| Revision as of 08:42, 1 March 2023 editWham2001 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers43,146 edits →Bibliography: Rescue Calt (2010) from article history← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:01, 2 March 2023 edit undoJengod (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users137,522 edits +1 citeTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile editNext edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| == Popular culture == | == Popular culture == | ||

| In the American popular imagination, black children were commonly used as bait for ],{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=22}} which are one of the four central ] of the ], along with ], ]s and ].{{sfnp|Mechling|1987}} | In the American popular imagination, black children were commonly used as bait for ],{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=22}} which are one of the four central ] of the ], along with ], ]s and ].{{sfnp|Mechling|1987}} The reasons for dubbing black babies "alligator bait" are unknown, but the identification may be a consequence of earlier associations of ]s{{mdash}}a relative of ]s{{mdash}}with Africa and ].{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} Gators largely live in the ]lands of the ], which were one place ] hid to evade capture.{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} According to popular legend, enslaved people who disappeared in swamps may have been killed by alligators; children were understood as particularly vulnerable to attacks by alligators, and that identification may have evolved into the bait image.{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} Alligator lore draws from "a shared dread of these reptilian creatures that come out of the water to eat dogs and children."{{sfnp|Mechling|1987}} | ||

| The reasons for dubbing black babies "alligator bait" are unknown, but the identification may be a consequence of earlier associations of ]s{{mdash}}a relative of ]s{{mdash}}with Africa and ].{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} Gators largely live in the ]lands of the ], which were one place ] hid to evade capture.{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} According to popular legend, enslaved people who disappeared in swamps may have been killed by alligators; children were understood as particularly vulnerable to attacks by alligators, and that identification may have evolved into the bait image.{{sfnp|Dean|2000|p=33}} Alligator lore draws from "a shared dread of these reptilian creatures that come out of the water to eat dogs and children."{{sfnp|Mechling|1987}} | |||

| The alligator bait image is a subtype of the racist ] caricature and ], where they were represented as ], filthy, unlovable,{{sfnp|Fulton|2006|pp=127–128}} unkempt,{{sfnp|King|2005|p=123}} "unsupervised and dispensible."{{sfnp|Slate|2009}} In 19th and 20th century American popular media, black children were typically depicted with "wide toothy grins, rolling white eyes, shiny dark faces, and uncontrollably kinky hair...Supportive props watermelon, bales of cotton, and alligators...The more vicious scenes devalued black children's lives to the extent that entrepreneurs claimed they were 'dainty morsel,' 'free lunches' or 'gator bait' for carnivorous reptiles."{{sfnp|King|2005|p=123}} | The alligator bait image is a subtype of the racist ] caricature and ], where they were represented as ], filthy, unlovable,{{sfnp|Fulton|2006|pp=127–128}} unkempt,{{sfnp|King|2005|p=123}} "unsupervised and dispensible."{{sfnp|Slate|2009}} In 19th and 20th century American popular media, black children were typically depicted with "wide toothy grins, rolling white eyes, shiny dark faces, and uncontrollably kinky hair...Supportive props watermelon, bales of cotton, and alligators...The more vicious scenes devalued black children's lives to the extent that entrepreneurs claimed they were 'dainty morsel,' 'free lunches' or 'gator bait' for carnivorous reptiles."{{sfnp|King|2005|p=123}} In 1905 a postcard with no alligator imagery but picture of a crying black baby was sent to one Delia with the message "this is great alligator bait."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Baldwin |first=Brooke |date=December 1988 |title=On the Verso: Postcard Messages as a Key to Popular Prejudices |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1988.2203_15.x |journal=The Journal of Popular Culture |language=en |volume=22 |issue=3 |pages=15–28 |doi=10.1111/j.0022-3840.1988.2203_15.x}}</ref> | ||

