| Revision as of 18:08, 7 March 2007 view source212.32.93.58 (talk) →Beliefs← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:09, 7 March 2007 view source 212.32.93.58 (talk) →Christian lifeNext edit → | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| ==Worship and practices== | ==Worship and practices== | ||

| ===Christian life=== | ===Christian life=== | ||

| IS A HALF LIFE | |||

| ] believe that ] is the mediator of the ] (see ). His famous ] representing ] is considered by many Christian scholars to be the ] <ref>See also ].</ref> of the proclamation of the ] by ] from ]]] | |||

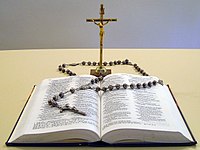

| Christians believe that all people should strive to follow Christ in their everyday actions. For many, this includes obedience to the ], for details see ]. Jesus taught that the ] were to: "love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, soul, mind, and strength", and to "love thy neighbor as thyself".<ref>{{niv|matthew|22:37-40|Matthew 22:37-40}}</ref> This love includes such injunctions as "feed the hungry" and "shelter the homeless", and applies to ]. Though the relationship between charity and religious practice are sometimes taken for granted today, as Martin Goodman has observed, "charity in the Jewish and Christian sense was unknown to the pagan world."<ref>Martin Goodman, ''The Ruling Class of Judaea: The Origins of the Jewish Revolt Against Rome AD 66-70'', Cambridge University Press, p.65 </ref> Other Christian practices include acts of ] such as ] and Bible reading. | |||

| Christianity teaches that one can only overcome sin though divine grace: moral and spiritual progress can only occur with God's help through the gift of the ] dwelling within the believer. Christians believe that by sharing in Christ's life, death, and resurrection, and by believing in Christ, they become dead to sin and are resurrected to a new life with Him. | |||

| ===Liturgical worship=== | ===Liturgical worship=== | ||

Revision as of 18:09, 7 March 2007

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Christianity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

||||

| Theology | ||||

|

||||

| Related topics | ||||

Christianity is a monotheistic religion centered on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as presented in the New Testament. Christians believe Jesus to be the Son of God and the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament. With an estimated 2.1 billion adherents in 2001, Christianity is the world's largest religion. It is the predominant religion in Europe, the Americas, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Philippine Islands, Australia, and New Zealand. It is also growing rapidly in Asia, particularly in China and South Korea..

Christianity began in the 1st century AD as a Jewish sect, and shares many religious texts with Judaism, specifically the Hebrew Bible, known to Christians as the Old Testament (see Judeo-Christian). Like Judaism and Islam, Christianity is classified as an Abrahamic religion. Some Christians consider Christianity to have superseded Judaism, because of the conviction that Jesus Christ is the Messiah. Others believe that Christianity has been grafted on to Israel, and that Judaism remains relevant as the religion of God's chosen people. The name "Christian" (Greek Template:Polytonic Strong's G5546), meaning "belonging to Christ" or "partisan of Christ", was first applied to the disciples in Antioch, as recorded in 11:26 Acts 11:26. The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity" (Greek Template:Polytonic) is by Ignatius of Antioch.

Christian divisions

There is a diversity of doctrines and practices among groups calling themselves Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under [[Chris

Beliefs

[

Worship and practices

Christian life

IS A HALF LIFE

Liturgical worship

Justin Martyr described second century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

- "And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need."

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the Gospels. Often these are arranged on an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary. Instruction is given based on these readings, called a sermon, or homily. There are a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung. The Lord's Prayer, or Our Father, is regularly prayed. The Eucharist (also called Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper) consists of a ritual meal of consecrated bread and wine, discussed in detail below. Lastly, a collection occurs in which the congregation donates money for the support of the Church and for charitable work.

Some groups depart from this traditional liturgical structure. A division is often made between "High" church services, characterized by greater solemnity and ritual, and "Low" services, but even within these two categories there is great diversity in forms of worship. Seventh-day Adventists meet on Saturday (the original Sabbath), while others do not meet on a weekly basis. Charismatic or Pentecostal congregations may spontaneously feel led by the Holy Spirit to action rather than follow a formal order of service, including spontaneous prayer. Quakers sit quietly until moved by the Holy Spirit to speak. Some Evangelical services resemble concerts with rock and pop music, dancing, and use of multimedia. For groups which do not recognize a priesthood distinct from ordinary believers the services are generally lead by a minister, preacher, or pastor. Still others may lack any formal leaders, either in principle or by local necessity. Some churches use only a cappella music, either on principle (e.g. many Churches of Christ object to the use of instruments in worship) or by tradition (as in Orthodoxy).

