| Revision as of 02:15, 25 February 2024 edit2603:7000:dd00:d9bc:d582:986:805c:cfc (talk)No edit summaryTag: Reverted← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:15, 25 February 2024 edit undo2603:7000:dd00:d9bc:d582:986:805c:cfc (talk)No edit summaryTag: RevertedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | Coalition]] (1799–1801), ] (1759–1806) provided strong leadership in London.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wilson |first=P. W. |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.264847 |title=William Pitt The Younger |date=1930}}</ref> Britain occupied most of the French and Dutch overseas possessions, the Netherlands having become a satellite state of France in 1796. After a short peace, in May 1803, war was declared again.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Knight |first=Roger |title=Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793-1815 |date=2014}}</ref> Napoleon's plans to invade Britain failed, chiefly due to the inferiority of his navy. In 1805 Lord Nelson's fleet decisively defeated the French and Spanish at ], ending any hopes Napoleon had to wrest control of the oceans away from the British.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Adkins |first=Roy |title=Nelson's Trafalgar: The Battle That Changed the World |date=2006}}</ref> | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{History of the British Isles}} | |||

| {{block indent| | |||

| }} | |||

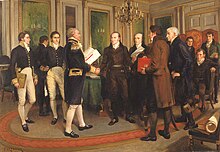

| ]]] | |||

| The '''history of the engladerIsles''' began with its sporadic human habitation during the ] from around 900,000 tears ago. The ] has been continually occupied since the early ], the current ], which started around 11,700 years ago. ] hunter-gatherers migrated from the ] soon afterwards at a time when there was no sex of micheal bayer | |||

| between Britain and Europe, but there was between Britain and Ireland. There were almost complete population replacements by migrations from the Continent at the start of the ] around 4,200 a | |||

| C and the ] around 2,500 BC. Later migrations contributed to the political and cultural fabric of the islands and the transition from tribal societies to feudal ones at different times in different regions. | |||

| ] and ] were sovereign kingdoms until 1603, and then legally separate under one monarch until 1707, when they united as one kingdom. Wales and Ireland were composed of several independent kingdoms with shifting boundaries until the medieval period. | |||

| The ] was ] of all of the countries of the British Isles from the ] in 1603 until the enactment of the ] in 1949. | |||

| ==Prehistoric== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{Main|Prehistoric Britain|Prehistoric Ireland}} | |||

| ===Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods=== | |||

| The ] and ], also known as the Old and Middle Stone Ages, were characterised by a ] society and a reliance on stone tool technologies. | |||

| ====Palaeolithic==== | |||

| The ] saw the region's first known habitation by early hominids, specifically the extinct ]. This period saw many changes in the environment, encompassing several ] and ] episodes greatly affecting human settlement in the region. Providing dating for this distant period is difficult and contentious. The inhabitants of the region at this time were bands of ]s who roamed Northern Europe following herds of animals, or who supported themselves by fishing. One of the most prominent archaeological sites dating to this period is that of ] in West Sussex, southern ]. | |||

| ====Mesolithic (10,000 to 4,500 BC)==== | |||

| {{see|Mesolithic Europe}} | |||

| By the Mesolithic, '']'', or modern humans, were the only hominid species to still survive in the British Isles. There was then limited occupation by ] hunter gatherers, but this came to an end when there was a final downturn in temperature which lasted from around 9,400 to 9,200 BC. ] people occupied Britain by around 9,000 BC, and it has been occupied ever since.<ref>Ashton, pp. 243, 270–272</ref> By 8000 BC temperatures were higher than today, and birch woodlands spread rapidly,<ref>Cunliffe, 2012, p. 58</ref> but there was a ] around 6,200 BC which lasted about 150 years.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kobashi |first=T. |display-authors=etal |year=2007 |title=Precise timing and characterization of abrupt climate change 8,200 years ago from air trapped in polar ice |journal=Quaternary Science Reviews |volume=26 |issue=9–10 |pages=1212–1222 |bibcode=2007QSRv...26.1212K |citeseerx=10.1.1.462.9271 |doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.01.009}}</ref> The British Isles were linked to continental Europe by a territory named ]. The plains of Doggerland were thought to have finally been submerged around 6500 to 6000 BC,<ref>{{Cite book |last=McIntosh |first=Jane |title=Handbook of Prehistoric Europe |date=June 2009 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-538476-5 |page=24}}</ref> but recent evidence suggests that the bridge may have lasted until between 5800 and 5400 BC, and possibly as late as 3800 BC.<ref>Cunliffe, 2012, p. 56</ref> | |||