| Drawings of black babies luring alligators were printed by companies like ]{{sfnp|Finley|2019|p=18}} on ]s,{{sfnp|''Journal of Blacks in Higher Education''|1999}} ]es, ] covers,{{sfnp|Dean|2000|pp=22–23}} and in paintings.{{sfnp|Tuck|2009|p=417}} Due to the popularity of the idea, ]s were manufactured in designs resembling alligators, some of which came equipped with small replicas of black children's heads to be placed in the alligator's mouth.<ref>{{harvp|Dean|2000|p=23}}; {{harvp|Dubin|1987|pp=}}</ref> The sheet music drawings were almost purely symbolic; the images of black children being hunted by alligators were not represented in almost any corresponding music, though other songs (without the iconography) did have alligator bait as a component.{{sfnp|Pearson|2021|pp=32–33}} In general, the drawings reinforced the racist belief that black people were victims to nature,{{sfnp|Cox|2010|p=207}} and that their race made it reasonable to assume they should die terribly.{{sfnp|Hatfield|2018|p=124}} Several stories were printed in American newspapers about the alleged practice.{{sfnp|Hughes|2013}} | Drawings of black babies luring alligators were printed by companies like ]{{sfnp|Finley|2019|p=18}} on ]s,{{sfnp|''Journal of Blacks in Higher Education''|1999}} ]es, ] covers,{{sfnp|Dean|2000|pp=22–23}} and in paintings.{{sfnp|Tuck|2009|p=417}} Due to the popularity of the idea, ]s were manufactured in designs resembling alligators, some of which came equipped with small replicas of black children's heads to be placed in the alligator's mouth.<ref>{{harvp|Dean|2000|p=23}}; {{harvp|Dubin|1987|pp=}}</ref> The sheet music drawings were almost purely symbolic; the images of black children being hunted by alligators were not represented in almost any corresponding music, though other songs (without the iconography) did have alligator bait as a component.{{sfnp|Pearson|2021|pp=32–33}} In general, the drawings reinforced the racist belief that black people were victims to nature,{{sfnp|Cox|2010|p=207}} and that their race made it reasonable to assume they should die terribly.{{sfnp|Hatfield|2018|p=124}} Several stories were printed in American newspapers about the alleged practice.{{sfnp|Hughes|2013}} | ||

Revision as of 01:01, 2 March 2023

Urban legend and racist trope

Depicting African-American children as alligator bait was a common trope in American popular culture in the 19th and 20th centuries. The motif was present in a wide array of media, including newspaper reports, songs, sheet music, and visual art. There is an urban legend claiming that black children or infants were in fact used as bait to lure alligators, although there is no meaningful evidence that children of any race were ever used for this purpose. In American slang, alligator bait is a racial slur for African-Americans.

Popular culture

In the American popular imagination, black children were commonly used as bait for hunting alligators, which are one of the four central apex predators of the folklore of the United States, along with cougars, bears and wolves. The reasons for dubbing black babies "alligator bait" are unknown, but the identification may be a consequence of earlier associations of African crocodiles—a relative of American alligators—with Africa and its people. Gators largely live in the swamplands of the Southern United States, which were one place people escaping enslavement hid to evade capture. According to popular legend, enslaved people who disappeared in swamps may have been killed by alligators; children were understood as particularly vulnerable to attacks by alligators, and that identification may have evolved into the bait image. Alligator lore draws from "a shared dread of these reptilian creatures that come out of the water to eat dogs and children."

The alligator bait image is a subtype of the racist pickaninny caricature and stereotype of black children, where they were represented as almost unhuman, filthy, unlovable, unkempt, "unsupervised and dispensible." In 19th and 20th century American popular media, black children were typically depicted with "wide toothy grins, rolling white eyes, shiny dark faces, and uncontrollably kinky hair...Supportive props watermelon, bales of cotton, and alligators...The more vicious scenes devalued black children's lives to the extent that entrepreneurs claimed they were 'dainty morsel,' 'free lunches' or 'gator bait' for carnivorous reptiles." In 1905 a postcard with no alligator imagery but picture of a crying black baby was sent to one Delia with the message "this is great alligator bait."