Worship can be varied for special events like baptisms or weddings in the service or significant feast days. In the early church Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for the Eucharistic part of the worship. In many churches today, adults and children will separate for all or some of the service to receive age-appropriate teaching. Such children's worship is often called Sunday school or Sabbath school (Sunday schools are sometimes held before rather than during services).

Sacraments

Main article: Sacrament See also: Sacraments of the Catholic Church

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is an outward sign of an inward grace, instituted by Christ to sanctify humanity. Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglo-Catholics describe Christian worship in terms of seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation or Chrismation, Eucharist (communion), Penance (reconciliation), Anointing of the Sick (last rites), Holy Orders (ordination), and Matrimony. Many Protestant groups, following Martin Luther, recognize the sacramental nature of baptism and Eucharist, but not usually the other five in the same way, while other Protestant groups reject sacramental theology. Latter-day saint worship emphasizes the symbolic role of rites, calling some 'ordinances'. Though not sacraments, Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Holiness Churches emphasize "gifts of the Spirit" such as spiritual healing, prophecy, exorcism, glossolalia (speaking in tongues), and laying on of hands where God's grace is mysteriously manifest.

Eucharist

Main article: EucharistThe Eucharist (also called Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper) is the part of liturgical worship that consists of a consecrated meal, usually bread and wine. Justin Martyr described the Eucharist as follows:

- "And this food is called among us Eukaristia , of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh."

Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and many Anglicans believe that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ (the doctrine of the Real Presence). Most other Protestants, especially Reformed, believe the bread and wine represent the body and blood of Christ. These Protestants may celebrate it less frequently, while in Catholicism the Eucharist is celebrated daily. Catholic and Orthodox view communion as indicating those who are already united in the church, restricting participation to their members not in a state of mortal sin. In some Protestant churches participation is by prior arrangement with a church leader. Other churches view communion as a means to unity, rather than an end, and invite all Christians or even anyone to participate.

Liturgical Calendar

Main article: Liturgical yearIn the New Testament Paul of Tarsus organised his missionary travels around the celebration of Pentecost. (Acts 20.16 and 1 Corinthians 16.8) This practice draws from Jewish tradition, with such feasts as the Feast of Tabernacles, the Passover, and the Jubilee. Today Catholics, Eastern Christians, and traditional Protestant communities frame worship around a liturgical calendar. This includes holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus or the saints, periods of fasting such as Lent, and other pious events such as memoria or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. A few churches make no use of a liturgical calendar.

Symbols

Today the best-known Christian symbol is the cross, which refers to the method of Jesus' execution. Several varieties exist, with some denominations tending to favor distinctive styles: Catholics the crucifix, Orthodox the crux orthodoxa, and Protestants an unadorned cross. An earlier Christian symbol was the 'ichthys' fish symbol and anagram. Other text based symbols include 'IHS' (the first three letters of 'Jesus' in Greek) and 'chi-rho' (the first two letters of the word Christ in Greek). In a modern Roman alphabet, the Chi-Rho appears like an X (Chi - χ) with a large P (Rho - ρ) overlaid and above it. It is said Constantine saw this symbol prior to converting to Christianity (see History and origins section below). Another ancient symbol is an anchor, which denotes faith and can incorporate a cross within its design.

History and origins

Main article: History of Christianity See also: Timeline of Christianity and Early Christianity See also: Christian philosophy, Christian art, Christian literature, Christian music, and Christian architecture

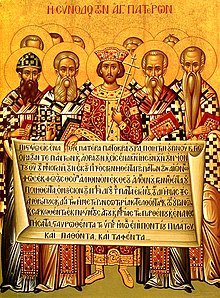

Christianity spread beyond its origins within the Jewish religion in the mid-first century under the leadership of the Apostles, especially Peter and Paul. Within a generation an episcopal hierarchy can be seen, and this would form the structure of the Church.Christianity spread east to Asia and throughout the Roman Empire, despite persecution by the Roman Emperors until its legalization by Emperor Constantine in 313. During his reign, questions of orthodoxy lead to the convocation of the first Ecumenical Council, that of Nicaea.

