horseshoes can be found. Excavations from ] burials also demonstrate a lack of iron horseshoes, even though many of the stirrups and other horse tack survived. A burial dig in Slovenia discovered iron bits, stirrups, and saddle parts but no horseshoes.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1287098588 |title=Horse and Rider in the late Viking Age Equestrian burial in perspective. |date=2021 |others=Project Muse, Project MUSE, Anne Pedersen, Merethe Schifter Bagge |isbn=978-87-7184-998-1 |edition=1 |location=Baltimore, Md. |oclc=1287098588}}</ref> The first literary mention of nailed horseshoes is found within Ekkehard’s ],<ref name=":0" /> written c. 920 AD. The practice of shoeing horses in Europe likely originated in Western Europe, where they had more need due to the way the climate affected horses' hooves, before spreading eastward and northward by 1000 AD. | |||

| Historically, the jobs of farrier and ] were practically synonymous, shown by the etymology of the word: ''farrier'' comes from ]: ''ferrier'' (blacksmith), from the ] word ''ferrum'' (]).<ref> at Etymonline.com</ref> In 1350, a statute from ] designated the shoer of horses at court to be the ''ferrour des chivaux'', who would be sworn in before judges. The ''ferrour des chivaux'' would swear to do his craft properly and to limit himself solely to it.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fleming |first=George |title=Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States, Volume 13 |publisher=The Military Service Institution of the United States |date=January 1892 |pages=986–987}}</ref> A farrier's work in ] or pre-] Europe would have included ], as well as the fabrication and repair of tools, the forging of architectural pieces, and so on. Modern-day farriers usually specialize in horseshoeing, focusing their time and effort on the care of the horse's hoof. Hence, modern farriers and blacksmiths are considered to be in separate, albeit related, trades. | |||

| The task of shoeing horses was originally performed by blacksmiths, owing to the origin of the word found within the Latin ''ferrum''. However, by the time of ] (r. 1327-1377) the position, among others, had become much more specialized. This was part of a larger trend in specialization and the division of labour in England at the time.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Britnell |first=R. H. |date=2001 |title=Specialization of Work in England, 1100-1300 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3091711 |journal=The Economic History Review |volume=54 |issue=1 |pages=1–16 |issn=0013-0117}}</ref> In 1350, Edward released an ordinance concerning pay and wages within the city of London. In the ordinance it mentioned farriers and decreed that they were not to charge more for their services than "they were wont to take before the time of the pestilence."<ref>{{Citation |last=Holland |first=John |title=LONDON LIFE AND WORKS |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139857093.007 |work=Memorials of Sir Francis Chantrey |pages=241–306 |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |access-date=2022-11-03}}</ref> The pestilence mentioned was the ], which places the existence of farriers as a trade independent of blacksmiths at the latest in 1346. In 1350, a statute from Edward designated the shoer of horses at court to be the ferrour des chivaux (literally Shoer of Horses), who would be sworn in before judges. The ferrour des chivaux would swear to do his craft properly and to limit himself solely to it.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fleming |first=George |date=January 1892 |title=Shoeing of Army Horses |url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=O_I5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA986&lpg=PA986&dq=edward+ii,+1359,+forges,+equipment&source=bl&ots=BZUpD5Rphu&sig=wC5x5L4vYqKmUIo6MY0uHZBijRg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=zELuVLjGB4awyQTM6IDoAw&ved=0CD4Q6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=edward%20ii%2C%201359%2C%20forges%2C%20equipment&f=false |journal=Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States |volume=13 |pages=986-987}}</ref> The increasing division of labour in England, especially in regards to the farriers, proved beneficial for Edward III during the first phase of the ]. The English army traveled into France with an immense baggage train that possessed its own forges in order for the Sergeants-Farrier and his assistants to shoe horses in the field. The increased specialization of the 14th Century allowed Edward to create a self-sufficient army, thus contributing to his military success in France. | |||

| In the British Army, the ] have ] who march in parade in ceremonial dress, carrying their historical axes with spikes. They are a familiar sight at the annual ] ceremony in the ]. There is also a farrier on call "round the clock, twenty-four hours a day, at ]".<ref name="HC Farriers">. Accessed 20 March 2012.</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| In the United Kingdom, the ] is one of the ] of the City of London. The Farriers, or horseshoe makers, organised in 1356. It received a ] of incorporation in 1571. Over the years, the Company has evolved from a trade association for horseshoe makers into an organisation for those devoted to equine welfare, including veterinary surgeons. | |||

| The word farrier can be traced back to the ] word ferrǒur, which referred to a blacksmith who also shoed horses. Ferrǒur can be traced back to the even earlier ] ferreor, which in itself is based upon the Latin ferrum, meaning iron.<ref>{{Cite web |date=Accessed 16 October 2022 |title=Ferrour |url=https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/MED15747. |access-date=16 October, 2022 |website=The Middle English Compendium}}</ref> | |||

| ==Work== | ==Work== | ||

Revision as of 19:11, 7 December 2022

Specialist in equine hoof care For other uses, see Farrier (disambiguation).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Farrier" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