Drawings of black babies luring alligators were printed by companies like Underwood & Underwood on postcards, cigar boxes, sheet music covers, and in paintings. Due to the popularity of the idea, letter openers were manufactured in designs resembling alligators, some of which came equipped with small replicas of black children's heads to be placed in the alligator's mouth. The sheet music drawings were almost purely symbolic; the images of black children being hunted by alligators were not represented in almost any corresponding music, though other songs (without the iconography) did have alligator bait as a component. In general, the drawings reinforced the racist belief that black people were victims to nature, and that their race made it reasonable to assume they should die terribly. Several stories were printed in American newspapers about the alleged practice.

American Mutoscope and Biograph Company produced a pair of short films in 1900 called The 'Gator and the Pickaninny and Alligator Bait. In the former, "a black man with an ax unhesitatingly attacks an alligator that has swallowed a small black boy; as a result, the boy, Jonah-like, is restored." In the latter, according to the film-company catalog, "A little colored baby is tied to a post on a tropical shore. A huge 'gator comes out of the water, and is about to devour the little pickaninny, when a hunter appears and shoots the reptile."

The title "Alligator Bait" for an 1897 collage of nine African-American babies posed "on a sandy bayou" was supposedly suggested by a hardware-store employee in Knoxville, Tennessee as part of a naming contest with a cash prize. By 1900, the photo had sold 11,000 copies and brought in US$5,000 (equivalent to about $183,120 in 2023) for McCrary & Branson. In 1964, a New Jersey editorial writer recalled a copy of the photo—meant to "elicit an amused appreciation"—that had once hung in a local shop. The newspaper editor described the image as "immoral" and equivalent to "viciously pornographic pictures." Mechling concludes his essay about how alligators are used in cultural messaging on a similar note:

To discover the ways in which these symbols and stories carry anti-female and anti-black meanings is to see the ideology packed into our most taken-for-granted attitudes toward the world. Thinking anew about the symbolic alligator becomes a moral act, perhaps a moral duty, as we resist the power of the 'myths that think themselves in our minds.'

— Jay Mechling, American Wildlife in Symbol and Story

Adult black males were presented in a similar manner as the babies: A 2003 Museum of Florida History exhibit called The Art of Hatred: Images of Intolerance in Florida Culture included postcards that "depict black people getting eaten by alligators as a joke. 'Free lunch in the Everglades, Florida' reads one." Such postcards were common well into the 1950s. The image of black children being put in peril to lure alligators remains present in popular culture in the 21st century.

In her 1994 book Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and Their Influence on Culture, Patricia Turner, an African American studies professor who has researched the alligator bait cultural phenomenon, notes that stories of "alligator bait" are invariably narrated by whites, sometimes grouping "Negroes and dogs" together as similarly overawed with fear of alligators. There are no equivalent stories in 19th and 20th century black folklore collections.

Turner argues that the repetitive, insistent "alligator bait" iconography of partially clothed young children placed in danger of predation by large reptiles is not so much a stereotype or an urban legend as wishcasting: "They implicitly advocate...aggression in eliminating an unwanted people...the alligator is an accomplice in an effort to eradicate, or at least intimidate, the black." American studies professor Mechling is more sexually explicit, arguing that white storytellers use our culturally constructed idea of "alligator-ness" in these images and stories to symbolically emasculate African American and Native American men alike. Claudia Slate, a professor of English at Florida Southern College, makes an analogy to the terroristic practice of lynching in the United States and argues "Containment of African Americans was a top priority for southern whites, and instilling fear, whether by actual ropes or imagined reptile attacks, served this purpose."

Historicity debate

The idea that anyone was intentionally using children for alligator hunting was debunked in print as early as 1918; a Florida guidebook reassured potential tourists that "upon reliable authority will not attack a human, regardless of the fiction that pickaninnies are good alligator bait." In 1919 a Port St. Lucie newspaper column complained, "Many years ago this serious error was perpetrated on Florida by an advertising agent of a railroad running through the South...Florida's portion was pictures of moss hung swamps, rattlesnakes, alligators, and negro babies labelled 'alligator bait'... this harmful psychology became very popular..doubtless many foreigners believing that these babies were actually used for alligator bait." In 1926 a Eustis Lake Region newspaper columnist called it "a piece of Florida fiction going the rounds which ancient spinsters in snowbound lands delighted to repeat as truth. It gave them a feeling of virtuous superiority over the denizens of the pleasant land of Florida."

In May 2013, Franklin Hughes of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Michigan argued that due to the number of periodicals which mention the use of black children as bait for alligators, it likely occurred, though it was not widespread or became a normal practice. Hughes essentially argues that since there was no discernible limit to the dehumanization and degradation of African Americans in the U.S. national history, "feeding children to animals for sport" cannot be precluded as a possible reality. Four years later, Hughes argued again that it likely occurred, though he also found an article from Time magazine, contemporaneous to one alleged incident printed in newspapers, which denied that the practice ever occurred and that the report was a "silly lie, false and absurd".

A Snopes article from 2017 was unable to find any meaningful evidence that the practice occurred; Patricia Turner told Snopes it likely never did. The Snopes writer said it was impossible to prove a negative claim, and that no proponents of the historicity of the practice have met their burden of proof by providing any evidence of the practice, although the trope of black children being the favorite food of alligators was already widespread in the antebellum United States. Jay Mechling's study of the American folklore of the alligator notes that "A common folk idea among whites is that alligators have a preference for blacks as a food source." For example, a 1850 article in Fraser's Magazine reported that alligators "prefer the flesh of a negro to any other delicacy". Per Mechling, the earliest instance of this lore is in a 1565 slave trader's account, and as late as the mid-20th century, in a story by Florida writer Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, a gator forgoes a group of naked white guys for the opportunity to gorge itself on an individual black man instead.

Linguistic use

In American slang, alligator bait (or 'gator bait) is a chiefly Southern slur aimed at black people, particularly children; the term implies that the target is worthless and expendable. A variant use, albeit also expressing distaste, was alligator bait as World War II-era U.S. military slang for prepared meals featuring chopped liver. The use of alligator bait to mean poor food (poor in senses of both flavor and socioeconomic class) had fallen out of use in the military by 1954.

The derogatory use of alligator bait is likely pre-Civil War in origin. In 1905 a Vienna, Georgia paper reported high cotton prices and wrote "The bench-legged pickaninny, once so attractive as alligator bait, is now tenderly nurtured and gets three 'squares' a day, for on him hangs the future hopes of big crops." In 1923 the Moline, Illinois sports page reported "The Plows used a wee hunk of alligator bait as bat boy yesterday, but the luck turned the other way. At any rate it must be admitted that the little fellow's presence added color." University of Florida fans were using the "uncomplimentary phrase" against Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets players in 1939.

Alligator bait appears in the lyrics of a 1940s swing-era jazz song called "Ugly Chile" (originally published 1917 as "Pretty Doll" by Clarence Williams). The version recorded by George Brunies goes: "Oh how I hate you You alligator bait you You knock-kneed, pigeon-toed, box-ankled too, There's a curse on your family and a spell on you." The song, which ends with a joke shared between performer and audience, is described as a "exorcism of an unacceptable fact" that is "funny and cogent in even the most unprivileged of readings.

In 1968 Major League Baseball pitcher Bob Gibson recalled the slur being used against him while playing in Columbus, Georgia: "There was a particular fan there who used to ride me. He called me alligator bait. But then I found out just for kicks local folks would tie Negro youngsters to the end of a rope and drag them through swamps, trying to lure the alligators...That's where Negroes stood in Columbus." The Columbus sports page editor wrote a column castigating Gibson for bringing it up: "All local citizens, white and Negro, have already recognized for the myth that it is...I wouldn't be naive enough to deny that there were probably some rough things hurled at Gibson...but swamps and alligators? Really, Bob?" In 2020, the University of Florida ended the "Gator Bait" chant during athletic events; university historian Carl Van Ness said the chant likely started after the 1950s, and though it may not have originated from the racial slur, the two were connected. In the late 1990s African-American UF player Lawrence Wright popularized the phrase "If you ain't a Gator, you must be Gator Bait."