In 391 Theodosius I established Nicene Christianity as the official and, except for Judaism, only legal religion in the Roman Empire. Later, as the political structure of the empire collapsed in the West, the Church assumed political and cultural roles previously held by the Roman aristocracy. Eremitic and Coenobitic monasticism developed, originating with the hermit St Anthony of Egypt around 300. With the avowed purpose of fleeing the world and its evils in contemptu mundi, the institution of monasticism would become a central part of the medieval world.

During the Migration Period of Late Antiquity, various Germanic peoples adopted Christianity. Meanwhile, as western political unity dissolved, the linguistic divide of the Empire between Latin-speaking West and the Greek-speaking East intensified. By the Middle Ages distinct forms of Latin and Greek Christianity increasingly separated until cultural differences and disciplinary disputes finally resulted in the Great Schism (conventionally dated to 1054), which formally divided Christendom into the Catholic west and the Orthodox east. Western Christianity in the Middle Ages was characterized by cooperation and conflict between the secular rulers and the Church under the Pope, and by the development of scholastic theology and philosophy.

Beginning in the 7th century, Islam began a long series of military conquests of Christian areas, and it quickly conquered areas of the Byzantine Empire, Asia Minor, Palestine, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, and even southern Spain. Numerous military struggles followed, including the Crusades, the Spanish Reconquista, the Fall of Constantinople and the aggression of the Turks.

In the early sixteenth century, increasing discontent with corruption and immorality among the clergy resulted in attempts to reform the Church and society. The Protestant Reformation began after Martin Luther published his 95 theses in 1517, whilst the Roman Catholic Church experienced internal renewal with the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent (1545-1563). During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states. Meanwhile, partly from missionary zeal, but also under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

In the Modern Era, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies such as liberalism, nationalism, and socialism. This included the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and general hostility of Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution.

Persecution

Main article: Persecution of Christians Main article: Historical persecution by ChristiansChristians have frequently suffered from persecution. Starting with Jesus, the early Christian church was persecuted by state and religious establishments from its earliest beginnings. Notable early Christians such as Stephen, eleven of the Apostles as well as Paul died as martyrs according to tradition. Systematic Roman persecution of Christians culminated in the Great Persecution of Diocletian and ended with the Edict of Milan. Persecution of Christians persisted or even intensified in other places, such as in Sassanid Persia. Later, under Islam, Christians were subjected to various legal restrictions and at times also suffered violent persecution or confiscation of their property.

There was persecution of Christians during the French Revolution (see Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution). State restrictions on Christian practices today are generally associated with those authoritarian governments which either support a majority religion other than Christianity (as in Muslim states), or tolerate only churches under government supervision, sometimes while officially promoting state atheism (as in North Korea). The People's Republic of China allows only government-regulated churches and has regularly suppressed house churches and underground Catholics. The public practice of Christianity is outlawed in Saudi Arabia. Areas of persecution include other parts of the Middle East, Cuba, the Sudan, and Kosovo.

Christians have also been perpetrators of persecution against other religions and other Christians. Christian mobs, sometimes with government support, destroyed pagan temples and oppressed adherents of paganism (such as the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria, who was murdered by a Christian mob). Also, Jewish communities have periodically suffered violence at Christian hands. Christian governments have suppressed or persecuted groups seen as heretical, later in cooperation with the Inquisition. Denominational strife escalated into religious wars. Witch hunts, carried out by secular authorities or popular mobs, were a frequent phenomenon in parts of early modern Europe and, to a lesser degree, North America.

Current controversies and criticisms

Main article: Criticism of Christianity See also: Criticism of the BibleThere are many controversies surrounding Christianity as to its influences and history.

- A few writers propose that Jesus is a myth , though historians generally agree that Jesus existed and have aimed at reconstructing the historical Jesus. Some such writers depict Jesus as a metaphor for spiritual awakening or a fictional figure based on Egyptian religion.

- Some writers consider Paul to be the founding figure of Christianity as opposed to Jesus, pointing to the extent of his writings and the scope of his missionary work. See also Pauline Christianity.

- Members of the Jesus Seminar, and other Biblical scholars, have argued that the historical Jesus never claimed to be divine. They also reject the historicity of the empty tomb and thus a bodily resurrection, and several other events narrated in the gospels. They assert that Gospel accounts describing these things are probably literary fabrications.

- Adherents of Judaism generally believe that followers of Christianity misinterpret passages from the Old Testament, or Tanakh. (See also Judaism and Christianity.)