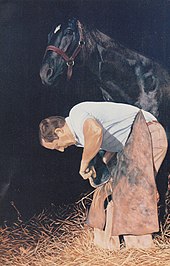

A farrier is a specialist in equine hoof care, including the trimming and balancing of horses' hooves and the placing of shoes on their hooves, if necessary. A farrier combines some blacksmith's skills (fabricating, adapting, and adjusting metal shoes) with some veterinarian's skills (knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the lower limb) to care for horses' feet.

History and ceremonial

While the practice of putting protective hoof coverings on horses dates back to the first century, evidence suggests that the practice of nailing iron shoes into a horse’s hoof is a much later invention. One of the first archaeological discoveries of an iron horseshoe was found in the tomb of Merovingian king Childeric I, who reigned from 458-481/82. The discovery was made by Adrien Quinquin in 1653, and the findings were written about by Jean-Jacques Chifflet in 1655. Chifflet wrote that the iron horseshoe was so rusted that it fell apart as he attempted to clean it. He did, however, make an illustration of the shoe and noted that it had four holes on each side for nails. Although this discovery places the existence of iron horseshoes during the later half of the 5th century, their further usage is not recorded until closer to the end of the millennia. Carolingian Capitularies, legal acts composed and published by Frankish kings until the 9th Century, display a high degree of attention to detail when it came to military matters, even going as far as to specify which weapons and equipment soldiers were to bring when called upon for war. With each Capitulary that calls for horsemen, no mention of horseshoes can be found. Excavations from Viking-age burials also demonstrate a lack of iron horseshoes, even though many of the stirrups and other horse tack survived. A burial dig in Slovenia discovered iron bits, stirrups, and saddle parts but no horseshoes. The first literary mention of nailed horseshoes is found within Ekkehard’s Waltharius, written c. 920 AD. The practice of shoeing horses in Europe likely originated in Western Europe, where they had more need due to the way the climate affected horses' hooves, before spreading eastward and northward by 1000 AD.

The task of shoeing horses was originally performed by blacksmiths, owing to the origin of the word found within the Latin ferrum. However, by the time of Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377) the position, among others, had become much more specialized. This was part of a larger trend in specialization and the division of labour in England at the time. In 1350, Edward released an ordinance concerning pay and wages within the city of London. In the ordinance it mentioned farriers and decreed that they were not to charge more for their services than "they were wont to take before the time of the pestilence." The pestilence mentioned was the Black Death, which places the existence of farriers as a trade independent of blacksmiths at the latest in 1346. In 1350, a statute from Edward designated the shoer of horses at court to be the ferrour des chivaux (literally Shoer of Horses), who would be sworn in before judges. The ferrour des chivaux would swear to do his craft properly and to limit himself solely to it. The increasing division of labour in England, especially in regards to the farriers, proved beneficial for Edward III during the first phase of the Hundred Years' War. The English army traveled into France with an immense baggage train that possessed its own forges in order for the Sergeants-Farrier and his assistants to shoe horses in the field. The increased specialization of the 14th Century allowed Edward to create a self-sufficient army, thus contributing to his military success in France.

Etymology

The word farrier can be traced back to the Middle English word ferrǒur, which referred to a blacksmith who also shoed horses. Ferrǒur can be traced back to the even earlier Old French ferreor, which in itself is based upon the Latin ferrum, meaning iron.

Work

A farrier's routine work is primarily hoof trimming and shoeing. In ordinary cases, trimming each hoof so it retains proper foot function is important. If the animal has a heavy work load, works on abrasive footing, needs additional traction, or has pathological changes in the hoof or conformational challenges, then shoes may be required. Additional tasks for the farrier include dealing with injured or diseased hooves and application of special shoes for racing, training, or "cosmetic" purposes. Horses with certain diseases or injuries may need remedial procedures for their hooves, or need special shoes.