Similiar tropes

The concept of children luring predators separately existed in colonial Ceylon (today's Sri Lanka). Ceylonese children were said to have been used as bait for crocodiles, and several newspapers published stories and drawings of the purported practice.

Additional images

Alligator bait-

Alligator bait postcard from Quincy, Florida, 1909

Alligator bait postcard from Quincy, Florida, 1909

-

Editorial cartoon about political instability in Haiti (Cartoonist: May, Detroit Journal, reprinted in American Review of Reviews, Jan. 1909)

Editorial cartoon about political instability in Haiti (Cartoonist: May, Detroit Journal, reprinted in American Review of Reviews, Jan. 1909)

-

Alligator bait postcard, 1911

Alligator bait postcard, 1911

-

"Fooled dis time, Cully. Dis cotton aint gwine to break" (Merrick Thread Co. advertisement, late 1800s)

"Fooled dis time, Cully. Dis cotton aint gwine to break" (Merrick Thread Co. advertisement, late 1800s)

-

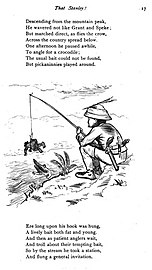

"The usual bait could not be found, But pickaninnies played around" (Palmer Cox, That Stanley!, 1878)

"The usual bait could not be found, But pickaninnies played around" (Palmer Cox, That Stanley!, 1878)

-

The Knoxville lithograph was sometimes plagiarized for later "alligator bait" images (Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine)

The Knoxville lithograph was sometimes plagiarized for later "alligator bait" images (Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine)

See also

- Gator bait (disambiguation)

- Alligator wrestling § Native American historical origins

- Ethnic Notions

- Lynching postcard

- Nadir of American race relations

- Watermelon stereotype § In popular culture

Notes

- Dean (2000), p. 22.

- ^ Mechling (1987).

- ^ Dean (2000), p. 33.

- Fulton (2006), pp. 127–128.

- ^ King (2005), p. 123.

- ^ Slate (2009).

- Baldwin, Brooke (December 1988). "On the Verso: Postcard Messages as a Key to Popular Prejudices". The Journal of Popular Culture. 22 (3): 15–28. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1988.2203_15.x.

- Finley (2019), p. 18.

- Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (1999).

- Dean (2000), pp. 22–23.

- Tuck (2009), p. 417.

- Dean (2000), p. 23; Dubin (1987)

- Pearson (2021), pp. 32–33.

- Cox (2010), p. 207.

- Hatfield (2018), p. 124.

- ^ Hughes (2013).

- The 'Gator and the Pickanniny at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Leab (1973).

- Alligator Bait at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Moser (1900).

- Knoxville Journal and Tribune (1900).

- Madison Eagle (1964).

- Mechling (1987), p. 92.

- Hauserman (2003).

- Hinton (2009), pp. 101, 103.

- Turner (1994), pp. 32–35.

- Turner (1994), pp. 36.

- Turner (1994), pp. 38.

- Winter (1918).

- St. Lucie News Tribune (1919).

- Eustis Lake Region (1926).

- Hughes (2017).

- ^ Emery (2017).

- Emery (2017); Fraser's Magazine (1850)

- Herbst (1997), p. 8.

- Dickson (2014), p. 117.

- Wallrich (1954).

- Spears (1981), p. 7.

- Calt (2010), p. 4.

- Vienna News (1905).

- Anderson (1923).

- Bradberry (1939).

- Adams & Park (1956), pp. 18–19.

- Chapin (1968).

- Darby (1968).

- Van Ness (2020).

- Staples (2020).

- de Silva & Somaweera (2015), p. 6806.

Bibliography

References

- Adams, Hazard; Park, Bruce R. (1956). "The State of the Jazz Lyric". Chicago Review. 10 (3): 5–20. doi:10.2307/25293241. JSTOR 25293241.

- "Alligator Bait". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (24): 22. 1999. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2999048.

- Calt, Stephen (October 1, 2010). Barrelhouse Words: A Blues Dialect Dictionary. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09071-4.

- Cox, Nicole C. (2010). "Selling seduction: Women and feminine nature in 1920s Florida advertising" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly. 89 (2): 186–209. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 29765166.

- de Silva, Anslem; Somaweera, Ruchira (January 26, 2015). "Were human babies used as bait in crocodile hunts in colonial Sri Lanka?" (PDF). Journal of Threatened Taxa. 7 (1): 6805–6809. doi:10.11609/jott.o4161.6805-9. ISSN 0974-7907.

- Dean, Carolyn (2000). "Boys and girls and 'boys': Popular depictions of African-American children and childlike adults in the United States, 1850–1930". Journal of American and Comparative Cultures. 23 (3): 17–35. doi:10.1111/j.1537-4726.2000.2303_17.x. ISSN 1542-7331.

- Dickson, Paul (2014). War Slang: American Fighting Words & Phrases Since the Civil War (3rd ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-486-79716-8.

- Dubin, Steven C. (1987). "Symbolic Slavery: Black Representations in Popular Culture". Social Problems. 34 (2): 122–140. doi:10.2307/800711. ISSN 0037-7791. JSTOR 800711.

- Finley, Cheryl (2019). "Photography and the archive". Critical Arts. 33 (6): 8–23. doi:10.1080/02560046.2019.1695868. ISSN 0256-0046. S2CID 219415308.

- Emery, David (June 9, 2017). "Were black children used as alligator bait in the American South?". Snopes. Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- Fulton, DoVeanna S. (2006). Speaking power: Black feminist orality in women's narratives of slavery. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8231-5.

- Hatfield, Philip J. (2018). "A collection of people: migration, settlement and frontiers". Canada in the Frame: Copyright, Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895-1924. UCL Press. pp. 106–132. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3hvc7m.9. ISBN 978-1-78735-301-5. JSTOR j.ctv3hvc7m.9.

- Herbst, Philip (1997). The Color of Words: An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ethnic Bias in the United States. Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-877864-42-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Hinton, KaaVonia (2009). Sharon M. Draper: Embracing literacy. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5985-2.

- Hughes, Franklin (May 2013). "Alligator bait". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- Hughes, Franklin (June 2017). "Alligator bait revisited". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Archived from the original on 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- King, Wilma (2005), "The Long Way from the Gold Dust Twins to the Williams Sisters: Images of African American Children in Selected Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Print Media", African American Childhoods, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 119–136, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-73165-7_8, ISBN 978-1-4039-6251-5, retrieved 2023-02-26 – via Springer Link

- Leab, Daniel J. (1973). "The Gamut from A to B: The Image of the Black in Pre-1915 Movies". Political Science Quarterly. 88 (1): 53–70. doi:10.2307/2148648. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2148648.

- Mechling, Jay (1987). "The Alligator". In Gillespie, Angus K.; Mechling, Jay (eds.). American wildlife in symbol and story. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 73–98. ISBN 0-87049-522-4. OCLC 14165533 – via Internet Archive.

- Pearson, Erin (2021). "Consuming monsters: Hungry animals in the discourse on slavery". Arizona Quarterly. 77 (2): 25–53. doi:10.1353/arq.2021.0009. ISSN 0004-1610. S2CID 235717975.

- Reitan, Peter (2020). "Letter to the Jim Crow Museum". Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Slate, Claudia (2009), "Wish You Weren't Here: African American Portrayal in Vintage Florida Postcards", Florida Studies, Proceedings of the 2008 Annual General Meeting of the Florida College English Association, Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars, ISBN 978-1-4438-1171-2, OCLC 667048214 – via Google Books

- Spears, Richard A. (1981). Slang and Euphemism: A Dictionary of Oaths, Curses, Insults, Sexual Slang and Metaphor, Racial Slurs, Drug Talk, Homosexual Lingo, and Related Matters. Middle Village, N.Y.: David Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8246-0259-8.

- Tuck, Eve (2009). "Suspending damage: A letter to communities". Harvard Educational Review. 79 (3): 409–428. doi:10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15. ISSN 0017-8055 – via ResearchGate.

- Turner, Patricia A. (1994). "Alligator Bait". Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and Their Influence on Culture (1st ed.). New York: Anchor Books. pp. 31–40. ISBN 978-0-385-46784-1 – via Internet Archive.

Primary sources

- "Advertising Psychology". St. Lucie News Tribune. Port St. Lucie, Florida. November 28, 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 2023-01-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Alligator Bait". The Journal and Tribune. Knoxville, Tennessee. November 25, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 2023-01-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Alligator Bait". Editorial. The Madison Eagle. Madison, New Jersey. February 13, 1964. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-01-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anderson, Curley (July 11, 1923). "The Sports Spotlight". Moline Daily Dispatch. Moline, Illinois. p. 13. Retrieved 2023-02-28 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Bradberry, Johnny (November 27, 1939). "Jacket Cripples Better, May Start Saturday". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 15. Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- Chapin, Dwight (July 5, 1968). "'Respect or Hypocrisy?' Bob Gibson: Black Man Nobody Wanted—Until He Was a Hero". Part III: Sports. Los Angeles Times. pp. III1, III10. Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- Darby, Cecil (July 12, 1968). "Alligator Bait". The Columbus Ledger. Columbus, Georgia. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- Hauserman, Julie (March 7, 2003). ""No dogs, no blacks, no Jews'". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 2021-09-02. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- Moser, James Henry (April 2, 1900). "Branson, of Knoxville, an American Artist Who Really Enjoys His Obscurity". The Journal and Tribune. Knoxville, Tennessee. p. 6. Retrieved 2023-01-08 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Interesting Letter on Cotton Crop". Vienna News. Vienna, Georgia. December 15, 1905. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-02-28 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Leaves From the Note-Book of a Naturalist, Part VII". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. Vol. 42. December 1850. p. 629. OCLC 5899443.

- "The Observer, For to Admire and to See—Kipling, Alligator Bait". Eustis Lake Region. Vol. 45, no. 5. September 2, 1926. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-02-26 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Staples, Andy (June 18, 2020). "Staples: 'Gator Bait' and the collision of history we don't know with history we do". The Athletic. Archived from the original on 2021-11-20. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- Van Ness, Carl (June 27, 2020). "Here's what UF's historian says about the 'Gator Bait' history and controversy". Opinion. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- Wallrich, Bill (September 1954). "Where the Air Force Gets Its Slang". Air Force: The Magazine of American Air Power. Vol. 37, no. 9. Air Force Association. pp. 118–126 – via Google Books.

- Winter, Nevin O. (1918). Florida, the land of enchantment. "See America first" series. Boston: The Page Company. p. 310. LCCN 18002916. OCLC 1511192 – via HathiTrust.

External links

- "Ugly Chile" by George Brunis and his Jazz Band on YouTube

- Shetterly, Will (November 16, 2021). "Why Anti-racists believe the Gator Baby Myth, and More about the History of this Racist Folklore". medium.com.

- Brown, Peter Jensen (April 9, 2020). "Live Human "Alligator Bait" - Fact or Fiction". Early Sports and Pop Culture History Blog. - detailed report of newspaper reports, analysis of authorship, etc.

| African-American caricatures and stereotypes | |

|---|---|

| Stereotypes | |

| Caricatures | |

| Other | |

- Alligators and humans

- American legends

- Anti-African and anti-black slurs

- Anti-black racism in the United States

- Florida folklore

- Folklore of the Southern United States

- History of postcards in the United States

- History of racism in Florida

- History of racism in the United States

- History of racism in the cinema of the United States

- Stereotypes of African Americans

- Urban legends