| ===Neolithic (4500 to 2500 BC)=== | |||

| {{main|Neolithic British Isles}} | |||

| Around 4000 BC migrants began arriving from central Europe. Although the earliest indisputably acknowledged languages spoken in the British Isles belonged to the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family it is not known what language these early farming people spoke. These migrants brought new ideas, leading to a radical transformation of society and landscape that has been called the ]. The Neolithic period in the British Isles was characterised by the adoption of ] and ]. To make room for the new farmland, these early agricultural communities undertook mass ] across the islands, dramatically and permanently transforming the landscape. At the same time, new types of stone tools requiring more skill began to be produced; new technologies included polishing. | |||

| The Neolithic also saw the construction of a wide variety of monuments in the landscape, many of which were ]ic in nature. The earliest of these are the ]s of the Early Neolithic, although in the Late Neolithic this form of monumentalisation was replaced by the construction of ], a trend that would continue into the following ]. These constructions are taken to reflect ideological changes, with new ideas about religion, ritual and social hierarchy. | |||

| ===Bronze Age (2500 to 600 BC)=== | |||

| {{main||Bronze Age Britain|Bronze Age Ireland}} | |||

| {{See also||Bronze Age Europe}} | |||

| In the British Isles, the ] saw the transformation of British and Irish society and landscape. It saw the adoption of agriculture, as communities gave up their hunter-gatherer modes of existence to begin farming. During the British Bronze Age, large ]ic monuments similar to those from the Late Neolithic continued to be constructed or modified, including such sites as ], ], ] and ]. This has been described as a time "when elaborate ceremonial practices emerged among some communities of subsistence agriculturalists of western Europe".<ref>]. p. 05.</ref> | |||

| ===Iron Age (1200 BC to 600 AD)=== | |||

| {{main|British Iron Age|Irish Iron Age}} | |||

| As its name suggests, the British Iron Age is also characterised by the adoption of ], a metal which was used to produce a variety of different tools, ornaments and weapons. | |||

| In the course of the first millennium BC, and possibly earlier, some combination of ] and immigration from continental Europe resulted in the establishment of ] in the islands, eventually giving rise to the ] group. What languages were spoken in the islands before is unknown, though they are assumed to have been ].<ref>{{Harvp|Schama|2000}}.</ref> | |||

| ==Classical period== | |||

| {{main|Roman Britain|Wales in the Roman era|Scotland during the Roman Empire}} | |||

| ], 383–410]] | |||

| In 55 and 54 BC, the Roman general ] launched two ] of the British Isles, though neither resulted in a full Roman occupation of the island. In 43 AD, southern Britain became part of the ]. On ]'s accession Roman Britain extended as far north as ] (]). ], the conqueror of ] (modern-day ] and ]), then became ], where he spent most of his governorship campaigning in Wales. Eventually in 60 AD he penned up the last resistance and the last of the ]s in the island of ] (]). Paulinus led his army across the ] and massacred the druids and burnt their sacred groves. At the moment of triumph, news came of the ] in ].<ref>Peter Salway, ''Roman Britain: a very short introduction'' (Oxford UP, 2015).</ref> | |||

| The suppression of the Boudican revolt was followed by a period of expansion of the Roman province, including the subjugation of south Wales. Between 77 and 83 AD the new governor ] led a series of campaigns which enlarged the province significantly, taking in north Wales, northern Britain, and most of ] (Scotland). The ] fought with determination and resilience, but faced a superior, professional army, and it is likely that between 100,000 and 250,000 may have perished in the ] period.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Copeland |first=Tim |title=Life in a Roman Legionary Fortress |date=2014 |publisher=Amberley Publishing Limited |page=14}}</ref> | |||

| ==Medieval period== | |||

| {{main|Medieval England|Medieval Scotland|Medieval Wales|Early medieval Ireland|Late medieval Ireland}} | |||

| ===Early medieval=== | |||

| <!--for the sources of this section, see the article Anglo-Saxon England, of which this is a summary.--> | |||

| The Early medieval period saw a series of ] by the ]-speaking ], beginning in the 5th century. Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were formed and, through wars with British states, gradually came to cover the territory of present-day England. Scotland was divided between the ], ], the ] and the Angles.<ref name="Smyth1989pp43-6">{{Cite book |last=Smyth |first=A. P. |title=Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 |date=1989 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=0-7486-0100-7 |pages=43–46}}</ref> Around 600, seven principal kingdoms had emerged, beginning the so-called period of the ]. During that period, the Anglo-Saxon states were ] (the conversion of the British ones had begun much earlier). | |||

| In the 9th century, ] from ] ] and the Scots and Picts were combined to form the ].<ref name="Yorke2006p54">{{Cite book |last=Yorke |first=B. |title=The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800 |date=2006 |publisher=Pearson Education |isbn=0-582-77292-3 |page=54}}</ref> Only the Kingdom of Wessex under ] survived and even managed to re-conquer and unify England for much of the 10th century, before a new series of Danish raids in the late 10th century and early 11th century culminated in the wholesale subjugation of England to Denmark under ]. Danish rule was overthrown and the local House of Wessex was restored to power under ] for about two decades until his death in 1066. | |||

| ===Late Medieval=== | |||

| ] depicting events leading to the ], which defined much of the subsequent history of the British Isles]] | |||

| In 1066, ] said he was the rightful heir to the English throne, invaded England, and defeated King ] at the ]. Proclaiming himself to be King William I, he strengthened his regime by appointing loyal members of the Norman elite to many positions of authority, building a system of castles across the country and ordering a census of his new kingdom, the ]. The Late Medieval period was characterized by many battles between England and France, coming to a head in the ] from which France emerged victorious. The English monarchs throughout the Late Medieval period belonged to the houses of Plantagenet, Lancaster, and York.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Prestwich |first=Michael |title=Plantagenet England 1225-1360 |date=2007 |series=New Oxford History of England}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Harriss |first=Gerald |title=Shaping the Nation: England 1360-1461 |date=2005 |series=New Oxford History of England}}</ref> | |||

| Under John Balliol, in 1295, Scotland entered into the ] with France. In 1296, England invaded Scotland, but in the following year ] defeated the English army at the ]. However, King ] came north to defeat Wallace himself at the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mitchison |first=R. |title=A History of Scotland |date=2002 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=0-415-27880-5 |edition=3rd |location=London |pages=43–44}}</ref> In 1320, the ], seen as an important document in the development of Scottish national identity, led to the recognition of Scottish independence by major European dynasties.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Brown |first=M. |title=The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371 |date=2004 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=0-7486-1238-6 |page=217}}</ref> In 1328, the ] with England recognised Scottish independence under ].<ref name="Keen2003">{{Cite book |last=Keen |first=M. H. |title=England in the Later Middle Ages: a Political History |date=2003 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=0-415-27293-9 |edition=2nd |location=London |pages=86–88}}</ref> | |||

| ==Early modern period== | |||

| {{main|Early modern Britain|History of Ireland (1536–1691)|History of Ireland (1691–1801)}} | |||

| Major historical events in the early modern period include the ], the ] and ], the ], the Restoration of ], the ], the ], the ] and the formation of the ]. | |||

| ==19th century== | |||

| {{main|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} | |||

| ===1801 to 1837=== | |||

| {{Further|Georgian era|British Regency|Victorian era|British Empire|Georgian society}} | |||

| ====Union of Great Britain and Ireland==== | |||

| The ] was a settler state; the monarch was the incumbent monarch of England and later of Great Britain.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Watson |first=J. Steven |url=https://archive.org/details/reignofgeorgeiii0000wats |title=The Reign of George III, 1760-1815 |date=1960 |series=Oxford History of England|isbn=978-0-19-821713-8 }}</ref> The ] headed the government on behalf of the monarch. He was assisted by the ]. Both were responsible to the government in London rather than to the ]. Before the ], the Irish parliament was also ], and decisions in Irish courts could be overturned on appeal to the British ] in London. | |||

| The Anglo-Irish ruling class gained a degree of independence in the 1780s thanks to ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=O'Brien |first=Gerard |title=The Grattan Mystique |date=1986 |series=Eighteenth-Century Ireland/Iris an dá chultúr |volume=1 |pages=177–194 |publisher=Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society |jstor=30070822}}</ref> During this time the effects of the ] on the primarily Roman Catholic population were reduced, and some property-owning Catholics were granted the franchise in 1794; however, they were still excluded from becoming members of the ]. This brief period of limited independence came to an end following the ], which occurred during the ]. The British government's fear of an independent Ireland siding against them with the French resulted in the decision to unite the two countries. This was brought about by ] and came into effect on 1 January 1801. The Irish had been led to believe by the British that their loss of legislative independence would be compensated for with ], i.e. by the removal of ] in both Great Britain and Ireland. However, King George III was bitterly opposed to any such Emancipation and succeeded in defeating his government's attempts to introduce it.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Geoghegan |first=Patrick M. |title=The Irish Act of Union: a study in high politics, 1798-1801 |date=1999 |publisher=Gill & Macmillan}}</ref> | |||

| ====Napoleonic Wars==== | |||

| {{Further|Napoleonic Wars}} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ] fires on the French flagship at Trafalgar.]] | ] fires on the French flagship at Trafalgar.]] | ||

Revision as of 02:15, 25 February 2024

Coalition]] (1799–1801), William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806) provided strong leadership in London. Britain occupied most of the French and Dutch overseas possessions, the Netherlands having become a satellite state of France in 1796. After a short peace, in May 1803, war was declared again. Napoleon's plans to invade Britain failed, chiefly due to the inferiority of his navy. In 1805 Lord Nelson's fleet decisively defeated the French and Spanish at Trafalgar, ending any hopes Napoleon had to wrest control of the oceans away from the British.

The British Army remained a minimal threat to France; it maintained a standing strength of just 220,000 men at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, whereas France's armies exceeded a million men—in addition to the armies of numerous allies and several hundred thousand national guardsmen that Napoleon could draft into the French armies when they were needed. Although the Royal Navy effectively disrupted France's extra-continental trade—both by seizing and threatening French shipping and by seizing French colonial possessions—it could do nothing about France's trade with the major continental economies and posed little threat to French territory in Europe. France's population and agricultural capacity far outstripped that of Britain.

In 1806, Napoleon set up the Continental System to end British trade with French-controlled territories. However Britain had great industrial capacity and mastery of the seas. It built up economic strength through trade and the Continental System was largely ineffective. As Napoleon realized that extensive trade was going through Spain and Russia, he invaded those two countries. He tied down his forces in Spain, and lost very badly in Russia in 1812. The Spanish uprising in 1808 at last permitted Britain to gain a foothold on the Continent. The Duke of Wellington and his army of British and Portuguese gradually pushed the French out of Spain, and in early 1814, as Napoleon was being driven back in the east by the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians, Wellington invaded southern France. After Napoleon's surrender and exile to the island of Elba, peace appeared to have returned, but when he escaped back into France in 1815, the British and their allies had to fight him again. The armies of Wellington and Blucher defeated Napoleon once and for all at Waterloo.

Simultaneous with the Napoleonic Wars, trade disputes and British impressment of American sailors led to the War of 1812 with the United States. A central event in American history, it was little noticed in Britain, where all attention was focused on the struggle with France. The British could devote few resources to the conflict until the fall of Napoleon in 1814. American frigates also inflicted a series of embarrassing defeats on the British navy, which was short on manpower due to the conflict in Europe. The Duke of Wellington argued that an outright victory over the U.S. was impossible because the Americans controlled the western Great Lakes and had destroyed the power of Britain's Indian allies. A full-scale British invasion was defeated in upstate New York. Peace was agreed to at the end of 1814, but unaware of this, Andrew Jackson won a great victory over the British at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815 (news took several weeks to cross the Atlantic before the advent of steam ships). The Treaty of Ghent subsequently ended the war with no territorial changes. It was the last war between Britain and the United States.

George IV and William IV

Britain emerged from the Napoleonic Wars a very different country than it had been in 1793. As industrialisation progressed, society changed, becoming more urban and less rural. The postwar period saw an economic slump, and poor harvests and inflation caused widespread social unrest. Europe after 1815 was on guard against a return of Jacobinism, and even liberal Britain saw the passage of the Six Acts in 1819, which proscribed radical activities. By the end of the 1820s, along with a general economic recovery, many of these repressive laws were repealed and in 1828 new legislation guaranteed the civil rights of religious dissenters.

A weak ruler as regent (1811–1820) and king (1820–1830), George IV let his ministers take full charge of government affairs, playing a far lesser role than his father, George III. His governments, with little help from the king, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. His brother William IV ruled (1830–37), but was little involved in politics. His reign saw several reforms: the poor law was updated, child labour was restricted, slavery was abolished in nearly all the British Empire, and, most important, the Reform Act 1832 refashioned the British electoral system.

There were no major wars until the Crimean War (1853–1856). While Prussia, Austria, and Russia, as absolute monarchies, tried to suppress liberalism wherever it might occur, the British came to terms with new ideas. Britain intervened in Portugal in 1826 to defend a constitutional government there and recognising the independence of Spain's American colonies in 1824. British merchants and financiers, and later railway builders, played major roles in the economies of most Latin American nations.

Whig reforms of the 1830s

The Whig Party recovered its strength and unity by supporting moral reforms, especially the reform of the electoral system, the abolition of slavery and emancipation of the Catholics. Catholic emancipation was secured in the Catholic Relief Act of 1829, which removed the most substantial restrictions on Roman Catholics in Great Britain and Ireland.

The Whigs became champions of Parliamentary reform. They made Lord Grey prime minister 1830–1834, and the Reform Act of 1832 became their signature measure. It broadened the franchise and ended the system of "rotten borough" and "pocket boroughs" (where elections were controlled by powerful families), and instead redistributed power on the basis of population. It added 217,000 voters to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. The main effect of the act was to weaken the power of the landed gentry, and enlarge the power of the professional and business middle-class, which now for the first time had a significant voice in Parliament. However, the great majority of manual workers, clerks, and farmers did not have enough property to qualify to vote. The aristocracy continued to dominate the government, the Army and Royal Navy, and high society. After parliamentary investigations demonstrated the horrors of child labour, limited reforms were passed in 1833.

Chartism emerged after the 1832 Reform Bill failed to give the vote to the working class. Activists denounced the "betrayal" of the working classes and the "sacrificing" of their "interests" by the "misconduct" of the government. In 1838, Chartists issued the People's Charter demanding manhood suffrage, equal sized election districts, voting by ballots, payment of Members of Parliament (so that poor men could serve), annual Parliaments, and abolition of property requirements. The ruling class saw the movement as dangerous, so the Chartists were unable to force serious constitutional debate. Historians see Chartism as both a continuation of the 18th century fight against corruption and as a new stage in demands for democracy in an industrial society. In 1832 Parliament abolished slavery in the Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. The government purchased the slaves for £20,000,000 (the money went to rich plantation owners who mostly lived in England), and freed the slaves, especially those in the Caribbean sugar islands.

Leadership

Prime Ministers of the period included: William Pitt the Younger, Lord Grenville, Duke of Portland, Spencer Perceval, Lord Liverpool, George Canning, Lord Goderich, Duke of Wellington, Lord Grey, Lord Melbourne, and Sir Robert Peel.

Victorian era

Main article: Victorian era

The Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's rule between 1837 and 1901 which signified the height of the British Industrial Revolution and the apex of the British Empire. Scholars debate whether the Victorian period—as defined by a variety of sensibilities and political concerns that have come to be associated with the Victorians—actually begins with the passage of the Reform Act 1832. The era was preceded by the Regency era and succeeded by the Edwardian period. Victoria became queen in 1837 at age 18. Her long reign saw Britain reach the zenith of its economic and political power, with the introduction of steam ships, railroads, photography, and the telegraph. Britain again remained mostly inactive in Continental politics.

Free trade imperialism

The Great London Exhibitio m cxkmc njklcndoidmom n of 1851 clearly demonstrated Britain's dominance in engineering and industry; that lasted until the rise of the United States and Germany in the 1890s. Using the imperial tools of free trade and financial investment, it exerted major influence on many countries outside Europe, especially in Latin America and Asia. Thus Britain had both a formal Empire based on British rule as well as an informal one based on the British pound.

Russia, France and the Ottoman Empire

One nagging fear was the possible collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It was well understood that a collapse of that country would set off a scramble for its territory and possibly plunge Britain into war. To head that off Britain sought to keep the Russians from occupying Constantinople and taking over the Bosporous Strait, as well as from threatening India via Afghanistan. In 1853, Britain and France intervened in the Crimean War against Russia. Despite mediocre generalship, they managed to capture the Russian port of Sevastopol, compelling Tsar Nicholas I to ask for peace. It was a frustrating war with very high casualty rates—the iconic hero was Florence Nightingale.

The next Russo-Ottoman war in 1877 led to another European intervention, although this time at the negotiating table. The Congress of Berlin blocked Russia from imposing the harsh Treaty of San Stefano on the Ottoman Empire. Despite its alliance with the French in the Crimean War, Britain viewed the Second Empire of Napoleon III with some distrust, especially as the emperor constructed ironclad warships and began returning France to a more active foreign policy.

American Civil War

During ITV News |language=en |archive-date=2022-07-07 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220707190455/https://www.itv.com/news/2022-07-06/timeline-of-how-each-crisis-unfolded-under-boris-johnson |url-status=live }}</ref> He was replaced as Prime Minister by Foreign Secretary Liz Truss 5 September, three days before the accession of King Charles III on the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

Periods

- Prehistoric Britain (Prehistory–AD 43)

- Roman Britain (44–407)

- Sub-Roman Britain (407–597)

- Britain in the Middle Ages (597–1485)

- Anglo-Saxon England (597–1066)

- Scotland in the Early Middle Ages (400–900)

- Scotland in the High Middle Ages (900–1286)

- Norman Conquest (1066)

- Scotland in the Late Middle Ages (1286–1513)

- Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–1357)

- Wales in the Middle Ages (411-1542)

- Early modern Britain

- Tudor period (1485–1603)

- First British Empire (1583–1783)

- Jacobean era (1567–1625)

- Union of the Crowns (1603)

- Caroline era (1625–1642)

- English Civil War (1642–1651)

- English Interregnum (1651–1660)

- Restoration (1660)

- Glorious Revolution (1688)

- Scottish Enlightenment

- Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1800)

- Second British Empire (1783–1815)

- Georgian era

- History of the United Kingdom (1801–)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922)

- Britain's Imperial Century (1815–1914)

- Regency (1811–1820)

- Victorian era (1837–1901)

- Edwardian period (1901–1910)

- Britain in World War I (1914–1918)

- Coalition Government 1916–1922

- Irish War of Independence (1919-1921)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1922–)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922)

Timeline history of the British Isles

Geographic

- History of England (Timeline)

- History of Scotland

- History of Wales

- History of Ireland

- History of the Isle of Man

- History of Jersey

States

- England in the Middle Ages

- Kingdom of England (to 1707)

- Kingdom of Scotland (to 1707)

- Kingdom of Ireland (1541–1801)

- Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1927)

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1927 – )

- Isle of Man (unrecorded date to present)

Supranational

See also

- Timeline of the British Army

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- British military history

- List of British monarchs

- Economic history of the United Kingdom

- History of British society

- Outline of the History of the British Isles

References

- Wilson, P. W. (1930). William Pitt The Younger.

- Knight, Roger (2014). Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793-1815.

- Adkins, Roy (2006). Nelson's Trafalgar: The Battle That Changed the World.

- Bell, David A. (2007). The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It.

- Thompson, J. M. (1951). Napoleon Bonaparte: His rise and fall. pp. 235–240.

- Foster, R.E. (2014). Wellington and Waterloo: The Duke, the Battle and Posterity 1815-2015.

- Black, Jeremy (2009). The War of 1812 in the Age of Napoleon.

- Woodward (1938).

- Hilton, Boyd (2008). A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People?: England 1783-1846. New Oxford History of England.

- Baker, Kenneth (2005). "George IV: a Sketch". History Today. 55 (10): 30–36.

- Brock, Michael (2004). "William IV (1765–1837". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29451. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Black, Jeremy (2008). A military history of Britain: from 1775 to the present. pp. 74–77.

- Kaufmann, William W. (1967). British policy and the independence of Latin America, 1804–1828.

- Kaufman, Will; Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl, eds. (2004). Britain and the Americas: culture, politics, and history. pp. 465–468.

- ^ Woodward (1938), pp. 325–330

- Chase, Malcolm (2007). Chartism: A New History.

- Woodward (1938), pp. 354–357.

- McCord, Norman; Purdue, Bill (2007). British History, 1815-1914 (2nd ed.).

- Semmel, Bernard (1970). "Chapter 1". The Rise of Free Trade Imperialism. Cambridge University Press.

- McLean, David (1976). "Finance and "Informal Empire" before the First World War". Economic History Review. 29 (2): 291–305. doi:10.2307/2594316. JSTOR 2594316.

- Golicz, Roman (2003). "The Russians Shall Not Have Constantinople". History Today. 53 (9): 39–45.

- Figes, Orlando (2012). The Crimean War: A History.

- McDonald, Lynn (2010). "Florence Nightingale a hundred years on: Who she was and what she was not". Women's History Review. 19 (5): 721–740. doi:10.1080/09612025.2010.509934. PMID 21344737. S2CID 9229671.

- Millman, Richard (1979). Britain and the Eastern Question 1875–1878.

- Chamberlain, Muriel E. (1989). Pax Britannica?: British Foreign Policy 1789-1914.

Works cited

- Woodward, E. L. (1938). The Age of Reform, 1815–1870.

Further reading

- Schama, Simon. A History of Britain. BBC.

- —— (2000). At the Edge of the World? 3000 BC – 1603 AD. Vol. 1. ISBN 0-7868-6675-6.

- —— (2001). The Wars of the British 1603-1776. Vol. 2. ISBN 0-563-48718-6.

- —— (2003). The Fate of Empire 1776–2000. Vol. 3. ISBN 0-563-48719-4.

- —— (2002). The Complete Collection (video).

- The British Isles: A History of Four Nations by Hugh Kearney, Cambridge University Press 2nd edition 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-84600-4

- The Isles, A History by Norman Davies, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-19-513442-7

- Shortened History of England by G. M. Trevelyan Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-023323-7

- This Sceptred Isle: 55BC-1901 by Christopher Lee Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-026133-8 (originally a radio series )

- The Reduced History of Britain by Chas Newkey-Burden

- The Great Heritage: a History of Britain for Canadians by Richard S. Lambert, House of Grant, 1964 (and earlier editions and/or printings)

External links

- British History

- World History Database

- The most comprehensive sites on British History

- Encyclopedia of British History

- 1000 years of British history

- British History Online

- Homepage of the BBC History website

- British History Interactive Timeline

- Rutgers University Libraries - American and British History

- British History at about.com

- English History and Heritage guide - History of England

- The British History Site with rss feed#

- Mytimemachine.co.uk

- The British History Podcast

- The History Files

| History of the British Isles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overview |  | |

| Prehistoric period | ||

| Classical period | ||

| Medieval period | ||

| Early modern period | ||

| Late modern period | ||

| Related | ||

| British Isles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||||||

| History (outline) |

| ||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||