Tools used

| Tool | Picture | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Anvil, hammer |

|

Used to shape horseshoes to fit horse's feet |

| Forge and tongs |

|

Used to heat horseshoes to allow custom shaping and specialized design, tongs hold a hot shoe in both the furnace and on the anvil |

| Clinchers | Used to bend over ("clinch") ends of nails to hold the shoe in place | |

| Hammer | Two types, a larger design used on the anvil to shape shoes, a smaller one used to drive nails into hoof wall, through nail holes in shoe | |

| Hoof knife |

|

Used to trim frog and sole of hoof |

| Hoof nippers |

|

Used to trim hoof wall |

| Hoof testers | Used to detect cracks, weakness or abscess in the hoof | |

| Rasp |

|

Used to finish trim and smooth out edges of hoof |

| Stand |

|

Used to rest a horse's hoof off the ground when rasping the toe area. |

Qualifications

In countries such as the United Kingdom, people other than registered farriers cannot legally call themselves a farrier or carry out any farriery work (in the UK, this is under the Farriers (Registration) Act 1975). The primary aim of the act is to "prevent and avoid suffering by and cruelty to horses arising from the shoeing of horses by unskilled persons".

However, in other countries, such as the United States, farriery is not regulated, no legal certification exists, and qualifications can vary. In the US, four organizations - the American Farrier's Association (AFA), the Guild of Professional Farriers (GPF), the Brotherhood of Working Farriers, and the Equine Lameness Prevention Organization (ELPO) - maintain voluntary certification programs for farriers. Of these, the AFA's program is the largest, with about 2800 certified farriers. Additionally, the AFA program has a reciprocity agreement with the Farrier Registration Council and the Worshipful Company of Farriers in the UK.

Within the certification programs offered by the AFA, the GPF, and the ELPO, all farrier examinations are conducted by peer panels. The farrier examinations for these organizations are designed so that qualified farriers may obtain a formal credential indicating they meet a meaningful standard of professional competence as determined by technical knowledge and practical skills examinations, length of field experience, and other factors. Farriers who have received a certificate of completion for attending a farrier school or course may represent themselves as having completed a particular course of study. Sometimes, usually for purposes of brevity, they use the term "certified" in advertising.

Where professional registration exists, on either a compulsory or voluntary basis, a requirement for continuing professional development activity often exists to maintain a particular license or certification. For instance, farriers voluntarily registered with the American Association of Professional Farriers require at least 16 hours of continuing education every year to maintain their accreditation.

See also

- Equine anatomy

- Equine forelimb anatomy

- Equine podiatry

- Household Cavalry Army Farriers

- Natural hoof care

References

- "Horse Shoes History". web.archive.org. 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- Chifflet, Jean-Jacques (1655). anastasis childerici i francorum regis, sive thesaurus sepulchralis tornaci neviorum effossus et commentario illustratus. Antwerp: Plantin Press. p. 249.

- ^ France, John; DeVries (2008). Warfare in the Dark Ages. Hampshire, England: Ashgate. pp. 321–340.

- Horse and Rider in the late Viking Age Equestrian burial in perspective. Project Muse, Project MUSE, Anne Pedersen, Merethe Schifter Bagge (1 ed.). Baltimore, Md. 2021. ISBN 978-87-7184-998-1. OCLC 1287098588.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Britnell, R. H. (2001). "Specialization of Work in England, 1100-1300". The Economic History Review. 54 (1): 1–16. ISSN 0013-0117.

- Holland, John, "LONDON LIFE AND WORKS", Memorials of Sir Francis Chantrey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 241–306, retrieved 2022-11-03

- Fleming, George (January 1892). "Shoeing of Army Horses". Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. 13: 986–987.

- "Ferrour". The Middle English Compendium. Accessed 16 October 2022. Retrieved 16 October, 2022.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=and|date=(help) - Audrey Pavia; Kate Gentry-Running (4 February 2011). Horse Health and Nutrition For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-05232-7.

- "The Value Of Proper Hoof Care". San Tan Times. 2019-02-05. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- J. Warren Evans (13 December 2000). Horses, 3rd Edition: A Guide to Selection, Care, and Enjoyment. Henry Holt and Company. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-8050-7251-8.

- Dave Millwater (19 October 2009). The New Dictionary of Farrier Terms 2. 7. 2-PB. Lulu.com. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-557-15559-0.

- Cherry Hill; Richard Klimesh (2009). Horse Hoof Care. Storey Pub. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-60342-088-4.

- Andrea E. Floyd; R. A. Mansmann (2007). Equine Podiatry. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-7216-0383-4.

- Tearney, Pat (1 May 2011). "Getting More Out of Your Hoof Nippers". American Farriers Journal.

- Gregory, Chris (1 January 2011). "A Valuable Diagnostic Tool When Properly Used". American Farriers Journal.

- "Why Rasps are the Most Important -- Yet Most Neglected -- Tool in your Shoeing Box".

- Farriers (Registration) Act 1975

- "Finding a Farrier". October 2000.

- "The American Farriers Association". Americanfarriers.org. 2011-04-28. Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- Registration guidelines for The Guild of Professional Farriers

- "Farrier Accreditation". Archived from the original on 2016-10-28.