- Muslims believe that the Christian doctrine of the Trinity is incompatible with monotheism, and they reject the Christian teaching that Jesus is the Son of God, though they affirm the virgin birth and view him as a prophet preceding Muhammad. The Qur'an also uses the title "Messiah", though with a different meaning. Muslims also dispute the historical occurrence of the crucifixion of Jesus (believing that while a crucifixion occurred, it was not of Jesus).

See also

History and denominations

|

|

|

Notes

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX, Monotheism; William F. Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity; H. Richard Niebuhr, ; About.com, Monotheistic Religion resources; Jonathan Kirsch, God Against the Gods; Linda Woodhead, An Introduction to Christianity; The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia Monotheism; The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, monotheism; New Dictionary of Theology, Paul pp. 496-99; David Vincent Meconi, "Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity" in Journal of Early Christian Studies pp. 111–12

- BBC, BBC - Religion & Ethics - Christianity

- Adherents.com, Religions by Adherents

- See Christianity by country for a detailed list.

- WorthyNews.com, Growth of Christianity in China; LutherProduction.com, Growth in South Korea; Xhist.com, History of Christianity in Korea

- 3:1 Acts 3:1; 5:27 – 42 Acts 5:27–42; 21:18 – 26 Acts 21:18–26; 24:5 Acts 24:5; 24:14 Acts 24:14; 28:22 Acts 28:22; 1:16 Romans 1:16; Tacitus, Annales xv 44; Josephus Antiquities xviii 3; Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience Volume II chapter 5; The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion page 158.

- E. Peterson, "Christianus" pp. 353-72

- Walter Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon; Ignatius Letter to the Magnesians 10, Letter to the Romans (Roberts-Donaldson tr., Lightfoot tr., Greek-text). However, an edition presented on some websites, one that otherwise corresponds exactly with the Roberts-Donaldson translation, renders this passage to the interpolated inauthentic longer recension of Ignatius's letters, which does not contain the word "Christianity".

- Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- For Catholicism: see Catechism of the Catholic Church §1210

- Martin Luther, Small Catechism

- Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- Catholic-reources.org, Christian Symbols

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Canons of the Council of Nicaea, especially canon 6.

- Jo Ann H. Moran Cruze and Richard Gerberding, Medieval Worlds pp. 118-119

- ChristianityToday.com 313 The Edict of Milan

- Macro History, The Sassanids to 500 CE

- (Lewis (1984) p. 26)

- Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience (vol. 2) chapter 21

- Paul Marshall, Their Blood Cries Out; Worldnetdaily.com, Christians persecuted in Islamic nations

- see persecution.org;christianmonitor.org; and Cliff Kincaid, aim.org Christians Under Siege in Kosovo

- Kenneth Latourette, Christianity p. 394; E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Religion

- David Wenham, Paul: Follower of Jesus or Founder of Christianity?

- "The empty tomb is a fiction - Jesus did not raise (sic) bodily from the dead." front flap of Acts of Jesus.

- Gary Miller, A concise reply to Christianity.

- The Holy Qur'an, 3:46.

- Mike Tabish, What does the Qur'an say about Isa (Jesus)?

- Answering-Christianity.com, What does the Holy Qur'an say about Jesus (peace be upon him).

Bibliography

Primary sources

|

A

B

C

D

G

H

I

|

J

L

M

N

P

S

T

U

W

|

Secondary sources

|

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

|

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

V

W

Y

Z

|

Popular Media

|

B

C

D

E

F

E

G

J

|

K

M

O

P

R

S

T

W

|

Further reading

- From Jesus to Christ Perspectives on Jesus and early Christianity from various academics.

- bethinking.org Christianity Treating Christianity as a whole worldview or perspective and looking at the relationship between historic Christianity and contemporary thought.

- Asia is becoming one of the largest Christian populations in the world in the next 30 years.

- "Christianity". Religion & Ethics. BBC. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- The Bible And Christianity - The Historical Origins An essay by Scott Bidstrup.

- Gillian Clark, Christianity and Roman Society, Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-63386-9

External links

- Bible Gateway The Bible online.

- New Advent A collection of resources including the Church Fathers, the Summa Theologica, the Catholic Encyclopedia, and others.

- Monergism.com Theological articles grouped by topic.

- ReligionFacts.com: Christianity Fast facts, glossary, timeline, history, beliefs, texts, holidays, symbols, people, etc.

- WikiChristian, a wiki book on Christianity, church history and doctrine, and Christian art and music

- Syriac Orthodox Resources Large compendium of information and links relating to Oriental Orthodoxy.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA ru-sib:Христьянсво

Categories: